17 The hip region

Disorders of the hip are common both in children and in adults. Prominent among childhood affections are developmental (congenital) dislocation of the hip and Perthes’ disease (osteochondritis) of the head of the femur. The hip is subject to all types of arthritis, but in adults osteoarthritis is overwhelmingly the most prominent affection.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF HIP COMPLAINTS

History

Age incidence of hip disorders. Many of the important disorders of the hip occur in childhood, and often at a particular period of childhood. So true is this with some disorders that the age of the patient at the onset of symptoms affords some indication of the likely nature of the trouble, as shown in Table 17.1. (For ease of memorising, round figures have been given in the table but some latitude must be allowed.)

Table 17.1 Usual age incidence of common hip disorders at time of diagnosis

| Age at time of diagnosis (years) | Disease |

|---|---|

| 0–2 | Developmental (congenital) dislocation |

| 2–5 | Tuberculous arthritis; transient synovitis |

| 5–10 | Perthes’ disease; transient synovitis |

| 10–20 | Slipped upper femoral epiphysis |

| 20–50 | Osteoarthritis (secondary to previous injury or disease) |

| 50–100 | Osteoarthritis (primary) |

Exposure

For the proper examination of the hip the patient should be stripped except for a pelvic slip or underpants and, in women, a bra. The first part of the examination is conducted with the patient lying supine; afterwards the patient is examined standing and walking.

Steps in clinical examination

A suggested routine for clinical examination of the hip is summarised in Table 17.2.

Table 17.2 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the hip

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE HIP REGION | |

| (Patient supine) | Examination for fixed deformity |

| Position of pelvis | Including Thomas’s manoeuvre for detection and measurement of fixed flexion deformity |

| Determine the lie of the pelvis and set it square with the limbs if possible | |

| Movements (active and passive) | |

| Inspection | Flexion |

| Bone contours and alignment | Abduction; abduction in flexion |

| Soft-tissue contours | Adduction |

| Colour and texture of skin | Medial (internal) rotation |

| Scars or sinuses | Lateral (external) rotation |

| Palpation | Power (tested against resistance of examiner) |

| Skin temperature | Estimate strength of each muscle group: |

| Bone contours | flexors, extensors, abductors, adductors, rotators |

| Soft-tissue contours | |

| Local tenderness | |

| Examination for abnormal mobility | |

| Measurement of limb length | Test for longitudinal (telescopic) movement |

| Real or true length: | Click test (in new-born) |

| Measure from anterior superior iliac spine to medial malleolus | (patient standing) |

| Examination for postural stability | |

| (angle between pelvis and limbs to be equal on each side) | Trendelenburg’s test |

Setting the pelvis square

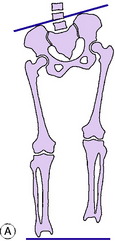

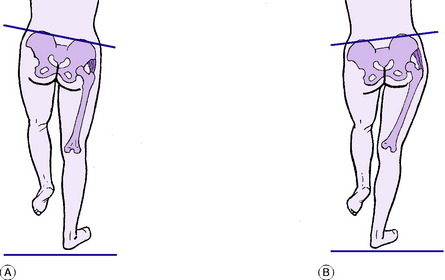

This is an important preliminary step. Determine from the position of the anterior superior iliac spines whether or not the pelvis is lying square with the limbs (Fig. 17.1). If it is not, an attempt is made to set it square. If this is impossible it means that there is incorrectable adduction or abduction at one or other hip (or, rarely, a severe and rigid curvature of the spine): in that event the fact that the pelvis is tilted should be noted and borne in mind during the subsequent steps of the examination.

Measuring the length of the limbs

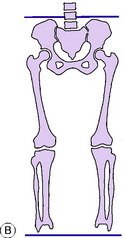

It is necessary to measure, first, the real or true length of each limb. Secondly, it is necessary to determine whether there is any ‘apparent’ or false discrepancy in the length of the limbs from fixed pelvic tilt (Fig. 17.2). Whereas it is always necessary to measure the true length, it is necessary to measure ‘apparent’ discrepancy only when there is an incorrectable tilt of the pelvis.

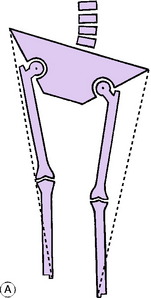

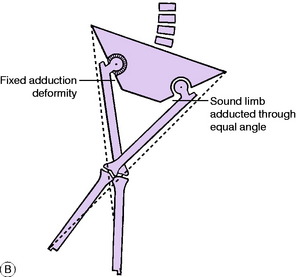

It should be noted that the anterior superior spine is well lateral to the axis of hip movement. This is of no consequence if the angle between limb and pelvis is the same on each side. But it will render the measurements fallacious if the angle between limb and pelvis is not the same on each side. This will be understood best by reference to Fig. 17.3A. It will be seen that abduction of a limb brings the medial malleolus nearer to the corresponding anterior superior spine, whereas adduction of the limb carries the medial malleolus away from the anterior superior spine. Thus if measurements are made while the patient lies with one hip adducted and the other abducted (a common posture in cases of hip disease) inaccurate readings will be obtained: the length will be exaggerated on the adducted side and underestimated on the abducted side.

The rule is, therefore, that to obtain an accurate comparison of their true length by surface measurement the two limbs must be placed in comparable positions relative to the pelvis. Thus if one limb is adducted and cannot be brought out to the neutral position, the other limb must be adducted through a corresponding angle by crossing it over the first limb before the measurements are taken (Fig. 17.3B). Similarly, if one hip is in fixed abduction the other must be abducted through the same angle before the measurements of true length are made.

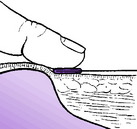

Fixing the tape measure at the anterior superior spine. A flat metal end (as found on the ordinary tailor’s measure) is essential. The metal end is placed immediately distal to the anterior superior spine and is pushed up against it. The thumb is then pressed firmly backwards against the bone and the tape end together (Fig. 17.4). This gives rigid fixation of the tape measure against the bone and minimises any error in measurement.

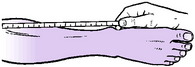

Taking the reading at the medial malleolus. The tip of the index finger is placed immediately distal to the medial malleolus and pushed up against it. The thumb nail is brought down against the tip of the index finger so that the tape measure is pinched between them (Fig. 17.5). The point of measurement is indicated by the thumb nail.

