17 The anorectum

Applied surgical anatomy

Anal musculature and innervation

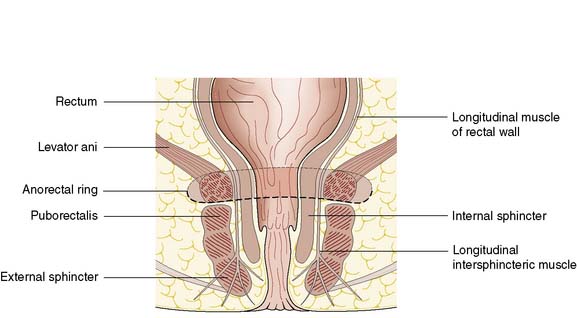

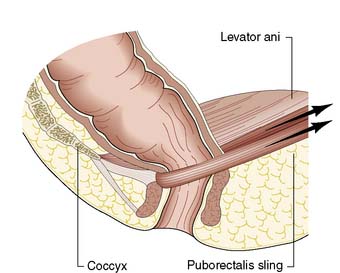

The anal canal is 3–4 cm long in males and slightly shorter in females. It consists of two concentric muscle layers known as the internal and external sphincters (Fig. 17.1). The internal sphincter is a condensation of the circular smooth muscle of the rectum and is a continuation of the circular muscle of the gastrointestinal tract. It is controlled by the autonomic nervous system with fibres from the pelvic sympathetic nerves, the lower lumbar ganglia and the pre-aortic/inferior mesenteric plexus. Parasympathetic fibres arise from the sacral plexus. The smooth muscle of the internal sphincter maintains tone and contributes to resting pressure within the anal canal, so playing an important role in maintaining continence. The longitudinal muscle of the gut ends at the anus as a series of fibrous bands that radiate to the perianal skin, and is of little consequence to perianal disease. The striated muscle of the external sphincter is under voluntary control, being innervated bilaterally by the internal pudendal nerves and the fourth branch of the sacral plexus. The circular muscle tube of the external sphincter blends with the lower part of the levator ani, known as the puborectalis sling (Fig. 17.2). The puborectalis fibres of the levator ani originate from the posterior aspect of the pubic symphysis and pass posteriorly to join the external sphincter. The levator ani muscles themselves are also important in maintaining the relationship of the anus and rectum during defaecation.

Anal canal epithelium

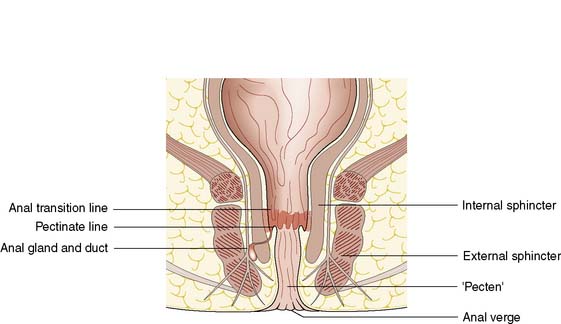

The cell type of the anal canal epithelium determines why certain diseases, such as tumours and viral infections, affect only particular levels of the canal. The epithelium of the anal canal is specialized and contains three distinct zones. The external zone (from dentate line to anal verge) is keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium. There is a short, modified, anal transitional zone of non-keratinized squamous epithelium, which lies immediately proximal to the dentate line, separated from the columnar epithelial of the anal canal but continuous with the rectal epithelium. The anal valves are crescentic mucosal folds that form a serrated or dentate line on the luminal aspect of the mid-anal canal (Fig. 17.3). The dentate line represents the line of fusion between the endoderm of the embryonic hindgut and the ectoderm of the anal pit. Thus, the epithelium is innervated by the autonomic nervous system and is insensate with respect to somatic sensation. The canal lining below the dentate line is innervated by the peripheral nervous system and so conditions affecting this region, such as abscess, anal fissure or tumour, result in anal pain.

There are 4–8 specialized anal glands located within the substance of the internal sphincter or in the space between the internal and external sphincters at the level of the mid-anal canal; these glands have ducts that open directly on to the dentate line (Fig. 17.4). They are involved in the aetiology of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano. The function of the anal glands is to secrete mucus, lubricating and protecting the delicate epithelium of the anal transition zone. The ducts from these glands open into the folds of mucosa at the dentate line. The relevance of these glands lies in the fact that they are the source of most perianal abscesses. When an anal gland duct becomes occluded, the obstructed gland may become infected with gut organisms such as coliforms, and anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides.

