Chapter 7 The Forearm, Wrist, and Hand

The importance of the wrist and hand is evidenced by the fact that the rest of the upper extremity functions primarily to place the hand in a position where it can operate most effectively. Treatment of the wide variety of disorders that occur in the hand requires an understanding of its complicated anatomy and functional physiology.

Anatomy

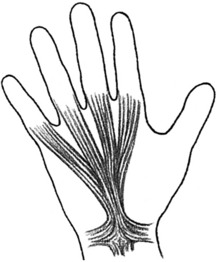

SKIN, FASCIA, AND NAIL

The skin on the dorsum of the hand is loose and overlies a subcutaneous space through which pass many veins and most of the lymph vessels of the hand. This abundance of lymph vessels accounts for the dorsal lymphedema that commonly occurs secondary to infection in the palm or fingers. The palmar skin, however, is firmly attached to the underlying palmar aponeurosis, which is continuous with the palmaris longus tendon (Fig. 7-1). This thick fascia sends extensions into the fingers and protects the important deeper structures of the hand. It may become nodular and shortened in Dupuytren’s contracture.

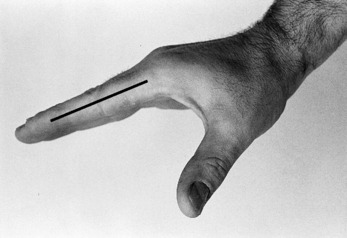

BLOOD SUPPLY

Most of the blood supply to the hand enters on the palmar aspect through the radial and ulnar arteries. Each of these arteries terminates in a superficial and a deep branch. The superficial branches join to form the superficial palmar arch, which is located at the level of the base of the first web space. The deep palmar arch, located 1 cm proximal to the superficial arch, is formed by the junction of the deep branches. The arches are named for their position relative to the flexor tendons. Many branches and anastomoses from these arches provide the blood supply to the fingers and hand. In the fingers, digital vessels (and nerves) lie just ventral to the flexor skin crease of the interphalangeal joints (Fig. 7-2).

MUSCLES OF THE HAND

Motions of the wrist and fingers are controlled by groups of muscles that are classified as either intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic muscles arise within the hand and are responsible for the delicate movements of the fingers. Thenar refers to intrinsic muscles of the thumb. Hypothenar refers to those on the ulnar side of the hand. Extrinsic muscles are those that take origin within the forearm.

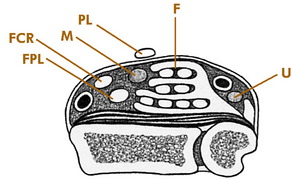

EXTRINSIC MUSCLES

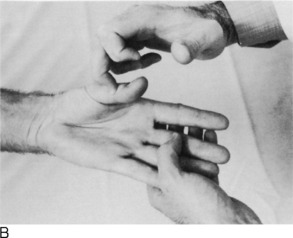

Nine finger flexors and the median nerve pass into the hand through the carpal tunnel beneath the transverse carpal ligament (Fig. 7-3). Five deep flexors pass to the distal phalanx of each finger and thumb, and four superficial flexors pass to the middle phalanx of each finger. Each of these finger flexors can be tested individually (Fig. 7-4).

The extensor tendons pass dorsally over each finger and thumb and insert into the phalanges. They extend the proximal phalanges and assist the intrinsic muscles in interphalangeal joint extension. The thumb extensors are easily palpated at the anatomic “snuffbox.”

NERVE SUPPLY

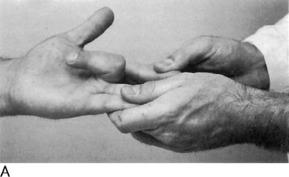

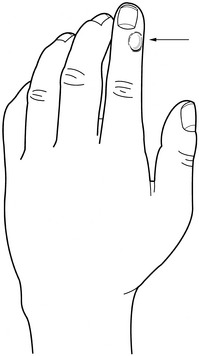

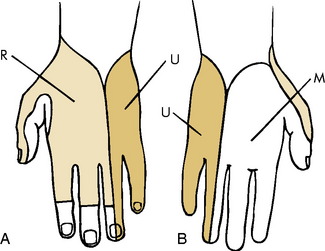

The ulnar nerve provides the motor supply to all of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, except the two radial lumbricals and the thenar muscles. It also provides sensation to the entire ulnar 1½ fingers (Fig. 7-5). Its function is easily evaluated by testing finger abduction and palpating the belly of the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Fig. 7-6).

Fig. 7-5 Dorsal (A) and palmar (B) sensation of the hand. R, Radial nerve; U, ulnar nerve; M, median nerve.

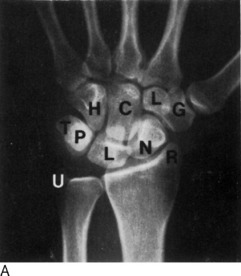

Roentgenographic Anatomy

The 27 bones of the hand are visualized by anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique roentgenograms when appropriate (Fig. 7-7).

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Sometimes, a combination of neck and hand pain can develop, especially in patients who suffer from degenerative cervical disc disease. This is termed the “double-crush syndrome” lesion and results from nerve compression at two separate levels, the neck and the wrist. This suggests that proximal compression may decrease the ability of the nerve to tolerate a second, more distal compression.

CLINICAL FEATURES

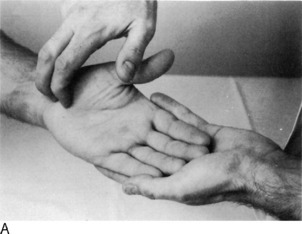

The onset is usually spontaneous, with gradually increasing pain and tingling in the hand. Nocturnal pain is common and is frequently the reason the patient seeks medical attention. This may be caused by a slight increase in swelling at the wrist with inactivity or perhaps as a result of wrist flexion at night. Pain may radiate proximally into the forearm and even as high as the shoulder. Numbness and tingling occur along the median nerve distribution, but the sensory impairment rarely involves all 3½ fingers supplied by the median nerve. Often, only the long and index fingers are involved. A sense of weakness and clumsiness in the use of the hand is common. All of these symptoms may be precipitated by various manual activities such as typing or painting. They frequently subside after shaking and moving the hand or allowing it to hang downward. The patient often describes “poor circulation” and “stiffness,” but the hand is usually warm, and the motion is full. These latter symptoms are probably caused by the numbness. Physical examination may reveal some sensory disturbance along the median nerve. Tinel’s sign and Phalen’s maneuver are often positive (Fig. 7-8). Atrophy of the thenar muscles is seen in cases of long-standing duration.

