The autonomic nervous system

Anatomy and physiology

The autonomic nervous system controls important functions that are not under voluntary control, that is autonomous. The extent of this autonomy varies; initiation of swallowing or micturition is voluntary and subsequent execution is automatic, but there is no voluntary component to gastrointestinal motility. As well as descending control from the CNS, some autonomic structures may function independently, and under humoral control. For example, the heart has an intrinsic pacemaker in the sinoatrial node, which may be modulated by circulating adrenaline (epinephrine) and by sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve inputs.

Peripheral autonomic nerves

The peripheral nerves of the autonomic nervous system are small unmyelinated fibres. Afferent autonomic fibres are contained in many peripheral nerves. The spectrum of diseases that affects them overlaps with, but is different from, that affecting unmyelinated fibres in peripheral neuropathies (pp. 102–105)

Causes of autonomic dysfunction

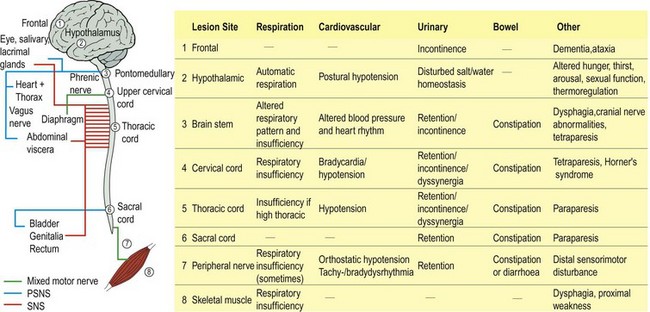

Lesions at all levels of the nervous system may affect autonomic function (Fig. 1) and the site of the lesion determines the pattern of involvement as well as associated deficits. Most autonomic disturbances are acquired but there are some rare inherited causes, for example certain inherited neuropathies. Some common neuropathies particularly affect autonomic function, especially those due to diabetes mellitus or alcohol. The autonomic nervous system is also affected by many widely used medications, especially antihypertensive agents.

Clinical manifestations of autonomic disturbance

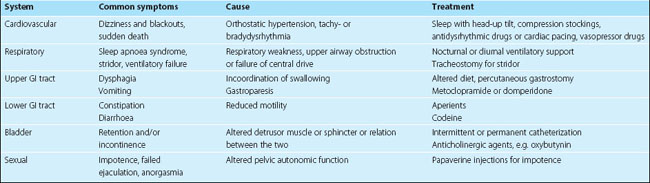

Autonomic disturbance may affect just one system, for example cardiovascular, or it may be more generalized. Clinically important consequences affect respiration, swallowing, cardiovascular, bowel, bladder and sexual function (Table 1). Rarely, failure of sweating can result in dangerous hyperpyrexia. There are three main categories of autonomic dysfunction:

Investigation of autonomic failure

The first step is confirmation of autonomic dysfunction. Simple clinical tests are described in Table 2. More sophisticated autonomic responses can be measured in a specialized laboratory. These may be supplemented by tests for cause (Table 3), neuroimaging for CNS disease and nerve conduction studies for peripheral disease.

| What to do | What it means |

|---|---|

| Heart rate response to standing up from supine. Measure ratio of longest R–R interval (30th beat) to shortest R–R interval (15th beat) |

PSNS denervation – constriction

Table 3 Causes of autonomic failure

| Central | Peripheral | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | ||

| Chronic |

Treatment and prognosis

Treatments for different symptoms of autonomic disturbance are outlined in Table 1. Treatment may also be addressed to the cause, for example diabetes mellitus. There is no specific treatment for primary autonomic failure or multisystem atrophy.