Anorectal disorders

Haemorrhoids

Clinical features

Management

Non-operative approaches

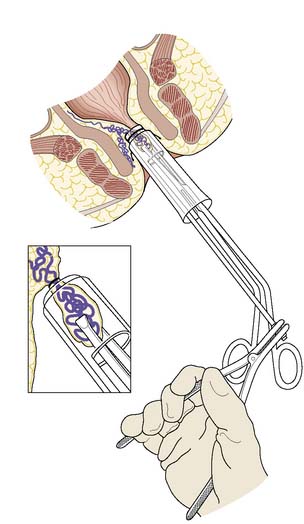

There are many non-operative approaches to the treatment of haemorrhoids, the aim of which is to cause fibrosis and shrinkage of the protruding haemorrhoidal cushion in order to prevent bleeding and prolapse. Current outpatient clinic treatment approaches include application of small rubber bands to strangulate the pile (using a special Barron’s bander); submucosal injection of sclerosant; and the application of heat by infrared photocoagulation. There is no strong evidence that any of these approaches is much better than doing nothing at all. In the long term, the symptoms of untreated piles tend to wax and wane, and the recurrence of symptoms after any of these procedures is much the same as without any treatment. However, of all the non-operative treatments, rubber band ligation (Fig. 17.6) may be the most effective in the short term. Where there is a significant cutaneous component to the piles, any of the outpatient treatments is likely to be painful because of the cutaneous nerve supply, and is also unlikely to succeed. In these circumstances, the decision should be to do nothing but reassure the patient, or to offer an operation.

Operative approaches

The principle of haemorrhoidectomy involves total removal of the haemorrhoidal mass and securing of haemostasis of the feeding vessel. The wound can be left open or can be closed, but there are rarely problems with healing or infection. In some cases, there are secondary haemorrhoids between the main right anterior, right posterior and left lateral positions, and these are also removed as part of the operation. Recently, a different surgical approach using a circular stapler has been developed, the stapled anopexy. This technique aims to divide the mucosa and haemorrhoidal cushions above the dentate line in order to transect the feeding vessels and hitch up the stretched supporting fibroelastic tissue, rather than removing the whole haemorrhoidal mass as in the standard haemorrhoidectomy. Stapled haemorrhoidectomy may have a place for the treatment of symptomatic first- and second-degree piles (EBM 17.1). With all surgical approaches to treating

17.1 Haemorrhoids

Summary Box 17.3 Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoids are common and best treated conservatively.

• First-degree: visible in the lumen on proctoscopy but do not prolapse

• Second-degree: prolapse on defaecation but return spontaneously

• Third-degree: remain prolapsed but can be replaced digitally

• Fourth-degree: long-standing prolapse and cannot be replaced in the anal canal.

• First-degree: advice on avoiding constipation and straining

• Second-degree: conservative management, banding, injection sclerotherapy, haemorrhoidectomy

• Third-degree: if symptomatic, haemorrhoidectomy

• Fourth-degree: thrombosed piles are usually treated conservatively in the first instance; interval haemorrhoidectomy may not be required.

piles, it is important to consider that the haemorrhoidal cushions contribute to fine control of continence. Hence, an element of anal incontinence can be one of the long-term sequelae of any haemorrhoidectomy. Surgery should not be considered lightly.

