The Diaphragm

Overview

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped musculofibrous membrane that separates the thoracic from the abdominal cavity. It also performs an important function in respiration. The diaphragm has a fibrous portion centrally (i.e., a central tendon) surrounded by a peripheral muscular portion. The diaphragm has three major musculofibrous groups, based on their origins: sternal, lumbar, and costal. Major structures pass through three openings: the caval opening (for the inferior vena cava and some branches of the right phrenic nerve), the esophageal hiatus (for the esophagus, anterior and posterior vagal trunks, and some small esophageal arteries), and the aortic hiatus (for the aorta, azygous vein, and thoracic duct). The diaphragm is innervated by the phrenic nerve, which is formed from the central nerves of C3, C4, and C5.1,2 Diaphragmatic lesions can arise from a variety of congenital, traumatic, infectious, and neoplastic conditions, as discussed in the following sections.

Congenital Anomalies

Duplication of the Diaphragm (Accessory Diaphragm)

Etiology: Duplication of the diaphragm, also known as an accessory diaphragm, is a rare congenital anomaly. It is almost always located on the right side and frequently is associated with lobar agenesis-aplasia complex.3,4 Although the precise pathogenesis of duplication of the diaphragm is currently unknown, it is suggested that this anomaly is the result of a defect of synchronization between the caudal migration of the septum transversum and the development of the bronchial system.3,5 Instead of developing independently, these two structures mutually interfere in each other’s growth. In gross pathology, the accessory diaphragm is a fine fibromuscular membrane with a serosal lining that is united to the anterior part of the diaphragm.3 It follows a posterosuperior direction to join the posterior chest wall, separating the right hemithorax into two parts.3,4 It is crescentic in form and usually has an opening (i.e., central hiatus) medially, through which vessels and bronchial structures pass. Affected patients may be asymptomatic, but most present with respiratory difficulties of varying degrees.5

Imaging: On chest radiographs or computed tomography (CT), the accessory diaphragm may have two different appearances.3 When the central hiatus is markedly narrowed and the trapped lung is not aerated, it appears like a mass. However, when the trapped lung is aerated, the accessory diaphragm is seen as a fissurelike structure in the right base extending from the anterior aspect of the hemidiaphragm cephalad toward the posterior chest wall. On CT, it is seen as a bandlike structure with crowding of pulmonary structures as the bronchi and vessels traverse the central hiatus (Fig. 61-1).4,5

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

Traditionally, congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDHs) have been classified according to their anatomic location. Almost 90% of CDHs are reported to involve the posterolateral aspect of the diaphragm and are referred as to Bochdalek hernias.6 Nonposterolateral CDHs occur most often in the anterior portion of the diaphragm and are known as Morgagni hernias. However, diaphragmatic defects do not exclusively localize to these two areas, and thus some defects do not follow this classification. To further complicate the classification, some diaphragmatic hernias have a sac, which is thought to represent focal thinning of the diaphragmatic musculature. Thus the terms sac hernia and eventration currently are poorly defined. Despite its limitations, an anatomic-based classification system continues to be used (Box 61-1).6

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia: Bochdalek

Etiology: CDH of the Bochdalek type is a birth defect that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.7 The average prevalence of CDH, derived from a meta-analysis of 16 population-based studies, is 1 in 4000 births.7 The Bochdalek hernia is the most common subtype, accounting for approximately 90% to 95% of all CDHs.6 Approximately 85% of these hernias occur on the left side, whereas right-sided and bilateral hernias represent only 13% and 2% of cases, respectively.8 Bochdalek hernias can be divided into two main categories—isolated and complex—based on the presence of additional associated malformations.6

