Chapter 14 The gastrointestinal and biliary system

Diarrhoea

The first line treatment is oral rehydration therapy using sugar-salt solutions, often with added starch, and the use of gruel rich in polysaccharides (e.g. rice or barley ‘water’) is an effective measure. The polysaccharides of rice (Oryza sativa) grains are hydrolysed in the GI tract; the resulting sugars are absorbed because the co-transport of sugar and Na+ from the GI lumen into the cells and mucosa is unaffected. Rice suspensions thus actively shift the balance of Na+ towards the mucosal side, enhance the absorption of water and provide the body with energy, and the efficacy of rice starch has been demonstrated in several clinical studies. The treatment of diarrhoea in adults, particularly for travellers, may also include opiates or their derivatives, to reduce gastrointestinal motility. Many classical anti-diarrhoeal preparations contain opium extracts, or the isolated alkaloids morphine and codeine (e.g. kaolin and morphine mixture, codeine phosphate tablets), although these are controlled by law in some countries. Opioid derivatives such as loperamide, which have limited systemic absorption and, therefore, fewer central nervous system side effects, have superseded these agents to some extent but the natural substances are still used and are highly effective. Dietary fibre, including that found in bulk-forming laxatives (qv) can also be used to treat diarrhoea; in this case, the fibre is taken with only a small amount of water. There are other plant drugs which act in varying ways (for review see Palumbo 2006).

Tannin-containing drugs

Tannins are astringent, polymeric polyphenols, and are found widely in plant drugs. The most important herbs used in the treatment of diarrhoea include Greater Burnet, Sangisorba officinalis L., Black Catechu, Acacia catechu Willd., Oak bark, Quercus robur L., Tormentil, Potentilla erecta (L.) Rausch., and even tea and coffee; however, many others are used in different countries (Palumbo 2006). Tannin-containing drugs are generally safe, but care should be taken with concurrent administration of other drugs since tannins are not compatible with alkalis or alkaloids, and form complexes with proteins and amino acids.

Constipation

Bulk-forming laxatives

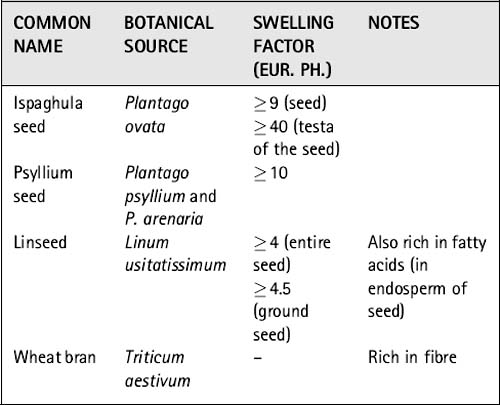

Bulking agents can be distinguished from swelling agents in that bulking material contains large amounts of fibre, whereas swelling material is generally composed of plant material (seeds) with a dense cover of polysaccharides on the outside. Both types of medicinal drugs may swell to a certain degree by the uptake of water, but swelling agents in the strict sense include only medicinal plants that form mucilage or gel. The swelling factor (which compares the volume of drug prior to and after soaking it in water) is an indicator of the amount of polysaccharides present in the drug and is generally used as a marker for the quality of bulk-forming laxatives. The European Pharmacopoeia requires a minimal value of the swelling factor for each agent, and the swelling factors of the phytomedicines detailed below are shown in Table 14.1. Preparations of bulk-forming laxatives are always taken with plenty of water. They can, paradoxically, be used to treat diarrhoea if given with very little fluid; they then absorb the fluid from the lumen and increase the consistency of the stool.

