Chapter 10 The Cardiovascular Exam

A. Generalities

1 What are the main components of the cardiovascular physical examination?

The general appearance of the patient (inspection)

The general appearance of the patient (inspection)

The arterial pulse (palpation); this component also should include assessment of the arterial blood pressure (discussed separately in Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 37–127)

The arterial pulse (palpation); this component also should include assessment of the arterial blood pressure (discussed separately in Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 37–127)

The central venous pressure and the jugular venous pulse (inspection)

The central venous pressure and the jugular venous pulse (inspection)

Precordial impulses and silhouette (inspection, palpation, and percussion of the point of maximal impulse [PMI])

Precordial impulses and silhouette (inspection, palpation, and percussion of the point of maximal impulse [PMI])

B. General (Physical) Appearance

2 What aspects of general appearance should be observed in evaluating cardiac patients?

As suggested by Perloff, one should sequentially evaluate the following nine areas:

See Tables 10-1 and 10-2.

Table 10-1 Diagnostic Clues: Body and Facies, Gestures and Gait, Face and Ears

| Body Appearance and Facies |

The anasarca of congestive heart failure The anasarca of congestive heart failure |

The struggling, anguished, frightened, orthopneic, and diaphoretic look of pulmonary edema The struggling, anguished, frightened, orthopneic, and diaphoretic look of pulmonary edema |

The tall stature, long extremities (with arm span exceeding patient’s height), and sparse subcutaneous fat of Marfan’s syndrome (mitral valve prolapse, aortic dilation, and dissection) The tall stature, long extremities (with arm span exceeding patient’s height), and sparse subcutaneous fat of Marfan’s syndrome (mitral valve prolapse, aortic dilation, and dissection) |

The long extremities, kyphoscoliosis, and pectus carinatum of homocystinuria (arterial thrombosis) The long extremities, kyphoscoliosis, and pectus carinatum of homocystinuria (arterial thrombosis) |

The tall stature and long extremities of Klinefelter’s syndrome (atrial or ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and even tetralogy of Fallot) The tall stature and long extremities of Klinefelter’s syndrome (atrial or ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and even tetralogy of Fallot) |

The tall stature and thick extremities of acromegaly (hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and conduction defects) The tall stature and thick extremities of acromegaly (hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and conduction defects) |

The short stature, webbed neck, low hairline, small chin, wide-set nipples, and sexual infantilism of Turner’s syndrome (coarctation of the aorta and valvular pulmonic stenosis) The short stature, webbed neck, low hairline, small chin, wide-set nipples, and sexual infantilism of Turner’s syndrome (coarctation of the aorta and valvular pulmonic stenosis) |

The dwarfism and polydactyly of Ellis-van Creveld syndrome (atrial septal defects and common atrium) The dwarfism and polydactyly of Ellis-van Creveld syndrome (atrial septal defects and common atrium) |

The morbid obesity and somnolence of obstructive sleep apnea (hypoventilation, pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale) The morbid obesity and somnolence of obstructive sleep apnea (hypoventilation, pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale) |

The truncal obesity, thin extremities, moon face, and buffalo hump of hypertensive patients with Cushing’s syndrome The truncal obesity, thin extremities, moon face, and buffalo hump of hypertensive patients with Cushing’s syndrome |

The mesomorphic, overweight, balding, hairy, and tense middle-aged patient with coronary artery disease The mesomorphic, overweight, balding, hairy, and tense middle-aged patient with coronary artery disease |

The hammer toes and pes cavus of Friedreich’s ataxia (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, angina, and sick sinus syndrome) The hammer toes and pes cavus of Friedreich’s ataxia (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, angina, and sick sinus syndrome) |

The straight lower back of ankylosing spondylitis (aortic regurgitation and complete heart block) The straight lower back of ankylosing spondylitis (aortic regurgitation and complete heart block) |

| Gestures, Gait, and Stance |

The Levine’s sign (clenched fist over the chest of patients with an acute myocardial infarction) The Levine’s sign (clenched fist over the chest of patients with an acute myocardial infarction) |

The preferential squatting of tetralogy of Fallot The preferential squatting of tetralogy of Fallot |

The ataxic gait of tertiary syphilis (associated with aortic aneurysm and regurgitation) The ataxic gait of tertiary syphilis (associated with aortic aneurysm and regurgitation) |

The waddling gait, lumbar lordosis, and calves pseudohypertrophy of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a pseudo infarction pattern on ECG) The waddling gait, lumbar lordosis, and calves pseudohypertrophy of Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a pseudo infarction pattern on ECG) |

| Face and Ears |

Pulsatility of the earlobes (tricuspid regurgitation) Pulsatility of the earlobes (tricuspid regurgitation) |

Head bobbing (De Musset’s and Lincoln’s signs) Head bobbing (De Musset’s and Lincoln’s signs) |

The round and chubby face of congenital pulmonary stenosis The round and chubby face of congenital pulmonary stenosis |

The hypertelorism, pigmented moles, webbed neck, and low-set ears of Turner’s syndrome The hypertelorism, pigmented moles, webbed neck, and low-set ears of Turner’s syndrome |

The round and chubby face of congenital valvular pulmonic stenosis The round and chubby face of congenital valvular pulmonic stenosis |

The elfin face (small chin, malformed teeth, wide-set eyes, patulous lips, baggy cheeks, blunt and upturned nose) of congenital stenosis of the pulmonary arteries and supravalvular aortic stenosis—often associated with hypercalcemia and mental retardation. The elfin face (small chin, malformed teeth, wide-set eyes, patulous lips, baggy cheeks, blunt and upturned nose) of congenital stenosis of the pulmonary arteries and supravalvular aortic stenosis—often associated with hypercalcemia and mental retardation. |

The unilateral lower facial weakness of infants with cardiofacial syndrome—this can be encountered in 5–10% of infants with congenital heart disease (usually ventricular septal defect); often noticeable only during crying. The unilateral lower facial weakness of infants with cardiofacial syndrome—this can be encountered in 5–10% of infants with congenital heart disease (usually ventricular septal defect); often noticeable only during crying. |

The premature aging of Werner’s syndrome and progeria (associated with premature coronary artery and systemic atherosclerotic disease) The premature aging of Werner’s syndrome and progeria (associated with premature coronary artery and systemic atherosclerotic disease) |

The drooping eyelids, expressionless face, receding hairline, and bilateral cataracts of Steinert’s disease (myotonic dystrophy, associated with conduction disorders, mitral valve prolapse) The drooping eyelids, expressionless face, receding hairline, and bilateral cataracts of Steinert’s disease (myotonic dystrophy, associated with conduction disorders, mitral valve prolapse) |

The epicanthic fold, protruding tongue, small ears, short nose, and flat bridge of Down syndrome (endocardial cushion defects) The epicanthic fold, protruding tongue, small ears, short nose, and flat bridge of Down syndrome (endocardial cushion defects) |

The dry and brittle hair, loss of lateral eyebrows, puffy eyelids, apathetic face, protruding tongue, thick and sallow skin of myxedema (associated with pericardial and coronary artery disease) The dry and brittle hair, loss of lateral eyebrows, puffy eyelids, apathetic face, protruding tongue, thick and sallow skin of myxedema (associated with pericardial and coronary artery disease) |

The macroglossia not only of Down syndrome and myxedema, but also of amyloidosis (linked to restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure) The macroglossia not only of Down syndrome and myxedema, but also of amyloidosis (linked to restrictive cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure) |

The paroxysmal facial and neck flushing of carcinoid syndrome (with pulmonic stenosis and tricuspid stenosis/regurgitation) The paroxysmal facial and neck flushing of carcinoid syndrome (with pulmonic stenosis and tricuspid stenosis/regurgitation) |

The saddle-shaped nose of polychondritis (associated with aortic aneurysm) The saddle-shaped nose of polychondritis (associated with aortic aneurysm) |

The tightening of skin and mouth, scattered telangiectasias, and hyperpigmentation/hypopigmentation of scleroderma (with pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, and myocarditis) The tightening of skin and mouth, scattered telangiectasias, and hyperpigmentation/hypopigmentation of scleroderma (with pulmonary hypertension, pericarditis, and myocarditis) |

The flushed cheeks and cyanotic lips of mitral stenosis (acrocyanosis) The flushed cheeks and cyanotic lips of mitral stenosis (acrocyanosis) |

The gargoylism of Hurler’s syndrome (associated with mitral and/or aortic disease) The gargoylism of Hurler’s syndrome (associated with mitral and/or aortic disease) |

The short palpebral fissures, small upper lip, and hypoplastic mandible of fetal alcohol syndrome (associated with atrial or ventricular septal defects) The short palpebral fissures, small upper lip, and hypoplastic mandible of fetal alcohol syndrome (associated with atrial or ventricular septal defects) |

