Chapter 20 The Bedside Diagnosis of Coma

-René Theophyle Yacinthe Laennec, 1810; letter to his cousin Cristophe

“His was a great sin who first invented consciousness. Let us lose it for a few hours.”

-John, in The Diamond as Big as the Ritz, by F. Scott Fitzgerald—uttered before falling asleep

Generalities

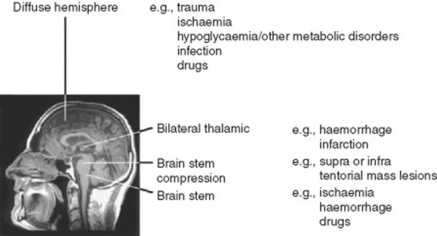

15 So what are the causes of coma?

Diffuse or extensive processes affecting the whole brain (but primarily the cortex)

Diffuse or extensive processes affecting the whole brain (but primarily the cortex)

Brain stem lesions—including not only primary disorders of the brain stem (such as hemorrhages, infarction, and cancer), but also compression from mass lesions of the posterior fossa (such as cerebellar hemorrhage/infarction)

Brain stem lesions—including not only primary disorders of the brain stem (such as hemorrhages, infarction, and cancer), but also compression from mass lesions of the posterior fossa (such as cerebellar hemorrhage/infarction)

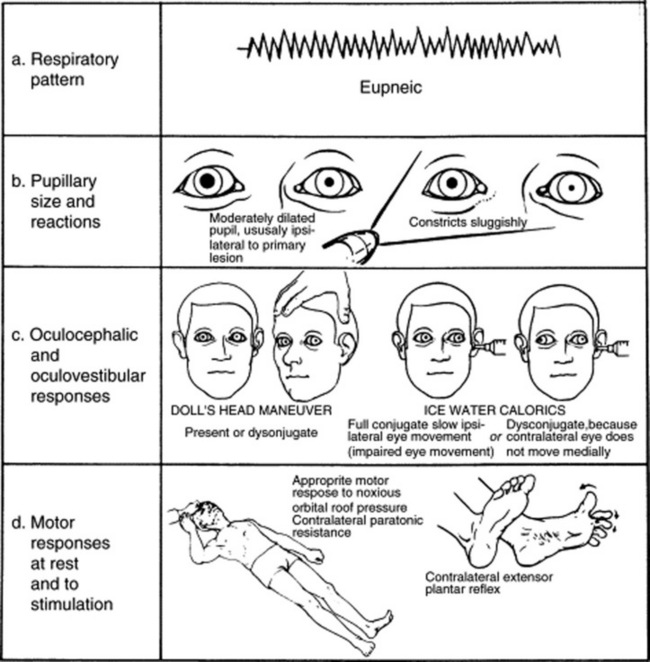

Supratentorial mass lesions causing transtentorial herniation with brain stem compression (these are often associated with other neurologic signs, such as third nerve palsy and crossed hemiparesis) (see Fig. 20-1)

Supratentorial mass lesions causing transtentorial herniation with brain stem compression (these are often associated with other neurologic signs, such as third nerve palsy and crossed hemiparesis) (see Fig. 20-1)

In a large study of “medical comas,” 50% of all cases were cerebrovascular in nature, 20% due to hypoxic/ischemic injury, and the rest is a miscellanea of metabolic/infective encephalopathies.

In a large study of “medical comas,” 50% of all cases were cerebrovascular in nature, 20% due to hypoxic/ischemic injury, and the rest is a miscellanea of metabolic/infective encephalopathies.

16 What is the function of the neurologic exam in comatose patients?

Coma without focal signs or meningism: The most common; due to dysmetabolic states of the entire CNS: anoxic/ischemic, toxic, drug-induced, infectious, postictal.

Coma without focal signs or meningism: The most common; due to dysmetabolic states of the entire CNS: anoxic/ischemic, toxic, drug-induced, infectious, postictal.

