12 The acute abdomen and intestinal obstruction

Aetiology

The causes of the acute abdomen may be subdivided into surgical, medical and gynaecological disorders. Surgical causes may be classified according to the organ involved, as well as the underlying pathological process (Table 12.1). The most common causes in any population will vary according to age, sex and race, as well as genetic and environmental factors (Tables 12.2 & 12.3).

| Surgical Inflammation |

Cardiovascular

Table 12.2 Common causes of acute abdominal pain in UK adults requiring admission to hospital

| Condition | Approximate incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Non-specific abdominal pain | 35 |

| Acute appendicitis | 30 |

| Acute cholecystitis and biliary colic | 10 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 5 |

| Small bowel obstruction | 5 |

| Gynaecological disorders | 5 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 2 |

| Renal and ureteric colic | 2 |

| Malignant disease | 2 |

| Acute diverticulitis | 2 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 |

| Miscellaneous | 1 |

Table 12.3 Common causes of acute abdominal pain in UK children

Pathophysiology of abdominal pain

Somatic pain

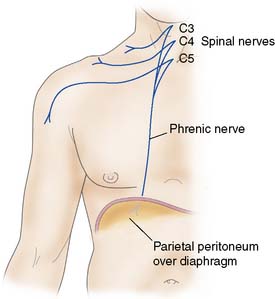

When the diaphragmatic portion of the parietal peritoneum is irritated peripherally, there will be pain, tenderness and rigidity in the distribution of the lower spinal nerves, but when it is irritated centrally, pain is referred to the cutaneous distribution of C3, 4 and 5 (i.e. the shoulder area, Fig. 12.1). Somatic pain is classically described as sharp or knife-like in nature, and is usually well localized to the affected area.

Visceral pain

Summary Box 12.1 Abdominal pain

• Visceral abdominal pain is mediated by the sympathetic nervous system and is typically deep-seated and ill localized to the area originally occupied by the viscus during intrauterine life

• Colic is a form of visceral pain that arises from a hollow viscus with muscle in its walls (e.g. gut, gallbladder, ureter), and results from excessive muscle contraction, often against an obstructing agent

• Patients experiencing colic are usually unable to remain still during the bout of pain but are pain-free between attacks. ‘Biliary colic’ is an exception (and the term colic may be a misnomer), in that pain often waxes and wanes on a plateau and there are no pain-free intervals

• Parietal pain, such as that caused by parietal peritonitis, is mediated by somatic nerves and is localized to the area of inflammation

• Reflex guarding and rigidity of the overlying muscles is usually present, and the patient is reluctant to move for fear of exacerbating the pain

• Some areas of the peritoneum (e.g. the pelvis, posterior abdominal wall) are ‘non-demonstrative’ in that parietal peritonitis may be present without tenderness or guarding of overlying muscles.

Pathogenesis

As one can see from the list of surgical conditions that may present with acute abdominal pain (Table 12.1), there are two main underlying pathological processes involved: inflammation and obstruction. These processes may be triggered by a variety of underlying abnormalities. It is important to realize that in any one patient a combination of abnormalities and processes may be involved.

Peritonitis

Inflammation of the peritoneum (peritonitis) may be classified according to extent (either localized or generalized) and aetiology (Table 12.5). In a surgical setting, the most common cause of generalized peritonitis is perforation of an intra-abdominal viscus. Inflammation of the peritoneum results in an increase in its blood supply and local oedema formation. There is transudation of fluid into the peritoneal cavity, followed by the accumulation of a protein-rich fibrinous exudate. In the normal state, the greater omentum constantly alters its position within the abdominal cavity as a result of intestinal peristalsis and abdominal muscle contraction. In the presence of inflammation, the greater omentum will adhere to and surround the abnormal organ. The fibrinous exudate effectively glues the omentum to the inflamed viscus, walling it off and preventing the further spread of inflammation. In addition, the exudate inhibits intestinal peristalsis, resulting in a paralytic ileus which also limits the spread of the inflammation and infection. As a result of the ileus, fluid accumulates within the lumen of the intestine and, along with the formation of large volumes of intra-peritoneal transudate and exudate, this will lead to a decrease in the intravascular volume, producing the clinical features of hypovolaemia.

