CHAPTER 41 The Dorsal Ligaments of the Wrist

Relatively little attention or significance had been given to the dorsal ligaments of the wrist until more recent studies described the anatomical and mechanical properties of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament and the dorsal intercarpal ligament of the wrist1 and subregions of the scapholunate2–4 and lunotriquetral5 interosseous ligaments. An explanation of the functional design of the dorsal wrist ligament configuration was also offered recently.6 Dorsal approaches to the wrist have also generally ignored the ligament anatomy. Even commonly referenced and used illustrations and diagrams of the dorsal ligaments of the wrist are anatomically inaccurate.7,8

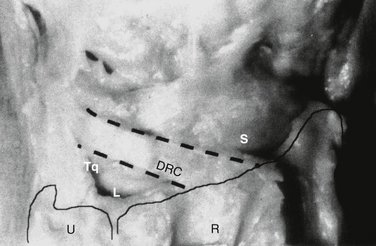

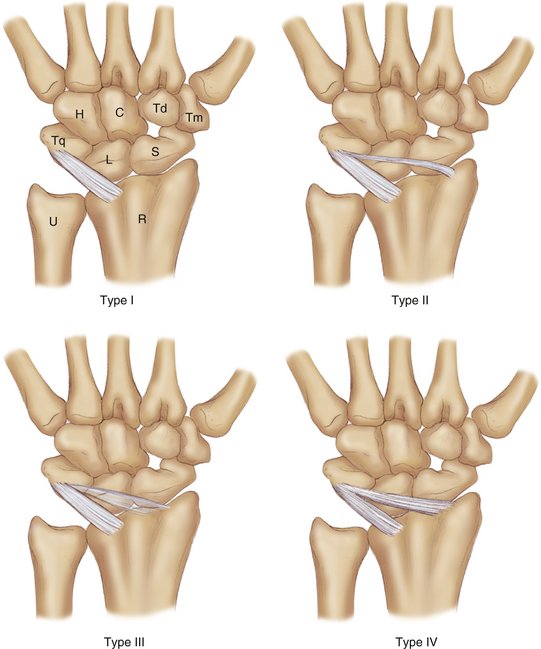

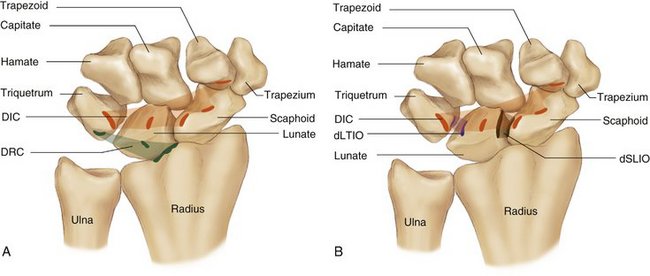

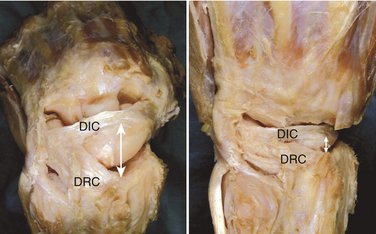

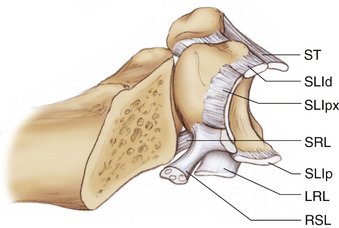

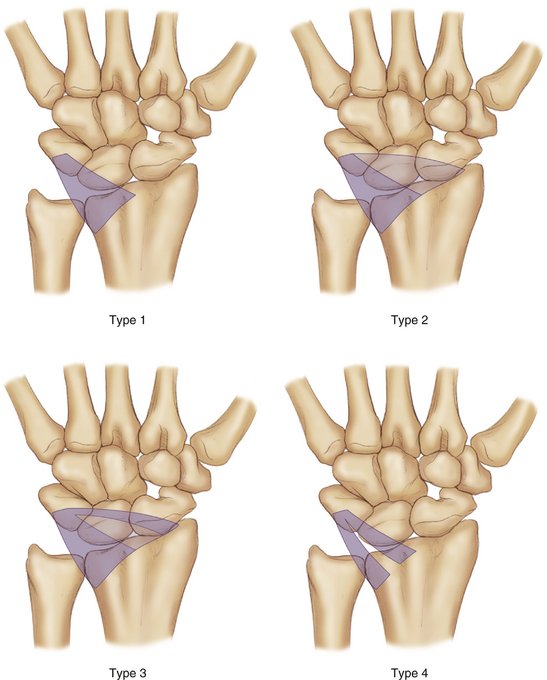

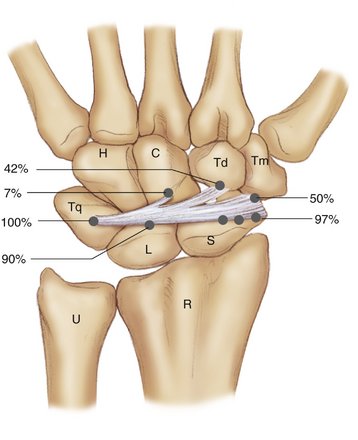

The specific anatomy of the dorsal radiocarpal (DRC) and dorsal intercarpal (DIC) ligaments of the wrist has been reported, but relatively little attention or importance has been ascribed to these ligaments in the past. The DRC has also been referred to in the literature as the dorsal radiotriquetral and the dorsal radiolunotriquetral ligament9–11 (Fig. 41-1). The distal attachments of the DRC ligament have been described by a number of authors.9–14 Some describe the ligament attaching onto the lunate,9,11,12,14 others describe it attaching onto the lunate and the scaphoid,10 whereas others report it attaching onto the lunate and capitate.13 Berger and Garcia-Elias9 described the DRC ligament attaching to the lunate and intermingling with fibers of the lunotriquetral ligament. The attachment of the DRC ligament proximally was described by all of those authors as being proximally at the dorsal aspect of the radius and its distal attachment, at least in part, including the dorsal tubercle of the triquetrum.9–14 A number of authors9–14 have reported that the DRC ligament was found to consistently have an osseous attachment proximally, at the dorsal aspect of the radius, and, distally, at the dorsal tubercle of the triquetrum. It was also found to consistently have an osseous attachment onto the distal ulnar aspect of the dorsal lunate and dorsal portion of the lunotriquetral interosseous ligament, as described by Berger and Garcia-Elias9 and Viegas and colleagues (Fig. 41-2). There were no attachments onto the scaphoid