The underlying pathogenesis of CDH is poorly understood. However, much more is currently known about the cellular events and molecular cues that control early differentiation of the diaphragm. The diaphragm initially develops as a septum between the heart and the liver, progresses posterolaterally, and closes at the Bochdalek foramen at approximately 8 to 10 weeks of gestation.8,9 Studies have suggested that the primary abnormality resulting in a Bochdalek hernia is failure or delay of the pleuroperitoneal fold and transverse septum to properly fuse with the intercostal muscles around the eighth week of gestation.9 More recent evidence suggests that a diaphragmatic hernia and lung hypoplasia are associated, but they may not be causally related.8

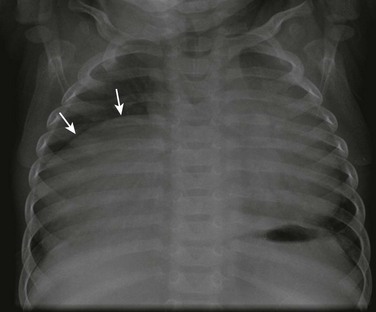

Imaging: A Bochdalek hernia may appear at birth as an opacified hemithorax with contralateral cardiomediastinal shift. As the infant swallows air, the air-filled gut located within the hemithorax may become apparent (Fig. 61-2). In the case of intraabdominal solid organ herniation such as the liver and spleen, the hemithorax can remain homogeneously opacified. When large and with herniation of the bowel, a paucity of air in the abdomen causing the so-called “scaphoid abdomen” can be seen on abdominal radiographs.9 The position of catheters and tubes is helpful in confirming the presence of a Bochdalek hernia. The nasogastric (NG) tube deviates to the side opposite to the hernia in the chest. If the stomach is herniated within the hemithorax, the tip of the NG tube can project in the chest. The position of umbilical venous catheters also is affected according to the location of the liver, which is shifted either in the abdomen or chest. In contrast, the position of umbilical arterial catheters is rarely affected because of their retroperitoneal location.10 In the postoperative period, an ipsilateral pneumothorax is a common finding and should not be rapidly evacuated. A rapid evacuation of a pneumothorax in this situation may cause mediastinal rotation and subsequent venae cavae obstruction because of the increased mobility of the neonatal mediastinum.9 The pleural air subsequently reabsorbs by itself and sometimes is replaced by fluid. Ultrasound with color Doppler may help delineate the venae cavae and the hepatic vasculature, and it may identify the presence of herniated solid organs before surgery. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may play an occasional role in excluding a congenital lung anomaly such as congenital pulmonary airway malformation or pulmonary sequestration.9

Treatment and Follow-up: Treatment of all types of CDH, including the Bochdalek hernia, can be classified into medical or surgical management. The medical management of CDH focuses on addressing the underlying major causes of neonatal death as a result of CDH, such as pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary hypertension. It includes the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, high-frequency ventilation, and inhaled nitric oxide.11–13 Surgical repair of CDH is performed with a transabdominal or transthoracic approach, and more recently, surgery is performed laparoscopically or thoracoscopically. The herniated abdominal viscera are removed from the chest and repositioned in the abdomen. The posterolateral diaphragmatic defect is usually closed with nonabsorbable sutures if the defect is small or with a prosthetic patch if the defect is larger than 5 cm.14 Currently no specific guideline exists for following up on children with a repaired CDH. However, chest radiographs often are obtained routinely for confirmation of an intact diaphragm and early detection of a possible CDH recurrence. On follow-up chest radiographs, abnormalities including persistent lung hypoplasia, decreased pulmonary vascularity, and mediastinal shift may be observed.