The diagonal earlobe crease as a (questionable) marker of coronary artery disease (earlobe sign [also known as Frank’s sign]) The diagonal earlobe crease as a (questionable) marker of coronary artery disease (earlobe sign [also known as Frank’s sign]) |

Table 10-2 Diagnostic Clues: Eyes, Extremities, Skin, Thorax, and Abdomen

| Eyes |

Xanthelasmhas of dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease (CAD) Xanthelasmhas of dyslipidemia and coronary artery disease (CAD) |

The enlarged lacrimal glands of sarcoidosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy, conduction defects, and, possibly, cor pulmonale) The enlarged lacrimal glands of sarcoidosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy, conduction defects, and, possibly, cor pulmonale) |

The cataracts and deafness of “rubella syndrome” (patent ductus arteriosus [PDA] or stenosis of the pulmonary artery) The cataracts and deafness of “rubella syndrome” (patent ductus arteriosus [PDA] or stenosis of the pulmonary artery) |

The stare and proptosis of increased central venous pressure The stare and proptosis of increased central venous pressure The lid lag, stare, and exophthalmos of hyperthyroidism (tachyarrhythmias, angina, and high output failure) The lid lag, stare, and exophthalmos of hyperthyroidism (tachyarrhythmias, angina, and high output failure) |

The conjunctival petechiae of endocarditis The conjunctival petechiae of endocarditis |

The conjunctivitis of Reiter’s disease (pericarditis, aortic regurgitation, and prolongation of the P-R interval) The conjunctivitis of Reiter’s disease (pericarditis, aortic regurgitation, and prolongation of the P-R interval) |

The blue sclerae of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) The blue sclerae of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) |

The icteric sclerae of cirrhosis The icteric sclerae of cirrhosis |

The Brushfield’s spots (small white spots on the periphery of the iris, usually crescentic and with an outward concavity, frequently but not exclusively seen in Down syndrome—endocardial cushion defects) The Brushfield’s spots (small white spots on the periphery of the iris, usually crescentic and with an outward concavity, frequently but not exclusively seen in Down syndrome—endocardial cushion defects) |

The fissuring of the iris (coloboma) of total anomalous pulmonary venous return The fissuring of the iris (coloboma) of total anomalous pulmonary venous return |

The dislocated lens of Marfan’s syndrome The dislocated lens of Marfan’s syndrome |

The retinal changes of hypertension and diabetes (CAD and congestive heart failure) The retinal changes of hypertension and diabetes (CAD and congestive heart failure) |

The Roth spots of bacterial endocarditis The Roth spots of bacterial endocarditis |

| Extremities |

The cyanosis and clubbing of “central mixing” (right-to-left shunts, pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas, and drainage of the inferior vena cava into left atrium) The cyanosis and clubbing of “central mixing” (right-to-left shunts, pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas, and drainage of the inferior vena cava into left atrium) |

The differential cyanosis and clubbing of PDA with pulmonary hypertension (the reversed shunt limits cyanosis and clubbing to the feet, but spares hands) The differential cyanosis and clubbing of PDA with pulmonary hypertension (the reversed shunt limits cyanosis and clubbing to the feet, but spares hands) |

The “reversed” differential cyanosis and clubbing of transposition (aorta originating from the right ventricle): hands are cyanotic and clubbed, but feet are normal The “reversed” differential cyanosis and clubbing of transposition (aorta originating from the right ventricle): hands are cyanotic and clubbed, but feet are normal |

The sudden pallor, pain, and coldness of peripheral embolization The sudden pallor, pain, and coldness of peripheral embolization |

Osler’s nodes (swollen, tender, raised, pea-sized lesion of finger pads, palms, and soles) and Janeway lesions (small, nontender, erythematous or hemorrhagic lesions of the palms or soles) of bacterial endocarditis Osler’s nodes (swollen, tender, raised, pea-sized lesion of finger pads, palms, and soles) and Janeway lesions (small, nontender, erythematous or hemorrhagic lesions of the palms or soles) of bacterial endocarditis |

The clubbing, splinter hemorrhages of endocarditis The clubbing, splinter hemorrhages of endocarditis |

The Raynaud’s of scleroderma The Raynaud’s of scleroderma |

The simian line of Down’s syndrome (atrial septal defect [ASD]) The simian line of Down’s syndrome (atrial septal defect [ASD]) |

The hyperextensible joints of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) The hyperextensible joints of osteogenesis imperfecta (aortic regurgitation) |

The nicotine finger stains of chain smokers (CAD) The nicotine finger stains of chain smokers (CAD) |

The leg edema of congestive heart failure The leg edema of congestive heart failure |

The tightly tapered and contracted fingers of scleroderma, with ischemic ulcers and hypoplastic nails (often associated with pulmonary hypertension and myocardial disease, pericarditis, and valvulopathy) The tightly tapered and contracted fingers of scleroderma, with ischemic ulcers and hypoplastic nails (often associated with pulmonary hypertension and myocardial disease, pericarditis, and valvulopathy) |

The arachnodactyly, hyperextensible joints (especially knees, wrists, and fingers), and flat feet of Marfan’s syndrome (associated with aortic disease and regurgitation) The arachnodactyly, hyperextensible joints (especially knees, wrists, and fingers), and flat feet of Marfan’s syndrome (associated with aortic disease and regurgitation) |

The ulnar deviation of rheumatoid arthritis (pericardial, valvular, or myocardial disease) The ulnar deviation of rheumatoid arthritis (pericardial, valvular, or myocardial disease) |

The mainline track lines of addicts (tricuspid regurgitation, septic emboli, and endocarditis) The mainline track lines of addicts (tricuspid regurgitation, septic emboli, and endocarditis) |

The liver palms (thenar and hypothenar erythema) of chronic hepatic congestion The liver palms (thenar and hypothenar erythema) of chronic hepatic congestion |

| Skin |

The jaundice or hepatic congestion The jaundice or hepatic congestion |

The cyanosis of right-to-left shunt The cyanosis of right-to-left shunt |

The pallor of anemia and high output failure The pallor of anemia and high output failure |

The bronzing of hemochromatosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy) The bronzing of hemochromatosis (restrictive cardiomyopathy) |

The telangiectasias of Rendu-Osler-Weber (at times associated with pulmonary arteriovenous fistulae) The telangiectasias of Rendu-Osler-Weber (at times associated with pulmonary arteriovenous fistulae) |

The neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and axillary freckles (Crowe’s sign) of von Recklinghausen’s (pheochromocytomas) The neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, and axillary freckles (Crowe’s sign) of von Recklinghausen’s (pheochromocytomas) |

The symmetric vitiligo (especially of the distal extremities) of hyperthyroidism The symmetric vitiligo (especially of the distal extremities) of hyperthyroidism |

The butterfly rash of SLE (endo-myo- pericarditis) The butterfly rash of SLE (endo-myo- pericarditis) |

The eyelid purplish discoloration of dermatomyositis (cardiomyopathy, heart block, and pericarditis) The eyelid purplish discoloration of dermatomyositis (cardiomyopathy, heart block, and pericarditis) |

The skin nodules and macules of sarcoidosis (cardiomyopathy and blocks) The skin nodules and macules of sarcoidosis (cardiomyopathy and blocks) |

The xanthomas of dyslipidemia The xanthomas of dyslipidemia |

The hyperextensible skin (and joints) of Ehlers-Danlos (mitral valve prolapse) The hyperextensible skin (and joints) of Ehlers-Danlos (mitral valve prolapse) |

The coarse and sallow skin of hypothyroidism The coarse and sallow skin of hypothyroidism |

The skin nodules (sebaceous adenomas), shagreen patches, and periungual fibromas of tuberous sclerosis (rhabdomyomas of the heart and arrhythmias) The skin nodules (sebaceous adenomas), shagreen patches, and periungual fibromas of tuberous sclerosis (rhabdomyomas of the heart and arrhythmias) |

| Thorax and Abdomen |

The thoracic bulges of ventricular septal defect/ASD The thoracic bulges of ventricular septal defect/ASD |

The pectus carinatum, pectus excavatum, and kyphoscoliosis of Marfan’s syndrome The pectus carinatum, pectus excavatum, and kyphoscoliosis of Marfan’s syndrome |

The akyphotic and straight back of mitral valve prolapse The akyphotic and straight back of mitral valve prolapse |

The systolic (and rarely diastolic) murmurs of pectus carinatum, excavatum, straight back The systolic (and rarely diastolic) murmurs of pectus carinatum, excavatum, straight back |

The barrel chest of emphysema (cor pulmonale) The barrel chest of emphysema (cor pulmonale) |

The shield chest of Turner’s syndrome The shield chest of Turner’s syndrome |

The cor pulmonale of severe kyphoscoliosis The cor pulmonale of severe kyphoscoliosis |

The ascites of right-sided or biventricular failure The ascites of right-sided or biventricular failure |

The hepatic pulsation of tricuspid regurgitation The hepatic pulsation of tricuspid regurgitation |

The positive abdominojugular reflux of congestive heart failure The positive abdominojugular reflux of congestive heart failure |

C. The Arterial Pulse

3 Which arteries should be examined during the evaluation of the arterial pulse?

Arteries on both sides should be compared to detect asymmetries suggestive of embolic, thrombotic, atherosclerotic, dissecting, or extrinsic occlusion.

