Chapter 9 The Breast

A. Generalities

(1) Inspection

9 Which areas should be examined?

Breast tissue is contained in an imaginary pentagon, whose lateral border follows the midaxillary line, from the middle of the axilla down to the inframammary (or bra) line (fifth to sixth interspace); the lower border crosses along the inframammary fold toward the xiphoid process; the medial border ascends the midsternal line toward the suprasternal notch; and the upper border follows the clavicle before turning down toward the midaxilla. This pentagon can then be divided into four quadrants (Fig. 9-1). Most cancers originate in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, and also below the areola and nipple, two areas containing a large amount of glandular tissue. Always inspect first and palpate later.

11 Which bedside maneuver can help to detect breast abnormalities on inspection?

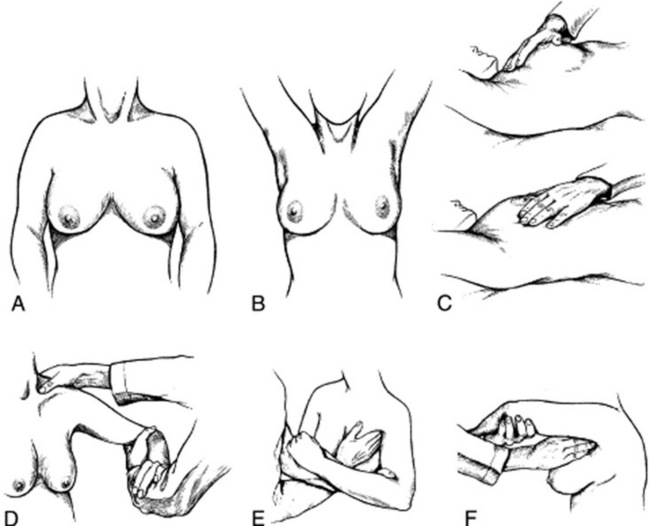

The most commonly taught and used maneuvers include a change in position of the patient’s arms and hands, first described by Haagensen (Fig. 9-2). To do so, ask the patient to carry out the following sequence:

1. >Rest the hands on the lap (to relax the pectoralis muscles).

2. Press them over the hips (to tense the pectoralis muscles and make dimpling and retraction more visible).

3. Raise them above the head, clasping them behind it (to also trigger skin dimpling, an important harbinger of cancer).

4. Lean forward (to allow the breasts to hang out pendulous from the chest).

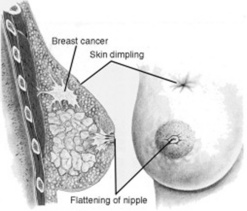

13 What is skin dimpling?

A slight depression or indentation in the breast’s surface (Fig. 9-3). This is an important clue to an underlying infiltrating carcinoma, causing fibrosis and retraction of the breast tissue. The same mechanism is responsible for nipple deviation.

21 What is meant by an adequate examination pattern?

Although two fifths of physicians may use no discernible pattern, proper technique is key for lesion detection. The two traditional methods are the radial spoke pattern and the concentric circles pattern (Fig. 9-4). However, the vertical strip pattern has been found to be more thorough. Begin your palpation in the axilla, and extend it in a straight line down the midaxillary line toward the bra line. Then move your fingers medially, continuing palpation up the chest, and in a straight line to the clavicle. Cover the entire breast, going up and down between the clavicle and bra line in a vertical strip pattern (or lawnmower technique). To cover all breast tissue, overlap rows.

22 Describe the correct finger position, movement, and pressure.

Making small circles, as if following the edge of a dime

Making small circles, as if following the edge of a dime

Making three circles at each spot, using three different pressures—light for superficial structures (skin and subcutaneous tissue), medium for the breast per se, and deep for the chest wall. This ensures that all levels of tissue are reached.

Making three circles at each spot, using three different pressures—light for superficial structures (skin and subcutaneous tissue), medium for the breast per se, and deep for the chest wall. This ensures that all levels of tissue are reached.

Examining each area carefully, all the way down to the thoracic wall. Pay attention to the tactile quality of skin, subcutaneous fat, and breast tissue

Examining each area carefully, all the way down to the thoracic wall. Pay attention to the tactile quality of skin, subcutaneous fat, and breast tissue

hen moving on to the next area, always using a consistent pattern

hen moving on to the next area, always using a consistent pattern

23 What are the final steps in the CBE?

Complete the exam by palpating for adenopathy in the supraclavicular and axillary fossae (Fig. 9-5). Then examine the nipple, through palpation and a squeeze. Although search for adenopathy is a routine component of the CBE, breast cancer is present in only 10–30% of women with isolated axillary lymphadenopathy and an otherwise normal CBE.

26 How should a breast lump (or nodule) be described?

Size: Assess it by using a ruler, tape measure, or, even better, plastic calipers. Remember that larger lumps (>2 cm) are more likely to be neoplastic.

