chapter 5

The Cerebral Hemispheres and Cerebellum

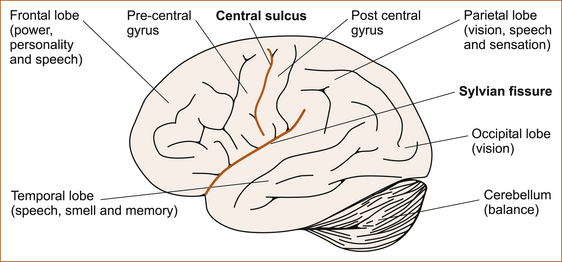

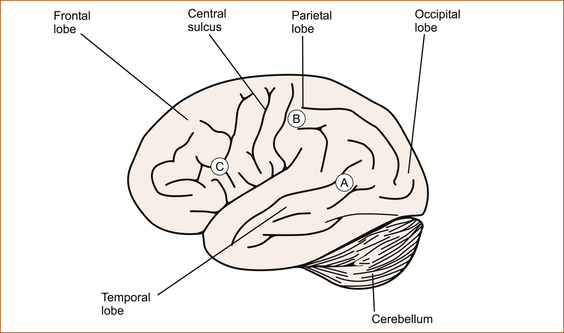

ASSESSMENT OF HIGHER COGNITIVE FUNCTION

Although subtitled ‘Assessment of higher cognitive function’, this chapter will not deal with the very complex neuropsychological testing that can be performed in patients with impairment of cognitive function. Rather, this chapter discusses a simplistic assessment of language disturbances and some very basic higher cortical functions, in particular of the parietal lobes, which can be used while taking the neurological history and examining the patient to localise the site of the pathology within the nervous system. This involves the usage of terms such as the primary pathways and secondary association areas. These terms are an aid to understanding and there is no evidence that the parietal lobes are ‘hard-wired’ in such a manner. In fact, symptoms from lesions in a part of the nervous system do not necessarily reflect the function of that part; the symptoms may arise from either a loss of certain functions or functional overactivity of the portions of the brain that remain intact [1]. The higher cortical functions represent the parallels of latitude within the cerebral hemisphere and, as already stated, ‘the pathology is ALWAYS at the level of the parallel of latitude’. More comprehensive discussions of higher cortical function can be found in the major textbooks [1–3]. Figure 5.1 gives a lateral view of the cerebral hemispheres and the cerebellum. The frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal lobes and the various functions pertaining to those lobes are shown.

THE FRONTAL LOBES

• changes in personality or behaviour

• difficulty walking in the absence of any weakness or sensory symptoms in the legs (a condition referred to as an apraxia of gait)

Contralateral weakness

The area just in front of the central sulcus, referred to as the pre-central gyrus (see Figure 5.1), is the origin of the motor fibres that innervate the muscles on the opposite side of the body. This pathway is referred to as the corticospinal tract and it crosses the midline at the level of the foramen magnum, the junction of the lower end of the brainstem and the upper end of the cervical spinal cord. Lesions affecting the pre-central gyrus will result in a contralateral hemiparesis affecting the face, arm and leg although, one limb may be weaker than the other and the face may be affected to a variable degree (partial weakness) or with hemiplegia (total weakness).

The clues that the hemiparesis is derived from a lesion in the frontal lobe are:

• conjugate eye deviation, in which the eyes look away from the side of the weakness and towards the side of the lesion due to involvement of the area of the frontal lobe that controls conjugate deviation of the eyes to the opposite side

• cortical sensory signs due to associated involvement of the parietal lobe on that side

Changes to personality or behaviour

An inability to perform acts voluntarily or to make decisions is seen in patients with pre-frontal problems and is termed abulia, reflecting pathology in the medial aspect of the frontal lobes. Abulia sometimes occurs with a subarachnoid haemorrhage (bleeding into the subarachnoid space) from vasospasm of the anterior cerebral artery related to a ruptured berry aneurysm on the anterior communicating artery (see Chapter 10, ‘Cerebrovascular disease’).

Difficulty walking

Another presentation of patients with frontal lobe pathology is apraxia of gait. The history is one of progressive difficulty walking in the absence of any weakness, sensory disturbance, ataxia or extrapyramidal dysfunction to account for the difficulty walking. It is as if the patient has forgotten how to walk. This is discussed in Chapter 12, ‘Back pain and common leg problems with or without difficulty walking’.

