The acute abdomen and acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Basic principles of managing the acute abdomen

The first goal is to resuscitate the patient with intravenous fluids and give analgesia. The next is to make a broad diagnosis on the history, examination, laboratory tests and imaging (Box 19.1). All help decide if an operation is necessary, and its urgency, and clarify any non-surgical treatment, e.g. antibiotics for diverticulitis or conservative measures for acute pancreatitis. The differential diagnosis encompasses the likely pathophysiological phenomena responsible.

Disorders and diseases causing the acute abdomen

Pathophysiology of intestinal obstruction

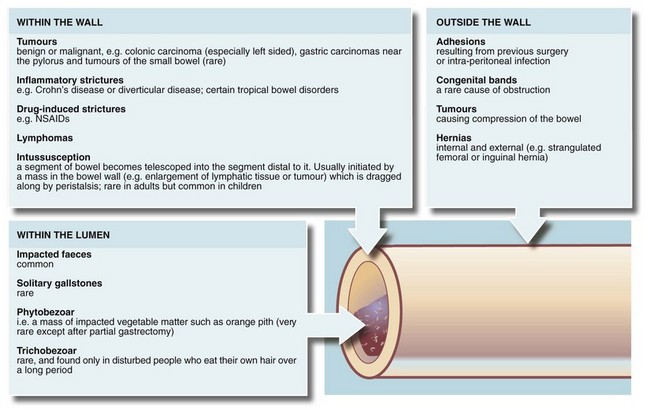

Any part of the gastrointestinal tract may become obstructed and present as an acute abdomen. Gastric outlet obstruction, however, presents differently and is described in Chapter 21. The causes of intestinal obstruction are many and varied, as outlined in Figure 19.1.

Symptoms of intestinal obstruction

Symptoms and physical signs are summarised in Box 19.2.

Vomiting: Bowel obstruction eventually leads to vomiting; the more proximal, the earlier it develops. Vomiting can occur even if nothing is taken by mouth because saliva and other GI secretions continue to be produced and enter the stomach. At least 10 litres of fluid are secreted into the GI tract each day. The nature of the vomitus gives clues about the level of obstruction. For example, vomiting of semi-digested food eaten a day or two earlier suggests gastric outlet obstruction. Copious vomiting of bile-stained fluid suggests upper small bowel obstruction. If the vomitus becomes thicker and foul-smelling (faeculent), more distal obstruction is likely and this change is often an indication for urgent operation. The term faeculent is a misnomer as the vomitus contains altered small bowel contents rather than faeces.

Pain: Fluid and swallowed air proximal to an obstruction plus continuing peristalsis cause pain. The general area of the pain gives clues to the embryological origin of the affected bowel: upper, middle or lower abdominal pain originates in foregut, midgut or hindgut respectively. In obstruction, pain is not usually the most prominent symptom. It is usually colicky, occurring in short-lived bouts as peristalsis attempts to overcome the obstruction. In small bowel, the peristaltic action often increases for 24–48 hours after the onset of obstruction and then fades.

Constipation: Absolute constipation, i.e. no faeces or flatus passed rectally, is pathognomonic of obstruction. The longer the duration, the more noteworthy it becomes in the diagnosis of obstruction.

Effects of the competence of the ileocaecal valve: Symptoms develop more gradually in large bowel obstruction because of the large capacity of colon and caecum and their absorptive capability. However, if the ileocaecal valve remains competent, no retrograde flow of accumulating bowel contents occurs and the thin-walled caecum progressively distends and eventually ruptures; operation is clearly more urgent in these cases. The ileocaecal valve becomes incompetent in about half the cases of large bowel obstruction. This allows the small bowel to distend, delaying the onset of obstructive symptoms and perhaps their acuteness.

Incomplete obstruction: If bowel is partially obstructed, clinical features are less distinct. Vomiting may be intermittent and the bowel habit erratic. Chronic incomplete obstruction leads to gradual hypertrophy of bowel wall muscle proximally and strong peristaltic activity causes bouts of colicky pain, often more severe than in complete obstruction. In thin patients, the pain is often accompanied by visible peristalsis, the hallmark of incomplete obstruction. The most common cause is a slowly progressively obstructing colonic cancer. Incomplete obstruction should not be called subacute obstruction as the term is misleading.

