Chapter 105 The Epidemiology of Adolescent Health Problems

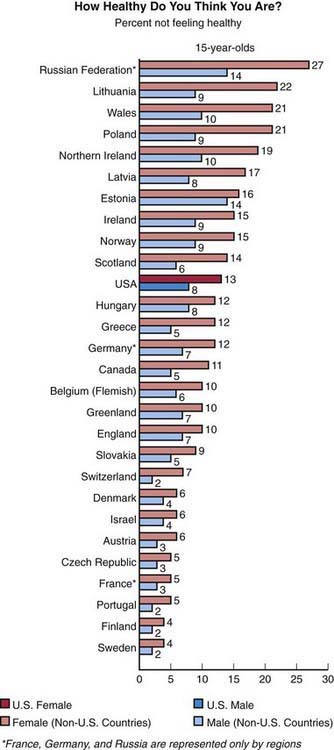

Health outcomes also vary. About 16 million women aged 15-19 yr old give birth annually, accounting for 10% of births worldwide. The average adolescent birthrate in low-income countries is 5-fold that of high-income countries. Complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death among adolescents in developing countries; death as an outcome of pregnancy is rare in developed countries. Perceptions of feeling healthy also vary greatly by country as shown in Figure 105-1; those who do not feel healthy increases proportionately with age.

Figure 105-1 Proportion of 15 yr old youth from 28 nations who report not feeling healthy.

(From Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau: U.S. teens in our world. Understanding the health of U.S. youth in comparison to youth in other countries (website). www.mchb.hrsa.gov/mchirc/_pubs/us_teens/main_pages/ch_1.htm. Accessed April 16, 2010.)

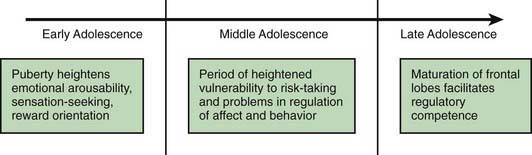

Despite these variations by geographic region and level of economic development, there are many similarities in adolescent health issues. In all nations, adolescence is a time of immense biologic, psychologic, and social change (Chapter 104). Many of the psychologic changes have a biologic substrate in the development and eventual maturation of the central nervous system, particularly the frontal lobe areas responsible for executive functioning (Fig. 105-2). In addition to cognitive development, there are both risk and protective factors for adverse adolescent health behaviors that are dependent on the social environment as well as the mental health of an adolescent (Table 105-1).

Table 105-1 IDENTIFIED RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR ADOLESCENT HEALTH BEHAVIORS

| BEHAVIOR | RISK FACTORS | PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Depression and other mental health problems, alcohol use, disconnectedness from school or family, difficulty talking with parents, minority ethnicity, low school achievement, peer smoking | Family connectedness, perceived healthiness, higher parental expectations, low prevalence of smoking in school |

| Alcohol and drug misuse | Depression and other mental health problems, low self-esteem, easy family access to alcohol, working outside school, difficulty talking with parents, risk factors for transition from occasional to regular substance misuse (smoking, availability of substances, peer use, other risk behaviors) | Connectedness with school and family, religious affiliation |

| Teenage pregnancy | Deprivation, city residence, low educational expectations, lack of access to sexual health services, drug and alcohol use | Connectedness with school and family, religious affiliation |

| Sexually transmitted infections | Mental health problems, substance misuse | Connectedness with school and family, religious affiliation |

Adapted from Mclntosh N, Helms P, Smyth R, editors: Forfar and Arneil’s textbook of paediatrics, ed 6, Edinburgh, 2003, Churchill Livingstone, pp 1757–1768; and Viner R, Macfarlane A: Health promotion, Br Med J 330:527–529, 2005.

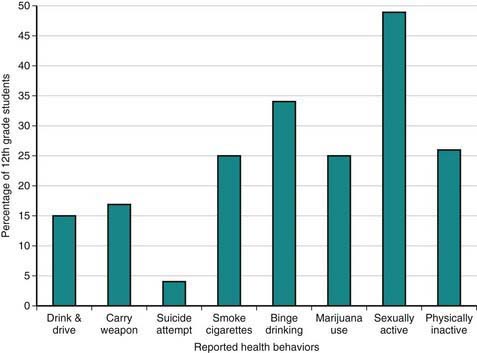

Geographic similarities are reflected in many adolescent health outcomes. Suicide is the 3rd leading cause of death among adolescents worldwide. In the USA, an estimated 13.8% of high school students seriously considered attempting suicide, and 6.3% had actually attempted suicide in the previous 12 mo. Experimentation with new behaviors leads to an increase in risky behaviors among adolescents in the USA (Fig. 105-3) and globally. The Global Youth Tobacco Survey, initiated by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1999, reveals that tobacco use is a major problem among adolescents ages 13-15 yr in all 6 regions of the globe (Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, Southeast Asia, and Western Pacific), averaging 17% globally, with a low of 11% in the Western Pacific region and a high of 22% in the Americas. Alcohol and illicit drugs are a major cause of concern in high-income countries and have also been estimated by the WHO to contribute 4% of the disease burden in adolescents and young adults in low- and middle-income countries. Adolescents and young adults worldwide have high rates of most common sexually transmitted infections in their countries. Persons in this age group in the USA have been estimated to account for nearly half of all incidents of sexually transmitted infections, although they represent only 25% of the sexually active population. A study of 9 developed countries revealed a similar pattern in many of the nations: >50% of cases of syphilis occurred among youth 15-24 yr in Romania and the Russian Federation; >50% of cases of gonorrhea occurred in this age group in Romania, the Russian Federation, the Slovak Republic, Canada, England and Wales, and the USA; and in 6 countries, youth this age were responsible for >50% of annually reported chlamydia cases.