for the DRC ligament, but there was a dorsal branch or branches of the DRC ligament from the radius to the triquetrum that passed over, but did not attach to, the dorsal aspect of the proximal scaphoid, which may offer some dorsal support to the scaphoid in type II and III DRC ligaments as classified by Viegas and colleagues.6 This anatomical classification system (Fig. 41-3) was a modification of Mizuseki’s classification10 (Fig. 41-4) of the DRC ligament. Types I and IV are classified the same as his classification types 1 and 4. Mizuseki10 described that type 2, in addition to type 1, fibers have thin deltoid fibers covering the scaphoid, converging onto the triquetrum. Viegas and colleagues1 stated that these thin deltoid fibers were not detected in the dorsal structures.

FIGURE 41-2 Anatomy and the osseous/ligamentous attachments of the DRC.

(From Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM: The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: anatomy, mechanical properties and function. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999; 24: 456-468, with permission.)

FIGURE 41-4 Mizuseki’s classification of the dorsal radiocarpal ligament.

(From Mizuseki T, Ikuta Y: The dorsal carpal ligament: their anatomy and function. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1989; 14:91-98, with permission.)

Function of the DRC ligament has been proposed by a number of authors.10,12,13,15 The DRC ligament has been attributed to maintaining the lunate in apposition to the distal radius.16 The direction of the fibers of the DRC ligament implies that the triquetrum is prevented from ulnar translation by the DRC ligament and the volar radiolunotriquetral ligament.10 The DRC ligament also functions as a stabilizer and pronator of the wrist. When the forearm pronates, the DRC ligament draws the attached carpus and hand passively into pronation.12,13 Some biomechanic and kinematic studies have been performed on the DRC ligament. In a 1990 anatomical and biomechanical study by Viegas and colleagues17 that was designed to better understand the pathoanatomy and pathomechanics involved in volar intercalated segment instability (VISI) deformity of the wrist, it was found that the DRC must be attenuated or disrupted for a static VISI to develop. In fact, that study demonstrated that disruption of the DRC alone would result in a nondissociative static VISI deformity. Horii and associates,18 in 1991, also confirmed the importance of the DRC in stabilizing the carpus and preventing a static VISI deformity.

