16 The forearm, wrist, and hand

So much in everyday life depends upon the efficient working of the hand, and so great is the practical and economic consequence of its disablement, that the care of the diseased or injured hand has become one of the most vital branches of orthopaedic surgery. It is also one of the most fascinating.

SPECIAL POINTS IN THE INVESTIGATION OF FOREARM, WRIST, AND HAND COMPLAINTS

Steps in clinical examination

A suggested routine of clinical examination is summarised in Table 16.1.

Table 16.1 Routine clinical examination in suspected disorders of the forearm, wrist, and hand

| 1. LOCAL EXAMINATION OF THE FOREARM, WRIST, AND HAND | |

| Inspection | |

| Bone contours | Metacarpo-phalangeal joints— |

| Soft-tissue contours | Flexion–extension; adduction– |

| Colour and texture of skin | abduction |

| Scars and sinuses | Interphalangeal joints—Flexion–extension |

| Palpation | Power |

| Skin temperature | Power of each muscle group in control of: |

Movements at the wrist

Like the elbow, the wrist comprises two distinct components:

The movements at each component must be examined independently.

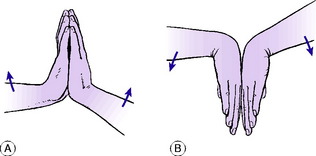

A rapid and reasonably accurate method of comparing the range of flexion– extension movement on the two sides is as follows: To judge the range of extension: The patient places the palms and fingers of the two hands in contact in the vertical plane and lifts the elbows as far as he can while keeping the ‘heels’ of the hands together (Fig. 16.1). The angle between hand and forearm is easily compared on the two sides. To judge the range of flexion the manoeuvre is reversed. The patient places the backs of the hands together, with the fingers directed vertically downwards, and lowers the elbows as far as he can (Fig. 16.1). The angle between hand and forearm is compared on the two sides.

The inferior radio-ulnar joint. The normal range is 90 ° of supination and 90 ° of pronation. To determine the range accurately the patient’s elbows must be flexed to a right angle in order to eliminate rotation at the shoulder (see Fig. 15.1).

Movements of the hand

Movements of the hand occur mainly at three groups of joints:

Carpo-metacarpal joint of thumb. This joint allows movement in five directions: flexion, or movement of the thumb metacarpal medially in the plane of the palm; extension, or movement of the thumb metacarpal laterally in the plane of the palm; adduction, or movement of the metacarpal towards the palm in a plane at right angles to it; abduction, or movement of the metacarpal away from the palm in a plane at right angles to it; and opposition, or rotation of the metacarpal to bring the thumb nail into a plane parallel with the palm (Fig. 16.2).

Power

Test the power of each movement in turn. In the hand this examination demands considerable patience, for each muscle group must be tested individually. Thus in the thumb it is necessary to test the abductors, the adductor, the extensors (longus and brevis), the flexors (longus and brevis), and the opponens. In the fingers test the flexors (profundus and superficialis), the extensor digitorum and extensor indicis, the interossei and the lumbricals. Grip: Test the power of grip, which demands the combined action of the flexors and extensors of the wrist and the flexors of the fingers and thumb.

Nerve function

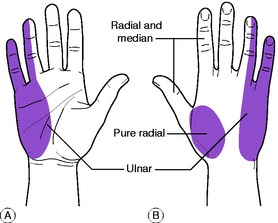

The state of the median, ulnar, and radial nerves is determined by tests of sensory function, motor function, and sweating. The ulnar nerve normally supplies sensation to the ulnar side of the hand together with the little finger and half the ring finger (Fig. 16.3).

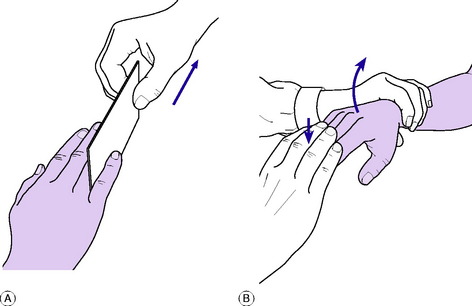

The remainder is largely innervated from the median nerve with some overlap on the dorsum of the hand from the radial nerve (Fig. 16.3). Only a small skin area at the base of the thumb is purely supplied by the radial nerve. Intact function of the median nerve is indicated by ability to oppose the thumb to the little finger (see Fig. 16.2). Intact ulnar nerve function is shown by ability to spread the fingers apart and to bring them together again to grip a card between the middle and ring fingers (Fig. 16.4). An index of radial nerve function is the ability to extend the thumb and to extend the fingers at the metacarpo-phalangeal joints.

Circulation

The state of the circulation is assessed from the condition of the arterial pulses, the warmth and colour of the digits, the capillary return at the nail beds, and cutaneous sensibility. It should be remembered that sensibility to touch in the fingers is a most useful index of the adequacy of the circulation. Nerves require a blood supply to enable them to conduct impulses, and if the circulation is interrupted sensibility is quickly lost.

