CHAPTER 44 The Asian rhinoplasty

Introduction

Asian rhinoplasty is distinguished from other ethnic groups based on differences in anatomy, individual aesthetic goals, and surgical technique. Anatomical features of Asians include thicker skin, weaker cartilages, less dorsal projection, rounder tip and alae, and a more retrusive columella.1,2 Asian patients seeking rhinoplasty typically present with the chief complaint of a flat, wide nose and bulbous tip. Their aesthetic goals are to raise the dorsum, to increase tip projection, and refine the tip contours while still maintaining their ethnic appearance.

Surgical techniques, aimed at strengthening and augmenting the weaker cartilage framework, have supplanted traditional reductive techniques described for the over-projected Caucasian nose.3 Controversy over an ideal technique has divided practitioners, principally based upon material preference: alloplastic implants versus autogenous grafts. The most common material used worldwide is currently silicone alloplast formed as either an L-shaped implant to augment both the dorsum and support the columella or a straight (I-shaped) dorsal onlay implant. Other alloplastic materials include expanded polytetrafluoroethylene [ePTFE] (Surgiform Technology, Ltd., Columbia, South Carolina) and porous high density polyethylene, Medpor® (Porex Corp., Newnan, Georgia). Autogenous tissue options have included cartilage (septal cartilage, auricular cartilage, costal) and bone (split-calvarium, iliac crest, olecron, costal) sources.1,4,5 The senior author’s preferred method is costal cartilage because of its abundant availability, mechanical strength, and resistance to infection, resorption or extrusion.

Physical evaluation

Anatomy

Deep to this layer is the nasal skeleton of bone and cartilage. The bony dorsum, which makes up the superior third of the nose, is comprised of paired nasal bones attached to the frontal process of the maxillary bones laterally and the nasal process of the frontal bones superiorly. The inferior two-thirds of the nasal skeleton is cartilaginous, including the septum, paired upper lateral, lower lateral, and sesamoid cartilages. The quadrangular cartilaginous septum connects with the anterior bony skeleton through the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone superiorly, the vomer bone posteriorly, and the maxillary crest inferiorly. Supporting the dorsum lateral to the septum are the upper lateral cartilages, which attach to the undersurface of the nasal bones superiorly, the pyriform aperture laterally, and are continuous with the cartilaginous quadrangular septum medially. The inferior edge of the upper lateral cartilages join the lower lateral cartilages in the “scroll area” caudally. The lower lateral cartilages are paired arches that join medially by fibrous connections within the columella. Connections also exist between the medial crura and caudal cartilaginous septum.

Consideration of the entire face must not be ignored when evaluating a patient for rhinoplasty. The nose is the central feature of the face; and thus, should be reshaped in harmony with the overall facial dimensions and contours. The anatomic aesthetic subunits of the nose include the median structures (dorsum, tip, and columella) and paired lateral structures (nasal side walls, alae, and soft triangle facets). In contrast to Caucasians, Asians typically do not have a well-demarcated soft tissue triangle or nasal sill, and the lower dorsal profile tends to blend the sidewall into the cheek.6 Other differences include a lower lying radix, greater alar width, and more extreme nasolabial angles. The nasolabial angle is more obtuse in Asian females, but more acute in Asian males compared to Caucasians.7 The overall structural support in the Asian nose is weaker when compared to Caucasians. The lower lateral cartilages are weaker and the quadrangular cartilage is both thinner and smaller. Thus, septal cartilage alone as a source for augmentation grafting material is typically inadequate.

Technical steps

Cartilage harvest

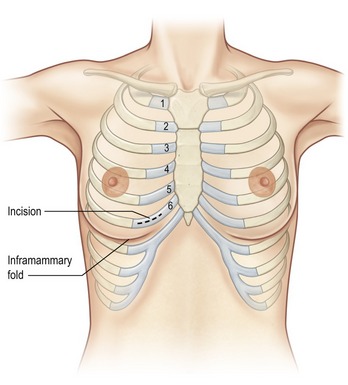

Costal cartilage harvest typically precedes the nasal surgery in order to maintain sterility and decrease the possibility of cross-contamination from the nose to the chest. Several choices exist when harvesting costal cartilage. Cadaveric studies have advocated harvesting the seventh rib as an ideal choice because of its superior length, greater thickness, and its location inferior to the lung pleura and lateral to the course of the internal mammary artery.8 The senior author prefers the sixth rib due to its close proximity to the inframammary crease (Fig. 44.1). Sometimes both sixth and seventh ribs are harvested through a single common incision when a large amount of grafting material is required (e.g. grafts for dorsal and premaxillary augmentation). The fifth rib has the benefit of fewer connections to neighboring ribs, but it tends to be more curved and shorter than the sixth rib. Selection of the rib is thus case specific and depends upon accessibility, presence of calcifications, volume of graft required, and rib configuration.