• a grasp reflex, where the patient involuntarily grasps an object (usually the examiner’s hand) placed in the palm of their hand

• a positive palmo-mental reflex, where the palm of the hand is stroked and there is retraction of the ipsilateral chin beneath the lips

• a pout reflex, where the patient purses the lips when a stimulus is applied to them.

THE PARIETAL LOBES

Patients with parietal lobe problems may present in a number of ways:

• speech disturbance such as fluent dysphasia and, if Wernicke’s area in the posterior temporal lobe is also affected, the patient may also present with confusion (discussed in the section ‘Disturbances of speech’ below)

• disturbances of vision in the contralateral visual field

• lost and disoriented patients who appear to be lost or disorientated even in a familiar environment

• a concerned relative brings the patient for assessment, as some patients are not even aware of any problem at all and the problem is only detected when another person observes that there is something wrong.

Speech disturbance (dysphasia) and the term RAAF (an abbreviation for the Royal Australian Air Force) best describe the features of problems in the dominant hemisphere, while the term ‘lost in space’ is the easy way to remember the characteristics of non-dominant parietal lobe problems (see Table 5.1). RAAF refers to the clinical findings seen in dominant parietal lobe problems and, in its pure form, is referred to as Gerstmann’s syndrome (for an explanation of RAAF, see ‘Gerstmann’s syndrome’ below).

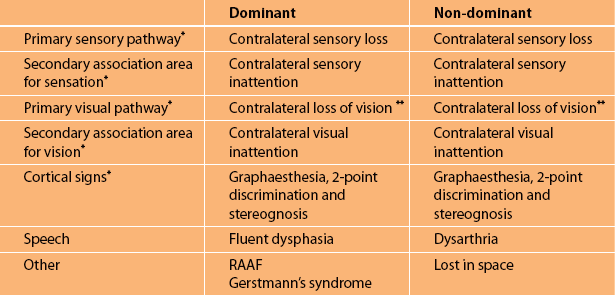

TABLE 5.1

Summary of the clinical features with lesions of the dominant and non-dominant parietal lobes

∗It can be seen that sensory and visual symptoms together with the unique parietal cortical signs are common to both the dominant and non-dominant parietal lobes. It is the speech disturbance and the parietal lobe abnormalities associated with Gerstmann’s syndrome in the dominant hemisphere and the characteristic abnormalities seen in the non-dominant hemisphere (referred to as ‘lost in space’) that differentiate between the two hemispheres.

∗∗Either loss of vision in the opposite visual field (hemianopia) or loss of vision in the upper or lower aspect of the visual field on the opposite side (quadrantanopia).

Abnormalities of vision

• Contralateral loss of vision. The optic radiation from the contralateral visual field passes through the parietal lobes to the occipital lobe (see Figure 5.1). If the ‘primary pathways’ are affected, there will be a loss of vision on the contralateral side resulting in a lower quadrantanopia if only the parietal lobe is affected, but often the optic radiation fibres in the temporal lobe are also affected and the resulting deficit is a contralateral homonymous (the visual field disturbance is identical when each eye is tested separately) hemianopia.

• Contralateral visual inattention. If the ‘primary visual pathways’ are preserved, but the so-called ‘secondary association areas’ are affected, there will be visual inattention elicited with double simultaneous stimuli. The patient is unable to appreciate the visual stimulus in one visual field, usually a moving finger applied simultaneously to both visual fields, but can if only one visual field is stimulated at a time.

Abnormalities of sensation

• Contralateral loss of sensation affecting the primary sensory modalities of vibration and proprioception, pain and temperature

• Contralateral sensory inattention where the patient cannot appreciate sensation on one side of the body when the stimulus is applied simultaneously to both sides

1. Impairment of stereognosis: the patient is unable to appreciate the shape and size of an object, for example a pen or a coin, placed in the affected hand. Proprioception must not be affected, otherwise the inability to identify the object would reflect impairment of the proprioceptive pathway and not necessarily the contralateral parietal cortex as the site of abnormality.

2. Impairment of graphaesthesia: the patient is unable to identify a number drawn on the palm of the contralateral affected hand. The drawing must be greater than 4 cm in size and initially a number is drawn on the palm of the hand while the patient watches. The patient is then instructed to close their eyes and identify another number drawn on the palm. It is easier for patients to identify numbers if their palm is facing towards them and not the examiner. If light touch is severely impaired, abnormal graphaesthesia may occur and not indicate a cortical problem.