Fissure-in-ano

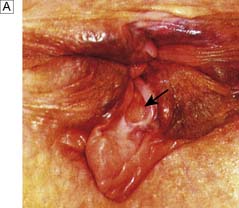

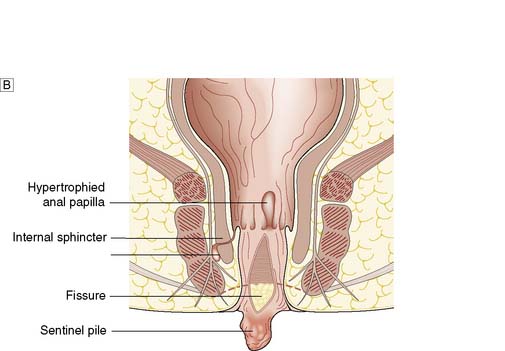

Fissure-in-ano is a common condition characterized by a linear anal ulcer, often with the internal sphincter visible in the base, affecting the anal canal below the dentate line from the anal transition zone to the anal verge (Fig. 17.7). There is often little in the way of granulation tissue in the ulcer base. Owing to failed attempts at healing, there may be a tag of skin at the lowermost extent of the fissure, known as a ‘sentinel pile’. At the proximal extent of the fissure there may be a hypertrophied anal papilla. Sometimes fissures will heal incompletely and mucosa will bridge the edges of the fissure. This results in a low perianal fistula and may present years later. Fissures are most frequently observed in the posterior midline of the anal canal, although anterior fissures may occur in women following childbirth; they are rarely seen in males.

Clinical features and diagnosis

The diagnosis should be suspected from the history alone and is confirmed by gently parting the superficial part of the anal sphincter with the gloved fingers to reveal the characteristic linear ulcer. There may be an associated ‘sentinel pile’, which consists of heaped-up skin at the lowermost extent of the linear ulcer (Fig. 17.7). It is often too painful to perform a digital rectal examination or a proctoscopy, and so this is best left until after treatment is instigated. However, it is important to complete clinical assessment with rigid sigmoidoscopy at a later date. A full history is important to exclude previous perianal surgery, perianal abscess, trauma during childbirth or symptoms consistent with Crohn’s disease.

Management

Until the relatively recent advent of chemical sphincterotomy as first-line treatment, surgery was the only option. Surgery still has a major role in the management of patients who have fissures resistant to medical treatment, or who have recurrence. Anal stretching has been abandoned, as it is associated with significant sphincter damage and the risk of incontinence (EBM 17.2). Lateral sphincterotomy is the most common operation for anal fissure and involves controlled division of the lower half of the internal sphincter at the lateral position (3 o’clock or 9 o’clock with the patient in the lithotomy position). There is a small but appreciable risk of late anal incontinence following lateral sphincterotomy. This is usually only to gas, but occasionally faecal incontinence to liquid or solid can occur, particularly in women who have had birth-related anal sphincter damage. In women, it may therefore be more appropriate to avoid further division of any sphincter muscle, and this can be achieved using an anal advancement flap or a rotation flap to cover the ulcerated base of the fissure and allow new, well-vascularized skin to heal the ulcer and reduce the associated anal spasm.

Perianal abscess

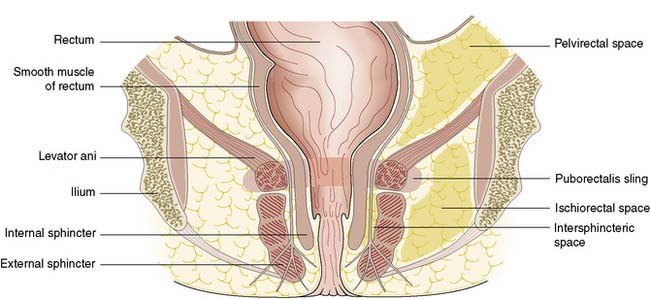

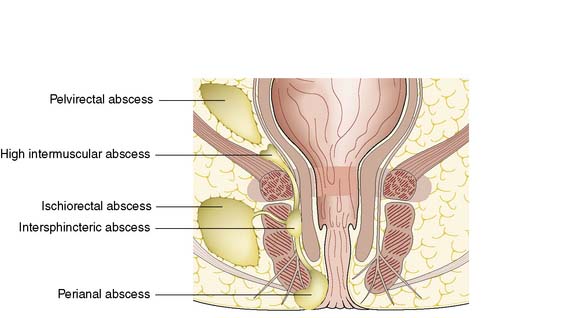

Perianal abscess is a nonspecific term encompassing abscesses in the perianal, intersphincteric, ischiorectal or pelvirectal spaces (Fig. 17.8). Perianal suppuration is common, affecting men three times more frequently than women.

Fig. 17.8 Spread of infection from the anal gland to the anorectal spaces and resultant abscess formation.

Summary Box 17.4 Anal fissure

Pain on defaecation and outlet type bleeding are the cardinal symptoms

Typically affects younger age groups (18–30 years)

In older age groups, Crohn’s disease or cancer should be suspected.