Physical signs of intestinal obstruction

General examination: Vomiting, diminished fluid intake and sequestration of fluid in the small bowel lead to dehydration. Gas-filled loops of bowel proximal to the obstruction produce abdominal distension; the more distal the obstruction, the greater the distension. Examination may also reveal signs of anaemia or lymphadenopathy attributable to the primary disorder.

Groin examination: It is essential that the groins are examined for hernias as the resultant bowel obstruction will not settle with conservative treatment. An obstructed femoral hernia is usually very small and rarely causes local symptoms or signs, even when strangulated. Hence it is easily missed if not specifically sought. Instead it produces the symptoms and signs of small bowel obstruction. This is an important clinical point—an obstruction due to an irreducible hernia will not settle with the usual conservative treatment.

Abdominal examination: On inspection, scars of previous operations provide a map of previous surgical disease, and raise the possibility of adhesive obstruction. On palpation, the most striking feature is the lack of abdominal tenderness except when strangulation has occurred. Obstruction with tenderness must be diagnosed as strangulation or perforation, necessitating urgent operation after fluid resuscitation. Note that a large obstructing abdominal mass may be palpable.

Radiological investigation of suspected bowel obstruction

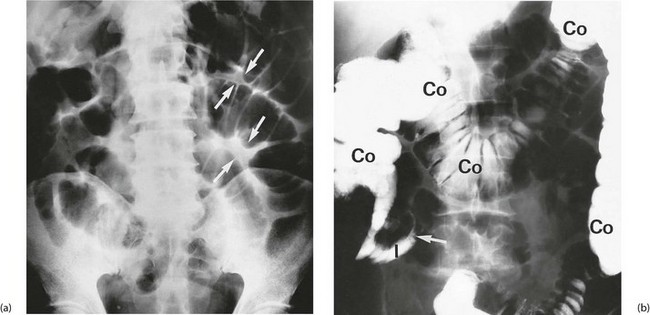

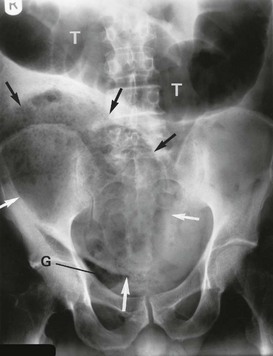

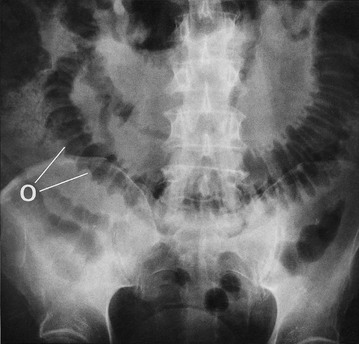

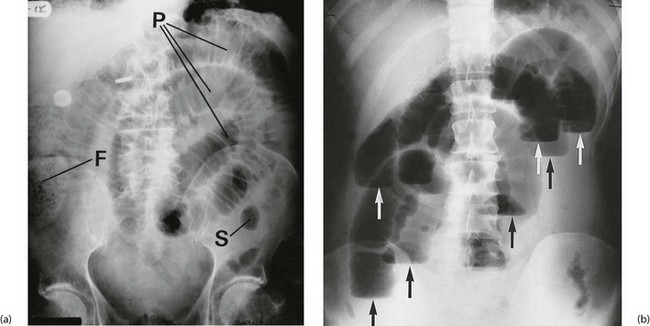

The most useful initial investigation is a plain supine abdominal X-ray (see Figs 19.2 to 19.4). The pattern and distribution of bowel gas often indicates the approximate site of obstruction. In small bowel obstruction, fluid levels may be visible on an erect or decubitus X-ray. Measuring the bowel diameter on X-ray gives the degree of distension. (See Box 19.1 for norms.)

Fig. 19.2 Radiological appearances of obstructed bowel

(a) Supine abdominal film in a man of 67 presenting with vomiting and abdominal distension. The film shows mid small bowel obstruction. Dilated small bowel fills the upper left quadrant and centre of the abdomen, and can be identified by the valvulae conniventes (plicae circulares P) which extend across the whole width of the lumen. The small bowel distal to the obstruction is collapsed and is not visible on this film. The large bowel is also collapsed, with faecal loading of the ascending colon (F) and only a small amount of gas in the sigmoid colon (S). Note also the metallic tip of the nasogastric (NG) tube and the incidental radiopaque gallstone.

