Chapter 8 The Back

Back pain is one of the most frequent conditions requiring medical treatment. It is also the most expensive ailment for patients between the ages of 30 and 60 years and one of the most difficult to treat. Back pain may be caused by a variety of disorders, including gynecologic, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal diseases, but the most common causes are disorders of the lumbar disc.

Anatomy

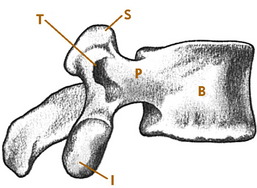

The vertebrae, discs, and ligaments of the dorsal and lumbar spine are similar in most respects to their counterparts in the cervical spine. The lumbar vertebrae are larger and thicker, however, because of their weight-bearing function (Fig. 8-1). Anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments are applied to the respective surfaces of the vertebral bodies, and posterior stability is aided by supraspinous and interspinous ligaments and the ligamentum flavum. The discs account for more than one third of the total height of the lumbar spine and account for most of the normal lordosis.

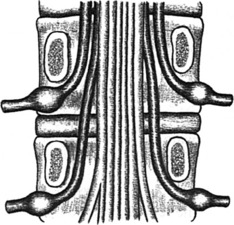

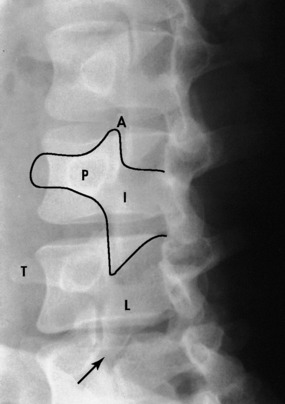

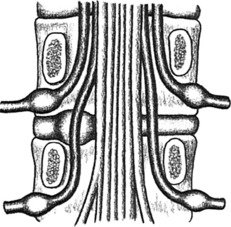

Spinal nerves exit the canal by passing through intervertebral foramina; each foramen consists of the inferior aspect of the pedicle above and the superior aspect of the pedicle below the level of exit. In the lumbar spine, disc disease usually affects the nerve root exiting one level below, because that is the nerve that actually passes over the disc (Fig. 8-2). Thus, a herniated disc between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae commonly affects the fifth nerve root and not the fourth.

History

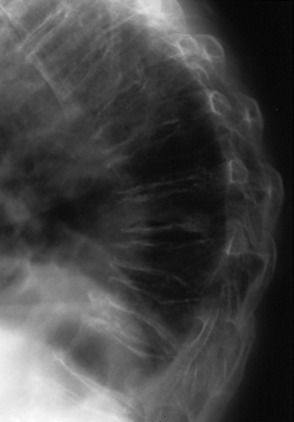

The evaluation of the patient with back pain should first begin with the obvious questions regarding the common causes of spine disorders (trauma, disc disease, degenerative disorders, etc.). However, because low back discomfort can develop in conjunction with a variety of diseases not considered orthopedic in nature, this initial assessment should also include information developed about general medical disorders that could be causally connected with the spine complaints. This is especially true if the symptoms appear atypical (pain radiating into the groin, testicle, vulva, or inner thigh). If this cannot be done on the initial visit because of limited time, it eventually must be done if the patient’s condition does not improve and the patient returns with the same complaints.

A few simple questions should be sufficient for general system review as follow:

The smoking history is always critical. In addition, certain “red flags” should signal the possibility of a more serious condition underlying the low back complaints (Table 8-1).

| Fever, malaise |

| History of malignancy |

| Night pain or pain at rest (suggests spinal malignancy) |

| Incontinence, perianal sensory loss |

| Weight loss of unknown origin |

| Loss of strength, balance |

| Sudden worsening of pain level |

| History of substance abuse or issues of secondary gain |

| Night sweats |

| Significant morning stiffness |

Examination

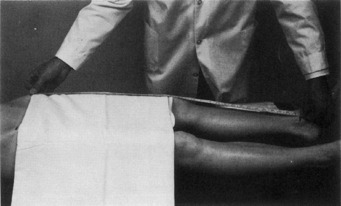

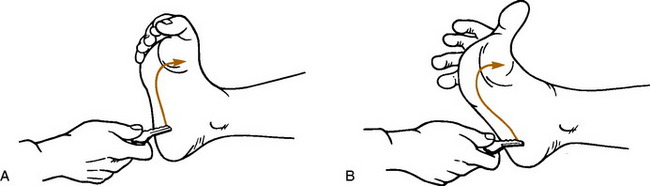

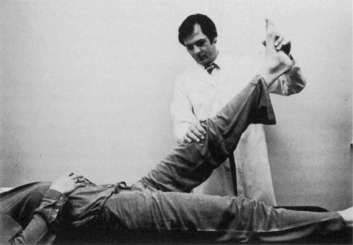

With the patient in the supine position, the hip is placed through a full range of motion and thoroughly tested to rule out primary hip abnormality. The straight-leg–raising tests are then performed, and the leg lengths are measured (Fig. 8-3). Next, with the patient on the side, manual pressure is applied to the iliac crest (pelvic compression test). Reproduction of pain in the sacroiliac joints or symphysis pubis with this maneuver may suggest disorders of these areas. The presence or absence of clonus can be determined at this time, and Babinski testing can be performed (Fig. 8-4).

Roentgenographic Anatomy

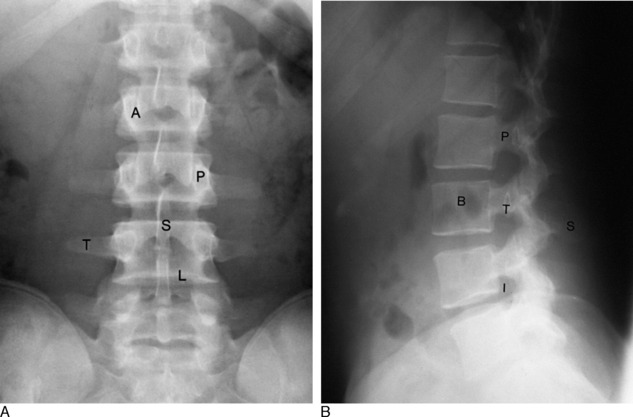

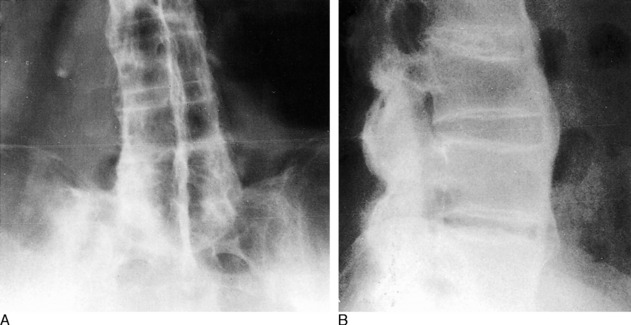

An evaluation of disorders of the lumbar spine should include a standard roentgenographic examination. The roentgenographic features are well visualized by the following: anteroposterior view (Fig. 8-5, A), lateral view (Fig. 8-5, B), and oblique views in both directions (Fig. 8-6). In addition, a spot lateral view of the lumbosacral space may be necessary.