DISORDERS OF THE FOREARM

ACUTE OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of acute osteomyelitis, p. 85)

Acute osteomyelitis is rather uncommon in the forearm bones. As in other sites, the infection may be blood-borne (haematogenous) or it may be introduced from without, usually in consequence of a compound fracture. The haematogenous type occurs mainly in children. It affects the radius more often than the ulna, and the lower metaphysis rather than the upper (see Fig. 7.3B).

The clinical features and treatment are like those of acute osteomyelitis elsewhere.

CHRONIC OSTEOMYELITIS (General description of chronic osteomyelitis, p. 90)

As in other bones, chronic osteomyelitis of the radius or ulna follows an acute infection.

BONE TUMOURS IN THE FOREARM AND HAND

Benign tumours (General description of benign tumours of bone, p. 106)

Chondroma

Enchondroma, which grows within the bone and expands it, is prone to occur in the metacarpals and phalanges of the hand presenting with deformity or pathological fracture. The tumour may be solitary, but in the condition of multiple enchondromatosis, or Ollier’s disease, the tumours may affect many bones in the hand causing ugly swelling and deformity of the fingers (Fig. 16.5). Malignant transformation is hardly known in a solitary chondroma of a bone of the hand, but it is a possibility in cases of multiple enchondromatosis, leading to chondrosarcoma.

Treatment. If small, the tumour should be treated expectantly and fractures normally heal with simple splintage. Operation is required only if the tumour is found to be enlarging. Large tumours should be excised and sent for routine histological examination, the bone substance being restored by cancellous bone grafts.

Enchondromas of long bones are less common in the forearm, though these bones may be affected by multiple osteochondroma in the hereditary condition of diaphyseal aclasis (p. 63). These tumours may interfere with the normal growth of the affected bone resulting in shortening and deformity.

Giant-cell tumour (osteoclastoma)

The lower end of the radius is one of the common sites in the upper limb for the development of a giant-cell tumour, which though classed as benign may show invasive tendencies. The lower end of the ulna is also susceptible. The tumour extends into the former epiphysial region close up to the articular surface (Fig. 16.6).

Treatment. If the tumour is in the lower end of the radius radical excision and replacement by a suitable bone graft is to be recommended. A graft obtained from the upper part of the fibula is suitable because its shape matches that of the original bone. Ideally, the graft should be taken with the supplying artery and veins, which are anastomosed to suitable vessels in the recipient area by a microsurgical technique. If the lower end of the ulna is the part affected the bone should be excised up to a point well proximal to the tumour. The resulting disability is negligible.

VOLKMANN’S ISCHAEMIC CONTRACTURE1

Cause. It is caused by ischaemia of the flexor muscles, brought about by injury to, or obstruction of, the brachial artery near the elbow; or by tense oedema of the soft tissues of the forearm constrained within an unyielding fascial compartment.

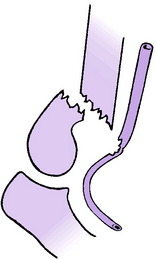

Any major fracture in the elbow region or upper forearm may lead to arterial occlusion. That most commonly responsible is a supracondylar fracture of the humerus with displacement, the brachial artery being severed or contused by the sharp lower end of the main shaft fragment (Fig. 16.7). Contusion alone is sufficient to interrupt the flow of blood, because the artery goes into spasm and its lumen may be occluded by thrombosis.

In some cases the cause of the vascular obstruction is an over-tight plaster or bandage.

On examination in the incipient stage, the fingers are white or blue, and cold. The radial pulse is absent. Active finger movements are weak and painful. Passive extension of the fingers is especially painful and restricted. There may or may not be evidence of interruption of nerve conductivity – namely, anaesthesia of the fingers and paralysis of the small muscles of the hand.

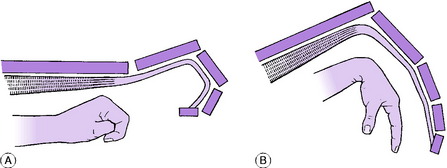

In the established condition, which develops gradually within a few weeks of the injury, there is a striking flexion contracture of the wrist and fingers, from shortening of the fibrotic forearm flexor muscles (Fig. 16.8). Sensory and motor paralysis of the hand may persist as complicating factors, but they do not form an essential feature of Volkmann’s contracture as such.

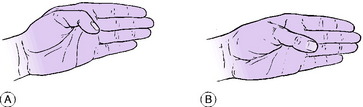

Volkmann’s ischaemic contracture bears no real resemblance to Dupuytren’s contracture (p. 321), for it affects the wrist as well as all the joints of the fingers, and there is no palpable thickening in the palm. Moreover the contracture is demonstrably brought about by shortening of the flexor muscles, because if the wrist is flexed passively to relax the flexor tendons the range of extension at the finger joints is increased. Conversely, if the tendons are relaxed by flexing the fingers fully the range of wrist extension is increased (Fig. 16.9).