Arteries on both sides should be compared to detect asymmetries suggestive of embolic, thrombotic, atherosclerotic, dissecting, or extrinsic occlusion.

Arteries of upper and lower extremities should be simultaneously examined in hypertensive patients to identify reduction in volume (or pulse delays) suggestive of aortic coarctation.

Arteries of upper and lower extremities should be simultaneously examined in hypertensive patients to identify reduction in volume (or pulse delays) suggestive of aortic coarctation.

If trying to evaluate the characteristics of the arterial waveform, you should examine only central arteries—carotid, brachial, or femoral.

If trying to evaluate the characteristics of the arterial waveform, you should examine only central arteries—carotid, brachial, or femoral.

Since this section focuses on the bedside examination of the arterial wave as part of the cardiovascular exam, we will exclusively discuss evaluation of central arteries. Assessment of peripheral vessels is discussed in Chapter 22, Extremities and Peripheral Vascular Exam, questions 1–25.

5 What alterations occur in peripheral arteries?

The major ones are an increase in amplitude and upstroke velocity. As the distance from the aortic valve increases, the primary percussion wave that is transmitted downward along the aorta begins to merge with the secondary waves that reverberate back from more peripheral arteries. This fusion leads to greater amplitude and upstroke velocity in peripheral as compared to central arteries (Fig. 10-1). This phenomenon is similar to that occurring at the shoreline, where waves tend to be taller. It is also the mechanism behind Hill’s sign, the higher indirect systolic pressure of lower extremities as compared to upper extremities (see Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 110–115).

12 What are the characteristics of a normal arterial pulse?

A normal arterial pulse comprises a primary (systolic) and a secondary (diastolic) wave. These are separated by a dicrotic notch (dikrotos, double-beating in Greek), which corresponds to the closure of the semilunar valves (S2) (see Fig. 10-2).

14 How are primary and secondary waves generated?

The primary wave derives from the ejection of blood into the aorta. Its early portion (percussion wave) reflects discharge into the central aorta, whereas its mid-to-late portion (tidal wave) reflects movement of blood from the central to the peripheral aorta. The two portions are separated by an anacrotic notch, only visible on tracing and usually not palpable.

The primary wave derives from the ejection of blood into the aorta. Its early portion (percussion wave) reflects discharge into the central aorta, whereas its mid-to-late portion (tidal wave) reflects movement of blood from the central to the peripheral aorta. The two portions are separated by an anacrotic notch, only visible on tracing and usually not palpable.

The secondary wave is generated instead by the elastic back-reflection of the waveform, from the peripheral arteries of the lower half of the body.

The secondary wave is generated instead by the elastic back-reflection of the waveform, from the peripheral arteries of the lower half of the body.

18 How can you differentiate supravalvular from valvular aortic stenosis?

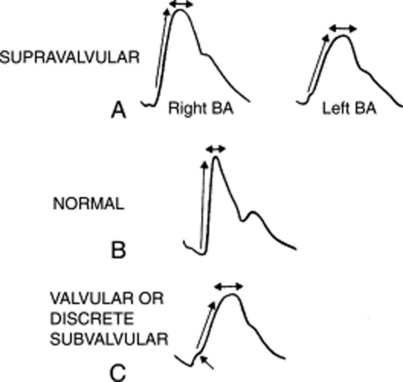

Supravalvular AS is associated with right-to-left asymmetry of the arterial pulse: the right brachial is normal while the left resembles the pulse of valvular AS (see Fig. 10-3). This is akin to aortic coarctation and underscores the importance of examining both pulses.

20 What is the significance of a brisk arterial upstroke?

The simultaneous emptying of the left ventricle into a high-pressure bed (the aorta) and a lower pressure bed. The latter can be the right ventricle (in patients with ventricular septal defect, VSD) or the left atrium (in patients with mitral regurgitation, MR). Both will allow a rapid left ventricular emptying, which, in turn, generates a brisk arterial upstroke. The pulse pressure, however, remains normal.

The simultaneous emptying of the left ventricle into a high-pressure bed (the aorta) and a lower pressure bed. The latter can be the right ventricle (in patients with ventricular septal defect, VSD) or the left atrium (in patients with mitral regurgitation, MR). Both will allow a rapid left ventricular emptying, which, in turn, generates a brisk arterial upstroke. The pulse pressure, however, remains normal.

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Despite its association with left ventricular obstruction, this disease is characterized by a brisk and bifid pulse, due to the hypertrophic ventricle and its delayed obstruction.

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Despite its association with left ventricular obstruction, this disease is characterized by a brisk and bifid pulse, due to the hypertrophic ventricle and its delayed obstruction.

22 What is pulsus paradoxus?

It is an exaggerated fall in systolic blood pressure during quiet inspiration. In contrast to evaluation of arterial contour and amplitude, pulsus paradoxus is best detected in a peripheral vessel, such as the radial. Although palpable at times, optimal detection of the pulsus paradoxus usually requires a sphygmomanometer (see Chapter 2, Vital Signs, questions 85–103).

30 What is a double-peaked pulse?

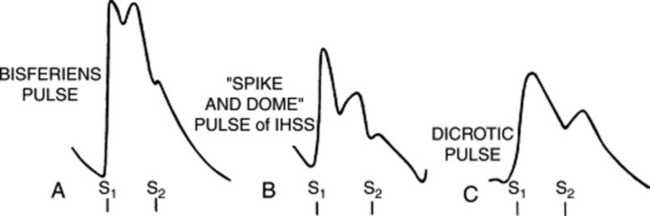

It is a pulse characterized by two palpable spikes per cycle (Fig. 10-4). The first peak always occurs in systole, whereas the second may instead occur during either systole (as part of the primary wave: pulsus bisferiens and bifid pulse) or diastole (as part of the secondary wave: dicrotic pulse).

33 What is the diagnostic significance of a pulsus bisferiens?

Double Korotkoff sound: This is heard during measurement of systolic blood pressure, with the cuff being slowly deflated. It coincides with the systolic arterial peak.

Double Korotkoff sound: This is heard during measurement of systolic blood pressure, with the cuff being slowly deflated. It coincides with the systolic arterial peak.

Traube’s femoral sound(s): Reported by Traube in 1867, this is a loud, explosive, and shot-like systolic sound heard over a large central artery (femoral usually, but also brachial or carotid) in synchrony with the arterial pulse. It is detected whenever light pressure is applied with the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the artery, coupled with mild arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head. Although more often single (and thus called pistol shot sound), it can also be double (hence, referred to as Traube’s femoral double sounds) and sometimes even triple. It reflects the sudden systolic distention of the arterial wall—like a sail filling with wind. A single shot occurs in approximately one half of all AR patients, but may also take place in other high output states. Double sounds occur in one fourth of AR patients. Lack of arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head sharply decreases the test’s sensitivity, confining it to cases with severe left ventricular dilation. Like the water hammer pulse, Traube’s sound(s) has 37–55% sensitivity for AR and 63–98% specificity.

Traube’s femoral sound(s): Reported by Traube in 1867, this is a loud, explosive, and shot-like systolic sound heard over a large central artery (femoral usually, but also brachial or carotid) in synchrony with the arterial pulse. It is detected whenever light pressure is applied with the stethoscope’s diaphragm over the artery, coupled with mild arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head. Although more often single (and thus called pistol shot sound), it can also be double (hence, referred to as Traube’s femoral double sounds) and sometimes even triple. It reflects the sudden systolic distention of the arterial wall—like a sail filling with wind. A single shot occurs in approximately one half of all AR patients, but may also take place in other high output states. Double sounds occur in one fourth of AR patients. Lack of arterial compression distal to the stethoscope’s head sharply decreases the test’s sensitivity, confining it to cases with severe left ventricular dilation. Like the water hammer pulse, Traube’s sound(s) has 37–55% sensitivity for AR and 63–98% specificity.

38 What is the prognostic value of a pulsus bisferiens?

It indicates a very large stroke volume. Hence, it may disappear with left ventricular dysfunction.

43 What is a hypokinetic pulse?

47 What is the carotid shudder?

It is a palpable thrill felt at the peak of the carotid pulse in patients with AS, AR, or both. It represents the transmission of the murmur to the artery and is a relatively specific but rather insensitive sign of aortic valvular disease (Fig. 10-5).