| Generalized peritonitis |

|---|

| Primary: infection of the peritoneal fluid without intra-abdominal disease |

| Localized peritonitis |

|---|

Infarction

An infarct is an area of ischaemic necrosis caused either by an occlusion of the arterial supply or the venous drainage in a particular tissue, or by a generalized hypoperfusion in the context of shock (Table 12.6). The typical histological feature of infarction is ischaemic coagulative necrosis. An inflammatory response begins to develop along the margins of an infarct within a few hours, stimulated by the presence of the necrotic tissue.

| Occlusive |

| Arterial |

Perforation

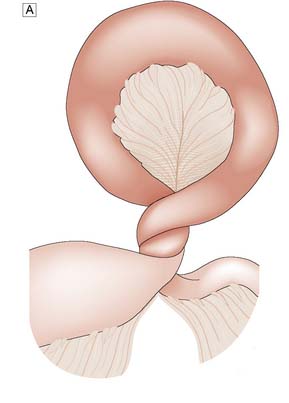

Spontaneous perforation of an intra-abdominal viscus may be the result of a range of pathological processes. Weakening of the wall of the viscus, which might follow degeneration, inflammation, infection or ischaemia, will predispose to perforation. An increase in the intraluminal pressure of a viscus, such as occurs in a closed-loop obstruction (Fig. 12.2), will predispose to perforation, as will peptic ulceration, acute appendicitis and acute diverticulitis. Other less common causes are carcinoma of the colon, inflammatory bowel disease and acute cholecystitis.

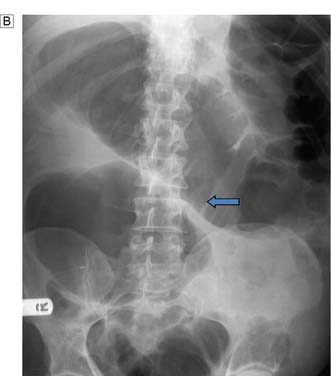

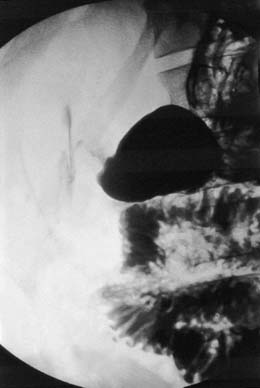

Fig. 12.2 Volvulus: an example of closed-loop obstruction.

A Diagrammatic representation of a volvulus. B X-ray showing volvulus of sigmoid colon.

Clinical assessment

History

The main presenting complaint of patients with an acute abdomen is pain. The characteristics of the pain (Table 12.7) give important clues to the likely underlying diagnosis, and these should be explored in depth. However, the importance of a full history cannot be overemphasized and is essential in all patients.

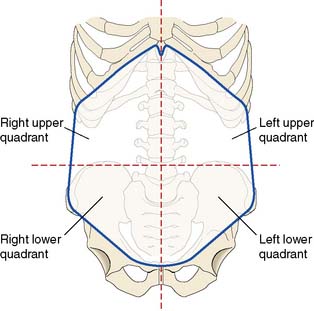

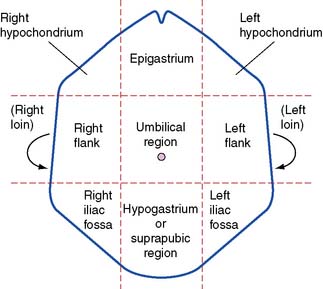

Site of pain

The site of abdominal pain is perhaps the most valuable pointer to the underlying diagnosis. In order to describe the site of pain, the abdomen is traditionally divided into either quarters or ninths (Figs 12.3 and 12.4).