Conditions that predispose to perianal abscess include Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, as well as any cause of immunosuppression such as haematological disease, diabetes mellitus, chemotherapy and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Most patients who present with perianal abscess have no predisposing factors and most abscesses are cryptoglandular, initiated by blockage of the anal gland ducts (see Fig. 17.3). The obstructed anal gland becomes secondarily infected with large bowel organisms such as Bacteroides, Streptococcus faecalis and coliforms. The fact that the anal glands are situated in the intersphincteric space (see Fig. 17.4) explains the routes that the infection may take as pus tracks along the line of least resistance through the tissue spaces. Rarely, patients with established sepsis elsewhere may develop metastatic suppuration in the perianal region.

Clinical features

In cases where the abscess remains localized within the intersphincteric space, the patient presents with acute anal pain and tenderness. There is usually no evidence of suppuration on inspection of the perianal region. Pain often prevents digital examination, and so general anaesthetic is required. The main differential diagnosis is acute anal fissure. The diagnosis is confirmed by demonstration of a localized pea-sized lump in the intersphincteric space. True perianal abscess is the most common type, in which pus tracks inferiorly to appear at the perianal margin between the internal and external sphincters (Fig. 17.8). Symptoms are usually of 2–3 days’ duration and the abscess may have discharged spontaneously. Systemic upset is minimal and anal pain is the predominant presenting complaint.

Fistula-in-ano

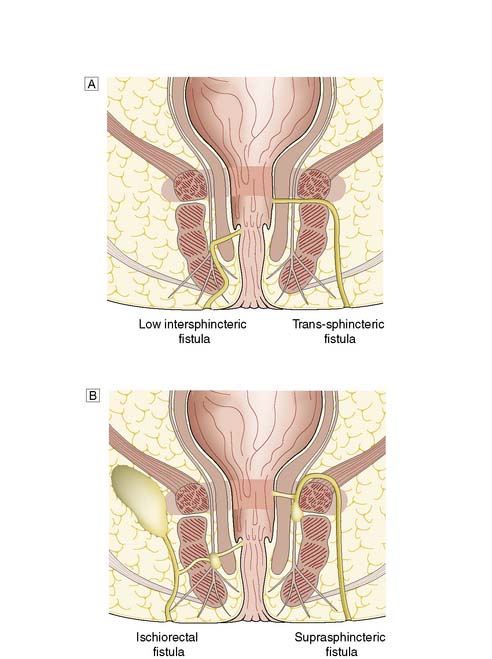

The underlying pathogenesis of the vast majority of cases of perianal abscess or anal fistula is obstruction of the anal gland duct. This results in stasis and infection of the anal gland (cryptoglandular infection). Abscess precedes all such cases of fistula, although the sepsis is often subclinical. Inappropriate surgical drainage of perianal abscess is responsible for a small but significant proportion of fistulae. Figure 17.9 is a simplified diagram showing the classification of fistula-in-ano. A fistulous tract should be suspected in all patients with recurrent perianal abscess. Typically the patient presents repeatedly with an abscess that intermittently points and discharges pus on to the perianal skin. However, there is no need to search routinely for a fistula when draining straightforward perianal abscesses. Inexpert probing may inadvertently induce a fistula.

Fig. 17.9 Categories of fistula-in-ano.

A Low intersphincteric and trans-sphinteric. B Ischiorectal and suprasphincteric.

