Chapter 22 The Extremities and Peripheral Vascular Exam

A. Generalities

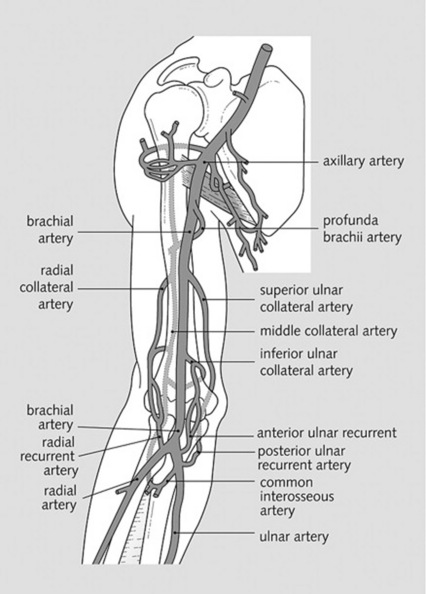

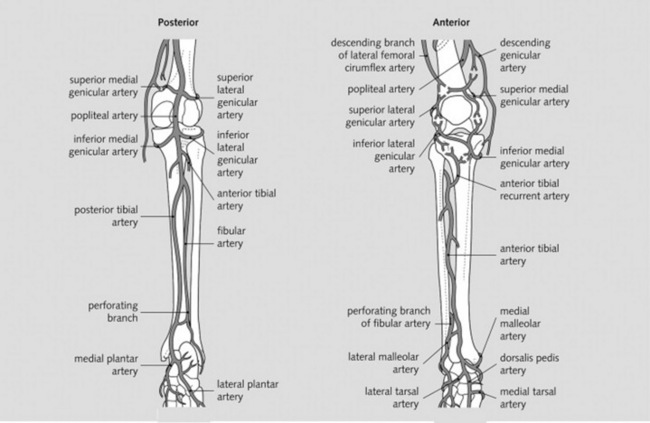

2 Which arteries should be examined in the upper and lower extremities?

The major branches of the brachial and femoral arteries (Figs. 22-1 and 22-2)

3 Which veins should be examined?

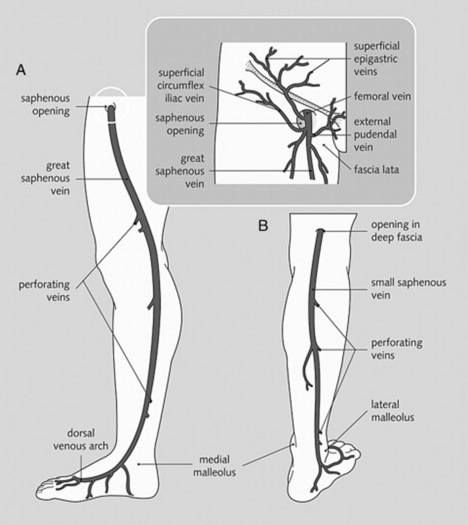

id=”u0010″/>For lower extremities, the tributaries of the saphenous system (draining into the femoral vein) (Fig. 22-3)

id=”u0010″/>For lower extremities, the tributaries of the saphenous system (draining into the femoral vein) (Fig. 22-3)

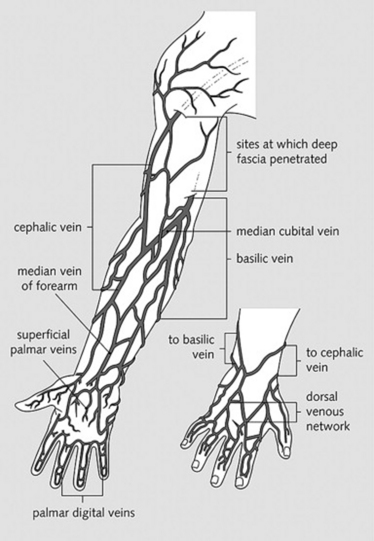

For upper extremities, the branches of the brachial veins (deep system) and of the basilic and cephalic veins (superficial system), both draining into the axillary vein (Fig. 22-4)

For upper extremities, the branches of the brachial veins (deep system) and of the basilic and cephalic veins (superficial system), both draining into the axillary vein (Fig. 22-4)

B. The Peripheral Arteries

(1) Asymmetric Pulses

(2) Raynaud’s Phenomenon

8 What is the clinical significance of Raynaud’s phenomenon?

It can precede several important disorders, including:

Connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], mixed connective tissue disease, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, and polymyositis, but especially progressive systemic sclerosis, which is present in 17–28% of patients with Raynaud’s)

Connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], mixed connective tissue disease, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, and polymyositis, but especially progressive systemic sclerosis, which is present in 17–28% of patients with Raynaud’s)

Hematologic disorders (cryoglobulinemia, polycythemia, monoclonal gammopathy)

Hematologic disorders (cryoglobulinemia, polycythemia, monoclonal gammopathy)

Arterial compression syndromes (thoracic outlet and carpal tunnel syndromes)

Arterial compression syndromes (thoracic outlet and carpal tunnel syndromes)

Vasculitis and atherosclerotic arterial disease

Vasculitis and atherosclerotic arterial disease

Recurrent trauma (use of percussion or vibratory tools)

Recurrent trauma (use of percussion or vibratory tools)

Miscellaneous disorders (hypothyroidism, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, primary pulmonary hypertension, Prinzmetal angina, acromegaly, Addison’s disease). Still, one of five patients with Raynaud’s does not seem to have any underlying disorder (i.e., Raynaud’s disease).

Miscellaneous disorders (hypothyroidism, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, primary pulmonary hypertension, Prinzmetal angina, acromegaly, Addison’s disease). Still, one of five patients with Raynaud’s does not seem to have any underlying disorder (i.e., Raynaud’s disease).

(3) Allen’s Test

10 What is Allen’s test? What does it mean?

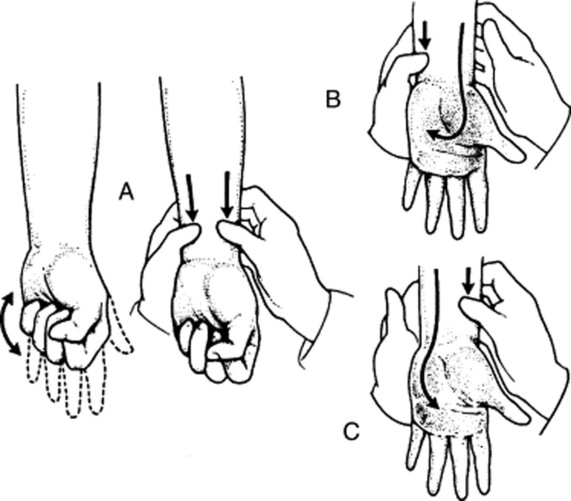

It is a bedside test for patency of the deep palmar arch and of radial/ulnar arteries (Fig. 22-5). Hence, a good way to learn about the risks of radial artery puncture and/or cannulation.

Compress the patient’s radial artery until blood flow is stopped.

Compress the patient’s radial artery until blood flow is stopped.

Have the patient clench and unclench the hand several times in sequence until there is a visible blanching of the hand.

Have the patient clench and unclench the hand several times in sequence until there is a visible blanching of the hand.

When the patient finally relaxes the hand, there will be visible refilling of the capillary bed from the ulnar side, with return of the normal pink color within 5 seconds.

When the patient finally relaxes the hand, there will be visible refilling of the capillary bed from the ulnar side, with return of the normal pink color within 5 seconds.

Absence of refilling (the pallor persists in spite of the hand’s relaxation) or delay in refilling (return of the color takes longer than 5 seconds) indicates a positive test. This reflects occlusion of either the ulnar artery or the deep palmar arch.

Absence of refilling (the pallor persists in spite of the hand’s relaxation) or delay in refilling (return of the color takes longer than 5 seconds) indicates a positive test. This reflects occlusion of either the ulnar artery or the deep palmar arch.

Repeat the maneuver on the contralateral hand, comparing size of the refill area and length of refill time.

Repeat the maneuver on the contralateral hand, comparing size of the refill area and length of refill time.

Finally, repeat the entire sequence, but this time compress the ulnar arteries, first on the right and then on the left.

Finally, repeat the entire sequence, but this time compress the ulnar arteries, first on the right and then on the left.

11 Isn’t the test conducted by simultaneously compressing the ulnar and radial arteries?

Yes, it may be. This is, in fact, a variant of the Allen’s test, conducted as follows (see Fig. 22–5):

Compress both the radial and ulnar arteries.

