CHAPTER 63 THE DIAGNOSIS OF VASCULAR TRAUMA

The diagnosis of vascular trauma is usually not a problem, as most injuries manifest overt blood loss, shock, or loss of critical pulses. However, in certain instances, the lesion may not be recognized initially, only to manifest itself later by sudden secondary hemorrhage or the development of critical organ or extremity ischemia.

HARD AND SOFT SIGNS OF VASCULAR INJURY

On the basis of history and physical examination, manifestations of vascular injury can be classified into two general prognostic categories, hard signs and soft signs (Table 1).

| Hard Signs | Soft Signs |

|---|---|

| Active arterial bleeding | Neurologic injury in proximity to vessel |

| Pulselessness/evidence of ischemia | Small- to moderate-sized hematoma |

| Expanding pulsatile hematoma | Unexplained hypotension |

| Bruit or thrill | Large blood loss at scene |

| Arterial pressure index <0.90 pulse deficit | Injury (due to penetrating mechanism, fracture, or dislocation) in proximity to major vessel |

From Anderson JT, Blaisdell FW: Diagnosis of vascular trauma. In Rich N, Mattox KL, Hirshberg A, editors: Vascular Trauma, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier/Saunders, 2004.

Hard signs are strong predictors of the presence of an arterial injury and the need for urgent operative intervention. Obvious examples include bright red pulsatile bleeding or a rapidly expanding hematoma. Evidence of extremity ischemia (manifested by the six P’s—pulselessness, pallor, pain, paralysis, paresthesia, and poikilothermia) and a bruit or thrill are additional examples. For extremity trauma, we also consider an arterial pressure index (API), also known as the ankle-brachial index, of less than 0.90 to be a hard sign. The API is determined by dividing the systolic pressure of the injured limb by the systolic pressure of the noninjured limb. Johansen and colleagues1 demonstrated 95% sensitivity and 97% specificity for identification of occult arterial injury with an API of less than 0.90. An API of more than 0.90 had a 99% negative predictive value for the presence of an arterial injury. The API is readily determined at bedside, and should be considered an extension of the physical examination. An important caveat is that the API may be normal in nonconduit vessels such as the profunda femoris.

Soft signs are those suggestive of an arterial injury, although with a much decreased likelihood than hard signs (see Table 1). These consist of mild pulse deficits, soft bruits, nonexpanding hematomas, and fractures or wounds in close proximity to major vessels. The actual incidence of arterial injury with these findings varies. For instance, patients with injury in proximity to a major vessel as the only finding are found to have an identifiable injury in less than 10% of cases; further, many of these injuries do not require additional treatment beyond simple observation. Most of the controversy of vascular trauma evaluation revolves around the assessment of patients with soft signs.

ADDITIONAL ANCILLARY TESTS

Duplex ultrasonographic scanning combines two-dimensional imaging to assess anatomic detail and Doppler insonation to assess flow characteristics. Several investigators have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in the detection of vascular injury in various anatomic locations.2–5 Duplex ultrasonography is more sensitive to the presence of vascular injury than the arterial pressure index (API). Importantly, duplex ultrasonography can identify arterial injuries in nonconduit vessels such as the profunda femoris (the API will remain normal). However, duplex ultrasonography is limited, as it is technician dependent and in most centers is not readily available after hours.

Recently, there has been a groundswell of interest in the use of CT angiography as a diagnostic modality for vascular injury in multiple anatomic locations.6–11 Major advantages include almost universal availability and three-dimensional (3D) detail. Compared with formal angiography, an interventional radiologist does not need to be in attendance at the time of the examination. In general, the examination can be obtained more expeditiously than formal angiography, particularly after hours. Technological advancements in imaging resolution and software have been significant. Arterial anatomy can be reconstructed in 3D detail for easy evaluation. However, the modality is diagnostic only. A subsequent angiogram may be required for therapeutic embolization. Notably, the combined contrast load from both a CT angiogram and a subsequent angiogram can be significant. An additional technical limitation is that CT angiography is compromised by scatter from metallic fragments much more than formal angiography.12 CT angiography is of particular value when thoracic vascular injury is suspected, and it has proven to be a highly sensitive screening test.13 However, mediastinal hematoma alone, without evidence of arterial disruption, may still require arteriography to confirm large vessel injury.14