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia: Morgagni

Etiology: The foramen of Morgagni is an anterior opening in the diaphragm that extends between the sternum medially and the eighth rib laterally. In Morgagni hernias, also known as retrosternal hernias, the underlying congenital defect results from developmental failure of the fibrotendinous elements of the sternal part of the diaphragm to fuse with the costal part.15–17 They account for 9% to 12% of the diaphragmatic defects in infancy. These hernias usually are unilateral and are right sided in 90% of cases.9 A Morgagni hernia may occur as one of the components of the pentalogy of Cantrell, which is characterized by omphalocele, anterior diaphragmatic hernia, sternal cleft, ectopia cordis, and intracardiac defect such as a ventricular septal defect or a diverticulum of the left ventricle.9,17 A Morgagni hernia can be seen in association with congenital heart disease, intestinal malrotation, and chromosomal abnormalities, most frequently Down syndrome.9,17

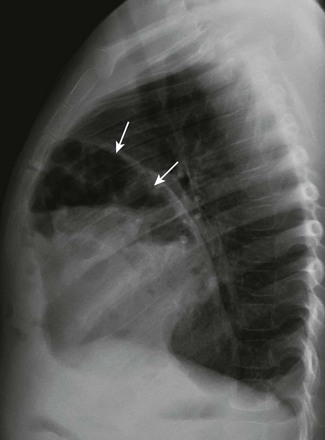

Imaging: Most cases of Morgagni hernias are discovered incidentally on chest radiographs that are obtained for evaluation of other conditions in older children and adults. On chest radiographs, the diagnosis is made when anterior herniation of bowel loops is identified on the lateral chest radiograph (Fig. 61-3). When solid organs such as the liver or spleen are involved, the appearance may not be specific and can resemble focal diaphragmatic eventration, lymphadenopathy, or a foregut duplication cyst. Ultrasound, CT, or MRI can be helpful in the diagnosis when solid organs are herniated.9,16,17

Treatment and Follow-up: The current treatment of choice for a Morgagni hernia is surgical repair at the initial diagnosis, even in the absence of symptoms, because of the increased risk of developing bowel obstruction and subsequent incarceration. Most Morgagni hernias can be repaired laparoscopically.1,9,16

Delayed Presentation of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

Etiology: Approximately 5% to 20% of pediatric patients may present with a delayed CDH.18 Although currently it is not clear whether the diaphragmatic defect in these patients is congenital or acquired, it has been assumed that the defect may have been present prenatally but was either small or temporarily occluded by solid organs such as the liver or spleen.18,19 In a recent multicenter retrospective study by the Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group,19 the location, male/female ratio, birth weight, and gestational age all were similar between children with neonatal CDH and infants or children with delayed presentation of CDH. These findings support the assumption that the defect of late-presenting CDH is most likely congenital in nature. Because of the widely varied presenting symptoms and the rarity of this entity, the diagnosis of late-presenting CDH may be delayed or missed.20,21

Delayed presentation of a diaphragmatic hernia can be categorized into two groups: (1) infants who present with respiratory symptoms and (2) older children who present with gastrointestinal symptoms. Infants with delayed presentation of CDH usually present in the first few months of life. It often is associated with right-sided pneumonia caused by group B streptococcal infection and initially may be obscured by the consolidative changes. In contrast, the larger group of older children often present with a history of abdominal pain or recurrent vomiting later in life. Approximately two thirds of this delayed presentation of CDH occurs on the posterolateral right side (i.e., Bochdalek). Asymptomatic cases discovered incidentally also occur.18–21

Imaging: Several studies have shown that delayed presentation of a CDH often can be missed on initial chest radiographs.18,20 The chest radiograph of a neonate with this type of hernia may be normal in the neonatal period. When only solid organs are herniated, a homogeneous opacity may be seen. Unfortunately, such opacity can be confused with pneumonia or a pleural effusion (Fig. 61-4). In the case of a herniated bowel, tubular air-filled, radiolucent structures projecting into the chest may mimic pneumatoceles or a pneumothorax. Such situations may cause mismanagement such as insertion of a chest tube, which is associated with a potential risk of gastrointestinal perforation or bleeding. A gas-filled herniated stomach may mimic a pneumothorax or a lung abscess. A delayed presentation of an anteriorly located Morgagni hernia, if it is not gas filled, may simulate cardiomegaly or a mediastinal mass.18–21 A chest radiograph after insertion of an NG tube has been shown to be the most useful imaging study in confirming a late-presenting hernia.22 Not infrequently, chest radiography is supplemented by other diagnostic modalities aimed at confirming the hernia. An upper gastrointestinal study can be useful if it demonstrates the presence of bowel in the chest; however, it may yield false negative results in cases of exclusive solid organ herniation. To correctly diagnose a hernia containing only large bowel, it is important to obtain a delayed image during an upper gastrointestinal study. Ultrasound is particularly useful for patients with intrathoracic herniation of only solid organs, or when the hernia mimics a pleural effusion. CT or MRI has the advantage of demonstrating the diaphragmatic defect and herniating mesentery and bowel.18,21