Compress both the radial and ulnar arteries.

Ask the patient to sequentially and vigorously clench/unclench the hand, so as to squeeze all blood out. When the palm finally blanches, ask the patient to relax the hand.

Ask the patient to sequentially and vigorously clench/unclench the hand, so as to squeeze all blood out. When the palm finally blanches, ask the patient to relax the hand.

Release pressure only on the ulnar artery, and measure the time it takes for the palm to regain its color. This is the refill time for the ulnar artery.

Release pressure only on the ulnar artery, and measure the time it takes for the palm to regain its color. This is the refill time for the ulnar artery.

If refill is delayed or absent (see question 12), do not attempt a radial puncture, but consider instead either a brachial stick or an arterial puncture on the contralateral hand (after similarly checking the arterial supply, of course).

If refill is delayed or absent (see question 12), do not attempt a radial puncture, but consider instead either a brachial stick or an arterial puncture on the contralateral hand (after similarly checking the arterial supply, of course).

Repeat the test, but this time release pressure on the radial artery only, thus measuring refill time for that vessel only.

Repeat the test, but this time release pressure on the radial artery only, thus measuring refill time for that vessel only.

(4) Peripheral Vascular Disease

14 Can peripheral pulses be absent in normal individuals?

Yes. Dorsalis pedis and tibialis posterior are undetectable in 10% of healthy subjects. Congenital loss of one of the arteries usually leads to compensatory increases in the other. Still, only fewer than 2% of healthy subjects lack both pedal pulses. Hence, this is usually an important clue to the presence of peripheral vascular disease (see question 16).

16 What are the symptoms of PVD?

Mostly symptoms of arterial insufficiency, such as exertional limb weakness, resting limb pain (or paresthesia), and poor healing of sores or ulcerations. The classic symptom, however, is claudication (from the Latin term for limping)—i.e., intermittent limb pain, usually triggered by activity. This affects different parts of the lower extremity, depending on which artery is compromised. Yet, whether obstruction is high or low, both pedal pulses are absent in PVD, an important diagnostic clue (see Table 22-1).

| Above the Knee | Below the Knee |

| PVD of the distal aorta (from below the renal arteries to the common iliacs) will cause claudication of the buttocks, thigh, and calf. It may even compromise erection. Given its high location, all lower extremity pulses will be lost. | Peroneotibial PVD will cause either no symptoms or foot claudication. Only pedal pulses are lost. Except for patients with diabetes and thromboangiitis obliterans, this is the least common form of the disease. |

| Femoropopliteal | |

| PVD will cause calf claudication. Femoral pulses are present, but those beyond are absent. |

18 Can these findings predict severity of the disease?

No. Vascular bruits and other signs only indicate presence of disease; they do not correlate with severity. For severity, the standard assessment is the ankle-to-arm systolic pressure index (see Chapter 2, questions 117–119). Still, in diabetic patients with significantly abnormal ankle–brachial indexes, the following symptoms/signs predict more severe disease: (1) age greater than 65, (2) history of peripheral vascular disease or claudication in less than one block, (3) diminished foot pulses, and (4) venous filling time longer than 20 seconds.

19 What is an increased venous filling time?

It is the abnormally slow (re)filling of foot veins in peripheral vascular disease. To test for it:

1. Ask the patient to lie supine.

2. Identify a prominent vein on top of the foot, and then empty it by raising the patient’s leg to 45 degrees for 1 minute.

3. Ask the patient to sit up and lower the foot over the edge of the examining table.

4. Measure how many seconds it takes the vein to become turgid and visible again. Refill time >20 seconds is abnormal.

20 What is a capillary refill time (CRT)?

A generally accepted bedside method for assessing peripheral perfusion. To test for it:

1. Compress the patient’s skin for 5 seconds (usually over a digit—in cases of the lower extremity, compress the plantar skin of the distal great toe) and with sufficient pressure to cause blanching.

2. Release compression, and measure the time in seconds for the compressed area to regain the color of the surrounding skin. More than 2 seconds for the upper extremities (and 5 seconds for the great toe) are considered abnormal.