Determining the site of true shortening. If measurements reveal real shortening of a limb it is necessary to determine whether the shortening is above the trochanteric level (suggesting an affection in or near the hip), or below the trochanteric level (suggesting a disorder of the limb bones).

Shortening above the greater trochanter. Tests for shortening above the trochanteric level are: the measurement of Bryant’s triangle, Nelaton’s line, or Schoemaker’s line.

Measurement of ‘apparent’ discrepancy in limb length. ‘Apparent’ or false discrepancy in limb length is due entirely to incorrectable sideways tilting of the pelvis (Fig. 17.2A). The usual cause is a fixed adduction deformity at one hip, giving an appearance of shortening on that side, or a fixed abduction deformity, giving an appearance of lengthening. Exceptionally, fixed pelvic obliquity is caused by severe lumbar scoliosis.

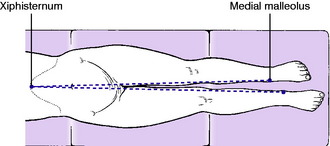

To measure apparent discrepancy the limbs must be placed parallel to one another and in line with the trunk. Measurement is made from any fixed point in the midline of the trunk (for example, the xiphisternum) to each medial malleolus (Fig. 17.6).

Examination for fixed deformity

Fixed adduction deformity. This is detected by judging the relationship between pelvis and limbs. It will already have been noted at an earlier stage of the examination. If fixed adduction is present the transverse axis of the pelvis (as indicated by a line joining the two anterior superior spines) cannot be set at right angles to the affected limb, but lies at an acute angle with it.

Fixed flexion deformity. This is determined by a manoeuvre known as Thomas’s test.

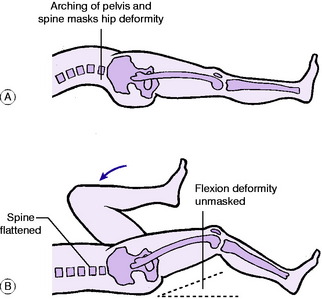

Principle of Thomas’s test. If there is a fixed flexion deformity at the hip the patient compensates for it, when lying on the back, by arching the spine and pelvis into exaggerated lordosis, as shown in Fig. 17.7A. This allows the affected limb to lie flat on the couch. To measure the angle of fixed flexion deformity it is necessary to correct the lumbo-pelvic lordosis. This is done by flexing the pelvis (and with it the lumbar spine) by means of the fully flexed sound limb (Fig. 17.7B).

Technique of the manoeuvre. One hand is placed behind the lumbar spine (between it and the couch) to assess the degree of lumbar lordosis. If there is no lordosis when the affected limb lies flat on the couch there can be no fixed flexion deformity and there is no need to proceed with the test. If there is excessive lordosis, as indicated by arching of the back (Fig. 17.7A), it is corrected in the following way: The sound hip is flexed to the limit of its range. The limb is then pushed further into flexion, thereby rotating the pelvis on a horizontal transverse axis until the arching of the spine is obliterated. During this manoeuvre the thigh of the disordered limb, if in fixed flexion, is automatically raised from the couch as the lumbar lordosis is reduced (Fig. 17.7B). The angle through which the thigh is raised from the couch is the angle of fixed flexion deformity.

Fixed rotation deformity. The most reliable index of the rotational position of the thigh is the patella, which normally points forwards when the hip is in the neutral position. If there is fixed lateral rotation or fixed medial rotation the limb cannot be rotated to the neutral position, with the patella directed forwards. The angle by which it falls short of the neutral when rotated as far as possible is the angle of fixed rotation deformity.

Movements

Flexion. The range of hip flexion is best demonstrated by flexing the hip and knee together; not by lifting the leg with the knee straight. Movement of the pelvis is best detected by grasping the crest of the ilium (Fig. 17.8). Only in this way is it possible to distinguish between true hip movement and the false flexion imparted by rotation of the pelvis. The normal range of true hip flexion is about 130 °, but it varies according to the build of the patient.

Abduction. The limb to be tested is supported by one hand while the other hand bridges the pelvis from anterior superior spine to anterior superior spine (Fig. 17.9). In this way true abduction at the hip can be differentiated from the false abduction that is imparted by tilting of the pelvis. The normal range of true abduction at the hip is 30 ° to 35 ° (more in children).

Abduction in flexion. This is often the first movement to suffer restriction in arthritis of the hip. The patient flexes his hips and knees by drawing the heels towards the buttocks. He then allows the knees to fall away from one another towards the couch (see Fig. 17.11B). The normal range is about 70 ° (90 ° in young children).

Examination for abnormal mobility

In infants it is important to examine for dislocation by the click tests of Ortolani and Barlow. These are described on page 344.

Examination for postural stability: the Trendelenburg test

Principle of the test. Normally, when one leg is raised from the ground the pelvis tilts upwards on that side, through the action of the hip abductors of the standing limb (Fig. 17.10A). (This automatic mechanism allows the lifted leg to clear the ground in walking.) If the abductors are inefficient they are unable to sustain the pelvis against the body weight and it tilts downwards instead of rising up on the side of the lifted leg (Fig. 17.10B).

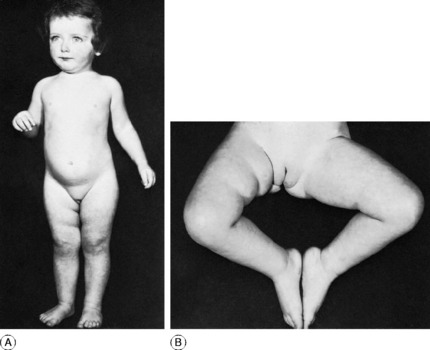

Fig. 17.11 Congenital dislocation of the right hip. A The right lower limb was slightly shorter than the left, as suggested here by the typical extra skin folds in the thigh. B shows the reduced range of abduction of the affected hip – another typical and important diagnostic feature.