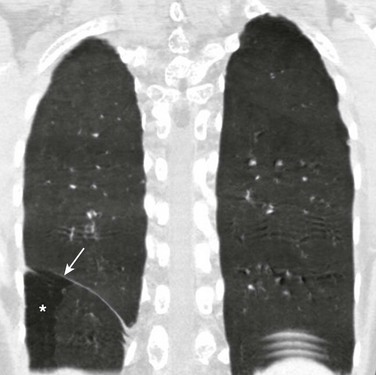

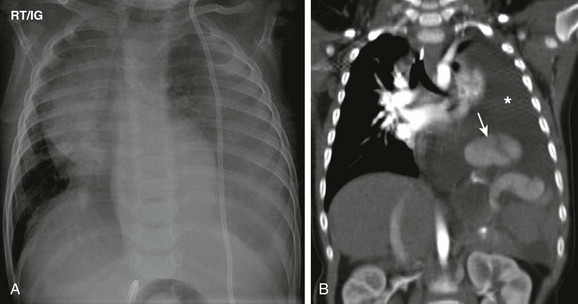

Figure 61-4 A late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in a 16-month-old boy with shunted hydrocephalus and vomiting.

A, A frontal chest radiograph shows an opacity in the left hemithorax without clear visualization of the left hemidiaphragm. Cardiomediastinal shift to the right side is also present. Note a left shunt catheter. B, A coronal soft tissue window computed tomography image shows a left pleural effusion (asterisk) and herniated spleen (arrow) into the left hemithorax and poor visualization of the left hemidiaphragm. The left pleural effusion was attributed to a malfunctioning shunt catheter.

Treatment and Follow-up: The treatment of delayed diaphragmatic hernia is surgical, with repositioning of the herniated organs in the abdomen and primary closure of the defect or placement of mesh to patch the defect when it is large. The outcome is generally favorable, but misdiagnosis may result in significant morbidity or death. Gastrointestinal obstruction with visceral incarceration is a possible presentation beyond the neonatal period. The role of routine follow-up chest radiographs after surgical repair currently is unclear; however, it may be beneficial for assessing possible recurrence rather than evaluating underlying pulmonary hypoplasia.20,23

Eventration

Etiology: Diaphragmatic eventration is defined as an abnormal elevation of all or a portion of an attenuated but otherwise intact diaphragmatic leaf. It may be congenital or may develop as a result of paralysis, with the former situation being more common. Congenital diaphragmatic eventration occurs when the fetal diaphragm fails to muscularize, leaving a layer of pleura and peritoneum in that region.1,24 Among cases that develop as a result of paralysis, diaphragmatic eventration has been described in association with poliomyelitis, herpes zoster, diphtheria, lead poisoning, various infections, and infantile cortical hyperostosis. It can be focal or diffuse, with the former presentation being more common. The focal type of diaphragmatic eventration frequently occurs anteromedially on the right side, and the diffuse type occurs on the left side.16 Pediatric patients with focal diaphragmatic eventration usually are asymptomatic. With diffuse eventration, symptoms of respiratory insufficiency are seen more frequently in newborns and infants because of a mobile mediastinum causing pulmonary and venous compression by the elevated viscera.16,17,25