Arteriography has long been regarded the gold standard for assessment of arterial injury.15 It is well tolerated and has a low complication rate. Major complications such as iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm or AV fistulas are very uncommon in the young population typical of most trauma centers. A major advantage of arteriography is the availability of therapeutic options (such as embolization). Further, compared with CT angiography, formal arteriography is not prone to scatter from the presence of metallic fragments. Even in centers that rely on CT imaging as the predominant diagnostic study, formal arteriography still has a diagnostic role in confirming or further delineating the presence of equivocal CT findings. This latter point is particularly applicable in the assessment of carotid injuries where even minor injuries may be of importance. An occasional patient requires urgent operation before availability of formal arteriography or CT angiography. In these patients, an on-table, surgeon-performed arteriogram can be obtained in the operating room. For instance, a femoral artery can be cannulated with an arterial catheter, contrast injected, and images obtained either with plain films or fluoroscopy.16–19 O’Gorman and colleagues16,17 have demonstrated that the axillary artery can be visualized by injection of contrast into the brachial artery with distal outflow occlusion with a blood pressure cuff inflated to a level well beyond the systolic arterial blood pressure. A benefit of the recent popularity of endovascular techniques has been increased availability of formal arteriography in the operating room. In fact, some centers have the capability of embolization of pelvic or visceral vessels in the operating room, thereby precluding the need to transport an unstable patient to a radiology suite that may not have the resources of the operating room.

SPECIFIC AREAS OF INJURY

Cervical vascular trauma may be manifested by initial signs of external hemorrhage, expanding hematoma16 or ipsilateral hemispheric ischemic symptoms, including hemiplegia, hemiparesis, or monocular blindness. The latter neurologic symptoms must be assumed to result from carotid artery interruption or thrombosis until proven otherwise. Deficits resulting from cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and/or XII suggest the possibility of vascular injury because of their immediate proximity to the carotid artery and the jugular vein. Penetrating trauma is associated with hemorrhage or false aneurysms, whereas blunt trauma invariably produces symptoms through thrombosis. This can be either immediate or delayed. In cases of major neck trauma, duplex scanning has greatly facilitated screening for intimal disruption or dissection, and some institutions use it liberally. CT angiography has recently been established as a viable alternative to formal angiography in the screening of blunt carotid injury as well as in the assessment of penetrating neck injury.8,9,11, Formal angiography should still be considered the gold standard, and is required in equivocal cases as well as the occasional patient who requires embolization of a disrupted vertebral artery.

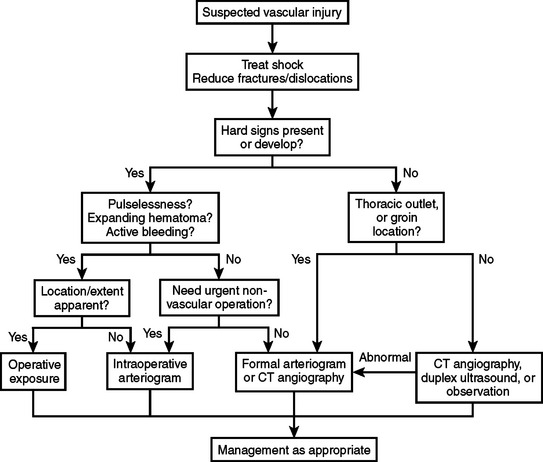

Extremity vascular injuries lend themselves to the diagnostic and screening maneuvers described in the previous sections. These patients fall into three general categories: (1) patients with evidence of pulselessness/ischemia, active bleeding, or a pulsatile hematoma; (2) patients with hard signs and a palpable pulse; and (3) patients with soft signs or an injury known to be associated with vascular injury. Initially, all patients should be adequately resuscitated and undergo reduction and stabilization of associated dislocations and fractures. Perfusion should be reassessed after these initial measures. In some cases, perfusion normalizes, and subsequent workup can proceed more deliberately. Ongoing assessment of patients with suspected extremity vascular injuries is outlined in Figure 1 and in the following discussion.

Figure 1 Algorithm: evaluation of extremity trauma.

(Modified from Anderson JT, Blaisdell FW: Diagnosis of vascular trauma. In Rich N, Mattox KL, Hirshberg A, editors: Vascular Trauma, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier/Saunders, 2004.)

In the first category, patients with evidence of pulselessness/ischemia, active bleeding, or a pulsatile hematoma, urgent attention is required to prevent exsanguination or tissue necrosis from ischemia. Generally, these patients should be taken promptly to the operating room. If ischemia is complete, such as with a tourniquet, muscle necrosis will result from 4 hours of ischemia; fortunately, there is often some collateral flow that extends this critical time period. In most cases, the location of injury is apparent from the history, physical, and preliminary plain films; operative intervention can proceed accordingly. In other situations, the exact location and degree of injury are not apparent (Table 2). To minimize the duration of warm ischemia, on-table angiography can be performed. In some centers, formal angiography is available in the operating room.

From Anderson JT, Blaisdell FW: Diagnosis of vascular trauma. In Rich N, Mattox KL, Hirshberg A, editors: Vascular Trauma, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier/Saunders, 2004.