Lumbar Disc Syndromes

The intervertebral disc is probably the major source of most back pain, and the pattern of disc deterioration in the lumbar spine is similar to what occurs in the cervical spine. The majority (95%) of disc lesions in the lumbar spine occur at the fourth and fifth spaces, with most of the remainder occurring at the third space. With normal aging, biochemical and mechanical changes occur in the nucleus pulposus. Eventually, disc material may begin to protrude or even herniate into the neural canal. This most often occurs in the area of greatest weakness of the anulus fibrosus at the posterolateral aspect of the disc (Fig. 8-7). Herniation is most common in the third and fourth decades and is rare before the age of 15. Chronic disc deterioration (spondylosis) may also develop over time and result in osteophyte formation, disc space narrowing, and degenerative changes in the facet joints and between adjacent vertebral bodies. (NOTE: In addition to mechanical causes, chemical and inflammatory factors may also play some role in the development of back pain. Although the mechanical causes may be the easiest to visually understand, a precise diagnosis as to the etiology of back pain in many patients simply cannot be established with any certainty.)

FIG. 8-7 Lumbar disc protrusion. Note that the herniation affects the root that exits one level below.

A rare but serious complication of lumbar disc disease is the cauda equina syndrome. This results from a massive central disc herniation and may produce variable degrees of permanent paralysis in the lower extremities. Bladder and bowel function may also be severely impaired. This condition is a true emergency and usually demands immediate evaluation and surgery.

CLINICAL FEATURES

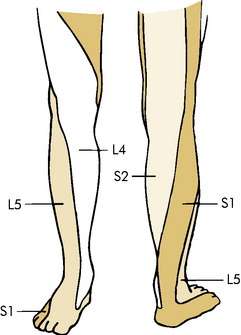

Paresthesias in the form of numbness and tingling are common and are usually more marked in the distal portion of the extremity. They may follow a specific dermatome pattern (Fig. 8-8).

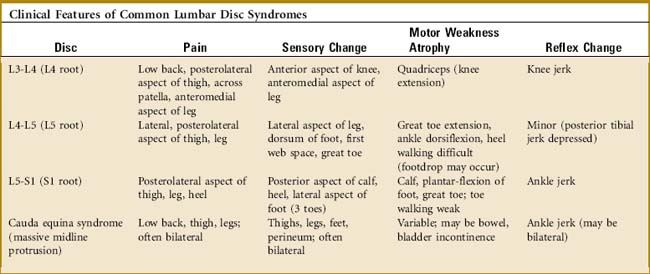

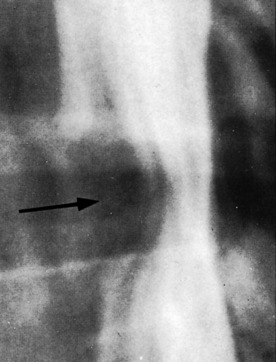

Examination often reveals restriction of low back motion. Bending toward the affected side frequently exacerbates the pain. Variable degrees of local tenderness and muscle guarding are present. In an attempt to relieve pressure or tension on the nerve root, the patient may list or bend away from the painful side and stand with the affected hip and knee slightly flexed. A characteristic clinical picture may be present, depending on the level of nerve root involvement (Table 8-2). The sensory examination may reveal diminished sensation along the affected dermatome, although the sensory examination is usually not very helpful. The various tests measuring sciatic nerve root tension are frequently positive if herniation is causing nerve compression (Fig. 8-9).

SPECIAL STUDIES

NOTE: The number of symptomatic conditions discovered by special studies but not suspected clinically is very small. Tests such as MRI and EMG should only be performed as adjuncts to the clinical assessment.

TREATMENT

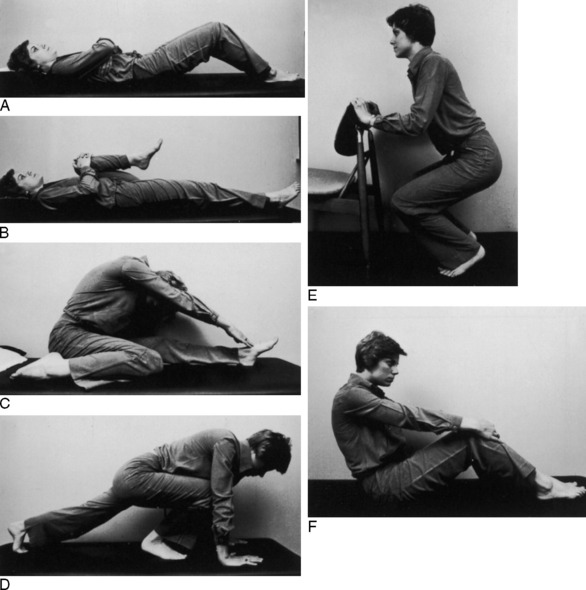

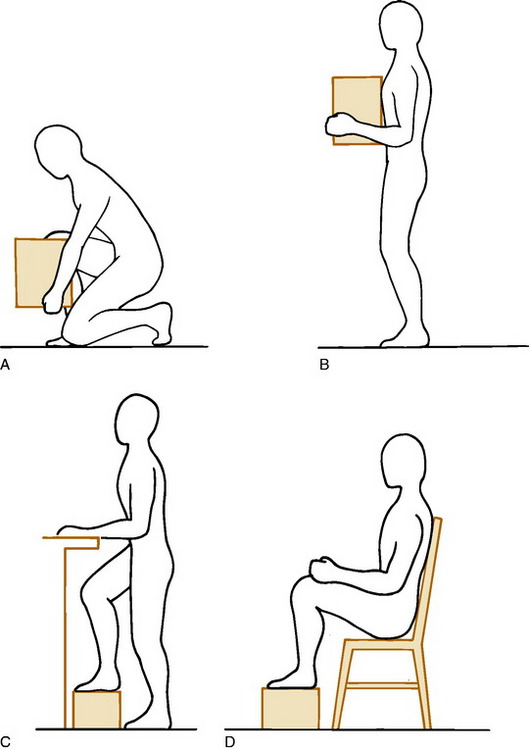

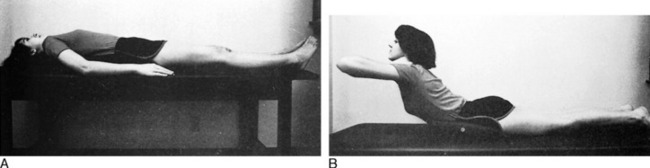

The initial treatment is always conservative, and the majority of patients respond well. Treatment is based on the symptoms of the patient and not on any imaging study. Extended periods of inactivity are no longer recommended for most low back disorders, but a short period of bed rest (5 to 10 days) may be very helpful in the treatment of acute disc herniation, mainly if radicular leg pain caused by nerve root compression is present. This is followed by a careful exercise program. While the patient is in bed, the hips and knees are kept moderately flexed. Lying on the abdomen, which increases the lumbar lordosis, is avoided. Hip flexion and pelvic tilt exercises are begun within the limits of pain (Fig. 8-11). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, and moist heat are used as necessary. Narcotics may even be required in cases of nerve root compression and intense leg pain. If improvement occurs, which it does in the majority of cases, gradual resumption of activity is allowed, and the exercise program is expanded. Physical therapy is often useful, mainly for the exercise program. Modalities such as deep heat and massage can be added for their “hands-on” appeal. A lumbosacral corset may be temporarily used. (There is no evidence that continued use of any brace promotes back weakness, however, especially if the patient adheres to an exercise program.) Recurrences are prevented by a proper exercise program and the avoidance of stress to the lower part of the back (Fig. 8-12).