51 What is Corrigan’s pulse?

It is one of the various names for the bounding and quickly collapsing pulse of aortic regurgitation. This is both visible and palpable. Another common term for it is “water hammer,” but also cannonball, collapsing, or pistol-shot pulse. Corrigan’s may be so brisk as to cause other typical findings, such as De Musset’s or Lincoln’s signs (see Chapter 1, questions 53 and 54).

55 What is a pulsus durus?

A pulse so hardened that it is difficult to compress (durus, hard in Latin). This is usually a finding of arteriosclerosis, which may be associated with Osler’s sign (see Chapter 2, questions 70–72).

58 What other findings can mimic a carotid bruit?

Systolic heart murmurs: These are only transmitted to the neck. Hence, in contrast to a bruit, they are louder over the precordium than the neck.

Systolic heart murmurs: These are only transmitted to the neck. Hence, in contrast to a bruit, they are louder over the precordium than the neck.

Venous hums: These are innocent murmurs caused by flow in the internal jugular vein. In contrast to carotid bruits, they are loudest in diastole (although, actually, continuous) and can only be heard in a sitting position (see questions 120–123).

Venous hums: These are innocent murmurs caused by flow in the internal jugular vein. In contrast to carotid bruits, they are loudest in diastole (although, actually, continuous) and can only be heard in a sitting position (see questions 120–123).

59 What is the interobserver agreement on carotid bruits?

Quite good for detecting bruits, but only fair for evaluating their intensity, pitch, or duration.

60 Can carotid bruits occur in children?

Yes. In fact, they are present in 20% of children younger than 15 years of age.

D. Central Venous Pressure and Jugular Venous Pulse (Waveform)

68 Which veins should be evaluated for assessing venous pulse and CVP?

Central veins, as much in direct communication with the right atrium as possible. The ideal one is therefore the internal jugular. Of course, as part of a comprehensive examination, all visible veins should be evaluated. Since this chapter focuses on the cardiovascular exam, we will limit our discussion to jugular waveform and central venous pressure. Evaluation of peripheral veins is covered in Chapter 22, The Extremities and Peripheral Vascular Exam, questions 41–62.

69 What is the clinical value of jugular venous distention and pulse?

It is a “poor man’s” monitor of right heart hemodynamics. More specifically:

Evaluation of jugular venous distention provides a noninvasive assessment of jugular venous pressure. This, in turn, provides an estimate of CVP and intravascular volume.

Evaluation of jugular venous distention provides a noninvasive assessment of jugular venous pressure. This, in turn, provides an estimate of CVP and intravascular volume.

Evaluation of jugular waveform provides instead additional information on right ventricular function, the status of the tricuspid and pulmonic valves, and the presence (or absence) of pericardial constriction.

Evaluation of jugular waveform provides instead additional information on right ventricular function, the status of the tricuspid and pulmonic valves, and the presence (or absence) of pericardial constriction.

72 Can the external jugulars be used for evaluating central venous pressure?

Theoretically not, practically yes. “Not” because:

While going through the various fascial planes of the neck, they often become compressed.

While going through the various fascial planes of the neck, they often become compressed.

In patients with increased sympathetic vascular tone, they may become so constricted as to be barely visible.

In patients with increased sympathetic vascular tone, they may become so constricted as to be barely visible.

They are farther away from the right atrium and thus in a less straight line with it. Yet, both internal and external jugular veins can actually be used for estimating CVP since they yield comparable estimates.

They are farther away from the right atrium and thus in a less straight line with it. Yet, both internal and external jugular veins can actually be used for estimating CVP since they yield comparable estimates.

73 But don’t external jugulars have valves?

They do, but so do the internal jugulars. Yet, this doesn’t interfere with estimation of CVP since the normal flow of blood is toward the heart, and not from it. It might interfere, though, with the evaluation of the venous pulse (see question 79).

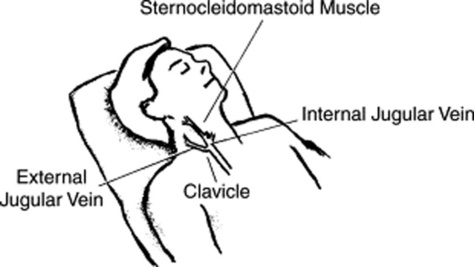

75 What is the anatomy of internal and external jugular veins?

The external jugulars lie above the sternocleidomastoid muscles, coursing obliquely from behind and laterally toward the angle of the jaw (Fig. 10-6). The internal jugulars lie instead below the sternocleidomastoids, crossing them in a vertical straight line. At the junction with the subclavian veins, the internal jugulars create a dilation known as the bulb, which is often visible between the two heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscles.

77 How important is the patient’s position during examination of the neck veins?

The head should be supported, so that the neck muscles are fully relaxed and not impinging on the jugular veins.

The head should be supported, so that the neck muscles are fully relaxed and not impinging on the jugular veins.

The trunk should be inclined and raised. The angle of inclination must allow the top of the column of blood in the internal jugular to reach above the clavicle, but still to remain below the jaw. This inclination will vary depending on CVP:

The trunk should be inclined and raised. The angle of inclination must allow the top of the column of blood in the internal jugular to reach above the clavicle, but still to remain below the jaw. This inclination will vary depending on CVP:

In patients with normal CVP, the required angle is usually 30–45 degrees above the horizontal.

In patients with normal CVP, the required angle is usually 30–45 degrees above the horizontal.

In patients with elevated CVP, the required angle is >45 degrees. In fact, patients with severe venous congestion may have to sit upright and take deep inspiration in order to lower the meniscus down into full view. In some of these patients, the level of venous pulsation may still remain behind the angle of the jaw, where it will appear to flicker the earlobes.

In patients with elevated CVP, the required angle is >45 degrees. In fact, patients with severe venous congestion may have to sit upright and take deep inspiration in order to lower the meniscus down into full view. In some of these patients, the level of venous pulsation may still remain behind the angle of the jaw, where it will appear to flicker the earlobes.

In patients with very high CVP, the internal jugular will be so “full” that pulsations may not be visible even when the patient is fully upright. The risk in this case is to overlook the high venous pressure and call it normal.

In patients with very high CVP, the internal jugular will be so “full” that pulsations may not be visible even when the patient is fully upright. The risk in this case is to overlook the high venous pressure and call it normal.

In patients with low CVP, the required angle is usually between 0 and 30 degrees.

In patients with low CVP, the required angle is usually between 0 and 30 degrees.

In patients with very low CVP, the neck veins will be so empty that pulsations may not be visible at all, even when the patient is fully horizontal.

In patients with very low CVP, the neck veins will be so empty that pulsations may not be visible at all, even when the patient is fully horizontal.

78 How do you tell apart the carotid pulse from the jugular venous pulse?

By the following differentiating features:

The waveform is different: The venous pulsation is diffuse, at least bifid, and with a slow upward deflection. Conversely, the carotid pulse is well localized, single, and with a fast outward deflection. Also, the most striking event in the venous pulse is the troughs, whereas in the arterial pulse, it is the ascent.

The waveform is different: The venous pulsation is diffuse, at least bifid, and with a slow upward deflection. Conversely, the carotid pulse is well localized, single, and with a fast outward deflection. Also, the most striking event in the venous pulse is the troughs, whereas in the arterial pulse, it is the ascent.

The response to position is different: The carotid pulse never varies with position. The venous pulsations classically do so. In fact, as the patient sits up or stands, they move down toward the clavicle and may even disappear below it. Conversely, as the patient reclines, venous pulsations gradually climb toward the angle of the jaw. They may even disappear behind the auricle.

The response to position is different: The carotid pulse never varies with position. The venous pulsations classically do so. In fact, as the patient sits up or stands, they move down toward the clavicle and may even disappear below it. Conversely, as the patient reclines, venous pulsations gradually climb toward the angle of the jaw. They may even disappear behind the auricle.

The response to respiration is different: In the absence of intrathoracic disease (and Kussmaul’s sign—see questions 115–118), the top of the venous waveform descends toward the heart during inspiration (because of lower intrathoracic pressure and greater venous return). The carotid pulse, instead, remains unchanged. The only exception is pulsus paradoxus, and even in this case, the variation is rarely visible, at most palpable. Note that inspiration makes jugular “pulsations” more visible (by enhancing venous return), even though it also lowers the mean jugular “pressure.”

The response to respiration is different: In the absence of intrathoracic disease (and Kussmaul’s sign—see questions 115–118), the top of the venous waveform descends toward the heart during inspiration (because of lower intrathoracic pressure and greater venous return). The carotid pulse, instead, remains unchanged. The only exception is pulsus paradoxus, and even in this case, the variation is rarely visible, at most palpable. Note that inspiration makes jugular “pulsations” more visible (by enhancing venous return), even though it also lowers the mean jugular “pressure.”