First step. All splints, plaster, and bandages that might be obstructing the circulation are removed. In the case of a fracture, gross displacement of the fragments is corrected as far as possible by gentle manipulation and a well-padded plaster splint is applied. Likewise if the elbow is dislocated it must be reduced without delay. Heat cradles or hot bottles are applied over the other three limbs and trunk to promote general vasodilation.

ARTICULAR DISORDERS OF THE WRIST AND HAND

MADELUNG’S DEFORMITY1 (Radio-ulnar dyschondrosteosis)

Madelung’s deformity (radio-ulnar dyschondrosteosis) is a congenital subluxation or dislocation of the lower end of the ulna, from malformation of the bones. Although it is seemingly a localised disorder there may be minor generalised abnormalities of bone structure, often with short stature.

The deformity varies in degree from a slight prominence of the lower end of the ulna at the back of the wrist, to complete dislocation of the inferior radio-ulnar joint with marked radial deviation of the hand (Fig. 16.10). The more severe types of deformity may be associated with congenital absence or hypoplasia of the radius.

PYOGENIC ARTHRITIS OF THE WRIST AND HAND (General description of pyogenic arthritis, p. 96)

Pyogenic arthritis of the wrist is uncommon. Infection may be haematogenous, or it may be introduced through a penetrating wound. Spread from a focus of osteomyelitis is rare, partly because osteomyelitis itself is uncommon in the forearm bones, and partly because the lower metaphysis of the radius is entirely outside the capsule of the joint. (The lower metaphysis of the ulna is partly intracapsular (see Fig. 7.2).)

The clinical features and treatment of pyogenic arthritis are similar to those at other sites.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS OF THE WRIST AND HAND (General description of rheumatoid arthritis, p. 134)

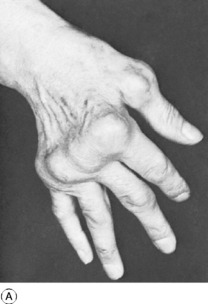

Rheumatoid arthritis commonly affects the wrists and hands and is a major cause of serious loss of function and of ugly deformity. Usually many or all of the joints of the hand are affected, though occasionally the disease may begin in a single joint. Affected joints are swollen from synovial thickening, and movement is restricted. In the later stages articular cartilage and the underlying bone are eroded, and the fingers tend to deviate medially (‘ulnar drift’), with dorsal prominence of the metacarpal heads and characteristic visible deformity (Fig. 16.11A). At the wrist joint the disease commonly results in dorsal subluxation and dislocation of the ulnar head accompanied by subluxation of the carpus on the radius and radial deviation of the hand. Radiographs do not show any abnormality at first. Later, there is diffuse rarefaction of the bones. Later still, in progressive disease, destruction of cartilage leads to narrowing of the joint space (Fig. 16.11B), and the subchondral bone may be eroded.

Rupture of tendons. Both the extensor and the flexor tendons are liable to spontaneous rupture, from softening or fraying where they lie within inflamed synovial sheaths. The extensor pollicis longus, extensor digitorum, and extensor digiti minimi are the tendons that most commonly rupture.

Treatment

Conservative treatment. The general plan of treatment is like that for rheumatoid arthritis as a whole (p. 137). It will usually include the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or in more resistant disease second-line drug therapy may be required with gold, penicillamine, or immuno-suppressive agents. Cortisone and related steroids should be avoided if possible because of their undesirable side effects. Physiotherapy is of value: it should take the form of warm water or wax baths, with mobilising exercises and encouragement in active use of the hand. During an acute exacerbation the wrist joint may be immobilised temporarily in a moulded polythene splint or plaster of Paris back slab, but immobilisation is never advised for the joints of the fingers other than with a dynamic active splint.

Operative treatment. In carefully selected patients operation can be a valuable adjunct to conservative treatment, though it can never replace it. It should never be undertaken lightly, but only after careful deliberation and full discussion with the patient as well as the other members of the treatment team. Operations, particularly soft-tissue procedures, are often more rewarding when carried out in the fairly early stages of the disease, before deformity from changes in the joints and soft tissues has become fixed and irreversible. Depending upon the nature of each individual case, operation may take one or more of the following forms.

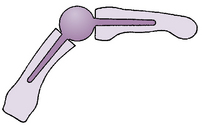

Arthroplasty. When the metacarpo-phalangeal or interphalangeal joints are badly disorganised arthroplasty by the insertion of a flexible silicone-rubber (‘Silastic’) prosthesis may sometimes be appropriate (Fig. 16.12). But the patient must be prepared to cooperate in a long programme of rehabilitation afterwards. The improvement gained is often cosmetic rather than functional. The benefit is not always lasting and deformity may recur because of breakage or loosening of the prosthesis.

Tendon repair or replacement. Ruptured tendons may be repaired by suture or by grafting when practicable, or their lost function may be compensated by a tendon transfer operation (p. 44).