Imaging: Focal diaphragmatic eventration, which is a common incidental finding on a chest radiograph, appears as a focal diaphragmatic bulge in the anteromedial side of the right hemithorax (Fig. 61-5).16,17 Radiographs may show the elevated diaphragm, allowing distinction in some cases from CDH, in which the diaphragm is in a normal position but the intestinal contents have herniated through an opening in the diaphragm.16,20 After chest radiographs are obtained, ultrasound can be used to exclude a possible underlying mass and also to evaluate the diaphragmatic mobility using M-mode.17 Total eventration of the diaphragm in older children and adults often is indistinguishable from diaphragmatic paralysis on chest radiographs. A helpful differentiating sign is that an eventration typically will not have adjacent areas of atelectasis, whereas paralysis of the diaphragm will have such areas. During fluoroscopy, an eventrated diaphragm typically displays an inspiratory lag followed by delayed downward motion. However, slight paradoxic movement, little movement, or no movement may occur in cases of an eventrated diaphragm, which sometimes makes the distinction from paralysis challenging.16,17

Treatment and Follow-up: A focal diaphragmatic eventration usually requires no treatment or follow-up because it is usually of no clinical significance. In pediatric patients with a focal diaphragmatic eventration that causes respiratory distress, eventration is plicated. Plication involves a folding and subsequent suturing of the eventrated diaphragm to reduce the excess diaphragmatic tissue. Although surgical techniques of diaphragmatic plication technically are relatively simple, the indication and the timing of surgery are still somewhat controversial.1,25

Diaphragmatic Injuries

Etiology: Injury or abnormality of the phrenic nerve leading to diaphragmatic motion abnormalities may occur unilaterally or bilaterally as a result of birth trauma or after surgical interventions, most commonly cardiac surgery.2 The prevalence of diaphragmatic paralysis is 0.03% to 0.5%.2 The prevalence following thoracic surgery in children has been reported to range between 0.5% and 10%.2,26–28 In infants, diaphragmatic paralysis may result in life-threatening respiratory insufficiency and ventilatory failure. Unexplained difficulty in weaning a patient from mechanical ventilation or an increasing oxygen requirement should raise the suspicion of diaphragmatic paralysis.17,27

Imaging: Several imaging modalities have been used to diagnose diaphragmatic paralysis. Diaphragmatic paralysis usually is suggested on chest radiographs when they show persistent elevation of the affected hemidiaphragm. However, the position of the diaphragm may not be reliable in the newborn period. Fluoroscopic assessment of diaphragmatic motion, which previously was the gold standard, largely has been replaced by ultrasound. Ultrasound with the use of M-mode is superior to fluoroscopy in the evaluation of the diaphragm because of its portability, lack of ionizing radiation, and ability to visualize the entire diaphragm (Fig. 61-6).27 Diaphragmatic movement is considered normal if the diaphragm moves toward the transducer during inspiration, with excursion of greater than 4 mm and a difference in excursion between the domes of less than 50%.16,17,26–28

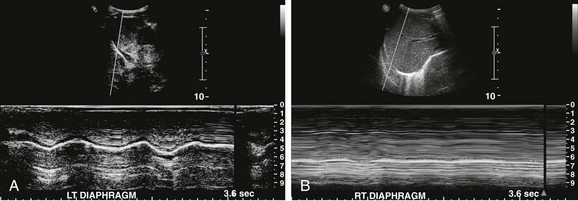

Figure 61-6 Diaphragmatic paralysis in a 10-month old boy after tetralogy of Fallot repair who was unable to be weaned from the ventilator.

A, An ultrasound image using M-mode of the left hemidiaphragm reveals a normal diaphragmatic waveform. B, An ultrasound image using M-mode of the right hemidiaphragm reveals a flat waveform, indicating paralysis.

