Chapter 15 The cardiovascular system

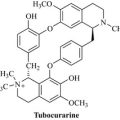

Cardiovascular (CV) disorders are responsible for many deaths in the Western world, and are a consequence of lifestyle and diet, as well as being hereditary to some extent. Serious conditions such as heart failure should be treated only under the guidance of a qualified physician, but some minor forms of CV disease respond well to changes in diet and taking more exercise, as well as phytotherapy. Cardiology has benefited greatly from the introduction of some newer semi-synthetic drugs based on natural products, including aspirin, an antiplatelet agent derived from salicin, and warfarin, an anticoagulant derived from dicoumarol. Others have been developed using a natural product as a template, for example, verapamil, a calcium channel antagonist used to treat hypertension and angina, is based on the opium alkaloid papaverine, and nifedipine, a calcium channel antagonist and amiodarone, an anti-arrhythmic, were both developed from khellin, the active constituent of Ammi visnaga. Cocaine has cardioactive as well as central nervous system effects, and was the starting material for the development of the anti-arrhythmics procaine and lignocaine, which are more effective and without the unwanted stimulant activity (Hollmann 1992).

Cardiovascular conditions discussed here include heart failure, venous insufficiency, thrombosis and atherosclerosis. Other conditions such as hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias are rarely treated with phytomedicines, although there are some natural products used in their treatment which will be mentioned briefly. Synthetic diuretics are widely used as antihypertensives, but phytomedicines are not suitable for this purpose as they are not sufficiently potent to reduce blood pressure. Instead, they are often incorporated into remedies for urinary tract complaints (see Chapter 20) or to reduce bloating (mild water retention, for example pre-menstrual).

Heart failure and arrhythmias

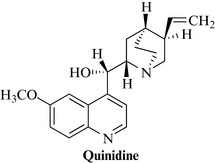

There are, however, other herbal drugs that have beneficial effects upon the heart, the most important of which are hawthorn (Crataegus) and motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca). Hawthorn has anti-arrhythmic activity, and will be discussed briefly below. There is not enough evidence available at present to justify the inclusion of motherwort. In general, however, arrhythmias are treated with isolated compounds, most of which are synthetic, although quinidine (an alkaloid from Cinchona spp.; Fig. 15.1) is still used occasionally. Ajmaline, from Rauvolfia spp., is used as an anti-arrhythmic in some parts of the world; sparteine, from broom (Cytisus scoparius), was formerly employed. Both of these compounds are alkaloids.

Foxglove (digitalis) leaf, Digitalis purpurea L. (Digitalis purpureae folium)

Constituents

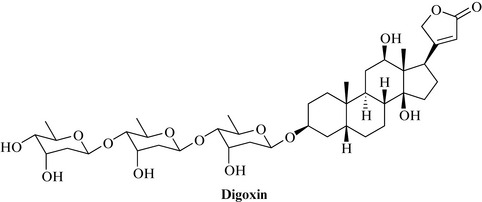

Both species contain cardenolides, which are glycosides of the steroidal aglycones digitoxigenin, gitoxigenin and gitaloxigenin. There are very many cardiac glycosides, but the most important is digoxin (Fig. 15.2) and to a much lesser extent digitoxin, and the purpurea glycosides A and B. Digitalis lanata contains higher concentrations of glycosides, including digoxin and lanatosides, and is the main source of digoxin for the pharmaceutical industry.

Hawthorn, Crataegus spp. (Crataegi folium cum flore, Crataegi fructus)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Hawthorn is used as a cardiac tonic, hypotensive, coronary and peripheral vasodilator, anti-atherosclerotic and anti-arrhythmic. Animal studies have shown beneficial effects on coronary blood flow, blood pressure and heart rate, as well as improved circulation to the extremities (Alternative Medicine Review (Crataegus) 2010). Hawthorn extract inhibits myocardial Na+, K+-ATPase and exerts a positive inotropic effect and relaxes the coronary artery. It blocks the repolarizing potassium current in the ventricular muscle and so prolongs the refractory period, thus exerting an anti-arrhythmic effect. It seems to protect heart muscle by regulating Akt and HIF-1 signalling pathways (Jayachandran et al 2010), and reducing oxidative stress (Bernatoniene et al 2009, Swaminathan et al 2010). There are as yet few clinical trials of the drug, although a recent double-blind pilot study indicated a promising role for hawthorn extract in mild essential hypertension (Walker et al 2002). However, other studies have found that tolerance to exercise was not improved in patients with class II congestive heart failure (Zick et al 2009). It seems likely that hawthorn can be used as an adjunct or sole treatment only in milder cases of heart disease. The usual recommended dose of standardized extract (see Constituents, above) is 160–900 mg daily. Few side effects have been observed, and both patients and physicians rated the tolerance of the drug as good, although nausea and headache have been reported infrequently.