Preoperatively, a thorough history should include questions about previous chest surgery, breast augmentation, and type of breast implants if present. In the female patient, breast size can limit the surgeon’s ability to adequately expose the more superiorly situated ribs. Access is further complicated by the presence of implants that both increase the breast size and require a more inferior dissection path in order to avoid entering the implant capsule.

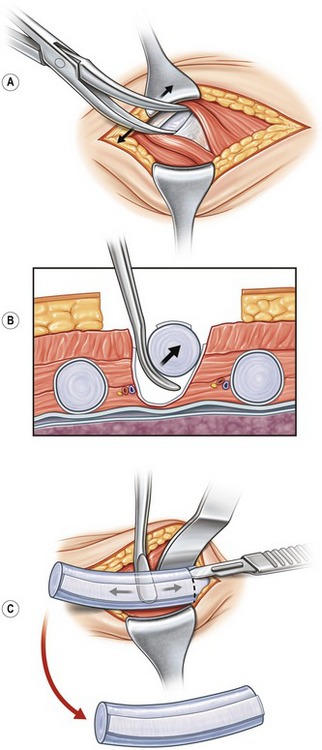

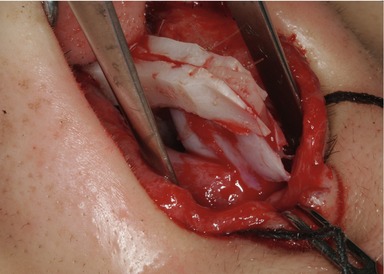

The harvesting procedure begins with the skin incision and sharp dissection through subcutaneous adipose and breast tissue down to the pectoralis muscle fascia. The fascia is sharply divided and the muscle fibers are bluntly spread using a hemostat (Fig. 44.2A). Blunt dissection with a cotton dissector clears the remaining soft tissue off the rib to expose the perichondrial surface. The osseous junction is confirmed using a 27-gauge needle, and this landmark marks the lateral most extent of the useful costal cartilage. The perichondrium is incised along the osseochondral junction and along the superior and inferior edge of the anterior surface of the rib to create a “window” through the perichondrium to the cartilage below. The strip of perichondrium within this window is elevated with a Freer elevator, excised in a 5–8 cm length, and stored in sterile saline for later use. Next, the rib is dissected away from the remaining perichondrium circumferentially, taking care to avoid injury to the deep perichondrium, which intimately overlies the lung pleura (Fig. 44.2B). An incision is made halfway through the rib just medial to the osseochondral junction. A medial incision is also made based on the length of cartilage required for the augmentation (Fig. 44.2C). A blunt-tipped Freer elevator is used to complete the cartilage incisions and dissect through the neighboring rib costal attachments. This isolates the dissected segment of costal cartilage, which is removed and set aside in sterile saline to soak. Attention is then directed to the medial and lateral margins of the in-situ rib. A rongeur is used to bevel the sharp edges, which prevents potential visibility or edge palpability. Irrigation solution is then instilled into the surgical bed and the anesthesiologist is asked to perform a Valsalva maneuver. If there were any openings into the pleural space, bubbles in the irrigation fluid would indicate an air leak. Closure of the wound is deferred until the end of the procedure in case additional rib or perichondrium is needed. The wound is lightly packed with a moistened cotton gauze and covered to maintain sterility.

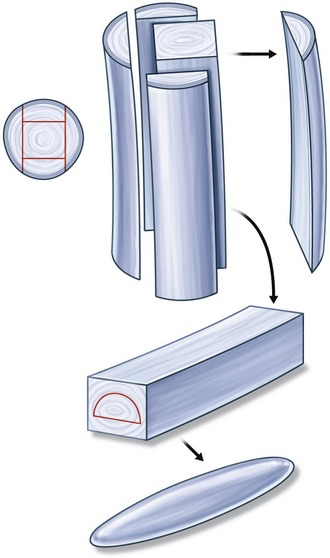

The most technically challenging aspect of augmentation rhinoplasty using costal cartilage is carving the grafts. Costal cartilage must be carved sequentially, over several hours, with frequent soaking periods to allow the natural warping tendencies of each piece to be declared. The dorsal graft must have minimal warping, and is best carved from the central core of the rib.9,10 (Fig. 44.3).

