Chapter 19 The endocrine system

Hypoglycaemic and antidiabetic herbs

Guar gum, Cyamopsis tetragonolobus (L.) Taubert (Cyamopsidis semen)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

The flour reduces pre- and postprandial glucose levels and is usually given with meals, and may also be of use in lowering blood lipid levels (Butt et al 2007). Like other bulk fibre preparations, it has other clinical effects such as the alleviation of diarrhoea, and it has been advocated as a slimming aid, and this does seem to be justified. It is also used as a thickening and suspending agent in foods, and as a tablet binder. The usual dose of the powdered gum is 5 g given with each meal. Few side effects have been noted, but patients treated with guar sometimes consider it to be rather unpalatable when made into foods.

Gymnema, Gymnema sylvestre R.Br.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

The herb is a traditional treatment for diabetes in India but, although widely used, there is insufficient clinical evidence available to recommend this herb as yet. The antihyperglycaemic properties are due to the gymnemic acids and other saponins. Oral administration of a specific standardized extract OSA(R) (1 g/day, 60 days) induced significant increases in circulating insulin and C-peptide, which were associated with a reduction in fasting and post-prandial blood glucose. In vitro measurements using isolated human islets of Langerhans demonstrated direct stimulatory effects of OSA(R) on insulin secretion from human β-cells, consistent with an in vivo mode of action through enhancing insulin secretion (Al-Romaiyan et al 2010). The leaf extract also has hypolipidaemic activity in human patients and animals fed a high-fat diet (Kanetka et al 2007). The usual dose is up to 4 g of leaf daily. Gymnemic acids are well tolerated, but care should be taken when used in conjunction with other antidiabetic agents.

Karela, Momordica charantia L.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Both the fruit and the leaf have hypoglycaemic effects. The extract causes hypoglycaemia in animals and human diabetic patients, and several clinical studies have confirmed benefits (see review by Grover and Yadav 2004), but a recent Cochrane review (Ooi et al 2010) states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend it for type 2 diabetes mellitus, and that further studies are required to address issues of standardization and the quality control of preparations. It has also been used to treat asthma, skin infections and hypertension (Grover and Yadav 2004). Contraceptive and teratogenic effects have been described in animals, so care should be taken in pregnant women, although cooking the vegetable may well destroy many of the toxins.

Phytoestrogens

There are many plants that contain oestrogenic substances (phytoestrogens), and pharmacological and epidemiological evidence suggests that they act as mild oestrogens or, in certain circumstances, as anti-oestrogens (by binding to oestrogen receptors and preventing occupation by natural oestrogens). They generally have beneficial effects, including chemopreventive activity. As well as the herbs mentioned below, many pulses (which are legumes) contain phytoestrogens, as do linseed and hops. The main chemical types of phytoestrogen are the isoflavones, coumestans and lignans, and some species of palm even contain similar hormones (e.g. estriol) to those found in the human body. The common occurrence of these substances has implications for men as well as for women, in that the incidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia is lower in men, and menopausal symptoms in women, in societies consuming significant amounts of foods containing these substances in their normal diet. However, a recent case-control study in the UK found no significant associations between phytoestrogen intake and breast cancer risk, although colorectal cancer risk was inversely associated with enterolignan intake in women but not in men (Ward and Kuhnle 2010). Soya phytoestrogen intake may even have a beneficial effect on tumour recurrence (Roberts 2010). As the majority of studies have not involved women with breast cancer and are of short duration, it would be wise for patients with hormone-dependent cancers to avoid taking phytomedicines known to affect hormone levels.

Red clover, Trifolium pratense L.