21 What is the Buerger’s test?

Another bedside maneuver for assessing arterial perfusion to the leg. It consists of examining the color of the patient’s leg: first when elevated and then when lowered. Hence, it consists of two stages (Table 22-2). The test is considered positive for PVD when it elicits excessive pallor with elevation and intense rubor with dependency.

| Stage I | Stage II |

|---|---|

| 1. Ask the patient to lie supine. | 1. Then ask the patient to sit up, and lower the leg over the edge of the examining table—also at an angle of 90 degrees, and also for 2 minutes. |

| 2. Elevate both legs to an angle of 90 degrees, and hold them up for 2 minutes. | 2. Gravity aids blood flow, so that color eventually returns to the ischemic leg, although the skin usually turns blue first (as blood is deoxygenated in its passage through the ischemic tissue), and then finally acquires a dusky red flush that spreads proximally from the toes as the post-hypoxic vasodilation takes place. |

| 3. Observe the feet. Pallor indicates ischemia (i.e., the inability of peripheral arterial pressure to overcome gravity). | 3. Examine both legs simultaneously because changes are most obvious when one leg has a normal circulation. |

| 4. The poorer the arterial supply, the less the angle to which the legs have to be raised in order to become pale (this was what Buerger originally described as the “angle of circulatory sufficiency”). |

23 Is there any finding that argues against the presence of PVD?

Bilateral presence of pedal pulses. Still, beware that as many as one third of PVD patients may have palpable pedal pulses (see question 25).

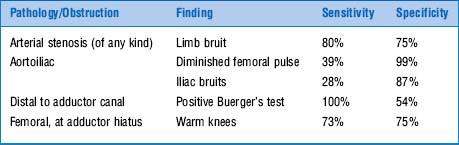

24 How accurate is physical examination for diagnosing the distribution of PVD?

Quite accurate. More specifically, findings can predict different levels of obstruction (Table 22-3). Thus, abnormal pedal pulses, a femoral arterial bruit, prolonged venous filling time, and a unilateral cool limb predict the presence of vascular disease. Abnormal femoral pulse, iliac bruits, limb bruit, Buerger’s test, and warm knees predict instead its distribution. Moreover:

Normal femoral pulses at the level of the inguinal ligament and diminished or absent pulses distally suggest infrainguinal disease alone.

Normal femoral pulses at the level of the inguinal ligament and diminished or absent pulses distally suggest infrainguinal disease alone.

Loss of femoral pulse just below the inguinal ligament suggests a proximal superficial femoral artery occlusion.

Loss of femoral pulse just below the inguinal ligament suggests a proximal superficial femoral artery occlusion.

Loss of popliteal pulse suggests superficial femoral artery occlusion, typically in the adductor canal.

Loss of popliteal pulse suggests superficial femoral artery occlusion, typically in the adductor canal.

Loss of pedal pulses is characteristic of disease of the distal popliteal artery or its trifurcation.

Loss of pedal pulses is characteristic of disease of the distal popliteal artery or its trifurcation.

25 What are the limitations of physical exam in evaluating PVD?

30% of diseased arteries may be palpable. Yet pulses disappear with exercise.

30% of diseased arteries may be palpable. Yet pulses disappear with exercise.

Patent arteries may occasionally be nonpalpable. Yet although the dorsalis pedis may be undetectable in 10% of children, the tibialis posterior is absent in only 0.2% of subjects age 0–19. Hence, lack of both pedal pulses is a good predictor of PVD.

Patent arteries may occasionally be nonpalpable. Yet although the dorsalis pedis may be undetectable in 10% of children, the tibialis posterior is absent in only 0.2% of subjects age 0–19. Hence, lack of both pedal pulses is a good predictor of PVD.

Diabetics may have arteries too stiff to compress, resulting in elevated AASPI.

Diabetics may have arteries too stiff to compress, resulting in elevated AASPI.

(5) Diabetic Foot

28 How common is peripheral neuropathy in diabetics?

Very common. Prevalence is 25% after 10 years of disease and 50% after 20 years.

36 What is the role of physical exam in a diabetic ulcer?

In addition to being comprehensive (diabetes is, after all, a systemic disease), the exam should:

37 Where is a diabetic foot ulcer located?

It is typically located over one of the following sites:

Weight-bearing areas (75% of all ulcers). These include the plantar surface of the metatarsal heads, tips of most prominent toes (usually the first or second), and tips of hammer toes. Heels and malleoli also may be affected as a result of recurrent trauma.

