5 The hip and pelvis

History and examination

As with any patient examination, the eliciting of a detailed and accurate history is paramount and lays the foundation for the performance of an appropriate examination and establishment of a working diagnosis and differential. The most crucial element of the history in this area of the body is the precise localization of the area of pain: many patients who complain of ‘hip pain’ do not in fact have pain in their hip and, when questioned, will point to their buttock, gluteal fold or iliac crest; similarly, patients who do have hip pathology will often complain of symptoms in their groin, or the side or front of their thigh – not infrequently described as ‘sciatica’! The use of pain diagrams can help in this regard, but, at the very least, the patient should be asked to point to where they feel pain or discomfort.1,2

With experience, the clinician will normally be able to recognize the atypical presentation of more unusual conditions such as osseous, intrapelvic and spinal lesions. These can, of course, mimic everyday injuries and the clinician should always be alert for an apparently benign condition that fails to respond to normally successful management protocols or is relentlessly progressive. Pain or clicking in the hip of a child is always a cause for concern and usually an indication for diagnostic imaging.3

Associated symptoms such as clicking or popping can also be associated with specific conditions4 and a familial history of pelvic conditions is often very revealing: many conditions such as degenerative coxarthrosis, inflammatory arthropathies, connective tissue disorders and dysplasia have familial tendencies.5–9

Examination should commence with observation of the patient both stationary and walking. Obesity (a body mass index greater than 30) is a significant predisposing factor towards coxarthrosis,10 which will often be accompanied by an obvious flexion contraction causing an inability to stand with a straightened leg on the affected side; other forms of antalgia can also help identify the source of a patient’s pain both in posture and gait.

Although there are myriad orthopaedic tests for the hips and sacroiliac joints, few have any proven validity.11–14 Range of motion, however, often is enough to demonstrate hip pathology, particularly painful reduction of internal rotation. The Patrick/FABER test (external rotation of the hip with the leg in the ‘figure-4’ position: Flexion, Abduction and External Rotation) has been shown to have good reliability as has digital palpation in the identification of greater trochanteric bursitis – the same is also true of the many myofascial trigger points that frequently coexist with pelvic girdle dysfunction and with the posterior margin of the sacroiliac joint.12,15,16

Identification of sacroiliac syndrome is more problematic; however, multiple positive provocation tests have been shown to have a measure of diagnostic reliability; these are detailed in Table 5.0117–19 alongwith tests that the authors have also found useful when similarly used in combination. It is, however, important not to perform too many tests; if three or four have already proved positive, there is little to be gained from continuing and the patient may well have an adverse reaction – the tests are called provocative for a reason and can eventually aggravate the patient’s symptoms. It should also be kept in mind that the pelvis is a closed loop kinematic chain and that comorbidity with lumbosacral facet joint dysfunction is high.20

| Multiple positives are suggestive of sacroiliac injury; if all tests are negative, injury is diagnostically eliminated | |

| Gaenslen’s test | Sit the patient on the edge of a table, flexing one leg to the chest and dropping the other to the floor |

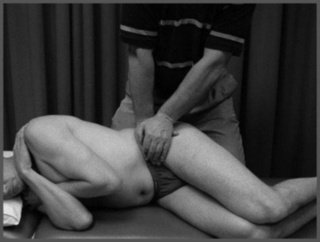

| Compression test | The ilium is forced medially against the sacrum; this is usually done with the patient lying on their side (Figure 5.01) |

| Thigh thrust | The supine patient’s hip is flexed to 90° with the knee bent and a posterior shearing force applied to the sacroilac joint through the femur avoiding hip adduction (Figure 5.02) |

| Distraction test | With the patient lying supine, the anterior superior iliac spines are pressured from lateral to medial |

| Sacral thrust | Posterior to anterior pressure is applied to the sacrum immediately adjacent to the sacroiliac joint |

| Additional sacroiliac joint tests used in combination by the authors with (apparent) success | |

| These tests are not scientifically validated; they do, however, reflect the diagnosis and successful treatment of several thousand sacroiliac joints. The tests have the advantage that they are not all provocative | |

| Yeoman’s test | Forced extension of the sacroiliac joint with the patient lying supine recreating their pain |

| Leg lift Leg lift with cervical compression |

If the patient is unable to lift both legs together when locked straight, this is indicative of sacroiliac dysfunction If they are able to perform the above test but find it much more difficult with superior to inferior pressure applied to the top of the head (thus compressing the cervical spine), this is also indicative of sacroiliac dysfunction. Either result is considered as a single positive |

| Piedallu test | The examiner places their thumbs on the posterior superior iliac spines and watches as the seated patient leans forwards. The failure of the spine to move superiorly in a symmetrical manner indicates sacroiliac dysfunction |

| Contralateral Kemp’s test | Usually Kemp’s test (forced lateral flexion with extension) is used as a test for lumbar spine disorder and will produce ipsilateral pain; however, a sacroiliac syndrome will cause contralateral pain |

| Supported Adam’s test | Patients with a sacroiliac problem often report pain on slight forward flexion (5°–15°). If the sacrum is braced against the examiner’s thigh and the ilia held firmly, the patient can flex with reduced pain and trepidation |

| Digital palpation | If there is inflammation in the sacroiliac joint, palpation along its easily identified posterior margin will usually be painful |

Differential diagnosis

Figure 5.01 • The thigh thrust sacroiliac joint provocation test.