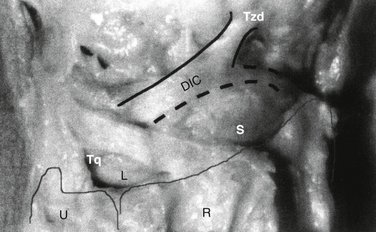

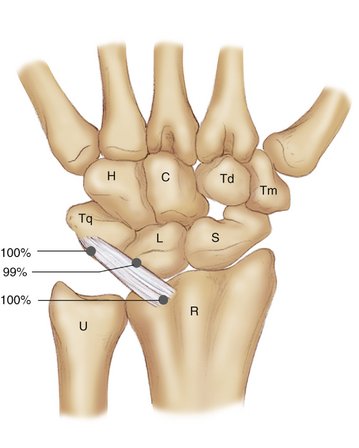

A limited number of anatomical and biomechanical papers on the dorsal intercarpal ligament (Fig. 41-5) have been published. The osseous attachments of the DIC ligament have been described by a number of authors.9,10,13,19,20 Mizuseki and Ikuta described the DIC as having attachments on the dorsal tubercle of the triquetrum and trapezoid, on the capitate, and at the dorsal rough groove of the scaphoid.10 Berger and Garcia-Elias9 reported that the DIC attached to the triquetrum and the scaphoid and, to a lesser degree, on the dorsal surface of the trapezoid. Savelberg and coworkers19 found that the DIC attached to the triquetrum, the scaphoid, and the trapezium. Viegas and colleagues6 also classified the various anatomical types of DIC ligaments and found that the DIC ligament was composed of two sections. One section consisted of a more distal section of generally thinner fibers extending from the dorsal tubercle of the triquetrum to the dorsal aspect of the trapezoid or capitate. Another, more proximal thicker section extended from the dorsal tubercle of the triquetrum to the dorsal distal aspect of the lunate to the dorsal groove of the scaphoid and then to the proximal rim of the trapezium. They found that the attachment to the lunate of the DIC ligament was a consistent finding (Fig. 41-6). In 1997, Berger and Bishop described a surgical approach to the dorsal aspect of the wrist that they called a fiber-splitting or ligament-sparing approach.21 The dorsal arm of this approach follows what Berger previously described as the dorsal scaphotriquetral ligament.3 However, this would not spare the attachments of the DIC ligament, which Viegas and coworkers6 have demonstrated attach to the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum.

FIGURE 41-6 Anatomy and the osseous/ligamentous attachments of the DIC.

(From Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM: The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: anatomy, mechanical properties and function. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999; 24: 456-468, with permission.)

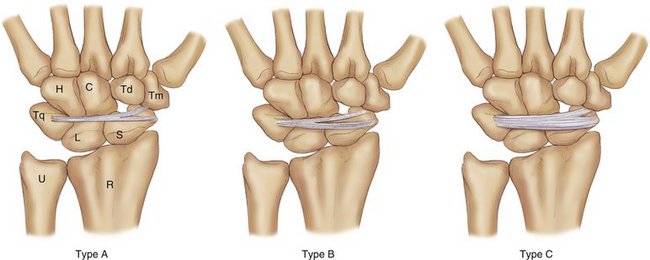

Smith20 classified the DIC ligament using three-dimensional Fourier transform magnetic resonance imaging techniques. His classification is similar to that of Viegas and colleagues6 (Fig. 41-7), but the reported incidence of each type was different. Smith20 reported the incidence of three types of DIC ligaments—type 1, 14%; type 2, 44%; and type 3, 38%—which is comparable to Viegas and colleagues’1 type C, 25.6%; type A, 30.0%; and type B, 44.4%, respectively. Smith20 believed that the main portion of the DIC ligament consisted of deep fibers, whereas the superficial fibers were very thin and were not considered to be an important stabilizer of the carpus. Mizuseki and Ikuta10 believed that the DIC ligament was always thin and seemed to be of little anatomical importance. Fahrer13 believed the DIC ligament was much less developed than the palmar structures. Berger and Garcia-Elias9 stated that the scaphotriquetral ligament (proximal DIC fibers) did have an important role in the transverse stabilization of the proximal carpal row.