Weight-bearing areas (75% of all ulcers). These include the plantar surface of the metatarsal heads, tips of most prominent toes (usually the first or second), and tips of hammer toes. Heels and malleoli also may be affected as a result of recurrent trauma.

Stress-bearing areas, such as the dorsal portion of hammer toes

Stress-bearing areas, such as the dorsal portion of hammer toes

Other findings of the diabetic foot include (1) hypertrophic calluses, especially over pressure points such as the heel, (2) brittle nails, (3) hammer toes, and (4) fissures.

C. The Peripheral Veins

(1) Edema

41 What is edema of an extremity?

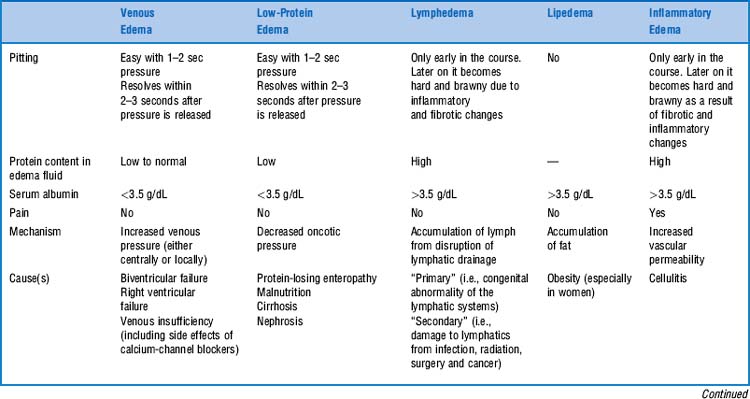

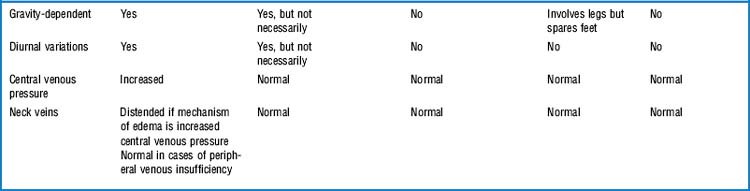

It is the swelling of a limb caused by accumulation of fluid. This could be serum (venous edema), lymph (lymphedema), or fat (lipedema, see Table 22-4).

(2) Venous Insufficiency

49 What is the Trendelenburg’s test?

1. Raise the leg of a supine patient above the level of the heart, until the veins are completely empty and collapsed.

2. Apply a tourniquet to the mid-thigh, thereby compressing the greater saphenous vein and preventing it from draining blood.

3. Ask the patient to stand up, and closely observe the leg veins. In normal subjects, the greater saphenous vein will slowly refill from below the obstruction. This takes less than 1 minute and is due to unimpeded arterial flow in the face of obstructed venous drainage.

50 How do you interpret the test?

If the greater saphenous vein refills rapidly before the tourniquet is released, this indicates backfilling from incompetent valves of the communicating veins.

If the greater saphenous vein refills rapidly before the tourniquet is released, this indicates backfilling from incompetent valves of the communicating veins.

If the greater saphenous vein refills rapidly after the tourniquet is released, this indicates backfilling from incompetent valves of the greater saphenous vein itself.

If the greater saphenous vein refills rapidly after the tourniquet is released, this indicates backfilling from incompetent valves of the greater saphenous vein itself.

Patients with arterial insufficiency may have a false negative test.

Patients with arterial insufficiency may have a false negative test.

54 Who was Trendelenburg?

Friedrich Trendelenburg (1844–1924) was the son of a well-known German philosopher. After studying in Glasgow and Edinburgh, he taught vascular surgery in his native Berlin, and then Rostok, Bonn, and, ultimately, Leipzig, where he stayed as surgeon-in-chief until retiring in 1911. An innovator in his field and the founder of the German Surgical Society, Trendelenburg developed the position that still carries his name in order to operate on the pelvis. He experimented, however, in many other areas. For example, he devised a new surgery for varicose veins—hence, the aforementioned Trendelenburg’s test(s). He even attempted a pulmonary embolectomy in 1907, yet the first successful embolectomy was not performed until 1924, by one of his former students, Dr. Martin Kirshner (1924 also was the year of Trendelenburg’s death, of carcinoma of the mandible). His many interests included a passion for medical history, which prompted him to write a book on ancient Indian surgery, and even an autobiography. Trendelenburg’s name is linked not only to the test(s) and position, but also to the eponymous sign and gait (see Chapter 21, questions 176–179).