Venous insufficiency and circulatory disorders

Bilberry, Vaccinium myrtillus L. (Myrtilli fructus)

Constituents

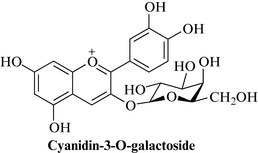

The fruit contains anthocyanosides (Fig. 15.3), mainly galactosides and glucosides of cyanidin, delphidin and malvidin, together with vitamin C and volatile flavour components such as trans-2-hexenal and ethyl-2- and -3-methylbutyrates. Unlike other Vaccinium spp., bilberry does not contain arbutin or other hydroquinone derivatives. The anthocyanins can be estimated using their absorption at 528 nm, as described in the Eur. Ph.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

The berries were traditionally used as an antidiabetic, and an astringent and antiseptic for diarrhoea. However, bilberry is now more important as an agent to improve blood circulation in venous insufficiency, especially for vision disorders such as retinopathy caused by diabetes or hypertension. The anthocyanosides are mainly responsible for these properties, due to their antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties. Other cardiovascular benefits include antiplatelet and anti-atherosclerotic effects. Bilberry extracts have a spasmolytic action on the gut and inhibit certain proteolytic enzymes. Anti-inflammatory, antiulcer effects have also been noted, and many of these have been supported by clinical studies (e.g. Christie et al 2001), although the quality of the trials for improving vision have been criticised for their methodology (Canter and Ernst 2004). The usual daily dose of a standardized anthocyanoside extract of bilberry is 480 mg, taken in divided doses. Few side effects have been observed, as would be expected of a widely consumed food substance.

Butcher’s broom, Ruscus aculeatus (Rusci rhizoma)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Butcher’s broom has anti-inflammatory effects and is used mainly for diseases of venous insufficiency, such as varicose veins and haemorrhoids. The ruscogenin constituents have been shown to reduce vascular permeability and improve symptoms of retinopathy and lipid profiles of diabetic patients. The extract is either taken internally as a decoction or, more often, applied topically in the form of an ointment (or a suppository in the case of haemorrhoids). The saponins inhibit elastase activity in vitro and for this reason extracts are widely used in cosmetic preparations (Redman 2000). When applied topically, few side effects have been observed, apart from occasional irritation.

Ginkgo, Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgo folium)

See Chapter 17 for more detail about the plant. Ginkgo biloba can also be used in cases of peripheral arterial occlusive disease and other circulatory disorders. Although probably less potent than some synthetic drugs, it has the advantage of being well tolerated. Ginkgo improves blood circulation and can alleviate some of the symptoms of tinnitus, intermittent claudication and altitude sickness. Ginkgo extracts have complex effects on isolated blood vessels. The ginkgolides are specific platelet-activating factor (PAF) antagonists and inhibit effects produced by PAF, including platelet aggregation and cerebral ischaemia. The usual dose is 120–160 mg of extract daily.

Horse chestnut, Aesculus hippocastaneum L. (Hippocastani semen)

Constituents

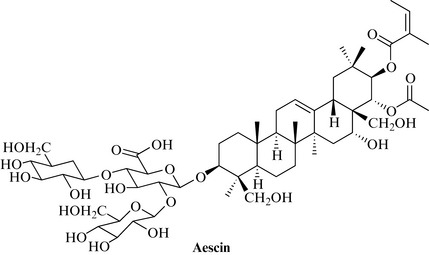

Both contain a complex mixture of saponins based on protoescigenin and barringtogenol-C, which is sometimes known as ‘aescin’ (or ‘escin’), although this term refers more properly to the isomeric compound aescin (see Fig. 15.4). More than 30 saponins have been identified, including α- and β-escin, together with escins Ia, Ib, IIa, IIb, IIIa, etc. Sterols and other triterpenes such friedelin, taraxerol and spinasterol are present, as well as coumarins (e.g. esculin=aesculin) and fraxin, flavonoids and anthocyanidins.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Extracts of horse chestnut, or, more usually, extracts standardized to the escin content, are used particularly for conditions involving chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), bruising and sports injuries. They can be taken internally or applied topically. A number of clinical studies have shown benefits in CVI (Pittler and Ernst 2006), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), including after surgery, varicose veins (including those of pregnancy) and for the prevention of oedema during a long (15 h) aeroplane flight. It was found to be beneficial in the treatment of cerebral oedema following road accidents. Venotonic effects, and an improvement in capillary resistance, have also been noted in healthy volunteers (Suter et al 2006). Escin has been shown to reduce oedema, decrease capillary permeability and increase venous tone, and horse chestnut extract to contract both veins and arteries in vitro, with veins being the more sensitive. The extract also significantly reduced ADP-induced human platelet aggregation, and these effects appear to be at least partly mediated through 5-HT(2A) receptors (Felixsson et al 2010). Horse chestnut extract also antagonizes some of the effects of bradykinin and produces an increase in plasma levels of adrenocorticotrophin, corticosterone and glucose in animals. Escin is widely used in cosmetics. The usual dose is 600 mg of extract daily, which corresponds to about 100 mg of escin. Extracts are well tolerated at therapeutic doses, but higher amounts can cause gastrointestinal upset with internal use, and occasional irritation with external application.