Technique. Stand behind the patient. Instruct him first to stand upon the sound limb and to raise the other from the ground. Having thus got the idea of what he is required to do, he should now stand on the affected leg and lift the sound leg from the ground. By inspection, or by palpation with a hand upon the iliac crest, observe whether the pelvis rises or falls on the lifted side. Remember that the limb upon which the patient stands is the one under test. If the pelvis rises on the opposite side (normal) the test is negative (Fig. 17.10A). If it falls, the test is positive (Fig. 17.10B); in other words the abductor muscles are incapable of stabilising the pelvis upon the femur.

Causes of positive Trendelenburg test. There are three fundamental causes:

Gait

The patient’s ability to negotiate stairs must also be tested. A disability of the hip often precludes the normal rhythm of ascent and descent: on ascending, the foot of the sound leg is advanced first, and that of the affected side is then brought up to it. On descent, the affected leg is put down first and the sound leg is brought down to it.

Imaging

Computerised tomography (CT scanning) provides clear cross-sectional images of the pelvis or thigh and is useful in special circumstances. For instance, it can show accurately the orientation (degree of anteversion) of the acetabulum or of the neck of the femur. Or it may be used to outline bony or soft-tissue tumours in or about the pelvis or hip (see Fig. 2.3, p. 15).

DEVELOPMENTAL DYSPLASIA OF THE HIP

The term developmental dysplasia of the hip includes congenital dislocation of the hip, nearly always diagnosed either within a few days of birth or within the first two years of life; and dysplasia of the hip in adults, characterised by shallow configuration of the acetabulum, defective congruity between the femoral head and the socket, and a predisposition to osteoarthritis in middle or later life. Despite a trend towards re-naming congenital dislocation of the hip as developmental dysplasia of the hip, the title ‘congenital dislocation’ of the hip is so well established that it seems unnecessary to discard it. That title is therefore retained here for dislocation diagnosed in infancy.

CONGENITAL DISLOCATION OF THE HIP

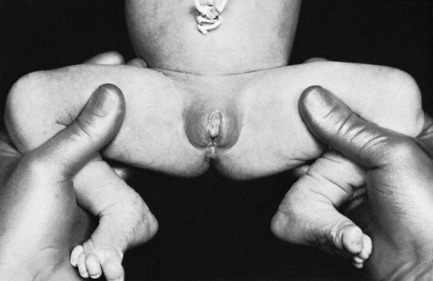

On examination at that time, the main features in unilateral cases are asymmetry (notably of the buttock folds), shortening of the affected limb (Fig. 17.11A), and restricted abduction in flexion. In bilateral cases the striking features are widening of the perineum and marked lumbar lordosis. The range of joint movements is full except for abduction in flexion, which is characteristically slightly restricted (Fig. 17.11B). In most cases the affected limb is abnormally mobile in its long axis (telescopic movement).

Imaging. Plain radiographs show three important features (Fig. 17.12):

These changes are not always shown conclusively before the age of 4 months.

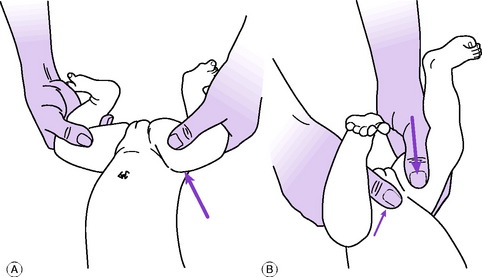

Diagnosis. In the new-born. Nearly always – though there are a few exceptions—dislocation or instability of the hip may be detected in the first few days of life by the diagnostic screening tests of Barlow or Ortolani (Fig. 17.13). In both tests the surgeon faces the child’s perineum and grasps the upper part of each thigh between fingers behind and thumb in front, the child’s knees being fully flexed and the hips flexed to a right angle (Fig. 17.14). While each thigh in turn is steadily abducted towards the couch the middle finger applies forward pressure behind the greater trochanter (Ortolani), and alternately the thumb, placed anteriorly, applies backward pressure while the thighs are adducted (Barlow). One of two abnormal states may be detected:

The manoeuvre must be combined with assessment of the range of abduction in flexion at each hip (Fig. 17.11B). If abduction is restricted it may indicate persistent or irreducible dislocation, and in such a case the absence of the characteristic jerk or jolt may mislead the observer into believing that all is well. In such a case, if unilateral, shortening may be observed when the knees are placed together, with the hips flexed.

In older children. Delay in beginning to walk or abnormality of gait in early childhood should always arouse suspicion. The most important clinical sign in children 1 or 2 years old is a restricted range of abduction when the hip is flexed (Fig. 17.11B). If for any reason suspicion arises that all is not well with the hips, radiographic examination must be insisted upon. In these older children radiography is always conclusive.

Course and prognosis. The earlier the dislocation is reduced the better the prognosis. Even under the best conditions only about half or two-thirds of the patients treated after the first year of life can be expected to remain permanently free from trouble. Gradual redislocation or subluxation is all too frequent, and pain from secondary degenerative changes often develops in middle adult life.

Treatment

If at 3 weeks the hip is found to be stable, treatment is unnecessary, and the parents may be tentatively reassured. Nevertheless it is important that the child should be reviewed at the age of 5 or 6 months, when radiography gives conclusive findings, and again at 1 year of age.

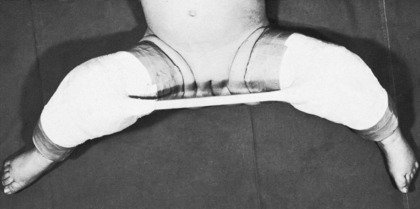

If on the other hand the hip is still unstable at 3 weeks, splinting in the reduced position in moderate (not extreme) abduction for 3 months is recommended. Splintage may be by plaster of Paris or more frequently using the Pavlic harness (Fig. 17.15), which is more flexible than the previously used Denis-Browne or Van Rosen splints. The dynamic Pavlic splint has an adjustable harness that can maintain the hips in flexion while limiting adduction. Splintage should be continued for a minimum of 6 weeks or for as long as instability persists, though this carries an increasing risk of the development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

Reduction of dislocation. It is desirable whenever possible to obtain reduction by non-operative means, operation being used only when conservative methods fail. In practice, it is found that closed reduction is often possible in babies up to 18 months of age, but that thereafter the proportion that require operation progressively increases, so that operative reduction becomes almost routine after the age of 3 years.