(Reproduced from Manual Therapy17 with permission.)

Figure 5.02 • The compression sacroiliac joint provocation test.

(Reproduced from Manual Therapy17 with permission.)

When it comes to the hip joint, the main aim of the differential diagnosis is to distinguish between intra-articular pathology, extra-articular pathology, and those conditions that can mimic hip pain. These are summarized in Table 5.02.3,21,22

| Intra-articular | Extra-articular | Mimickers |

|---|---|---|

The clinician should also be alert for paediatric cases presenting as knee pain without discernible cause. Two common hip conditions often present in this manner: slipped capital femoral epiphysis and Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease, and both have prognosis directly related to early detection.23

Technique and protocols

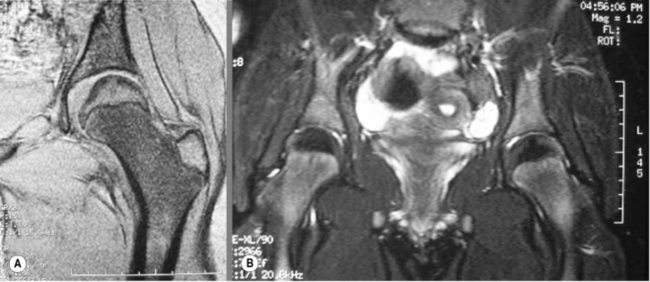

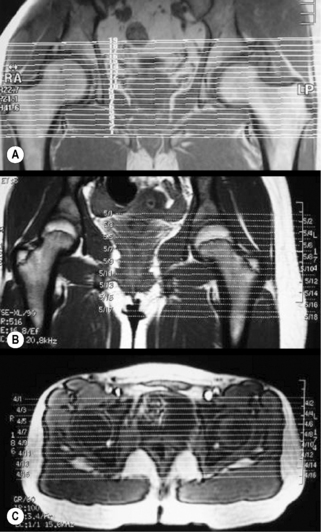

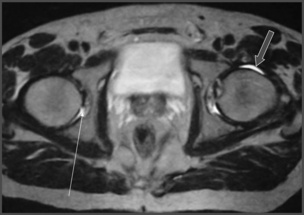

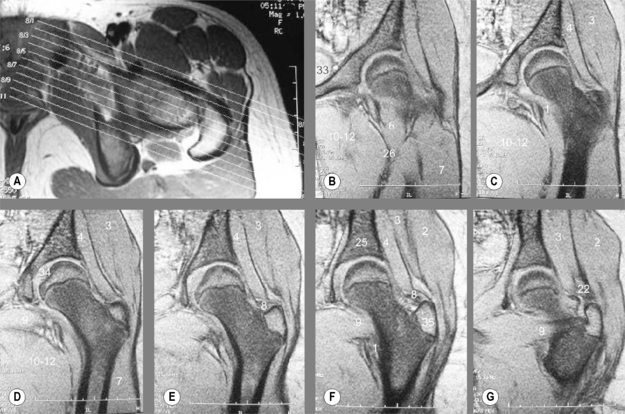

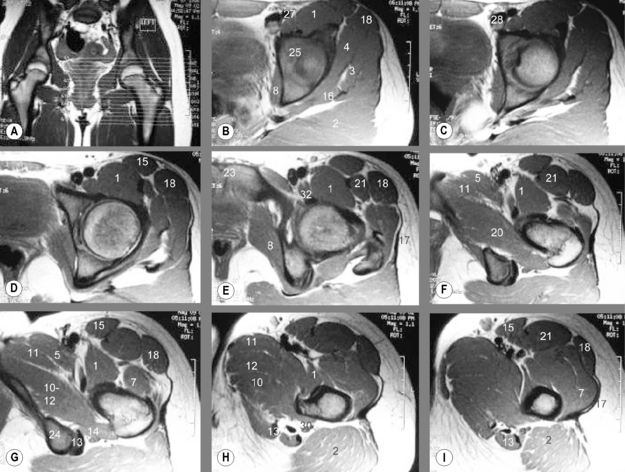

During any MR imaging evaluation, patient co-operation is critical. For evaluation of the hip, the patient should lie supine with mild internal rotation of the feet. Symmetry of rotation of both feet is important when both joints are examined simultaneously, which they often are to compare the appearance of the trochanters and adjacent muscles.24–26 Two types of images are available: a screening examination of both hips, or a higher-detail study of a single joint (Figure 5.03).

The study begins with a plan scan (or ‘scout’ view) through the level of the femoral head and will usually include axial and coronal views (Figure 5.04). T1-weighted and fluid-sensitive images will be obtained in multiple planes. Depending on the pathology suspected, sagittal views may also be acquired (Figure 5.05). Fat-suppression techniques are very commonly used in the hip and pelvis to show early changes in marrow signal.24,25,27,28

Intravenous contrast is not routinely utilized but may be helpful to differentiate cystic from solid masses or early ischaemic changes and in the evaluation of labral pathologies that have proven inconclusive on normal MR protocols. In these situations, findings may be accentuated even more if paired with fat-suppression techniques.25,27,29,30