It can be difficult to accurately delineate the anatomy and measure the dimensions of the ligaments of the wrist. Viegas and colleagues6 used a combination of meticulous dissections of both fresh and embalmed specimens to complete the task of detailing the ligament anatomy. That, in combination with observations from previous anatomical and biomechanical studies, has afforded the opportunity to gain some insight into the anatomy and function of the ligaments of the wrist. Despite this, the task of accurately detailing where one structure ends and another begins, particularly in the presence of the normal variability of human anatomy, remains challenging and may offer a reason for some of the variability in the literature.

Recently, Nagao and associates22 quantified and visually depicted the three-dimensional attachment sites of the carpal ligaments using a combination of detailed dissection, computed tomographic (CT) imaging, and a three-dimensional digitization technique. They visually demonstrated that the DIC ligament attaches to the dorsal aspect of scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum and how the DIC ligament partially overlaps with portions of the dorsal scapholunate interosseous (SLIO) and lunotriquetral interosseous (LTIO) ligaments (Fig. 41-8).

The mechanical properties of the dorsal ligaments of the wrist have been reported.16,19 The strongest ligaments are the palmar radiotriquetral ligament (210 N) and the DRC ligament (240 N).16 Only the DRC ligament and palmar radiocapitate ligament appear to have a relatively high Young’s modulus, about 93 megapascal (Mpa) and 83 Mpa, respectively.19 The DIC ligament, on average, has a Young’s modulus of 47.5 Mpa.19 Viegas and colleagues6 suggest that the DRC and DIC ligaments collectively deliver indirect dorsal radioscaphoid stability. They also explain that the combined mechanical properties of the DIC and the dorsal SLIO ligaments have mechanical strength (162.4 ± 64.7 N) comparable with the DRC (143.3 ± 41.5 N).

Dorsal ligamentous structures are important in maintaining carpal stability and alignment and in affording normal carpal kinematics, in addition to playing an important role in preventing the loss of integrity of the dorsal complex and the development of VISI deformities and in dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI), according to some reports.1,6