Stabilization of the nasal base

For patients who require increased nasal length, changes to tip rotation, and alteration to the columella–ala relationship, but do not require premaxillary augmentation, the caudal extension graft is the preferred method.11 This graft is also placed between the medial crura but is placed end to end or overlaps with the caudal septum and is fixed directly to the caudal septum with a 5-0 PDS mattress suture. Placement of the graft can correct nostril asymmetry by placing the graft on the side of the larger nostril to reduce its size. The surgeon can customize the shape and placement of the graft in order to control changes to nasal length, columella position and tip rotation. Figure 44.4 illustrates the counter-rotation affect of a graft that is longer along the superior margin; whereas Fig. 44.5 demonstrates the increased rotation created by a graft with a longer inferior margin. Graft dimensions are highly variable depending on the desired affective change; however, at least 3 to 4 mm of graft should overlap with the septum to achieve adequate base stability. Additional stability and major nasal lengthening can be achieved with the use of extended spreader grafts fixed directly to the caudal extension graft placed end to end (Fig. 44.6). The medial crura are sutured to the caudal edge of the caudal extension graft with 4-0 plain gut on a straight septal needle.

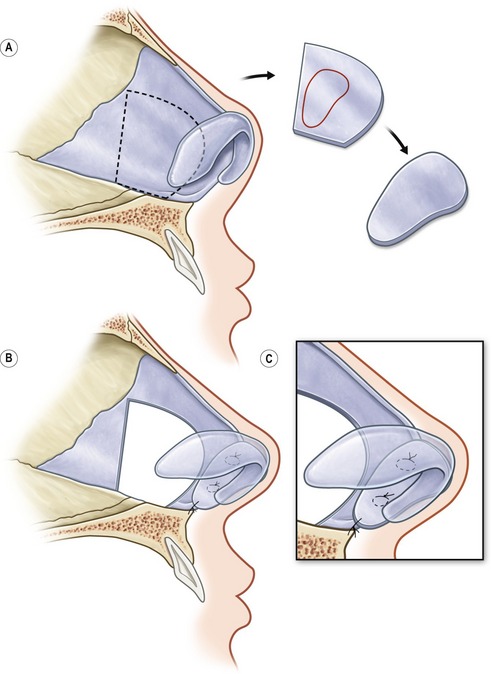

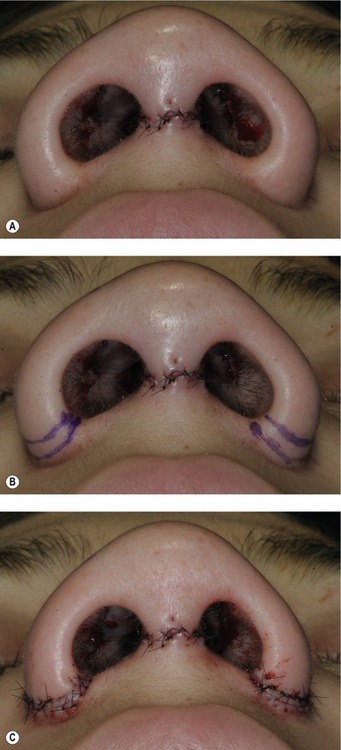

Fig. 44.5 A–C, To increase tip rotation and blunt the nasolabial angle, the caudal extension graft should be longer along the inferior margin.

