CHAPTER 7 The Great Debate

What is it about opposites that so fascinates us?

Men and women? Beyond the scope of this book. Beyond the scope of any book, if you think about it.

The truth lies somewhere in between.

MONEY

Dr. Jekyll—Simulators are worth the money.

Unsuccessful lawsuit—well, you pick whatever number you want. The jury surely will.

“But this is all speculative!” the cynic says.

An insurance company asking for less money. When was the last time you heard of that? The insurance companies are saying, in a concrete way, “Simulator training is a worthy financial investment.”

That’s the “Dummies Guide to Amortization.”

Didn’t make enough money on the 70s party?

Who knows? You are limited only by your imagination.

Mr. Hyde—Simulators are not worth the money.

No “Simulator champion” ever looks at what else you could do with all that money.

OK, fine, you say, but what about all that money we were going to make in the Simulator?

Unconvinced? Mr. Hyde has other financial arguments against Simulators.

EDUCATION

Dr. Jekyll—Simulators are the way to educate.

Educational theory shows that Simulators are the way to go in education. Most learning occurs in the dull and dreary confines of the lecture hall or the library. The student gets no emotional attachment to the lesson, so the learning goes in one ear (or eye) and out the other.

Now, give that same lesson in the Simulator and put an emotional tag on the lesson.

Another lesson gleaned from the educational experts?

How about other, rarer conditions, such as malignant hyperthermia or thyroid storm?

How about the less exotic conditions? The basic problems that plague anesthesia everyday?

Back to broader educational theory.

Take a concrete example to clarify the issue.

Pop! The lung gets hit and goes down.

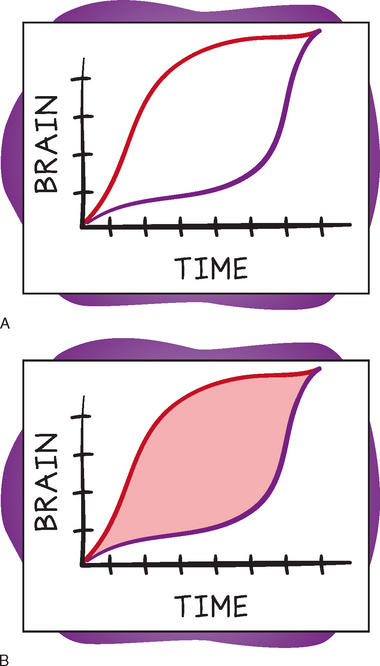

By the time the non-Simulator person sees it and recognizes it, the patient has gone onto a tension pneumothorax and is in big trouble, going on to arrest. The Simulator person sees it a little earlier, reacts a little faster, avoids the tension pneumothorax and the arrest.

From a bunch of angles, Simulation is an educational yes. Simulation is an educational Dr. Jekyll.

ACCREDITATION

Dr. Jekyll—We should make board certification a “Simulator event.”

Shouldn’t you prove this? Have half the pilots prove themselves in the simulator, which leaves a control, untested group. Then, to ensure scientific validity, do this with thousands of pilots, and make sure enough people die so the statistics are clean. Once that tenth 747 plunges out of the sky into a packed baseball stadium, you should be able to draw a superb scientific conclusion with a P value of less than 0.05!

So why not do this in anesthesia too?

Not in theory, actually do it!

This is not such a stretch, by any means.

The Simulator as accreditation mechanism is a Dr. Jekyll all the way.

Mr. Hyde: We should not make board certification a “Simulator event.”

What, our current system isn’t good enough? Who says so? Before someone can even sit for their written exam, they have to pass three steps of the written medical boards, then they have to go through an ACGME-approved internship, then an ACGME-approved residency. And no one is evaluating their ability to handle hypoxemia, hypercarbia, light anesthesia, or dysrhythmias during all these years of training? Please!

Now let’s throw a Simulator into the deal. Oh, that should go swimmingly!

The logistics start to go super-nova.

And upon this rock, you build your certification church?

On the flip side, it’s easy to imagine a poor practitioner in the “real world” doing quite well in the Simulator, particularly if he or she had a lot of practice with it. Stretch your imagination a little and picture this—to make absolutely sure I pass my Simulator exam, I’ll take off 3 months, never do any cases, and just “practice in the Simulator until I have it all down pat.”

I myself would not want this person taking care of my child.