Coma without focal signs but with meningism: Due to subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, and meningoencephalitis

Coma without focal signs but with meningism: Due to subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, and meningoencephalitis

Coma with focal signs: Due to intracranial hemorrhage, infarction, tumor, or abscess

Coma with focal signs: Due to intracranial hemorrhage, infarction, tumor, or abscess

17 What is the neurologic exam of a comatose patient?

A simple one. Since the cortex of coma is, by definition, dysfunctional, exam is only aimed at assessing brain stem function. This is carried out in a rostral-caudal and level-by-level fashion. If all four layers of the brain stem are working properly, then the coma is cortical (i.e., one in which the cortex is primarily dysfunctional). If one or more brain stem layer is damaged, then the coma is a brain stem coma (i.e., one in which the cortex is secondarily dysfunctional as a result of direct brain stem damage) (see Table 20-1).

| General Examination |

Skin (e.g., rash, anemia, cyanosis, jaundice) Skin (e.g., rash, anemia, cyanosis, jaundice) |

Temperature (fever-infection, hypothermia-drugs, circulatory failure) Temperature (fever-infection, hypothermia-drugs, circulatory failure) |

Blood pressure (e.g., septicemia, Addison’s disease) Blood pressure (e.g., septicemia, Addison’s disease) |

Breath (e.g., fetor hepaticus) Breath (e.g., fetor hepaticus) |

Cardiovascular (e.g., arrhythmias) Cardiovascular (e.g., arrhythmias) |

Abdomen (e.g., organomegaly) Abdomen (e.g., organomegaly) |

| Neurologic Examination |

Head, neck, and eardrum (trauma) Head, neck, and eardrum (trauma) |

Meningism (subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis) Meningism (subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis) |

Funduscopy Funduscopy |

| Level of Consciousness |

Glasgow Coma Scale (verbal response, eye opening, motor response) Glasgow Coma Scale (verbal response, eye opening, motor response) |

| Brain Stem Function |

Pupillary responses Pupillary responses |

Spontaneous eye movements Spontaneous eye movements |

Oculocephalic responses Oculocephalic responses |

Caloric responses Caloric responses |

Corneal responses Corneal responses |

| Motor Function |

Motor response Motor response |

Deep tendon reflexes Deep tendon reflexes |

Muscle tone Muscle tone |

Plantars Plantars |

| Respiratory Pattern |

Cheyne-Stokes: hemisphere Cheyne-Stokes: hemisphere |

Central neurogenic hyperventilation: rapid/midbrain Central neurogenic hyperventilation: rapid/midbrain |

Apneustic: rapid with pauses/lower pontine Apneustic: rapid with pauses/lower pontine |

(Adapted from Bateman DE. Neurological assessment of coma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 71[Suppl 1]: i13–i17, 2001.)

19 What is the first step in evaluating coma?

To assess whether there is any response to verbal stimuli. This can be done by asking patients to open their eyes and look up, down, and from side to side. “Locked-in” patients (see question 54) will open their eyes on command, and even look up and down, but will be unable to make any other purposeful response. Once this is done, the next step in the evaluation of coma is to test the first and uppermost brain stem level: the thalamus.

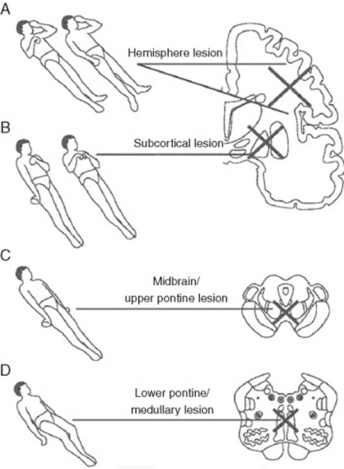

22 What are these postures?

Valuable findings for localization. A decorticate posture is a sign of subcortical/thalamic dysfunction. It consists of upper extremities’ flexion, with extension and internal rotation of lower extremities. A decerebrate posture consists instead of extension and internal rotation of both upper and lower extremities. This is a sign of upper brain stem dysfunction, usually the consequence of midbrain or upper pontine lesions. Finally, lower brain stem damage (low pontine and medullary) will cause no response to painful stimuli, or just extension of the upper extremities with simple bending of the knees (a spinal reflex). Unilateral decerebrate or decorticate responses also may occur, usually indicating unilateral lesions. Overall, it is easy to separate decortication from decerebration by remembering that in de-cor-tication the hand points toward the heart (cor), whereas in decerebration the hand points away from the heart (see Fig. 20-2).