Stimulant laxatives

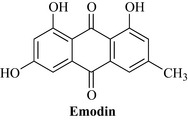

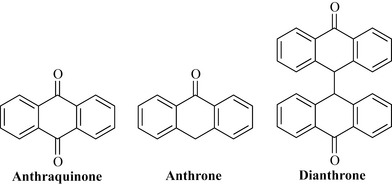

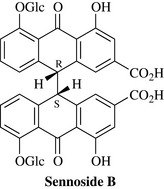

Stimulant laxatives are derived from a variety of unrelated plant species, which only have in common the fact that they contain similar chemical constituents. These are anthraquinones such as emodin (Fig. 14.1) and aloe-emodin, and related anthrones and anthranols. Anthraquinones are commonly found as glycosides in the living plant. Several groups are distinguished, based on the degree of oxidation of the nucleus and whether one or two units make up the core of the molecule. The anthrones are less oxygenated than the anthraquinones and the dianthrones are formed from two anthrone units (Fig. 14.2). Studies using dianthrone glycosides such as sennosides A and B suggest that most of these compounds pass through the upper GI tract without any change; however, they are subsequently metabolized to rhein anthrone in the colon and caecum by the natural flora (mainly bacteria) of the GI tract. Anthranoid drugs act directly on the intestinal mucosa, influencing several pharmacological targets, and the laxative effect is due to increased peristalsis of the colon, reducing transit time and, consequently, the re-absorption of water from the colon. Additionally, the stimulation of active chloride secretion results in an inversion of normal physiological conditions and a subsequent increased excretion of water. Overall, this results in an increase of the faecal volume with an increase in the GI pressure. These actions are based on the well-understood effects of chemically defined constituents; consequently, phytomedicines containing them are usually standardized to specified anthranoid content (see Chapter 9).

Frangula, Rhamnus frangula L. (Frangulae cortex); buckthorn, R. cathartica L. (Rhamni cathartici cortex) and cascara, R. purshiana DC. (Rhamni purshiani cortex)

Constituents

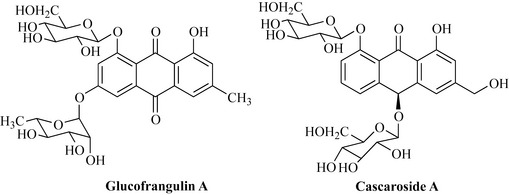

R. frangula. Glucofrangulin A (Fig. 14.3) and B, which are diglucosides differing only in the type of sugar at C6.

R. cathartica. Emodin, aloe-emodin, chrysophanol and rhein glycosides, frangula-emodin, rhamnicoside, alaterin and physcion.

R. purshiana. Cascarosides A (Fig. 14.3), B, C, D, E and F (which are stereoisomers of aloin and derivatives), with minor glycosides including barbaloin, frangulin, chrysaloin, palmidin A, B and C and the free aglycones.

Senna, Cassia senna L. and C. angustifolia Vahl (Senna) (Sennae fructus, Sennae folium)

Constituents

Leaf. Sennosides A and B (Fig. 14.4), which are based on the aglycones sennidin A and sennidin B; sennosides C and D, which are glycosides of heterodianthrones of aloe-emodin and rhein; palmidin A, rhein anthrone and aloe-emodin glycosides and some free anthraquinones. C. senna usually contains greater amounts of the sennosides.

Fruit. Sennosides A and B and a related glycoside sennoside A1. The sennosides, which are dianthrones, differ in their stereochemistry at C10 and C10′, as well as in their substitution pattern. C. senna usually contains greater amounts of the sennosides.

The structure of sennoside B is given in fig. 14.4. The Eur. Ph. standard is for a glycoside content of not less than 2.5% for the leaf, 3.5% for C. senna fruit and 2.2% for C. angustifolia fruit, calculated as sennoside B. Other secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, tannins and bitter compounds are also present but not defined in the standard. The way in which the plant material is dried has a strong influence on the amount of glycosides and accordingly on the quality of the product (see above).

Inflammatory GI conditions: gastritis and ulcers

Chamomile Matricaria recutita L. (Matricariae flos)

Constituents

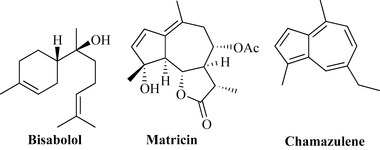

The flower heads are rich in essential oil. Two types of essential oil are recognized: one rich in bisabolol (levomenol) (Fig. 14.5) and the other in bisabolol oxides. Both contain other terpenoid compounds, including guaianolides such as matricin which are only found in the crude drug. The characteristic, dark blue azulenes (e.g. chamazulene; Fig. 14.5) are produced during steam distillation and only found in the essential oil. Flavonoids (up to 6%), especially apigenin and apigenin-7O-glycoside, caffeic acid derivatives and spiro ethers are also present. The components of the essential oil levomenol (α-bisabolol), its oxides, chamazulene, some unusual spiro ethers and the flavonoids (especially apigenin) are all essential for the pharmacological effects of the drug. The minimum amount of essential oil required by the Eur. Ph. is 0.4%.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Anti-inflammatory, spasmolytic, antibacterial and antifungal effects are well established both pharmacologically and clinically (see McKay and Blumberg 2006a). Chamomile is relatively safe, although allergic reactions can occur as with all plants of the family Asteraceae.