The response to palpation is different: The jugular venous pulse is too light to be palpable. Even gentle pressure will collapse the vein, engorge its more distal segment, and obliterate the pulse. Conversely, the carotid is not only palpable but quite forceful too.

The response to palpation is different: The jugular venous pulse is too light to be palpable. Even gentle pressure will collapse the vein, engorge its more distal segment, and obliterate the pulse. Conversely, the carotid is not only palpable but quite forceful too.

The response to abdominal pressure is different: Sustained pressure on the abdomen (the abdominojugular reflux test, see questions 106–114) will not change the carotid pulse, but will increase (at least momentarily) even the normal venous pulse (see Table 10-3).

The response to abdominal pressure is different: Sustained pressure on the abdomen (the abdominojugular reflux test, see questions 106–114) will not change the carotid pulse, but will increase (at least momentarily) even the normal venous pulse (see Table 10-3).

Table 10-3 Differentiation Between Jugular and Carotid Pulses

| Characteristic | Internal Jugular Vein and Jugular Venous Pulse | Carotid Artery and Carotid Pulse |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Low in neck and lateral | Deep in neck and medial |

| Contour | Double peaked and diffuse | Single peaked and sharp |

| Character | Undulant, not palpable | Forceful, brisk, easily felt |

| Response to position | Varies with position | No variation |

| Response to respiration | Mean pressure decreases on inspiration (height of column falls), but A and V waves become more visible | No variation |

| Response to abdominal pressure | Displaces pulse upward and induces transient increase in mean pressure | Pulse unchanged |

| Effect of palpation | Wave visible but nonpalpable | Pulse unchanged |

| Gentle pressure 3–4 cm above the clavicle obliterates pulse and fills the vein | Vessel difficult to compress |

(Adapted from Cook DJ, Simel N: Does this patient have abnormal central venous pressure? JAMA 275:630–634, 1996; and Abrams J: Essentials of Cardiac Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1987.)

79 How do you evaluate the jugular venous pulse?

With great difficulty and lots of practice.

Examine the right internal jugular vein (which is in more direct line with the right atrium).

Examine the right internal jugular vein (which is in more direct line with the right atrium).

Position the patient at such an angle that the jugular meniscus (i.e., the top of the venous flickering) is well seen. Shine a light tangentially to better visualize the flickering.

Position the patient at such an angle that the jugular meniscus (i.e., the top of the venous flickering) is well seen. Shine a light tangentially to better visualize the flickering.

Carefully inspect the level of the venous column and the timing and amplitude of the waveform and its components. Note respiratory variations (see questions 84 and 85).

Carefully inspect the level of the venous column and the timing and amplitude of the waveform and its components. Note respiratory variations (see questions 84 and 85).

80 What are the components of the jugular waveform?

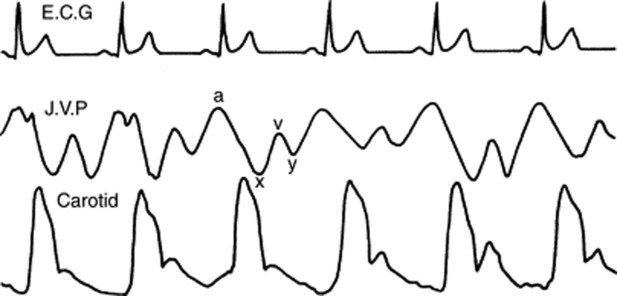

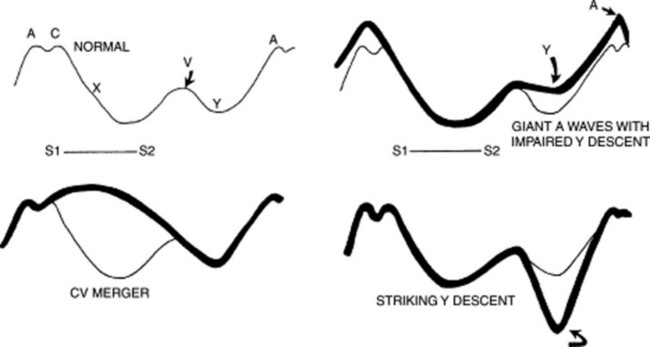

On venous tracing, the jugular pulse consists of three positive waves (A, C, and V) and three negative descents (X, X1, and Y). The A wave is followed by the X descent, the C wave by the X1 descent, and the V wave by the Y descent.

On venous tracing, the jugular pulse consists of three positive waves (A, C, and V) and three negative descents (X, X1, and Y). The A wave is followed by the X descent, the C wave by the X1 descent, and the V wave by the Y descent.

At the bedside, the jugular venous pulse consists instead of only two positive waves (A and V—with A taller than V) and two negative descents (X1 and Y—with X1 steeper than Y). Neither the C wave nor the X descent is visible (C is usually lost in the A wave, and X is merged with X1). Note that descents are easier to spot than ascents (see Fig. 10-7).

At the bedside, the jugular venous pulse consists instead of only two positive waves (A and V—with A taller than V) and two negative descents (X1 and Y—with X1 steeper than Y). Neither the C wave nor the X descent is visible (C is usually lost in the A wave, and X is merged with X1). Note that descents are easier to spot than ascents (see Fig. 10-7).

82 What is the physiology of the various ascents and descents of the jugular venous pulse?

The A wave (the first and dominant positive wave) is produced by right atrial contraction. It follows the P wave on ECG, coincides with the fourth heart sound (if present), and slightly precedes both the first heart sound and carotid upstroke.

The A wave (the first and dominant positive wave) is produced by right atrial contraction. It follows the P wave on ECG, coincides with the fourth heart sound (if present), and slightly precedes both the first heart sound and carotid upstroke.

The C wave, the second positive wave (only visible on recordings), is produced by the bulging of the tricuspid cusps into the right atrium and thus coincides with ventricular isovolumetric contraction. Note that a very small component of “C” is produced by the transmitted carotid pulsation—in fact, MacKenzie considered it an entirely carotid artifact; hence, the label “C”). Also, note that the interval between A and C corresponds to the P–R interval on ECG (this was one of the methods used by Wenckebach to describe the second-degree heart block that still carries his name). Yet, since the C wave is not visible at the bedside, it will be omitted from the remainder of our discussion.

The C wave, the second positive wave (only visible on recordings), is produced by the bulging of the tricuspid cusps into the right atrium and thus coincides with ventricular isovolumetric contraction. Note that a very small component of “C” is produced by the transmitted carotid pulsation—in fact, MacKenzie considered it an entirely carotid artifact; hence, the label “C”). Also, note that the interval between A and C corresponds to the P–R interval on ECG (this was one of the methods used by Wenckebach to describe the second-degree heart block that still carries his name). Yet, since the C wave is not visible at the bedside, it will be omitted from the remainder of our discussion.

The early X descent (located between A and C) is produced by right atrial relaxation. The most dominant later trough (X1 [i.e., the “x-prime”]) is produced instead by the pulling of the valvular cusps into the right ventricle. This downward and forward movement of valve and atrium floor (descent of the base) coincides with right ventricular isotonic contraction and acts as a plunger, creating a sucking effect that draws blood from the great veins into the right atrium. The X1 descent occurs during systole, coincides with ventricular ejection and the carotid pulse, takes place between S1 and S2, and ends just before S2. Note that this discussion disregards the early X descent and uses instead this term to refer to the combined X and X1 troughs—the only one visible at the bedside.

The early X descent (located between A and C) is produced by right atrial relaxation. The most dominant later trough (X1 [i.e., the “x-prime”]) is produced instead by the pulling of the valvular cusps into the right ventricle. This downward and forward movement of valve and atrium floor (descent of the base) coincides with right ventricular isotonic contraction and acts as a plunger, creating a sucking effect that draws blood from the great veins into the right atrium. The X1 descent occurs during systole, coincides with ventricular ejection and the carotid pulse, takes place between S1 and S2, and ends just before S2. Note that this discussion disregards the early X descent and uses instead this term to refer to the combined X and X1 troughs—the only one visible at the bedside.

The V wave (the third positive wave) occurs toward the end of ventricular systole and during the early phase of ventricular diastole. It coincides with the apex of the carotid pulse and peaks immediately after S2. Because the ventricle relaxes while the tricuspid valve is still closed, blood flowing into the right atrium starts building up, generating a positive wave.

The V wave (the third positive wave) occurs toward the end of ventricular systole and during the early phase of ventricular diastole. It coincides with the apex of the carotid pulse and peaks immediately after S2. Because the ventricle relaxes while the tricuspid valve is still closed, blood flowing into the right atrium starts building up, generating a positive wave.