26 What is the significance of pupillary abnormalities?

Paralysis of the pupil (i.e., inability to constrict in response to light) indicates an ipsilateral dysfunction of the midbrain (midbrain pupils = midposition or slightly widened and fixed pupils unreactive to light). Pontine pupils are instead bilateral small pupils that still react to light, even though this may only be visible under a magnifying glass. They reflect anatomic lesions in the tegmentum. Pinpoint pupils are both small and constricted but reactive; they often occur in metabolic encephalopathy and may be due to opiates. Bilaterally dilated pupils are instead encountered in patients with atropine and scopolamine toxicity (see Fig. 20-3). Note the following: (1) drugs that are frequently used in resuscitation from cardiac arrest (such as atropine or dopamine) may have misleading effects on pupillary reactions, (2) lesions above the thalamus and below the pons usually preserve pupillary reactions, and (3) finally, a third nerve lesion can be differentiated from a contralateral Horner’s by the position of the eye and the degree of ptosis.

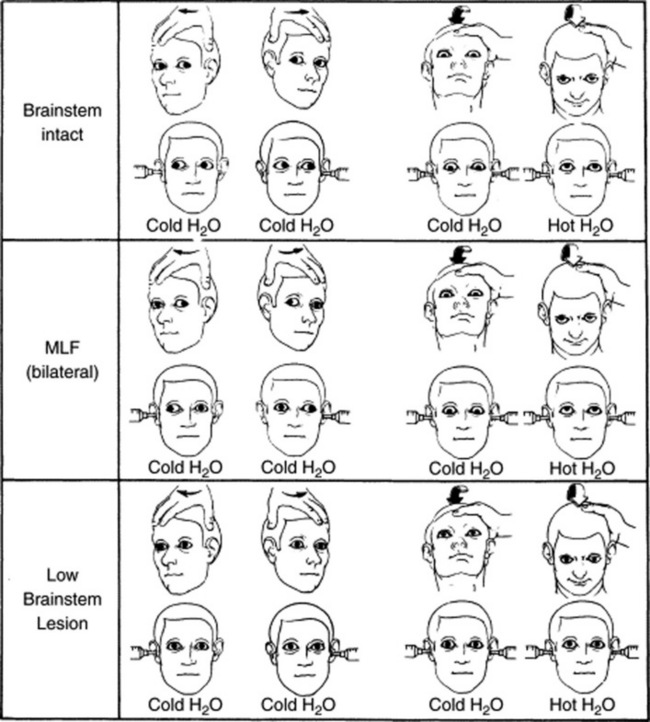

32 What is the pathway of the oculocephalic reflex?

The stimulus is either mechanical (rotation of the patient’s head along the horizontal plane) or thermic (injection of a syringe full of liquid in the external ear canal).

The stimulus is either mechanical (rotation of the patient’s head along the horizontal plane) or thermic (injection of a syringe full of liquid in the external ear canal).

The receptors are in the inner ear (semicircular canals and utriculus).

The receptors are in the inner ear (semicircular canals and utriculus).

Once these receptors are activated, the afferent signal is carried to the central nervous system via the eighth cranial nerve. This enters the brain stem at the cerebellar–pontine angle.

Once these receptors are activated, the afferent signal is carried to the central nervous system via the eighth cranial nerve. This enters the brain stem at the cerebellar–pontine angle.

The impulse is then taken to the ocular muscles by the efferent pathway (third and sixth cranial nerves), eliciting eye movement across the horizontal plane. Since the third nerve resides in the midbrain and the sixth in the upper pons, the electrical impulse will need a “connecting wire” to travel from the lower pons to the upper pons and midbrain. This wire is the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF).

The impulse is then taken to the ocular muscles by the efferent pathway (third and sixth cranial nerves), eliciting eye movement across the horizontal plane. Since the third nerve resides in the midbrain and the sixth in the upper pons, the electrical impulse will need a “connecting wire” to travel from the lower pons to the upper pons and midbrain. This wire is the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF).

38 What is the implication of a global absence of brain stem function?

It indicates death (see question 53). Given its implications, a repeat neurologic exam is usually required at a 12-hour interval. Also, toxic-metabolic states need to be excluded.