Red root sage, Salvia miltiorrhiza L. (Salviae miltiorrhizae radix)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Animal studies have shown many relevant effects, such as protecting heart muscle from ischaemia and improving microcirculation. The isolated tanshinones have been shown to reduce fever and inflammation, inhibit platelet aggregation, dilate the blood vessels and aid urinary excretion of toxins. Salvia miltiorrhiza has a mild vasodilatory effect but does not increase cardiac output. Clinical studies carried out in China have shown benefit to patients with heart and circulatory diseases, including ischaemic stroke and acute myocardial infarction, but many of these do not fulfil the criteria required for acceptance in the West, and the efficacy has, therefore, not been accepted there (Wu et al 2007, Wu et al 2008, Yu et al 2009). In general, Salvia miltiorrhiza seems to be safe and well-tolerated at the usual dose of 2–6 g day for the dried root, or equivalent in the form of an extract, but there is a potential for drug interactions, especially with other cardiovascular drugs (Williamson et al 2009).

Red vine leaf, Vitis vinifera L. (Vitis viniferae folium)

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Clinical studies have shown that the extract can improve objective symptoms of CVI and that it may prevent further CVI deterioration (Kalus et al 2004). Red vine leaf extracts are also used to improve the microcirculation and aid wound healing (Wollina et al 2006). In vitro studies indicate that they have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and that they inhibit platelet aggregation and hyaluronidase, and reduce oedema, possibly by reducing capillary permeability. Preclinical in vivo experiments demonstrated anti-inflammatory and capillary wall thickening effects.

Antiplatelet and anti atherosclerotic drugs

Many items of diet also have antiplatelet effects, for example the flavonoids and anthocyanidins, as well as garlic, which is used as a food supplement for this and other purposes (e.g. as an antimicrobial). Garlic also has anti-atherosclerotic effects and is part of the ‘Mediterranean diet’ or the ‘French paradox’, in which there is a generally lower incidence of heart disease despite a cuisine rich in cream and butter. Other elements of this diet include olive oil, which contains monounsaturated fatty acids, which also lower blood cholesterol levels, and red wine, which contains anthocyanidins (see bilberry, above).

Ginkgo has antiplatelet activity and is used to improve peripheral blood circulation; this has a beneficial effect on memory and cognitive processes and will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 25. Generally these medicines are very safe, but care should be taken if they are used in conjunction with anticoagulants or prior to surgery. High-fibre phytomedicines, also used as bulk laxatives such as ispaghula and psyllium husk, lower plasma lipid levels and can be used as adjuncts to a low-fat diet. Oat bran (Avena sativa) and guar gum (Cyamopsis tetragonolobus; see also Chapter 19) lower cholesterol levels; these are thought to act by binding to cholesterol Weinmann et al 2010.

Garlic, Allium sativum L. (Allii sativi bulbus)

Constituents

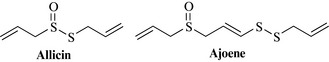

Garlic contains a large number of sulphur compounds which are responsible for the flavour and odour of garlic, as well as the medicinal effects. The main compound in the fresh plant is alliin, which on crushing undergoes enzymatic hydrolysis by alliinase to produce allicin (S-allyl-2-propenthiosulphinate; Fig. 15.5). This in turn forms a wide range of compounds such as allylmethyltrisulphide, diallyldisulphide, ajoene and others, many of which are volatile. Sulphur-containing peptides such as glutamyl-S-methylcysteine, glutamyl-S-methylcysteine sulphoxide and others are also present.

Therapeutic uses and available evidence

Different types of garlic preparations are available, such as standardized allicin-rich extracts, aged garlic extracts (particularly in the Far East) and capsules containing the oil (older products). All have different compositions, but it is recognized that the sulphur-containing compounds must be present for the therapeutic effect. Deodorized products, except for those containing the precursor allicin, are ineffective. Hypolipidaemic activity has been observed in animals with garlic extract; this has been attributed to S-allylcysteine which is regarded as important in this activity. S-Allylcysteine inhibits NF-kB synthesis and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation, which are both implicated in atherosclerosis. Allicin is also antioxidant, and garlic extracts protect endothelial cells from oxidized LDL damage. It is known that ajoene (Fig. 15.5) is a potent antithrombotic agent, as well as 2-vinyl-4H-1, 3-dithiin to a lesser extent. Cardiovascular benefits are supported by the antithrombotic activity, which has been shown in several studies, and an antiplatelet effect demonstrated by aged garlic extracts in humans.

