Chapter 2 The evolution of pharmacy practice

INTRODUCTION

The practice of pharmacy in Australia has changed over recent years from a traditional focus on the product to a greater emphasis on the patient and the provision of pharmaceutical care. The International Pharmaceutical Federation (also known by the French term Federation Internationale Pharmaceutique, hence being abbreviated as FIP) has defined pharmaceutical care as ‘…the responsible provision of pharmacotherapy for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes to improve or maintain a patient’s quality of life…’.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has also recognised the pharmacist’s role in the provision of pharmaceutical care services in their handbook Developing pharmacy practice[2]

As readily accessible health professionals, pharmacists provide primary health care including education and advice to promote good health and to reduce the incidence of illness.

A sound pharmaceutical knowledge base, effective problem solving, organisational, communication and interpersonal skills, together with an ethical and professional attitude, are essential to the practice of pharmacy.[3]

General characteristics required of pharmacists were also identified by the WHO through the concept of the ‘seven-star pharmacist’, and involve the roles of caregiver, decision-maker, communicator, manager, life-long learner, teacher and leader.[4]

DEVELOPMENT OF THE STRUCTURE OF THE PROFESSION

The establishment of pharmacy practice in Australia followed the English tradition applicable at the time of the First Fleet. Pharmacists had no recognised role or status and had to compete with medical practitioners, grocers and retailers.[5]

Australia’s first ‘pharmacist’, John Tawell, arrived in 1815 as a convict and opened his business in 1820, a combination of grocery and dispensary. A specially convened medical board certified him fit to ‘compound and dispense’ medicines.[5]

The practice of pharmacy in the colonies was casual and no qualifications were necessary and activities were not regulated.[5]

Tawell returned to England in 1840 and he was later hanged for poisoning his mistress with a mixture of prussic acid and stout.[6]

The first major legislative controls regulating pharmacy practice were introduced in the latter part of the 19th century. Prior to federation under the Australian Constitution in 1901 most of the six colonies had a licensing system for selling poisons. In order to ensure that the public would be protected from untrained quacks, groups of chemists and druggists got together to establish colonially organised Pharmaceutical Societies.[7] Each new society was modelled on the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (now the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain), and these colonial societies were a powerful influence and exerted a significant force on the development of Australian pharmacy. The societies developed the first written standards in education, qualifications and ethics. They assumed a responsibility to maintain the first schools of pharmacy in Australia.

The societies influenced the development of pharmacy legislation in each colony or state. Pharmacy Acts provided some restrictions regarding titles and right to practise as a chemist. However, the enforcement of the legislation was vested in pharmacy boards following a separation of roles.[7, 8]

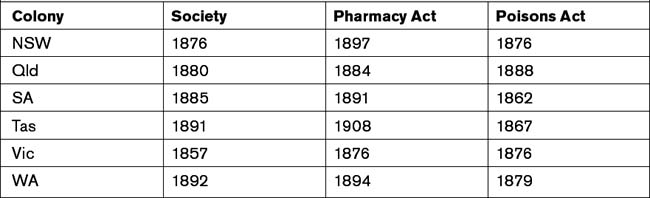

The separation of roles was a departure from British precedent, where the society had the authority to maintain the register, conduct examinations, and discipline pharmacists. The creation of separate bodies, distinct from professional organisations, was intended to keep the boards independent of the organisations and to clearly establish that boards existed for the public good. On the other hand, the society acted on behalf of the profession. Ultimately, this approach was to be followed by all jurisdictions except for Western Australia, which followed the British model in the society having a combined role of being the professional association and the registering authority. Table 2.1 provides a summary of the dates involved in the foundation of the societies and the promulgation of the first legislation.[7]

The first Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary Handbook was published in 1902 with a range of formulae for non-official formulations.[9] Other pharmacopoeias (Greek pharmakon, a drug and poieo, I make) still being referred to in drugs and poisons legislation include the British Pharmacopoeia (BP), the British Pharmaceutical Codex (BPC) and the Extra Pharmacopoeia (Martindale).

