CHAPTER 43 The ethnic rhinoplasty

History

Rhinoplasty, since its origins has been intimately tied to specific ethnicities. For example, John Roe1 used endonasal approaches to perform cosmetic rhinoplasty on the “pug nose” (referring to Irish patients who had excessive nostril show and a high nasolabial angle), while Jacques Joseph, modified tips and dorsal humps in Germany in the early 1900s.2 More recently, there have been numerous articles, documentaries, and media exposure over the popularity of rhinoplasty in Tehran, Iran, which is referred to by popular media as “the capital of nose jobs”.

In the United States, “standards of beauty” propagated by the mass media, are mostly based on Northern European facial traits with well-defined aesthetic goals (straight, narrow bridge, narrow and sharply defined nasal tip, a nasolabial angle of 90 to 95 degrees in men and 95–105 degrees in women). However, refining the nose of ethnic patients does not adhere to these European-based characteristics, which can lead to “racial incongruity”.3

“Racial incongruity” refers to an imbalance between the physical traits of individual and their ethnic background.3 A marked disproportion between nasal and facial morphology can be very conspicuous and awkward. For example, a sharp supra-tip break and an overly narrowed alar base in an African-American patient with Fitzpatrick 6 skin type, large jaws, and thick sebaceous skin, appears unnatural and over-operated. Many of the principles of avoiding an “over-operated” looking nose, are inherent to rhinoplasty as a whole. These concepts are even more critical in ethnic patients and racial incongruity can be prevented through proper preoperative evaluation and precise technical execution.

Many of the rhinoplasty lessons that we have learned and continue to improve upon have been by way of our non-Caucasian patients.1–16 Ethnic patients generally fall into two categories, those who want a “dramatic” difference without close attention to retaining their “ethnic” nose, and those who want subtle, natural refinement, without any loss of ancestral traits. The authors advocate a more “natural” approach to ethnic rhinoplasty. Furthermore, we feel that an open approach rhinoplasty works best for the complex, multidimensional nasal features of ethnic patients.3–9