41 What are the causes of a toxic-metabolic coma?

They are exogenous or endogenous toxins, affecting the cortex bilaterally and diffusely.

Exogenous toxins are poisons. Hence, a toxic screen should always be carried out.

Exogenous toxins are poisons. Hence, a toxic screen should always be carried out.

Endogenous toxins are also poisons that accumulate when there is dysfunction of major detoxifying parenchyma (hepatic, renal, or hypercapnic encephalopathy).

Endogenous toxins are also poisons that accumulate when there is dysfunction of major detoxifying parenchyma (hepatic, renal, or hypercapnic encephalopathy).

Endocrinopathies: These include hypothyroidism (myxedema coma) and global dysfunction of the hypophysis (panhypopituitarism) or adrenals (Addisonian crisis). In addition, defects in glucose metabolism, either in excess (diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar nonketotic coma) or in deficiency (hypoglycemic encephalopathy), also may cause coma. Finally, electrolyte disturbances (hyponatremia and hypernatremia, hypercalcemia, and hypermagnesemia), can do it, too.

Endocrinopathies: These include hypothyroidism (myxedema coma) and global dysfunction of the hypophysis (panhypopituitarism) or adrenals (Addisonian crisis). In addition, defects in glucose metabolism, either in excess (diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar nonketotic coma) or in deficiency (hypoglycemic encephalopathy), also may cause coma. Finally, electrolyte disturbances (hyponatremia and hypernatremia, hypercalcemia, and hypermagnesemia), can do it, too.

Subarachnoid toxins: Direct, generalized poisoning of the cerebral cortex by toxins spreading along the subarachnoid space is another cause of toxic-metabolic coma. The most common culprit is blood (subarachnoid hemorrhage) or pus (purulent meningitis). Both can be detected by lumbar puncture. Hence, this should be part of the standard work-up of all comatose patients, especially those with meningeal signs.

Subarachnoid toxins: Direct, generalized poisoning of the cerebral cortex by toxins spreading along the subarachnoid space is another cause of toxic-metabolic coma. The most common culprit is blood (subarachnoid hemorrhage) or pus (purulent meningitis). Both can be detected by lumbar puncture. Hence, this should be part of the standard work-up of all comatose patients, especially those with meningeal signs.

A generalized electrical disturbance (such as a seizure) also may lead to coma. This can occur during or after the crisis (postictal coma). Since subclinical seizures may lack classic tonicoclonic contractions (i.e., patients can be immobile or just exhibit a fine fluttering of the eyelids), all coma patients should undergo electroencephalographic (EEG) testing.

A generalized electrical disturbance (such as a seizure) also may lead to coma. This can occur during or after the crisis (postictal coma). Since subclinical seizures may lack classic tonicoclonic contractions (i.e., patients can be immobile or just exhibit a fine fluttering of the eyelids), all coma patients should undergo electroencephalographic (EEG) testing.

Finally, a common cause of metabolic coma is hypoxic encephalopathy (HE), a term that is probably incorrect, since the bilateral cortical dysfunction of these patients might be due more to reperfusion injury than true hypoxia. HE affects primarily the cortex, while the brain stem remains mostly intact. Thus, after going through the initial state of coma (i.e., sleep-like), HE patients eventually emerge into persistent vegetative state, insofar as their brain stem sends impulses to the cortex (arousal) but the cortex is unable to process them. Hence, the original term of “apallic syndrome” (i.e., one characterized by destruction of the pallium, the telencephalon-covering gray matter).

Finally, a common cause of metabolic coma is hypoxic encephalopathy (HE), a term that is probably incorrect, since the bilateral cortical dysfunction of these patients might be due more to reperfusion injury than true hypoxia. HE affects primarily the cortex, while the brain stem remains mostly intact. Thus, after going through the initial state of coma (i.e., sleep-like), HE patients eventually emerge into persistent vegetative state, insofar as their brain stem sends impulses to the cortex (arousal) but the cortex is unable to process them. Hence, the original term of “apallic syndrome” (i.e., one characterized by destruction of the pallium, the telencephalon-covering gray matter).