Liquorice, Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Liquiritiae radix)

Constituents

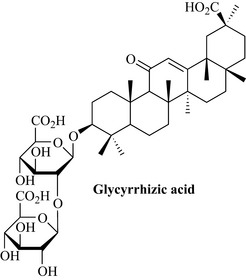

The most important bioactive secondary metabolite is glycyrrhizic acid (also known as glycyrrhizin; Fig. 14.6), a water-soluble pentacyclic triterpene saponin which gives the drug its characteristic sweet taste (it is about 50 times sweeter than sucrose). The genin (glycyrrhetinic acid or glycyrrhetin), on the other hand, is not sweet but very bitter. Liquorice also contains numerous flavonoids (chalcones and isoflavonoids), coumarins and polysaccharides, which contribute to the activity.

Dyspepsia and biliousness

Artichoke, Cynara scolymus L. (Cynarae folium)

Constituents

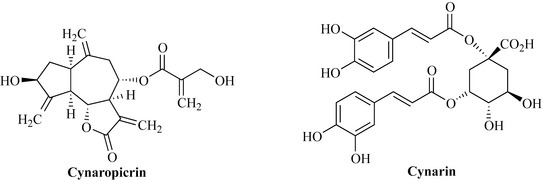

The leaf contains the bitter sesquiterpene lactone cynaropicrin, several flavonoids and derivatives of caffeoylquinic acid, including cynarin (Fig. 14.7).

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Antihepatotoxic effects, cholagogue activity and a reduction of cholesterol and triglyceride levels have been reported, and are now known to be due to inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis. Clinical studies have shown that artichoke leaf extract can improve parameters such as fat intolerance, bloating, flatulence, constipation, abdominal pain and vomiting, and increase bile flow, at a daily mean dose of 1500 mg. For further details, see Bundy et al 2008, and Wider et al 2009. Artichoke extract is also useful in irritable bowel syndrome (Walker et al 2001).

Gentian, Gentiana lutea L. (Gentianae radix)

Constituents

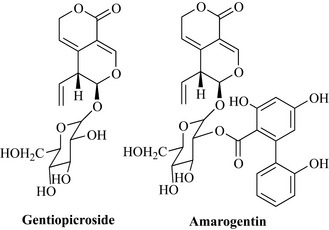

The compounds responsible for the highly bitter taste are monoterpenoid compounds (Fig. 14.8) such as gentiopicroside – a seco-iridoid with a bitter value of 12,000 – and amarogentin – with a bitter value of 58,000,000, which is only present in minute amounts. The normally white inner part of the rootstock turns yellow during fermentation, due to the formation of xanthones, including gentisin. Chemical analysis is carried out following the method of the Eur. Ph., but the ‘bitter value’ test is also useful. This is a simple and useful measure for establishing the quality of bitter-tasting (botanical) drugs. It is the inverse concentration of the dilution of an extract (or a pure compound) which can still be detected as being bitter to testers with normal bitter taste receptors. In the case of gentian, it should at least be 10,000 (i.e. an extract that has been diluted 10,000 times should still leave a bitter taste).

Wormwood, Artemisia absinthium L. (Absinthii herba)

Constituents

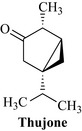

The essential oil contains β-thujone (Fig. 14.9) as the major components, as well as thujyl alcohol, azulenes, bisabolene and others. Sesquiterpene lactones are also present, especially absinthin, anabsinthin, artemetin, artabsinolides A, B, C and D, artemolin and others, and flavonoids. During the process of distillation, the intensively blue chamazulene is formed, which together with the other constituents gives oil of absinth its characteristic green-blue colour. The sesquiterpene lactone absinthin is responsible for the intensive bitter taste, which according to the Eur. Ph. should be at least 10,000 (Deutsches Arzneibuch 15,000) for the crude extract (see ‘Gentian’ for explanation of bitter value). β-Thujone, a monoterpene, is also partly responsible for the bitterness. The essential oil content should be at least 0.2% and the bitter sesquiterpenoids 0.15–0.4%, according to the Eur. Ph. where the methods are described.