African-American

Physical evaluation and anatomy

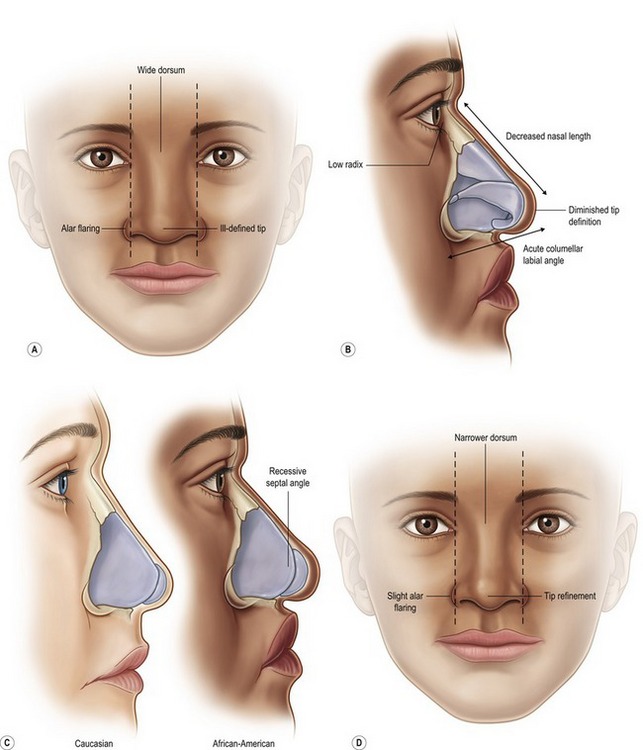

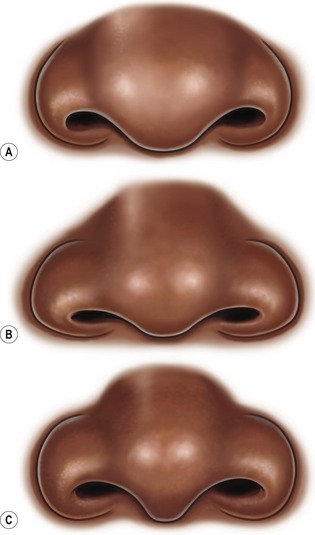

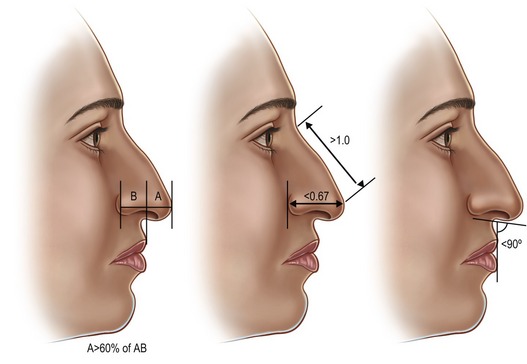

As with all rhinoplasty patients, the objectives should be clearly emphasized and discussed preoperatively. Ofodile and Bokhari5 have described a variable spectrum in anatomical traits of African-Americans depending on their origin. Rees6 observed that West Indies origination may influence the presence of a dorsal hump, which is very rare in African-Americans living in the United States. The African-American nose can typically be characterized by: thick, sebaceous skin/soft tissue, a shorter columella with less tip projection (rarely drooping), wide and flat dorsum (wide or non-distinct dorsal aesthetic lines), retrusive septal angle, alar flaring, wide interalar distance, bulbous tip, round nostrils, short nasal length, wide pyriform aperture, and bimaxillary protrusion (Fig. 43.1). In contradistinction to many Hispanic and Middle Eastern noses, African-American and Asian noses have a retrusive septal angle which can be beneficial in creating a pleasing tip-dorsum differential. Figure 43.2 depicts typical preoperative tip–alar relationships that should be recognized to prevent postoperative aesthetic complications. The osseous pyramid is often retrusive and wide. The presence and magnitude of these morphological traits should be closely evaluated, in addition to standard naso-facial analysis. Rohrich and Muzaffar3 have a clearly outlined and detailed study on African-American patients.

Technical steps

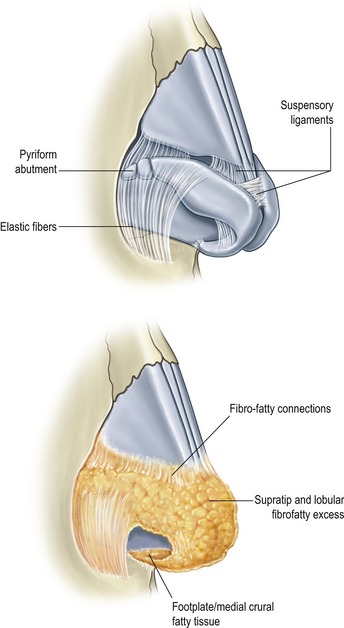

In general, African-American patients, like Asian patients, need augmentation in multiple dimensions. A common characteristic shared in varying degrees by each ethnic group in this chapter, is a thick, amorphous, and sebaceous skin/soft tissue nasal envelope and is best exemplified by the African-American nose. This weighs down the lower lateral, middle and medial crura, which can lead to prolonged swelling. Wide undermining is required for exposure, recruitment of nasal skin, and more even re-distribution of soft tissue healing forces (may aid in reduction of postop notching and buckling). The undersurface of the nasal skin, particularly in the supratip, domal, and paradomal region should be trimmed to, but not past the level of the subdermal plexus. Soft tissue debulking may improve the contractile ability of the skin to reveal the underlying framework established (Fig. 43.3). Taping and massage postoperatively plays an important role in limiting fibrous edema and thickened scarring between the skin and cartilage.

Dorsal aesthetic lines are just as important as tip shaping in African-Americans. The gold standard in dorsal augmentation is rib cartilage; however if the patient does not desire this, or does not require more than 6 mm of augmentation then the following methods can be employed: septal grafting with fascia or Alloderm (LifeCell Corp., Branchburg, NJ) overlay, Surgicel17 or fascia-covered diced cartilage,18 or silicone dorsal implant. We do not advocate the “L-shaped,” combination dorsal-tip projection silicone implant which has a higher extrusion and complication rate.