The Y descent (the final negative trough) occurs during early ventricular diastole. It is due to the opening of the tricuspid valve and the emptying of the right atrium. It corresponds to S3.

The Y descent (the final negative trough) occurs during early ventricular diastole. It is due to the opening of the tricuspid valve and the emptying of the right atrium. It corresponds to S3.

85 What is the influence of respiration on the jugular venous pressure?

The opposite. Inspiration lowers the mean jugular venous pressure, exhalation increases it.

86 Which diseases can be diagnosed by jugular venous pulse?

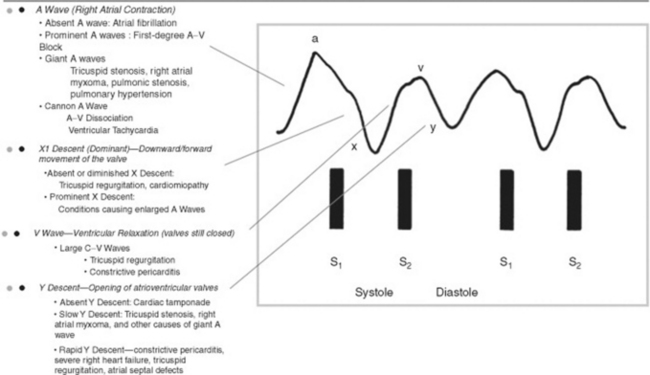

Quite a few. Some are both common and important, affecting either waves or descents (see Fig. 10-8).

87 What are the most important abnormalities of jugular waves?

For both this and the next question, see Fig. 10-9.

Giant A wave. In addition to tricuspid stenosis, this also can occur in increased right ventricular end-diastolic pressure (from pulmonic stenosis, primary pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary emboli, or chronic pulmonary disease). In these patients, the large A wave reflects a strong atrial contraction against a stiffer ventricle presenting with a concomitantly blunted and small Y descent. The acoustic counterpart of a giant A wave is a right-sided S4, and its electric equivalent is a P pulmonale. Giant A waves also may be seen in marked left ventricular hypertrophy (like AS, severe hypertension, or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy). In these patients, the ventricular septum bulges toward the right, making right ventricular filling more difficult (the Bernheim effect, from Hippolyte Bernheim, the French physician and hypnotist who described it in 1910).

Giant A wave. In addition to tricuspid stenosis, this also can occur in increased right ventricular end-diastolic pressure (from pulmonic stenosis, primary pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary emboli, or chronic pulmonary disease). In these patients, the large A wave reflects a strong atrial contraction against a stiffer ventricle presenting with a concomitantly blunted and small Y descent. The acoustic counterpart of a giant A wave is a right-sided S4, and its electric equivalent is a P pulmonale. Giant A waves also may be seen in marked left ventricular hypertrophy (like AS, severe hypertension, or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy). In these patients, the ventricular septum bulges toward the right, making right ventricular filling more difficult (the Bernheim effect, from Hippolyte Bernheim, the French physician and hypnotist who described it in 1910).

“Cannon” A wave is the hallmark of atrioventricular dissociation (i.e., the atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve). It is different from the other prominent outward wave (i.e., the presystolic giant A wave), insofar as it begins just after S1, since it represents atrial contraction against a closed tricuspid valve. The giant A wave, on the other hand, begins just before S1—like the large V wave of tricuspid regurgitation (see below). Intermittent cannon A waves reflect atrioventricular dissociation in a setting of ventricular tachycardia, whereas regular cannon A waves reflect atrioventricular dissociation in a setting of supraventricular tachycardia with retrograde atrial activation.

“Cannon” A wave is the hallmark of atrioventricular dissociation (i.e., the atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve). It is different from the other prominent outward wave (i.e., the presystolic giant A wave), insofar as it begins just after S1, since it represents atrial contraction against a closed tricuspid valve. The giant A wave, on the other hand, begins just before S1—like the large V wave of tricuspid regurgitation (see below). Intermittent cannon A waves reflect atrioventricular dissociation in a setting of ventricular tachycardia, whereas regular cannon A waves reflect atrioventricular dissociation in a setting of supraventricular tachycardia with retrograde atrial activation.

The V wave is classically increased in tricuspid regurgitation (TR), during which it becomes the dominant wave, associated with a brisk Y collapse (a more gentle Y descent usually indicates concomitant regurgitation and stenosis). Abdominal compression may help to unmask more subtle and subclinical cases. Prominent V waves can become so large that they were dubbed by Paul Wood “the venous Corrigan.” In fact, they may even cause bobbing of the earlobes (the Lancisi’s sign). Since the C and V merger responsible for the giant V wave entirely eliminates the X descent, a giant wave is easy to spot: it starts just after S1 and leaves the patient with only one ascent (the V wave) and one descent (the Y descent). The giant V wave is not too sensitive for tricuspid regurgitation (TR), being present in only 40% of the cases.

The V wave is classically increased in tricuspid regurgitation (TR), during which it becomes the dominant wave, associated with a brisk Y collapse (a more gentle Y descent usually indicates concomitant regurgitation and stenosis). Abdominal compression may help to unmask more subtle and subclinical cases. Prominent V waves can become so large that they were dubbed by Paul Wood “the venous Corrigan.” In fact, they may even cause bobbing of the earlobes (the Lancisi’s sign). Since the C and V merger responsible for the giant V wave entirely eliminates the X descent, a giant wave is easy to spot: it starts just after S1 and leaves the patient with only one ascent (the V wave) and one descent (the Y descent). The giant V wave is not too sensitive for tricuspid regurgitation (TR), being present in only 40% of the cases.

Equally prominent A and V waves can occur in atrial septal defect, wherein the V wave in the higher-pressure left atrium is transmitted through the perforated septum into the right atrium, and from there to the jugular veins. Still, equally prominent A and V waves are much more commonly suggestive of simple right ventricular failure.

Equally prominent A and V waves can occur in atrial septal defect, wherein the V wave in the higher-pressure left atrium is transmitted through the perforated septum into the right atrium, and from there to the jugular veins. Still, equally prominent A and V waves are much more commonly suggestive of simple right ventricular failure.

88 What are the most important abnormalities of jugular descents?

A prominent X descent is seen in patients with vigorous ventricular contraction (and thus requiring strong atrial contractions), like tamponade or right ventricular overload.

A prominent X descent is seen in patients with vigorous ventricular contraction (and thus requiring strong atrial contractions), like tamponade or right ventricular overload.

A diminished X descent (to the point of becoming even less prominent than the Y descent) is seen in atrial fibrillation or cardiomyopathy (wherein right ventricular contraction is not forceful enough to “pull down” the atrial floor). TR, of course, would obliterate the X descent.

A diminished X descent (to the point of becoming even less prominent than the Y descent) is seen in atrial fibrillation or cardiomyopathy (wherein right ventricular contraction is not forceful enough to “pull down” the atrial floor). TR, of course, would obliterate the X descent.

A prominent Y descent is seen in patients with increased venous pressure, regardless of etiology. A very brisk Y descent is often referred to as Friedreich’s sign, from the German clinician and neurologist, Nikolaus Friedreich, who described it in 1864. In combination with the prominent X descent, it creates two steep troughs (the “W” sign). This occurs in one third of constrictive pericarditis cases, where it is often associated with an early diastolic extra sound (pericardial knock). Friedreich’s sign is not too sensitive for constrictive pericarditis, but quite specific, with the only differential diagnosis being restrictive cardiomyopathy.

A prominent Y descent is seen in patients with increased venous pressure, regardless of etiology. A very brisk Y descent is often referred to as Friedreich’s sign, from the German clinician and neurologist, Nikolaus Friedreich, who described it in 1864. In combination with the prominent X descent, it creates two steep troughs (the “W” sign). This occurs in one third of constrictive pericarditis cases, where it is often associated with an early diastolic extra sound (pericardial knock). Friedreich’s sign is not too sensitive for constrictive pericarditis, but quite specific, with the only differential diagnosis being restrictive cardiomyopathy.

A diminished-to-absent Y descent is seen in patients with increased central venous pressure, like tamponade or tricuspid stenosis. Note that the Y descent is usually minimal in normal subjects, too; hence, an abnormally diminished Y descent has clinical significance only if the patient has high central venous pressure.

A diminished-to-absent Y descent is seen in patients with increased central venous pressure, like tamponade or tricuspid stenosis. Note that the Y descent is usually minimal in normal subjects, too; hence, an abnormally diminished Y descent has clinical significance only if the patient has high central venous pressure.

89 How do you estimate the CVP?

By positioning the patient so that you can get a good view of the internal jugular vein and its oscillations. Although it is wise to start at 45 degrees, it doesn’t really matter which angle you will eventually use to raise the patient’s head, as long as it can adequately reveal the vein. In the absence of a visible internal jugular, the external jugular may suffice.