Nausea and vomiting

Ginger, Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Zingiberis rhizoma)

Constituents

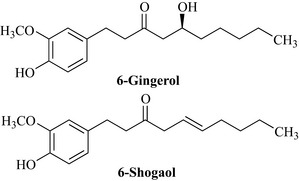

The rhizome contains 1–3% essential oil, the major constituents of which are zingiberene and β-bisabolene. The pungent taste is produced by a mixture of phenolic compounds with carbon side-chains consisting of seven or more carbon atoms, referred to as gingerols, gingerdiols, gingerdiones, dihydrogingerdiones and shogaols (see Fig. 14.10). The shogaols are produced by dehydration and degradation of the gingerols and are formed during drying and extraction. The shogaols are twice as pungent as the gingerols, which accounts for the fact that dried ginger is more pungent than fresh ginger.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Modern uses of ginger are diverse and include as a carminative, anti-emetic, spasmolytic, antiflatulent, antitussive, hepatoprotective, antiplatelet aggregation and hypolipidaemic. Some of these actions are substantiated by pharmacological in vivo or in vitro evidence. Of particular importance is the use in preventing the symptoms of motion sickness and postoperative nausea, as well as vertigo and morning sickness of pregnancy, and there is some clinical evidence for the efficacy of ginger in these conditions (Matthews et al 2010). Ginger consumption has also been reported to have a beneficial effect in alleviating the pain and frequency of migraine headaches, and studies on the action in rheumatic conditions have shown a moderately beneficial effect. Anti-ulcer activity has been described in animals and attributed to the volatile oil, especially the 6-gingesulfonic acid content, and hepatoprotective effects have been noted in cultured hepatocytes, with the gingerols being more potent than the homologous shogaols found in dried ginger. Both groups of compounds are antioxidants and possess free radical scavenging activity. Ginger is well known to produce a warming effect when ingested, and the pungent principles stimulate thermogenic receptors. In addition, zingerone induces catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla (for review, see Ali et al 2008). In Oriental medicine, ginger is so highly regarded that it forms an ingredient of about half of all multi-item prescriptions. A distinction is made between the indications for the fresh rhizome (vomiting, coughs, abdominal distension and pyrexia) and the dried or processed rhizome (abdominal pain, lumbago and diarrhoea). This is probably justifiable since the constituents are present in different proportions in the different preparations. Ginger, both in the fresh and dried form, is generally regarded as safe.

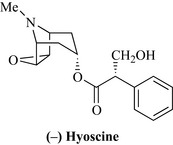

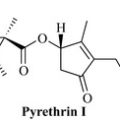

Hyoscine (scopolamine)

The alkaloid hyoscine (Fig. 14.11) is usually isolated from Datura or Scopolia spp., although, as the name suggests, it has originally been found in Hyoscyamus niger. It is a popular remedy for motion sickness, given at an oral dose of 400 μg or, more recently, as a transdermal patch containing 2 mg of the alkaloid, which is delivered through the skin over 24 h. Hyoscine is also used as a premedication, usually in combination with an opiate, to relax the patient and dry up bronchial secretions prior to administration of halothane anaesthetics.

Irritable bowel syndrome, bloating and flatulence

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterized by pain in the left iliac fossa, diarrhoea and/or constipation. Symptoms are usually relieved to some extent by defecation or the passage of wind, and can be treated successfully by the use of bulk laxatives with or without antispasmodic (carminative) drugs. Natural remedies include peppermint oil and other essential oil carminatives, and some of the tropane alkaloids. Atropine has been replaced by hyoscine, in the form of the N-butyl bromide, which, as a quaternary ion, is poorly absorbed from the GI tract and, therefore, has fewer anti-muscarinic side effects. Artichoke extract is also useful in irritable bowel syndrome (Walker et al 2001); see under dyspepsia and biliousness.

Flatulence, which is the passage of excessive wind from the body, is a condition for which phytotherapy offers useful therapeutic approaches. Carminatives are usually taken with food; they produce a warm sensation when ingested and promote postprandial elimination of gas. Plant-based carminatives are usually rich in essential oil, such as the fruits (‘seeds’) of species of the Apiaceae (celery family) and some members of the Lamiaceae (mint family). Many condiments such as cumin and caraway have carminative effects and are used as spices because of their taste and their pharmacological effect. The clinical validity of carminatives is based on long historical observation and is well established. The effect of many of these botanical drugs is due to their spasmolytic action, for which some in vitro evidence exists (Ford et al 2008), but the precise mechanism of action is unclear. It seems likely that not only is the essential oil responsible for the effect, but that the other components (e.g. the flavonoids) also contribute.