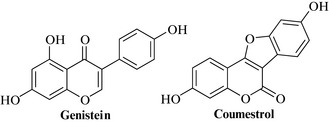

Constituents

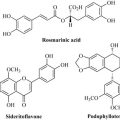

The major actives are phytoestrogens of two types: the isoflavones genistein (Fig. 19.1), afrormosin, biochanin A, daidzein, formononetin, pratensein, calyconin, pseudobaptigenin, orobol, irilone and trifoside, and their glycoside conjugates; and the coumestans coumestrol (Fig. 19.1) and medicagol.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Red clover was traditionally used for skin complaints such as psoriasis and eczema, and as an expectorant in coughs and bronchial conditions. However, it has recently been used more as a source of the isoflavones, for a natural method of hormone replacement therapy (for review, see Sabudak and Guler 2009). The isoflavones are oestrogenic in animals but the clinical use for menopausal women has not yet been well supported by clinical studies, except for a marginally significant effect for treating hot flushes in menopausal women (Coon et al 2007). Biochanin A inhibits metabolic activation of the carcinogen benzo(a)pyrene in a mammalian cell culture, suggesting chemopreventive properties. Red clover extracts also inhibit cytochrome P450 3A4 in vitro, which supports such a use. Red clover is considered safe.

Soya, Glycine max (L.) Merr.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

The isoflavones and coumestans are oestrogenic, and are now being used as a natural form of hormone replacement therapy, although the evidence for this is not conclusive. Dietary inclusion of whole soya foods appears to produce a reduction in some clinical risk factors for osteoporosis, and soy isoflavone supplements moderately decreased the bone resorption marker deoxypyridinoline but did not affect the bone formation markers alkaline phosphatase and serum osteocalcin in menopausal women, although the effects varied between studies (Taku et al 2010).

Cardiovascular disease and lipid profiles in menopausal women have been reported to be improved by consumption of whole soya foods, although results have been conflicting. In an open study of 190 healthy postmenopausal women given 35 mg of soy isoflavones, a reduction in the number of hot flushes was found (Albert et al 2002), but no improvement was seen in women with breast cancer given a beverage containing 90 mg of soy isoflavones. There is still much work to be done on the clinical effects of the isoflavones in soya, but at present it appears that they are beneficial with few adverse effects (for review, see Messina 2010). Opposing advice has been given regarding the safety of dietary phytoestrogen use for women with previous breast cancer. However, as mentioned above, the majority of studies have not been conducted in women with breast cancer and many are of short duration. Soya is considered to be non-toxic.

Hormonal imbalance in women

Black cohosh, Cimicifuga racemosa Nutt. (Cimicifugae racemosae rhizome)

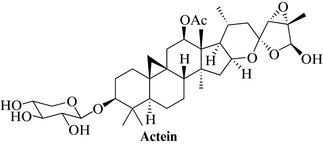

Constituents

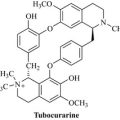

The active components of black cohosh are considered to be the triterpene glycosides, such as actein (Fig. 19.2), 27-deoxyactein and several cimicifugosides; the flavonoids may contribute to the activity.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Hormonal and antiinflammatory effects have been described for black cohosh and reductions in serum luteinizing hormone concentrations have been documented for methanolic and lipophilic extracts, but there are conflicting data on the oestrogenic activity of the herb. Although there is some evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials, it does not consistently demonstrate an effect of black cohosh on menopausal symptoms, including flushes, and further rigorous trials seem warranted (Borrelli and Ernst 2008). Black cohosh use appears safe in women with previous breast cancer (Roberts 2010), but the majority of studies regarding the efficacy of such herbal treatments have not been conducted in women with breast cancer and many are of short duration. Adverse effects are rare, but may include gastrointestinal disturbance and lowering of blood pressure with high doses. It should be avoided in pregnancy and lactation because of insufficient data.

Chasteberry, Vitex agnus-castus L. (Agni casti fructus)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Extracts of agnus castus and isolated diterpene constituents display dopamine receptor binding activity in vitro. For example, dopaminergic activity and inhibition of prolactin secretion has been demonstrated in vitro for rotundifuran. Dopaminergic activity is associated with inhibition of prolactin synthesis and release. Modern pharmaceutical uses of agnus castus include menstrual cycle disorders, premenstrual syndrome and mastalgia (cyclical breast pain). There is some evidence from randomized controlled trials to support the effects of proprietary preparations of agnus castus in relieving breast pain in women with mastalgia. Alleviation of symptoms of premenstrual syndrome is also supported by results of randomized controlled trials (for example, Ma et al 2010). In addition, clinical studies provide some evidence to support the effects of agnus castus on lowering prolactin concentrations in hyperprolactinaemia. Other studies have reported that agnus castus does not markedly affect prolactin concentrations in women with normal basal prolactin levels. Although evidence from rigorous randomized controlled trials is lacking for agnus castus in the alleviation of menopausal symptoms, emerging pharmacological evidence supports a role in this context (for review, see Van Die et al 2009).