Clinical features and assessment

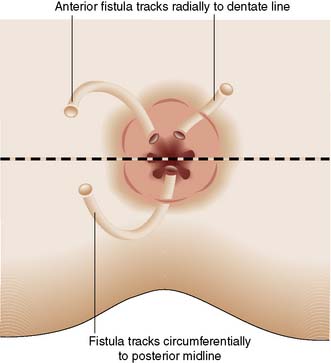

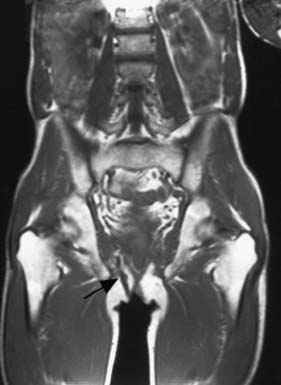

In most cases, the patient presents with a chronically discharging opening in the perianal skin, associated with pruritus and perianal discomfort. A detailed clinical history is essential to determine any predisposing medical conditions or previous surgery. Investigation requires examination under anaesthetic (EUA) by a colorectal specialist when the fistula should be probed to trace the tract from external to the internal openings. Goodsall’s Law is a rough rule of thumb as to the likely course of fistulous tracts. Thus, when the fistula opens on the perianal skin of the anterior anus, the tract usually passes radially directly to the anal canal. However, when the opening is posterior to a line drawn between the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions (Fig. 17.10), then the tract usually passes circumferentially backwards and enters the anal canal in the midline (6 o’clock position). It is essential to avoid inducing further fistulae by ill-advised probing of the region. It is important to determine whether the fistula is low or high (Fig. 17.9), as the prognosis and treatment are different for each. Most fistulae can be delineated and treated at EUA, but complex cases may merit magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI of a complex high fistula involving the pelvirectal space is shown in Figure 17.11. Endoanal ultrasound may be useful. Further investigation to exclude Crohn’s disease may be appropriate, involving colonoscopy, small bowel MRI or small bowel follow-through.

Management

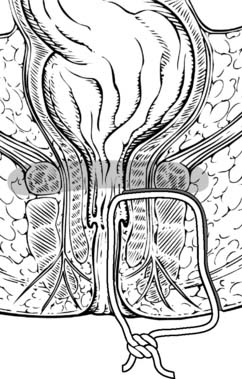

Treatment is determined by the course of the fistula tract. Usually, low fistulae can simply be laid open and allowed to heal. However, where a significant proportion of the internal and/or external sphincter is involved, then laying open the tract will result in faecal incontinence. In such complex cases, the fistula tract can be probed and a seton passed along its length (Fig. 17.12) to allow the fistula to drain. Once it is drained, a tighter seton can be applied that will gradually cut out through the sphincters, allowing them to heal behind the seton. Applying such a cutting seton maintains the ends of the sphincters together and minimizes the risk of incontinence. High fistulae may be treated by an anorectal advancement flap. This involves raising a flap of rectal wall and upper internal sphincter. The flap is advanced distally to close the internal opening. The external opening and superficial part of the tract heals as there is no faecal stream to maintain the sepsis. In some complex cases, a defunctioning colostomy may be necessary.

Miscellaneous benign perianal lumps

Anal cancer

There is a strong association between anal cancer and infection with HPV types 16 and 18. HPV infection is responsible for the majority of anal carcinomas. Smoking is a risk factor and likely interacts with viral infection. Anogenital warts are also a risk factor, as is anoreceptive intercourse. HIV infection is also a predisposing factor, owing to im-munosuppression and susceptibility to viral infection. The premalignant lesion, anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN), is probably the precursor of most anal carcinomas and is analogous to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), the precursor lesion of cervical cancer. The level of AIN (1–3) is dependent on the degree of cytological atypia and the depth of that atypia in the epidermis. A high proportion of AIN 3 progresses to carcinoma and is shown in Figure 17.13. It is important to perform a cervical smear in patients with proven anal cancer. There is also an association with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), which also has a common HPV aetiology.

Clinical features and assessment

Anal cancer is frequently misdiagnosed in the early stages because of its rarity and because symptoms of benign anal conditions are highly prevalent. Early cancer may be confused with fissures, piles and warts. Nevertheless, because of accessibility, anal tumours are readily detectable by careful clinical examination; anal pain/discomfort, bleeding or discharge into the underwear, and pruritus ani should be sought. Advanced tumours that have spread to the anal sphincters may present with incontinence. Clinical examination of anal cancer at the margin reveals an ulcerated discoid lesion at the anal verge (Fig. 17.14). Cancer of the anal canal may not be visible, although extensive lesions may protrude to the anal verge by direct spread. Careful examination under anaesthetic is required to allow tumour biopsy and sigmoidoscopy. Biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis, but also to determine the tissue of origin, as the treatment for squamous carcinoma varies from that for adenocarcinoma.