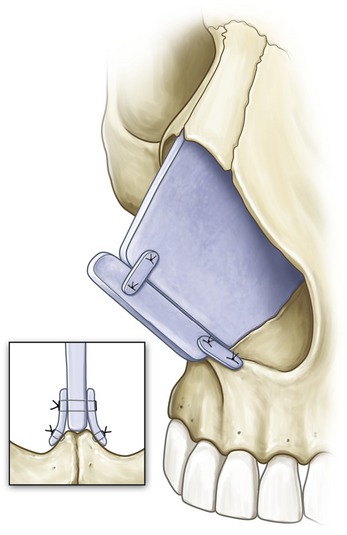

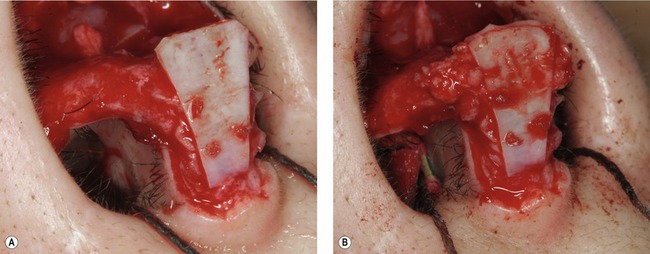

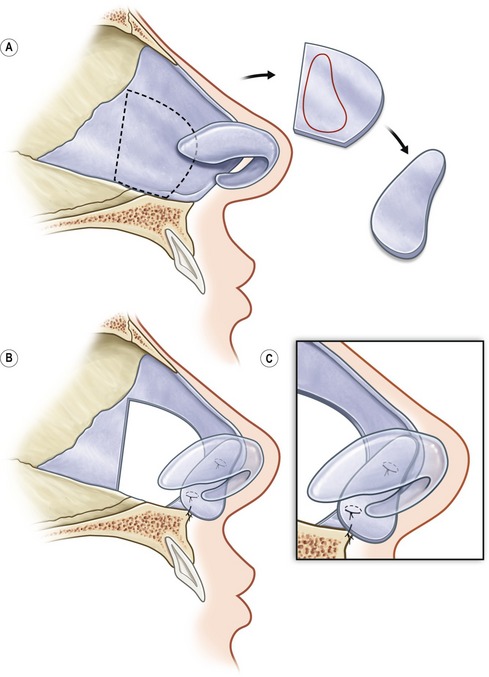

Patients who require augmentation of the premaxilla need more complex tip support methods. The extended columellar strut can be used with a premaxillary graft for maximal premaxillary augmentation, or without the premaxillary graft for modest premaxillary augmentation. When the extended columellar strut is placed without a premaxillary graft, it is placed in a pocket between the medial crura and fixed directly to the nasal spine via two possible techniques. First, it can be sutured to thin splinting grafts placed bilaterally, which are in turn sutured to the nasal spine through a predrilled hole using a 16-gauge needle (Fig. 44.7). Alternatively, a notch can be created through the nasal spine with a 5 mm osteotome, and the extended columellar strut can be slotted into the notch and fixed with two 4-0 PDS sutures tied directly to the bone through a similarly predrilled hole (Fig. 44.8A–D). The amount of premaxilla augmentation is directly proportional to the degree of caudal extension of the extended columella graft that extends caudal to the nasal spine. The nasal length and columella-ala relationship are also controlled by the caudal extension of the graft. Rotation of the tip can be precisely controlled by altering the angle of the graft prior to securing the anterior projection to extended spreader grafts from above. Tip projection is determined by graft length, and columellar thickness on base view is directly proportional to graft thickness. The extended columella graft is a powerful technique that also enables the surgeon to correct deviations of the nasal base from midline. When the nasal spine does not align with a vertical line dropped down from the nasion, the extended columella graft can be placed left or right of the nasal spine to correct for this deviation. The combination of an extended columella graft and premaxillary graft is useful to maximize augmentation of the premaxilla. The premaxillary graft is placed, depending on its size, either through the medial intercrural pocket or a separate sublabial incision. It is sutured directly to the nasal spine with suture either through periosteum or the pre-drilled hole. A notch carved on the anterior surface of the premaxillary graft supports the extended columellar graft (Fig. 44.9).