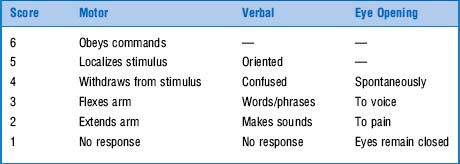

44 What is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)?

It is an important tool for evaluating coma, first introduced by Teasdale and Jennett in 1974. Prior to it, coma assessment was exclusively based on presence/absence of various brain stem reflexes (previously discussed). The GCS has instead provided a standardized way of classifying the condition, and as such has become an international standard. It consists of an ordinal scale calculated from the sum of three components: motor response, verbal response, and eye opening. Scores range from 3–15 (Table 20-2). Although originally described for traumatic coma, the GCS is equally applicable to nontraumatic coma. Still, even though it does predict poor neurologic outcome, it is not as predictive as the individual motor and brain stem reflex components (see questions 45 and 46). Moreover, assessing motor response requires that you apply central pain because peripheral stimulation may cause misleading spinal reflexes that do not represent a true motor response. Hence, to give a proper painful stimulus you need to pinch the skin of the supraorbital region or the sternum (using, for example, your knuckles to apply a firm twisting pressure).

49 What is the bottom line for the neurologic exam of coma?

It is a valuable tool, with moderate to substantial precision and good prognostic value.

50 What is asterixis?

From the Greek a (lack of) and sterixis (fixed position), this is the bilateral flapping tremor of metabolic encephalopathy, particularly impending hepatic coma (see Chapter 15, question 79). It was first described in 1949 by Foley and Adams. Foley, a notorious wit, coined the term while drinking at a Greek bar across from Boston City Hospital. He then used it semiseriously in a paper, not expecting much of it. To his amazement, the word became the official academic term for flapping tremor due to the inability of maintaining a voluntary muscular contraction (asterixis requires patient cooperation and thus cannot be elicited in stupor or coma). It consists of involuntary jerking movements, in a typical sequence of flexions and extensions. Since it reflects a lapse of posture, it involves antigravitary muscles, such as those of wrist, metacarpophalangeal, and hip joints, but also toes, eyelids, and even tongue. Still, it is typically assessed in the hands.

54 What conditions may look like coma but are not coma?

Locked-in state: Due to a discrete brain stem lesion, usually involving the junction between the upper and lower two thirds of the pons. Given its high location, there is enough pontine reticularis to preserve consciousness, even though all functions below the lesion are lost. Thus, locked-in patients can only control the high cranial nerves (III and VI), which means that they can move their eyes (and keep them open) but not their extremities. They also can see and hear the examiner but sense neither touch nor pain. Whereas in true coma (“sleep-like” state) the eyes are closed, in the locked-in state they are open—in fact, often tracking the examiner (when this happens, instruct the patient, “If you hear me, blink your eyes”). A locked-in state is usually fatal, bringing a merciful death in a matter of days. Yet there have been a few unfortunate souls who have lived trapped in their bodies for months and even years. A famous case involved Jean-Dominique Bauby, a 43-year-old French editor, who became locked-in as a result of a massive stroke. He eventually learned to communicate by blinking his eyes in front of an alphabet chart and even wrote a book about his experience (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly), published 2 months after his death.

Locked-in state: Due to a discrete brain stem lesion, usually involving the junction between the upper and lower two thirds of the pons. Given its high location, there is enough pontine reticularis to preserve consciousness, even though all functions below the lesion are lost. Thus, locked-in patients can only control the high cranial nerves (III and VI), which means that they can move their eyes (and keep them open) but not their extremities. They also can see and hear the examiner but sense neither touch nor pain. Whereas in true coma (“sleep-like” state) the eyes are closed, in the locked-in state they are open—in fact, often tracking the examiner (when this happens, instruct the patient, “If you hear me, blink your eyes”). A locked-in state is usually fatal, bringing a merciful death in a matter of days. Yet there have been a few unfortunate souls who have lived trapped in their bodies for months and even years. A famous case involved Jean-Dominique Bauby, a 43-year-old French editor, who became locked-in as a result of a massive stroke. He eventually learned to communicate by blinking his eyes in front of an alphabet chart and even wrote a book about his experience (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly), published 2 months after his death.