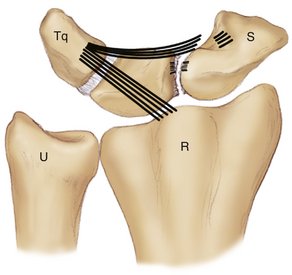

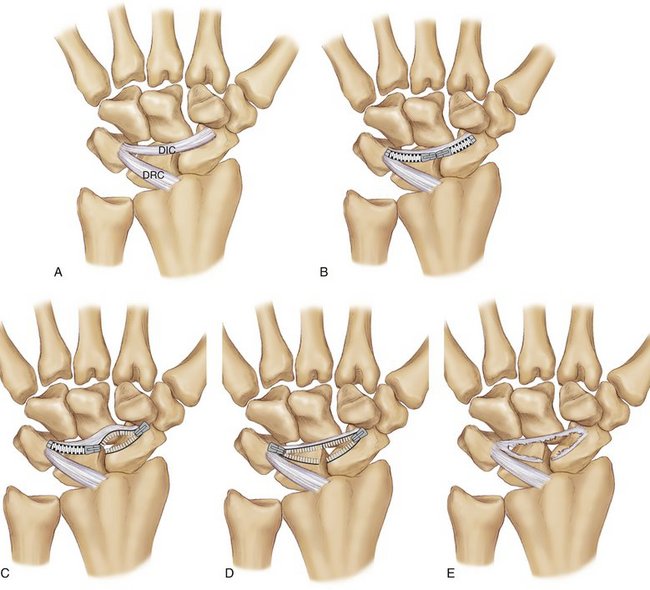

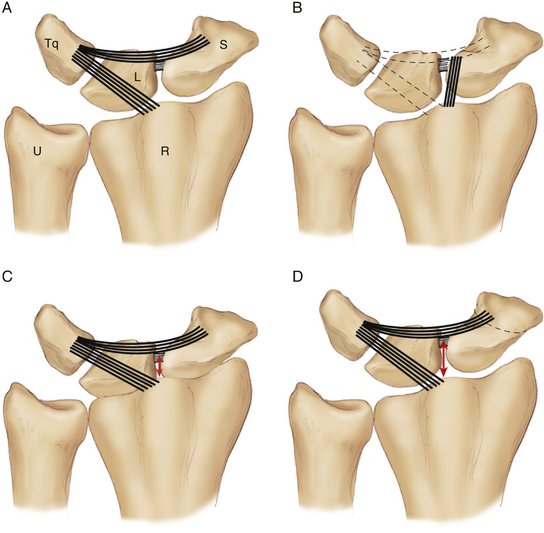

The DRC and DIC ligaments (along with the dorsal intercarpal interosseous ligaments of the proximal carpal row) form a construct that is elegant in its biomechanical design and is complex, yet simple, in its way of delivering indirect dorsal stabilization to the scaphoid at its proximal pole. The DRC and the DIC (along with the dorsal intercarpal interosseous ligaments of the proximal carpal row) together act effectively as a dorsal radioscaphoid ligament that has the ability to vary its length by changing the angle between the two arms of the lateral “V” construct formed by the DRC and DIC ligaments, while maintaining its stabilizing effect (Fig. 41-9). This lateral “V” configuration of the DRC and DIC construct allows dorsal stability of the proximal pole of the scaphoid while still allowing a threefold increase in the distance between the DRC radial attachment and the DIC scaphoid attachment (Fig. 41-10). This unique design allows dorsal stability of the scaphoid throughout the range of motion of the wrist, which would require changes in the length of a dorsal radioscaphoid ligament, if one existed or could be surgically constructed, far greater than any single fixed ligament could accommodate. To maintain the dorsal stability of the scaphoid, the DRC and the individual intercarpal components or linkages of the proximal carpal row and the DIC ligament have to maintain their integrity.

FIGURE 41-10 A, Lateral “V” configuration of the dorsal radiocarpal (parallel lines) and the dorsal intercarpal ligaments (curved lines) that function as (B) a dorsal radioscaphoid ligament (parallel black lines) while allowing (C) the linear dimensions (arrow) from the distal radius to the scaphoid to change as much as three times its length from wrist extension where the lateral V of the DRC/DIC forms a small angle to (D) wrist flexion where the lateral V of the DRC/DIC forms a large angle.

(From Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM: The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: anatomy, mechanical properties and function. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999; 24: 456-468, with permission.)