If full reduction is secured, the limbs are immobilised for an initial period in plaster of Paris, usually in a position of moderate medial rotation and moderate abduction (Fig. 17.16): extreme positions must not be used. This has superseded the ‘frog’ position of right-angled flexion and abduction, formerly widely used, which has been found to prejudice the blood supply of the capital epiphysis of the femur, with risk of necrotic changes resembling those of Perthes’ disease.

Operative reduction. If reduction is not obtained by traction and abduction, with or without manipulation, or when a soft-tissue obstruction to reduction has been demonstrated by arthrography, operation should be undertaken without delay. At operation, it will usually be found that full engagement of the femoral head in the acetabulum is prevented by inturning of the acetabular labrum (limbus), or occasionally by a voluminous ligament of the femoral head or a tight psoas tendon. Any such obstruction is removed or released to allow the femoral head to be fully engaged. While the femoral head is exposed to view, note should be made of the angle of anteversion of the femoral neck. This will often be found to be increased beyond the normal angle of 25 °. At the completion of the operation the limbs are immobilised in plaster in the same way as after closed reduction.

There are two methods of correcting excessive anteversion:

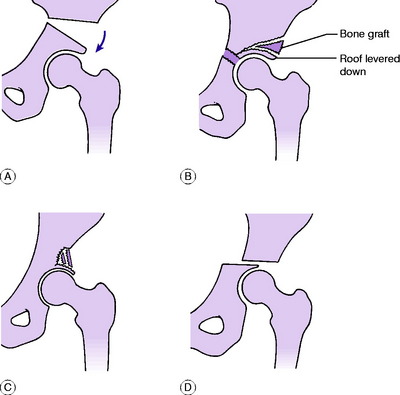

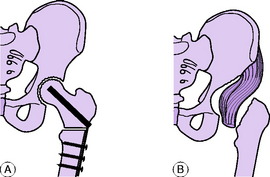

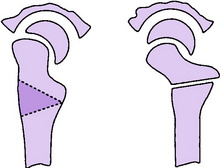

Osteotomy of the innominate bone (Salter). The iliac bone is divided completely just above the acetabulum, the cut emerging at the greater sciatic notch. The whole of the lower half of the bone, bearing the intact acetabulum, is then sprung outwards and forwards, hinging at the symphysis pubis (Fig. 17.17A). The effect is that the femoral head is more fully covered by the roof of the acetabulum, and stability of the hip is correspondingly increased. This operation is most suitable for young children in whom the acetabular socket and femoral head are congruent.

Pericapsular osteotomy of ilium (Pemberton). This operation has a similar aim of providing increased cover for the femoral head by the roof of the acetabulum. A curved osteotomy is made part-way across the thickness of the pelvic wall from the outer aspect of the ilium a few millimetres proximal to the attachment of the capsule to the upper margin of the acetabulum. The osteotomy extends to the triradiate cartilage, which forms a flexible hinge about which the roof of the acetabulum is deflected downwards over the femoral head. The triangular osteotomy gap is held open by bone obtained locally from the ilium (Fig. 17.17B). This operation is most suitable for young children in whom the acetabular socket is relatively shallow compared to the shape of the femoral head.

Cortical turn-down acetabuloplasty (Wainwright). This so-called shelf operation also has the aim of increasing the surface area of the acetabular roof. A sizeable area of the outer table of the ilium is turned down as a flap into contact with the upper and outer aspect of the capsule of the hip joint (Fig. 17.17C). The flap, thus reflected, is held in place by strut grafts. This operation is suitable mainly for adolescents and young adults.

Chiari’s pelvic displacement osteotomy. The iliac bone is divided almost transversely immediately above the acetabulum, and the lower fragment (bearing the acetabulum) is displaced medially (Fig. 17.17D). The cut surface of the upper fragment thus forms an extension of the acetabular roof, with capsule and newly formed fibrous tissue intervening. The operation is suitable mainly for adolescents and young adults.

Age 11 years onwards. After the age of 10 years, and often in younger children, treatment of freshly diagnosed congenital dislocation of the hip is not advised unless secondary degenerative changes lead to severe pain. If increasing pain justifies operative treatment, the choice of method depends largely upon whether the dislocation affects one or both hips. If only one hip is affected total replacement arthroplasty may sometimes be practicable once adult life is reached; but if not, consideration should be given to the advisability of arthrodesis, which can offer a satisfactory solution. If both hips are affected (Fig. 17.18), if it is practicable, replacement arthroplasty is usually to be preferred.

DYSPLASIA OF THE HIP IN ADULTS

Hip dysplasia in adults may become symptomatic at any time from early adult life up till middle age, or later. The common presenting symptom is pain, usually in one hip, but often occurring later, or in lesser degree, in the opposite hip as well. Examination shows good mobility of the hip, but often with complaint of pain at the extremes of the range, especially of flexion and abduction. On radiological examination the affected acetabulum is seen to be shallow, often with a steeply sloping roof (Fig. 17.19). The femoral head does not fit concentrically in the acetabulum: it may be shown to be displaced slightly upwards and outwards, so that Shenton’s line – the normally smooth arch formed by the medial/inferior border of the femoral neck prolonged into the inferior border of the pubic ramus – is broken.

Treatment. Operative treatment is often appropriate, but it should be deferred until the disability becomes severe enough to demand it. The choice of operation is usually between osteotomy of the upper end of the femur to displace the femoral head and neck into more varus (Fig. 17.20), and pelvic osteotomy above the acetabulum to increase the coverage of the femoral head and improve stability of the hip (Fig. 17.17D). In patients with established arthritic changes total replacement arthroplasty of the hip may have to be recommended, even in patients who are relatively young.

TRANSIENT SYNOVITIS OF THE HIP (Traumatic synovitis; transient arthritis; observation hip; irritable hip)

Cause. This is unknown. Injury is possibly a factor but the evidence in support of it is slender.

Diagnosis. Transient arthritis of the hip is important only because it resembles clinically the earliest stages of pyogenic arthritis, tuberculous arthritis or of Perthes’ disease, before the characteristic radiographic features of those conditions have become apparent. Transient arthritis should be diagnosed only after the hip has recovered – never while the symptoms and signs are present. While the symptoms and signs last, the case should be regarded as one of suspected infective arthritis or Perthes’ disease and the child investigated fully to exclude these diagnoses. Ultrasound scanning may be indicated to identify any joint effusion which would require aspiration. Full recovery within a few weeks excludes more serious disease and justifies a retrospective diagnosis of transient synovitis.