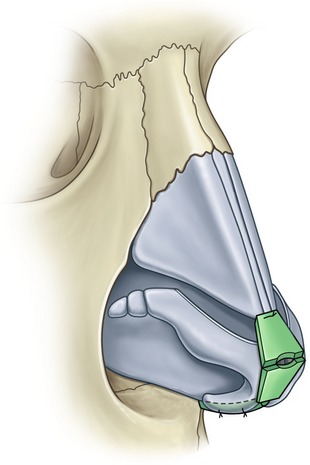

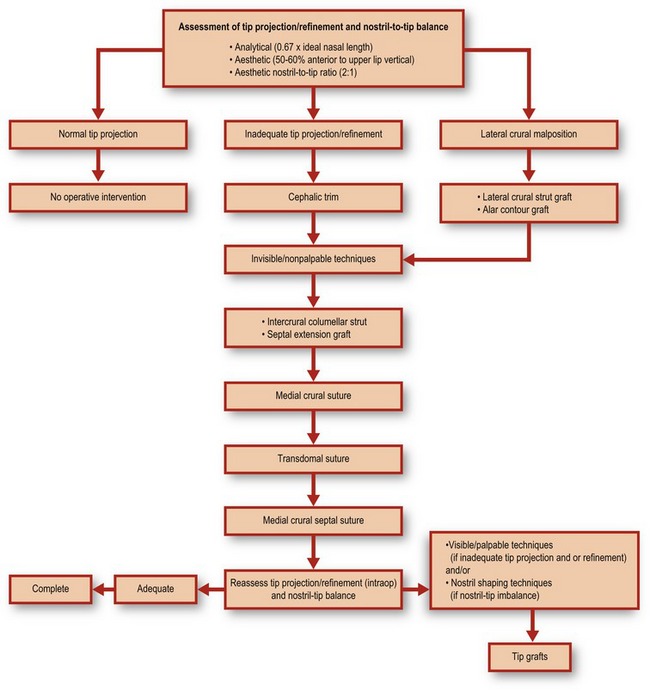

The new cartilaginous frame/shape must be established through maneuvers that increase tip support along with refinement. One benefit of the thick soft tissue coverage is that visible and more aggressive maneuvers can be used to improve tip shape and projection. A combination of tip suturing techniques are usually needed.19–22 A systematic approach is advocated to serve as a guide (Fig. 43.4). This begins with establishing tip platform strength via a columellar strut, medial crural sutures (MCS) and medial crural–septal sutures (MCSS)(if necessary for tip positioning). Transdomal sutures (TDS), interdomal sutures (IDS), and lateral crural spanning sutures (LCSS) are placed next. A helpful technique to improve alar arch strength is to overturn and suture the cephalic portion of the LLC to the native caudal rim strip instead of simple excision, known as a “lateral crural turnover flap”. This is a beneficial maneuver in ethnic patients because irregularities in the lower lateral crura are corrected while simultaneously improving rim support. Alar contour grafts are often needed to prevent notching at the soft triangle which can readily occur in African-American and Asian patients due to round nostril shape, and wide interalar distance that is later reduced. The excess alar soft tissue, when bent and medialized during tip shaping tends to buckle and addition of a crushed soft triangle graft may be needed.

Fig. 43.4 Tip algorithm. This serves as a general guide in performing systematic nasal tip shaping.

Adapted from Janis JE, Ghavami A, Rohrich A. A predictable and algorithmic approach to tip refinement and projection. In: Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Adams WP Jr, eds. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters, 2nd edn. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical, 2007.

Further tip refinement is established with a combined infratip lobular/onlay tip graft (Fig. 43.5). This will augment the deficient infratip lobule, improve tip projection and provide for necessary breakpoints. Septal cartilage is best and suture stabilization of the graft to the columellar construct and domes is recommended. Increased tip augmentation can be achieved by allowing the cephalad portion of the Gunter-type graft to project anterior to the domes. More cartilage grafts can be placed under this cephalad portion or as onlays. Additional crushed graft remnants can be placed after columellar closure, using a Bayonet forcep. Skin redraping throughout the process of tip shaping helps determine the influence of each maneuver on the external surface, which is the ultimate aesthetic goal.

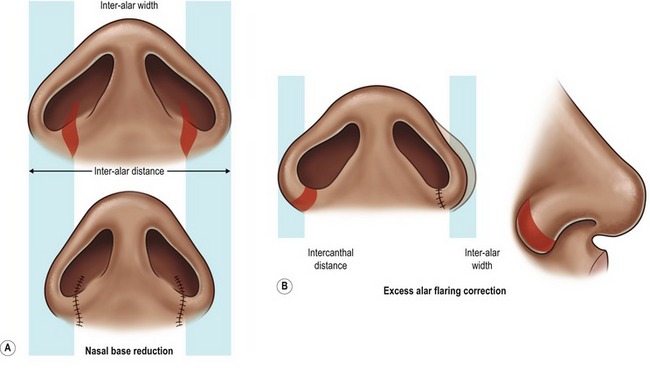

Lastly, enhancement of nostril shape and alar base reduction is almost always needed. Degree of alar flaring should be assessed according to how lateral to the medial canthus the flare is. Alar base resection is required when this is >2 mm (Fig. 43.6). Excision should not extend beyond the supra-alar groove where the lateral nasal artery travels. Closure using the “halving principle” is required. Excision amount should be measured with a caliper, and may be different on each side. Typically this measures between 6–12 mm. Extension into the nostril sill is needed when interalar distance is wide. Postoperative care will be discussed after all the ethnic nasal types have been addressed.

Case 1

African-American

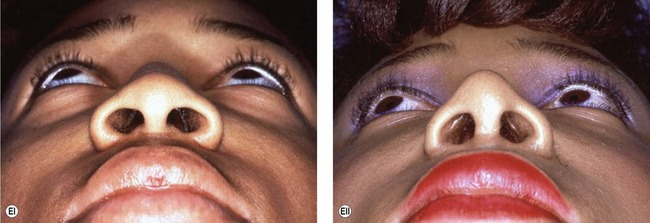

The patient demonstrates a wide dorsal hump and flat, poorly defined nasal tip (Fig. 43.C1). Alar base is wide. She also presents with a hanging ala and weak columella. There is a high dorsal hump and columellar-lobule disproportion. Internal exam was normal.