Roentgenograms of the wrist are helpful in ruling out local bony abnormality. Nerve conduction studies may be of benefit but are frequently unnecessary in classic cases. Delayed electrical conduction across the wrist is usually present. Electromyography is generally not required. Some error may exist in electrodiagnostic testing, and it should not be the sole guide to diagnosis and treatment.

TREATMENT

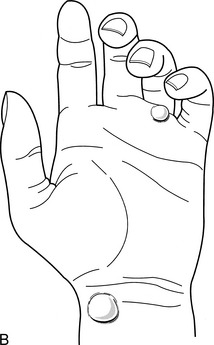

Ganglion

Ganglions are soft tissue lesions that are commonly found in the extremities. They are always found adjacent to a joint or tendon sheath. The cause is unknown, but myxoid degeneration of connective tissue and repetitive trauma with chronic irritation are possible causes. The cyst contains a very thick mucinous material and usually has a stalk that can be traced to a tendon sheath or joint.

CLINICAL FEATURES

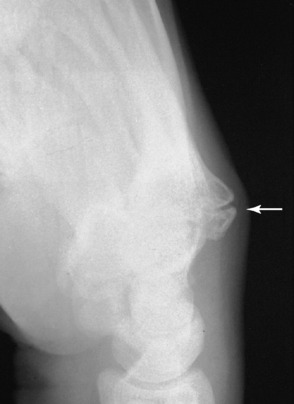

A history of trauma is rarely elicited. Local pain and a feeling of weakness may be noted, but many are asymptomatic. The mass may change in size, with this change often being related to the level of activity of the patient. Ganglia are most common on the dorsum of the wrist. They are more prominent with the wrist flexed and are usually freely movable (Fig. 7-10).

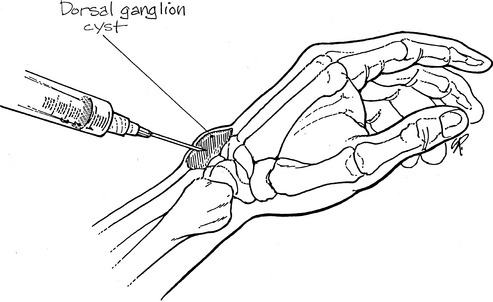

TREATMENT

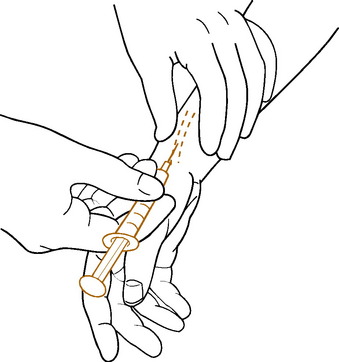

Simple observation is recommended if symptoms are minimal. Ganglia resolve spontaneously in approximately 40% to 50% of cases. A cure may be effected by aspirating or puncturing the cyst in multiple areas and injecting it with a steroid compound (Fig. 7-11). A large (18-gauge) needle is required to aspirate the thick gel. A compression pad is then applied over the lesion for 48 to 72 hours. Recurrence is common.

If symptoms persist, excision of the cyst may be indicated. The recurrence rate is 5% to 10%.

Degenerative Arthritis

Although osteoarthritis of the wrist and hand is much less common than in the lower extremities, it is sometimes more disabling. In the hand, it is 10 times more common in the females than males, and the most common area of involvement is the trapeziometacarpal or “base joint” of the thumb (Fig. 7-12). Involvement at the base joint of the thumb is particularly bothersome because of the tremendous mobility required by this joint in daily use. Sometimes deformity of this joint even develops the appearance of a “mass” because of osteophyte formation, swelling, and subluxation. The arthritis is considered “primary” in most cases but can also develop secondary to fractures and other joint injuries. When the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints become involved with arthritis, persistent nodular swellings called Heberden’s nodes may develop. Similar lesions at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints are termed Bouchard’s nodes. Occasionally, mucous cysts also develop at these interphalangeal (IP) joints.

TREATMENT

Treatment is similar to arthritis elsewhere. Anti-inflammatory medication, intermittent splinting, moist heat, and occasional local cortisone injections are usually successful in temporarily relieving symptoms (Fig. 7-13). Cystic lesions may be aspirated but should not be drained open. Patients with refractory symptoms should be referred. Arthroplasty and arthrodesis are occasionally necessary to control pain.

Dupuytren’s Contracture

CLINICAL FEATURES

The disorder is usually painless. Age of onset is usually between 40 and 60 years. Deformity and interference with the use of the hand by the flexed, contracted fingers are the most common complaints. The process usually begins on the ulnar side of the hand, often starting at the ring finger. An isolated nodule may appear in this area that eventually hardens and later disappears. The overlying skin becomes adherent to the fascia, and a strong fibrous cord develops that extends into the finger (Fig. 7-14). In the later stages of the disorder, the cord may begin to contract and pull the finger into flexion. Multiple fingers may be affected.

Stenosing Tenosynovitis

This common condition of unknown origin may develop from overuse or direct trauma. The resultant inflammation and irritation hinder the normal gliding motion of the tendon. Most cases are primary (idiopathic), although the condition can develop in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Several distinct syndromes can be described, depending on the site of involvement.

DE QUERVAIN’S DISEASE

Tenosynovitis frequently occurs in the first dorsal extensor compartment of the wrist (Fig. 7-15). The extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus occupy this compartment and are involved where they cross over the radial styloid.

TREATMENT

Treatment in mild cases includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), immobilization, avoidance of the offending activity, and steroid injections into the tendon sheath (Fig 7-16). Braces or other immobilizing devices should always include the thumb as well as the wrist. Moist heat is applied as necessary for comfort.

TRIGGER FINGER AND THUMB

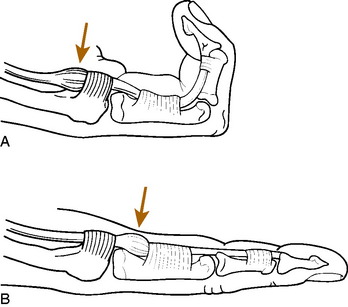

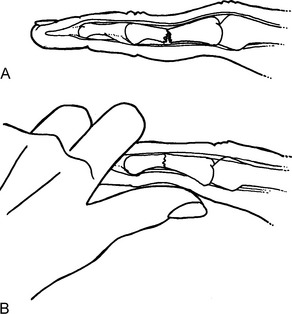

If swelling of the flexor tendon and sheath occurs, passage of the tendon through the constricted sheath may become difficult (Fig. 7-17). This may result in snapping or “triggering” of the affected finger at the MP joint as the swollen, nodular tendon passes through the constricted sheath. The symptoms are frequently worse after rest and improve with active use of the finger. The effect of the triggering itself is transmitted distally to the DIP joint. The finger may even lock completely in either flexion or extension. If the digit locks in flexion, manipulation may be required to extend the finger, a maneuver usually accompanied by a palpable snap. In mild cases, however, the triggering effect may be subtle. Examination usually reveals tenderness and a firm swelling at the proximal flexor pulley. If multiple fingers are involved, rheumatoid disease should be suspected. A congenital form is occasionally seen in the thumb of children.