3. Impairment of 2-point discrimination: an inability to distinguish two points from one. This can be tested on any part of the body but the distance between the two points varies greatly from 1 mm on the tip of the tongue to 20–30 mm on the dorsum of the hands and feet [1]. The most useful site to test 2-point discrimination is on the fingertips where the normal distance is 3–5 mm. It is recommended to test the opposite hand (if it is normal) to determine the distance between the two points in this particular patient as this can vary from patient to patient depending on the age of the patient.

The above sensory and visual abnormalities occur with pathology in either the dominant (usually left) or non-dominant hemisphere with the three cortical signs contralateral to the side of the pathology.

The dominant hemisphere

DISTURBANCES OF SPEECH

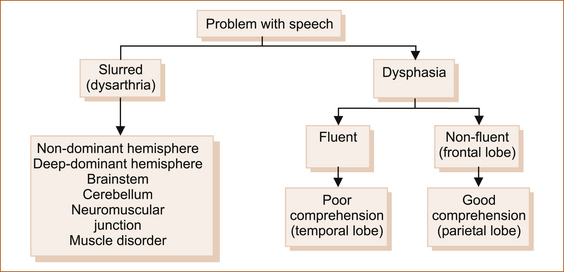

Clinicians use abnormalities of speech to localise the problem within the nervous system. On the other hand, speech therapists assess abnormalities of speech in a completely different manner and more from the therapeutic point of view. A simplified approach is shown in Figure 5.2.

• Dysarthria refers to difficulty in speaking because of impairment of the organs of speech or their innervation [4]. Dysarthria occurs with problems in many areas of the brain, including the frontal lobes or parietal lobes, cortex or deep within the subcortical white matter of either the dominant or non-dominant hemisphere. Dysarthria also occurs with brainstem and cerebellar problems, disorders of the 9th, 10th and 12th cranial nerves, disorders of the neuromuscular junction or even diseases affecting the face, tongue or palatal muscles. Although experienced neurologists may be able to differentiate between the various types of dysarthria, this is difficult for non-neurologists.

• Dysphasia is an impairment of the ability to understand and use the symbols of language, both spoken and written [4]. If the speech disturbance results in a total loss of speech, it is referred to as aphasia. Dysphasia occurs with dominant hemisphere problems (see Figure 5.3): in 90% of right-handed people and 50% of left-handed people this is the left hemisphere.

FIGURE 5.3 Lateral view of the dominant hemisphere showing the three main areas where pathological processes can produce the more commonly encountered types of dysphasia

A Temporal lobe: fluent, sensory, receptive, Wernicke’s; B Parietal lobe: fluent, amnestic, nominal; C Frontal lobe: non-fluent, motor, expressive, Broca’s Note: In this illustration the sites for speech are not strictly anatomically correct, but are simply located within the relevant lobe. Various terms have been applied to the different abnormalities of speech referred to as dysphasia.

A If the pathology is in the posterior aspect of the dominant temporal lobe (area A, Figure 5.3), the patient has word deafness where they cannot monitor their own speech or understand what is said to them and the patient will appear to be totally confused. Speech is fluent with literal (letters) and verbal (words) paraphasic errors where letters of some words or entire words are replaced by other letters or words. Non-existent words, referred to as neologisms, are invented. As patients are unable to monitor their own speech the words are often said out of sequence, described as a word salad. An example of a literal paraphasic error is where the patient says ‘mouse’ instead of ‘house’, and an example of a verbal paraphasic error is where the patient says ‘the sky is brown’. An example of a neologism is ‘rumpstle’.

B If the temporal lobe is not affected and the pathology lies within the parietal lobe (area B, Figure 5.3), the resulting speech disturbance will be less marked. As the problem is behind the central sulcus the speech will be fluent, but the patient can understand what is being said to them and they can monitor their own speech. There are occasional literal and verbal paraphasic errors, but neologisms and word salad are not a feature. These patients have a curious deficit, where they are unable to name objects, thus the term nominal dysphasia. This type of dysphasia may be a disconnection syndrome [1]. When patients are asked to name a pen or a part of a wristwatch, for example, they struggle to find the appropriate word, but they can often but not always exhibit an understanding of how the object is used.

C As the motor cortex is very closely related to the area in the frontal lobe that is involved with the production of speech (area C, Figure 5.3), a frontal lobe disorder of speech is almost invariably associated with a contralateral hemiparesis (partial weakness) or hemiplegia (total weakness). The patient can understand what is being said; they know exactly what they want to say but are unable to produce the words. However, they are not mute, which is the inability to produce sound. They give the appearance of having a stutter of variable severity reflecting the severity of the underlying speech disturbance. The patient frequently becomes very frustrated at the inability to express themselves. If the examiner shows the patient a pencil, for example, and asks them to name the object, the patient can be seen to be struggling to express the correct word. If after several attempts the examiner correctly names the object, the patient will nod in agreement.