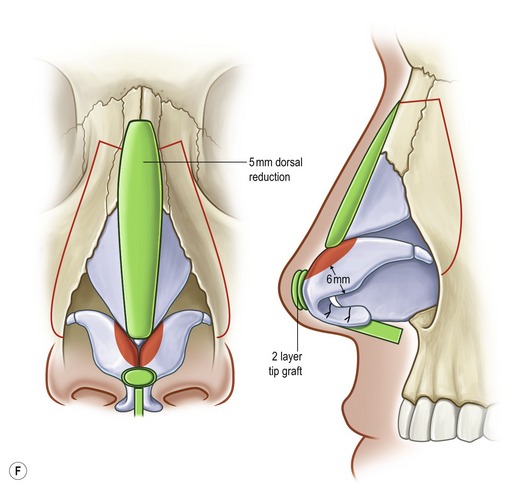

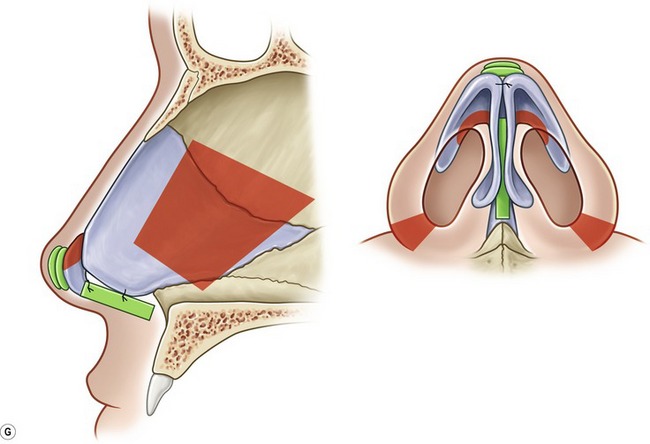

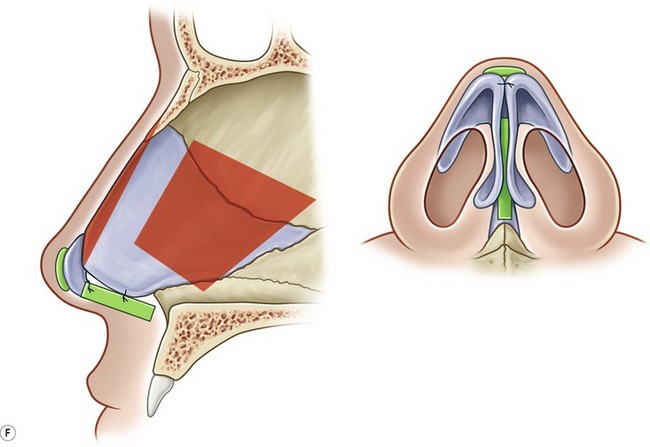

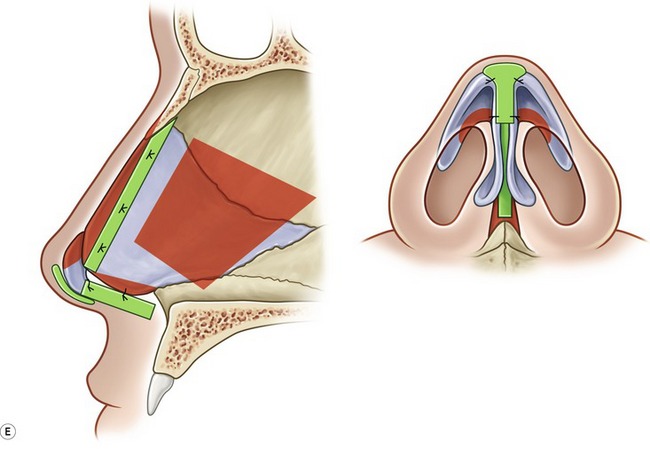

Fig. 43.C1 A, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. B, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. C, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. D, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. E, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. F, Intraoperative technique. G, Intraoperative technique. Red, resection/excision; Green, augmentation/grafts.

Operative steps

• Open approach with stair-step transcolumellar incision joined to bilateral infra-cartilaginous incisions.

• Component reduction of dorsum (5 mm).

• Cephalic resection of lower lateral cartilage, preserving 6 mm rim strips.

• Floating columellar strut graft stabilized to repositioned (more anteriorly projecting) medial crura with polydioxanone sutures.

• Graduated, sequentially-placed transdomal and interdomal “shaping” sutures.

• Onlay tip grafts x3, stabilized with sutures.

Hispanic

Introduction

Hispanics make up the largest proportion of ethnic minority groups in the United States. In areas such as Los Angeles and Miami, Hispanic patients are one of the largest groups seeking cosmetic surgery. Aside from post-partum modifications such as body and breast contouring, rhinoplasty is becoming a more acceptable way to achieve a refined elegance and balance to the face. Similar to Middle Eastern patients, this ethnic group requires detailed preoperative planning to delineate the significant characteristics that warrant alteration. An over-operated appearance is commonly seen by surgeons that perform similar maneuvers in every ethnic type, without regard for the anatomical distinctions. As a whole, Hispanic patients are very appreciative, and realistic about the postoperative expectations.

Physical evaluation and anatomy

A classic Hispanic rhinoplasty study is that of Fernando Ortiz-Monasterio on the Mestizo nose.11 Ortiz-Monasterio11 lists five characteristics that differ from Caucasian noses: (1) thick, sebaceous soft tissue envelope; (2) small osseocartilaginous vault; (3) weak tip support due to short medial crura and weak caudal septum; (4) short, hidden columella; and (5) broad alar base and round nostrils. He advocates an intracartilaginous approach with supportive grafts, struts, minimal dorsal augmentation, and nostril/sill correction. Since that seminal manuscript, further ethnic and morphological delineations have been made by Sanchez23 (“Chata”-Caribbean nose, predominant “Black” or “Asian” features) and Milgrim.24 Milgrim24 divides the Hispanic female nose into three subtypes based on geographical origin: Caribbean, Central American, and South American.