Repetitive Motion Syndrome

Some reasons for the controversial nature of the disorder are as follows:

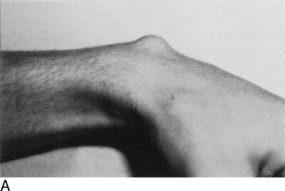

Ulnar Nerve Entrapment (Cubital Tunnel Syndrome)

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common nerve compression in the upper extremity. It may occur from several causes, but the most common is chronic trauma to the nerve where it passes behind the elbow. The nerve is most superficial at this location and is easily subjected to external pressure. Leaning on the elbow or repeated flexion and extension may also be factors in its onset. Elbow synovitis with synovial enlargement and muscular hypertrophy may also cause localized pressure in the tunnel. A cubitus valgus deformity at the elbow secondary to a growth plate fracture or infection may also cause paralysis (“tardy ulnar palsy”) by progressive stretching of the nerve in its groove behind the elbow (Fig. 7-18). The nerve may even sublux in and out of its groove on occasion, thereby giving rise to symptoms.

Clinical Features

Minimal pressure against the elbow may lead to paresthesias and numbness along the distribution of the ulnar nerve in the forearm and hand, mainly the small finger (Table 7-1). Tinel’s sign is often positive. The elbow flexion test may be abnormal. This test is performed by having the patient flex the elbow for 30 to 60 seconds with the wrist extended. This maneuver increases the volume and pressure in the cubital tunnel and may reproduce symptoms. The test is not diagnostic, however, because it may be positive in asymptomatic individuals.

Table 7-1 Differential Diagnosis of Common Causes of Forearm and Hand Pain*

| Disorder | Findings Present | Findings Absent |

|---|---|---|

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Painful paresthesias along portions of median nerve (i.e., palm side of hand). Index and long often only fingers involved. May have night pain in long-standing cases. Pain may radiate as high as shoulder. Tinel’s sign may be positive at wrist. | Pain not worsened by resisted motion or stretching. No symptoms on dorsum of hand. Full range of motion. |

| Tenosynovitis | Pain and tenderness usually well localized to site of involvement. Pain may be reproduced by passive stretch or resistance against movement of affected tendon. May be local swelling. | No paresthesias. Full range of motion. No night pain. |

| Tennis elbow (most common lateral) | Pain may radiate from elbow to forearm and hand. Localized tenderness at epicondyle. Pain aggravated by resisted dorsiflexion of wrist (if lateral). Pain with gripping activities. | Full range of motion, no paresthesias or night pain. |

| Osteoarthritis | Local tenderness, sometimes with swelling of affected joint. Pain with motion. Decreased motion. | No paresthesias. Tinel’s sign negative. |

| Cubital tunnel syndrome | Painful paresthesias along ulnar nerve distribution in forearm and hand. Tinel’s sign may be positive behind medial epicondyle. | Full range of motion. Pain not worsened by resisted motion. No night pain.* |

* Notes: Treatment and workup: 1. NSAID, moist heat, splint, and modification of activities as indicated for 2 to 4 weeks. 2. Roentgenogram, inject (if appropriate), change NSAID for 2 to 4 weeks. 3. Nerve conduction studies, referral as indicated.

In contrast to ulnar tunnel syndrome at the wrist, symptoms are also present on the dorsum of the hand and ulnar forearm. More severe involvement leads to progressive forearm, hypothenar, and intrinsic motor weakness (weak fanning of the fingers) and atrophy, especially the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Fig 7-19). If the nerve subluxes, the subluxation is usually palpable with elbow flexion and extension. Nerve conduction studies usually reveal delayed conduction at the elbow.

Kienbock’s Disease

Avascular necrosis of the carpal lunate bone is an uncommon disorder that may follow an injury. The cause is unknown, but the condition is considered to represent a circulatory disturbance to the bone. An abnormally short ulna (negative ulnar variance) may be a risk factor. A similar involvement of the navicular is termed Preiser’s disease.

CLINICAL FEATURES

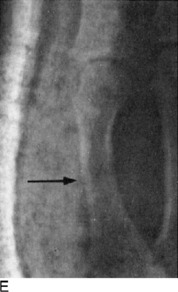

The disorder is most common in men between the ages of 20 and 40. Although it is uncertain if trauma plays a role, a history is sometimes obtained of a single major injury. Multiple minor injuries, such as those that occur with certain manual occupations, may also lead to symptoms. Chronic pain, tenderness, swelling, and restriction of wrist motion (especially dorsiflexion) are common. The pain may be aggravated by passive dorsiflexion of the long finger in Kienbock’s disease or the index finger in Preiser’s disease. The initial roentgenogram findings are usually normal, but eventually the affected bone becomes abnormally dense and white (Fig. 7-20). Later, fragmentation and collapse occur. The end result is frequently degenerative arthritis throughout the wrist.

Soft Tissue Injuries

FINGERTIP INJURIES

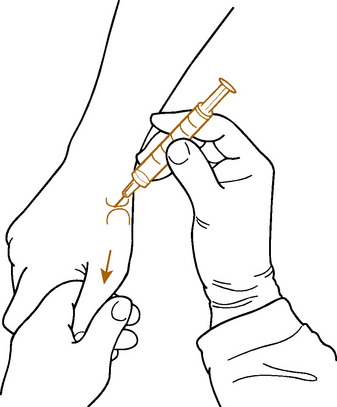

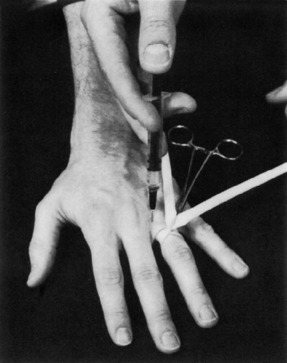

A variety of fingertip injuries are encountered in daily practice. By definition, these are injuries that occur distal to the DIP joint. Bone, skin, and nail may all be involved in varying degrees. Examination and treatment of most of these injuries may be performed under a metacarpal block using 1% lidocaine anesthesia. The anesthesia is instilled into the web space rather than the digit to prevent pressure on the digital vessels (Fig. 7-21). Epinephrine should not be used. A small Penrose drain applied to the base of the finger makes a satisfactory tourniquet. Some general principles in the treatment of these injuries should be followed:

EPITHELIALIZATION

Many minor soft tissue amputations of the pulp without bone loss that are less than 1 cm square can be treated by thorough cleansing, debridement, and healing by secondary intention, especially if the amputation is transverse or dorsal oblique (Fig. 7-22). (Even some amputations with minimal exposed bone may be treated in the same fashion if the protruding bone is shortened first.) Dressings are changed in 2 days and then daily, using tube gauze and petroleum jelly. Recovery is usually rapid (2 to 3 weeks). Significant volar pulp loss may be a contraindication to this method of care, where a padded flap graft might be more appropriate. If there is any question, it is always acceptable to temporize on fingertip injuries. The wound may be cleaned and dressed and referred for further care at a later date.