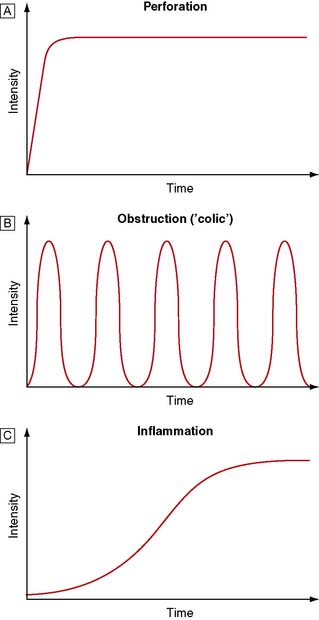

Onset of pain

The onset of pain can be sudden or gradual. Typically, pain from a perforation is sudden and that from inflammation is gradual. Patients with the former can usually remember exactly what they were doing at the time of onset, whereas in the latter localization in time is more difficult. The various characteristics of abdominal pain, as shown in Figure 12.5, are essential in helping the clinician formulate a differential diagnosis.

Examination

Other important features to look for on general examination include clinical evidence of anaemia, jaundice, cyanosis and dehydration. It is important to bear in mind that physical signs are often less obvious than might be expected in the elderly, the obese, the generally unwell and those taking steroids. As in every emergency patient, a full examination, including the cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological systems, in addition to the abdomen and pelvis, must be carried out and the results documented. Specific details relating to the abdominal examination are described below and in Table 12.8.

| Method | Question | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | What is the abdominal contour? | Distension: intestinal obstruction or ascites |

| Does the abdomen move with respiration? | Rigid abdomen: peritonitis | |

| Can the patient blow out/suck in the abdomen? | Rigid abdomen: peritonitis | |

| Does the patient lie still or writhe about? | Fear of movement: peritonitis Writhes about: colic |

|

| Are there visible abnormalities? | Scars: relevant previous illness, adhesions Hernia: intestinal obstruction Visible peristalsis: intestinal obstruction Visible masses: relevant pathology |

|

| Gentle palpation | Is there tenderness, guarding or rigidity? | Tenderness/guarding: inflamed parietal peritoneum Rigidity: peritonitis |

| Deep palpation | Are there abnormal masses/palpable organs? | Palpable organs/masses: relevant pathology |

| Is there rebound tenderness? | Rebound tenderness: peritonitis | |

| Percussion | Is the percussion note abnormal? | Resonance: intestinal obstruction |

| Loss of liver dullness: gastrointestinal | ||

| perforation | ||

| Dullness: free fluid, full bladder | ||

| Shifting dullness: free fluid | ||

| Auscultation | Are bowel sounds present/abnormal? | Absent sounds: paralytic ileus Hyperactive sounds: mechanical obstruction, gastroenteritis |

| Is there a bruit? | Bruit: vascular disease | |

| Do not forget to: | ||

| Examine the groin | ||

| Consider a digital rectal examination | ||

| Consider a vaginal examination when appropriate | ||

| Examine the chest | ||

Inspection of the abdomen

Palpation

Palpation of the abdomen should be carried out in a systematic manner, beginning with gentle superficial examination of the whole abdomen looking for tenderness. This should start away from the site of maximum pain and move towards the tender site, encompassing all areas, as shown in Figures 12.3 and 12.4. Palpation over an area of tenderness will cause pain, which in turn will stimulate the patient to contract the overlying muscles (voluntary guarding). If the pain is due to inflammation, the approximation of the parietal peritoneum on to the inflammatory area will result in a reflex contraction of the overlying muscles (involuntary guarding). If the whole peritoneal cavity is inflamed, then there will be generalized peritonitis and the abdominal wall will be rigid (board-like rigidity). When the palpating hand, which has been pushing the parietal peritoneum against the inflamed viscus, is suddenly released, the viscus will bounce back and hit the parietal peritoneum, causing an additional sharp pain (rebound tenderness). This is an excellent indication of underlying peritoneal inflammation (peritonism) but is very painful and is better tested by light percussion. As already mentioned earlier, history of pain on coughing or moving is also a good indication of peritoneal inflammation.