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE HIP (General description of pyogenic arthritis, p. 96)

In infants bony ankylosis does not occur because the femoral head and the acetabulum are composed almost entirely of cartilage rather than of bone, but there may be total destruction of the developing femoral head, with secondary dislocation of the hip (pathological dislocation) (Tom Smith’s disease1). The femur may remain short, from destruction of the upper femoral growth cartilage. Additional shortening will occur if the dislocation is allowed to persist and the femur to slide upwards on the ilium; so the discrepancy in length may be substantial by the time adolescence is reached.

On examination it is not always apparent at first that the hip is the seat of the trouble. But careful examination will show thickening in the hip area, and movements of the joint are restricted, and disturb the child. Sometimes an abscess points at the skin surface in the buttock or thigh.

Imaging. In the early stages there is no alteration in the plain radiographs, but ultrasound scanning may show the hip joint to be distended with fluid (Fig. 7.13, p. 99). If the infection progresses to the stage of destroying the capital epiphysis of the femur, the ossific nucleus fails to appear as it should before the age of one year. In such a case subsequent radiographs may show gradual dislocation of the hip. This ‘pathological’ dislocation is distinguished from congenital dislocation by the facts that the acetabular roof is of normal shape and that the capital epiphysis is permanently absent (Fig. 17.21). Radioisotope scanning reveals increased uptake in the region of the hip.

Imaging. There may be no change on plain radiographs in the early stages, but ultrasound will demonstrate the presence of an effusion (Fig. 7.13, p. 99). There may be evidence of osteomyelitis in the upper metaphysis of the femur. Later, if the infection persists, there is rarefaction of bone about the hip, and the cartilage space is narrowed, indicating destruction of articular cartilage. Finally, there may be bony ankylosis of the joint (Fig. 17.22).

Radioisotope bone scanning shows increased uptake in the region of the hip.

Investigations in both the infantile and childhood forms of suspected septic arthritis are similar. There is a polymorphonuclear leucocytosis and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level are raised. Blood cultures are taken and if ultrasound shows a joint effusion, aspiration of the joint is urgent yielding pus or turbid fluid from which the causative organism and its antibiotic sensitivities may be identified.

Pathological dislocation complicating pyogenic arthritis of infants, with total destruction of the upper femoral epiphysis. Definitive treatment of this rare but crippling condition must await adolescence. In childhood the aim of treatment is to prevent progressive upward displacement of the femur and thereby to minimise shortening. Provided the infection has settled, operation should be undertaken to deepen the acetabulum, to place the upper end of the femur within it and, if necessary, to lever down a ‘shelf’ of ilium over it, on the lines of the Pemberton osteotomy illustrated in Figure 17.17B. In adolescence, when the bones are nearing full development, arthrodesis may be recommended if the hip is painful. If the hip has fused spontaneously (Fig. 17.22) the situation is best accepted, provided that fusion has occurred in a good functional position.

TUBERCULOUS ARTHRITIS OF THE HIP (General description of tuberculous arthritis, p. 98)

The hip is one of the joints most frequently affected by tuberculosis. In Western countries, however, its incidence has declined so sharply that it is now seldom seen, and it is mainly confined to poorer countries or to immigrants from such countries.

Imaging. Radiographic features. At first the changes are slight, but later there are fuzziness of the joint margins and narrowing of the cartilage space, indicating erosion of the articular cartilage (Fig. 17.23).

Treatment. Essentially, treatment is the same as that for other tuberculous joints. The mainstay of treatment is a prolonged course of antibacterial agents, as described on page 102.

On the other hand, if at the end of 3 or 6 months’ treatment radiographs show marked destruction of cartilage or bone (Fig. 17.23), there is no possibility of preserving the joint intact. The choice then lies between total replacement arthroplasty and arthrodesis. Arthroplasty should only be undertaken when the disease is quiescent, and will require the reintroduction of antibacterial drugs to cover the period of operation. In children such operations should be deferred until adolescence.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE HIP (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

The hip joints often escape in cases of rheumatoid arthritis; but when they are affected the consequent disability is severe. The main features of the disease are like those of rheumatoid arthritis in general, as described on page 134.

Imaging. Radiographic features. In the earliest stages there are no radiographic changes. Later, there is diffuse bone rarefaction in the area of the joint. Later still, destruction of articular cartilage leads to narrowing of the cartilage space between femur and acetabulum, often with inward protrusion of the softened medial wall of the acetabulum (Fig. 17.24).

Course. The disease becomes inactive after months or years, but the hip is seldom restored to normal. In long-established cases degenerative changes are superimposed upon the original inflammatory condition, giving rise to secondary osteoarthritis (Fig. 17.24A).

Treatment. Medical treatment is the same as that for rheumatoid arthritis in general (p. 137). Local treatment for the hip joints depends upon the activity and severity of the inflammatory reaction. When the reaction is moderate or mild, exercises under physiotherapy supervision and active use within the limits of pain are encouraged. Intra-articular injections of hydrocortisone have sometimes given relief, but they cannot safely be repeated.

Operative treatment is justified when pain is severe and walking is limited to a few yards. Replacement arthroplasty (see Fig. 17.27A, p. 363) is the method of choice and can be expected to give as good results as in patients with osteoarthritis, though involvement of other joints in the lower limb may continue to impair mobility.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE HIP (General description of osteoarthritis, p. 140)

Osteoarthritis of the hip is a common cause of severe disablement, especially in the elderly. It is not uncommon even in younger patients, when it is usually secondary to previous injury or disease. Indeed operations for the relief of osteoarthritis of the hip now make up a substantial part of the work of an orthopaedic department.

Clinical features. The patient is usually elderly; but when osteoarthritis is secondary to previous hip disease or to injury it often arises in middle life or even earlier. There is pain in the groin and front of the thigh; often also in the knee. The pain is made worse by walking and eased by rest. Later, there may be complaint of stiffness, which manifests itself in everyday life by inability to reach the foot to tie the shoe laces or cut the toe nails. The symptoms tend to increase progressively month by month and year by year until they eventually cause severe painful limp and incapacity for normal activities.