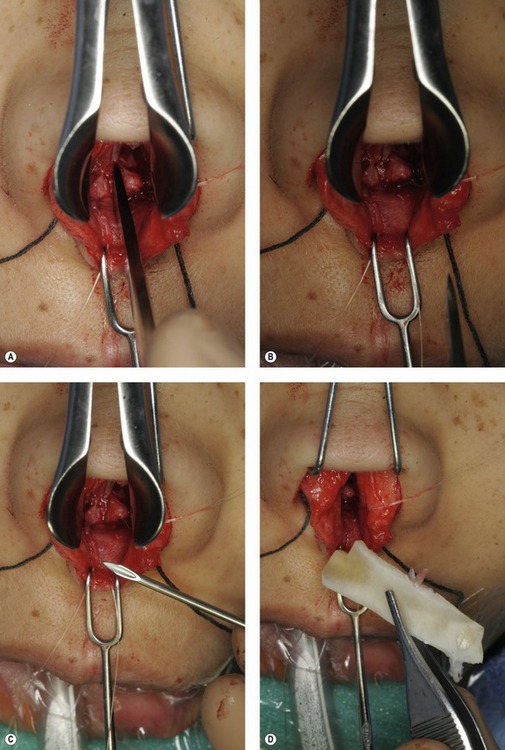

Fig. 44.8 The extended columellar strut can also be fixed to the nasal spine by creating a notch in the nasal spine and setting the graft inside the notch. A, A 5 mm osteotome is used to create a notch in the nasal spine. B, The notch is made at the center of the nasal spine so each splayed half of bony spine serves as a splint for the graft. C, A 16-gauge need is used to drill a hole through the nasal spine posterior to the notch. D, The extended columellar strut is carved with a corner cut out to create a groove. This groove secures the graft once placed in the notch to prevent anterior or posterior movement of the graft.

Nasal tip contouring

After setting the base, the tip can be shaped through a variety of tip contouring techniques. The surgeon’s choice of method to project the tip should meet the patient’s aesthetic goals while suiting their anatomical limitations.

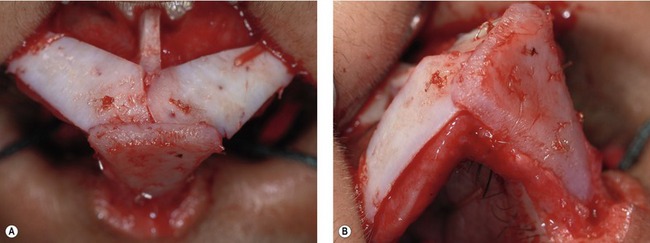

The tip shield graft can project into thick skin, creating favorable nasal tip contours. A tip shield graft is most effective with a slight convexity and placement above the dome by at least 2 mm. The edges are beveled and the graft is sutured to the caudal margin of the medial crura with at least four 6-0 Monacryl sutures. The top edge of the graft is camouflaged to prevent visibility in the future. If the top of the graft is between 2 and 3 mm above the dome it can be camouflaged with a buttress graft sutured immediately behind the graft (Fig. 44.10A,B). The cephalic trim cartilage can be used as the buttress graft and sutured just behind the leading edge of the shield graft. The buttress graft should extend laterally a millimeter or two beyond the shield graft to provide adequate camouflage.12 When additional projection is needed and the graft projects more than 3 mm above the existing domes, lateral crural grafts should be sutured to the posterior surface of the graft (Fig. 44.11A,B). These grafts are carved and sutured so that they are at 45 degrees to the back surface of the tip graft, creating a smooth transition between the graft and the lateral crura. Flat pieces of cartilage create the best tip contour. These grafts also provide structural support to the tip, preventing cephalic rotation of the shield graft, and should be of adequate strength. The lateral crural grafts are sutured to the lateral crura with 6-0 Monacryl sutures. Further camouflage can be achieved with a strip of perichondrium. This tissue is sutured over the leading edge of the shield graft with 6-0 Monacryl in a horizontal orientation (Fig. 44.12). This additional tissue adds tip projection and creates a more rounded tip, which is ideal for the Asian patient.

Dorsal augmentation

The key to successful use of costal cartilage lies in the carving technique. Preparing costal cartilage for use as a dorsal graft requires sequential modifications over several hours of soaking in antibiotic solution between carvings. The warping tendency of each piece of cartilage declares itself over time, and the sequential carving modifications can utilize the natural bending in an advantageous configuration. Dorsal grafts become problematic when visible irregularities are seen through the skin. This can occur when the graft shifts, the edges curl up from the dorsal foundation to tent up the skin, or the entire graft bends left or right of midline. It is imperative to carve the dorsal graft sequentially in order to orient the block of cartilage with the bending surface facing down on the dorsum and the lateral edges aligned straight and parallel. A canoe-shaped graft takes form with the concave surface oriented against the nasal dorsum, the sides parallel to each other and straight, the convex surface up against the skin, the cephalic end contoured to a narrower tip, and all edges appropriately beveled with rounded edges. This configuration creates an anatomically correct brow-tip aesthetic line and decreases the chance of unwanted bending since the bending tendency of the cartilage is resisted by the tension of the overlying skin cover against the graft and dorsum. Graft edge camouflage is further enhanced by the placement of a perichondrium cover over the graft such that the edges of the perichondrium extend beyond the graft edges, much like a tablecloth drapes over a table. When the use of perichondrium is anticipated, the added thickness of the perichondrium should be accounted for when carving the appropriate thickness of the costal cartilage.