55 What is Perthes’ test?

If the veins below the tourniquet collapse as a result of walking, then the deep venous system is patent, and the valves of the communicating veins are competent.

If the veins below the tourniquet collapse as a result of walking, then the deep venous system is patent, and the valves of the communicating veins are competent.

If the veins below the tourniquet remain unchanged, then the valves of both the saphenous veins, and the communicating veins are incompetent.

If the veins below the tourniquet remain unchanged, then the valves of both the saphenous veins, and the communicating veins are incompetent.

If the veins below the tourniquet get more engorged (and the patient experiences leg pain), then the deep venous system is occluded, and the communicating veins are incompetent.

If the veins below the tourniquet get more engorged (and the patient experiences leg pain), then the deep venous system is occluded, and the communicating veins are incompetent.

(3) Deep Venous Thrombosis

57 What is the role of physical exam for diagnosing DVT?

It is part of a comprehensive approach, including review of risk factors and symptoms.

Commonly reported symptoms in suspected DVT include leg pain and swelling.

Commonly reported symptoms in suspected DVT include leg pain and swelling.

Risk factors include instead immobility, paralysis, recent surgery, and/or trauma, malignancy, cancer chemotherapy, advancing age (i.e., >60 years), family history of thromboembolism, pregnancy, and estrogen use. In 50% of DVT patients, a major risk factor is present. Some of these are major, whereas others are minor. These can then be used to calculate the likelihood of disease (Table 22-5).

Risk factors include instead immobility, paralysis, recent surgery, and/or trauma, malignancy, cancer chemotherapy, advancing age (i.e., >60 years), family history of thromboembolism, pregnancy, and estrogen use. In 50% of DVT patients, a major risk factor is present. Some of these are major, whereas others are minor. These can then be used to calculate the likelihood of disease (Table 22-5).

| Major Criteria |

Active cancer (ongoing treatment, treatment within previous 6 months. or palliative treatment) Active cancer (ongoing treatment, treatment within previous 6 months. or palliative treatment) |

Paralysis, bedridden >3 days, and/or major surgery within 4 weeks Paralysis, bedridden >3 days, and/or major surgery within 4 weeks |

Localized tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system in the calf or thigh Localized tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system in the calf or thigh |

Thigh and calf swelling (should be measured) Thigh and calf swelling (should be measured) |

Calf swelling by >3 cm compared with asymptomatic leg (as measured 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity) Calf swelling by >3 cm compared with asymptomatic leg (as measured 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity) |

Strong family history of DVT (>2 first-degree relatives with history of DVT) Strong family history of DVT (>2 first-degree relatives with history of DVT) |

| Minor Criteria |

History of recent trauma (to symptomatic leg within 60 days or less) History of recent trauma (to symptomatic leg within 60 days or less) |

Pitting edema in symptomatic leg only Pitting edema in symptomatic leg only |

Dilated superficial veins (nonvaricose) in symptomatic leg only Dilated superficial veins (nonvaricose) in symptomatic leg only |

Hospitalization within previous 6 months Hospitalization within previous 6 months |

Erythema Erythema |

| Scoring Method |

High probability: three or more major criteria with no alternative diagnosis, two or more major and two or more minor criteria with no alternative diagnosis High probability: three or more major criteria with no alternative diagnosis, two or more major and two or more minor criteria with no alternative diagnosis |

Low probability: one major criterion and two or more minor criteria with alternative diagnosis; one major criterion and one or more minor criteria with no alternative diagnosis; no major criteria and three or more minor criteria with alternative diagnosis; no major and two or more minor criteria with no alternative diagnosis Low probability: one major criterion and two or more minor criteria with alternative diagnosis; one major criterion and one or more minor criteria with no alternative diagnosis; no major criteria and three or more minor criteria with alternative diagnosis; no major and two or more minor criteria with no alternative diagnosis |

Moderate probability: All other combinations Moderate probability: All other combinations |

(Adapted from Anand S, Wells P, Hunt D, et al: Does this patient have deep vein thrombosis? JAMA 279:1094–1099, 1998.)

1 Allen EV, Hines EA. Lipedema of the legs: A syndrome characterized by fat legs and orthostatic edema. Proc Mayo Clin. 1940;15:184-187.