FREE GRAFTS

Free grafts are usually split thickness or full thickness. The thinner grafts tend to “take” better than do thicker grafts but do not afford the protection of a full-thickness graft. Although they may heal over bone or tendon, secondary revisions are often necessary. Their use should be limited to dorsal wounds or those without exposure of bone or tendon. These thin grafts may be obtained from a number of areas. The donor area often ends up being unsightly after healing, however, and should be chosen carefully. The thigh or lateral aspect of the buttock is a satisfactory donor site. Full-thickness grafts provide better protection for the volar aspect of the finger but have the same limitations as split-thickness skin grafts when used over bone and tendon. They are less sensitive and may be used on volar injuries. The flexor creases of the wrist and elbow are excellent donor sites. The donor wound is easily closed without undue tension in these areas. The graft should include no subcutaneous tissue. As with all grafting procedures, it is wise to plan backward and be certain that the graft will completely cover the area of the wound. If the patient brings in the amputated fingertip, it may be used as a full-thickness graft if it is in good condition. All fat must be removed before application. In children younger than 5 years of age, defatting the tip is not necessary. As healing progresses, full-thickness grafts may become dark after a few days. This should not be a cause for alarm, because the deeper portion is usually viable, despite the appearance of the more superficial layers.

CRUSH INJURIES

Crush injuries are the result of direct violence to the tip of the finger. A painful subungual hematoma or fracture of the distal phalanx may occur (Fig. 7-23). The treatment of these injuries is directed at the soft tissues. After proper surgical site preparation and cleansing, an isolated painful hematoma may be drained before it has coagulated by gently drilling a hole into the nail with a No. 11 blade or an 18-gauge needle spun between the fingertips. A heated paper clip may also be used. When the hematoma involves 50% of the plate, nail bed laceration should be suspected. In these cases, the nail may need to be removed to repair the bed. The nail should be cleaned and replaced after the bed has been sutured. The nail may be perforated to allow drainage, but do not place the hole over the site of the repair.

EXTENSOR TENDON INJURIES

Lacerations in the extensor complex must be repaired accurately, and there should be no hesitation to extend the wound proximally or distally to properly visualize the ends of the tendon. Direct end-to-end repair using nonabsorbable suture such as nylon is desirable (Fig. 7-24). The finger and wrist are splinted in extension to remove tension from the suture line. Immobilization is maintained for approximately 4 weeks.

FLEXOR TENDON INJURIES

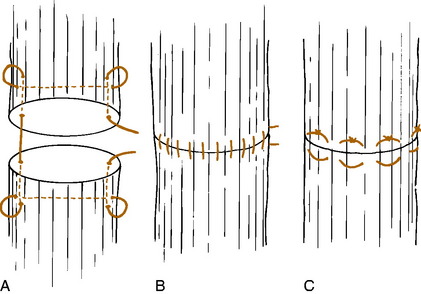

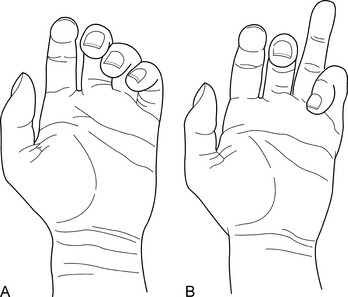

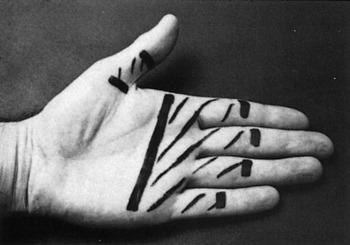

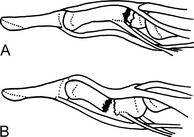

Flexor tendon injuries are diagnosed by history and examination. Partial or complete loss of finger flexion is accompanied by a typical posture of the finger (Fig. 7-25). There are often associated digital nerve injuries. Repair of flexor tendon injuries is a complex problem that should be undertaken only in the operating room by an experienced surgeon. Primary repair of these injuries is indicated when the laceration occurs distal to the sublimis insertion or proximal to the distal palmar crease. Primary tendon repair between these two points, in so-called no-man’s land, is frequently unrewarding because adhesions are likely to form between the lacerated tendon ends and the flexor sheath and pulleys (Fig. 7-26). In selected cases of sharp wounds, primary tendon repair may be undertaken in this area. Otherwise, simple closure of the skin laceration followed by secondary tendon grafting in 6 to 8 weeks is often preferable.

Hand Infections

HUMAN BITES

These are common injuries that are often mistaken for innocuous lacerations. Serious complications and dis ability frequently result, however, usually from the inoculation of virulent oral bacteria into the wound. A variety of organisms may be involved, but the most common are mixed anaerobes and aerobes, streptococci, and Staphylococcus aureus. More than half of hospital admissions for hand infection are caused by human bites.

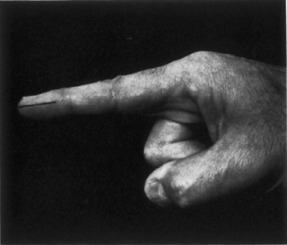

FELON

A felon is an infection of the closed space of the pad of the distal phalanx (Fig. 7-27). It occurs secondary to a local puncture wound and is characterized by rapidly increasing pressure and pain. The entire pulp of the fingertip is swollen, tense, and reddened. The swelling typically does not cross the distal flexion crease. Osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx and extension of the infection into the flexor sheath or adjacent joint may result. S. aureus is the most common offending organism. Early incision and drainage are indicated. A short 24-hour trial of conservative treatment with antibiotics and hot packs may be attempted, but if symptoms do not rapidly diminish, early drainage is advisable. A metacarpal block is adequate anesthesia. A tourniquet is applied to the base of the finger, and a direct incision is made into the point of maximum tenderness and swelling on the volar aspect of the pulp. The incision does not have to be any longer than 5 to 10 mm. If no specific “point” can be detected, a straight lateral incision, which may be extended around the tip of the finger, is made and extended down to bone (Fig. 7-28). The “fish-mouth” incision should not be used. A pack should be inserted that is removed in 2 days. Routine care of the wound after drainage includes dressing changes every 2 to 3 days and maintenance of antibiotic therapy. The wound is allowed to heal by secondary intention and usually heals within 2 weeks.