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Nettle, Urtica dioica L. (Urticae herba, radix)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Modern uses of nettle extracts are focused mainly on symptom relief in BPH and adjuvant treatment (i.e. in addition to non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs) in arthritis and rheumatism. Evidence from in vitro and in vivo (mice) studies measuring sex hormone-binding globulin to human prostate membranes, and by inhibition of proliferation of human prostatic epithelial and stromal cells, suggests that nettle root extracts have beneficial effects on BPH tissue. Several compounds from the roots are also known to be aromatase inhibitors, and there is evidence from some clinical trials to support the use of nettle root extracts for relief of symptoms associated with BPH (for review, see Chrubasik et al 2007). Nettle leaf extracts inhibit the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB, partially inhibit cyclo-oxygenase and lipoxygenase, and inhibit tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-1β secretion stimulated by lipopolysaccharide. Nettle preparations are generally thought of as safe, with few (if any) adverse events being reported.

Pygeum bark, Prunus africana (Hook. f.) Kalkm. (Pruni africani cortex)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Traditionally used for micturition problems and now for BPH, pygeum extract has antiproliferative and apoptotic effects on proliferative prostate fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, but not on smooth muscle cells (Quiles et al 2010). The compound N-butylbenzene-sulfonamide, isolated from P. africanum, is a specific androgen receptor antagonist which inhibits both endogenous prostate serum antigen expression and growth of human prostate cancer cells, but does not interact with oestrogen receptors (Papaioannou et al 2010). Clinical studies have shown the extract to be moderately effective, and it may be a useful treatment option for men with lower urinary symptoms consistent with BPH. However, the studies are small, of short duration, use varied doses and preparations, and rarely report outcomes using standardized validated measures of efficacy, so further work is needed (Wilt et al 2002). Acute and chronic toxicity and mutagenicity tests have shown no adverse effects, and the extract appears to be well-tolerated in men when administered over long periods. It is often used in combination with nettle.

Saw palmetto, Serenoa serrulata Hook. f. (Sabalis serrulatae fructus)

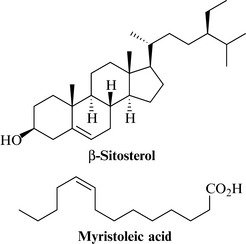

Constituents

The phytochemistry of saw palmetto is fairly well known, although precisely which components are responsible for the pharmacological effects have yet to be established. Constituents likely to be important include: the fatty acids capric, caprylic, lauric, oleic, myristoleic, palmitic, linoleic and linolenic acids; the monoacyl glycerides 1-monolaurin and 1-monomyristicin; phytosterols such as β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol, lupeol and cycloartenol (Fig. 19.3). Long-chain alcohols (farnesol, phytol and polyprenolic alcohols) and flavonoids are present, as well as immunostimulant, high-molecular-weight polysaccharides containing galactose, arabinose, mannose, rhamnose and glucuronic acid.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Saw palmetto is now mainly used to treat BPH. This is supported by evidence from several randomized controlled trials, which also provided preliminary evidence that extracts (usually liposterolic) achieve improvements similar to those seen with the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride (Mantovani et al 2010). However, other studies show no effect and the efficacy is disputed (Barnes 2009; Tacklind et al 2009, Mantovani 2010). Post-marketing surveillance studies suggest that saw palmetto extracts are well tolerated, and comparative clinical studies indicate that they have a more favourable safety profile than finasteride, at least in the short term. Liposterolic and ethanolic extracts of saw palmetto inhibit 5α-reductase (the enzyme which catalyses the conversion of testosterone to 5α-dihydrotestosterone in the prostate) in vitro; other studies have described beneficial effects in animal models of BPH. Spasmolytic activity, which may also contribute to improvements in BPH, has also been documented in vivo (rats) for an ethanolic extract of saw palmetto. In vitro growth arrest of prostate cancer LNCaP, DU145, and PC3 cells (Yang 2007) and in vivo oestrogenic and antiinflammatory activities have been reported for extracts of saw palmetto, and may be due to the high content of β-sitosterol. The antiinflammatory effects may also be due to the presence of the polysaccharides.