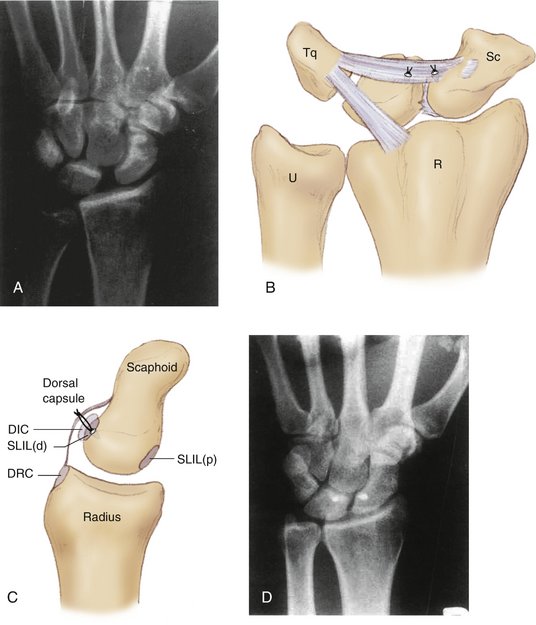

Viegas and colleagues6 report that, in the clinical setting, they have observed scapholunate dissociations in which the DIC ligament is partially (Fig. 41-11) or completely avulsed off the scaphoid. It has also been observed clinically that the dorsal SLIO and the DIC ligaments are most often avulsed off the scaphoid, rather than off the lunate. Pigeau and associates,23 using arthroscopy and CT, also found the dorsal SLIO ligament was most commonly avulsed off the scaphoid in cases of scapholunate dissociations. This coincides with the findings of the biomechanical portion of the study by Viegas and colleagues1 in which the location of failure of the DIC and the dorsal SLIO ligaments, when tested in combination, was also at the scaphoid. In some cases, the DIC has also been avulsed from its lunate attachment (Fig. 41-12), in which case the surgical repair/reconstruction should also include reattachment or reconstruction of the DIC to both the scaphoid and the lunate (Fig. 41-13). It is very important to recognize the combined role and strength of the dorsal component of the SLIO ligament complex and the DIC ligament in the function and strength of the scaphoid and lunate. In addition, the repair or reconstruction must reestablish the DIC attachments at the scaphoid and the lunate, in addition to its other attachments. Different authors6,8,17 have reported using the DIC ligament as part of the surgical repair/reconstruction in the treatment of a scapholunate dissociation. Garcia-Elias and associates have described a method of reconstructing the distal arm of the lateral “V” construct with a portion of the flexor carpi radialis tendon.24

FIGURE 41-13 A, Radiograph of a 31-year-old left-handed surgeon’s left wrist, injured in a fall he sustained while skating. He developed a painful, symptomatic scapholunate instability. B, Reconstruction of the dorsal complex and reestablishment of the indirect dorsal stability of the scaphoid using suture anchors to reattach the DIC to the lunate and to reattach the DIC and the dorsal component of the scapholunate interosseous ligament to the scaphoid from which it is often found to be avulsed in DISI injuries. C, Lateral view of a scaphoid with the suture anchor in the scaphoid showing the suture fixing first the dSLIL and DIC and then using the same suture to repair the capsule. D, Postoperative image of the patient in A who underwent the same type of repair/reconstruction.

(From Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM: The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: anatomy, mechanical properties and function. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1999; 24: 456-468, with permission.)

Previous studies of the SLIO and the LTIO ligaments have better detailed the histological and mechanical properties of the subregions of the interosseous ligaments.2–4 Both the LTIO and the SLIO ligaments have been shown by Berger and associates2–4 to have three subregions, with the central or proximal portions of both having a membranous portion that is less substantial, both histologically and mechanically, than the dorsal or volar components (Fig. 41-14). This may offer additional information to explain the mobility between the bones of the proximal carpal row, which allows for greater intercarpal motion within the proximal carpal row than within the distal carpal row. This may allow the dorsal subregions of the SLIO and the LTIO ligaments to be considered functionally as part of the dorsal ligaments and the volar subregions of the SLIO and the LTIO ligaments to be considered a part of the volar ligaments.

Mitsuyasu and coworkers25 found that complete disruption of the scaphoid from the lunate when the lunate still has an intact LTIO, and the DIC attachments to the lunate and the triquetrum are also intact, results in dynamic scapholunate instability (SLI). However, a wrist will not develop a static SLI with a DISI deformity until the DIC ligament is attenuated and/or disrupted from the lunate (Fig. 41-15). These results suggest that the treatment of SLI should address not only the SLIO ligament but also the DIC ligament at both its scaphoid and lunate attachments. Mitsuyasu and coworkers25 suggested that the role of the DIC ligament and the effect of its partial or complete disruption at the scaphoid and the lunate may be a key component in the anatomical difference between a dynamic and a static SLI with DISI. A possible explanation of why SLI can progress from a dynamic to a static instability with disruption or avulsion of the DIC off the lunate, even when all three subregions of the LTIO are intact, is because, as Ritt and colleagues5 have described, the dorsal subregion of the LTIO is weaker and less restrictive than the volar subregion. This would mean that the loss of the additional dorsal stability between the triquetrum and lunate that the DIC ligament affords would allow the lunate to assume a slightly extended posture, rotating at the more constraining volar LTIO subregion, subsequently allowing the capitate to further load the lunate into even more extension, increase the scapholunate gap, and shift the scaphoid into a flexed, dorsally subluxed posture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Kristi Overgaard for her editorial assistance and Randal Morris for his assistance with Figure 41-12, which was illustrated by Dr. Steven Viegas. This chapter was modified from Viegas SF: The dorsal ligaments of the wrist. Hand Clin. 2001; 17:65-75 with permission.