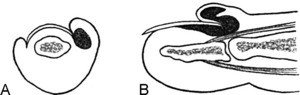

PARONYCHIA

Paronychia is an infection of the distal phalanx that occurs along the edge of the nail. The organism, usually Staphylococcus, is often introduced by biting the nail or by a rough manicure (anything that breaks the seal between the nail plate and proximal nailfold). Local signs of infection, such as redness, swelling, and tenderness, are invariably present (Fig. 7-29).

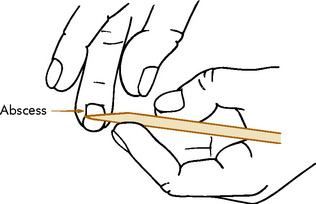

Acute paronychia usually requires drainage, although oral antibiotics and local care occasionally result in a cure in 3 to 5 days. Once the pus has localized, incision and drainage are indicated. This is easily accomplished by passing a scalpel between the nail and the adjacent eponychium under local anesthesia (Fig. 7-30). If the infection has penetrated under the nail, a small portion of the lateral nail may have to be excised. Incision and drainage through the eponychium should be avoided.

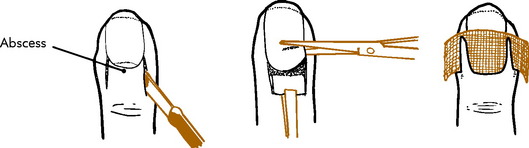

Once the infection spreads under the nail, a subungual abscess results. In this case, drainage is only effective if the proximal part of the nail is excised (Fig. 7-31). The nail usually regrows. Chronic paronychia is treated in a similar manner, although the organism involved is often Candida albicans, which may respond to topical antifungal agents. Dermatology referral may be needed in refractory chronic cases.

TENDON SHEATH INFECTIONS

Infection may occur inside a flexor tendon sheath from extension of a felon or directly from a puncture wound. The rapid increase in pressure because of the accumulation of pus may obliterate the blood supply to the tendon and result in necrosis and complete loss of function of the tendon. The infection may also spread through the rest of the hand. Early diagnosis and treatment are therefore important.

Fractures of the Forearm

Fractures in Adults

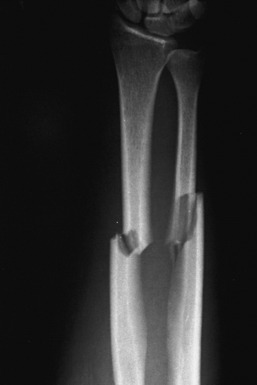

Fractures that occur through both bones of the forearm in adults are usually shortened and displaced (Fig. 7-32). Accurate reduction of these injuries by closed methods is difficult, and there is a strong tendency for these unstable fractures to angulate after swelling subsides, in spite of a good reduction and cast immobilization. Strong muscular forces acting across the fracture fragments predispose to this loss of correction. Consequently, there is a high rate of nonunion. For these reasons, displaced fractures of both bones of the forearm in the adult are often treated by primary open reduction and internal fixation. Closed treatment may be attempted, but if it is unsuccessful the first time, operative intervention is usually indicated. The length of immobilization is shorter with surgery, and there is a more rapid return of function. Undisplaced fractures of both bones are treated with a long arm cast for 8 to 12 weeks. Isolated fractures of either the radius or the ulna are treated in a similar manner. If enough angulation is present to interfere with rotation, closed reduction is attempted. If it is unsuccessful, open reduction and internal fixation are indicated. Undisplaced fractures are treated with a long arm cast for 8 to 12 weeks or until healing is complete.

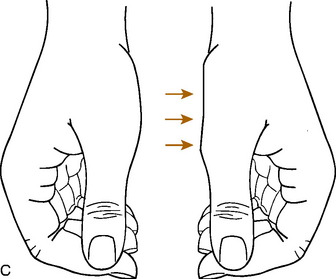

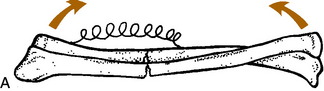

FRACTURES IN CHILDREN

Fractures in children differ from those in adults in that surgery is rarely necessary. Reduction is usually possible by manipulation with the patient under light anesthesia. Angulated fractures are reduced by traction and countertraction, with manual correction of the angulation. It is often necessary to break the opposite cortex of the greenstick fracture to prevent reangulation from occurring in the cast (Fig. 7-33). Displaced fractures are treated by reduction with traction and countertraction (Fig. 7-34). Slight “bayonet” apposition is acceptable in young children if the alignment is satisfactory because subsequent remodeling of growth corrects minor deformities. Children are examined at weekly intervals for 3 weeks to determine whether any reangulation of the fracture is occurring after the swelling subsides. If angulation does recur before 2 weeks pass, it can usually be corrected manually. However, if more than 2 weeks has passed, the healing is so rapid in children that the angulation may be permanent. The cast is worn for 7 to 8 weeks.

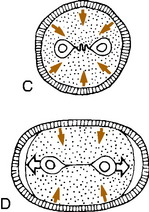

TRAUMATIC BOWING OF THE FOREARM

This is an unusual clinical entity in which “plastic deformation” of the radius and/or ulna occurs in the absence of typical clinical and roentgenographic findings for fracture (Fig. 7-35). The usual cause is a fall on the outstretched hand. There may be a fracture of one bone and bowing of the other or, less commonly, bowing of both bones. Management of these injuries is controversial. Persistent angulation could limit pronation and supination, although young children (younger than 5 years) will undergo bone remodeling and probably do not need reduction. An angulated fracture of one bone is also difficult to reduce until the bowing of the other bone is corrected. In older children, the angulation should be corrected. The reduction may require significant force, and general anesthesia is usually needed. These patients should always be referred for an orthopedic consultation.

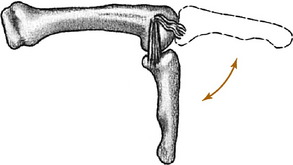

GALEAZZI FRACTURE–DISLOCATION

This injury is a fracture of the shaft of the radius with a dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint (Fig. 7-36). It is rare in children. The disorder is sometimes called the reverse Monteggia fracture. Usually, the radius is fractured in its distal third, and the radioulnar disruption is often missed. Surgery is usually required for repair.