Staging

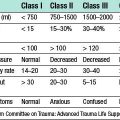

Staging is important for prognosis and also guides treatment approaches. The TNM staging system for anal cancer is shown in Table 17.1. The lymph nodes most commonly involved are the inguinal groups, particularly for anal verge cancers. Canal tumours may spread proximally to the mesorectal nodes or to the internal iliac nodes via the middle rectal lymph nodes. Lymphadenopathy alone is not sufficient to confirm lymph node spread, and accessible nodes should be biopsied because reactive changes due to infection are common. Examination under anaesthetic is an important part of clinical staging, as the tumour is often painful and the anus tender to digital examination. CT and MRI are essential; endoanal ultrasound may be helpful but usually needs to be performed under anaesthetic.

| T (Tumour) |

• NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

• N0 No regional lymph node metastasis

• N1 Metastasis in perirectal lymph node(s)

• N2 Metastasis in unilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal lymph node(s)

• N3 Metastasis in perirectal and inguinal lymph nodes and/or bilateral internal iliac and/or inguinal lymph nodes

Management

For early, well-circumscribed superficial (T1N0) carcinomas, wide surgical excision is the optimal treatment, as it avoids the morbidity of chemoradiotherapy. However, for T2, T3 and T4 tumours, treatment comprises radiotherapy to the anal canal and inguinal lymph nodes, combined with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (recently capecitabine is preferred) and mitomycin C (EBM 17.3). Newer regimens of radiotherapy, combined with capecitabine and cisplatinum, are also being introduced. The usual approach is external beam radiotherapy, but radioactive implants such as selectron wires are also used in selected cases. Surgery has a limited role in the primary treatment of these lesions but does play an important part in the management of advanced disease. Surgery is reserved for radiotherapy treatment failures, when ‘salvage’ abdominoperineal excision of the anus and rectum may afford a cure in some cases and alleviate symptoms in others.

17.3 Anal cancer

Summary Box 17.7 Anal carcinoma

• Anal carcinoma is associated with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18

• Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is a malignant precursor

• Local surgical excision is the treatment of choice for T1N0 lesions

• Chemoradiotherapy is treatment of choice for T2, T3, or T4 lesions

• Chemoradiotherapy is mandatory for those with involved lymph nodes

• Abdominoperineal resection is reserved for failures of chemoradiation.

Rectal prolapse

• A full-thickness rectal prolapse (procidentia) includes the mucosa and the muscular layers.

• Mucosal prolapse, as the name suggests, involves only the mucosal lining of the rectum.

• Occult rectal prolapse refers to intussusception of the rectal wall but without the prolapse protruding through the anal canal. This term also refers to the much rarer condition of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. This consists of a prolapse of the full thickness of the anterior rectal wall only, although the terms occult rectal prolapse and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome are not synonymous.

The pathological process that results in rectal prolapse is incompletely understood. However, certain factors are clearly implicated in predisposing to the condition. Mucosal prolapse should not be confused with full-thickness prolapse. It is often associated with a degree of haemorrhoids, but whether these are causal or simply the result of a common aetiology is not understood. The majority of cases of full-thickness rectal prolapse occur in elderly women, with no obvious aetiological basis. Weight loss in the elderly with loss of fat supporting the rectum, combined with degeneration of collagen fibres and weakness of the musculature of the pelvic floor, results in loss of the anorectal angle and laxity of the rectal wall (see Fig. 17.2). In many cases, there is a deep rectovaginal pouch with a long loop of sigmoid colon that pushes down into the rectovaginal pouch and contributes to the prolapse. Occasionally, there is a clear history of obstetric injury but most patients are nulliparous.

Clinical features and assessment

Examination confirms the diagnosis in most cases. If the prolapse is not apparent, it will usually appear when the patient strains on a commode. A typical example of a full-thickness rectal prolapse is shown in Figure 17.15. Digital examination reveals a patulous anus, poor sphincter tone and evidence of a weak pelvic floor on straining. Rigid sigmoidoscopy will reveal cases of occult prolapse. If the history is of short duration, consideration should be given to the presence of a spinal tumour, a spinal stenosis or a prolapsed intervertebral disc. In occult rectal prolapse, radiological assessment using a defaecating proctogram or dynamic MRI may help secure the diagnosis. Conditions that might be mistaken for a rectal prolapse include large fourth-degree haemorrhoids, prolapsing rectal neoplasia, anal warts, anal skin tags and fibroepithelial anal polyp. On the basis of symptoms alone, the differential diagnosis of rectal prolapse includes rectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease, and these should be excluded by appropriate investigations.