Size: Assess it by using a ruler, tape measure, or, even better, plastic calipers. Remember that larger lumps (>2 cm) are more likely to be neoplastic.

Location: Describe it in relation to the breast’s four quadrants and the distance from the areolar rim. Report the finding by using the clock analogy.

Location: Describe it in relation to the breast’s four quadrants and the distance from the areolar rim. Report the finding by using the clock analogy.

Tenderness: Usually a sign of benignity

Tenderness: Usually a sign of benignity

Consistency or firmness: Rock-hard in cancers; soft, compressible, and at times even cystic in benign lesions

Consistency or firmness: Rock-hard in cancers; soft, compressible, and at times even cystic in benign lesions

Shape: This should include an assessment of regularity/irregularity and contour. Lesions with indistinct and irregular margins are more likely to be malignant.

Shape: This should include an assessment of regularity/irregularity and contour. Lesions with indistinct and irregular margins are more likely to be malignant.

Relation to surrounding tissue: Use Haagensen’s maneuvers to evaluate mobility over superficial and deep planes. Fixed lesions are more likely to be malignant.

Relation to surrounding tissue: Use Haagensen’s maneuvers to evaluate mobility over superficial and deep planes. Fixed lesions are more likely to be malignant.

Character of the overlying skin: Look for warmth, redness, swelling, or retraction.

Character of the overlying skin: Look for warmth, redness, swelling, or retraction.

27 What are the characteristics of malignant breast tissue?

A carcinomatous lesion is typically painless, irregular in contour and shape, hard in consistency, not mobile, and not well demarcated from the surrounding tissues. Retraction signs are usually a late phenomenon. A serous (or serosanguineous) nipple discharge can be an important sign of intraductal carcinomas (see questions 37–40).

32 What are the most common benign breast lesions?

Fibroadenomas: The most common benign neoplasms. They present as solitary, well-demarcated, rubbery, mobile, nontender masses, often round, but also ovoid or oblong. May occur at any time after puberty, but less frequently after menopause.

Fibroadenomas: The most common benign neoplasms. They present as solitary, well-demarcated, rubbery, mobile, nontender masses, often round, but also ovoid or oblong. May occur at any time after puberty, but less frequently after menopause.

Benign cysts: The most common breast lumps. Since they are often part of a fibrocystic pattern, they tend to coexist with other cysts. They are round, mobile, soft, and cystic in feel. They vary with the menstrual cycle, becoming tender before menses, and smaller immediately after (hence, to avoid misdiagnosis do a breast exam only in this phase of the menstrual cycle). They regress after menopause.

Benign cysts: The most common breast lumps. Since they are often part of a fibrocystic pattern, they tend to coexist with other cysts. They are round, mobile, soft, and cystic in feel. They vary with the menstrual cycle, becoming tender before menses, and smaller immediately after (hence, to avoid misdiagnosis do a breast exam only in this phase of the menstrual cycle). They regress after menopause.

34 What is the differential diagnosis of an inflammatory breast mass?

It depends on whether it is diffuse or localized:

Diffuse inflammatory breast masses include acute mastitis and inflammatory breast carcinoma.

Diffuse inflammatory breast masses include acute mastitis and inflammatory breast carcinoma.

Localized inflammatory masses are instead the result of an acute breast abscess—a well-localized, tender, swollen, erythematous, and often fluctuant lesion. Patients usually present with systemic signs and symptoms of infection (like fever, malaise, and leukocytosis), usually in a setting of lactation, since abscesses are often the end result of an acute mastitis.

Localized inflammatory masses are instead the result of an acute breast abscess—a well-localized, tender, swollen, erythematous, and often fluctuant lesion. Patients usually present with systemic signs and symptoms of infection (like fever, malaise, and leukocytosis), usually in a setting of lactation, since abscesses are often the end result of an acute mastitis.

35 How can one separate acute mastitis from inflammatory breast carcinoma?

Both conditions present with diffuse and tender masses:

Acute mastitis is a glandular infection that involves only a single breast quadrant, usually during lactation. The affected area is red, swollen, tender, and associated with systemic signs of infection (fever, malaise, elevated white blood cell count).

Acute mastitis is a glandular infection that involves only a single breast quadrant, usually during lactation. The affected area is red, swollen, tender, and associated with systemic signs of infection (fever, malaise, elevated white blood cell count).

Inflammatory breast carcinoma involves instead the entire breast and is typically associated with axillary adenopathy (usually absent in acute mastitis). Lack of association with lactation and lack of response to antibiotics should raise the suspicion for neoplasm and prompt a biopsy.

Inflammatory breast carcinoma involves instead the entire breast and is typically associated with axillary adenopathy (usually absent in acute mastitis). Lack of association with lactation and lack of response to antibiotics should raise the suspicion for neoplasm and prompt a biopsy.