Fractures of the Wrist

COLLES’ FRACTURE

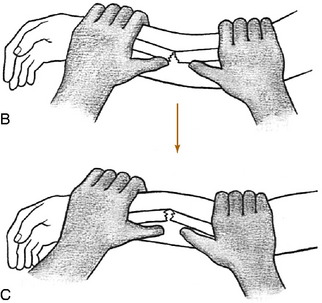

Colles’ fracture is the most common injury of the wrist. It usually results from a fall on an outstretched hand. The force of the fall fractures the distal portion of the radius and displaces it into the typical “silver-fork” position. In addition to the dorsal angulation, there is shortening and radial deviation of the distal fragment (Fig. 7-37). There is usually an associated injury to the ulnar styloid or ulnar collateral ligament of the wrist. The fracture can usually be reduced under local anesthesia if reduction is performed within a few hours. If more time passes, a general anesthetic may be necessary, because the local anesthetic may not diffuse through the clotted hematoma after several hours have passed. The tip of the ulna should also be injected.

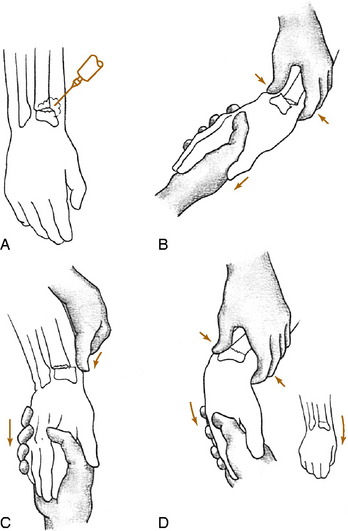

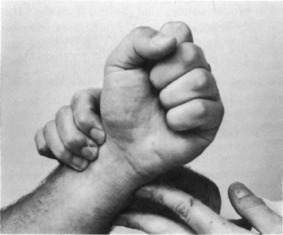

With the assistant grasping the forearm for countertraction, the surgeon grasps the hand of the affected wrist (Fig. 7-38). The thumb of the surgeon’s other hand is placed over the distal fragment, and the wrist is hyperextended to break up any impaction. Traction and countertraction are then applied, and by using the thumb for pressure on the distal fragment, the rotation is corrected, and the dorsal cortex of the distal fragment is forced onto the dorsal cortex of the proximal fragment (see Chapter 2). Ulnar and volar pressure over the distal fragment will then correct the radial and dorsal angulation. The radial styloid is palpated to determine whether the length has been restored. With the assistant maintaining volar and ulnar tension on the hand, a well-molded cast is applied with the wrist slightly pronated. The cast is well molded over the dorsal and radial aspects of the distal fragments and the volar aspect of the proximal fragment to keep the dorsal soft tissue tight. A short arm cast is usually sufficient. Excessive volar flexion of the wrist should be avoided and is unnecessary if the cast is properly applied and molded. Excessive flexion of the wrist may cause median nerve compression. The base of the thumb may be included to the IP joint to help prevent radial collapse.

SMITH’S FRACTURE

This fracture has often been called the reverse Colles’ fracture (Fig. 7-39). One form of this fracture may be considered as such. The type that does not involve the articular surface may be treated by traction, manipulation, and casting in supination. Treatment in supination is important. “Cocking up” the wrist (the reverse of the Colles’ treatment) will frequently not hold the reduction. One type of Smith’s fracture has an articular component that results in volar subluxation of the carpal bones. This injury often requires open reduction with internal fixation for satisfactory results.

FRACTURE OF THE DISTAL RADIUS IN CHILDREN

In children and adolescents, a fracture may occur through the distal radial epiphysis. If it is displaced or angulated over 15 to 20 degrees, it is reduced in the same manner as Colles’ fracture and immobilized in a well molded cast for 5 weeks. Reontgenograms should always be repeated at 7 to 10 days to be certain that loss of position has not occurred. If the fracture is undisplaced, the diagnosis may be difficult. It should be kept in mind, however, that sprains of the wrist are very rare in children because the epiphyseal plate is weaker than the surrounding ligamentous structures, and trauma will usually produce an epiphyseal fracture rather than a ligamentous sprain. Clinical tenderness over the epiphysis is highly suggestive of a fracture, and a short arm cast should be applied to these injuries for 2 weeks even though the roentgenographic findings may be normal. If a healing callus is present at the end of 2 weeks, the cast is continued for an additional 2 weeks. If no callus is present, the cast is removed, and the “sprain” has had excellent treatment. Fractures of the distal portion of the radius also occur in children approximately 2.5 cm above the wrist joint. They are treated in the same manner as Colles’ fracture. Undisplaced or so-called torus fractures also occur in this area (Fig. 7-40). No displacement occurs with this injury, but it should be immobilized in a short arm cast for 3 weeks.

FRACTURES OF THE SCAPHOID

The scaphoid is the carpal bone that is most prone to fracture (Fig. 7-41). This injury also occurs as the result of a fall on the outstretched hand. The blood supply to this bone frequently enters the distal portion. Consequently, fractures that occur through the midportion of the bone may lead to avascular necrosis of the proximal fragment. This complication almost always occurs in more proximal fractures. Nonunion is also more frequent following this injury. These fractures are important because a delay in the diagnosis can contribute to the risk of nonunion.

THE SPRAINED WRIST

Fractures of the Hand

Fig. 7-45 Normally, the axes of the flexed fingers point to the navicular (dot). Malunion with rotation will cause the fingers to overlap when a fist is made. The resultant functional disability may be great.

FRACTURES OF THE METACARPAL

Fractures of the shaft of the finger metacarpal often present with dorsal angulation because of the action of the interosseous muscles (Fig. 7-47). Fractures that are in good alignment and apposition will heal satisfactorily in 3 to 4 weeks. Slight shortening less than 4 to 5 mm may be accepted. A short arm ulnar or radial “gutter” splint or a volar splint incorporating an aluminum splint and extending over the finger provides adequate immobilization.

Fractures of the neck of the metacarpal are common in the small finger (Fig. 7-48). These commonly occur in fist fights and are sometimes called “boxer’s fractures.” Clinically, there is swelling over the fracture site and depression of the “knuckle” of the affected finger. Impacted, stable fractures with minimal angulation are treated with a compression dressing for 1 week followed by gradually increasing active exercises. Radiographs are repeated in 1 week to assess position. Minimally angulated unstable fractures are immobilized in an ulnar gutter splint incorporating the ulnar two fingers. Fractures with angulation greater than 25 to 30 degrees should be reduced and immobilized in a plaster or fiberglass gutter splint for 4 weeks. Even if fractures of the ring or small finger metacarpal necks heal with a mild amount of angulation, the functional result is usually good because of the high mobility of the carpometacarpal (CM) joints of these fingers. However, the patient must be warned that the “knuckle” will never be as prominent when a fist is made. The same fracture in a small child will usually correct itself with further growth if the child is young enough. Open reduction is occasionally indicated in severely angulated fractures. Fractures of the index and long fingers are less forgiving than those of the ring and small fingers, and angulation of 15 degrees may require reduction. These should probably be referred if there is any doubt about the alignment.