There are a number of speech disturbances that are referred to as disconnection syndromes. These include conduction aphasia, pure word deafness and pure word blindness, to name just a few. These are believed to result from lesions affecting the association pathways joining the primary receptive areas to the language areas and not from lesions affecting the cortical language areas. A detailed discussion of these seldom encountered speech abnormalities is beyond the scope of this book, but can be found in textbooks [1–3].

The non-dominant hemisphere

This is the right hemisphere in 90% of right-handed patients and 50% of left-handed patients. The simple method for remembering the abnormalities that occur in lesions of the non-dominant parietal lobe is the phrase ‘lost in space’. This consists of neglect of one side of the body, usually the left side because the right hemisphere is the non-dominant hemisphere in most patients. The patient may present with an inability to dress themselves, referred to as dressing apraxia, often only placing one arm in the sleeve of their coat, and they may neglect to shave themselves or apply makeup on one side of the face. Strictly speaking this is not true dressing apraxia, but the patient does have difficulty dressing because they are neglecting one side. Dressing apraxia where patients cannot dress themselves is a feature of dominant parietal lobe lesions. This neglect can be so severe that the patient may not be aware that their arm and leg are weak. This is referred to as anosognosia. Rarely, some patients may not even recognise the limb as their own, a condition that is called autotopagnosia. These abnormalities are often associated with visual field disturbances, visual or sensory inattention and, if the frontal lobe is involved, hemiparesis.

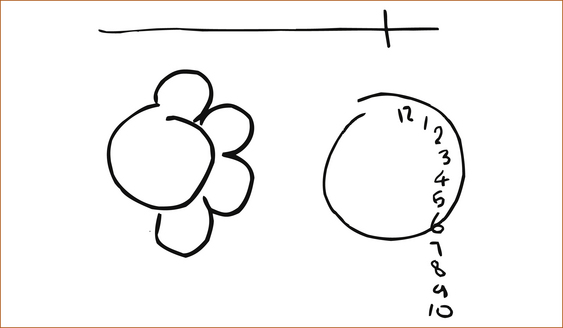

There are a variety of tests that can be employed to demonstrate this neglect or ‘lost in space’. These include bisecting a line, drawing a map of the country and placing the capital cities on the map or drawing a house, a bicycle, a daisy or a clock face. Invariably, one side of the illustration is not completed; some examples are shown in Figure 5.4.

There are a number of very rare problems referred to as apraxia that may be seen in patients with parietal lobe dysfunction. Apraxia is an impairment of the ability to use objects correctly in the absence of any obvious physical disability that would prevent them from doing so. Apraxia can be elicited by requesting the patient to demonstrate how to use a toothbrush, hammer or comb [1–3]. These are described more fully at the end of this chapter.

THE OCCIPITAL LOBES

The presenting symptoms of occipital lobe pathology include:

• Visual loss. The occipital lobes are the termination of the visual pathways and are essential for visual perception and recognition. The pathways are illustrated in Figure 4.1. The fibres from the medial half of the orbit cross in the optic chiasm, and lesions of the occipital lobe will result in a congruent contralateral visual field loss termed a homonymous hemianopia. Blindness can result from bilateral occipital lobe lesions and, in these circumstances, some patients are unaware that they are blind and behave as if they can see, a condition called Anton’s syndrome or cortical blindness. The pupillary light reflexes are preserved and the eyes and fundi are normal to examination.

• Prosopagnosia. Very occasionally patients may present with prosopagnosia, which is an inability to recognise their own features in a mirror or the faces of other people. It is almost invariably associated with a visual field abnormality, usually an upper quadrantanopia.

• Visual illusions, also termed metamorphopsias, are distortions of size, form or colour. Objects may seem too small (micopsia) or too large (macropsia).

• Visual hallucinations, both unformed and formed, arise out of the occipital lobe or the junction between the occipital and temporal lobes. Formed visual hallucinations include objects, animals or people, but these may be of distorted size, either larger or smaller than normal. Unformed visual hallucinations include flashing lights, colours, stars, circles or squares and also reflect occipital lobe pathology.