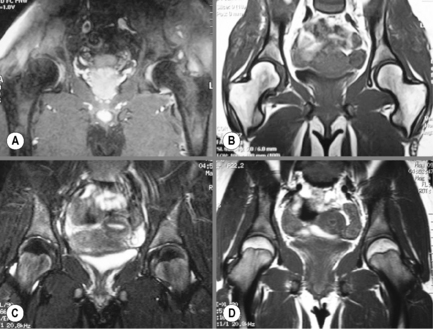

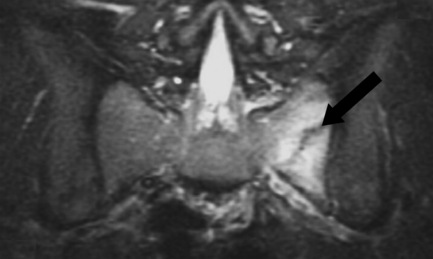

Evaluation of the sacrum, sacroiliac joint and superior bony pelvis anatomy requires different positioning for the patient and should be ordered separately. The patient is often asked to lie supine with the knees slightly bent and hip joint mildly flexed; this position precludes good visualization of the iliofemoral joint. The planes of imaging for these areas is also different; in cases where sacroiliac arthropathy is suspected, images obtained in an oblique coronal plane parallel to the joint may be helpful (Figure 5.06). Intravenous administration of contrast can help identify early sacroiliitis. If pathology is suspected in the posterior soft tissues, imaging in the prone position may be also considered, to limit compression of the soft tissues.24,25,27,31,32

Normal anatomy and common variants

MR imaging displays osseous and soft tissue structures with great clarity; the osseous anatomy is best evaluated on the T1-weighted sequences. The acetabular fossa is a deep pocket that covers approximately 40% of the surface of the femoral head. The thick fibrocartilaginous labrum and transverse acetabular ligament completely encircle the acetabulum. Both structures will be demonstrated as low intensity areas on most of the MR sequences.33

The femoral head is generally spherical and covered by articular cartilage with the exception of the insertion point of the ligamentum teres: the fovea centralis. Covering the proximal femur is the articular capsule extending from the supra-acetabular region to the femoral neck.34,35 It is a normal finding to see a small amount of fluid inside the joint space (Figure 5.07). Adjacent to the capsule is one of the largest synovial bursae of the body: the iliopsoas bursa. It is seen as a high intensity area on fluid-sensitive images, sandwiched between the muscle and the capsule. In a small percentage of the population, it may even communicate with the joint.36 MR imaging allows for assessment of the major muscle groups surrounding the hip articulation: the external rotators inserting on the greater trochanter, and iliopsoas attaching to the lesser trochanter and the hip flexors crossing over the large joint (Figures 5.08, 5.09; Box 5.01).22,33

Figure 5.08 • MR imaging demonstrating coronal gradient echo images of the left hip of a 13-year-old girl (A–G). The images are displayed following the scout view (A), from anterior (B) to posterior (G) to depict various normal anatomical structures. Note the degree of detail attained on these images, including the individual muscle groups. The key to the images is detailed in Box 5.01.

Figure 5.09 • MR imaging demonstrating axial proton density images of the hips of a 13-year-old girl (A–I). The images are displayed from superior (A) to inferior (I) from the supra-acetabular ridge to the diaphysis of the femur. A variety of anatomical structures are depicted on the views. The key to the images is detailed in Box 5.01.

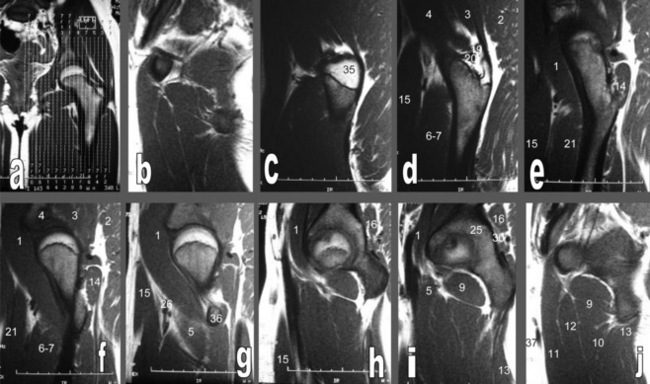

In the pelvis and proximal femur, the composition of the bone marrow varies with age, skeletal maturity and health status, and the MR imaging appearance will change accordingly (Figure 5.10). In the adult, bone marrow throughout the pelvis and femoral head will demonstrate intermediate signal intensity, slightly more intense than the muscle, on T1-weighted images; the marrow in adults is generally composed of fatty components. The signal may however be heterogeneous and patchy, interrupted by low signal zones on T1 images, representing residual foci of haematopoietic (red) marrow. These are considered normal findings and are generally bilateral and symmetrical. Abnormality is represented by the persistence of red marrow in the epiphysis and should lead to further investigation. In children, the marrow patterns vary by region. The femoral head and greater trochanter will contain yellow marrow and the intertrochanteric or metaphyseal region will contain haematopoietic marrow (Figure 5.11).24,28,29,37

Figure 5.11 • Sagittal, fast spin echo T1-weighted MR images of a 13-year-old girl (A–J). The images are displayed from lateral (A) to medial (J), beginning at the outer aspect of the greater trochanter and continuing medially to the ilium. In this young patient, the femoral head exhibits high signal intensity on the T1-weighted image since it contains yellow marrow and the intertrochanteric or metaphyseal region is of a lower signal intensity since it contains haematopoietic marrow. The key to the images is detailed in Box 5.01.