Daniel15 reported on his experience with primarily Mexican-American patients and classified them into three types: Type 1 – (Castilian) high arched osseocartilaginous dorsum and normal tip projection; Type 2 – (Mexican-American) low radix and underprojecting tip with the illusion of a large dorsal hump; Type 3 – (Mestizo) thick skin envelope, dorsal-tip disproportion, amorphous, wide base. While classifications are less relevant, an analysis-based treatment plan is imperative in this ethnic group. In addition, those with more African-American (Caribbean-Creole) features tend to be more wary of significant nasal modification, sometimes citing noses of notable African-American celebrities that display extreme “racial incongruity”.

The bony vault, when wide and excessive, is treated with low-to-low osteotomies (sometimes with a cephalad medially directed J-component),25 while short nasal bones in the “Chata” or Mestizo type nose can be treated with illusory and augmentative grafts. Daniel finds this to be a strong indication for his diced cartilage-temporalis fascia construct.18 However, the nasal bones, even when short are stronger than those of African-American and Asian noses.

We find there to be significant heterogeneity in the cartilaginous-bony relationship in Mexican-American noses. Nevertheless, two general morphologies present: (1) those towards the African-American spectrum with weak, wide, flat cartilage, wide alar base (usually combined with round nostrils), and low/flat dorsum; and (2) and those that present more as Mediterranean/Middle Eastern nasal types with dorsal hump, long nasal bones, poor tip projection and moderate tip bulbosity. When dorsal reduction is indicated, it should be performed in a graduate, component fashion.26 Tip position in both groups usually is not plunging and if so, minimal tip rotation is required. Therefore, the mechanical disadvantage of low tip complex position relative to a high septal angle, (which predominates in the Middle Eastern nose) is not a major issue.

Often the dynamic effects of cephalic trim, tip suturing and a columellar strut is all that is necessary to maintain tip position long term. Suturing the tip complex to the caudal septum, significant caudal septal resection, and anterior nasal spine modification are sometimes required to enhance the columellar–labial relation. However, tip shape is of great importance to Hispanic patients and can proceed in the usual stepwise fashion (Fig. 43.4).

Case 2

Hispanic

This patient demonstrates a Castilian type nose. She has a flat, poorly projecting nasal tip with a small degree of droop (Fig. 43.C2). Nasal skin is thin. There is a dorsal hump and marked alar–columellar disproportion. Caudal deviation and tip asymmetry are also present. The tip is poorly defined. This patient desired a dramatic improvement.

Fig. 43.C2 A, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. B, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. C, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. D, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. E, F Intraoperative technique.

Middle Eastern

Introduction

Middle Eastern patients make a up a large proportion of rhinoplasties performed throughout the world. In Iran, it is even fashionable to walk the streets with a nasal splint and it has become almost a sort of “rite of passage” for both males and females. Middle Eastern patients request rhinoplasty in numerous countries, including the United States. However, one explanation for the dramatic numbers seen in countries such as Iran, may be that the face is often the only visible part of the body in everyday public life (due to religious laws). Middle Eastern nasal characteristics present on a gradient between the African-American nose3–7 and the Caucasian nose.

“Middle Eastern” commonly refers to people of Arabic, Turkish, North African, Semitic (i.e. Assyrian, Judean, Babylonian descent), Armenian, and Persian descent. Further ethnic and geographical delineations are beyond the scope of this chapter. In a review on Middle Eastern rhinoplasty techniques, Bizrah8 simplifies the division of the “Middle Eastern” population into the Middle East, North African, and Gulf regions. He makes a particular distinction as to the aesthetic preferences and social distinctions of specific groups, namely Gulf (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Iran, and Oman) and non-Gulf groups (Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt and Morocco), with non-Gulf patients desiring more tip projection and less dorsal height. A large proportion of Middle Eastern patients are young females who often arrive at their consultation with their mother or mother and father. It is important to include the parents in the consultation and detailed discussion as they are very proactive and involved. It is not uncommon that the mother initiates the entire process.

Rohrich and Ghavami9 present a component-driven approach based on specific classic nasal traits (Fig. 43.7 and Table 43.1). The goals in Middle Eastern rhinoplasty are shown in Table 43.2.

Table 43.1 Common characteristics of the Middle Eastern nose*

* Percentage frequencies are listed in parenthesis. The total number of patients is 71.

† Crural morphology was observed intraoperatively and was not quantified.

Adapted from: Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A. Rhinoplasty for the Middle Eastern nose. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;123(4):in press.

Table 43.2 Common goals in Middle Eastern rhinoplasty

Adapted from: Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A. Rhinoplasty for the Middle Eastern nose. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;123(4):in press.

Physical evaluation and anatomy

Similar to African-American patients, the weak cartilaginous framework is over-burdened by a heavy infiltration of fibro-fatty tissue in the supratip, inter-domal space, paradomal region, and between the medial crura. Debulking of soft tissue should not violate the subdermal plexus as irregularities and vascular embarrassment may result. Furthermore, the skin/soft tissue envelope can be thin in certain areas (infratip) and overall thinner than Mestizo, Asian, and African-American counterparts, mandating the use of less “visible” and crushed cartilage grafts. However, grafts are important in Middle Eastern noses, in order to fill the skin envelope dead space after reductive maneuvers, and to shape the tip with added finesse. These patients can be very judgmental and detailed in their postoperative analysis of the surgeon’s work, with attention even to the basilar view.