Treatment and Follow-up: The initial treatment of patients with diaphragmatic paralysis is supportive, which includes positioning the affected patients ipsilateral to the affected side and providing oxygen and mechanical ventilation in cases of respiratory failure.2,29 After 30 days of unsuccessful noninvasive treatment, plication usually is needed, especially in patients younger than 1 year and those with iatrogenic injuries of the phrenic nerve.1,2,17,30

Diaphragmatic Rupture

Etiology: Diaphragmatic rupture, which is rare in children, typically occurs after a blunt or penetrating trauma. In a large study of 20,500 pediatric trauma patients, the incidence of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture was found to be 0.07%, with a mean age of 7.5 years.31 It was slightly more frequent in boys and occurred more commonly as a result of blunt, rather than penetrating, trauma.31 Associated injuries such as a head injury, pelvic fractures, and splenic and renal injuries are common. However, isolated diaphragmatic injuries have been reported more often in children than in adults. Diaphragmatic rupture is more common on the left than on the right. The left-sided predominance probably is the result of a protective effect by the liver on the right diaphragm.32 Because of its rarity, the correct diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture often is delayed or missed, often leading to intestinal obstruction and subsequent bowel ischemia.31

Imaging: Diaphragmatic rupture in children is difficult to detect clinically and on imaging, and it requires a high index of suspicion.31–33 Several studies show that chest radiographs have suggestive findings in 64% to 77% of cases; however, they are diagnostic in only 25% to 50% of cases.33 Nonspecific but suggestive imaging findings of diaphragmatic rupture on chest radiographs include (1) an archlike soft tissue opacity in the lower chest; (2) unusual densities or gas bubbles resulting from bowel herniation; and (3) atelectasis, pleural effusions, and a mediastinal shift to the nonaffected side.33 Imaging findings considered diagnostic of a diaphragmatic rupture after trauma are the presence of herniated abdominal organs (e.g., bowel loops or solid organs) and an NG tube in the chest (Fig. 61-7).33 CT, especially coronal reformations, may confirm the diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture by showing irregularity and thickening of the diaphragmatic leaflet and herniated abdominal organs.32,33 Fluoroscopy and contrast studies have limited use in the acute setting.34

Figure 61-7 Diaphragmatic rupture in a 5-year-old boy who fell from playground equipment.

An abdominal radiograph shows obliteration of the left hemidiaphragm with soft tissue and lucencies projecting in the left base. The tip (arrow) of a nasogastric tube projects in the chest, confirming a left diaphragmatic rupture. The hyperdensity in the right flank is due to perinephric intravenous contrast extravasation as a result of a shattered kidney (asterisk).

Treatment and Follow-up: The treatment of diaphragmatic rupture is surgical, whether the patient presents in the acute or delayed setting. Repair of the acute traumatic diaphragmatic rupture is directed by other injuries that may be present. Small defects are repaired by direct suturing, whereas larger defects are patched with mesh.1,32 Although fluoroscopy plays little role in the preoperative diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture, it can be useful in assessing the diaphragm after repair to evaluate diaphragmatic motion and hernia recurrence.

Diaphragmatic Neoplasms

Etiology: Primary diaphragmatic tumors are very rare.17 In a study by Cada et al,34 41 cases were found in patients younger than 18 years with equal gender frequency and a mean age at diagnosis of 10 years. Most diaphragmatic tumors are malignant, with rhabdomyosarcoma being the most common tumor found in the diaphragm.17,35 Other primary diaphragmatic malignant tumors in children are undifferentiated sarcomas, germ cell tumors, and the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors.17,35–37 Secondary involvement of the diaphragm by adjacent malignant tumors also can occur.17,35 Benign tumors include neurofibromas, lipomas, myofibroblastic tumors, and hemangiomas.17 Cystic lesions (not necessarily neoplasms) involving the diaphragm include mesothelial cysts, bronchogenic cysts, cystic teratomas, and hydatid cysts.17,38

Affected patients—especially those with benign lesions—usually are asymptomatic, and the diagnosis of diaphragmatic neoplasm is made incidentally as part of unrelated imaging, at surgery, or even at autopsy. Patients with a large or malignant diaphragmatic tumor usually present with symptoms such as chest pain, cough, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, and dysphagia.17,35,37 An exophytic, large diaphragmatic tumor also may be palpable on physical examination.