On examination all hip movements are impaired. Limitation of abduction, adduction, and rotation is marked, but a good range of flexion is often preserved. Forced movements are painful. Fixed deformity (flexion, adduction, or lateral rotation, or a combination of these) is common (see Fig. 17.26).

Radiographic features. The changes are characteristic. There is diminution of the cartilage space, with a tendency to sclerosis of the subchondral bone and cyst formation (Figs 17.25 and 17.26). Hypertrophic spurring of bone (osteophyte formation) is usually seen at the joint margins.

Fig. 17.26 Advanced osteoarthritis of right hip. Note the adduction deformity – a common feature that causes apparent shortening of the limb from tilting of the pelvis. As in Figure 17.25, the characteristic features are narrowing of the joint space, subchondral bone sclerosis, and marginal osteophytes.

though the last two are now seldom used.

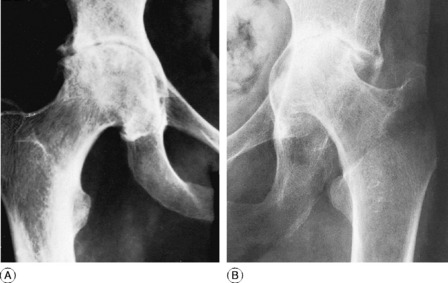

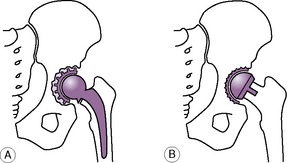

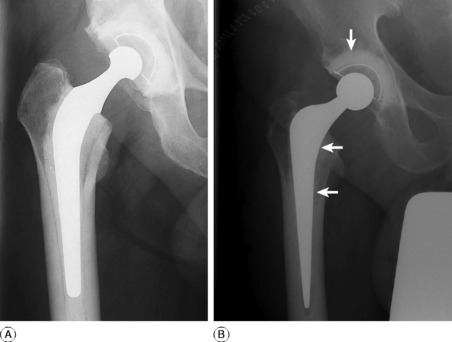

Arthroplasty. The method most commonly used in primary management is total replacement arthroplasty (Figs 17.27A and 17.29A). Excision arthroplasty (Fig. 17.28B) is now only used as a salvage operation after other methods of treatment have failed, particularly when replacement arthroplasty has failed on account of infection.

In total replacement arthroplasty both the femoral and acetabular articular surfaces are replaced by artificial materials. The introduction of this technique in the 1960s resulted from two important innovations: the development of new metal and polymer biomaterials which could provide low friction articulations while remaining inert in the body, and the use of an acrylic filling compound, or polymethylmethacrylate cement, to fix the implants to the bone. One of the earliest, and still most successful designs was that of Charnley, which replaced the femoral head with a much smaller stainless steel head on a stem fixed into the femoral shaft with acrylic cement. This articulated with a thick hemispherical socket or cup of high-density polyethylene, which was also fixed to the bone of the deepened acetabulum with acrylic cement (Fig. 17.29A). This, and similar prostheses, provided restoration of pain-free hip movement and function, which could be expected to continue for more than 10–15 years in over 90% of patients. Replacement arthroplasty is now accepted as one of the most successful operations in terms of restoring the quality of life in patients for most years. However, like all surgical procedures it has risks and complications. In the early years of its use the most feared of these was postoperative infection, either early or late. The rate of this complication has now been reduced to around 1% by the use of routine prophylactic antibiotics combined with sterile operating environments utilising clean air laminar flow ventilation. A more challenging long-term problem is the progressive aseptic loosening of the prosthetic components which may occur (Fig. 17.29B) in some patients and results in a cumulative failure rate of 1% each year. This is associated with bone destruction around the implants which was thought to result from a granulomatous tissue reaction to the wear particles liberated from the weight-bearing surfaces.

Another concept that has been reintroduced is the resurfacing or ‘double cup’ arthroplasty (Figs 17.27B and 17.30). This uses matching shells to resurface the femoral head and reline the reamed acetabular socket. Earlier attempts with this technique in the 1970s, using conventional metal and polyethylene components, had resulted in early failure because of rapid wear of the thin acetabular component. This problem has now been overcome by the use of improved metal-on-metal shells. The operation is only indicated in younger more active patients under the age of 60 where preservation of bone stock is required for potential later revision. Short-term results are now as good as with conventional replacement arthroplasty, but the operation, which is more technically demanding, should only be used for selected patients by those skilled in its use until results from longer follow-up become available.

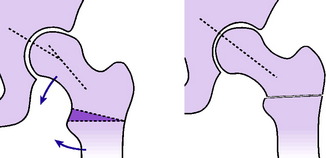

Upper femoral osteotomy (McMurray displacement osteotomy). This operation was a standard method of treatment before total replacement arthroplasty was developed, but it is now little used. It may still be useful in patients under 55 with moderately early osteoarthritis where pain is a major problem but there is still an adequate range of functional movement, including 90 ° of flexion. The femur is divided between the greater trochanter and the lesser trochanter, and the lower (shaft) fragment is displaced medially through about a quarter of its diameter (Fig. 17.28A). Internal fixation of the fragments by nail-plate and screws is usually employed. Relief of pain is often satisfactory in over 70% of patients and preoperative joint movement is retained. The question of why an upper femoral osteotomy should relieve the pain of an osteoarthritic hip has not been answered satisfactorily. It is possible that in some way the remodelling of bone trabeculae necessitated by the displacement stimulates repair processes in the damaged articular cartilage; or it may alter the vascularity of the femoral head. Certainly in a favourable case the cartilage thickens appreciably in the first two or three years after operation, as shown radiologically. The other advantage of the operation is that it can still be converted to a hip replacement arthroplasty later, should the result prove disappointing in the long term.

In excision arthroplasty (Girdlestone pseudarthrosis) a false joint is created by excising the head and neck of the femur and the upper half of the wall of the acetabulum, and suturing a mass of soft tissue (such as the gluteus medius muscle) in the gap thus created, to act as a cushion between the bones (Fig. 17.28B). This is essentially a salvage operation, originally designed for chronic infections, and should only be used when alternatives have failed or are inappropriate.