Commonly, the nasal dorsum is wide with a significant hump. The width begins very low at the ascending process of the maxilla. The nasal bones are almost always long which allows for the creation of dorsal aesthetic lines in a more predictable and precise manner. Osteotomies, if done, are performed using a low-to-low percutaneous technique or, if desired, a low-to-low internal continuous technique. A graduated dorsal hump reduction is important in order to directly visualize the magnitude of dorsal reduction attained in an incremental fashion.26 This prevents excessive dorsal reduction, and subsequent problems such as inverted V-deformities which are all too common in Middle Eastern patients presenting for revision. Use of Byrd’s “autospreader flap” is beneficial to preserve more septal cartilage for other uses.27 This is an extremely versatile, easy and useful technique and obviates the requirements for traditional spreader grafts in most cases. It is an important tool in large dorsal reduction.

The lower lateral and medial crural cartilages are frequently weak relative to the heavy skin and soft tissue overlying them. Furthermore they are frequently malpositioned (Fig. 43.8), which complicates the balance between the tip shape and alar arch. The lateral crura may be wide, but commonly do not contribute substantially to overall alar arch strength when they are malpositioned in a cephalad direction. When lateral crural malposition cannot be camouflaged with cephalic trim alone, then transection at the accessory chain region along with caudal repositioning using a lateral crural strut28 or alar contour graft is performed. Toriumi29 places importance on the position of the cephalic lateral crural margin relative to the caudal margin and advocates stabilization of inherent lateral crural instability prior to tip shaping techniques. If these issues are not addressed, tip–alar aesthetics may not be maintained long-term and postoperatively a shadow line that descends from the dorsal aesthetic lines and wraps around the paradomes, infratip and to the other side can ensue (an amorphous “sausage-like” appearance).

Alar flaring is frequent. Conservative alar base resections are often required due to nostril flaring, and should be performed at the end of the operation, after the columellar incision is closed. Excessive narrowing of the alar base should be avoided. Further resection can be performed during a simple office procedure.

Correction of alar–columellar disharmony30 is mandatory and often manifests as a “hanging columella” deformity. Alar retraction in primary rhinoplasty is rarely seen in the Middle Eastern population. Correction of excess columellar show may require medial crural septal sutures for proper tip rotation, but the nasolabial angle should not be overcorrected which will lead to racial incongruity. There may be a tendency to overcorrect due to the presence of severe caudal tip position. Over-rotation is a common indication for revision.

A nostril-to-tip ratio of approximately 60 : 40 should be present.31 After proper correction of tip rotation/projection, alar–columellar discrepancy, and alar base positioning, any residual nostril abnormalities will become apparent. This will often be due to flaring medial crural footplates, short nostril deformity31 (soft triangle excess), or enlarged nostril size. Footplate excision or suturing (mattress “cinching suture across columellar base) along with intercrural space soft tissue excision adds further refinement to the alar base–nostril relationship.14

Case 3

Middle Eastern

This 41-year-old female with Fitzpatrick type III skin who did not like her dorsal hump and unrefined tip, which appeared “flat” to her (Fig. 43.C3). She had a large dorsal hump, poorly shaped nasal tip that lacks projection, is plunging, as well as hyperdynamic. This patient demonstrates the classic Middle Eastern nasal morphology. She requested a more dramatic change in her tip and this required a secondary soft tissue debulking operation.

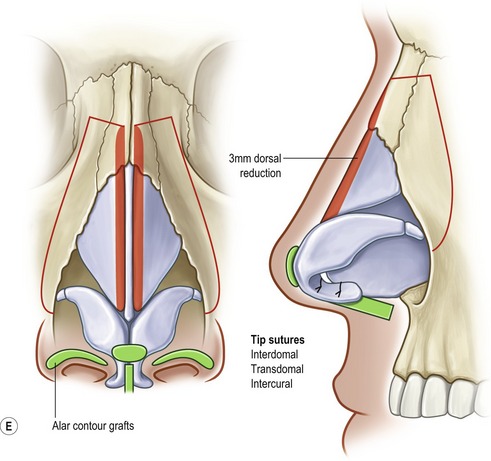

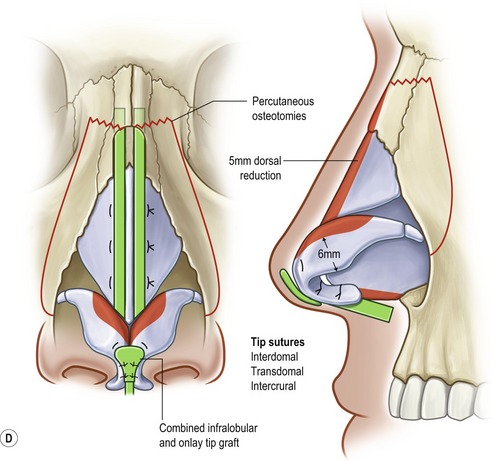

Fig. 43.C3 A, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. B, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. C, (i) Preoperative; (ii) postoperative. D, Intraoperative technique. E, Interaoperative technique. Rorich RJ, Ghavami A. Rhinoplasty for Middle Eastern Noses. Plast Reconst Surg. In press.

Operative steps

• Open rhinoplasty approach via a transcolumellar incision with bilateral infracartilaginous extensions and soft tissue debulking.