The caudal end of the graft can be customized to individual patient needs. If a patient needs major tip support, significant counter rotation, or extra lengthening, the dorsal graft can be integrated into an extended columellar strut by notching the dorsal graft’s caudal edge (Fig. 44.13). This creates a reliable and structurally sound way of controlling nasal length, tip rotation, and projection in conjunction with the aforementioned tip stabilization techniques. The combination of grafting maneuvers in the tip and dorsum enables the surgeon to significantly modify nasal contours (Figs 44.14 and 44.15).

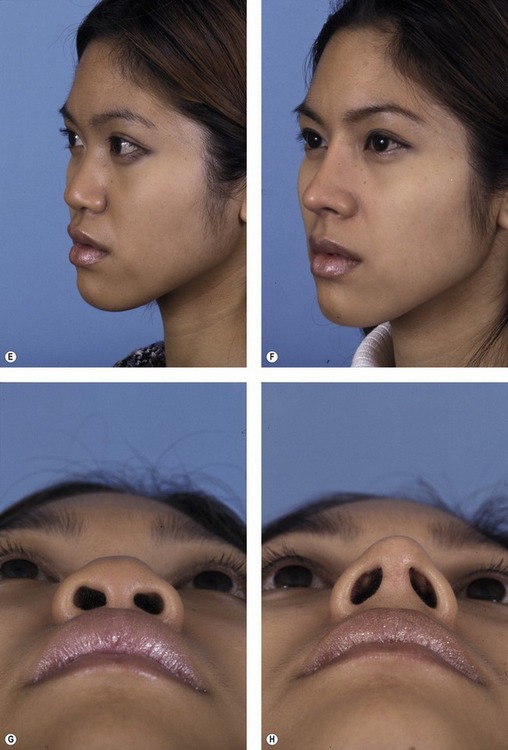

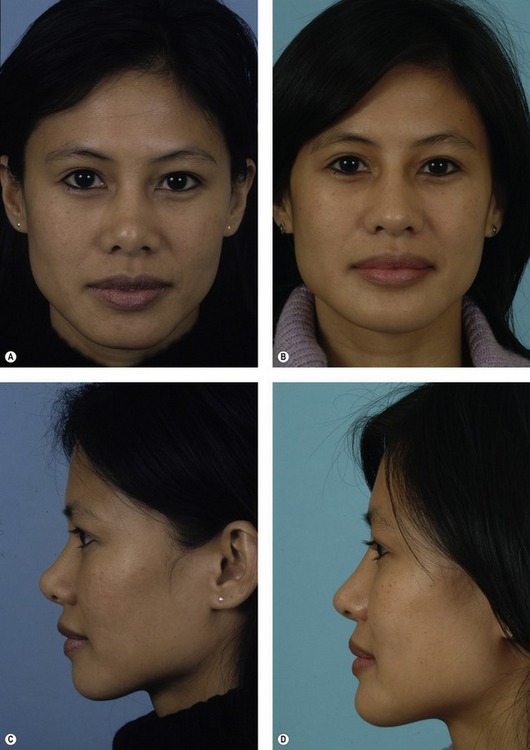

Fig. 44.14 A patient who had a silicone L-shaped implant that extruded through her nasal tip leaving a tip scar. Reconstruction was accomplished using costal cartilage extended columellar strut, premaxillary graft, and dorsal graft. The extended columellar strut was integrated into a notch in the caudal margin of the dorsal graft. A, C, E and G, Preoperative views. B, D, F, and H, Postoperative views.