PERTHES’1 DISEASE (Legg–Perthes’ disease; coxa plana; pseudocoxalgia; osteochondritis of the femoral capital epiphysis)

Perthes’ disease is osteochondritis of the epiphysis of the femoral head. The general features of osteochondritis were described in Chapter 8(p. 130). Like most examples of osteochondritis, Perthes’ disease is an affection of childhood. The femoral head is temporarily softened and may become deformed. The main importance of the condition is that it may lead to the development of osteoarthritis of the hip in later life.

In the early phases of the cycle of changes growth of the bony element of the epiphysis is temporarily arrested, but the cartilage surrounding the bony nucleus, which forms a considerable proportion of the femoral head, continues to grow and so is disproportionately thick (Fig. 17.31), though sometimes revascularisation and healing will restore a relatively normal femoral head Fig. 17.32). Nevertheless it may sometimes follow the bone in suffering deformation, so that the femoral head as a whole may become much flattened (Fig. 17.33). At the same time there is often some enlargement of the femoral head. As the acetabulum grows, it tends to follow the contours of the femoral head, so that it may end up abnormally large and shallow (Fig. 17.34).

Fig. 17.31 Perthes’ disease of the left hip. Note the shrunken appearance of the bony nucleus of the femoral epiphysis, the corresponding increase in depth of the cartilage space, the patchy changes of density, and the suggestion of fragmentation.

In consequence of interrupted growth at the epiphysial plate the femoral neck – and the limb as a whole – may be shorter than on the normal side, though the discrepancy is not great.

Imaging. Radiographic features. The earliest radiographic changes are usually, though not always, present by the time advice is sought. There is a slight decrease in the depth of the ossific nucleus of the femoral head, whereas the clear cartilage space is often increased in depth: in other words the bony nucleus seems to have shrunk within its surrounding bed of cartilage (Fig. 17.31). The nucleus becomes denser than that of the normal side, though the density is patchy rather than uniform, so that there is an appearance of fragmentation. In severe cases the nucleus becomes progressively more flattened. Eventually the texture of the bone returns to normal (Fig. 17.32), but if flattening has occurred the femoral head is permanently deformed (Figs 17.33 and 17.34). Radioisotope scanning shows failure of uptake of the isotope in the region corresponding to the bony nucleus of the femoral head, but the changes are better demonstrated even at a very early stage by MRI scanning.

Fig. 17.32 Same patient as in Figure 17.31 two years after the onset of symptoms. The shape of the head is virtually normal, and the femoral neck is of normal length. There is little risk of osteoarthritis.

Prognosis. The disease has no direct adverse effect upon the general health. The main risk is to the future function of the affected hip joint, because if the femoral head suffers permanent deformation there is a risk of secondary osteoarthritis in later life, often in the fifth or sixth decade (Fig. 17.34).

The outcome depends largely upon whether the whole of the epiphysis is affected or whether part of it escapes, as it often does. In the latter case the prognosis is favourable (Fig. 17.32), whereas if the whole epiphysis is affected marked flattening of the femoral head may occur despite the most careful treatment (Fig. 17.33). The state of the cartilaginous part of the head, as determined from arthrography or from comparison of MRI scanning of both hips, is also important in prognosis. If head height is well preserved, the outlook is favourable, whereas if there has been early collapse of cartilage permanent deformation of the head is to be expected. In general, the outlook is more favourable in younger children than in older children.

In practice, ensuring maximal containment of the femoral head demands that the femoral head and neck (or the whole limb) must be abducted in relation to the acetabulum, to make them co-axial. This has sometimes been achieved by splinting the limbs in 20 ° or 30 ° of abduction, but the child is thus greatly handicapped in walking. Most surgeons therefore prefer to realign the femoral head and neck by dividing the femur below the greater trochanter and deflecting the neck downwards to coincide with the central axis of the acetabulum (see Fig. 17.20). Alternatively, the acetabulum itself may be redirected after osteotomy of the innominate bone (see Fig. 17.17D, p. 351).

OSTEONECROSIS (Non-traumatic avascular necrosis) OF THE FEMORAL HEAD

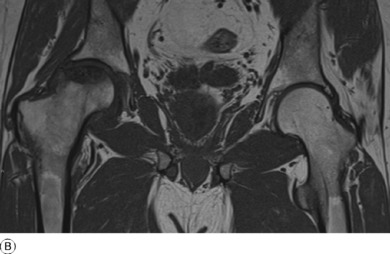

Necrosis of the bone of the femoral head may be a complication of trauma, particularly fracture of the femoral neck, but may also occur without a history of injury. This non-traumatic or idiopathic osteonecrosis is thought to be the result of an ischaemic episode affecting the bone and marrow tissue, and may cause progressive collapse of the femoral head in young adults.

Cause. The aetiology of this uncommon condition is still unclear, though several factors have been proposed as the mechanism of ischaemia, including intra-osseous hypertension, fat embolism, and intravascular coagulation. There is often a history of steroid therapy or alcohol addiction, and the condition may also develop in patients receiving immuno-suppression therapy following organ transplantation. It may also be associated with inherited haemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease; and it may occur as a complication of Gaucher’s disease (p. 72).

Investigation. In the early stage of the disease plain radiography may be normal (Fig. 17.35A), though magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show a low-intensity focus in the affected femoral head (Fig. 17.35B). Bone scintigraphy using a technetium-labelled isotope may reveal an area of increased or decreased uptake in the femoral head at the site of developing necrosis, but is less sensitive than an MRI scan.

Radiographic features. One of the earliest radiographic signs of developing osteonecrosis may be narrowing of the joint space, with flattening of the weight-bearing surface of the head and an underlying area of sclerosis in the bone. Progression to subchondral fracture results in a crescent sign of lucency beneath the superior articular surface with a dense segment in the underlying femoral head (Fig. 17.36). In the advanced stages of the disease there may be secondary arthritic changes, with progressive collapse of the femoral head.

Treatment. Treatment is usually surgical and is determined by the stage and extent of the disease. If diagnosed early, prior to femoral head collapse, an attempt can be made to encourage revascularisation by drilling the affected segment through a trans-trochanteric approach, with the possible addition of bone grafting to provide both an osteogenic stimulus and mechanical support. In more advanced disease, where some bony collapse has occurred, an osteotomy of the femoral neck may allow better containment of the femoral head and restoration of an intact articular weight-bearing surface. Once secondary osteoarthritis is established, removal of the femoral head and total replacement arthroplasty of the hip is the only surgical option.