SUMMARY

CHRONIC LUMBAR DISC DISEASE

A high percentage of adults older than 40 years of age have degenerative disc disease at one or more levels on roentgenographic examination (Fig. 8-13). Significant thinning of the disc accompanied by osteophyte formation is often present. And MRI studies commonly reveal “bulging” disc abnormalities in patients, many of whom are without symptoms. These roentgenographic changes are common in the general population and are present in 30% to 40% of normal individuals. They are so common, in fact, that some question whether or not lumbar disc disease should be considered a “disease” or simply a change which occurs with age. Disc degeneration and the accompanying changes in the adjacent facet joints with soft tissue inflammation can, however, lead to intermittent low back pain and even nerve root irritation or compression with leg pain. The severity of the symptoms often bears no relation to the severity of the radiographic findings, however.

Pain of this nature usually responds to conservative management. NSAIDs, analgesics, rest, moist heat, and the use of a lumbosacral corset may be the only treatment necessary. Exercises, education, and postural training are important. Risk factors associated with chronic back pain should be addressed, such as smoking and poor physical conditioning. A physical therapist can be helpful in this regard. When signs of nerve root irritation with radicular pain are present, compression or irritation of the root by a small, acute, soft disc herniation or degenerative osteophyte should be suspected. The leg pain often responds well to epidural pain blocks. Surgical intervention is occasionally indicated to relieve nerve pressure. Arthrodesis of the adjacent vertebrae may rarely be indicated to relieve chronic low back pain by stabilizing the degenerated painful disc segment but the procedure is highly controversial (see Chapter 18). Conservative treatment is usually successful in most cases. Recurrences are not uncommon and generally respond to medical management.

LUMBAR SPINE STENOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES

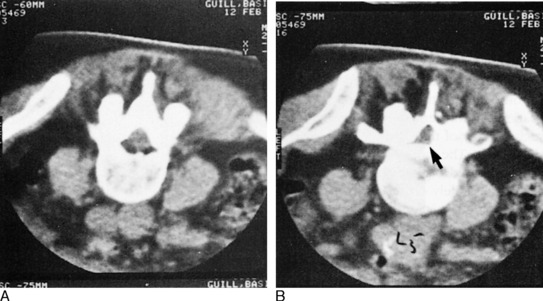

Roentgenographic examination of the lumbar spine usually reveals degenerative changes throughout the lower part of the back. EMG and myelography may help localize the disorder, and CT scanning is frequently diagnostic (Fig. 8-14). MRI is also helpful.

THE FACET SYNDROME

The small articular facet joints of the spine have occasionally been implicated as a cause of chronic low back pain. They may become affected secondary to disc thinning and frequently develop arthritis. And even though arthropathy is a common finding in these joints, the relationship of this abnormality to back pain has been difficult to prove. As a result, many doubt the existence of this disorder. The patient is often one who has a long history of chronic spine pain that has not responded to the traditional methods of management. Clinically, there may be local facet tenderness and pain on side bending. To alleviate the symptoms, injection and even denervation of these joints have occasionally been performed. The results of these treatments are only modestly successful.

Lumbar Strain

With a daily program of proper postural exercises, weight loss, and a general exercise program, most patients who develop chronic back pain will be able to rehabilitate the lower part of the back. The use of modalities (hot packs, massage, etc.) in physical therapy is discouraged, although short-term use may allow the exercise program to be more easily implemented. Full cooperation is necessary.

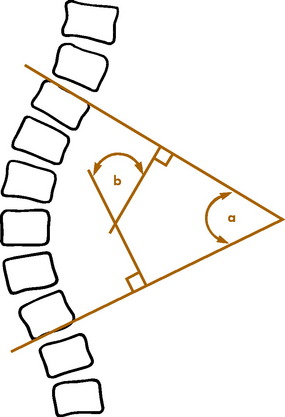

Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

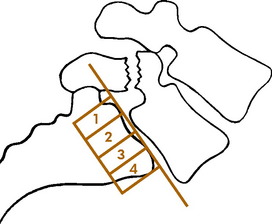

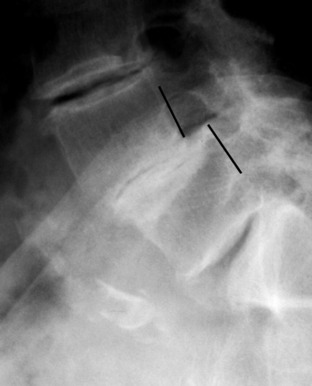

Spondylolisthesis is a disorder, usually in the lumbar spine, in which one vertebra gradually slips on another. Several types have been described (congenital, degenerative, pathologic, traumatic, and spondylolytic). However, most spondylolisthesis is secondary to spondylolysis, which represents a fibrous defect in the pars interarticularis or isthmus of the vertebra (Fig. 8-15). The disorder is therefore probably acquired and not congenital. The development of this defect has a hereditary predisposition and usually becomes manifested as the result of impact loading and extension stresses to the lower part of the back. These cause the development of an overuse fatigue fracture, usually bilateral, at the isthmus that fails to heal, resulting in a fibrous nonunion. It is most common at L5-S1. It develops in the teenage years, but may not become symptomatic until years later, if at all. It is often associated with lumbosacral anomalies such as transitional vertebrae and spina bifida occulta. There is an increased incidence in football players and gymnasts, possibly from hyperextension and chronic overload. If the defect is bilateral, forward displacement (spondylolisthesis) can occur. Spondylolisthesis is classified according to the amount of forward slippage of the affected vertebra (Fig. 8-16). An increase in slippage often occurs during the adolescent growth spurt but is rare after maturity.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Spondylolysis may be symptomatic even without spondylolisthesis, and both conditions may be associated with lumbar disc herniation. The disorder is often asymptomatic, however, and is frequently discovered incidentally in adults on roentgenograms taken for other purposes. When it is seen on roentgenograms taken as a part of a routine evaluation for back pain, it is often difficult to determine whether or not it is playing any role in the patient’s complaints.

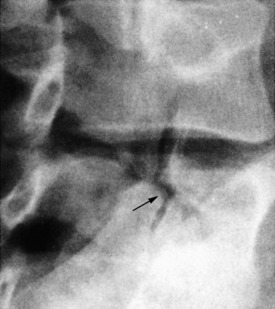

Roentgenograms reveal the typical findings of a defect in the pars interarticularis on both sides, which may be accompanied by forward slippage (Fig. 8-17). Unilateral defects are unusual. The classic findings of periosteal new bone present in stress fractures of long bones are rarely seen in the spine. A bone scan may be positive if the lesion is “acute” in the adolescent. MRI may be indicated in cases of negative bone scan to rule out other causes of pain. CT is also helpful to assess healing potential.