By positioning the patient so that you can get a good view of the internal jugular vein and its oscillations. Although it is wise to start at 45 degrees, it doesn’t really matter which angle you will eventually use to raise the patient’s head, as long as it can adequately reveal the vein. In the absence of a visible internal jugular, the external jugular may suffice.

By identifying the highest point of jugular pulsation that is transmitted to the skin (i.e., the meniscus). This usually occurs during exhalation and coincides with the peak of “A” or “V” waves. It serves as a bedside pulsation manometer.

By identifying the highest point of jugular pulsation that is transmitted to the skin (i.e., the meniscus). This usually occurs during exhalation and coincides with the peak of “A” or “V” waves. It serves as a bedside pulsation manometer.

By finding the sternal angle of Louis (junction of the manubrium with the body of the sternum). This provides the standard zero for jugular venous pressure (the standard zero for the “central” venous pressure is instead the center of the right atrium).

By finding the sternal angle of Louis (junction of the manubrium with the body of the sternum). This provides the standard zero for jugular venous pressure (the standard zero for the “central” venous pressure is instead the center of the right atrium).

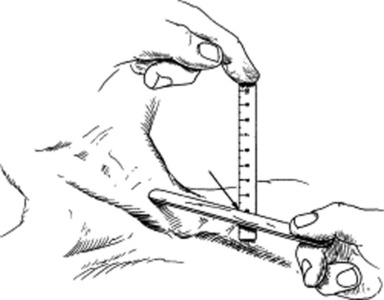

By measuring in centimeters the vertical height from the sternal angle to the top of the jugular pulsation. To do so, place two rulers at a 90-degree angle: one horizontal (and parallel to the meniscus) and the other vertical to it and touching the sternal angle (see Fig. 10-10). The extrapolated height between the sternal angle and meniscus represents the jugular venous pressure (JVP).

By measuring in centimeters the vertical height from the sternal angle to the top of the jugular pulsation. To do so, place two rulers at a 90-degree angle: one horizontal (and parallel to the meniscus) and the other vertical to it and touching the sternal angle (see Fig. 10-10). The extrapolated height between the sternal angle and meniscus represents the jugular venous pressure (JVP).

By adding five to convert jugular venous pressure into central venous pressure.

By adding five to convert jugular venous pressure into central venous pressure.

93 Are there alternative methods to assess the CVP?

Yes, but they have not been validated:

Von Recklinghausen’s maneuver consists in asking the patient to lie supine, with the palm of one hand laid down over the thigh, and the other laid down over the bed (thereby 5–10 cm below the first hand). Patients have high CVP if the veins of both hands are engorged but normal CVP if only the lower hand veins are engorged.

Von Recklinghausen’s maneuver consists in asking the patient to lie supine, with the palm of one hand laid down over the thigh, and the other laid down over the bed (thereby 5–10 cm below the first hand). Patients have high CVP if the veins of both hands are engorged but normal CVP if only the lower hand veins are engorged.

An alternative but similar maneuver consists in inspecting the veins of the back of the hand in a reclining patient as the arm is slowly and passively raised. The level at which the veins collapse can then be related to the angle of Louis and the CVP measured.

An alternative but similar maneuver consists in inspecting the veins of the back of the hand in a reclining patient as the arm is slowly and passively raised. The level at which the veins collapse can then be related to the angle of Louis and the CVP measured.

94 How precise is the clinical assessment of CVP?

In a study of 50 intensive care unit patients, agreement on CVP values was substantial between students and residents, moderate between students and attending physicians, and modest between residents and staff. Factors that interfered with the precision of the estimate included variations in patients’ positioning, poor ambient lighting, confusion between carotid and venous pulsations, and changes in CVP with respiration.

In a study of 50 intensive care unit patients, agreement on CVP values was substantial between students and residents, moderate between students and attending physicians, and modest between residents and staff. Factors that interfered with the precision of the estimate included variations in patients’ positioning, poor ambient lighting, confusion between carotid and venous pulsations, and changes in CVP with respiration.

In a second study, an attending physician, a critical care fellow, a medical resident, an intern, and a student were asked to predict whether the CVP of 62 patients was low, normal, high, or very high. Right heart catheterization provided the gold standard. The sensitivity of clinical examination was 0.33, 0.33, and 0.49, respectively for the identification of low (<0 mmHg), normal (0 to 7 mmHg), or high (>7 mmHg) CVP. The specificity of the exam was instead 0.73, 0.62, and 0.76, respectively. Accuracy was greater in patients with low cardiac indexes (<2.2 L/min) and high pulmonary artery wedge pressures (>18 mmHg). It was lower in comatose patients or patients on mechanical ventilation. A higher precision (i.e., interobserver agreement) did not translate into a greater accuracy.

In a second study, an attending physician, a critical care fellow, a medical resident, an intern, and a student were asked to predict whether the CVP of 62 patients was low, normal, high, or very high. Right heart catheterization provided the gold standard. The sensitivity of clinical examination was 0.33, 0.33, and 0.49, respectively for the identification of low (<0 mmHg), normal (0 to 7 mmHg), or high (>7 mmHg) CVP. The specificity of the exam was instead 0.73, 0.62, and 0.76, respectively. Accuracy was greater in patients with low cardiac indexes (<2.2 L/min) and high pulmonary artery wedge pressures (>18 mmHg). It was lower in comatose patients or patients on mechanical ventilation. A higher precision (i.e., interobserver agreement) did not translate into a greater accuracy.

In a third study, Eisenberg and colleagues compared bedside assessment of 97 critically ill patients with pulmonary artery catheter readings. They compared various hemodynamic variables, including CVP. Based on clinical assessment, physicians were asked to predict whether the CVP was <2, 2–6, or >6 mmHg. Predictions were correct only 55% of the time. CVP was underestimated more frequently than overestimated (27% and 17% respectively).

In a third study, Eisenberg and colleagues compared bedside assessment of 97 critically ill patients with pulmonary artery catheter readings. They compared various hemodynamic variables, including CVP. Based on clinical assessment, physicians were asked to predict whether the CVP was <2, 2–6, or >6 mmHg. Predictions were correct only 55% of the time. CVP was underestimated more frequently than overestimated (27% and 17% respectively).

95 So what conclusions can be drawn about the clinical use of CVP assessment?

When compared to the gold standard of a central venous catheter, clinical measurement of CVP is overall poor, especially in the acutely ill patient. In the aforementioned study of 50 critically ill patients, for example, the pooled accuracy of the test was 56%. All groups involved (students, residents, and attending physicians) tended to underestimate central venous pressure (see question 96), and level of expertise was not a guarantee of accuracy. In fact, the correlation coefficient between clinical assessment and central venous catheter recording was highest for medical students (0.74), a little lower for residents (0.71), and lowest for staff physicians (0.65). These correlations slightly improved after exclusion of patients on mechanical ventilation, suggesting that CVP assessment is more accurate in patients who breathe spontaneously. Hence, bedside assessment of CVP is only accurate at the extremes of presentation:

A low CVP increases the likelihood by threefold that the measured CVP will also be low. It also makes it very unlikely that the measured CVP will be high.

A low CVP increases the likelihood by threefold that the measured CVP will also be low. It also makes it very unlikely that the measured CVP will be high.

A high CVP at the bedside (because of neck veins distended more than 3 cm above the angle of Louis) increases the likelihood by about fourfold that the measured CVP will also be high. In fact, no patient with a clinically high CVP had a low measured CVP.

A high CVP at the bedside (because of neck veins distended more than 3 cm above the angle of Louis) increases the likelihood by about fourfold that the measured CVP will also be high. In fact, no patient with a clinically high CVP had a low measured CVP.

Finally, a CVP assessed as normal at the bedside is truly indeterminate (with likelihood ratios approaching 1). Thus, clinical estimates of “normal” CVP provide no helpful information because they neither increase nor decrease the probability of an abnormal CVP.

Finally, a CVP assessed as normal at the bedside is truly indeterminate (with likelihood ratios approaching 1). Thus, clinical estimates of “normal” CVP provide no helpful information because they neither increase nor decrease the probability of an abnormal CVP.

98 What is the significance of an elevated jugular venous pressure?

Superior vena cava obstruction (in this case, there will be no jugular venous pulse and the abdominojugular reflux test will be negative).

Superior vena cava obstruction (in this case, there will be no jugular venous pulse and the abdominojugular reflux test will be negative).

Obstruction to right ventricular inflow (such as tricuspid stenosis and right atrial myxoma, but also constrictive pericarditis or tamponade, where neck vein distention is a sine qua non)

Obstruction to right ventricular inflow (such as tricuspid stenosis and right atrial myxoma, but also constrictive pericarditis or tamponade, where neck vein distention is a sine qua non)

Decreased right ventricular compliance with increased end-diastolic (and right atrial) pressure. Possible causes include right ventricular failure or infarction, pulmonic stenosis, and pulmonary hypertension.