Other causes of marrow signal abnormalities include bone islands. They are easily recognized as decreased signal zones on all sequences and are frequently found in the proximal femur (Figure 5.12).27,38 Obliquely oriented linear zones of decreased signal intensity in the femoral neck may also be seen and represent the bony weight-bearing trabecular groups. Well-defined areas of abnormal low T1-weighted and high T2-weighted signal intensity may be present in the anterior-lateral portion of the femoral neck. Synovial herniation pit defects are also common in this location and can be recognized by the presence of focal increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images, a sclerotic margin, focal central radiolucency and their characteristic location. Accurate identification is dependent on correlation with other studies such as plain film radiography.39

Multiple acetabular labral shapes have been described; however, 66%–80% of normal acetabular labra are triangular other than in the posterosuperior portion, which is typically flat, a finding which is generalized in 9% of individuals. A round labrum appears to be a normal variant and is seen in 11%–13% of individuals, whilst up to 7% have irregular labra. The structure is absent in up to 14% of individuals. No correlation between labral shape and injury or degeneration has been established. The labrum will demonstrate low signal intensity on most MR imaging sequences.40–43

Pathological findings

Avascular necrosis

One of the major indications for MR imaging of the pelvis and hip is to investigate the possibility of avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head. MR imaging is very sensitive in the early detection of this condition.24,25,27

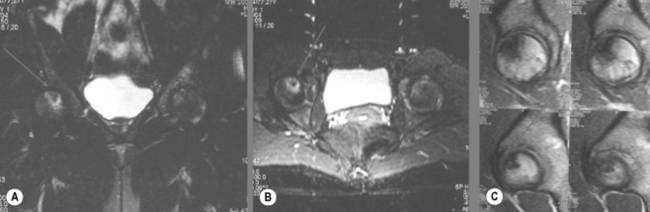

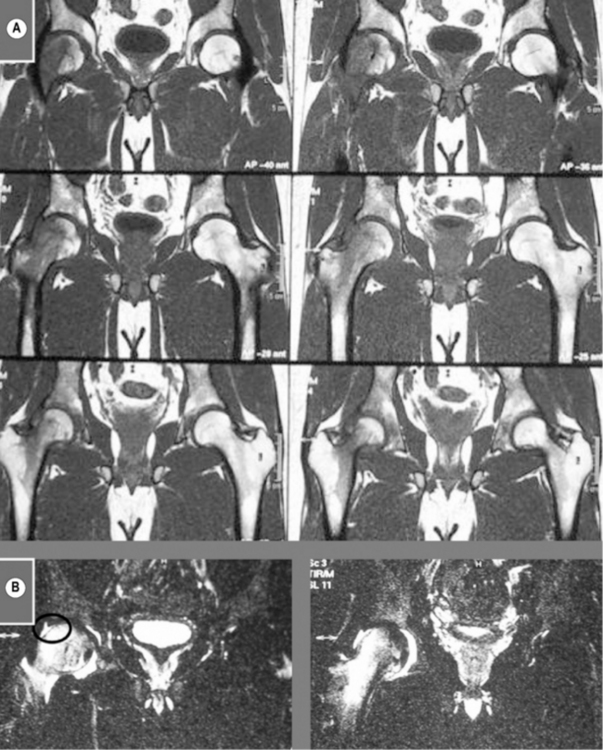

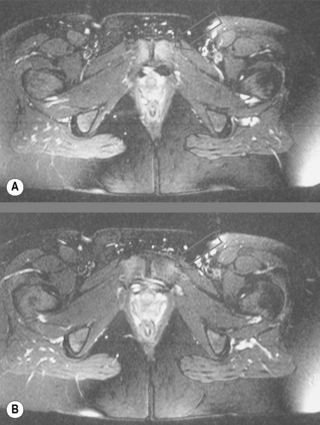

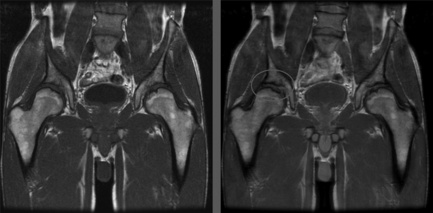

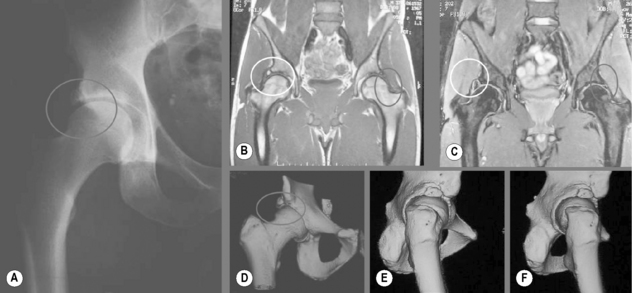

The risk factors for AVN are multiple and include trauma, corticosteroids (endogenous or exogenous), haemoglobinopathies, alcoholism, pancreatitis, Gaucher’s disease, radiation treatment and dysbaric injury. The clinical presentation also varies greatly; however, when suspected, careful examination of both hips should be performed since bilateral presentation may be seen in up to 40% of patients (Figure 5.13).44–46