DEGENERATIVE SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

This type of spondylolisthesis results from disc degeneration and narrowing. When the process of disc “settling” is uneven, spondylolisthesis can develop (Fig. 8-18). The signs and symptoms are those of degenerative disc disease, sometimes accompanied by those of stenosis. Although many patients are pain-free, low back and occasionally radicular leg pain may develop. The treatment is the same as that for chronic degenerative disc disease and stenosis.

Back Pain in the Workplace

A variety of terms have been used to describe this condition, including “chronic benign industrial back pain” and “chronic pain syndrome.” This terminology partly reflects the difficulty in assigning a specific diagnosis and cause for the pain. A part of this difficulty, in turn, is a result of the fact that low back pain in general, and especially back pain in the workplace may be the result of a variety of biomechanical, biochemical, behavioral, socioeconomic, and psychophysiologic factors. In addition, trying to distinguish between a work injury and a normal disease of life can have profound implications for the patient.

EVALUATION

Physical findings are often nonspecific. There is usually generalized low back tenderness and diminished range of motion. Sometimes, the physical findings are “nonanatomic” in nature. Waddell signs are often cited when nonorganic physical findings are present (Table 8-3). There is usually no neurologic deficit, and sciatic tension tests are generally normal but may be difficult to assess.

| These findings should not be taken as a sign that no illness is present, but simply that this may be a way that patients can show how bad it is to them. |

SPECIAL STUDIES

All of the anatomic structures of the lower part of the back (discs, ligaments, facet joints, bone, and muscle) can be the source of pain. The intervertebral disc is thought by many to be the source of most low back pain. Unfortunately, as many as 35% of asymptomatic adults will have abnormal findings on myelography, CT, or MRI that are usually related to the disc. This makes evaluation of this problem difficult, and it is felt by many that in the majority of cases, the exact underlying pathology probably cannot be determined and the condition is simply called “idiopathic.” Initially, a routine roentgenographic examination should be performed in 2 to 4 weeks if the patient does not improve, mainly to rule out any serious disorder. Further studies (EMG, CT, MRI, bone scan, myelography) should be performed only as adjuncts to the physical examination and history. The yield of clinically useful information from these studies is often poor. Subjecting patients to further extensive testing in a search for the exact etiology of their pain is likely to be futile, sometimes painful, and always costly. Diagnosing a spinal disorder solely on the basis of any of these tests should be avoided. It is rare that these special tests clearly demonstrate a source for the pain when it is not suspected clinically. In addition, any treatment (e.g., surgery) based solely on a special study will often fail. In general, myelography and other special studies should be used only under the following circumstances: (1) if surgical disc removal is contemplated for intractable leg pain or a serious neurologic deficit, or (2) if other serious spinal abnormality is suspected.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Thoracic Disc Disease

CLINICAL FEATURES

Only axial dorsal spine pain occurs in most cases. With central herniation and myelopathy, however, gradually increasing motor weakness in the lower extremities becomes apparent. Sphincter control may be lost, and diffuse numbness is common. Sensory testing may help determine the level of involvement. Examination usually reveals limited motion in the dorsal spine. Major neurologic deficits may be present in the lower extremities (spasticity, clonus). Roentgenographic examination often reveals calcification, narrowing, and spondylosis in the dorsal spine. Myelography may reveal a complete block in central lesions. MRI is often needed.

Scoliosis

CLINICAL FEATURES OF IDIOPATHIC SCOLIOSIS

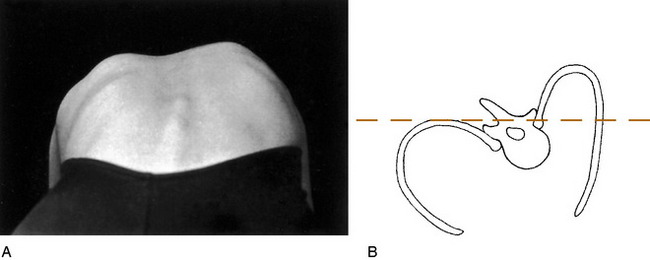

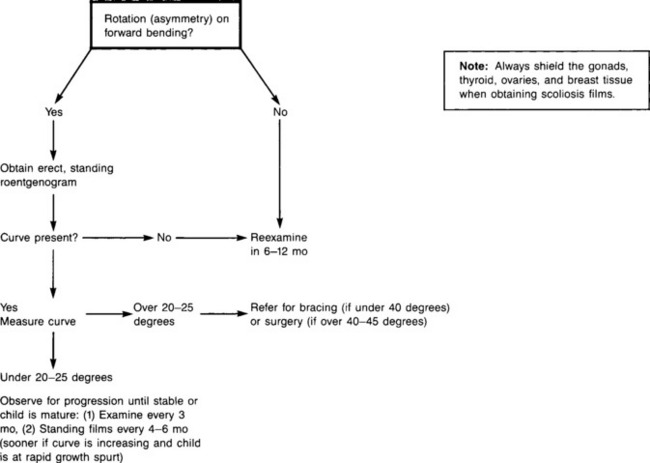

The diagnosis is usually made on routine physical examination. Attention should be focused on the problem in all children, but especially in those between the ages of 10 to 14 years, when spinal growth is most rapid. For the examination, the patient should be undressed to the waist or wear a bathing suit, and a routine should be followed. The shoulders and iliac crests are inspected to determine whether they are level. The scapulae, rib cage, and flanks are then observed for symmetry. The spinous processes are palpated to determine their alignment. The patient is then asked to bend symmetrically forward at the waist with the arms hanging free (Fig. 8-19). Observation from the back or front will detect the spinal rotation in the form of a rib hump or abnormal paraspinal muscular prominence. Height measurements are taken initially and at all follow-up visits to gauge the growth rate of the patient and assess the risk of rapid progression of the curve. Additional data should be obtained regarding skeletal and sexual maturity (onset of menses, etc.).

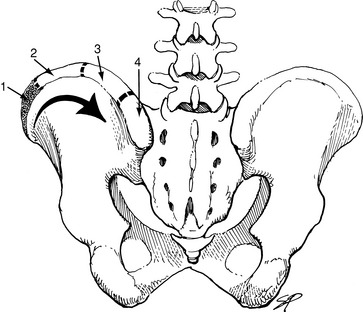

The diagnosis is confirmed, and the degree of curvature is measured by a standing roentgenogram of the spine (Fig. 8-20). There is no other method of determining the severity of the curve, and a patient should never leave the office without an accurate roentgenographic measurement of the curvature. The roentgenogram may have to be repeated at intervals to determine whether or not the curve is progressive. Breasts and gonads should be shielded when films are done. The degree of skeletal maturity can be determined by assessing the status of the iliac apophysis using the Risser sign (Fig. 8-21).

MRI is usually not indicated unless there is some evidence for a secondary cause of the curve: (1) significant pain, (2) abnormal neurologic symptoms or findings, (3) a left thoracic curve (which is often associated with an underlying spinal disorder), or (4) rapid progression.