Figure 105-3 Selected health risk behaviors among 12th grade high school students.

(Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2009 youth risk surveillance system (website). www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm. Accessed February 20, 2011.)

In the USA, injuries cause more than twice as many deaths among adolescents as do natural causes; motor vehicle traffic–related injuries and firearm-related injuries are the 2 leading causes of injury death among adolescents 10-19 yr of age (Chapter 5). Although infectious diseases remain important causes of death for adolescents in some low-income countries, adolescents worldwide are increasingly exposed to risk-taking behavior including violence. Worldwide, motor vehicle accidents are the greatest cause of death and disability among men ages 15-19 yr. For all causes of mortality resulting from unintentional injury there is an inverse relationship between mortality rates and per capita income except for motor vehicle traffic among adolescents and young adults; for this category, mortality is higher in high-income countries compared to low-income countries. Though mortality due to motor vehicle injury is decreasing among adolescents in higher income countries, it is increasing in low-income countries.

Access to Health Care

Access to health care may be limited for adolescents regardless of the country of residence. Adolescents in low-income countries experience reduced access to health care compared to their counterparts in wealthier nations for a range of reasons, including lack of facilities, long distances to facilities, inadequate transportation, and insufficient time to travel to facilities. There are also cultural prohibitions, such as gender, poor education, and inadequate financing. Within countries, access is generally inversely related to socioeconomic status (Chapter 1).

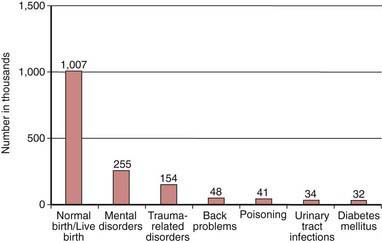

Adolescents are among the least likely of all age groups to be hospitalized. In 2004, childbirth was the leading cause of inpatient hospitalizations for adolescents and young adults ages 12-24 yr, followed by mental health disorders and trauma-related disorders, such as open wounds and fractures (Fig. 105-4).

Figure 105-4 Number of hospital inpatient stays by condition, ages 12-24 yr, 2004.

(Adapted from National Adolescent Health Information Center: 2008 fact sheet on health care access & utilization: adolescents & young adults, San Francisco, 2008, University of California, San Francisco. Source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Household Component Summary Tables, 2007.)

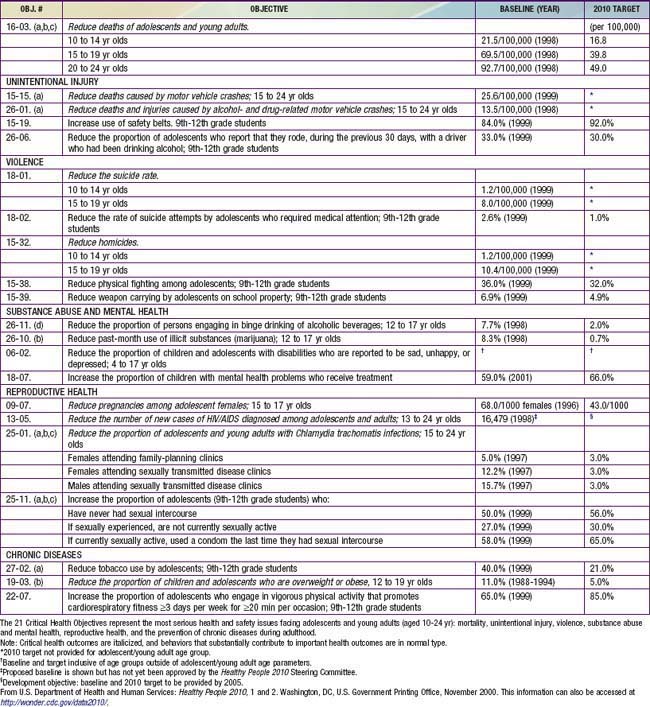

The National Initiative to Improve Adolescent Health by the Year 2010 has identified 21 critical health objectives for adolescents and young adults as a strategy to focus state and community resources and health professionals on improving the health status of U.S. youths (Table 105-2). Progress to date includes significant improvement in incidence of teen pregnancy and tobacco use, small increments of improvement in some areas (i.e., physical fighting, weapon carrying, safety belt use), and worsening trends for others such as motor vehicle crashes, chlamydial infections, and obesity. These health objectives are applicable to adolescents throughout the world.

Burstein GR, Lowry R, Klein JD, et al. Missed opportunities for sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus, and pregnancy prevention services during adolescent health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2003;111:996-1001.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Percentage of deaths from leading causes among teens aged 15–19 years. National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1234. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5745a7.htm. Accessed April 30, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual and reproductive health of persons aged 10–24 years, United States, 2002–2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(6):1-58.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59(SS-5):1-42.

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children and adolescents, ed 3, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

Irwin CEJr, Adams SH, Park MJ, et al. Preventive care for adolescents: few get visits and fewer get services. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e565-e572.

MacKay AP, Duran C. Adolescent health in the United States, 2007. National Center for Health Statistics; 2007.

National Adolescent Health Information Center. 2008 fact sheet on health care access and utilization: adolescents and young adults. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco; 2008.

Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:69-74.

Viner R, Booy R. Epidemiology of health and illness. Br Med J. 2005;330:411-414.

Viner R, Macfarlane A. Health promotion. Br Med J. 2005;330:527-529.

Waldvogel JL, Rueter M, Oberg CN. Adolescent suicide: risk factors and prevention strategies. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2008;38:105-132.

World Health Organization. Revised global burden of disease (GBD) 2002 estimates. Geneva: WHO; 2002. (website) www.who.int/healthinfo/bodgbd2002revised/en/index.html