Pharmaceutical Defence Limited (PDL) was formed following a court case against a chemist, Francis Gough, who was sued for damages by a farmer, William Hilton, following an alleged poisoning in 1911. The farmer won the case and Gough had to pay damages. Chemists recognised their vulnerability and were alarmed as they realised that any alleged dispensing error, real or not, whether originating with the prescriber or the dispenser, could lead to a chemist being sued.[10] PDL was hence set up to allow chemists to take out insurance against such happening.

NATIONAL MEDICINES POLICY FRAMEWORK

A major review of medication usage and waste by the federal government Department of Health and Ageing in the 1990s led to the launch of Australia’s National Medicines Policy (NMP) in 2000. The overall aim of this policy is to meet medication and related service needs through achieving both optimal health outcomes and economic objectives.[11] The policy is based on four objectives, namely:

Australia’s National Strategy for QUM was released in 2002 to complement the NMP, and specifically details the range of partnerships and activities to improve QUM.[12] The strategy lists the key partners in achieving QUM, which include prescribers and providers of medicines. In fulfilling both these roles, pharmacists are crucial to the achievement of QUM. The strategy places a specific obligation on pharmacists, as health practitioners and educators, to:

Pharmacy education

Until the 1960s, pharmacy training in Australia was based on an apprenticeship where students spent part of their time at a tertiary institution and the remainder working under supervision of a ‘master’ pharmacist. In the early 1960s full-time degree standard courses were introduced throughout Australia.[2, 5]

In the late 1990s the undergraduate pharmacy degree courses were extended from three to four years. This followed a House of Representatives Standing Committee on Community Affairs inquiry in 1992.[13] Additionally, university courses have also changed significantly over the last two decades with regard to context and level of expertise required to prepare students for the evolving role of pharmacists. Pharmacy schools offer either an undergraduate degree (BPharm), which is completed over four years, or a post-graduate degree (MPharm), which in many cases may be completed in less than four years. University education aims to enable graduates to provide patient-focused services with students being exposed to actual pharmacy practice through placement programs. These placements are a mandatory requirement for program accreditation by the New Zealand and Australian Pharmacy Schools Accrediting Committee (NAPSAC) and form a significant component of the various pharmacy education programs.

In order to be eligible for registration as a pharmacist with the relevant state or territory pharmacy registering authority, a 12-month internship in a pharmacy must be completed following graduation, although there are some minor interstate variations in the period of the internship.[14] During the period, interns undergo continuous assessment based on the competency standards developed by the PSA, and are also required to undertake the Australian Pharmacy Competency Assessment Tool (APCAT), a standardised assessment developed by the Australian Pharmacy Council (APC) and conducted throughout Australia.

Competency is defined by the PSA as the ‘skills, attitudes and other attributes attained by an individual based on knowledge and experience which together are considered sufficient to enable the individual to practise as a pharmacist’.[3] The PSA Competency Standards consist of the following eight functional areas:

The Competency Standards are used by APC through NAPSAC to evaluate and accredit new and existing pharmacy schools and their educational programs. The Australian Pharmacy Examining Committee (APEC), a standing committee of the APC, oversees the registration of overseas-trained pharmacists. All overseas-trained pharmacists are required to be assessed for competency to practise in Australia through a formal process, which ensures national consistency in the assessment and registration of overseas-trained pharmacists.[15]

Consistent with the development of international pharmacy practice, and in response to the Wilkinson Review recommendations and national trends in other health professions, mandatory continuous professional development programs have been developed or are being developed in most states.[16] Continuing professional education is most often carried out by the professional pharmacy organisations and, to a lesser extent, by some of the universities. Additionally, the National Prescribing Service (NPS), which is an independent, non-profit organisation providing medicines information and resources for consumers and health professionals, offers multi-professional education activities with a quality use of medicines focus.