Carpal tunnel decompression. Division of the transverse carpal ligament and excision of the proliferative synovium will provide adequate decompression for the median nerve when neuropathy is present.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE WRIST (General description of osteoarthritis, p. 140)

Radiographic features. Radiographs show narrowing of the cartilage space and sharpening or spurring of the bone at the joint margins. The underlying causative condition (for example, an ununited fracture of the scaphoid bone) is usually evident (Fig. 16.13).

Treatment. In mild cases the condition is best left alone, especially if the patient can avoid subjecting the wrist to heavy stress. When active treatment seems necessary, a choice must be made between conservative and operative methods. Conservative treatment can only diminish the symptoms; it can never remove them. Nevertheless it is usually worth a trial. The most useful method is to provide support for the wrist by a detachable splint made from moulded plastic (Fig. 16.14).

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE JOINTS OF THE HAND

The metacarpo-phalangeal joints and the interphalangeal joints of the hand are frequently the site of osteoarthritis in the elderly. Such manifestations are relatively unimportant and in most cases treatment is not required. Commonly involved are the carpo-metacarpal joint of the thumb (trapezio-metacarpal joint) (Fig. 16.15A) and the distal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 16.15B).

Osteoarthritis of the trapezio-metacarpal joint

This is a common affection in women beyond middle age but it may also occur in younger persons, especially when there has been previous injury such as a fracture of the base of the first metacarpal bone involving the joint (Bennett’s fracture-subluxation). The arthritis may seriously impair the function of the thumb because of pain.

On examination the trapezio-metacarpal joint is prominent and slightly thickened. Active or passive movements of the thumb metacarpal cause pain. The range of movement at this joint varies widely even in normal individuals; so its measurement is of little practical value, though comparison with the opposite hand may be a guide to the extent to which movement is impaired. In cases of severe arthritis there may be very little remaining movement.

Radiographs show narrowing of the cartilage space and sharpening or spurring of bone at the joint margins (Fig. 16.15A). In many cases the joint is subluxated.

Osteoarthritis of interphalangeal joints

This leads to pain and stiffness especially in the distal interphalangeal joints. Characteristically the formation of osteophytes is a prominent feature, with the appearance of ugly swellings known as Heberden’s nodes (Fig. 16.15B). Active treatment is not required.

KIENBÖCK’S DISEASE1 (Osteochondritis of the lunate bone)

Pathology. In its behaviour the disease resembles osteochondritis of developing epiphysial centres in children (p. 130), such as Perthes’ disease: in effect, it is a form of avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis). The bone becomes granular in texture, small dense fragments being interspersed with softened areas. In this state the bone eventually crumbles, and under the pressure imposed by muscle action and use of the wrist it gradually becomes compressed into a thin saucer-shaped mass. The overlying cartilage dies. After about two years the bone texture is restored to normal, but the bone remains deformed and lacks a smooth cartilaginous covering. The bone behaves like a piece of grit in a bearing and leads gradually to the development of osteoarthritis of the wrist.

Radiographs are diagnostic. In the early stages the lunate bone appears slightly more dense than the surrounding bones, and if its depth is compared with that of the lunate bone of the sound wrist it is seen to be reduced, though only slightly at first (Fig. 16.16). Later, the bone has a fragmented appearance, small areas of increased density being scattered through it, and the flattening of the bone becomes obvious. Later still, signs of osteoarthritis of the wrist are evident.

In late cases, if severe osteoarthritis is already present, excision of the lunate bone is of no avail. Treatment should then be the same as for osteoarthritis of the wrist (p. 307).

EXTRA-ARTICULAR DISORDERS ABOUT THE WRIST AND HAND

ACUTE INFECTIONS OF THE FASCIAL SPACES OF THE HAND

Classification

If minor superficial infections are excluded there are six types to be considered:

Cause. All types are caused by infection with pyogenic bacteria. The usual causative organism is the Staphylococcus aureus, but the Streptococcus and occasionally other bacteria may be responsible. Minor injury such as a prick, abrasion, or blister usually provides the route by which infection can enter. Manual work in dirty conditions is clearly a factor that favours infection.

Within the limits imposed by these principles there is often more than one way of performing the actual drainage operation. However, it should be stressed that a knowledge of the anatomy of the fascial spaces1 of the hand is indispensable for the correct treatment of hand infections.

SPECIAL FEATURES OF INDIVIDUAL LESIONS

Nail-fold infection (paronychia)

This is one of the commonest but least serious types of hand infection. The subcuticular plane beneath the nail fold is potentially continuous, at the base and sides of the nail, with the subungual space deep to the nail. Infection beginning in the nail fold may therefore easily spread under the nail (Fig. 16.17), and the resulting abscess cannot be drained effectively unless part of the nail is removed.

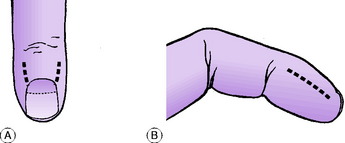

Treatment. In this type of infection conservative measures are often successful if begun within a few hours of the onset. When local suppuration has occurred the subcuticular abscess is drained by raising the cuticle from the nail or by raising it as a short flap after incising it vertically at one or both corners (Fig. 16.18A). If pus has extended under the nail the proximal third of the nail must also be removed.