THE CEREBELLUM

Disorders of the cerebellum were first characterised in the latter part of the 19th century and in the early part of the 20th century [5, 6]. Babinski recognised the impairment of rapid alternating movements and referred to this as dys- or adiadochokinesis [6].

The classic presenting features of disorders of the cerebellum include incoordination of voluntary movement (referred to as ataxia), a characteristic intention tremor (see Chapter 13, ‘Abnormal movements and difficulty walking due to central nervous system problems’) and difficulty walking due to disequilibrium and dysarthria.

• Ataxia is tested in the upper limbs by asking the patient to touch their nose and then your finger. Ensure that your finger is far enough away from the patient so that the patient has to extend their arms fully; if it is not, the patient can anchor their arm against the chest wall and disguise any ataxia. In the lower limbs ataxia is tested by asking the recumbent patient to lift their leg high up in the air and touch the examiner’s finger and then place their heel on their own kneecap. One looks for unsteadiness as the patient’s finger approaches the examiner’s finger or their nose and as the heel approaches the finger or kneecap.

• Ataxia is often examined by watching the patient slide their heel down the shin. This, however, can disguise ataxia because the patient can stabilise their leg with the heel running along the shin. Abnormalities of cerebellar function will lead to the test being performed slowly and inaccurately.

• Cerebellar function is also tested by performing rapid alternating movements. For the upper limbs this is tested by asking the patient to tap the back and then the palm of their hand on the back of their other hand. For the lower limbs the patient taps their heel up and down on the floor.

• Patients with cerebellar disorders may also develop involuntary jerking of the eyes referred to as nystagmus. This is elicited by asking the patient to look up, down and to each side.

• The dysarthria that occurs with cerebellar dysfunction is characterised by slow slurring of the speech, or speech where the words are broken up into syllables, referred to as scanning dysarthria. This latter form of dysarthria is characteristic of cerebellar pathology. Another term that is very descriptive is explosive speech because the words are at times very soft and at other times very loud.

• Difficulty walking related to cerebellar dysfunction is discussed in Chapter 12, ‘Back pain and common leg problems with or without difficulty walking’. In essence, lesions of the anterior of vermis of the cerebellum result in truncal ataxia while lesions affecting the cerebellar hemispheres cause ataxia of the limbs.

THE TEMPORAL LOBES

The disorder of speech has been discussed earlier in this chapter. The visual field defect is a contralateral homonymous upper quadrantanopia. The various hallucinations are discussed in Chapter 8, ‘Seizures and epilepsy’. Although the temporal lobes are involved with vestibular function, vertigo is only rarely seen with temporal lobe pathology; it may be the aura of a seizure (see Chapter 8).

Disturbances of memory

Memory includes three basic mental processes:

1. registration (the ability to perceive, recognise, and establish information in the central nervous system)

2. retention (the ability to retain registered information)

3. recall (the ability to retrieve stored information at will).

TRANSIENT GLOBAL AMNESIA

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is one of the more commonly encountered disturbances of memory.

The diagnostic criteria include the episode being witnessed and involve anterograde amnesia. The patient must not have any evidence of neurological signs or deficits, features of epilepsy, active epilepsy or recent head injury. Finally the episode must have resolved within 24 hours [7]. These patients appear bewildered; they keep asking the same questions over and over again because they are unable to lay down new memory. Patients remain alert and attentive, and cognition is not impaired. However, they are disoriented in time and place. In all other respects they are normal. The duration of attacks is usually 1–8 hours but should be less than 24 hours. After the attack resolves, the period of amnesia shrinks with a permanent memory loss of variable duration from just a short period at the commencement of the episode to the entire episode.

The aetiology of this condition is unknown, but punctate lesions in the lateral aspect of the hippocampal formation on either side or bilaterally have been demonstrated by diffusion weighted MRI (dwMRI), not in the hyperacute phase but at 48 hours [8].

DEMENTIA

A detailed discussion of dementia is beyond the scope of this chapter. A more detailed discussion can be found in Chapter 14, ‘Miscellaneous neurological disorders’.

TESTING HIGHER COGNITIVE FUNCTION

Higher cognitive function (HCF) consists of memory, orientation, concentration, language, stimulus recognition (examined by tests for agnosia), and performance of learned skilled movements (examined by tests for apraxia). Agnosia is the inability to recognise sensory stimuli and apraxia is the inability to use objects properly [4].