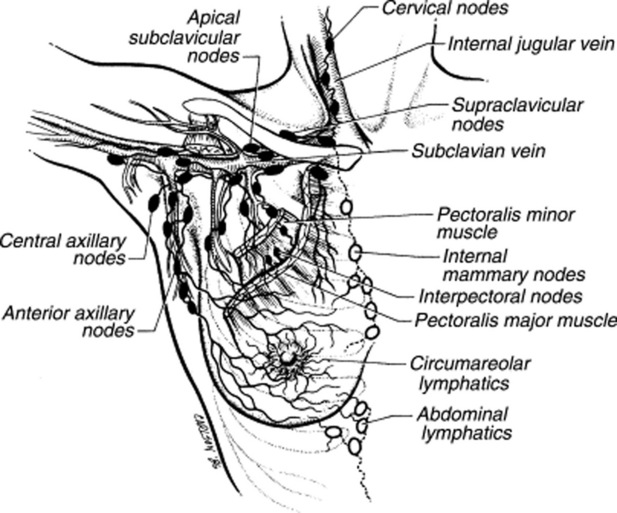

36 Describe the lymphatic drainage of the breasts.

The superficial and central areas are drained by lymphatics that radiate from the areola and then converge toward the low/central axillary nodes and the subclavian nodes.

The superficial and central areas are drained by lymphatics that radiate from the areola and then converge toward the low/central axillary nodes and the subclavian nodes.

The deep tissue is drained instead by pectoral, subclavian, and internal mammary nodes. These eventually drain into mediastinal stations.

The deep tissue is drained instead by pectoral, subclavian, and internal mammary nodes. These eventually drain into mediastinal stations.

Finally, other breast lymphatics drain into hepatic and subdiaphragmatic nodes (Fig. 9-6).

Finally, other breast lymphatics drain into hepatic and subdiaphragmatic nodes (Fig. 9-6).

B. Nipple Discharge

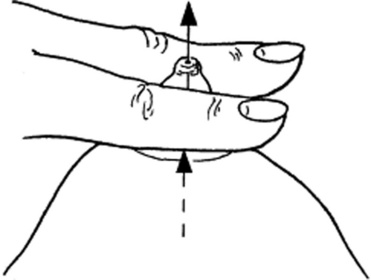

37 How do you assess for nipple discharge?

By applying gentle pressure at the base of the nipple, with the thumb and first or second finger (Fig. 9-7). Note that a discharge that occurs only with nipple compression/squeezing is usually physiologic. In a study of 448 women complaining of discharge, none of the 178 who had it only after expression was found to have cancer. Conversely, cancer was present in 2% (3/151) of those with spontaneous discharge but otherwise normal CBE.

C. Breast Self Examination (BSE)

1 Atkins H, Wolff B. Discharges from the nipple. Br J Surg. 1964;51:602-606.

2 Baines CJ, Wall C, Risch HA, et al. Changes in breast self-examination behaviour in a cohort of 8214 women in the Canadian National Breast Screening study. Cancer. 1986;57:1209-1216.

3 Barton MB, Harris R, Fletcher SW. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have breast cancer? JAMA. 1999;282:1270-1280.

4 Boyd NF, Sutherland HJ, Fish EB, et al. Physical examination of the breast. Am J Surg. 1981;142:307-426.

5 Chaudary MA, Millis RR, Davies GC, Hayward JL. Nipple discharge: The diagnostic value of testing for occult blood. Ann Surg. 1982;196:651-655.

6 De Gowin RL. Diagnostic Examination, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

7 Egan RL, Goldstein GT, McSweeney MM, et al. Conventional mammography, physical examination, thermography, and xeroradiography in the detection of breast cancer. Cancer. 1997;39:1984-1992.

8 Fletcher SW, O’Malley MS, Bumce LA. Physicians’ abilities to detect lumps in silicone breast models. JAMA. 1985;253:2224-2228.

9 Gump FE. Sensitivity and specificity in silicone breast models. JAMA. 1985;254:2409.

10 Hicks MJ, Davis JR, Layton JM, Present AJ. Sensitivity of mammography and physical examination of the breast for detecting breast cancer. JAMA. 1979;242:2080-2083.

11 Mushlin AI. Diagnostic tests in breast cancer. Clinical strategies based on diagnostic probabilities. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:79-85.

12 Newman HF, Klein M, Northrup JD, et al. Nipple discharge: Frequency and pathogenesis in an ambulatory population. N Y State J Med. 1983;83:928-933.

13 Nydick M, Bustos J, Dale JHJr, et al. Gynecomastia in adolescent boys. JAMA. 1961;178:449-454.

14 O’Malley MS, Fletcher SW. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer with breast self-examination. A critical review. JAMA. 1987;257:2196-2203.