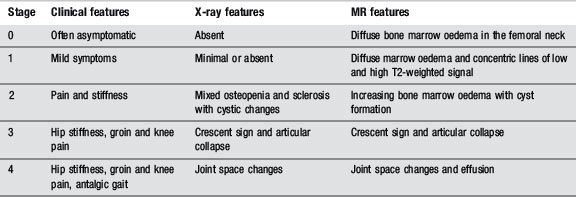

Avascular necrosis can be classified using clinical, radiographic or MR criteria (Table 5.03). The changes seen in stage 1, which is almost invariably latent on plain films, represent the hypovascular area surrounding the necrosis. The shape of the femoral head and integrity of the joint space remain intact until stage 3. Although, at this stage, plain films are sufficient to detect AVN, the degree of bone marrow oedema demonstrated on MR images correlates quite strongly to the levels of reported pain.47–49 Even though specific measurements are not available, it is important to realize that the normal amount of fluid in the capsule is generally not sufficient to generate signal changes on T2-weighted images, making any high signal intensity area in the joint clinically suspicious.25,29,50

Trauma

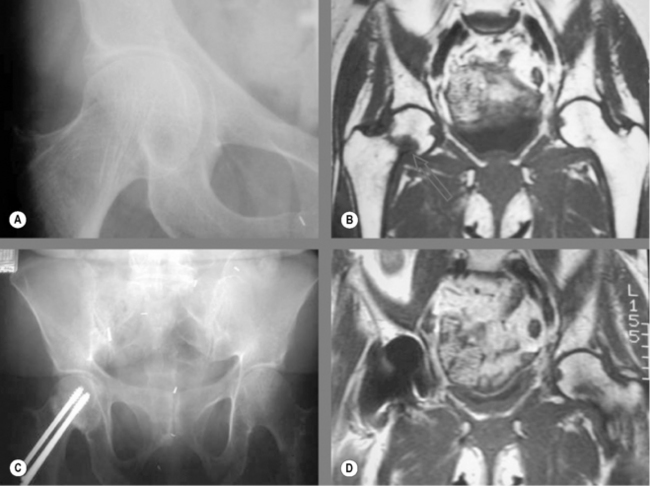

Dislocations of the hip joint usually only occur following severe trauma and are associated with lesions of the femoral head, labrum and acetabulum. Bone bruises on either the femoral head/neck or acetabulum may be visualized as areas of decreased T1-weighted and increased T2-weighted signal zones adjacent to the area of impact (Figures 5.14, 5.15).24,25,27

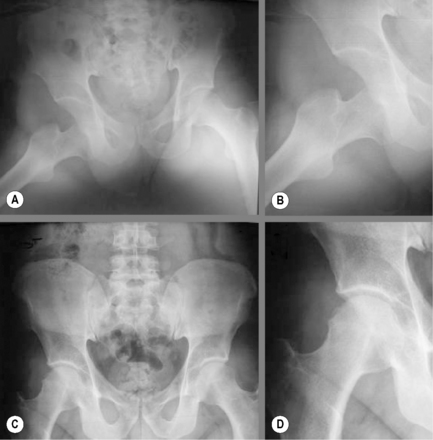

Figure 5.14 • Plain film hip radiographs of a gentleman who sustained a rally car accident involving several rolls of the car. The initial imaging demonstrates dislocation of the right hip (A and B). The patient was recommended to remain immobile for 2 months before resuming normal activities having had the articulation relocated; however, he was still limited by hip pain which was worsening. Follow-up imaging was performed (C and D), which demonstrated an irregularity and deformity about the lateral aspect of the femoral head as well as joint effusion (note the displaced gluteus medius fascial plane). Owing to the previous trauma and the imaging and examination findings, MR imaging was ordered (Figure 5.15).

(This case is reproduced courtesy of Vincent Klingelschmitt DC, France.)