Pulp-space infection (whitlow)

This is almost as common as nail-fold infection. The interval between the front of the distal phalanx and the skin is traversed by tough fibrous partitions, which subdivide the space into numerous fat-filled cells (like the cells of a honeycomb) disposed at right angles to the skin surface (Fig. 16.17). Infection occurring in this tough tissue is virtually within a closed compartment: tissue pressure rises rapidly and accounts for early throbbing pain.

Treatment. Conservative measures are seldom successful except in the earliest stages. Surgical drainage is effected well by a lateral incision just in front of the plane of the terminal phalanx (Fig. 16.18B); it is deepened transversely across the pulp of the finger but should not extend proximally beyond a point half a centimetre distal to the terminal skin crease lest the flexor tendon sheath be inadvertently opened. An alternative method is to incise directly into the pulp over the centre of the abscess, a technique that is to be preferred if the abscess is already threatening to point at the surface.

Subcutaneous infections (other than pulp-space infections)

Treatment. Surgical drainage is by a short incision appropriately placed to reach the abscess without harming important structures or leaving an awkward scar. In the case of a web-space infection the incision should not divide the skin fold of the web: a short transverse incision in the palm just proximal to the skin fold is adequate (see Fig. 16.20B).

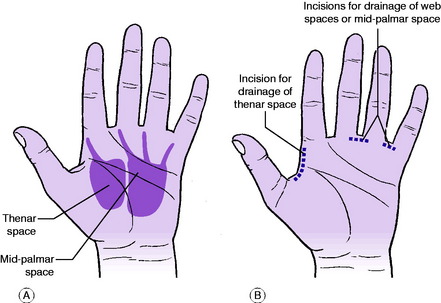

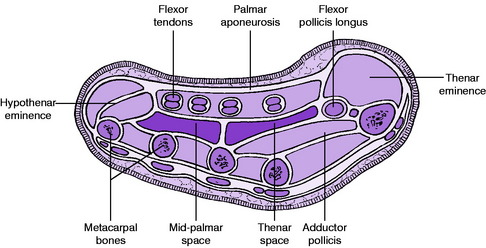

Thenar space infection

This is a well-defined entity but it is very uncommon. It may arise by extension from a subcutaneous lesion or a tendon sheath infection. The thenar space lies deeply under the lateral (radial) half of the hollow of the palm. It is the interval between the adductor pollicis muscle behind and the flexor tendon of the index finger and the first and second lumbrical muscles in front. Medially it is separated from the mid-palmar space by a fibrous septum that extends deeply from the fascia on the deep surface of the flexor tendons to the fascia covering the interossei and adductor pollicis muscle (Figs 16.19 and 16.20A). The space is prolonged forwards into the delicate sheath that surrounds the first lumbrical muscle. It sometimes communicates also with the second lumbrical canal. The lumbrical canals thus provide a potential communication between the subcutaneous web spaces and the thenar space: in practice, however, it is rare for infection to spread along this route.

Clinical features. The radial half of the palm is ballooned out and the swelling extends to the dorsal aspect of the web between thumb and index finger. Treatment: Drainage is by an incision at the dorsal aspect of the first web space (Fig. 16.20B).

Mid-palmar space infection

This is also uncommon. It resembles the thenar space infection, but the swelling is confined to the ulnar half of the palm. It usually arises by extension from a subcutaneous lesion or a tendon sheath infection. The mid-palmar space lies under the medial (ulnar) half of the hollow of the palm. It is the interval between the interossei and metacarpal bones behind and the flexor tendons (in their sheaths) of the middle, ring, and little fingers in front (Fig. 16.19). Laterally, it is separated from the thenar space by the fibrous septum already described. The space is prolonged forwards into the sheaths of the second, third, and fourth lumbrical muscles (Fig. 16.20A). Again, despite the potential communication between a web space and the mid-palmar space along the lumbrical canals, web-space infection very seldom spreads deeply to involve the palm.

Clinical features. The ulnar half of the palm is ballooned out. Movements of the fingers are restricted and painful.

Treatment. Drainage can be established through the web space between the middle and ring fingers or through that between the ring and little fingers (Fig. 16.20B).

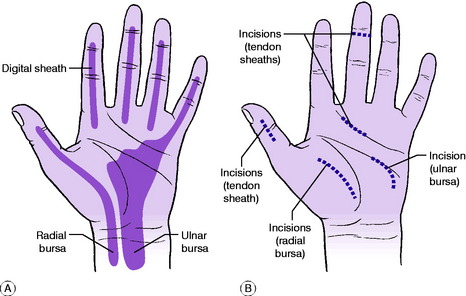

Tendon sheath infection

This is rare, but important because prompt treatment is essential if the function of the finger is to be preserved. Distinction must be made between the tough fibrous sheaths, which exist only in the digits, and the flimsy synovial sheaths, which line the fibrous sheaths and, in the case of the thumb and little finger, extend proximally into the palm. In acute infections of the tendon sheaths (acute infective tenosynovitis) the pus is within the synovial sheath and it is confined only by the limits of the sheath. The flexor sheaths of the index, middle, and ring fingers end proximally at the level of the transverse palmar skin crease (Fig. 16.21A). The sheaths of the thumb and little finger extend proximally through the palm to end two or three centimetres above the level of the wrist. The proximal part of the sheath for the thumb is known as the radial bursa. The sheath for the little finger opens out proximally into the ulnar bursa, which encloses the grouped tendons of flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus (Fig. 16.21A).