Investigations

Blood tests

Serum amylase

A serum amylase greater than three times the upper limit of normal is highly suggestive of acute pancreatitis. Lesser values are non-specific and can be the result of a wide range of conditions. However, as many as 20% of patients with acute pancreatitis may have normal amylase levels on admission. Other causes of a raised amylase are shown in Table 12.9. In patients with acute pancreatitis who present more than 48 hours after the onset of pain, the serum amylase may have returned to normal. In these patients, measurement of the urinary amylase may be of value.

| Pancreatic conditions |

Liver function tests

Liver function tests are increasingly becoming available on an emergency rather than a routine basis in many hospitals, as clinicians have recognized their value in the assessment and subsequent management of acute hepatobiliary and pancreatic disorders (see chapter 14). The measurement of gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) is a particularly sensitive test for possible stones in the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis).

Radiological investigations

Plain X-rays

The role of plain radiography in the investigation of the patient with acute abdominal pain has been well studied. The erect chest X-ray (CXR) is the most appropriate investigation for the detection of free intra-peritoneal gas (Fig. 12.6) and should be carried out in any patient who might have a perforation. If the condition of the patient prevents an erect film being taken, then a left lateral abdominal decubitus film might be helpful. Although a visceral perforation is the most common cause of free intra-peritoneal gas, other causes exist and should be considered where appropriate (Table 12.10). An erect CXR is also useful in identifying a respiratory condition which may present with upper abdominal pain.

Fig. 12.6 Gas under the diaphragm seen on the erect chest X-ray in a patient with a perforated peptic ulcer.

Table 12.10 Causes of free subdiaphragmatic gas on abdominal X-ray

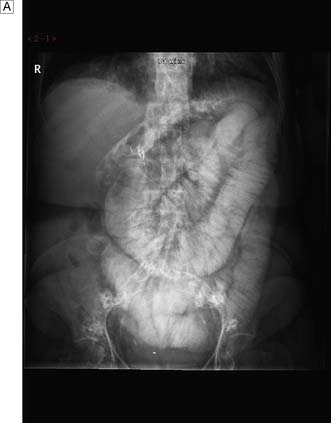

The role of plain abdominal radiographs remains controversial despite many studies that have demonstrated that, with the exception of suspected intestinal obstruction (Fig. 12.7), they rarely help in the diagnosis and have even less role in altering the clinical decision (EBM 12.1). However, the supine abdominal X-ray (AXR) can be of use in patients whose diagnosis is unclear and in whom the presence of calcification (e.g. ureteric colic) and abnormal gas shadows (e.g. possible intestinal ischaemia) may be helpful. They should however not be performed routinely, and have no role in the investigation of patients with suspected appendicitis.

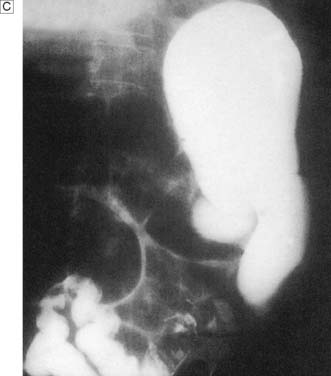

Contrast radiology

In up to 50% of patients with a perforated peptic ulcer, no free gas can be identified on plain radiography. If the diagnosis remains uncertain based on clinical assessment, a water-soluble contrast meal might be diagnostic (Fig. 12.8). In patients with small bowel obstruction, a water-soluble small bowel follow-up can help not only in confirming or refuting obstruction, but also in predicting which patient is likely to require surgery. Failure of contrast to reach the caecum by 4 hours suggests obstruction and these patients will not usually settle with non-operative management (Fig. 12.9).