Al-Romaiyan A., Liu B., Asare-Anane H., et al. A novel Gymnema sylvestre extract stimulates insulin secretion from human islets in vivo and in vitro. Phytother. Res.. 2010;24:1370-1376.

Albert A., Altabre C., Baró F., et al. Efficacy and safety of a phytoestrogen preparation derived from Glycine max (L.) Merr in climacteric symptomatology: a multicentric, open, prospective and non-randomized trial. Phytomedicine. 2002;9(2):85-92.

Barnes J. Saw palmetto. Serenoa repens. Also known as Serenoa serrulata, Sabal serrulata and the dwarf palm. J. Prim. Health Care. 2009;1:323.

Borrelli F., Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review of its efficacy. Pharmacol. Res.. 2008;58:8-14.

Butt M.S., Shahzadi N., Sharif M.K., Nasir M. Guar gum: a miracle therapy for hypercholesterolemia, hyperglycemia and obesity. CRC Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr.. 2007;47:389-396.

Coon J.T., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Trifolium pratense isoflavones in the treatment of menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:153-159.

Chrubasik J.E., Roufogalis B.D., Wagner H., Chrubasik S. A comprehensive review on the stinging nettle effect and efficacy profiles. Part II: urticae radix. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:568-579.

Grover J.K., Yadav S.P. Pharmacological actions and potential uses of Momordica charantia: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2004;93:123-132.

Kanetka P., Singhal R., Kamat M. Gymnema sylvestre: a memoir. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr.. 2007;41:77-81.

Ma L., Lin S., Chen R., Wang X. Treatment of moderate to severe premenstrual syndrome with Vitex agnus castus (BNO 1095) in Chinese women. Gynecol. Endocrinol.. 2010;26:612-616.

Mantovani F. Serenoa repens in benign prostatic hypertrophy: analysis of 2 Italian studies. Minerva Urol. Nefrol.. 2010;62:335-340.

Messina M. A brief historical overview of the past two decades of soy and isoflavone research. J. Nutr.. 2010;140:1350S-1354S.

Ooi C.P., Yassin Z., Hamid T.A. Momordica charantia for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Feb 17. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2010;2. CD007845

Papaioannou M., Schleich S., Roell D., et al. NBBS isolated from Pygeum africanum bark exhibits androgen antagonistic activity, inhibits AR nuclear translocation and prostate cancer cell growth. Invest. New Drugs. 2010;28:729-743.

Quiles M.T., Arbós M.A., Fraga A., de Torres I.M., Reventós J., Morote J. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of the herbal agent Pygeum africanum on cultured prostate stromal cells from patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Prostate. 2010;70:1044-1053.

Roberts H. Safety of herbal medicinal products in women with breast cancer. Maturitas. 2010;66:363-369.

Sabudak T., Guler N. Trifolium L. – a review on its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Phytother. Res.. 2009;23:439-446.

Tacklind J., Donald R., Rutks I., Wilt T.J. Serenoa repens for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Apr 15. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2009;2. CD001423

Taku K., Melby M.K., Kurzer M.S., Mizuno S., Watanabe S., Ishimi Y. Effects of soy isoflavone supplements on bone turnover markers in menopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Bone. 2010;47:413-423.

Van Die M.D., Burger H.G., Teede H.J., Bone K.M. Vitex agnus-castus (Chaste-Tree/Berry) in the treatment of menopause-related complaints. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2009;15:853-862.

Ward H.A., Kuhnle G.G.C. Phytoestrogen consumption and association with breast, prostate and colorectal cancer in EPIC Norfolk. Arch. Biochem. Biophys.. 2010;501:170-175.

Wilt T., Ishani A., Mac Donald R., Rutks I., Stark G. Pygeum africanum for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2002. CD001044

Yang Y., Ikezoe T., Zheng Z., Taguchi H., Koeffler H.P., Zhu W.G. Saw Palmetto induces growth arrest and apoptosis of androgen-dependent prostate cancer LNCaP cells via inactivation of STAT 3 and androgen receptor signaling. Int. J. Oncol.. 2007;31:593-600.