Clinical features. The finger is swollen throughout its length, and acutely tender over the flexor tendon sheath. It is held semiflexed and the patient is unwilling to extend it because of pain.Complications: These are:

Treatment. Systemic antibiotic therapy is begun immediately. The sheath is opened at its proximal end in the palm and at its distal end (Fig. 16.21B), and irrigated with antibiotic solution through a fine tube passed along the sheath; the tube is withdrawn and the wounds are packed lightly open.

If the radial bursa or the ulnar bursa is infected it must be drained and irrigated through an additional incision in the palm (Fig. 16.21B).

CHRONIC INFECTIVE TENOSYNOVITIS (Including compound palmar ganglion)

Pathology. The flexor tendon sheaths in the lower forearm and hand are those most commonly affected. The affected sheaths are greatly thickened and show the changes of chronic inflammation. There may be histological evidence of tuberculosis in the thickened tissue. The sheaths often contain an excess of fluid and there may be collections of small fibrinous bodies. The tendons themselves are affected only slightly.

Clinical features. There is a gradual onset of swelling, with mild aching pain, in the region of the affected tendon sheaths – usually the flexor sheaths of the lower forearm and hand. The function of the fingers and thumb is impaired with moderate restriction of flexion and extension of the digits. The swelling is confined to the line of the tendon sheaths in the front of the forearm and the proximal part of the palm (Fig. 16.22). In many cases fluctuation can be elicited between the forearm swelling and the swelling in the palm. This physical sign led to the use of the term compound palmar ganglion, though this is a misnomer as the common ganglia around the wrist joint arise from the synovial cavity of the joint and not the tendon sheath.

Treatment. In mild cases in which the function of the fingers and thumb is not impaired conservative treatment is advised. In tuberculous cases a course of the appropriate antibacterial drugs is given (see p. 102).

SOFT-TISSUE TUMOURS IN THE HAND (General description of soft-tissue tumours, p. 157)

Soft-tissue tumours are uncommon in the hand but special mention must be made of an unusual tumour that is the second most common cause of swelling in the hand after simple ganglion cyst. This is the giant-cell tumour of tendon sheath (localised nodular tenosynovitis).

GANGLION (Simple ganglion)

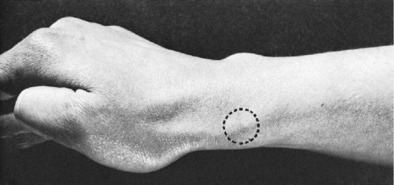

A ganglion is the commonest cystic swelling at the back of the wrist.

Clinical features. Ganglia are commonest at the back of the wrist, where they are often seen in adults of any age (Fig. 16.23). They also occur, less commonly, at the front of the wrist, or in the palm or fingers. Ordinarily there are no symptoms other than the swelling itself and, sometimes, discomfort or slight pain. On examination the swelling may be soft and obviously cystic, but more often it is tense. It is often mistaken for a bony prominence – but careful tests will show that it is fluctuant.

Complications. A ganglion arising deeply in the wrist or palm may interfere mechanically with the ulnar or the median nerve or their branches. There will be motor and usually sensory impairment in the distribution of the particular branch affected.

A ganglion that is interfering with a peripheral nerve demands operative excision without delay.

CARPAL TUNNEL SYNDROME (Compression of median nerve in carpal tunnel)

Investigations. Electrophysiological nerve conduction testing may show decreased conduction velocity in the affected part of the median nerve. This is a reliable confirmatory test if the clinical diagnosis is in doubt.

DUPUYTREN’S1 CONTRACTURE (Contracture of the palmar aponeurosis; Dupuytren’s disease)

Pathology. The palmar aponeurosis (palmar fascia) is normally a thin but tough membrane whose fibres radiate from the termination of the palmaris longus tendon at the front of the wrist to gain insertion into the proximal and middle phalanges of the fingers. It lies immediately beneath the skin. In Dupuytren’s contracture the aponeurosis, or part of it, becomes greatly thickened (often to half a centimetre or more), and it slowly contracts, drawing the fingers into flexion at the metacarpo-phalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints. The medial (ulnar) half of the aponeurosis is affected most, and serious flexion deformity is usually confined to the ring and little fingers, with only moderate deformity of the middle finger (Figs 16.24 and 16.25). The joints themselves are unaffected at first, but in long-established cases secondary capsular contractures occur. The flexor tendons in the palm are in no way affected.