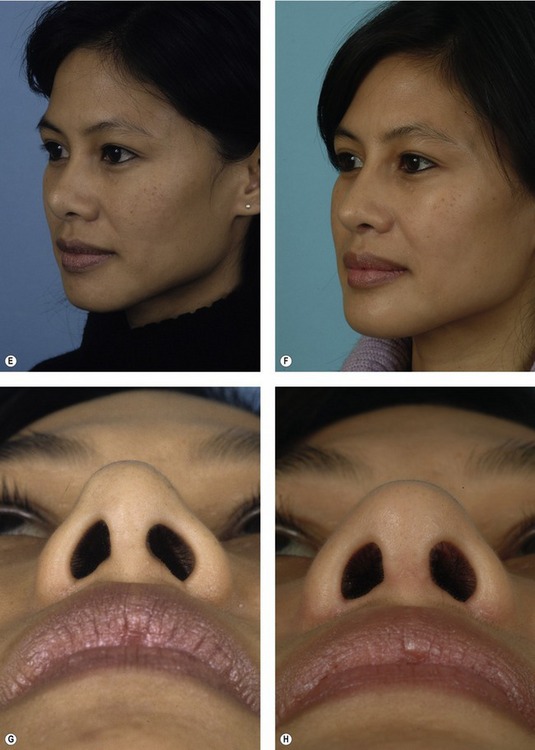

Fig. 44.15 This patient had a shortened, upturned nose after previous rhinoplasty. Costal cartilage was harvested to create a caudal extension graft secured to two extended spreader grafts to increase nasal length. Lateral crural strut grafts were used to lower the retracted nostrils. The nasal dorsum was augmented with a septal cartilage dorsal graft. A, C, E and G, Preoperative views. B, D, F and H, Postoperative views.

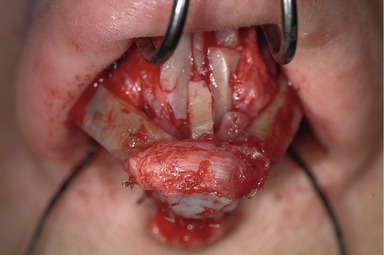

Wound closure

Alar base reduction is indicated when the alar base width is excessive as determined on base view. A favorably beveled incision is planned to excise a conservative ellipse of excess alar skin to appropriately narrow the base. The ellipse extends through the lateral nostril sills (when nostril diameter requires reduction) or is limited to the lateral ala skin 2 to 3 mm superior to alar crease (when nostril diameter is appropriate). Primary closure with interrupted vertical mattress 7-0 black nylon sutures completes the procedure (Fig. 44.16).

Postoperative care

Nearly all patients are discharged the same day from the ambulatory surgery center. Postoperative care, beginning in the recovery unit, is centered on patient comfort. Effort is made to reduce pain, swelling and chances of bleeding and infection. The patient is prescribed acetaminophen–hydrocodone analgesics once tolerating oral intake, ice packs to the glabellar region hourly, a nasal drip pad to work synergistically with the intranasal dressing for hemostasis, and prophylactic antibiotics. The patient is instructed to avoid nose blowing, straining activity, overheating, eating excessive sodium, manipulating or wetting the nasal cast dressing. The patient should sleep with slight head elevation and perform deep breathing exercises through the mouth. The first follow-up visit occurs in 24 hours after surgery to remove intranasal dressings and stents. Proper wound care is instructed and medications are reviewed. The patient is seen again on postoperative day seven to remove the cast, sutures and lateral wall splints. Follow-up appointments are frequent (1 to 3 week intervals) over the first three months when intervention is most effective to deal with graft shifting or warping. The patient is an active participant in nasal compression exercises to guide the positioning of the healing cartilages. Edema is expected, but can be tempered through a combination of compression exercises, low sodium diet, taping and judicious use of subdermally injected triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog, 10 mg/mL) in aliquots of 0.2 mL. Injection is more frequently indicated with very thick skin-types. Caution against intradermal injection should be stressed to prevent skin atrophy and long-term contour irregularities. Follow-up care is encouraged for many years. The patients are forewarned and continually reminded that edema resolves slowly and tip definition will continue to improve over months to years with soft tissue scar contracture.

Complications

Complications of costal cartilage harvest

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Extra time should be spent discussing the proposed outcome with the patient using computer imaging. Parameters such as dorsal height, tip projection, nasal length and width should be discussed.

• When augmenting the nasal dorsum lateral osteotomies should be avoided. It is preferable to keep a wide dorsum to act as a base for the dorsal graft. If the bony dorsum is narrowed then an unnatural, tubular appearing dorsum can be created.