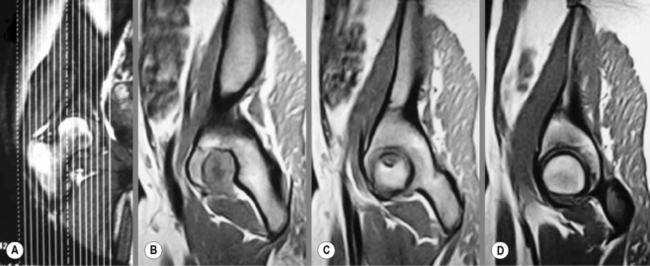

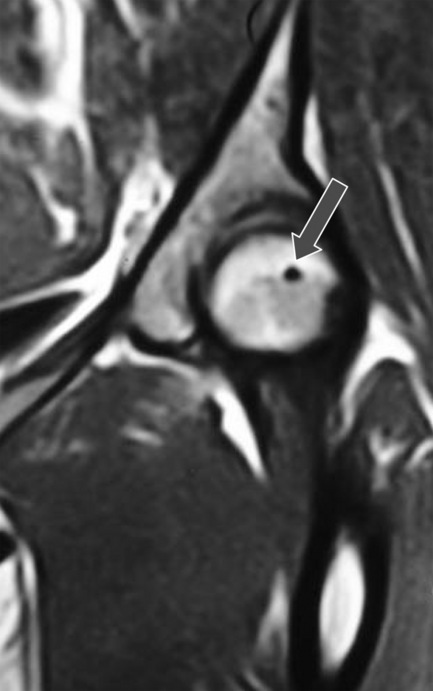

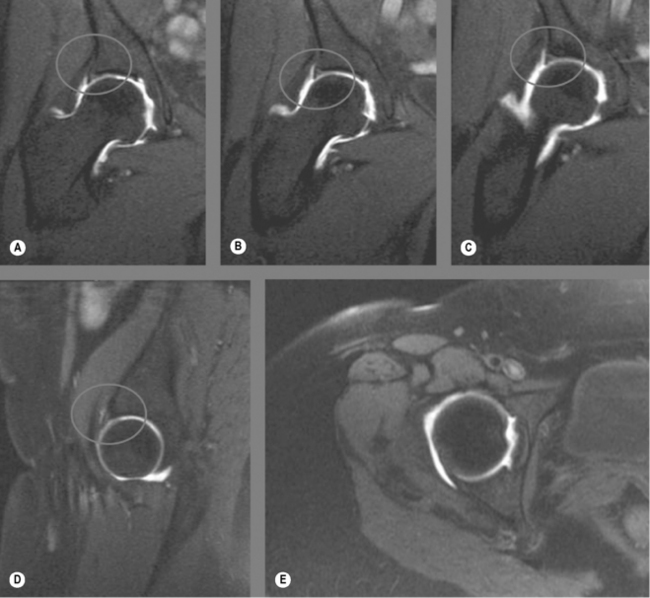

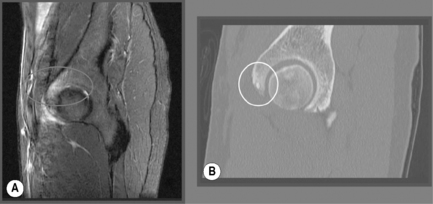

Injuries to the fibrocartilaginous labrum may occur with dislocations or be associated with degenerative processes. They can be difficult to identify on non-contrasted sequences or to differentiate from benign individual variation. Tears may appear as irregularities in the surface as well as focal increases in signal intensities; they may also be associated with cysts. Clicking, snapping, decreased ranges of motion and deep hip pain, aggravated by hip rotation and flexion, are the most common clinical symptoms (Figure 5.16).51–53

MR imaging has largely replaced bone scintigraphy as the most effective tool for detecting stress or insufficiency injuries; it can detect changes 24 to 48 hours prior to any other type of imaging modality.25,54 Insufficiency fractures from biomechanical stresses on weakened bone are common and often radiographically occult. A painful hip in a patient at risk for osteoporosis should always raise clinical suspicion of fracture, even if the patient remains weight-bearing and has no significant history of trauma. In these cases, a limited MR examination may be requested. Coronal and axial T1-weighted and T2-weighted fat-suppressed images of the entire pelvis may show the fracture site as a linear low signal area with surrounding bone marrow oedema. Careful evaluation of the entire pelvis is essential to eliminate concurrent sacral or ischiopubic fractures (Figures 5.17, 5.18).24,25,27,54–56

Stress fractures from increased or abnormal stress on normal bone may also be assessed with MR imaging before findings are visible on radiographs. A linear, hypointense zone will be surrounded by a hyperintense bone marrow oedema on T2-weighted images as a response to the stress. Bone marrow oedema and articular irregularities along the pubic symphysis may indicate increased stress in this region; this condition is seen in athletes. It is often referred to as osteitis pubis and will present clinically as groin pain (Figure 5.19).25,57,58

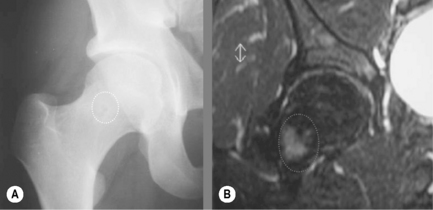

Synovial herniation pits

Pit herniation defects (also known as synovial herniation pits or Pitt’s pits) represent a well-rounded abnormality in the cortex of the femoral neck in the upper, outer quadrant and are filled with fibrous and cartilaginous elements. On plain film, their appearance will be of a small, radiolucent lesion with a well-defined sclerotic rim; on MR imaging, a low focus on T1-weighted and high focal signal intensity on T2-weighted images will be seen.24,25,27,59

These lesions were thought to be clinically silent and stable; however, there are now multiple reports of expanding, painful lesions and, indeed, synovial herniation pits are now known to be associated with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (Figure 5.20). Clinically, this entity may mimic a labral injury: clicking and pain during normal range of motion, and may predispose to early degenerative changes.60 Femoroacetabular impingement can be seen in patients with a history of acetabular deformity: developmental dysplasia (Figure 5.21); femoral defects, such as AVN; and slipped capital femoral epiphysis, or in patients with activities involving repetitive hip flexion, rotation and abduction.61–65 Accessory ossicles such as os acetabulae are also known associated imaging findings (Figure 5.22).66

Tumours

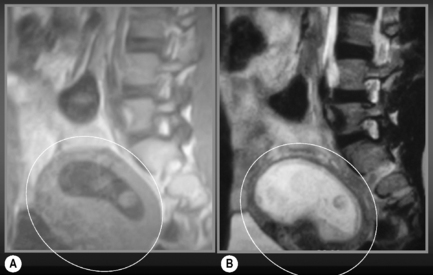

The pelvis and proximal femur are common locations for musculoskeletal tumours in patients of any age; these entities can also alter signal patterns. Neoplasms can present as a decreased T1-weighted and increased T2-weighted signal. This represents an inflammatory response but does not differentiate between benign or malignant; primary or secondary. It is generally accepted that the greater value of MR imaging is in the staging of tumours as opposed to their diagnosis, which often can be better accomplished with conventional radiographs. Common tumour or tumour-like conditions in the pelvis include many conditions such as metastatic disease, osteochondroma, fibrous dysplasia, Paget’s disease and osteoid osteoma (Figure 5.23).24,25,27