Fig. 16.24 Early Dupuytren’s contracture. There is a nodule of thickened aponeurosis in the palm, opposite the base of the ring finger, with slight puckering of the skin; but so far there is no flexion contracture of the fingers.

The plantar aponeurosis in the foot is occasionally affected, but in the foot the lesion usually takes the form of a firm nodule under the instep rather than of a contracture involving the toes (Fig. 16.26). Other parts that may be affected include the penis. Thus although the hands are primarily affected, the condition is sometimes much more widespread (Dupuytren’s disease).

Clinical features. The affection is much more common in men than in women. Often both hands are affected. The earliest sign is a small thickened nodule in the mid-palm opposite the base of the ring finger (Fig. 16.24). The area of thickening gradually spreads from this point, giving rise eventually to firm cord-like bands that extend into the ring finger or little finger, or both, and prevent full extension of the metacarpo-phalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 16.25). The skin is closely adherent to the fascial bands, and is often puckered. The flexion deformity becomes progressively worse in the course of months or years.

In some cases these changes in the palm are accompanied by thickening over the dorsum of the interphalangeal joints (knuckle pads). The feet may also show nodules in the sole (Fig. 16.26). Occasionally the penis is distorted by thickened bands.

RUPTURE OR SEVERANCE OF TENDONS IN THE HAND

Most tendon divisions in the hand are caused by cuts with sharp objects such as glass or knives. Certain tendons are prone to rupture: thus the extensor tendon of a finger is easily torn from its insertion into the distal phalanx by sudden forced flexion of the finger; and the extensor pollicis longus tendon is liable to rupture spontaneously after fractures of the lower end of the radius in consequence of its becoming frayed where it crosses the roughened bone. In rheumatoid arthritis, also, spontaneous rupture – especially of an extensor tendon – is common.

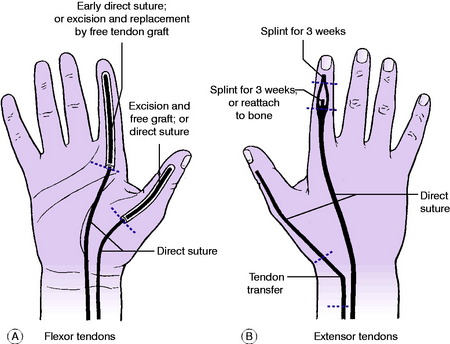

Treatment. This varies according to the tendon affected and the site of severance or rupture (see below and Fig. 16.27). Sometimes treatment is unnecessary or undesirable, but more often operative reconstruction is to be advised: the tendon is either sutured directly or replaced by a free tendon graft or by a tendon transfer, according to circumstances (see pages 46 and 44 for the principles of these methods).

SPECIAL FEATURES OF INDIVIDUAL LESIONS

Injuries of flexor tendons

Treatment. If a flexor superficialis tendon alone is divided and the flexor profundus is intact treatment may not be required, for there is virtually no disability.

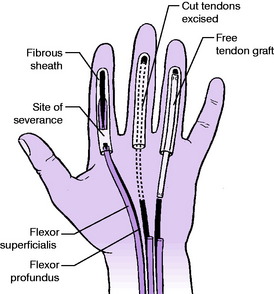

For delayed repair because of late presentation, or where there is extensive damage or loss of tendon tissue, it may be necessary to use a free tendon graft. The standard method is to remove the flexor superficialis tendon entirely (to make more room in the sheath) and to replace the whole of the digital part of the flexor profundus tendon by a free tendon graft (from the palmaris longus or from a toe extensor) sutured proximally to the profundus tendon in the palm or at wrist level, and inserted distally into a drill hole in the distal phalanx (Fig. 16.28). This method eliminates the need for a tendon junction within the sheath, which carries the risk of adhesions that may cause disabling stiffness.

Division of flexor tendons in the palm or wrist. Direct suture is advised. It may be done primarily if the wound is clean. The prognosis is good if a single tendon is affected but it is uncertain in cases of multiple tendon divisions at the front of the wrist, especially if the nerves are also injured.

Injuries of extensor tendons

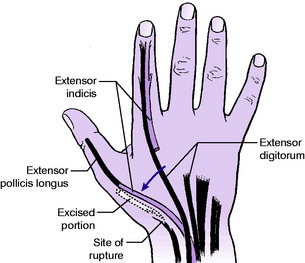

Rupture of extensor pollicis longus tendon may complicate fracture of the lower end of the radius. The tendon gives way after becoming frayed by repeated movement over the roughened lower end of the radius. Spontaneous rupture may also occur in drummers. The extensive fraying makes direct suture unsatisfactory. Treatment: A clean rupture should be sutured end-to-end. If the tendon is frayed, as is usually the case, a tendon transfer operation is to be preferred. The tendon of extensor indicis is divided at the level of the neck of the second metacarpal bone, re-routed towards the thumb, and sutured to the freshened distal stump of the extensor pollicis longus tendon (Fig. 16.29).