(b) Erect film showing multiple loops of dilated small bowel and multiple fluid levels. The obstruction was caused by a small carcinoma of the medial wall of the caecum encroaching upon the ileal opening. Note: erect abdominal films are rarely taken nowadays

Principles of management of intestinal obstruction

• Resuscitation is an essential first step (see Ch. 4). Oral intake is discontinued and appropriate intravenous fluids given. After prolonged vomiting, patients may be seriously fluid and electrolyte depleted

• If the patient is vomiting and/or has marked small bowel dilatation, a nasogastric tube is passed and gastric contents aspirated. This controls nausea and vomiting, removes swallowed air and reduces gaseous distension. Most importantly, it minimises the risk of inhalation of gastric contents, particularly during induction of anaesthesia

• At least two-thirds of uncomplicated cases of obstruction are due to adhesions; these usually resolve with conservative measures employed for a maximum of 4 days

• Large bowel obstruction caused by faecal impaction can be relieved by enemas or manual removal of faeces

• Operation may be required to relieve the obstruction. Provided strangulation, obstructed hernia and caecal distension have been excluded, operation can safely be deferred for a day or two. This gives time for resuscitation and for any needed investigations. Nevertheless, few obstructions not beginning to settle within 48 hours resolve without intervention

• Bowel stenting—in some cases of left-sided colonic obstruction found to be due to cancer, the obstruction can be rapidly relieved with an endoscopically-placed expanding metal stent. Surgery can then be deferred until the patient’s condition has been optimised. If incurable metastatic disease has been identified, resectional surgery may be avoided altogether

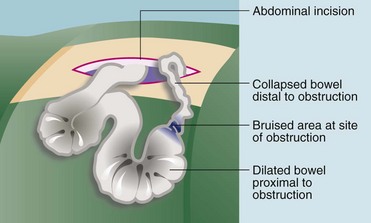

• At operation the cause of the obstruction is confirmed and dealt with appropriately (see Fig. 19.5)

Bowel strangulation

Symptoms and signs of bowel strangulation

Intra-abdominal strangulation causes the usual symptoms and signs of bowel obstruction (see Box 19.2) but accompanied by abdominal tenderness which should be an alerting signal. When compared with uncomplicated obstruction, strangulation patients are systemically more unwell, with a rising tachycardia and a leucocytosis.

Principles of management of suspected bowel strangulation

When strangulation is diagnosed or even suspected, operation must be performed urgently (after rapid fluid resuscitation) to try to prevent infarction and perforation (see Fig. 19.6). The patient is otherwise managed as for uncomplicated obstruction. Bowel strangulation is a clinical diagnosis best confirmed at laparotomy; there are no specific investigations to help.

Peritonitis

Pathophysiology and clinical features of peritonitis

On examination in generalised peritonitis, the abdomen is rigid and tender (but may not be evident in the very elderly or mentally obtunded) and bowel sounds are absent because of peristaltic paralysis. CT scans are often performed but rarely change management and may delay definitive treatment. The causes of peritonitis are summarised in Box 19.3.

Intra-abdominal abscess

Pathophysiology and clinical features of intra-abdominal abscess

Intra-abdominal abscesses tend to present with a worsening, continuous abdominal pain, diarrhoea or adynamic bowel disorder due to local bowel irritation and a swinging pyrexia. The last is an important sign of an abscess and there is usually marked leucocytosis. Patients are often relatively well, except with a postoperative abscess where a degree of systemic inflammatory response or multi-organ dysfunction is usual (see Ch. 3). There may be a palpable inflammatory mass, most commonly originating with acute appendicitis or acute diverticular disease. Rectal examination may reveal a hot, tender mass displacing the rectum backwards (a pelvic abscess)—a classic finding in the febrile post-appendicectomy patient. Patients usually complain of diarrhoea caused by inflammation near the rectum.

Ultrasound or CT of the abdomen and pelvis is most useful in demonstrating the site and size of an abscess, and drainage may be possible under imaging control (Fig. 19.7).

Perforation of an abdominal viscus

Pathophysiology and clinical features of perforation

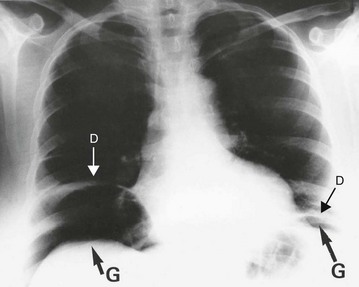

Perforation is essentially a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed by the presence of free gas in the peritoneal cavity on plain radiography (or CT scan). This is visible as a radiolucent line beneath the hemidiaphragms on an erect chest film (see Fig. 19.8) or a lateral decubitus abdominal film. Note that CT scanning is more sensitive than plain films for detecting small quantities of free gas. Free gas is rare in perforated appendicitis or perforated gall bladder. If imaging fails to support the clinical findings, action should be based on the clinical diagnosis.