The final category involves patients with suspected extremity vascular injuries who present with soft signs only. Much of the controversy regarding evaluation of vascular trauma concerns this category. In patients with an injury in proximity to a major artery (although without hard signs), radiologic abnormalities may be present in as many as 10% of patients who undergo arteriography. However, a much smaller proportion of patients require operative intervention—several series indicate a range of 0.6%–4.4% of patients. Dennis and colleagues have made a cogent argument in support of physical examination alone in this patient population.20 They argue that patients requiring operative intervention will be identified from subsequent development of hard signs. Typically, patients are admitted for a short period of observation. Concerns regarding poor patient compliance for follow-up and a push to expeditiously identify significant injuries early (ideally, shortly after presentation to the emergency room to guide appropriate disposition) have led many others to use alternative protocols involving ultrasonography or CT imaging. Ultimately, the choice is often determined by cost, availability of modalities, center volume/resources, and local expertise.

1 Johansen K, Lynch K, Paun M, Copass M. Non-invasive vascular tests reliably exclude occult arterial trauma in injured extremities. J Trauma. 1991;31(4):515-519. discussion 519–522

2 Fry WR, Smith RS, Sayers DV, et al. The success of duplex ultrasonographic scanning in diagnosis of extremity vascular proximity trauma [see comments]. Arch Surg. 1993;128(12):1368-1372.

3 Ginzburg E, Montalvo B, LeBlang S, Nunez D, Martin L. The use of duplex ultrasonography in penetrating neck trauma. Arch Surg. 1996;131(7):691-693.

4 Knudson MM, Lewis FR, Atkinson K, Neuhaus A. The role of duplex ultrasound arterial imaging in patients with penetrating extremity trauma. Arch Surg. 1993;128(9):1033-1037. discussion 1037–1038

5 Meissner M, Paun M, Johansen K. Duplex scanning for arterial trauma. Am J Surg. 1991;161(5):552-555.

6 Busquets AR, Acosta JA, Colon E, Alejandro KV, Rodriguez P. Helical computed tomographic angiography for the diagnosis of traumatic arterial injuries of the extremities. J Trauma. 2004;56:625-628.

7 Inaba K, Potzman J, Munera F, et al. Multi-slice CT angiography for arterial evaluation in the injured lower extremity. J Trauma. 2006;60:502-506. discussion 506–507

8 Munera F, Soto JA, Palacio DM, et al. Penetrating neck injuries: helical CT angiography for initial evaluation. Radiology. 2002;224:366-372.

9 Nunez DBJr, Torres-Leon M, Munera F. Vascular injuries of the neck and thoracic inlet: helical CT-angiographic correlation. Radiographics. 2004;24:1087-1098. discussion 1099–1100

10 Soto JA, Munera F, Cardoso N, Guarin O, Medina S. Diagnostic performance of helical CT angiography in trauma to large arteries of the extremities. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:188-196.

11 Utter GH, Hollingworth W, Hallam DK, Jarvik JG, Jurkovich GJ. Sixteen-slice CT angiography in patients with suspected blunt carotid and vertebral artery injuries. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:838-848.

12 Miller-Thomas MM, West OC, Cohen AM. Diagnosing traumatic arterial injury in the extremities with CT angiography: pearls and pitfalls. Radiographics. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S133-S142.

13 Melton SM, Kerby JD, McGiffin D, et al. The evolution of chest computed tomography for the definitive diagnosis of blunt aortic injury: a single-center experience. J Trauma. 2004;56:243-250.

14 Chen MY, Miller PR, McLaughlin CA, Kortesis BG, Kavanagh PV, Dyer RB. The trend of using computed tomography in the detection of acute thoracic aortic and branch vessel injury after blunt thoracic trauma: single-center experience over 13 years. J Trauma. 2004;56:783-785.

15 Snyder WH3rd, Thal ER, Bridges RA, Gerlock AJ, Perry MO, Fry WJ. The validity of normal arteriography in penetrating trauma. Arch Surg. 1978;113(4):424-426.

16 O’Gorman RB, Feliciano DV. Arteriography performed in the emergency center. Am J Surg. 1986;152(3):323-325.

17 O’Gorman RB, Feliciano DV, Bitondo CG, Mattox KL, Burch JM, Jordan GLJr. Emergency center arteriography in the evaluation of suspected peripheral vascular injuries. Arch Surg. 1984;119(5):568-573.

18 Pecunia RA, Raves JJ. A technique for evaluation of the injured extremity with single film exclusion arteriography. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170(5):448-450.

19 Ramanathan A, Perera DS, Sheriffdeen AH. Emergency femoral arteriography in lower limb vascular trauma. Ceylon Med J. 1995;40(3):105-106.

20 Dennis JW, Frykberg ER, Veldenz HC, Huffman S, Menawat SS. Validation of nonoperative management of occult vascular injuries and accuracy of physical examination alone in penetrating extremity trauma: 5- to 10-year follow-up. J Trauma. 1998;44(2):243-252. discussion 242–243