Other health benefits attributed to garlic are antibacterial, antiviral and antifungal effects, and, more importantly, chemopreventative activity against carcinogenesis in various experimental models. Diallylsulphide is thought to inhibit carcinogen activation via cytochrome P450-mediated oxidative metabolism, and epidemiological evidence suggests that a diet rich in garlic reduces the incidence of cancer. Hepatoprotection against paracetamol (acetaminophen)-induced liver damage has been described and attributed to similar mechanisms. The evidence for the health benefits of taking garlic is generally good despite the poor quality of some trials (Aviello et al 2009). The usual dose of garlic products is equivalent to 600–900 mg of garlic powder daily. Garlic has few side effects, but due to the antiplatelet effects, care should be taken if given in combination with other cardiovascular drugs.

Altern. Med. Rev.. 2010;15;2:164-167. (Crataegus)

Aviello G., Abenavoli L., Borrelli F., et al. Garlic: empiricism or science? Natural Product Communications. 2009;4:1785-1796.

Bernatoniene J., Trumbeckaite S., Majiene D., et al. The effect of crataegus fruit extract and some of its flavonoids on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the heart. Phytother. Res.. 2009;23:1701-1707.

Canter P.H., Ernst E. Anthocyanosides of Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry) for night vision – a systematic review of placebo-controlled trials. Surv. Ophthalmol.. 2004;49:38-50.

Christie S., Walker A.F., Lewith G.T. Flavonoids – a new direction for the treatment of fluid retention? Phytother. Res.. 2001;15:467-475.

Felixsson E., Persson I.A., Eriksson A.C., Persson K. Horse chestnut extract contracts bovine vessels and affects human platelet aggregation through 5-HT(2A) receptors: an in vitro study. Phytother. Res.. 2010;24:1297-1301.

Hollmann A. Plants in Cardiology. London: BMJ Books; 1992.

Jayachandran K.S., Khan M., Selvendiran K., Devaraj S.N., Kuppusamy P. Crataegus oxycantha extract attenuates apoptotic incidence in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating Akt and HIF-1 signaling pathways. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol.. 2010;56:526-531.

Kalus U., Koscielny J., Grigorov A., Schaefer E., Peil H., Kiesewetter H. Improvement of cutaneous microcirculation and oxygen supply in patients with chronic venous insufficiency by orally administered extract of red vine leaves AS 195: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Drugs R D. 2004;5(2):63-71.

Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 25(1), 2006. Jan CD003230

Redman D.A. Ruscus aculeatus (butcher’s broom) as a potential treatment for orthostatic hypotension, with a case report. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2000;6:539.

Suter A., Bommer S., Rechner J. Treatment of patients with venous insufficiency with fresh plant horse chestnut seed extract: a review of 5 clinical studies. Adv. Ther.. 2006;23:179-190.

Swaminathan J.K., Khan M., Mohan I.K., et al. Cardioprotective properties of Crataegus oxycantha extract against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:744-752.

Walker A., Marakis G., Morris A.P., Robinson P.A. Promising hypotensive effect of hawthorn extract: a randomized double-blind pilot study of mild, essential hypertension. Phytother. Res.. 2002;16:48-54.

Weinmann S., Roll S., Schwarzbach C., Vauth C., Willich S.N. Effects of Ginkgo biloba in dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr.. 10(14), 2010.

Williamson E.M., Driver S., Baxter K. In: Stockley’s herb–drug interactions. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009.

Wollina U., Abdel-Naser M.B., Mani R. A review of the microcirculation in skin in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: the problem and the evidence available for therapeutic options. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds. 2006;5:169-180.

Wu B., Liu M., Zhang S. Dan Shen agents for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2, 2007. CD004295

Wu T., Ni J., Wu J. Danshen (Chinese medicinal herb) preparations for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2, 2008. CD004465

Yu S., Zhong B., Zheng M., Xiao F., Dong Z., Zhang H. The quality of randomized controlled trials on DanShen in the treatment of ischemic vascular disease. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2009;15:557-565.

Zick S.M., Zick S.M., Vautaw B.M., Gillespie B., Aaronson K.D. Hawthorn Extract Randomized Blinded Chronic Heart Failure (HERB CHF) trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail.. 2009;11:990-999.