Principles of management of perforation

Perforation is a surgical emergency. Most cases require urgent operation to repair the defect or resect the segment of diseased bowel. Duodenal ulcer perforations can be plugged with omentum at open surgery or laparoscopically. In large bowel perforations, a Hartmann’s procedure, which leaves a temporary colostomy (see Ch. 27), is frequently required because healing of an anastomosis may be impaired with gross peritoneal contamination, although there is a trend towards performing primary anastomosis even in these cases, together with a covering ileostomy. Very rarely, in perforation following colonoscopy, conservative management is appropriate if there are few clinical signs. This is because faecal contamination is minimal as the bowel is already clean. In the elderly or unfit, perforated duodenal ulcers may also be managed conservatively using restriction of oral fluids, nasogastric aspiration, acid suppression and antibiotics; however, the outcome is unpredictable and the approach should be reserved only for patients unsuitable for general anaesthesia or surgery.

Acute bowel ischaemia

Pathophysiology and clinical features of intestinal ischaemia

Acute occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) may lead to acute ischaemia of the primitive midgut-derived structures, i.e. jejunum, ileum and right colon (see Fig. 19.9). This causes massive infarction of the right side of the colon and most of the small bowel and later, fatal perforation. There are two types: embolism usually originates from left atrial thrombus in atrial fibrillation or from left ventricular wall thrombus after recent myocardial infarction; and thrombosis of the artery, usually a terminal event in gross low output cardiac failure or secondary to atherosclerotic stenosis. The vulnerability of the SMA territory is poorly understood, as is the sparing of the coeliac and inferior mesenteric territories, but it likely depends on the collateral blood supply.

Major gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Pathophysiology and clinical features

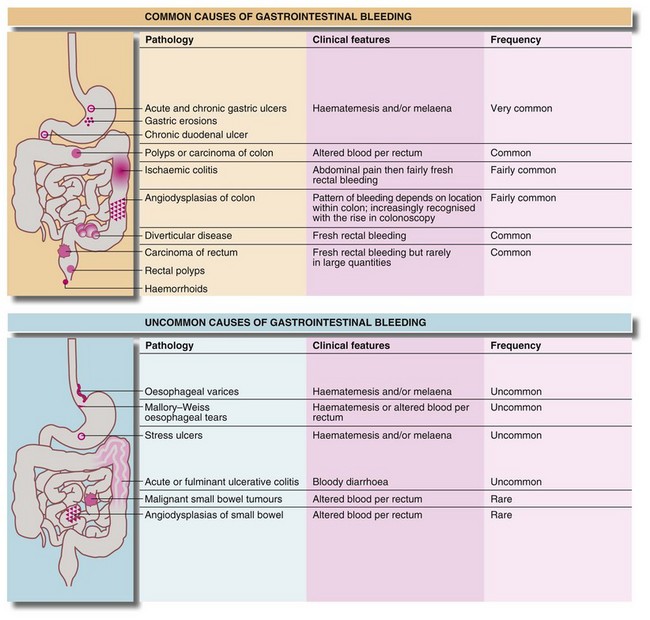

Blood loss beyond the duodenum is usually passed rectally. The extent to which it is altered by digestion and the degree of mixing with the stool are useful indicators of its level of origin and rate of bleeding. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is often manifest by melaena. This is the passage of loose, reddish-black, tarry stools with a characteristic foul smell. With upper gastrointestinal bleeding proximal to the duodeno-jejunal (DJ) flexure, haematemesis or melaena or both can occur. Haematemesis is more likely if the bleeding is rapid. The main causes of major gastrointestinal haemorrhage are summarised in Figure 19.10.