Hysteric coma: This is a coma-like state that results from major psychopathology. According to medical lore, it may be identified by raising the patient’s hand above his or her face and letting it drop. In contrast to real comatose patients, hysterics will not allow the hand to strike them, but will instead allow it to slowly fall down on the side. Similarly, they might resist the examiner’s attempt to open their eyelids.

Hysteric coma: This is a coma-like state that results from major psychopathology. According to medical lore, it may be identified by raising the patient’s hand above his or her face and letting it drop. In contrast to real comatose patients, hysterics will not allow the hand to strike them, but will instead allow it to slowly fall down on the side. Similarly, they might resist the examiner’s attempt to open their eyelids.

Catatonic coma (from the Greek katatonas, depressed): Patients often have a history of preexisting depression and develop catatonia after a major intercurrent illness. The eyes are open, and patients are awake, but immobile. Catatonia can resolve with benzodiazepines or short-acting barbiturates (like amytal).

Catatonic coma (from the Greek katatonas, depressed): Patients often have a history of preexisting depression and develop catatonia after a major intercurrent illness. The eyes are open, and patients are awake, but immobile. Catatonia can resolve with benzodiazepines or short-acting barbiturates (like amytal).

55 What is uncal herniation?

It is a rostral-caudal herniation of the uncus of the temporal lobe, with secondary compression of the brain stem. This causes patients to lose function layer by layer: first the thalamus, then the midbrain and pons, and finally the medulla. Neurologically, there is initial ipsilateral cerebral posturing (decortication and then decerebration), followed by lack of response to painful stimuli, ipsilateral pupillary paralysis, and loss of oculocephalic reflex. Finally, medullary compression and respiratory arrest occur (see Fig. 20-4).

1 Andrews K. Recovery of patients after four months or more in the persistent vegetative state. BMJ. 1993;306:1597-1600.

2 Bassetti C, Bomio F, Mathis J, Hess CW. Early prognosis in coma after cardiac arrest: A prospective clinical, electrophysiological, and biochemical study of 60 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61:610-615.

3 Bateman DE. Neurological assessment of coma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(Suppl 1):i3-i7.

4 Becker LR, Ostrander MP, Barrett J, Kondos GT. Outcome of CPR in a large metropolitan area. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:355-361.

5 Booth CM, Boone RH, Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Is this patient dead, vegetative, or severely neurologically impaired? Assessing outcome for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2004;291:870-879.

6 Dougherty JHJr, Rawlinson DG, Levy DE, Plum F. Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and the vegetative state: Clinical and neuropathologic correlation. Neurology. 1981;31:991-997.

7 Edgren E, Hedstrand U, Kelsey S, et al. Assessment of neurological prognosis in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. Lancet. 1994;343:1055-1059.

8 Hawkes CH. Diagnosis of functional neurological disease. Br J Hosp Med. 1997;57:373-377.

9 Krumholz A, Stern BJ, Weiss HD. Outcome from coma after cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Relation to seizures and myoclonus. Neurology. 1988;38:401-405.

10 Plum F, Posner JB. The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1972.

11 Sacco RL, VanGool R, Mohr JP, Hauser WA. Nontraumatic coma: Glasgow Coma Score and coma etiology as predictors of 2-week outcome. Arch Neurol. 1990;47:1181-1184.

12 Snyder BD, Gumnit RJ, Leppik IE, et al. Neurologic prognosis after cardiopulmonary arrest, IV: Brainstem reflexes. Neurology. 1981;31:1092-1097.

13 Snyder BD, Hauser A, Loewenson RB, et al. Neurologic prognosis after cardiopulmonary arrest, III: Seizure activity. Neurology. 1980;30:1292-1297.

14 Snyder BD, Loewenson RB, Gumnit RJ, et al. Neurologic prognosis after cardiopulmonary arrest, II: Level of consciousness. Neurology. 1980;30:52-58.

15 Snyder BD, Ramirez-Lassepas M, Lippert DM. Neurologic status and prognosis after cardiopulmonary arrest. I: A retrospective study. Neurology. 1977;27:807-811.

16 Steen-Hansen JE, Hansen NN, Vaagenes P, Schreiner B. Pupil size and light reactivity during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A clinical study. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:69-70.

17 Truog RD, Robinson WM. Role of brain death and the dead-donor rule in the ethics of organ transplantation. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2391-2396.