Management

Full-thickness rectal prolapse

• Perineal approaches aim to fixate or excise the prolapse surgically from below. ‘Delorme’s procedure’ involves the excision of the mucosa lining the prolapse, with plication of the muscle tube, and ‘perineal rectosigmoidectomy’ entails excision through the anus of the prolapsed rectum and lower part of the sigmoid. The latter may be combined with a repair of the pelvic floor (Altmeier procedure)

• Abdominal approaches aim to fix the rectum to the bony pelvis using sutures or foreign material. Increasingly these procedures are performed laparoscopically. The abdominal approach may also include resection of the redundant sigmoid colon, particularly when constipation is a predominant feature, because rectal fixation usually aggravates the constipation.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

Summary Box 17.8 Rectal prolapse

Anal incontinence

Faecal incontinence is both distressing and socially disabling, but patients are often reluctant to discuss the issue with relatives or with medical professionals due to social stigma and embarrassment. Hence, the population prevalence of incontinence is probably underestimated. Nevertheless, it has been variously estimated at 2–5% in the general population and 10% of adult females. There are a variety of specific aetiological factors but the majority of cases are ‘idiopathic’, most commonly affecting older parous women. Aetiological factors associated with anal incontinence are listed in Table 17.2.

| Trauma |

Clinical features and assessment

A full history is essential, with particular reference to obstetric history and any past perianal operations. Incontinence should be graded using established scoring systems, such as the Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score, which incorporate frequency and severity of episodes of incontinence to gas, liquid or solid stool. Such scores enable more objective assessment of any improvement or deterioration in incontinence. Coexisting disease should be documented and neurological symptoms sought. A defaecation history should be sought, including the degree of defaecatory urgency. It is important to enquire about co-existing urinary incontinence. Examination to determine sphincter tone, the presence of previous scars and the state of the rectovaginal septum should be undertaken. Poor anal sensation suggests a neurogenic basis for the incontinence. Other anorectal causes of incontinence, as listed in Table 17.2, should be excluded where possible, and by rigid sigmoidoscopy in all cases. It is important to remember that any cause of intestinal hurry (such as colonic cancer, inflammatory bowel disease or even infective diarrhoea) can render incontinent a patient who had previously been coping with a more formed stool. Hence, colonoscopy is an important part of assessment. Endoanal ultrasound scanning of the sphincters delineates the presence and extent of any sphincter defect. Anorectal physiology studies document resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures, and also define whether there is a predominant neurogenic element. Where there is any concern from the history or clinical examination regarding a spinal lesion, MRI should be performed.

Conservative management

Any remedial causes of incontinence (Table 17.2) should be addressed appropriately. However, women with ‘idiopathic’ faecal incontinence constitute the majority of cases. In older women, who almost universally have a combination of sphincter and nerve damage, conservative measures should be instigated in the first instance. Dietary advice is important to avoid exacerbating factors in the diet, such as caffeine, spicy foods and excessive alcohol. Stool-bulking agents such as Fybogel should be combined with loperamide to reduce the propulsive activity of the GI tract and induce a degree of constipation. In cases with a predominant neurogenic basis, rectal irritability resulting in faecal urgency may respond to therapy with amitriptyline (25–50 mg at night). Conservative measures should be combined with regular emptying of the rectum using stimulant suppositories or enemas. In many cases, these measures have a dramatic beneficial effect on quality of life even when minor degrees of incontinence persist.

Surgical management

Summary Box 17.9 Faecal incontinence

• Faecal incontinence is most common in females

• Childbirth injury is a common aetiological factor

• Associated with neurological disorders, trauma and perianal sepsis or surgery.

• Most respond well to conservative management

• Stool bulking, antidiarrhoeal agents such as loperamide

• Enemas may be required to maintain the rectum free of faeces

• Surgery reserved for debilitating incontinence after failed conservative management:

sphincter repair – excellent results for (rare) discrete sphincter injury, poor for majority

Pilonidal disease

Pilonidal disease is a common perianal disorder with a population incidence of 20–30 per 100 000. It is characterized by chronic inflammation in one or more sinuses in the midline of the natal cleft that contain hair and debris (Fig. 17.16). The superficial part of the midline sinus is lined with squamous epithelium, but the tracts themselves are lined with granulation tissue resulting from chronic infection. Pilonidal disease can also affect the digital clefts in hairdressers but this is not discussed here.