A water-soluble contrast enema used to be considered essential in the assessment of patients with large bowel obstruction in order to differentiate between pseudo-obstruction and an obstruction caused by a mechanical problem (Fig. 12.10). However computed tomography (CT) with rectal contrast is now more commonly performed (see Ch. 16). Carrying out an unnecessary operation on a patient with pseudo-obstruction is associated with a high morbidity and mortality and cannot be defended.

Endoscopic investigations

Flexible sigmoidoscopy is commonly performed on patients who present with an acute abdomen associated with rectal bleeding and in those patients with large bowel obstruction to evaluate the anorectum. Additional information can be obtained from a colonoscopy. Furthermore, a sigmoid volvulus can often be deflated by careful sigmoidoscopy (see chapter 16). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is used to investigate patients with acute upper abdominal pain in whom a perforated peptic ulcer has been excluded, as discussed above.

Peritoneal investigations

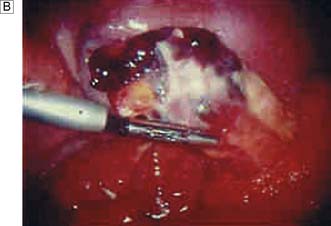

Laparoscopy

Many studies have demonstrated that laparoscopy (Fig. 12.11) can significantly improve surgical decision-making in patients with acute abdominal pain. It is particularly useful in patients for whom the decision to operate is in doubt, and in the elderly when findings from the history and examination can be misleading. Young women probably benefit the most from laparoscopy, as it is so difficult in this group to accurately differentiate acute appendicitis from acute gynaecological conditions, many of which do not require surgery. As laparoscopic appendicectomy increases in use, more patients will undergo diagnostic laparoscopy first.

Management

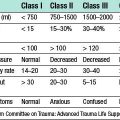

All patients admitted with acute abdominal pain require resuscitation and close monitoring, with regular re-evaluation. It is a good clinical rule that initial treatment should be based around the ABC principle (airway, breathing and circulation). Except in the management of overwhelming haemorrhage (e.g. ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and ruptured ectopic pregnancy) when resuscitation takes place on the way to the operating theatre, all patients with acute abdominal pain, including those requiring urgent surgery, benefit from adequate resuscitation. This will usually involve the administration of several litres of normal saline and/or a colloid solution, intravenous antibiotics and oxygen by face mask (see chapters 1 and 5). Monitoring by means of temperature, pulse, blood pressure, urine output and central venous pressure will depend on the clinical circumstances and will not be detailed further here. Suffice to say that good preoperative assessment, resuscitation, monitoring and regular reviewing of the patient with acute abdominal pain (initially every 30 minutes to 2 hours, depending on the state of the patient) is a prerequisite for a satisfactory clinical outcome. Indeed, following the first assessment, close observation and regular reassessment should be carried out on all patients without a definitive diagnosis, as their condition may well change and the underlying cause or the correct management may become more obvious. Until this time, it is common practice to keep the patient fasted; if there are signs or symptoms of obstruction, a nasogastric tube is inserted. Appropriate analgesia should be administered early to keep the patient as comfortable as possible. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis should also be commenced as a routine.

Peritonitis

Postoperative peritonitis

Intra-abdominal abscess

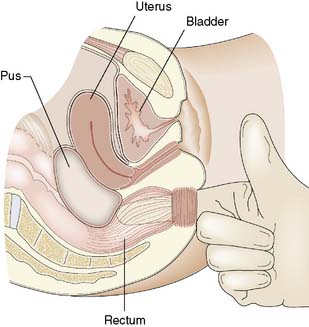

The site of the abscess may be suspected from the history and clinical examination, but localizing signs can be surprisingly few, particularly with subphrenic abscess, hence the expression ‘pus somewhere, pus nowhere else, pus under the diaphragm’. Unexplained fever after peritoneal infection or operation should always raise the suspicion of abscess formation. Tachycardia is usual. Pain and tenderness over the ribcage, shoulder-tip pain and a ‘sympathetic’ pleural effusion strengthen the suspicion of subphrenic abscess, whereas urgency of defaecation, diarrhoea and a boggy swelling in the pouch of Douglas on rectal examination are features of a pelvic abscess (Fig. 12.12).