SLIPPED UPPER FEMORAL EPIPHYSIS (Adolescent coxa vara; epiphysial coxa vara)

Cause. This is unknown. The condition is often associated with overweight from endocrine dysfunction or from other causes, but in other cases the patient is of normal build.

Pathology. The junction between the capital epiphysis and the neck of the femur loosens. With the downward pressure of weight-bearing and the upward pull of muscles on the femur the epiphysis is displaced from its normal position. Displacement is always backwards and downwards, so that the epiphysis comes to lie at the back of the femoral neck (Fig. 17.37).

Clinical features. The patient is between 10 and 20 years of age. In about half the cases there is evidence of an endocrine disturbance leading to marked overweight. In a little less than half the cases both hips are affected, though seldom simultaneously. Typically, there is a gradual onset of pain in the hip, with limp. Sometimes the pain is felt mainly in the knee, which may confuse the diagnosis. Rarely, these symptoms develop acutely after an injury, such as a fall.

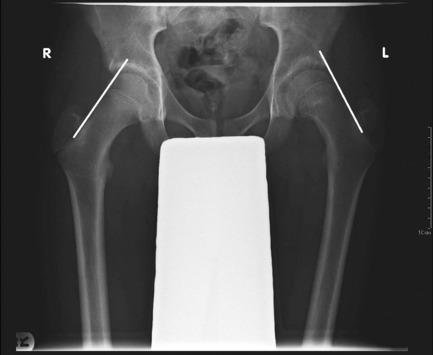

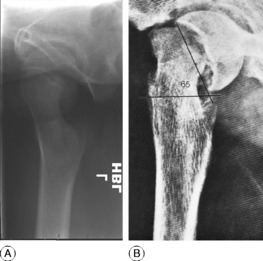

Radiographic examination. Even a slight displacement of the epiphysis is recognisable, provided good lateral radiographs are obtained. It must be stressed that a slight displacement is easily overlooked if antero-posterior films alone are examined (Fig. 17.38). Lateral radiographs are essential. In the lateral film the epiphysis is seen to be tilted over towards the back of the femoral neck (Fig. 17.39),1 the posterior ‘horn’ being lower than the anterior, whereas in the normal hip they are level.

Diagnosis. Slipped upper femoral epiphysis should be suspected in every patient of 10–20 years of age who complains of pain in the hip or knee. The characteristic clinical features, together with the radiographic evidence of epiphysial displacement, are conclusive. The condition is nevertheless often missed, partly because pain may be predominantly in the knee, the hip therefore being not examined; or because lateral radiographs are not obtained (Fig. 17.38).

If severe displacement is allowed to remain uncorrected osteoarthritis is likely to develop in later life (Fig. 17.40).

Slight displacement. When displacement is slight (less than 40 ° as measured on the lateral radiograph) (Fig. 17.39A) the position may be accepted and all that is necessary is to prevent further displacement. This is achieved by driving threaded wires or slender screws1 along the neck of the femur into the epiphysis (Fig. 17.41). It should be remembered that even though the position that has been accepted may be imperfect, improvement can occur spontaneously in the succeeding years, through a process of remodelling.

Severe displacement. When displacement is severe (Fig. 17.39B) the position cannot easily be accepted because of the virtual certainty that painful osteoarthritis will develop in adult life. The position should therefore be improved. Three methods are available: manipulation, operative replacement of the epiphysis at the site of slipping, and compensatory osteotomy at a lower level.

Manipulation, with or without preliminary weight traction, is seldom successful; it is worth trying only in the rare cases of recent sudden displacement, especially if caused by injury. Manipulation – predominantly by medial rotation – should be carried out very gently lest the blood supply to the epiphysis be further damaged. After successful manipulative reduction further slipping should be prevented by inserting threaded wires or screws, as described above.

Compensatory osteotomy is an alternative method that is preferred by most surgeons. The osteotomy is done just below the trochanteric level (Fig. 17.42). An anteriorly based wedge of bone is removed so that the shaft of the femur is angled into flexion relative to the upper fragment. The operation thus compensates for the backward tilting of the epiphysis; correction should be sufficient to bring the epiphysis once more into the weight-transmitting segment of the acetabulum. The operation entails no risk of damage to the blood supply of the femoral head, so there is no risk of disastrous avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis); but it leaves the articular surface of the upper end of the femur deformed, and therefore does not altogether remove the risk of secondary osteoarthritis in later years.

EXTRA-ARTICULAR DISORDERS IN THE REGION OF THE HIP

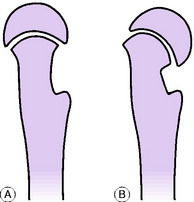

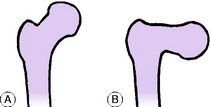

COXA VARA

The general term coxa vara includes any condition in which the neck–shaft angle of the femur is less than the normal of about 125 ° (Fig. 17.43). The angle is sometimes reduced to 90 ° or less. The deformity is caused mechanically by the stress of body weight acting upon a femur that is defective or abnormally soft.

Causes. The most important causes of coxa vara are:

Effects. Coxa vara leads to true shortening of the limb. Approximation of the greater trochanter to the ilium slackens the abductor muscles of the hip and thus impairs their efficiency, leading in severe cases to a Trendelenburg ‘dip’, with consequent limp (p. 341).

EXTRINSIC DISORDERS SIMULATING DISEASE OF THE HIP

1 Sir Thomas Smith (1833–1909) Surgeon at St.Thomas’s and Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospitals in London described acute arthritis of infants in 1874.

1 George Clemens Perthes (1869–1927), German surgeon and early pioneer of radiotherapy and the pneumatic tourniquet, identified the radiological appearance of the disease in 1898.

1 Students often have difficulty in determining in lateral radiographs of the upper end of the femur which is the back and which is the front of the bone. The key is the bony projection formed by the trochanters: this is always posterior.

1 A three-flanged nail, formerly sometimes used for fixation instead of threaded wires, is not recommended because it does not easily penetrate the hard epiphysis and may damage its blood supply.