NATURAL HISTORY

Although it is impossible to accurately predict the outcome of most curves, the following facts are known about scoliosis:

TREATMENT

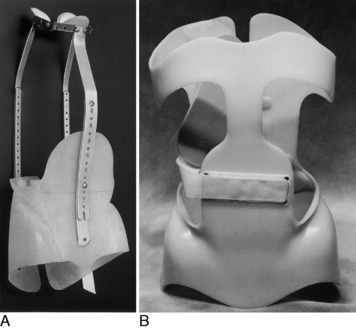

The treatment depends on the age of the patient and the severity of the curve (Fig. 8-22). In the immature patient, frequent observation is necessary until the curve reaches 20 degrees. Curvatures more than 20 to 25 degrees may require treatment, depending on age and maturity. (The older child whose growth has slowed might only be observed if the curve is not excessive.) The curve can be stabilized and, in some cases, improved by spinal bracing, but full, permanent correction is not possible or necessary. The Milwaukee brace or a thoracolumbosacral orthotic (TLSO) is commonly used for this purpose (Fig. 8-23). The newer underarm orthotics are more easily accepted by the young patient because of their low-profile design. Treatment in the brace is continuous for 23 hours a day, and the brace may have to be worn for 2 years or longer. Exercises are performed in the brace to improve the cosmetic appearance and decrease the curvature, although the family needs to understand that the treatment will not eliminate the curve. Exercises alone will produce no change in the curvature, nor will they prevent any progression without the brace. Excellent results are obtained with proper use of the brace in curvatures between 20 and 40 degrees. It will not fully correct the curve, but it will usually prevent the curve from progressing to the stage where spinal surgery is necessary. Curves greater than 45 degrees cannot be effectively braced. Thus, early detection and treatment are important. Successful nonsurgical management maintains the spinal flexibility that spinal fusion eliminates.

Kyphosis

SENILE KYPHOSIS

Sometimes called round back of old age, senile kyphosis results from multiple areas of disc degeneration at the thoracic level. It is relatively common in the elderly patient and may be symptomatic. Roentgenograms often reveal thinning of the discs and osteoporosis with mild wedging deformities (Fig. 8-24). Treatment is directed toward maintaining good posture. Exercises that strengthen the back and abdominal muscles are often helpful. The use of a light spinal brace will frequently relieve the symptoms.

POSTURAL ROUND BACK

“Faulty posture” is common in adolescents and young children. It probably occurs as a result of minor muscular imbalances and weakness. The typical picture is one in which the patient, often a teenager, shows an increase in the normal dorsal kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and an increased pelvic inclination. The parent often complains that the child does not sit straight, but there is generally no pain. The patients are often asthenic. Frequently, there are no specific findings, but sometimes, the shoulders are rounded and drooped, and the abdomen may be protuberant. The scapulae are frequently prominent. The kyphosis is typically supple and corrects with hyperextension in contrast to the nonflexible, fixed kyphosis in Scheuermann’s disease. Roentgenograms of the dorsal spine are usually unremarkable. No wedging or end-plate irregularities tend to be present.

After ruling out other causes of kyphosis, the patient is reassured and started on an exercise program to overcome any contractures and decrease the lumbar lordosis (Fig. 8-25). The disorder usually responds well to the exercises.

SCHEUERMANN’S DISEASE

CLINICAL FEATURES

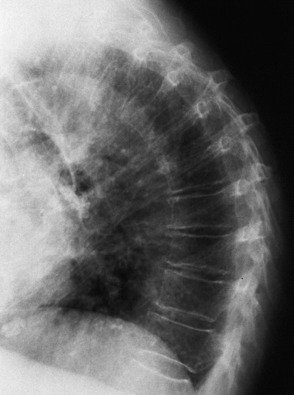

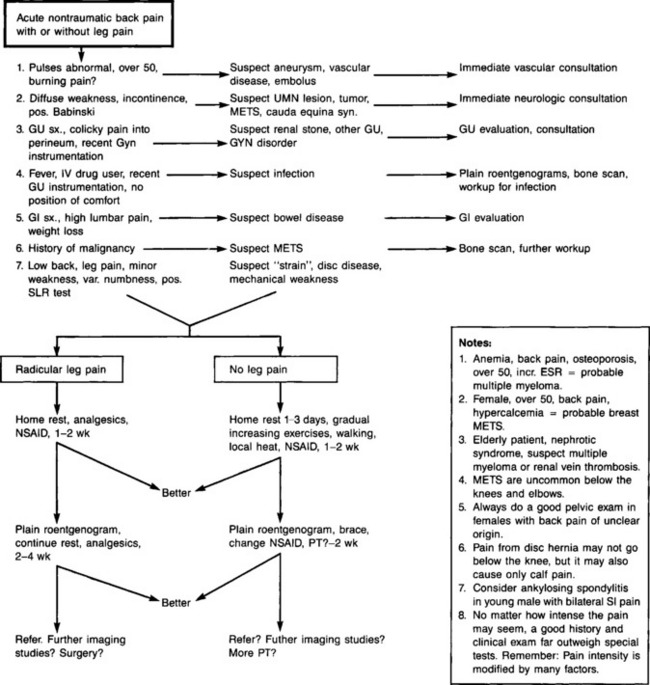

A positive diagnosis is possible only with a roentgenographic examination. Wedging of the vertebrae, irregularity of the end plate, and typical Schmorl’s nodules are seen on the lateral view, usually between T2 and T12 (Fig. 8-26). Synostoses and osteophyte formation are not uncommon in the adult patient.

Lumbosacral Anomalies

A variety of minor congenital abnormalities may exist in the lumbar spine and at the lumbosacral junction. The majority of these occur at the lumbosacral region, and most are asymptomatic. Facet joint asymmetry, variations in the number of lumbar vertebrae, spina bifida occulta, and transitional lumbosacral vertebrae are among the more common anomalies seen on routine roentgenograms. Only the transitional vertebra appears to be possibly related to low back pain.

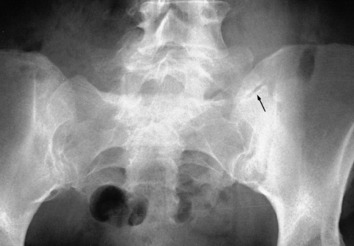

The transitional vertebra (lumbarized S1 or sacralized L5) may produce pain at the false joint that forms at the articulation between its elongated transverse process and the sacrum (Fig. 8-27). The disc between this vertebra and the sacrum is usually markedly thinned but is rarely the cause of symptoms. The treatment is usually conservative. A lumbosacral corset may be beneficial by restricting motion at this area.

Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies

ANKYLOSING SPONDYLITIS

An early diagnosis is often difficult because of the insidious onset of the disease. Years may pass between the onset of symptoms and the ultimate diagnosis because of the frequency of nonspecific back pain from other disorders. The pain is usually located low in the buttocks and thigh region but rarely radiates into the calf or foot. Often the disease is mild, and there may be few systemic symptoms; however, in a severe form, fatigue, weight loss, anorexia, fever, and other systemic complaints may accompany the onset. A few patients have difficulty taking a full breath. Although peripheral joint involvement may be present before the development of pain in the sacroiliac region, the diagnosis can only be presumptive until the sacroiliac joints are involved to such a degree as to be demonstrated roentgenographically. Although this disease is more common in men, women who have ulcerative colitis have an extremely high incidence of developing this disorder.