The Mini-Mental State Examination

The Mini-Mental State Examination [9] is a standardised, widely accepted test that is used to screen for cognitive impairment. It examines orientation in some detail and then briefly touches on registration and recall, attention/concentration, language and constructional abilities. It consists of 11 questions and can be administered in 5–10 minutes. This is a screening test that may indicate a need for more extensive testing. Details are given in Appendix A.

SOME RARER ABNORMALITIES OF HIGHER COGNITIVE FUNCTION

• Auditory agnosia – the inability to recognise the significance of sounds (dominant temporal lobe)

• Finger agnosia – the loss of ability to indicate one’s own or another’s fingers (dominant parietal lobe)

• Tactile agnosia – the inability to recognise familiar objects by touch or feel (parietotemporal cortices, possibly including the 2nd somatosensory cortex)

• Visual agnosia – the inability to recognise objects by sight (posterior occipital and/or temporal lobe(s) in the brain)

• Prosopagnosia – the inability to recognise faces of people well known or newly introduced to the patient (mesial cortex of occipital and temporal lobes)

• Anosognosia – the inability to recognise that a part of the body is affected by disease (non-dominant parietal lobe)

Apraxia

Apraxia is defined as a disorder of skilled movement not caused by weakness, akinesia, deafferentation, abnormal tone or posture, movement disorders such as tremors or chorea, intellectual deterioration, poor comprehension or uncooperativeness [10]. It is one of the best localising signs of the mental status examination and also predicts disability. Thus, for an experienced neurologist detection of the various forms of apraxia is very important. The more common forms of apraxia are listed below together with the most common site of the pathology.

• Sensory (ideational) apraxia – loss of the ability to make proper use of an object due to the lack of perception of its purpose (dominant posterior temporoparietal junction)

• Constructional apraxia – the individual fails to represent spatial relations correctly in drawing or construction (non-dominant parietal lobe)

• Ideomotor apraxia – simple single acts can be performed but not a sequence of acts (dominant parietal lobe and the premotor cortex)

• Dressing apraxia – difficulty in orienting articles of clothing with reference to the body; the obvious test is to ask the patient to put on an article of clothing (non-dominant parietal lobe if one side is neglected but dominant if absolutely no idea how to dress)

Wernicke–Korsakoff encephalopathy

The term Wernicke encephalopathy [11, 12] is used to describe the clinical triad of confusion, ataxia and nystagmus (or ophthalmoplegia). At autopsy, punctate hemorrhages affecting the gray matter around the 3rd and 4th ventricles and aqueduct of Sylvius are seen. When persistent learning and memory deficits are present, the symptom complex is often called Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome. Korsakoff syndrome or amnestic disorder is characterised by the inability to learn new information, while other higher cognitive functions are retained. Lack of motivation, lack of insight, a flat affect and denial of difficulties are common. Spontaneous speech is minimal. Confabulation (false memories which the patient believes to be true) may occur in the early stages but usually disappears with time. These patients are severely disabled and are usually incapable of independent living. The syndrome is due to thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency related to malnutrition and is very common in patients suffering from alcoholism.

REFERENCES

1. Adams, R.D., Victor, M. Principles of neurology. New York: McGraw–Hill Book Company; 1985. [1186].

2. Rowland, L.P., eds. Merritt’s textbook of neurology, Vol 11e. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

3. Wilson J.D., et al, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, 12th edn, New York: McGraw–Hill, 1991.

4. Dorland’s pocket medical dictionary, 21st edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1968.

5. Holmes, G. The cerebellum of man: Hughlings Jackson lecture. Brain. 1939;62:1.

6. Babinski, J. De l’asynergie cerebelleuse. Rev Neurol. 1899;7:806.

7. Hodges, J.R., Warlow, C.P. Syndromes of transient amnesia: Towards a classification. A study of 153 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(10):834–843.

8. Sedlaczek, O., et al. Detection of delayed focal MR changes in the lateral hippocampus in transient global amnesia. Neurology. 2004;62(12):2165–2170.

9. Folstein, M.F., Folstein, S.E., McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.

10. Heilman, K.M., Rothi, L.J.G. Apraxia. In: Heilman KM, Valenstein E (eds). Clinical neuropsychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993:141–163.

11. Thomson, A.D., et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy revisited. [translation of the case history section of the original manuscript by Carl Wernicke ‘Lehrbuch der Gehirnkrankheiten fur Aerzte and Studirende’ (1881) with a commentary]. Alcohol. 2008;43(2):174–179.

12. Pearce, J.M. Wernicke–Korsakoff encephalopathy. Eur Neurol. 2008;59(1–2):101–104.