• 5 mm dorsal height reduction.

• Septoplasty with cartilage harvest, preserving 10 mm L-strut.

• Anterior septal angle reduction.

• Cephalic trim leaving intact 6 mm lateral crural strips.

• Floating columellar strut graft with medial crural septal sutures.

• Tip refinement with medial crural, transdomal, and interdomal sutures.

Asian

We will include only a short discussion of Asian noses as this topic is covered in the following chapter. Flowers10 elegantly lists the salient points. It should be stated that, unlike the ethnicities above, this ethnic group is harder to convince regarding the benefits of autogenous grafts. Most Asian patients know of someone who has had an Asian rhinoplasty quickly and effectively by way of a silicone implant. We find this ethnic group to most frequently desire and require significant dorsal augmentation (>4 mm). We advocate the following criteria for dorsal implant placement: (1) patient does not want rib graft under any circumstance; (2) has thick dorsal soft tissue; (3) dissection plane for implant placement is sub-periosteal; (4) implant is fixated with non-braided sutures superiorly and inferiorly; (5) L-shaped, combination dorsal-tip implant is not used due to high extrusion rate; and (6) a thorough discussion of the potential short and long-term complications are discussed preoperatively with discussion that future removal may require replacement with autogenous material.

Toriumi13 has had excellent results and a vast experience with autogenous rib which serve as both struts and nasal contouring grafts in both primary and secondary rhinoplasty. However, his patient population may be unique in that most present at consultation knowing that they will likely receive a rib graft.

Postoperative care

Prior to taping and splinting, its is helpful to irrigate the nasal cavity and nasopharynx with saline solution while using a “red-robin” catheter or nasogastric tube to prevent gastric filling with bloody liquid. Immediate care includes placement of internal Doyle splints, meticulous taping after cleaning with alcohol and then application of Mastisol. An Aquaplast or Denver type splint is placed next with care not to overly pinch and elevate the soft tissue underneath. Below are abbreviated guidelines for postoperative care that we provide our patients:

• Elevate head for 3–5 days. Swelling will peak in 48–72 hours.

• After your surgery start with a liquid diet and then progress to a soft diet. The next day you can begin a soft, regular diet but for 2 weeks avoid foods that require excess lip movement such as apples, corn on the cob, etc. You will probably have bloody nasal discharge for 3–4 days and may change the drip pad under your nose as often as needed. Do not rub or blot your nose, as this will tend to irritate it. You may discard the drip pad and remove the tape on your cheeks when the drainage has stopped. To prevent bleeding, do not sniff or blow your nose for the first 2 weeks after surgery. Try not to sneeze, but if you do, sneeze through your mouth.

• While the nasal splint is on, you may have your hair washed beauty salon fashion. Take care to prevent the nasal splint from getting wet. The nasal splint will be removed in 6–7 days after surgery. After the nasal splint is removed, the nose can be washed gently with a bland soap and make-up can be applied. Moisturizing creams can be used if the nose is dry.

• After the splint is removed, do not wear glasses or allow anything else to rest on your nose for 4 weeks. Glasses should be taped to the forehead. (We will show you how.) Contacts can be worn as soon as the swelling has decreased enough for them to be inserted.

• Keep the inside edges of your nostrils and any stitches clean by using a Q-Tip saturated with hydrogen peroxide followed by a thin coating of Polysporin or Bacitracin ointment. This will help prevent crust from forming. You may advance the Q-Tip into the nose as far as the cotton on the Q-Tip, but no further.

• Protect your nose from excessive sun exposure for 6 months. Wear wide brim med hats and/or a good sunscreen (SPF-30 or greater) with both UVA and UVB protection if you have to be in the sun for prolonged periods.

• Avoid strenuous activity (increasing your heart rate above 100 beats per minute) i.e., aerobics, heavy lifting, and bending over for the first 3 weeks after surgery. After 2 weeks you should slowly increase your activities so you will be back to normal by the end of the 3rd week. Avoid lifting anything heavier than 10 lb for 3 weeks following surgery.

• After your sutures are removed and the internal/external splints are removed it is recommended that you use a saline solution (salt water) (Ocean or Generic Saline Nasal Spray) to gently remove crusty formation from inside your nose especially if you had internal nasal surgery such as septal reconstruction or inferior turbinate resection.

• If you experience increased nasal bleeding with bright red blood (with a need to change nasal pad every 30–40 minutes) notify your doctor immediately. You should sit up and apply pressure to the end of your nose for 15 minutes and you can use Afrin spray to stop the oozing in the interim. Bleeding usually stops with these maneuvers.

Case 4

Operative steps

• Open transcolumellar approach

• Wide undermining with soft tissue debulking

• Component dorsum reduction (5 mm)

• Low to low percutaneous osteotomies

• Cephalic trim preserving 6 mm rim strips

• Depressor septi nasi muscle resection

• Intercrural, transdomal, and interdomal sutures

Complications

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Thorough discussion with patient with regard to aesthetic goals (magazine images, computer imaging, illustrations, etc).

• Must address soft tissue envelope by proper filling and support grafts.

• Preserve native cartilage as much as possible (i.e. LLC turnover and autospreader flaps).