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

The early roentgenographic features are usually those of bilateral sacroiliitis. Initially, there are erosions of these joints, and they lose their clear-cut demarcation because of cystic changes and subchondral sclerosis. (MRI is the most sensitive study for detecting early ankylosing spondylitis and should be considered whenever the history is suggestive, but plain films are normal.) The vertebral bodies may also become demineralized, and a typical squaring of the anterior vertebral bodies develops. Apophyseal joint irregularities and paraspinal ligamentous calcifications develop later, and eventually there may be complete fusion of the sacroiliac and hip joints as healing takes place following the inflammation. As the disease progresses, calcifications of the anulus fibrosis and ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament develop, which give rise to the so-called bamboo-spine appearance characteristic of ankylosing spondylitis (Fig. 8-28).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Reiter’s Syndrome is similar to psoriatic arthropathy in that sacroiliac joint involvement usually occurs late. The small and large joints, particularly of the lower extremity, are affected, and skin lesions are usually specific. Uveitis may occur, and urethritis is present at least at some point in the illness. Aortitis may occur, but pulmonary fibrosis has not been reported.

TREATMENT

PROGNOSIS

Early diagnosis, good long-term management, frequent follow-up examinations (including helping the patient understand the disease), exercise, and the appropriate medications usually provide the patient with a normal life span. Death may occur as a result of the development of aortic insufficiency or secondary amyloidosis with chronic renal disease. If valvular disease develops, the patient should be educated regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis. The usual course of the disease is not life threatening, however, and a relatively normal lifestyle and work load are generally possible.

PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS

Psoriasis may occasionally be accompanied by an inflammatory arthritis that affects both the axial skeleton and the peripheral joints (see Chapter 14). Spondyloarthropathy develops in 20% to 40% of cases and can affect any part of the spine. Sacroiliitis is often present and may be asymmetric. The prevalent age is between 30 and 55 years. The skin disorder usually precedes the arthritis by several years. Males and females are equally affected. Between 5% and 10% of patients with psoriasis will develop arthritis, which is much more common in patients with severe skin disease. Peripheral arthritis is very common and is usually polyarticular, involving the small joints of the hands and feet, and although it often runs a benign course in many patients, a very destructive form can occur, especially in the hand (arthritis mutilans). Dystrophic changes in the nails with pitting and ridging develop in many patients with DIP involvement.

Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

CLINICAL FEATURES

Many patients have had minor symptoms of DISH for years before the condition is diagnosed. The primary complaints are those of low-grade spinal stiffness and pain, although the symptoms and signs are often relatively minor despite extensive hypertrophic spur formation. The thoracic spine is most often affected, most commonly on the right side. The presence of large anterior cervical osteophytes may lead to dysphagia (Fig. 8-29). Cervical myelopathy may result from ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Other potential sequelae include lumbar stenosis and serious cervical spinal cord injuries, often associated with minor trauma. Peripheral joint symptoms are usually mild, although heel and elbow pain are often the presenting complaints. Extraspinal manifestations also include an increased risk of heterotopic ossification There are no diagnostic laboratory tests.

Multiple Myeloma

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC FEATURES

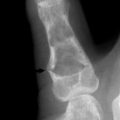

The classic finding is the “punched-out” lesion with sharply demarcated edges (Fig. 8-30). Usually, multiple lesions are found, but in 10%, only a single skeletal defect may be present. Diffuse osteoporosis because of generalized demineralization is the only finding in about 25% of cases. The typical lesions may occur in any part of the skeleton but are most common in the spine, skull, ribs, and pelvis. Pathologic fractures are common. Intervertebral body collapse may result in nerve root or cord compression. Diffuse bony involvement may even result in hypercalcemia. Using the bone scan to assess the disorder is helpful, but a negative scan can be misleading. This tumor is often “cold” on a bone scan because of its rapid destruction. Plain films are often better for evaluation. CT and MRI are also helpful.

LABORATORY FINDINGS

In approximately half of the cases, the urine contains the Bence Jones protein, which has the unique property of precipitating in an acid pH when the temperature is between 4.4°C and 15.6°C and redissolving when the temperature is 32.2°C. Anemia is often present, and the sedimentation rate is usually elevated. Serum protein electrophoresis usually displays the characteristic dysproteinemia. The serum calcium concentration is occasionally elevated, but the alkaline phosphatase level is usually normal.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is of multifactorial origin and is usually classified as primary or secondary. The primary type is the form most often seen in the older population. It is further classified as type I or II, although there is considerable overlap between the two forms. Type I develops as a result of estrogen loss, which allows increased osteoclastic bone resorption. Type II is the result of a slow, progressive decline in osteoblastic activity with normal aging. Unfortunately, the elderly female often suffers the effects of both.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has established an operational definition depending on BMD (bone mineral density), commonly expressed as a T-score (Table 8-4). A T-score represents a patient’s bone density expressed as the number of standard deviations (SD) above or below the mean BMD value of normal young adults. After menopause, all women should be evaluated clinically for osteoporosis risk to determine the need for BMD testing.

Table 8-4 World Health Organization Diagnostic Criteria for Women Without Fragility Fractures

| Diagnosis | BMD Criteria |

|---|---|

| Normal | BMD value within 1 SD of the young adult mean |

| Osteopenia | BMD value between −1 SD and −2.5 SD below the young adult mean |

| *Osteoporosis | BMD value at least −2.5 SD below the young adult mean |

BMD, Bone mineral density.

* Women in this group who have already experienced one or more fractures are deemed to have severe or “established” osteoporosis.

FACTORS AFFECTING BONE MASS

A number of factors can influence peak bone mass or contribute to bone loss in the adult in addition to hormonal deficiency. In general, the more risk factors a woman has, the greater her likelihood of osteoporotic fracture (Table 8-5). Secondary osteoporosis can also result from a number of medical conditions and from complications from the use of several medications (Table 8-6).

Table 8-5 Major Risk Factors for Osteoporosis and Related Fractures in White Postmenopausal Women

| Personal history of fracture as an adult (>40–45 year age) |

| History of fragility fracture in a first-degree relative |

| Low body weight (<about 127 lbs) |

| Current smoking; alcohol more than two drinks per day |

| Use of oral corticosteroid therapy (>7.5 mg prednisone or its equivalent) for more than 3 months |

| Impaired vision, recent falls |

| Estrogen deficiency at an early age (<45 year) and prolonged premenopausal amenorrhoea (>1 year) |

| Dementia |

| Poor health/frailty/low physical activity |

| Low calcium intake (lifelong) |

Table 8-6 Causes of Secondary Osteoporosis

| Drugs (alcohol, steroids, heparin, anticonvulsants, cytotoxins, lithium, total parenteral nutrition, aluminum) |

| Disuse-prolonged immobilization |

| Malignancy (multiple myeloma,leukemia, lymphoma), mastocytosis |

| Endocrine disease (diabetes, thyroid disease, eating disorders, exercise-induced amenorrhea, Cushing’s syndrome, hyperparathyroidism). |

| Gastrointestinal disorders (gastrectomy, sprue, malabsorption syndromes, inflammatory conditions, liver disease) |