2 Anand S, Wells P, Hunt D, et al. Does this patient have deep vein thrombosis? JAMA. 1998;279:1094-1099.

3 Baker WH, String ST, Hayes AC, et al. Diagnosis of peripheral occlusive disease: Comparison of clinical evaluation and noninvasive laboratory. Arch Surg. 1978;113:1308-1310.

4 Birke JA, Sims DS. Plantar sensory threshold in the ulcerative foot. Leprosy Review. 1986;57:261-267.

5 Blankfield RP, Finkelhor RS, Alexander JJ, et al. Etiology and diagnosis of bilateral leg edema in primary care. Ann J Med. 1998;105:192-197.

6 Carter SA. Response of ankle systolic pressure to leg exercise in mild or questionable arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:578-582.

7 Carter SA. Arterial auscultation in peripheral vascular disease. JAMA. 1981;246:1682-1686.

8 Christensen JH, Freundlich M, Jacobsen BA, et al. Clinical relevance of pedal pulse palpation in patients suspected of peripheral arterial insufficiency. J Intern Med. 1989;226:95-99.

9 Cranley JJ, Canos AJ, Sull WI. The diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis: Fallibility of clinical signs. Arch Surg. 1976;111:34-36.

10 Criado E, Burnham CB. Predictive value of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Surgery. 1997;122:578-583.

11 Criqui MH, Fronek A, Klauber MR, et al. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of traditional clinical evaluation of peripheral arterial disease: Results from noninvasive testing in defined population. Circulation. 1985;71:516-522.

12 DeWeese JA. Pedal pulses disappearing with exercise: A test for intermittent claudication. N Engl J Med. 1960;262:1214-1217.

13 Hall S, Littlejohn GO, Brand C, et al. The painful swollen calf: A comparative evaluation of four investigative techniques. Med J Austr. 1986;144:356-358.

14 Henry JA, Altmann P. Assessment of hypoproteinaemic oedema: A simple physical sign. Br Med J. 1978;1:890-891.

15 Homans J. Exploration and division of the femoral and iliac veins in the treatment of thrombophlebitis of the leg. N Engl J Med. 1941;224:179-186.

16 Insall RL, Davies RJ, Prout WG. Significance of Buerger’s test in the assessment of lower limb ischaemia. J R Soc Med. 1989;82:729-731.

17 Katz RS, Zizic TM, Arnold WP, et al. The pseudothrombophlebitis syndrome. Medicine. 1977;56:151-164.

18 Kraag G, Thevathasan EM, Gordon DA, et al. The hemorrhagic crescent sign of acute synovial rupture. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:477-478.

19 Landefeld CS, McGuire E, Cohen AM. Clinical findings associated with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis: A basis for quantifying clinical judgment. Am J Med. 1990;88:382-388.

20 Lee S, Kim H, Choi S, et al. Clinical usefulness of the two-site Semmes-Weinstein monofilament test for detecting diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Kor Med Sci. 2003;18:103-107.

21 McGee S, Boyko EL. Physical examination and chronic lower-extremity ischemia: A critical review. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1357-1364.

22 McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, et al. The independent contributions of diabetic neuropathy and vasculopathy in foot ulceration. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:216-219.

23 Molloy W, English J, O’Dwyer R, et al. Clinical findings in the diagnosis of proximal deep vein thrombosis. Ir Med. 1982;175:119-120.

24 Mueller MI. Identifying patients with diabetes mellitus who are at risk for lower-extremity complications: Use of Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments. Phys Ther. 1996;76:68-71.

25 Parfrey N, Ryan JF, Shanahan L, et al. Hairless lower limbs and occlusive arterial disease. Lancet. 1976;1:276.

26 Robertson GSM, Ristic CD, Bullen BR. The incidence of congenitally absent foot pulses. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72:99-100.

27 Silverman JJ. The incidence of palpable dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulsations in soldiers: An analysis of over 1000 infantry soldiers. Am Heart J. 1946;32:82-87.

28 Stein PD, Henry JW, Gopalakrishnan D, et al. Asymmetry of calves in the assessment of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Chest. 1995;107:936-939.

29 Valk GD, Nauta JJ, Strijers RL, et al. Clinical examination versus neurophysiological examination in the diagnosis of diabetic polyneuropathy. Diab Med. 1992;9:716-721.