Imaging: The greatest challenge in assessing a diaphragmatic tumor is determining its exact site of origin. Especially on right-sided lesions, the site of origin frequently has been mistakenly assigned to the liver. No single imaging modality has demonstrated superiority in diagnosing diaphragmatic tumors, and frequently a combination of ultrasound, CT, and MRI is necessary for a correct diagnosis.17,35 The majority of malignant tumors present as large masses with advanced local disease or metastasis to the pleura and lung.36 The claw sign, the pattern of organ displacement, and the presence of an obtuse angle between the tumor and the diaphragm may help determine diaphragmatic origin (Fig. 61-8).35 Not infrequently, the diaphragmatic origin of the tumor becomes more evident after size reduction following chemotherapy. In cases of a palpable mass or a mass seen on chest or abdominal radiographs, ultrasound may be the initial study of choice to begin the investigation. Ultrasound can confirm the presence of a mass and excludes the presence of a pleural effusion, which is one of main differential diagnostic considerations. To further evaluate the precise extent of the mass, including invasion to adjacent organs, cross-sectional imaging studies such as CT or MRI with two-dimensional and three-dimensional reconstructions can be of great value.35

Treatment and Follow-up: After imaging studies, a definitive diagnosis of diaphragmatic tumors can be made on the basis of histopathological evaluation of a biopsy specimen. Once a histopathological diagnosis is made, chemotherapy usually is instituted to reduce the size before surgical resection. Adjuvant preoperative radiation therapy may help in cases of infiltrative tumors. Germ cell tumors may go into remission after chemotherapy because of their high chemosensitivity.17,35,36

Baglaj, M, Dorobisz, U. Late presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in children: a literature review. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:478–488.

Chavhan, GB, Babyn, PS, Chohen, RA, et al. Multimodality imaging of the pediatric diaphragm: anatomy and pathologic conditions. Radiographics. 2010;30:1797–1817.

Mata, JM, Caceres, J. The dysmorphic lung: imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:403–414.

Ramos, CT, Koplewitz, BZ, Babyn, PS, et al. What have we learned about traumatic diaphragmatic hernias in children? J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:601–604.

Schumpelick, V, Steinau, G, Schluper, I, et al, Surgical embryology and anatomy of the diaphragm with surgical applications. Surg Clin North Am, 2000;80:213–239.

References

1. Maish, MS. The diaphragm. Surg Clin N Am. 2010;90:955–968.

2. Schumpelick, V, Steinau, G, Schlüper, I, et al. Surgical embryology and anatomy of the diaphragm with surgical applications. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:213–239.

3. Hidalgo, A, Franquet, T, Gimenez, A. 16-MDCT and MR angiography of accessory diaphragm. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:149–152.

4. Mata, JM, Caceres, J. The dysmorphic lung: imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:403–414.

5. Pober, BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects and chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145C:158–171.

6. Skari, H, Bjornland, K, Haugen, G, et al. Congential diaphragmatic hernia: a meta-analysis of mortality factors. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1187–1197.

7. Keijzer, R, Puri, P. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19:180–185.

8. Taylor, GA, Omolola, MA, Estroff, JA. Imaging of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:1–16.

9. Sakurai, M, Donnelly, LF, Klosterman, LA, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in neonates: variations in umbilical catheter and enteric tube position. Radiology. 2000;216:112–116.

10. Hotlz, PD, Arkovits, MS, Berdon, WE, et al. Newborns with diaphragmatic hernia: initial chest radiography does not have a role in predicting clinical outcome. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:462–464.

11. Morini, F, Goldman, A, Piero, A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a systematic review of the evidence. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006;16:385–391.

12. Chao, P-H, Huang, C-B, Liu, C-A, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the neonatal period: review of 21 years’ experience. Pediatr Neonatal. 2010;51:97–102.