Both men and women experience an age-related decline in BMD starting in midlife. Women experience more rapid bone loss in the early years following menopause, which places them at earlier risk for fractures. Men and perimenopausal women with osteoporosis more commonly have secondary causes for the bone loss than do postmenopausal women. Among men, 30% to 60% of osteoporosis is associated with secondary causes; the most common are hypogonadism, use of glucocorticoids, and alcoholism. In perimenopausal women, more than 50% have secondary causes, most often caused by hypoestrogenemia, glucocorticoids, thyroid hormone excess, and anticonvulsant therapy. In postmenopausal women, the prevalence of secondary conditions is thought to be much lower, but the actual proportion is not known. Glucocorticoid use is the most common form of drug-related osteoporosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The midback vertebrae T12 to L3 are the most common fracture sites, followed by T6 to T9 (Fig. 8-31). The rare osteoporotic fracture in the upper thoracic spine may be indicative of an underlying malignant tumor and may necessitate MRI studies. There is little correlation between the degree of collapse of the vertebral body and level of pain. Overall, 20% of women experience another vertebral fracture after their first fracture. They are also at increased risk for nonvertebral fracture. Eventually, vertebral collapse may cause the characteristic loss of body height, protuberant abdomen, and dorsal thoracic kyphosis called “dowager’s” hump. After achieving maximum height, most midlife women and men will lose 1 to 1½ inches of height as part of their normal aging process, primarily as a result of shrinkage of interverbral disks. In otherwise asymptomatic women, a height loss greater than 1½ inches may be associated with compression fractures of vertebra(e). Excessive kyphosis may even allow the rib cage to shift downward leading to restrictive lung disease. This sagging also prevents comfortable expansion of the stomach after eating and causes early satiety, which further limits nutritional intake. A rib–pelvis distance of less than 2 fingers’ width and inability to touch the occiput to wall when standing against the wall suggests the presence of compression fracture.

In the early postmenopausal state, the incidence of fracture of the distal radius is also high. Because the femur is composed of both cortical and cancellous bone, hip fractures usually develop years later, after age 65. Most (80%) of all hip fractures are associated with osteoporosis. Oral alveolar bone loss (which can lead to tooth loss) is strongly correlated with osteoporosis. Even in women without osteoporosis, there is a correlation between spinal bone density and number of teeth. Overall tooth counts are easy to do, and a tooth count less than 20 should suggest the need for further screening for osteoporosis.

EVALUATION

BONE DENSITY MEASUREMENT

Currently, there is no accurate measure of overall bone strength. BMD is frequently used as a proxy measure and accounts for approximately 70% of bone strength. There is a 50% to 100% increase in fracture risk for each SD decline in bone density (approximately 0.1 g/cm bone mass). Although low bone density reliably predicts the risk of fracture, increase in bone density in response to treatment does not demonstrate a direct correlation with a reduction in fractures. Therefore, a few percentage point differences achieved by various treatments have little clinical meaning. Keep in mind that because the rate of bone loss after menopause contributes equally to the risk of fracture as the total bone mass present at the time of the menopause, a normal bone density measurement at the time of menopause does not mean that the patient will not be at risk of fracture later in life.

Biochemical Markers

There are many serum and urinary biochemical markers of bone turnover. They include markers of bone formation and those of resorption. Markers of bone formation include serum osteocalcin, total and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, and procollagen peptide. Bone formation markers are useful in monitoring the effects of PTH, which rapidly increases bone formation and later bone resorption. Bone resorption is indicated by changes in urinary calcium, hydroxyproline, pyridinoline, deoxypyridinoline cross-link collagen, telopeptides of collagen, and serum cross-linked telopeptides. Generally, serum tests, when available, are preferably to urinary tests because of their lower assay coefficient of variation and lower propensity of diurnal variation. These markers cannot diagnose osteoporosis or predict bone density or fracture risk. Currently, the precise role of biochemical markers in the clinical management of osteoporosis is not established, but they may be useful for the following situations:

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT

Additional measures include the following:

MANAGEMENT OF OSTEOPOROTIC FRACTURES

For acutely symptomatic fractures, treatment with analgesics is required. A few small, randomized clinical trials suggest that calcitonin may reduce pain related to acute vertebral compression fracture. Short periods of bed rest may be helpful for pain management, but in general, early mobilization is recommended as it helps prevent further bone loss. Occasionally, use of a soft elastic-style brace may facilitate earlier mobilization. Muscle spasms often occur with acute compression fractures and can be treated with muscle relaxants and heat treatments. Various physical modalities, such as ultrasound and transcutaneous nerve stimulation, may be beneficial in some patients.

Hormone treatment

While progestional agents are considered antiestrogenic, they have been reported to act independently, in a manner similar to estrogen, to reduce bone resorption. When added to estrogen, progestins can lead to an apparent synergistic increase in bone formation associated with a positive balance of calcium. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) showed a 33% reduction in vertebral fractures, a 33% reduction in hip fractures, and a 24% overall reduction of fractures with estrogen–progestin combination treatment. It also showed that combined estrogen–progestin treatment increased the risk of fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction by about 29%, confirming data from other studies. Other important relative risks included a 40% increase in stroke, 100% increase in venous thromboembolic disease, 26% increase in risk of breast cancer, and a twofold increase in dementia. Benefits other than the fracture reductions included a 37% reduction in risk of colon cancer. It is important to note that the WHI findings apply specifically to hormone treatment in the form of conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate.

Bisphosphonates

The approved dosage of alendronate for prevention of bone loss in new postmenopausal women and for treatment of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis in men and estrogen-replete women is 5 mg daily or 35 mg weekly. For treatment of established postmenopausal osteoporosis and for treatment of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis in estrogen-deficit women, the dose is 10 mg daily or 70 mg weekly. Risendronate is given either as 5 mg daily or 35 mg weekly for both prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Contraindications to the use of these drugs include hypersensitivity to the drugs, hypocalcemia, inability to follow the dosing regimen (i.e., inability to stay upright for 30 minutes after the medicine is given), and the presence of esophageal abnormalities that might delay the transit of the tablet (e.g., achalasia, stricture). It is relatively contraindicated in presence of upper gastrointestinal tract disease.

Follow-up

When DEXA is used, a BMD difference between measurements must be in the range of 3% to 5% to be clinically significant. For patients with normal baseline BMD, consider a follow-up measurement every 3 to 5 years. Patients whose bone density is well above the minimal acceptable level may not need further BMD testing. For patients in an osteoporosis prevention program, perform a follow-up every 1 to 2 years until bone mass stability is documented. After BMD has stabilized, perform a follow-up measurement every 2 to 3 years. For patients on a therapeutic regimen, perform a follow-up measurement yearly for 2 years. If bone mass has stabilized after 2 years, perform a follow-up measurement every 2 years. Otherwise, continue with annual follow-up measurement until stability is achieved.

Other Forms

An unusual type of regional osteoporosis is so-called Sudek’s atrophy, a result of reflex sympathetic dystrophy that is commonly found in the hands and feet (see Chapter 18). This localized osteoporosis is characteristically associated with the other findings of RSD, such as swelling, excessive sweating, and pain. Bone scanning may reveal increased flow to the affected area, a finding that may confirm the diagnosis of reflex dystrophy.