1. Viegas SF, Patterson RM, Peterson PD, et al. Ulnar-sided perilunate instability: an anatomic and biomechanic study. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1990;15:268-278.

2. Berger RA. The gross and histologic anatomy of the scapholunate interosseous ligament. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1996;21:170-178.

3. Berger RA. The ligaments of the wrist: a current overview of anatomy with considerations of their potential functions. Hand Clin.. 1997;13:63-82.

4. Berger RA, Imeada T, Berglund LJ, An KN. Constraint and material properties of the subregions of the scapholunate interosseous ligament. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1999;24:953-962.

5. Ritt MJ, Bishop AT, Berger RA, et al. Lunotriquetral ligament properties: a comparison of three anatomic subregions. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1998;23:425-431.

6. Viegas SF, Yamaguchi S, Boyd NL, Patterson RM. The dorsal ligaments of the wrist: anatomy, mechanical properties and function. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1999;24:456-468.

7. Regional Review Course in Hand Surgery. Rosemont, IL: American Society of Surgery of the Hand. 1985; 12:12-15.

8. Slater RR, Szabo RM, Bay BK, Laubach J. Dorsal intercarpal ligament capsulodesis for scapholunate dissociation: biomechanical analysis in a cadaver model. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1999;24:232-239.

9. Berger RA, Garcia-Elias M. General anatomy of the wrist. In: An KN, Berger RA, Cooney WP, editors. Biomechanics of the Wrist Joint.. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991:1-22.

10. Mizuseki T, Ikuta Y. The dorsal carpal ligaments: their anatomy and function. J Hand Surg [Br].. 1989;14:91-98.

11. Taleisnik J. The ligaments of the wrist. J Hand Surg.. 1976;1:110-118.

12. Bogumill GP. Anatomy of the wrist. In: Lichtman DM, editor. The Wrist and Its Disorders.. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988:14-26.

13. Fahrer M. Introduction to the anatomy of the wrist. In: Tubiana R, editor. The Hand.. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1981:130-135.

14. Kaplan EB, Taleisnik J. The wrist. In: Spinner M, editor. Kaplan’s Functional and Surgical Anatomy of the Hand.. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1984:154-178.

15. Mayfield JK. Wrist ligaments: anatomy and pathogenesis of carpal instability. Orthop Clin North Am.. 1984;15:209-216.

16. Mayfield JK, Williams WJ. Biomechanical properties of human carpal ligaments. Orthop Trans.. 1979;3:143-144.

17. Viegas SF. Ligamentous repair following acute scapholunate dissociation. In: Gelberman RH, editor. Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery; The Wrist.. 2nd ed. New York: Lippincott–Raven; 2000:163-175.

18. Horii E, Garcia EM, An KN, et al. A kinematic study of luno-triquetral dissociations. J Hand Surg [Am].. 1991;16:355-362.

19. Savelberg HH, Kooloos JG, Huiskes R, Kauer JM. Stiffness of the ligaments of the human wrist joint. J Biomech.. 1992;25:369-376.

20. Smith DK. Dorsal carpal ligaments of the wrist: normal appearance on multiplanar reconstructions of three-dimensional Fourier transform MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol.. 1993;161:119-125.

21. Berger RA, Bishop AT. A fiber-splitting capsulotomy technique for dorsal exposure of the wrist. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg.. 1997;1:2-10.

22. Nagao S, Patterson RM, Buford WL Jr, et al. Three-dimensional description of ligametous attachments around the lunate. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2005;30:685-692.

23. Pigeau I, Sokolow C, Romano S, Saffar P: Evaluation of scapho-lunate ligament by arthro-CT scan. Presented at the 54th annual meeting of the American Society of Surgery of the Hand in Boston, Massachusetts, September 4, 1999.

24. Garcia-Elias M, Lluch AL, Stanley JK. Three-ligament tenodesis for the treatment of scapholunate dissociation: indications and surgical technique. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2006;31:125-134.

25. Mitsuyasu H, Patterson RM, Shah MA, et al. The role of the dorsal intercarpal ligament in dynamic and static scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg [Am].. 2004;29:279-288.