• Liberal use of lateral crural struts, alar contour grafts, auto and standard spreader grafts, and infratip lobule onlay grafts.

• Soft tissue debulking when necessary (tip, supratip, and paradomal region).

Pitfalls

• Poor soft tissue envelope support with subsequent buckling, secondary tip amorphousness.

• Creating racial incongruity.

• Tip suturing and modification without use of support struts (anatomical and non-anatomical).

• Improper balance between tip–dorsal aesthetics.

• Over-correction of tip rotation, dorsal reduction, alar base narrowing, and/or tip shaping.

Summary of steps

1. A preoperative evaluation and treatment plan that recognizes and incorporates the ethnic naso-facial morphology is critical.

2. In general, African-American patients, like Asian patients, need augmentation in multiple dimensions.

3. Wide undermining is required for exposure, recruitment of nasal skin, and more even re-distribution of soft tissue healing forces (may aid in reduction of postop notching and buckling).

4. The undersurface of the nasal skin, particularly in the supratip, domal, and paradomal region should be trimmed to, but not past the level of the subdermal plexus.

5. Soft tissue debulking may improve the contractile ability of the skin to reveal the underlying framework established.

6. Taping and massage postoperatively plays an important role in limiting fibrous edema and thickened scarring between the skin and cartilage.

7. The gold standard in dorsal augmentation is rib cartilage.

8. The final assessment for dorsal augmentation should be made after osteotomies (when indicated) and tip enhancement.

9. The new cartilaginous frame/shape must be established through maneuvers that increase tip support along with refinement.

10. A combination of tip suturing techniques is usually needed.

11. Alar contour grafts are often needed to prevent notching at the soft triangle.

12. Skin redraping throughout the process of tip shaping helps determine the influence of each maneuver on the external surface, which is the ultimate aesthetic goal.

13. Lastly, enhancement of nostril shape and alar base reduction is usually needed.

1. Roe JO. The deformity of the pug nose and its correction by a simple operation. Med Rec. 1887;31:621.

2. Joseph J. Nasenplastick und sonstige Gesichtsplastik nebst einen Anhang ueber Mammaplastik. Leipzig: Verlag von Curt Kabitzsch; 1931.

3. Rohrich RJ, Muzaffar AR. Rhinoplasty in the African-American patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1322.

4. Ofodile FA, Bokhari F, Ellis C. The Black American nose. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;31:209.

5. Ofodile FA, Bokhari F. The African-American nose: Part II. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;34:123.

6. Rees TD. Nasal plastic surgery in the Negro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43:13.

7. Falces E, Wesser D, Gorney M. Cosmetic surgery of the noncaucasian nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;45:317.

8. Bizrah MB. Rhinoplasty for Middle Eastern patients. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2002;10:381.

9. Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A. Rhinoplasty for the Middle Eastern nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 123(4), 2009.

10. Flowers RS. The surgical correction of the non-Caucasian nose. Clin Plast Surg. 1977;4(1):69.

11. Ortiz-Monasterio F, Olmedo A. Rhinoplasty on the Mestizo nose. Clin Plast Surg. 1977;4:89.

12. Gonzalez-Ulloa M. The fat nose. Aesth Plast Surg. 1984;8:135.

13. DeRosa J, Toriumi DM, The Asian nose, 2nd edn. Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Adams WP, eds. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters, Quality Medical Publishing, St Louis, 2007;Vol. 2:1167.

14. Millard DR. Alar cinch in the flat, flaring nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;65:669.

15. Daniel RK. Hispanic rhinoplasty in the United States with emphasis on the Mexican American nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(1):244.

16. Matory WE, Falces E. Non-Caucasian rhinoplasty: a 16-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:239.

17. Erol OO. The Turkish delight: a pliable graft for rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2229.

18. Daniel RK, Calvert JW. Diced cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:2156.

19. Tebbetts JB. Shaping and positioning the nasal tip without structural disruption: a new, systematic approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:61.

20. Ghavami A, Janis JE, Acikel C, Rohrich RJ. Tip shaping in primary rhinoplasty: An algorithmic approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1229.

21. Guyuron B, Behmand RA. Nasal tip sutures. Part II: The interplays. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1130.

22. Behmand RA, Ghavami A, Guyuron B. Nasal tip sutures. Part I: The evolution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1125.

23. Sanchez AE. Rhinoplasty in the “chata” nose of the Caribbean. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1980;4:169.

24. Milgrim LM, Lawson W, Cohen AF. Anthropometric analysis of the female Latino nose. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1079.

25. Byrd HS, Salomon J, Flood J. Correction of the crooked nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2148.

26. Rohrich RJ, Muzaffar AR, Janis JE. Component dorsal hump reduction: The importance of maintaining dorsal aesthetic lines in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(5):1298.

27. Byrd HS, Meade RA, Gonyon DL, Jr. Use of the autospreader flap in primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1897.

28. Gunter J.P, Friedman RM. Lateral crural strut graft: technique and clinical applications in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:943.

29. Toriumi DM. New concepts in nasal tip contouring. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8:156.

30. Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Friedman RM. Classification and correction of alar-columellar discrepancies in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:643.

31. Guyruron B, Ghavami A, Wishnek SM. Components of the short nostril. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1517.