PHARMACY SECTORS

Community pharmacy

Community pharmacists are the most accessible health care professionals in the Australian health care system as clients do not routinely have to make an appointment to receive professional attention. They are often the first health professional to be approached by patients or carers. Additionally, as those patients on medication for chronic conditions have their prescriptions filled on a regular basis (often monthly) they may have more contact with their pharmacist than with their doctor. Thus, the pharmacist is ideally placed to play a pivotal role in disseminating health information and managing medication-related issues.

One of the issues that community pharmacists have to face is the tension that exists between retail activities, the provision of professional services and the perception of the extent to which one may influence the other. This dichotomy differentiates community pharmacy practice from other primary health care providers.[17] However, the division between the provision of professional services and the selling of products is yet to be resolved as many community pharmacists balance demands of sensible financial management with professional practice.[18]

Hospital pharmacy

There are two main aspects to hospital pharmacy practice. First are those activities relating to the dispensing, supply and distribution of medicines, including the aseptic preparation of cancer chemotherapy and other products requiring sterile preparation. In addition, many hospital pharmacies offer formulation services to facilitate the preparation of oral liquid preparations for children; for example, where there is no commercially available product.[19]

An ongoing challenge for pharmacists in both the community and hospital practice settings is to address the problems of medication management as health consumers move from one episode of care to another, as characterised by the hospital/community interface. To assist with the development of systems to improve the continuity in medication management between different health care settings, APAC developed the following 10 Guiding principles to achieve continuity in medication management:[20]

FUTURE ROLES FOR PHARMACISTS

Wider prescribing rights for pharmacists are being considered and various prescribing models are currently being trialled, including admission prescribing in hospitals and continued prescribing in aged care facilities.[21] This trend is following the pattern in other countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States of America.[22, 23] These prescribing models vary. In some instances pharmacists need to follow strict protocols and may only supplement what has already been prescribed by a doctor.[24] However, in other instances, pharmacists with specified training may carry out independent prescribing. Not surprisingly, concerns have been raised by the medical profession with regard to pharmacist prescribing. These concerns include the lack of pharmacist access to medical records, accountability and compromised patient safety in not separating prescribing and dispensing. Although research has shown some pharmacists may be reluctant to take up these new roles, many others are enthusiastic about the opportunity to provide these extended services.[22]

It is worth noting that United Kingdom legal experts have commented that these new prescribing rights bring new responsibilities. Pharmacists will have to accept a higher level of legal responsibility in cases of prescribing errors, similar to that of doctors;[24] with new rights and responsibilities comes changed legal liability.

ACCREDITATION OF PHARMACY SERVICES

The Quality Care Pharmacy Program (QCPP) was developed with government funding under the first Community Pharmacy Agreement. It has been an important self-regulating vehicle for driving and implementing change management within community pharmacy. It is the tool through which the PGA has facilitated the improvement of quality services within community pharmacy. The QCPP has support from the PDL which provides specialised indemnity insurance for the pharmacy profession. PDL has indicated that a court would probably consider a pharmacy’s accreditation status in the case of an error.[25]

QCPP is a tool available to community pharmacists for standardising the provision of pharmaceutical services. As stated by the PGA in a response to the Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care Discussion Paper — National Safety and Quality Accreditation Standards (November 2006), it has been developed by community pharmacy, for community pharmacy.[26] Therefore, to some extent, the PGA dictates the minimum standard of community pharmacy practice through the program.

Department of Health and Ageing. National Medicines Policy. In: Ageing DoHa. Department of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia; 1999–2000:1-7.

The national strategy for quality use of medicines. Department of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia, 2002. 1–36

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Competency standards for pharmacists in Australia. Deakin, ACT: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, 2003.

Pharmacy Guild of Australia (PGA) Quality care pharmacy program. 2006. Online. Available: http://beta.guild.org.au/qcpp/ [accessed 27 May 2009]

Wiedenmayer K., Summers R.S., Mackie C.A., Gous A.G.S., Everard M. Developing pharmacy practice: a focus on patient care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006.