13. Shah, SR, Wishnew, J, Barsness, K, et al. Minimally invasive congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: a 7-year review of one institution’s experience. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1265–1271.

14. Bagolan, P, Morini, F. Long-term follow up of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16:134–144.

15. Roberts, HC. Imaging the diaphragm. Thorac Surg Clin. 2009;19:431–450.

16. Chavhan, GB, Babyn, PS, Chohen, RA, et al. Multimodality imaging of the pediatric diaphragm: anatomy and pathologic conditions. Radiographics. 2010;30:1797–1817.

17. Baglaj, M, Dorobisz, U. Late presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in children: a literature review. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:478–488.

18. The Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Late presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1839–1843.

19. Elhalaby, EA, Abo Sikeena, MH. Delayed presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Surg. 2002;18:480–485.

20. Cigdem, MK, Onen, A, Otcu, S, et al. Late presentation of Bochdalek-type congential diaphragmatic hernia in children: a 23-year experience at a single center. Surg Today. 2007;37:642–645.

21. Berman, L, Stringer, D, Ein, SH, et al. The late-presenting pediatric Bockdalek hernia: a 20-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;27:1225–1228.

22. Anaya, J, Naik-Mathuria, B, Olutoye, OO. Delayed presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia manifesting as combined-type acute gastric volvulus: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:E35–E39.

23. Groth, SS, Andrade, RS. Diaphragmatic eventration. Thorac Surg Clin. 2009;19:511–519.

24. Yazici, M, Karaca, I, Arikan, A, et al. Congenital eventration of the diaphragm in children: 25 years experience in three pediatric surgery centers. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:298–301.

25. Oh, A, Gulati, G, Sherman, ML, et al. Bilateral eventration of the diaphragm with perforated gastric volvulus in an adolescent. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1824–1826.

26. Epelman, M, Navarro, OM, Daneman, A, et al. M-mode sonography of diaphragmatic motion: description of technique and experience in 278 pediatric patients. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:661–667.

27. Urvoas, E, Pariente, D, Fausser, C, et al. Diaphragmatic paralysis in children: diagnosis with TM-mode US. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:564–568.

28. Celli, BR. Respiratory management of diaphragmatic paralysis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;23:275–281.

29. Toenz, M, von Segesser, LK, Mihaljevic, T, et al. Clinical implication of phrenic nerve injury after pediatric cardiac surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1265. [abstract].

30. Ramos, CT, Koplewitz, BZ, Babyn, PS, et al. What have we learned about traumatic diaphragmatic hernias in children? J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:601–604.

31. Shehata, SM, Shabaan, BS. Diaphragmatic injuries in children after blunt abdominal trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1727–1731.

32. Koplewitz, BZ, Ramos, C, Manson, DE, et al. Traumatic diaphragmatic injuries in infants and children: imaging findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30:471–479.

33. Iochum, S, Ludig, T, Walter, F, et al. Imaging of diaphragmatic injury: a diagnostic challenge. Radiographics. 2002;22(suppl):S103–S116. [discussion S116-S118].

34. Cada, M, Gerstle, JT, Traubici, J, et al. Approach to diagnosis and treatment of pediatric primary tumors of the diaphragm. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1722–1726.

35. Raney, RB, Anderson, JR, Andrassy, RJ, et al. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the diaphragm: a report form the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group from 1972-1997. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:510–514.

36. Traubici, J, Daneman, A, Hayes-Jordan, A, et al. Primary germ cell tumor of the diaphragm. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1578–1580.

37. Esparza, EJ, Gonzalez, AA, Saenz Banuelos, J. Radiological appearance of diaphragmatic mesothelial cysts. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:855–858.

38. Akinci, D, Akhan, O, Ozmen, M, et al. Diaphragmatic mesothelial cysts in children: radiologic findings and percutaneous ethanol sclerotherapy. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:873–877.