Obstetrics

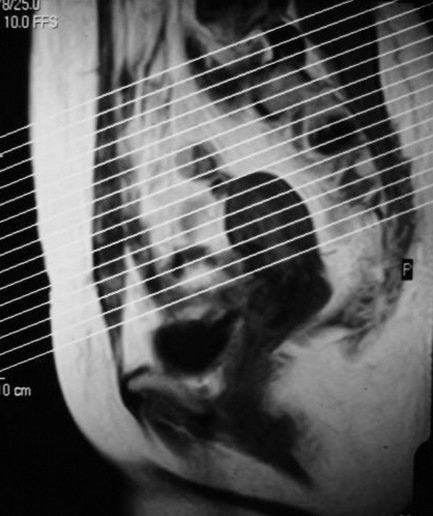

In recent years, applications for obstetrical imaging have been developed. Although ultrasonography remains the imaging modality of choice during pregnancy, MRI provides excellent resolution and tissue contrast for evaluation of both mother and fetus without the use of ionizing radiation (Figure 5.24). The first trimester remains a relative contraindication for MR imaging owing to the lack of information regarding the long-term effects.67,68

1 Bates B. The musculoskeletal system. In: Bates B., editor. A Guide to Physical Examination. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1983:324-370.

2 Bates B., Hoekelman R. Interviewing and the health history. In: Bates B., editor. A Guide to Physical Examination. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1983:1-27.

3 Tibor L.M., Sekiya J.K. Differential diagnosis of pain around the hip joint. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(12):1407-1421.

4 Blankenbaker D.G., Tuite M.J. Iliopsoas musculotendinous unit. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2008;12(1):13-27.

5 Beers M., Berkow R. Temporomandibular disorders. In The Merck Manual, 17th ed, West Point, PA: Merck & Co; 1999:772-776.

6 Valdes A.M., Spector T.D. The contribution of genes to osteoarthritis. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(1):45-66. x

7 Malagon V. Development of hip dysplasia in hereditary multiple exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(2):205-211.

8 Pailthorpe C.A., Benson M.K. Hip dysplasia in hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(4):538-540.

9 Mau H. Familial hip dysplasia with short acetabular roofs. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1988;126(2):156-160.

10 Andersen R.E., Crespo C.J., Bartlett S.J., et al. Relationship between body weight gain and significant knee, hip, and back pain in older Americans. Obes Res. 2003;11(10):1159-1162.

11 Martin R.L., Irrgang J.J., Sekiya J.K. The diagnostic accuracy of a clinical examination in determining intra-articular hip pain for potential hip arthroscopy candidates. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):1013-1018.

12 Martin R.L., Sekiya J.K. The interrater reliability of 4 clinical tests used to assess individuals with musculoskeletal hip pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(2):71-77.

13 Dreyfuss P., Dreyer S.J., Cole A., Mayo K. Sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(4):255-265.

14 Weksler N., Velan G.J., Semionov M., et al. The role of sacroiliac joint dysfunction in the genesis of low back pain: the obvious is not always right. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(10):885-888.

15 Travell J., Simons D. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1992.

16 Paydar D., Thiel H., Gemmell H. Intra and interexaminer reliability of certain palpatory procedures and the sitting flexion test for sacroiliac joint mobility and dysfunction. J Neuromusc Sys. 1994;2(2):65-69.

17 Laslett M., Aprill C.N., McDonald B., Young S.B. Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10(3):207-218.

18 Laslett M., Williams M. The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology. Spine. 1994;19(11):1243-1249.

19 Kokmeyer D.J., Van der Wurff P., Aufdemkampe G., Fickenscher T.C. The reliability of multitest regimens with sacroiliac pain provocation tests. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2002;25(1):42-48.

20 Young M.F. The physics of anatomy. In: Essential Physics for Musculoskeletal Medicine. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2009.

21 Ferri F.F. Ferri’s Differential Diagnosis. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2005.

22 Eustace S., Johnston C., O’Neill P., O’Byrne J. Sports Injuries: Examination, Imaging and Management. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007.

23 Beers M., Berkow R. The Merck Manual, 17th ed. West Point, PA: Merck & Co, 1999.

24 Stoller D. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1996.

25 Berquist T. MRI of the Musculoskeletal System, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000.

26 Mirowitz S. Pitfalls, Variants And Artifacts in Body MR Imaging. St Louis: Mosby, 1996.

27 Kaplan P., Helms C., Dussault R., Anderson M. Musculoskeletal MRI. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

28 Dawson K.L., Moore S.G., Rowland J.M. Age-related marrow changes in the pelvis: MR and anatomic findings. Radiology. 1992;183(1):47-51.

29 Stoller D.W., Tirman P.F., Bredella M.A. Diagnostic Imaging Orthopaedics. Salt Lake City: Amirsys Inc, 2003.

30 Docherty P., Mitchell M.J., MacMillan L., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of sacroiliitis. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(3):393-401.

31 Hodler J., Yu J.S., Goodwin D., et al. MR arthrography of the hip: improved imaging of the acetabular labrum with histologic correlation in cadavers. Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(4):887-891.

32 Braun J., Golder W., Bollow M., et al. Imaging and scoring in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(6 suppl 28):S178-S184.

33 Standring S., editor. Gray’s Anatomy – Pelvic girdle and lower limb – pelvic girdle, gluteal region and hip joint (Section 111). Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2009.