1 International Pharmaceutical Federation. FIP Statement of Professional Standards: Pharmaceutical Care. The Hague, The Netherlands, 1998. Online. Available. www.fip.org/www/uploads/database_file.php?id=269&table_id= [accessed 26 November 2008]

2 Wiedenmayer K., Summers R.S., Mackie C.A., Gous A.G.S., Everard M. Developing pharmacy practice: a focus on patient care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006.

3 Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Competency standards for pharmacists in Australia. Deakin, ACT: Pharmaceutical Society of Australia; 2003.

4 World Health Organization (WHO). The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. Preparing the future pharmacist: curricular development. Vancouver, Canada: WHO; August 1997. 27-29

5 The Pharmacy Guild of Australia (PGA). Pharmacy in Australia. 1988: 13

6 Senator Jan McLucas in a speech representing the Minister for health and Ageing, Australian Pharmacy Guild Conference, Gold Coast, Queensland, 28 March 2008

7 Haines G. Pharmacy in Australia: the national experience. Sydney: Australian Pharmaceutical Publishing Company Ltd; 1988.

8 Bomford J., Newgreen D.B. The Pharmacy Board of Victoria: a history 1877–2005. Burwood, Victoria: BPA Print Group Pty Ltd; 2005.

9 Chapter 6 from A Scandalously short introduction to the history of pharmacy. Online. Available: www.psa.org.au [accessed 27 May 2009]

10 Greenwood S. Ready prepared! The history of the Pharmacy Guild of Australia from 1928 to 2008. Australian Pharmaceutical Publishing Co Ltd; 2008. 15

11 Department of Health and Ageing. National Medicines Policy. In: Ageing DoHa. Commonwealth of Australia; 1999–2000:1-7.

12 Department of Health and Ageing. The national strategy for quality use of medicines. Department of Health and Ageing. 2002:1-36.

13 Roller L. The historical development of a contemporary pharmacy course in Victoria. Australian Pharmacist. September 1999;18(9):553-558.

14 Hattingh H.L., Smith N.A., Searle J., King M.A., Forrester K. Regulation of the pharmacy profession throughout Australia. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research. 2007;37(3):174-177.

15 Australian Pharmacy Council. Welcome to the Australian Pharmacy Council website. 2008. Online. Available: www.copra.org.au/[accessed 1 February 2008]

16 Wilkinson W.J. National Competition Policy Review of Pharmacy: Report to the Council of Australian Governments. Canberra: Council of Australian Governments; 2000.

17 Benrimoj S., Frommer M.S. Community pharmacy in Australia. Australian Health Review. November 2004;28(2):238-246.

18 Tullett J., Rutter P., Brown D. A longitudinal study of United Kingdom pharmacists’ misdemeanours — trials, tribulations and trends. Pharmacy World & Science. April 2003;25(2):43-51.

19 Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia. What does a hospital pharmacist do? 2008. Online. Available: www.shpa.org.au/pdf/positionstatement/facthos-ppharm.pdf [accessed 24 February 2008]

20 Australian Pharmaceutical Advisory Council. Guiding principles to achieve continuity in medication management. Guidelines. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia; July 2005.

21 Nissen L. Destiny or dream? — Prescribing rights for pharmacists in Australia. Pharmaceutical Journal. February 2007;26(2):130-135.

22 Buckley P., Grime J., Blenkinsopp A. Inter- and intra-professional perspectives on non-medical prescribing in an NHS trust. Pharmaceutical Journal. 30 September 2006;277:394-398.

23 Emmerton L., Marriott J., Bessell T., Nissen L., Dean L. Pharmacists and prescribing rights: review of international developments. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science. 4 August 2005;8(2):217-225.

24 Newdick C. Pharmacist prescribing — new rights, new responsibilities. Pharmaceutical Journal. 4 January 2003;270:25.

25 Pharmaceutical Defence Limited. What are your risks without Quality Care? Australian Journal of Pharmacy. August 2006;87:14.

26 Pharmacy Guild of Australia (PGA). The Pharmacy Guild of Australia response to the Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care Discussion Paper — National Safety and Quality Accreditation Standards. The Pharmacy Guild of Australia, ACT, November 2006