• Costal cartilage must be carved sequentially to allow observation of tendencies toward bending. It is preferable to use a dorsal graft that has some curvature with the concavity oriented against the dorsum.

• The nasal base should be stabilized to avoid postoperative loss of tip projection. As tip projection is increased the tip will tend to rotate cephalically. Extended spreader grafts combined with an extension graft can preserve nasal length.

• When using tip grafts, camouflage is critical to avoid graft visibility or an overly sharp nasal tip.

Pitfalls

• Inadequate structure resulting in postoperative loss of tip projection or shortening of the nose giving an over-rotated appearance.

• Creation of an overly high nasal starting point that will look unnatural in an Asian patient. The nasal starting point in an Asian patient should be at the level of the midpupillary line.

• Asian patients typically have a rounder nasal tip. This rounder tip contour should be preserved and excessive narrowing should be avoided.

• Use of alloplastic implants in the nasal tip can be problematic. The nasal tip is mobile and is not a good location for alloplastic implants as they tend to become infected, extrude or thin the nasal tip skin.

• Alar base reduction can leave unsightly scarring if not placed properly or closed precisely. Alar base reduction should be very conservative in the Asian patient as most Asian patients have a wider nasal base.

Summary of steps

1. Inframammary incision in right chest to harvest medial costal cartilage from rib number 5, 6, or 7.

2. Cartilage carving to create necessary supportive and contouring grafts.

3. External rhinoplasty approach to expose nasal skeleton using sharp dissection in the sub-SMAS plane of the soft tissue envelope.

4. Base stabilization with either a caudal septal extension graft, caudal septal replacement graft or extended columella graft constructed from costal cartilage is secured to the maxillary spine.

5. Placement of extended spreader grafts bilaterally with fixation to the caudal septal graft or columella graft to establish tip rotation.

6. Lateral nasal wall support using a combination of techniques that may include alar battens, lateral crural struts, lateral crural repositioning, and/or suture suspension of the upper lateral cartilages.

7. Tip contouring with appropriate placement of tip shield grafts, tip cap grafts, tip buttress grafts, lateral crural grafts, rim grafts, and/or perichondrium soft tissue camouflage.

8. Establishment of nasal starting point and dorsal height with dorsal costal cartilage onlay graft sutured down to extended spreader grafts and covered with camouflaging perichondrium.

9. Wound closure using interrupted vertical mattress 7-0 black nylon sutures to the columella skin, 6-0 fast absorbing gut suture to the vertical columella incision, and 5-0 chromic suture to the vestibular skin of the marginal incisions.

10. Base reduction of flaring ala with favorable beveled incisions.

1. Ahn JM. The current trend in augmentation rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2006;22(1):61–69.

2. Han SK, Lee DG, Kim JB, et al. An anatomic study of nasal tip supporting structures. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(2):134–149.

3. Mao GY, Yang SL, Zheng JH, et al. Aesthetic rhinoplasty of the Asian nasal tip: a brief review. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32(4):632–637.

4. Peled ZM, Warren AG, Johnston P, et al. The use of alloplastic materials in rhinoplasty surgery: a meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):85e–92e.

5. Hodgkinson DJ. The Eurasian nose: aesthetic principles and techniques for augmentation of the Asian nose with autogenous grafting. Aesth Plast Surg. 2007;31:28.

6. Yotsuyanagi T, Yamashita K, Urushidate S, et al. Nasal reconstruction based on aesthetic subunits in Orientals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(1):36–44.

7. Leong SCL, White PS. A comparison of aesthetic proportions between the Oriental and Caucasian nose. Clin Otolaryngol. 2004;29:672–676.

8. Jung DH, Choi SH, Moon HJ, et al. A cadaveric analysis of the ideal costal cartilage graft for Asian rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(2):545–550.

9. Gibson T, Davis WB. The distortion of autogenous cartilage grafts: its cause and prevention. Br J Plast Surg. 1957;10:257–274.

10. Kim DW, Shah AR, Toriumi DM. Concentric and eccentric carved costal cartilage: a comparison of warping. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8(1):42–46.

11. Toriumi DM. Caudal septal extension graft for correction of the retracted columella. Operative Techniques. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;6(4):311–318.

12. Toriumi DM. New concepts in nasal tip contouring. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8:156–185.