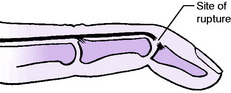

Avulsion of extensor tendon from distal phalanx of a finger. This is known as ‘mallet’ finger or ‘baseball’ finger. It is caused by sudden forced flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint – for instance, by a blow on the tip of the finger from a ball. In a few cases a small fragment of bone is avulsed with the tendon. The patient is unable fully to extend the distal interphalangeal joint (Fig. 16.30). Treatment: Immediate treatment is to splint the finger for three weeks with the distal interphalangeal joint fully extended. Splintage must be continuous and uninterrupted if a good result is to be achieved. The avulsed tendon always unites back to the bone, but often with lengthening, in which case some deformity persists. However, the disability is usually insignificant and acceptable.

ACUTE FRICTIONAL TENOSYNOVITIS (Peritendinitis crepitans; paratendinitis crepitans; repetitive stress syndrome)

Treatment. Initially, a trial should be made of local injection of hydrocortisone. If this is unsuccessful, the wrist and forearm should be immobilised in plaster of Paris for three weeks, the fingers being left free. This affords sufficient rest to allow the inflammation to resolve. Excessive use of the fingers and thumb should be avoided for two months.

DE QUERVAIN’S1 STENOSING TENOVAGINITIS (Tenovaginitis of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis)

Clinical features. The condition is five times commoner in women than men, predominantly in middle age. The main symptom is pain on using the hand, especially when movement tenses the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons (as in lifting a saucepan or a teapot). On examination there is local tenderness at the point where the tendons cross the radial styloid process (Fig. 16.31). The thickened fibrous sheaths are usually palpable as a firm nodule. Passive adduction of the wrist or thumb causes the patient to wince with pain.

‘TRIGGER’ FINGER; SNAPPING FINGER (Digital tenovaginitis stenosans)

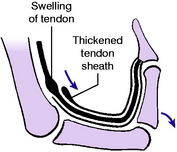

In this rather common condition thickening and constriction of the mouth of a fibrous digital sheath interfere with the free gliding of the contained flexor tendons.

Pathology. The proximal part of the fibrous flexor sheath at the base of a finger or thumb is thickened and the mouth of the sheath is constricted. The contained tendons become ‘waisted’ opposite the constriction, and swollen proximal to it. The swollen segment enters the mouth of the sheath only with difficulty when an attempt is made to straighten the finger from the flexed position (Fig. 16.32).

Clinical features. The condition occurs:

The adult type. There is complaint of tenderness at the base of the affected finger and of locking of the finger in full flexion (Fig. 16.33). The locking can be overcome either by a strong effort or by extending the finger passively with the other hand, when the flexion is released with a distinct snap. On examination there is a palpable nodule, usually slightly tender, at the base of the affected finger or thumb – that is, over the mouth of the fibrous flexor sheath. The snapping cannot be reproduced well on passive movements; it can be demonstrated only when the patient extends the finger fully with its own muscles or assists extension with the other hand.

The infantile type (contracted thumb of infants). The infant is unable to straighten the thumb, which is locked in flexion. On examination it may be possible to extend the thumb passively with a snap, but in many cases the flexed position of the joint cannot be corrected even by moderate force. A palpable nodule is present at the base of the thumb in the position of the mouth of the fibrous flexor sheath – that is, at the level of the head of the metacarpal bone. It should be noted that because the deformity is often resistant to correction this condition in infants is often mistaken for a dislocated thumb or for a congenital deformity.

EXTRINSIC DISORDERS SIMULATING DISEASE OF THE FOREARM OR HAND

TUMOUR AT THE THORACIC INLET

A mass at the thoracic inlet is an occasional cause of peripheral symptoms in the upper limb. The commonest cause is an apical tumour of the lung (Pancoast’s tumour) involving the nerves of the brachial plexus.

1 Richard von Volkmann (1830–1889) German surgeon who was Professor in Halle, Saxony and also served as an army surgeon in the Franco-Prussian War. He described the ischaemic muscle paralysis and contracture in 1881.

1 Otto Madelung (1846–1926) German general surgeon who was professor in Strasburg until after the First World War when the city was returned to France and he was forced to retire to Germany. He described the deformity in 1878.

1 Dr Robert Kienböck (1871–1953) Austrian radiologist and Professor in Vienna who began using X-rays in 1897, only 2 years after their discovery by Röntgen.

1 The term ‘space’ as used in this connection is a misnomer. It refers to the interval or plane between adjacent tissues, and in the normal hand it is only a potential space.

1 Baron Guillame Dupuytren (1777–1835) A French surgeon who rose from humble beginnings to become Surgeon-in-chief at the Hotel Dieu in Paris. He described many pathological conditions including the contracture in 1833.

1 Fritz de Quervain (1868–1940) Swiss general surgeon who was Professor of Surgery in Berne. Described the chronic tenovaginitis which bears his name in 1895.