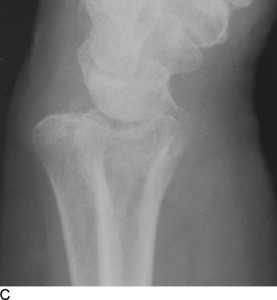

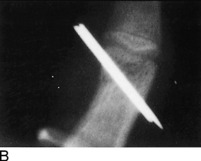

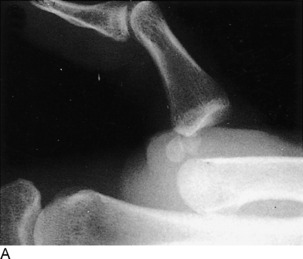

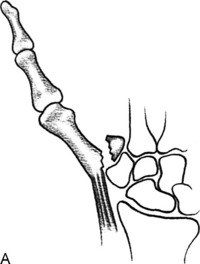

Bennett’s fracture is actually an intraarticular fracture-dislocation that occurs at the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb (Fig. 7-49). The injury involves a large portion of the metacarpal base, creating instability. Because of the pull of the long abductor muscle that inserts at its base, the metacarpal is dislocated proximally, leaving a large fragment behind. Most of these injuries are displaced and require exact reduction and internal fixation to preserve the function of this important joint.

Fig. 7-49 A, Bennett’s fracture of the base of the thumb metacarpal. B, The roentgenographic appearance.

A similar fracture-dislocation, sometimes called the “reverse Bennett,” occurs at the CM joint of the small finger (Fig. 7-50). Although not as potentially serious as the injury to the thumb, reduction and internal fixation are often required. Failure to recognize and properly treat this injury may lead to a weakness in grip because more power is provided by the ulnar side of the hand than the radial side.

The Rolando fracture is a comminuted intraarticular fracture of the base of the thumb metacarpal (Fig. 7-51). It is frequently difficult to restore normal anatomic alignment to the fracture, even by open reduction. The prognosis for return of normal use of this joint following a Rolando fracture is often poor. Early referral is indicated.

The extraarticular fracture of the base of the thumb metacarpal is common (Fig. 7-52). Up to 30 degrees of angulation is acceptable. A thumb spica cast is applied for 5 weeks.

FRACTURES OF THE PHALANGES

The treatment of phalangeal fractures is usually determined by the pattern of the fracture (transverse, oblique, or spiral) and whether or not the injury is stable. Undisplaced stable transverse fractures can be safely treated by buddy taping to the adjacent finger and splinting proximal to the MCP joint for 4 weeks. If the fracture is potentially unstable, the treatment is the same, but close follow-up with radiographs is important. Fractures of the proximal phalanx often angulate to the volar aspect of the hand (Fig. 7-53). This angulation is produced by the pull of the intrinsic muscles. Usually, the displaced transverse fracture can be converted to a stable injury. Reduction is usually possible by traction on the flexed finger toward the tubercle of the scaphoid. Immobilization in moderate flexion with a splint for 4 weeks is usually sufficient time for healing to occur. Close follow-up is required. (Transverse fractures tend to angulate after reduction, and spiral fractures tend to rotate and shorten.) Immobilization for 4 weeks is sufficient for healing of these fractures, and protection beyond 4 weeks can lead to stiffness.

Undisplaced spiral and oblique fractures can be treated by splinting. Those that are displaced have no inherent stability when reduced and usually require internal fixation to maintain reduction (Fig. 7-54). Oblique fractures of the proximal phalanx are a common cause of rotational malunion; prevention of this deformity must always be kept in mind when treating these injuries. Unstable displaced fractures usually require open reduction and internal fixation.

Fig. 7-54 Oblique fracture of the proximal phalanx with malrotation. Always evaluate for proper rotation.

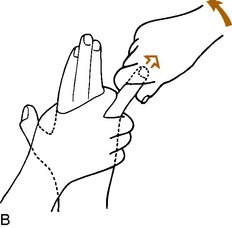

The common epiphyseal fracture of the base of the proximal phalanx of the small finger is usually a type II Salter fracture and is usually displaced into abduction (Fig. 7-55). It is reduced with the patient under local anesthesia by applying traction with the finger in slight flexion and then adducting the finger against a pencil or the physician’s finger, which acts as a fulcrum. It is taped to the ring finger and immobilized with a padded splint for 3 to 4 weeks.

Fractures of the middle phalanx may angulate volarward or dorsally (Fig. 7-56). Traction with manipulation of the fracture will usually effect a reduction. The finger is splinted for 4 weeks.

Dislocations of the Fingers

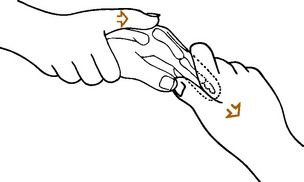

MP dislocations are not common and are most likely to involve the thumb. They may be classified as simple or complex. Simple dislocations may be reduced by traction and manipulation (Fig. 7-57). If the MP joint is stable after reduction, buddy taping to the adjacent finger for 2 to 3 weeks is usually sufficient. If it is unstable, referral is indicated. Most dislocations involving the thumb are simple.

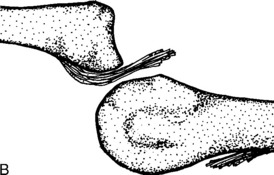

Dislocations of the fingers are more likely to be complex. These dislocations usually have soft tissue interposed in the joint, or the metacarpal neck is buttonholed through a window in the soft tissue (Fig. 7-58). It is usually impossible to treat them by closed methods. Some improvement may seem apparent after the attempted reduction, but the joint does not “snap” back into place and does not feel reduced. Reduction of the complex MP dislocation is prevented by the soft tissue interposed between the surfaces or tightened around the metacarpal head. The more traction and pressure applied to the finger, the tighter the soft tissue becomes. Open reduction is usually necessary.

IP dislocations are very common injuries and occur most often in the athlete (Fig. 7-59). Most of them involve the PIP joint and are usually dorsal in direction. They are able to be reduced by simple traction or by increasing the angular deformity, applying traction and digital pressure to the distal portion, and manipulating it into flexion. Digital block may be needed. Roentgenograms are always repeated following the reduction to exclude avulsion fractures. Dorsal PIP joint dislocations sometimes cause disruption of the volar plate, although this usually heals, and the joint is generally stable immediately following reduction. If the finger is stable after reduction, it may be buddy taped to an adjacent finger for 2 to 3 weeks. If the dislocation is unstable following reduction, referral is advised.

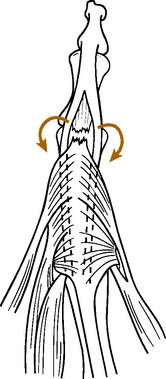

The rare volar PIP dislocation has the potential for rupture of the central slip and the formation of the boutonniere deformity (Fig. 7-60). Following reduction, this injury should be referred to a hand specialist because the central slip often requires surgical repair.