Decreased right ventricular compliance with increased end-diastolic (and right atrial) pressure. Possible causes include right ventricular failure or infarction, pulmonic stenosis, and pulmonary hypertension.

Left ventricular failure. This is a common cause of pulmonary hypertension. In fact, in patients presenting with either angina or dyspnea, a high CVP argues in favor of left ventricular failure. Conversely, normal neck veins are unhelpful in separating normal from increased left-atrial pressure.

Left ventricular failure. This is a common cause of pulmonary hypertension. In fact, in patients presenting with either angina or dyspnea, a high CVP argues in favor of left ventricular failure. Conversely, normal neck veins are unhelpful in separating normal from increased left-atrial pressure.

101 How are the neck veins in tamponade?

Distended. This is a must, together with dyspnea/tachypnea, tachycardia, and clear lungs. Given this constellation of four symptoms/findings, the differential diagnosis is narrowed to five major entities: right ventricular infarction, massive pulmonary embolism, constrictive pericarditis, tension pneumothorax, and tamponade. The first four present with a positive Kussmaul’s sign in approximately one half of the cases, but never have a pulsus paradoxus >21 mmHg. Conversely, tamponade comes with no Kussmaul’s, but does present with a pulsus of 20–50 mmHg (see Chapter 2, questions 92–95).

104 What is the prognostic value of an increased CVP in preoperative patients?

If untreated, it predicts postoperative pulmonary edema and/or infarction.

105 What are the jugular findings of right ventricular infarction?

The right ventricular filling pressure is increased (as a result of an ischemic and less compliant chamber). Since the ventricle also becomes unable to handle incoming venous flow, the mean jugular (and central) venous pressures will be similarly increased. This has high specificity (96.8%) but low sensitivity (39%) for right ventricular infarction.

The right ventricular filling pressure is increased (as a result of an ischemic and less compliant chamber). Since the ventricle also becomes unable to handle incoming venous flow, the mean jugular (and central) venous pressures will be similarly increased. This has high specificity (96.8%) but low sensitivity (39%) for right ventricular infarction.

The jugular venous pulse exhibits a prominent “A” wave. It also shows “X” and “Y” descents so steep as to almost mimic constrictive pericarditis. Still, despite its high specificity (100%), a rapid “Y” descent has low sensitivity (17.3%) for right ventricular infarction. Moreover, jugular venous pressure and waveform are both significantly affected by the concomitant magnitude of damage to the interventricular septum and left ventricular free wall.

The jugular venous pulse exhibits a prominent “A” wave. It also shows “X” and “Y” descents so steep as to almost mimic constrictive pericarditis. Still, despite its high specificity (100%), a rapid “Y” descent has low sensitivity (17.3%) for right ventricular infarction. Moreover, jugular venous pressure and waveform are both significantly affected by the concomitant magnitude of damage to the interventricular septum and left ventricular free wall.

Positive Kussmaul’s sign is as specific as a JVP increase, but less sensitive (26.1%).

Positive Kussmaul’s sign is as specific as a JVP increase, but less sensitive (26.1%).

The abdominojugular reflux test can be positive.

The abdominojugular reflux test can be positive.

Finally, an associated tricuspid regurgitation (TR) will give additional findings, such as giant V waves, pulsatile liver, and right earlobe bobbing.

Finally, an associated tricuspid regurgitation (TR) will give additional findings, such as giant V waves, pulsatile liver, and right earlobe bobbing.

107 What is it used for?

To unmask subclinical right ventricular failure (and silent tricuspid regurgitation) but also to confirm symptomatic left ventricular failure (see question 113). Hence, the “Pasteur-Rondot maneuver” is a very helpful tool, albeit one that is often misused and misinterpreted.

111 How do you perform an abdominojugular test?

By observing the jugular venous pressure before, during, and after abdominal compression:

Position the supine patient so that the jugular venous pulsations are properly monitored (an angle of 45 degrees will usually suffice). Then instruct the patient to relax and breathe normally through the open mouth. This will avoid the false positive increase in jugular venous pressure caused by a Valsalva’s maneuver inadvertently triggered by abdominal discomfort.

Position the supine patient so that the jugular venous pulsations are properly monitored (an angle of 45 degrees will usually suffice). Then instruct the patient to relax and breathe normally through the open mouth. This will avoid the false positive increase in jugular venous pressure caused by a Valsalva’s maneuver inadvertently triggered by abdominal discomfort.

Apply your hand over the patient’s mid abdomen (periumbilical area), with fingers widely spread and palm gently rested. Once the patient is well relaxed, apply gradual and progressive pressure for at least 15 seconds: firm, inward, cephalad, and soon reaching a steady level of 20–35 mmHg. This can be confirmed by placing an unrolled bladder of a standard adult blood pressure cuff between the examiner’s hand and the patient’s abdomen. The cuff should be partially inflated with six full-bulb compressions.

Apply your hand over the patient’s mid abdomen (periumbilical area), with fingers widely spread and palm gently rested. Once the patient is well relaxed, apply gradual and progressive pressure for at least 15 seconds: firm, inward, cephalad, and soon reaching a steady level of 20–35 mmHg. This can be confirmed by placing an unrolled bladder of a standard adult blood pressure cuff between the examiner’s hand and the patient’s abdomen. The cuff should be partially inflated with six full-bulb compressions.

Note that the precision of the test may vary, based on the force of abdominal compression. Different investigators have in fact suggested different force: Ducas recommended 35 mmHg (equivalent to a weight of approximately 8 kg), whereas Ewy used 20 mmHg.

Note that the precision of the test may vary, based on the force of abdominal compression. Different investigators have in fact suggested different force: Ducas recommended 35 mmHg (equivalent to a weight of approximately 8 kg), whereas Ewy used 20 mmHg.

Throughout the maneuver (i.e., before, during, or after compression), observe the column of blood in the internal and external jugular veins.

Throughout the maneuver (i.e., before, during, or after compression), observe the column of blood in the internal and external jugular veins.

To avoid the risk of false positive neck vein distention from breath-holding or “bearing down,” consider a trial run. This also can be used to demonstrate in advance the force that will be applied onto the abdomen.

To avoid the risk of false positive neck vein distention from breath-holding or “bearing down,” consider a trial run. This also can be used to demonstrate in advance the force that will be applied onto the abdomen.

You might also look for a softening of the first heart sound during the application of abdominal pressure. This represents the auscultatory equivalent of a positive response.

You might also look for a softening of the first heart sound during the application of abdominal pressure. This represents the auscultatory equivalent of a positive response.

112 When is the abdominojugular test considered positive?

Sustained change, but not large enough (i.e., <3 cm)

Sustained change, but not large enough (i.e., <3 cm)

Enough change, but not sustained. In this case, there may be an initial bulging of the external jugular vein at the beginning of abdominal compression (and also of the peaks and troughs of the internal jugular), and the JVP may even increase by more than 3 cm, but this is transient and returns to normal (or near normal) during the remainder of the compression.

Enough change, but not sustained. In this case, there may be an initial bulging of the external jugular vein at the beginning of abdominal compression (and also of the peaks and troughs of the internal jugular), and the JVP may even increase by more than 3 cm, but this is transient and returns to normal (or near normal) during the remainder of the compression.

116 Which disease processes are associated with a positive Kussmaul’s?

120 What is the “venous hum”?

It is a functional murmur (see Chapter 12, questions 44 and 45) produced by turbulent flow in the internal jugular vein. It is continuous (albeit louder in diastole) and at times strong enough to be associated with a palpable thrill. It is best heard on the right side of the neck, just above the clavicle, but sometimes it can become audible over the sternal/parasternal areas, both right and left. This may lead to misdiagnoses of carotid disease, patent ductus arteriosus, or AR/AS.

E. The Precordial Movement and Impulse

129 How do you assess the precordial impulse(s)?

First inspect, since this may prove even more valuable than palpation. Shine a tangential light across the chest, which can help you visualize retractions and outward motions.

First inspect, since this may prove even more valuable than palpation. Shine a tangential light across the chest, which can help you visualize retractions and outward motions.

Then palpate the precordium, thoroughly assessing all major areas. With the patient in the supine position, localize impulses and evaluate their force. Then assess the impulse size by asking the patient to lie in left lateral decubitus. This also might help you elicit an otherwise undetectable apical impulse, as well as other impulses, such as a palpable S3 or S4. Use your palm to detect heaves or lifts (i.e., sustained precordial movements), the proximal metacarpals to identify thrills, and the finger pads to localize the various abnormalities. To clarify semantics, note that a heave/lift is a forceful and sustained systolic thrust that raises the palpating hand a little. The three terms are often used interchangeably.