Mint leaves and oils: mentha species

Peppermint, Mentha × piperita L. (Menthae piperitae folium)

Constituents

Peppermint oil is derived from the fresh plant by steam distillation and contains approximately 50% (–)-menthol (Fig. 16.4).

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Peppermint is often taken in the form of a tea, which provides a refreshing beverage as well as a mild digestive soothing effect (see McKay and Blumberg 2006b). The oil can be given well-diluted with water or as an emulsion (2%, v/v, dispersed in a suitable vehicle) for treating colic and GI cramps in both adults and children, and in the form of enteric-coated capsules for IBS, where it is released directly into the intestine and bowel. The antispasmodic effect of peppermint oil has been well established using a series of in vitro models, the effect being marked by a decline in the number and amplitude of spontaneous contractions, and due at least in part to Ca2+-antagonistic effects. Peppermint oil has also been shown clinically to enhance gastric emptying. Peppermint water (or emulsion) is generally safe, although must be used with care. A tragic incident with peppermint water caused the death of a young baby, although the toxicity was due to the excipient rather than to the peppermint oil (by adding concentrated chloroform water rather than the diluted form, two pharmacists inadvertently produced a lethal medication).

Umbelliferous fruits

Caraway, Carum carvi L. (Carvi fructus)

Caraway is the fruit of a mountain herb common in many regions of Europe and Asia.

Constituents

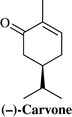

The essential oil (3–7%) consists mainly of (+)-Carvone and (+)-limonene, accounting for 45–65% and 30–40%, respectively, of the total oil. Carvone (Fig. 14.12) is considered to be the main component responsible for the spasmolytic action.

Fennel, Foeniculum vulgare Miller (Foeniculi fructus)

Constituents

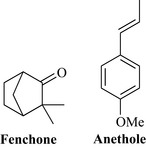

All of the aerial parts of fennel are rich in essential oil, with bitter fennel fruit containing 2–6%, mostly trans-anethole (> 60% of the oil) and fenchone (> 15%) (Fig. 14.13), and sweet fennel containing 1.5–3%, composed of trans-anethole (80–90%) but with very little fenchone (< 1%). Fatty oil and protein are also found in fennel fruit.

Liver disease

Liver damage, cirrhosis and poisoning should only be treated under medical supervision. There is, however, a useful phytomedicine derived from the milk thistle, Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. (Asteraceae), in the form of an extract known as silymarin. Other herbs, as shown below, are widely used for liver disease, although with less clinical evidence in support. Herbs used for ‘biliousness’ (see section on Dyspepsia and Biliousness) are also used in mild liver disease.

Andrographis, Andrographis paniculata Nees (Andrographis herba)

Andrographis is widely used in many Asian systems of medicine to treat jaundice and liver disorders. There are few clinical studies available to support these uses, although numerous in vitro experiments have shown it has liver protective effects against a variety of hepatotoxins. 14-deoxyandrographolide, a constituent, desensitizes hepatocytes to TNF-alpha-induced signalling of apoptosis (Roy et al 2010). It appears to be well-tolerated but caution should be exercised when given in conjunction with anti-thrombotic drugs. In the West, it is more often used as an immune stimulant (see Chapter 16, Respiratory System, for more detail, including constituents).

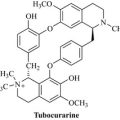

Berberis species and other berberine-containing drugs

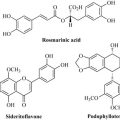

Berberine (Fig. 14.14) is contained in Berberis species, for example B. vulgaris L., B. aristata DC, in Blood root, Sanguinaria canadensis L., Goldenseal, Hydrastis canadensis L., Gold Thread, Coptis chinensis Franch, and Greater Celandine, Chelidonium majus L.

Berberine has antibacterial and amoebicidal properties and is used either in the form of the pure compound or as a component of plant extracts, to treat dysentery and liver disease (Imanshahidi and Hosseinzadeh 2008). Care should be taken when given together with anticancer drugs and with ciclosporin, since theoretical drug interactions have been described for these combinations, and berberine is known to be a substrate of P-glycoprotein and to affect expression of cytochrome P(CYP) 450 enzymes 3A4 and others.