DIP joint dislocations are rare. Following reduction, they should be splinted for 2 to 3 weeks.

Miscellaneous Disorders

CARPOMETACARPAL BOSS

This abnormality develops in the same area as the usual dorsal ganglion cyst although it is present slightly distal to where the typical ganglion presents. The deformity is a bony prominence that develops at the base of the index and long finger metacarpals (Fig. 7-61). The etiology is unknown, although repetitive trauma may be a factor. An osteophyte or bony thickening develops at these CM joints and may become painful. Treatment is usually conservative with splinting and anti-inflammatory medication. Surgical removal is occasionally necessary.

MUCOUS CYSTS

These cysts are benign lesions that are similar to ganglia. They usually develop on the dorsal aspect of the DIP joints of the index or long fingers and are usually associated with osteoarthritis and osteophytes of the joint (Fig. 7-62). Heberden’s nodes are also commonly present. They may produce grooving of the nail of the affected digit. Mucous cysts are characteristically located on one side of the extensor tendon. Treatment ranges from aspiration/needling with steroid injection to excision, and there is a fairly high recurrence rate regardless of treatment.

RAYNAUD’S DISEASE AND RAYNAUD’S PHENOMENON

Raynaud’s disease is a benign, idiopathic paroxysmal vasospasm that occurs primarily in young women and usually affects the fingers and toes. The term “disease” is used when no cause can be found. The “attacks” are frequently daily and are often precipitated by cold or emotional stress. They are typically symmetric and bilateral and are relieved by warming the affected area. (If symptoms are unilateral, mechanical obstruction may need to be ruled out.) Extreme pallor is followed by cyanosis and then by hyperemia. Serious sequelae are rare, although small areas of gangrene occasionally occur if the disorder is of many years’ duration. Treatment is directed at avoiding cold situations that trigger vasoconstriction. Reassurance, dressing sensibly (often with gloves), and avoiding sudden temperature changes are important. Stress management and avoiding tobacco products are also necessary. Medication is usually not required.

HYPOTHENAR HAMMER SYNDROME

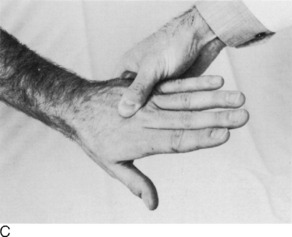

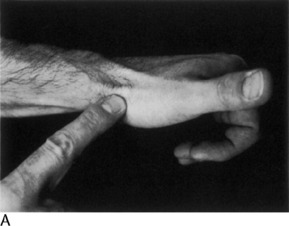

Occlusion of the ulnar artery at the wrist may produce symptoms similar to those seen with ulnar tunnel syndrome. This disorder is usually secondary to some repetitive trauma to the ulnar aspect of the hand, such as that which occurs when the hand is used as a mallet. This produces a thrombosis of the ulnar artery and results in ischemic manifestations, such as pain, pallor, paresthesias, cold intolerance, and decreased temperature of the affected digits. Local tenderness may be present, and a mass may be palpable. Allen’s test is frequently positive (Fig. 7-63). Treatment is mainly symptomatic and is directed at avoiding the offending practice. The symptoms may resolve in many cases without any further treatment. Vasodilators and sympathetic blocks are often tried. Surgical intervention may be necessary if symptoms fail to respond to conservative treatment. Some patients are still cold intolerant in the small finger regardless of treatment.

ENCHONDROMA

This is a benign tumor often seen in the hand. It is usually discovered only when a pathologic fracture occurs, sometimes with minor trauma (Fig. 7-64). Otherwise, it does not cause symptoms.

Treatment is directed to the fracture, at least initially. The benign nature of the condition is usually apparent radiographically. If there is doubt, other studies or even biopsy may be needed. Recurrent fractures may require curettage and bone grafting.

Allen MJ. Conservative management of finger tip injuries in adults. Hand. 1980;12:257-265.

Bendre AA, Hartigan BJ, Kalainov DM. Mallet finger. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:336-344.

Benson LS, Williams CS, Kahle M. Dupuytren’s contracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:24-35.

Barton NJ. Fractures of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:159-167.

Bishop AT, Beckenbaugh RD. Fracture of the hamate hook. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13:135-139.

Borden S4th. Traumatic bowing of the forearm in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:611-616.

Boswick JA, Kilgore ES, Watson HK. Symposium: Dupuytren’s Contracture. Contemp Orthop. 1988;16:71.

Bowers WH, Hurst LC. Gamekeeper’s thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:519-524.

Boyes JH. Bunnell’s surgery of the hand, ed 5. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co, 1970.

de Oliveira JC. Barton’s fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:586-594.

Entin MA. Repair of extensor mechanism of the hand. Surg Clin North Am. 1960;40:275-285.

Fassler PR. Fingertip injuries: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1996;4:84-92.

Fisk GR. The wrist. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:396-407.

Flatt AE. The care of minor hand injuries, ed 3. St Louis: CV Mosby, 1972.

Frand PL. An update on Dupuytren’s contracture. Hosp Med. 2001;62:678-681.

Hill NA. Dupuytren’s contracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1439-1443.

Kaplan EB. Functional and surgical anatomy of the hand, ed 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1965.

Leddy JP. Infections of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11:294-297.

McFarlane RM. On the origin and spread of Dupuytren’s disease. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:385-390.

Muddu BN, Morrias MA, Fahmy NR. The treatment of ganglia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:147.

Nagle DJ. Evaluation of chronic wrist pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:45-55.

Osterman AL. The double crush syndrome. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:147-155.

Peh WC. Digital enchondroma. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:416.

Rang MD. Children’s fractures, ed 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1983.

Rayan G, Flournoy D. Chronic paronychia from multiple organisms. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13:790.

Ring D, Guss D, Malhotra L. Idiopathic arm pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1387-1391.

Rockwell PG. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1113-1116.

Rockwood CA, Green DP. Fractures in adults. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1984.

Roysam GS. The distal radio-ulnar joint in Colles’ fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:58-60.

Saldana M. Trigger digits: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:246-252.

Scheyer RD, Haas DC. Pyridoxine in carpal tunnel syndrome. Lancet. 1985;2:42.

Schwartz RG. Cumulative trauma disorders. Orthopedics. 1992;15:1051-1057.

Upton AR, McComas AJ. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet. 1973;2:359-362.

Viera AJ. Management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:265-272.

Walsh HP, McLaren CA, Owen R. Galeazzi fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:730-733.

Wehbe MA, Schneider LH. Mallet fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:658-669.

Wilgis EF. Treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome. JAMA. 2002;288:1281-1282.