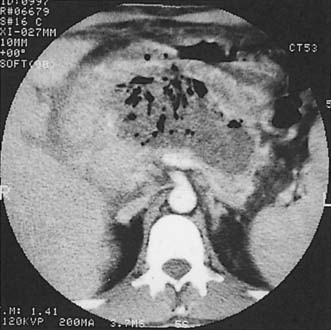

Ultrasound and/or CT are of immense value in diagnosis (Fig. 12.13), aspiration to obtain material for bacteriological culture and subsequent drainage. However, surgical drainage may still be needed to ensure effective drainage, particularly if the collection is loculated. Pelvic abscesses frequently rupture spontaneously into the rectum, but may require incision and drainage through the anterior rectal wall. Antibiotic therapy is used in conjunction with drainage of the abscess. Signs usually resolve rapidly following effective drainage.

Acute appendicitis

Anatomy

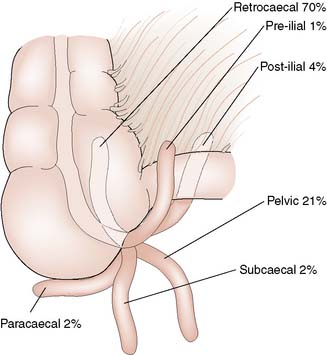

The appendix is a worm-shaped blind-ending tube that arises from the posteromedial wall of the caecum 2 cm below the ileocaecal valve. It varies in length from 2 to 25 cm, but is most commonly 6–9 cm long. On the external surface of the bowel, the base of the appendix is found at the point of convergence of the three taeniae coli of the caecum. On the surface of the abdomen, this point lies one-third of the way along a line drawn between the right anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus (McBurney’s point; Fig. 12.14). The appendix has its own mesentery, the mesoappendix, and its blood supply comes from the appendicular artery, a branch of the ileocolic artery. The position of the appendix is variable, depending on its length and mobility. In cadaveric dissections the most common site is retrocaecal, but data from diagnostic laparoscopy indicate that the pelvic position is probably more common (Fig. 12.15). In children, there are abundant lymphoid follicles in the submucosa, but these atrophy with age.

Investigations

The various investigations used in patients with suspected appendicitis have already been discussed earlier in the chapter. However, the diagnosis of acute appendicitis is based on clinical assessment and there are no specific diagnostic tests. Ultrasonography in skilled hands might demonstrate a swollen non-compressible appendix, free fluid or even a mass in the right iliac fossa. If, after clinical assessment, the diagnosis remains in doubt, the clinician must proceed along one of two lines: either to carry out laparoscopy and undertake appendicectomy if indicated, or to institute a short policy of close and repeated observation with reassessment every hour. On occasions when there is diagnostic difficulty, and particularly in the elderly, abdominal CT can be helpful in making the diagnosis in addition to excluding other conditions (Fig. 12.16).