Milk Thistle, Silybum marianum (Silybi Marianae Fructus)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

In many parts of Europe, silymarin is used extensively for liver disease and jaundice. It has been shown to exert an antihepatotoxic effect in animals against a variety of poisons, particularly those of the death cap mushroom Amanita phalloides. This fungus contains some of the most potent liver toxins known (the amatoxins and the phallotoxins), both of which cause fatal haemorrhagic necrosis of the liver. Silymarin has been used at doses of 420 mg daily to treat patients with chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis; it is also partially active against hepatitis B virus, is hypolipidaemic and lowers fat deposits in the liver in animals. This extract can be used not only for serious liver disease, but also for general biliousness and other digestive disorders (see Saller et al 2008).

Turmeric, Curcuma domestica Val. (Curcumae domesticae rhizoma)

Turmeric is used in Asian medicine to treat liver disorders and well as inflammatory conditions. For details regarding the drug and its constituents, see Chapter 21 (Musculoskeletal system). Related species include Javanese turmeric (Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb., Eur. Ph.), which is mostly used for dyspepsia and other gastrointestinal problems. Turmeric and the curcuminoids are hepatoprotective against liver damage induced by various toxins, including paracetamol (acetaminophen), aflatoxin and cyclophosphamide; they protect against stomach ulcers in rats, and have antispasmodic effects. Turmeric is also hypoglycaemic in animals, and hypocholesterolaemic effects have been observed both in animal and human clinical studies, although clinical studies for liver disease are lacking. In addition, turmeric is antibacterial and antiprotozoal in vitro. Turmeric is well tolerated but the bioavailability is poor and daily doses of at least 2g are normally used. For reviews see, Rivera-Espinoza and Muriel (2009) and Epstein et al (2010).

Ali B.H., Blunden G., Tanira M.O., Nemmar A. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): a review of recent research. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2008;46:409-420.

Bundy R., Walker A.F., Middleton R.W., Wallis C., Simpson H.C. Artichoke leaf extract (Cynara scolymus) reduces plasma cholesterol in otherwise healthy hypercholesterolemic adults: a randomized, double blind placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:668-675.

Epstein J., Sanderson I.R., Macdonald T.T. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent: the evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies. Br. J. Nutr.. 2010;103:1545-1557.

Ford A.C., Talley N.J., Spiegel B.M., et al. Effect of fibre, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a2313.

Imanshahidi M., Hosseinzadeh H. Pharmacological and therapeutic effects of Berberis vulgaris and its active constituent, berberine. Phytother. Res.. 2008;22:999-1012.

Matthews A., Dowswell T., Haas D.M., Doyle M., O’Mathúna D.P. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010. 2010 Sep 8:CD007575

McKay D.L., Blumberg J.B. A review of the bioactivity and potential health benefits of chamomile tea (Matricaria recutita L.). Phytother. Res.. 2006;20:519-530.

McKay D.L., Blumberg J.B. A review of the bioactivity and potential health benefits of peppermint tea (Mentha piperita L.). Phytother. Res.. 2006;20:619-633.

Palumbo E.A. Phytochemicals from traditional medicinal plants used in the treatment of diarrhoea: modes of action and effects on intestinal function. Phytother. Res.. 2006;20:717-724.

Panossian A., Wikman G. Pharmacology of Schisandra chinensis Bail.: an overview of Russian research and uses in medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2008;118:183-212.

Rivera-Espinoza Y., Muriel P. Pharmacological actions of curcumin in liver diseases or damage. Liver Int.. 2009;29:1457-1466.

Roy D.N., Mandal S., Sen G., Mukhopadhyay S., Biswas T. 14-Deoxyandrographolide desensitizes hepatocytes to tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis through calcium-dependent tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A release via the NO/cGMP pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol.. 2010;160:1823-1843.

Saller R., Brignoli R., Melzer J., Meier R. An updated systematic review with meta-analysis for the clinical evidence of silymarin. Forsch. Komplementmed.. 2008;15:9-20.

Walker A.F., Middleton R.W., Petrowicz O. Artichoke leaf extract reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a post-marketing surveillance study. Phytother. Res.. 2001;15:58.

Wider B., Pittler M.H., Thompson-Coon J., Ernst E. Artichoke leaf extract for treating hypercholesterolaemia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7(4), 2009. Oct CD003335