34 Moore K. The perineum and pelvis. In Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 2nd ed, Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1985:298-395.

35 Green J., Silver P. The pelvis. In: An Introduction to Human Anatomy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1981:224-253.

36 Wunderbaldinger P., Bremer C., Schellenberger E., et al. Imaging features of iliopsoas bursitis. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(2):409-415.

37 Levine C.D., Schweitzer M.E., Ehrlich S.M. Pelvic marrow in adults. Skeletal Radiol. 1994;23(5):343-347.

38 Greenspan A. Bone island (enostosis): current concept – a review. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(2):111-115.

39 Nokes S.R., Vogler J.B., Spritzer C.E., et al. Herniation pits of the femoral neck: appearance at MR imaging. Radiology. 1989;172(1):231-234.

40 Lecouvet F.E., Vande Berg B.C., Malghem J., et al. MR imaging of the acetabular labrum: variations in 200 asymptomatic hips. Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(4):1025-1028.

41 Hachiya Y., Kubo T., Horii M., et al. Characteristic features of the acetabular labrum in healthy children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10(3):169-172.

42 Aydingoz U., Ozturk M.H. MR imaging of the acetabular labrum: a comparative study of both hips in 180 asymptomatic volunteers. Eur Radiol. 2001;11(4):567-574.

43 Abe I., Harada Y., Oinuma K., et al. Acetabular labrum: abnormal findings at MR imaging in asymptomatic hips. Radiology. 2000;216(2):576-581.

44 Watson R.M., Roach N.A., Dalinka M.K. Avascular necrosis and bone marrow edema syndrome. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42(1):207-219.

45 Bachiller F.G., Caballer A.P., Portal L.F. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head after femoral neck fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002:399:87-109.

46 Mirzai R., Chang C., Greenspan A., Gershwin M.E. The pathogenesis of osteonecrosis and the relationships to corticosteroids. J Asthma. 1999;36(1):77-95.

47 Ito H., Matsuno T., Minami A. Relationship between bone marrow edema and development of symptoms in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(6):1761-1770.

48 Mitchell D.G., Rao V.M., Dalinka M., et al. Hematopoietic and fatty bone marrow distribution in the normal and ischemic hip: new observations with 1.5-T MR imaging. Radiology. 1986;161(1):199-202.

49 Huang G.S., Chan W.P., Chang Y.C., et al. MR imaging of bone marrow edema and joint effusion in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head: relationship to pain. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(2):545-549.

50 Mitchell D.G., Rao V., Dalinka M., et al. MRI of joint fluid in the normal and ischemic hip. Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146(6):1215-1218.

51 Blankenbaker D.G., Tuite M.J. The painful hip: new concepts. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35(6):352-370.

52 Toomayan G.A., Holman W.R., Major N.M., et al. Sensitivity of MR arthrography in the evaluation of acetabular labral tears. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(2):449-453.

53 Schmid M.R., Notzli H.P., Zanetti M., et al. Cartilage lesions in the hip: diagnostic effectiveness of MR arthrography. Radiology. 2003;226(2):382-386.

54 Lubovsky O., Liebergall M., Mattan Y., et al. Early diagnosis of occult hip fractures MRI versus CT scan. Injury. 2005;36(6):788-792.

55 Verbeeten K.M., Hermann K.L., Hasselqvist M., et al. The advantages of MRI in the detection of occult hip fractures. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(1):165-169.

56 Frihagen F., Nordsletten L., Tariq R., Madsen J.E. MRI diagnosis of occult hip fractures. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(4):524-530.

57 Rodriguez C., Miguel A., Lima H., Heinrichs K. Osteitis pubis syndrome in the professional soccer athlete: a case report. J Athl Train. 2001;36(4):437-440.

58 Brennan D., O’Connell M.J., Ryan M., et al. Secondary cleft sign as a marker of injury in athletes with groin pain: MR image appearance and interpretation. Radiology. 2005;235(1):162-167.

59 Rowe L., Yochum T., editors. Essentials of Skeletal Radiology, 2nd ed, Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 2004.

60 Kassarjian A., Belzile E. Femoroacetabular impingement: presentation, diagnosis, and management. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2008;12(2):136-145.

61 Kassarjian A., Brisson M., Palmer W.E. Femoroacetabular impingement. Eur J Radiol. 2007;63(1):29-35.

62 Murphy S., Tannast M., Kim Y.J., et al Debridement of the adult hip for femoroacetabular impingement: indications and preliminary clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:429:178-181.

63 Beall D.P., Sweet C.F., Martin H.D., et al. Imaging findings of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(11):691-701.

64 Hart E.S., Metkar U.S., Rebello G.N., Grottkau B.E. Femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents and young adults. Orthop Nurs. 2009;28(3):117-124. quiz 25–26

65 Allen D., Beaule P.E., Ramadan O., Doucette S. Prevalence of associated deformities and hip pain in patients with cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(5):589-594.

66 Hergan K., Oser W., Moriggl B. Acetabular ossicles: normal variant or disease entity? Eur Radiol. 2000;10(4):624-628.

67 Brown M.A., Birchard K.R., Semelka R.C. Magnetic resonance evaluation of pregnant patients with acute abdominal pain. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005;26(4):206-211.

68 Thompson S.K., Goldman S.M., Shah K.B., et al. Acute non-traumatic maternal illnesses in pregnancy: imaging approaches. Emerg Radiol. 2005;11(4):199-212.