CHAPTER 1 THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRAUMA SYSTEMS

Modern trauma care consists of three primary components: prehospital care, acute surgical care or hospital care, and rehabilitation. Ideally, a society, through state (department, province, regional, etc.) government, should provide a trauma system that ensures all three components. The purpose of this chapter is to show how trauma systems have evolved, whether or not they work, and to define current problems.

The 19th century may well be described as the century of enlightenment for surgical care in combat. This was partly because of better statistical reporting, but also because of major contributions of patient care, including the introduction of anesthesia. During the Crimean War (1853–1856), the English reported a mortality rate of 92.7% in cases of penetrating wounds of the abdomen, and the French had a rate of 91.7%. During the American War Between the States, there were 3031 deaths among the 3717 cases of abdominal penetrating wounds and a mortality rate of 87.2%.

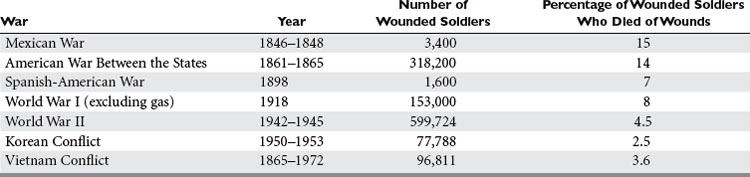

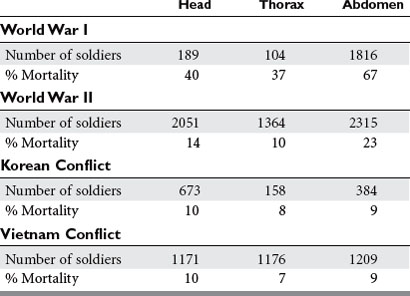

Since World War II, many contributions to combat surgical care have led to reductions in mortality and morbidity. Comparative mortality rates for various conflicts are listed in Table 1. Surgical mortality is shown in Table 2. The introduction of antibiotics and improvements in anesthesia, surgical techniques, and rapid prehospital transport are just a few of the innovations that have led to better outcomes.

MODERN TRAUMA SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT

Between the two world wars, some significant advances were made in civilian trauma care. Böhler formed the first civilian trauma system in Austria in 1925. Although initially directed at work-related injuries, it eventually expanded to include all accidents. At the onset of World War II, the Birmingham Accident Hospital was founded. It continued to provide regional trauma care until recently. By 1975, Germany had established a nationwide trauma system, so that no patient was more than 15–20 minutes from one of these regional centers. Due to the work of Tscherne and colleagues, this system has continued into the present, and mortality has decreased by over 60% (Figure 1).

In North America, foundations for modern trauma systems were being undertaken. In 1912, at a meeting of the American Surgical Association in Montreal, a committee of five was appointed to prepare a statement on the management of fractures. This led to a standing committee. One year later, the American College of Surgeons was founded, and in May 1922, the Board of Regents of the American College of Surgeons started the first Committee on Fractures with Charles Scudder, MD, as chair. This eventually became the Committee on Trauma. Another function begun by the college in 1918 was the Hospital Standardization Program, which evolved into the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals. One function of this standardization program was an embryonic start of a trauma registry with acquisition of records of patients who were treated for fractures. In 1926, the Board of Industrial Medicine and Traumatic Surgery was formed. Thus, it was the standardization program by the American College of Surgeons, the Fracture Committee appointed by the American College of Surgeons, the availability of patient records from the Hospital Standardization Program, and the new Board of Industrial Medicine in Traumatic Surgery that provided the seeds of the trauma system.

SOLUTIONS

The fundamental problem in developing regions is setting priorities. If one accepts that DALYs are a reasonable approach to developing sound health care policy, then we can examine the 10 most common causes of DALYs. A rank order of the 10 most frequent DALYs in developing countries are unipolar major depression, road traffic accidents, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cerebral vascular disease, tuberculosis, lower respiratory infections, war, diarrheal diseases, and HIV. I am biased, but I believe that road traffic accidents may be the most cost-effective DALY to try to address. Prevention would clearly play a major role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, and cerebral vascular disease, if the United States (among others) simply quit making and exporting cigarettes. I would also argue that as the world economy becomes more globalized and developing countries become economic powers in their own right, it is important for us to be involved early on in providing the infrastructure for managing health care in general and trauma care in particular.

Bazzoli GJ. Community-based trauma system development: key barriers and facilitating factors. J Trauma. 1999;47:S22-S25. (Suppl)

Bazzoli GJ, Madura KJ, Cooper GF, et al. Progress in the development of trauma systems in the United States. JAMA. 1995;273:395-401.

Cales RH, Trunkey D. Preventable trauma deaths: a review of trauma care system development. JAMA. 1985;254:1059-1063.

Cannon WB. Traumatic Shock. New York: Appleton & Company, 1923.

Comprehensive Assessment of the Florida Trauma System. University of Florida and University of South Florida. J Trauma. 2006;61:261.

Jurkovich GJ, Mock C. Systematic review of trauma system effectiveness based on registry comparisons. J Trauma. 1999;47:S46-S55. (Suppl)

Loria FL. Historical Aspects of Abdominal Injury. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1968.

MacKenzie EJ. Review of evidence regarding trauma system effectiveness resulting from panel studies. J Trauma. 1999;47:S34-S41. (Suppl)

MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al. A national evaluation of the effect on trauma center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:366-378.

Majno G. The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Murray JL, Lopez AD, editors. The Global Burden of Disease. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1996.

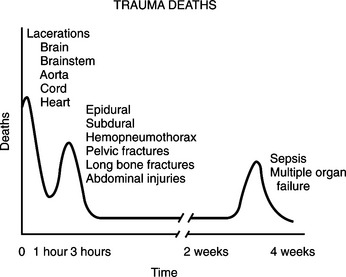

Trunkey DD. Trauma. Sci Am. 1983;249:28-35.

Wangensteen OH, Wangensteen SD. The Rise of Surgery: From Empiric Craft to Scientific Discipline. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1978.

West JG, Williams MJ, Trunkey DD, Wolferth CC. Trauma systems: current status—future challenges. JAMA. 1988;259:3597-3600.

Woodward JJ. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1875.