Tumors of the Spine

METASTATIC BONE DISEASE

Roentgenographs often reveal the lesion, but 30% to 50% of the bone must be destroyed before the lesion is visualized on plain films. The bone scan is positive in 90% of cases. False negatives commonly occur in myelomas and many carcinomas because these tumors produce such rapid and extensive bone destruction that new bone formation and the reparative process do not occur. (Technetium scanning relies on bone repair.) CT and MRI scans will usually reveal the lesion.

Back Pain from Other Origins

ABDOMINAL DISORDERS

An aneurysm of the aorta may cause not only acute abdominal pain and collapse with abdominal rigidity but also back pain (Fig. 8-32). Generally, the pain is thoracic but may be higher or lower depending on location. There may be an absence or reduction of pulses in one of the lower extremities, and a pulsatile mass is often present.

GENITOURINARY DISORDERS

Renal diseases are among the most common nonorthopedic disturbances to simulate back disease. The pain of renal colic, caused by the passage of a small stone, clot, pus, or crystals, is usually ipsilateral and felt in the flank and lumbar area. It often radiates into the corresponding groin and testicle or vulva. Vomiting and restlessness are common, and there may be frequency and pain on urination. It is sometimes accompanied by hematuria. A positive Murphy’s punch is diagnostic. Renal stones are rare in children, and when they occur, the patient should be evaluated for underlying metabolic disorders such as cystinuria. Acute pyelonephritis frequently causes low back pain, but systemic and urinary symptoms usually clarify the diagnosis. Chills, fever, urinary frequency and urgency, and pain and tenderness in the costovertebral angle are usually present.

Back pain occasionally accompanies prostate disorders. Prostatitis may evoke sacral pain, sometimes radiating into one leg. It is usually accompanied by frequency, and there may be prostatic discharge. Prostate carcinoma with metatases to the lower portion of the back is another cause of lumbar or sacral pain. Most prostatic disorders are diagnosed by rectal examination, which should always be performed, especially for those patients whose back pain is unexplained.

Pregnancy, ectopic or otherwise, should always be ruled out in women of childbearing years, especially if invasive or roentgenographic studies are being planned. A well-performed pelvic examination will help separate the majority of these disorders (Fig. 8-33).

Aho K, Ahvonen P, Lassus A, et al. HL-A antigen 27 and reactive arthritis. Lancet. 1973;2:157.

Ansell BM. Rheumatic disorders in childhood. Clin Rheum Dis. 1976;2:303.

Arnett FCJr. The implications of HL-A W27. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:94-95.

Avioli LV. Senile and postmenopausal osteoporosis. Adv Intern Med. 1976;21:391-415.

Bernat JL. A dangerous backache. Hosp Pract. 1977;12:36-37.

Blount WP, Moe JH. The Milwaukee brace. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1973.

Bondilla KK. Back pain: osteoarthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1977;25:62-66.

Brewerton DA, Caffrey M, Nicholls A, et al. Reiter’s disease and HL-A 27. Lancet. 1973;2:996-998.

Brown MD. Diagnosis of pain syndromes of the spine. Othrop Clin North Am. 1975;6:233-248.

Calabro JJ, Amante CM. Indomethacin in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1968;11:56-64.

Cuellar ML, Espinoza LR. Management of spondyloarthropathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1996;8:288-295.

Curtis P. Low back pain in the primary care setting. J Fam Pract. 1977;4:381-382.

Deen HGJr. Diagnosis and management of lumbar disk disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:283-287.

Dickson RA. Conservative treatment for idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Surg Br. 1985;67:176-181.

Dyck P, et al. Intermittent cauda equina compression syndrome. Spine. 1977;2:75.

Early SD, Kay RM, Tolo VT. Childhood diskitis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:413-420.

Fast A. Low back disorders: conservative management. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:880-891.

Ferris B, Edgar M, Leyshon A. Screening for scoliosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1988;59:417-418.

Greipp PR. Prognosis in myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:895-902.

Hart FD. The ankylosing spondylopathies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1971;74:7-13.

Harvey MA, James B. Differential diagnosis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1972.

Heaney RP. A unified concept of osteoporosis. Am J Med. 1965;39:877-880.

Heaney RP. Nutrition and catch-up bone agumentation in young women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:523-524.

Hedequist D, Emans J. Congenital scoliosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:266-275.

Hurley DL, Khosla S. Update on primary osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:943-949.

Kataria RK, Brent LH. Spondyloarthropathies. Am Fam Physician. 2004;15:2853-2860.

Kertesz A, Kormos R. Low back pain in the workman in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;115:901-903.

Lane JM, Vigorita VJ. Osteoporosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:274-278.

Leutwek L, Whedon GD. Osteoporosis. April 1963. DM

Macnab I. Backache. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1977.

Madore GR, Sherman PJ, Lane JM. Parathyroid hormone. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:67-71.

Maksymowych WP. Update on spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:143-146.

Malpas JS. Problems in the management of myeloma. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65:468-470.

McCulloch JA. Chemonucleolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977;59:45-52.

Meyerding HW. Spondylolisthesis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1932;54:371.

Mooney V. Percutaneous discectomy. Spine. 1989;3:103.

Nachenson AL. The lumbar spine, and orthopedic challenge. Spine. 1976;1:59.

Nash CLJr. Current concepts review: scoliosis bracing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:848-852.

Nelson MA. Lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1973;55:506-512.

Ogryzlo MA, Rosen PS. Ankylosing (Marie-Strumpell) spondylitis. Postgrad Med. 1969;45:182-188.

Radin EL. Reasons for failure of L5-S1 intervertebral disc excisions. Int Orthop. 1987;11:255-259.

Resnick NM, Greenspan SL. ‘Senile’ osteoporosis reconsidered. JAMA. 1989;261:1025-1029.

Riggs BL, Melton LJ3rd. Involutional osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1676-1686.

Ruge D, Wiltse LL. Spinal disorders: diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1977.

Schurman DJ, Nagel DA. Low back and leg pain. Prim Care. 1974;1:549-563.

Sewell KL. Modern therapeutic approaches to osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1989;15:583-614.

Sim FH. Metastatic bone disease. Philosophy of treatment. Orthopedics. 1992;15:541-544.

Singer FR. Page’’s disease of bone. New York: Plenum Publishing Corp, 1977.

Smith L. Enzyme dissolution of the nucleus pulposus in humans. JAMA. 1964;187:137-140.

Steinbach HL. The roentgen appearance of osteoporosis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1964;2:191-207.

Thompson GH. Back pain in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:928-938.

Turner PG, Green JH, Galasko CS. Back pain in childhood. Spine. 1989;14:812-814.

Vaccaro AR, Martyak GG, Madigan L. Adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. Orthopedics. 2001;24:1172-1177.

Waldenstrom J. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. New York: Grune & Stratton Inc, 1970.

Wedgwood RJ, Schaller JG. The pediatric arthritides. Hosp Pract. 1977;12:95-97. 83–589–90

Weinerman SA, Bockman RS. Medical therapy of osteoporosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1990;21:109-124.

Wheeler M. Osteoporosis. Med Clin North Am. 1976;60:1213-1224.