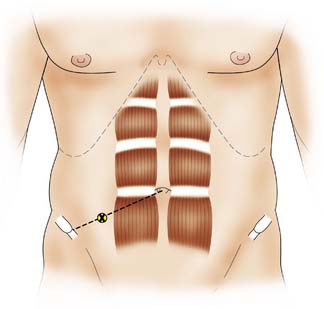

Management

The treatment of appendicitis is almost always surgical; increasingly, laparoscopic appendicectomy is being carried out, especially if a diagnostic laparoscopy has been performed first to establish the diagnosis (EBM 12.2). Although the laparoscopic approach is undoubtedly associated with less postoperative pain, most studies have so far failed to show significant advantages in shortening hospital stay or returning to normal activities. This is probably because of the underlying sepsis, which slows recovery. It is also possible to treat patients who do not have overt peritonitis non-operatively with antibiotics, and this is often done in areas of the world where ready access to surgery is impossible. In these conditions, there is a high incidence of recurrent problems and as such this practice is not favoured. If, by the time the patient presents, a mass can be felt, non-operative management with intravenous fluids and antibiotics is the treatment of choice, provided there are no signs of peritonitis (when an operation should be carried out). In these patients, an ultrasound scan should be arranged to look for an underlying abscess; if one is present, it should be drained either under radiological guidance or surgically.

Following successful non-operative treatment of an appendix mass, it used to be traditional practice to carry out an interval appendicectomy 3–6 months later. This prevents further attacks, and in the elderly makes sure that there is no underlying carcinoma of the caecum. However, several studies have now confirmed that after the successful non-operative treatment of either an appendix mass or an abscess, only a few patients develop recurrent problems, and most of them do so within the first few months. It is therefore reasonable not to carry out an interval appendicectomy unless the patient experiences further symptoms or complications (EBM 12.3). It is still important, especially in older patients, to exclude a carcinoma of the caecum by either double-contrast barium enema or colonoscopy. An interval appendicectomy should be undertaken if this course is not pursued.

Non-specific abdominal pain (NSAP)

Summary Box 12.2 Appendicitis

• Incidence has declined, but appendicitis is still the most common acute abdominal condition in childhood, adolescence and early adulthood

• The typical history of periumbilical colic (visceral midgut pain), followed within several hours by right iliac fossa pain (somatic pain from parietal peritonitis), is not always present

• Tenderness and muscle guarding in the right iliac fossa are the most reliable signs of acute appendicitis. Leucocytosis, high temperature and radiological signs are manifestations that may denote gangrene and perforation

• The diagnosis should be made and appendicectomy undertaken before gangrene and perforation supervene

• Gangrene and perforation are common and/or particularly dangerous in infants, during pregnancy and in the elderly.

if investigations such as laparoscopy are used to improve diagnostic accuracy. The major concern in reaching a diagnosis of NSAP is that a serious underlying condition has been missed. It has been reported that 10% of patients over 50 years of age who are discharged with NSAP from hospital after an acute admission with abdominal pain have an underlying malignancy, of which half are colonic. Another group of patients who tend to be diagnosed with NSAP are young females who may have a gynaecological condition, such as pelvic inflammatory disease or ovarian cyst pathology. With the more widespread use of laparoscopy in the investigation of patients with acute abdominal pain, the incidence of NSAP will continue to fall.

Gynaecological causes of the acute abdomen

Acute salpingitis

Summary Box 12.3 Gynaecological causes of pain and the acute abdomen

• Non-specific abdominal pain (i.e. pain for which no cause is defined) is particularly common in female adolescents and young women, and often mimics acute appendicitis. Laparoscopy may prove increasingly valuable when the diagnosis is in doubt and the need for surgery cannot be excluded

• Minor intraperitoneal bleeding at the time of rupture of the Graafian follicle may cause mid-cycle pain (Mittelschmerz) in the iliac fossa in young girls

• Rupture of an ectopic pregnancy causes intraperitoneal bleeding and more severe abdominal pain, with circulatory collapse. Signs of pregnancy are seldom present and pregnancy testing may be unhelpful. Elevation of the foot of the bed may produce shoulder-tip pain and underline the need for laparotomy

• Torsion of an ovarian cyst often causes cramping lower abdominal pain. Ovarian cysts can become very large and produce visible abdominal swellings which lie higher than might be expected. Some cysts prove to be malignant and care must be taken to avoid rupture at operation

• Acute salpingitis is often due to gonococcal infection and produces bilateral suprapubic pain which is often associated with urinary frequency, a tender cervix and vaginal discharge.