Management of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage

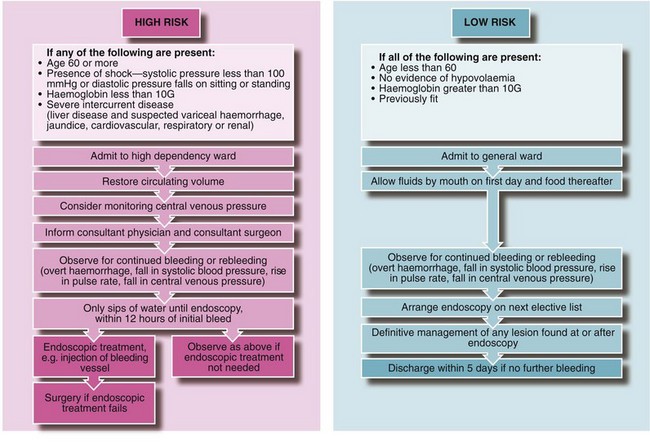

Initial management and resuscitation: Any patient with severe upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage is at risk of dying from hypovolaemic shock. This may occur with the initial event or as a result of rebleeding. High-risk patients (see Fig. 19.11) have about a 50% risk of rebleeding during a hospital stay; a combined medical/surgical management policy can reduce mortality for all cases of upper GI haemorrhage from 10% to about 2%. Hospitals should have clearly written and agreed protocols for this so patients do not slip through the net and perish by default (Fig. 19.11).

Clinical history, examination and investigation: In Western countries, more than two-thirds of patients with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage are over 60 and one-third of these have taken aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Alcohol consumption, previous peptic ulceration or gastric surgery, or a history of cirrhosis and variceal haemorrhage may also be important.

Estimating blood loss from the history is unreliable because a great deal of blood may remain in the bowel. It is essential to obtain good venous access early and then to perform a full blood count, urea and electrolytes and prothrombin ratio and liver function tests, to send blood for grouping and antibody screen (or cross-matching), and to order blood for transfusion in high-risk cases (see Fig. 19.11 and below). ECG and chest X-rays are useful in patients over 65 years or with cardiorespiratory disease. Note: the patient should be ready to go to the operating theatre at a moment’s notice if he or she suddenly deteriorates!

Stratification of risk: Patients with acute upper GI haemorrhage should be stratified clinically into either a low-risk group (non life-threatening) or a high-risk group (where continued bleeding or likely rebleeding is potentially life-threatening) (see Fig. 19.11 and next section).

Endoscopic management of acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: Patients clinically at high risk should be assessed early by a surgical team, even if admitted under the care of a gastroenterologist or (internal) physician. Ideally, the same surgical team should remain responsible for that patient until recovery so that a prompt decision to operate can be made if conservative management fails.

Patients with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage require endoscopy to determine the site and activity of bleeding, to diagnose oesophageal varices and to determine suitability for endoscopic treatment. Endoscopy also assists in locating the source if surgery becomes necessary. Urgent endoscopy, within 12 hours of the first bleed, should be performed in high-risk patients; all others should be endoscoped on the next available list. Even in the most acute upper GI haemorrhage, gastroscopy can usually be performed on the operating table before operation. Duodenal or gastric ulceration should be easily identifiable, but its real value is the ability to diagnose unusual sources of bleeding (e.g. Mallory–Weiss tear; see Ch. 22) and to avoid operating on unsuspected variceal haemorrhage. Even in patients with known varices, endoscopy is essential, as in 50% of cases, blood loss will be from a completely different lesion, e.g. peptic ulcer or gastric erosions.

• Active spurting from an artery in an ulcer bed. Endotherapy by gastroscopic injection of adrenaline (epinephrine) or an adrenaline/sclerosant mixture should be attempted; there is a 25–40% rebleed rate even in expert hands and the patient must be closely monitored as these often need surgery

• A visible elevated vessel or protruding adherent clot (Dieulafoy lesion). These lesions double the above risk of rebleeding to 50–80%. If the patient is hypotensive as a result of blood loss, the risk of rebleeding is 80%

• Bleeding gastro-oesophageal varices. Mortality is around 30%. Immediate treatment is required with endoluminal band ligation or injection sclerotherapy. Tamponade with special balloon catheters may also be necessary prior to endotherapy

High-risk patients should be commenced on a 72-hour intravenous infusion of high dose proton pump inhibitor. Low-risk patients usually stop bleeding with conservative management and are then unlikely to rebleed. They may be given sips of water, monitored for rebleeding, and endoscoped on the next available list.

Surgical management: A policy of early surgery for patients over 60 has been shown to reduce mortality. Urgent surgery is also required for patients defined clinically or endoscopically as at high risk, and who suffer one rebleed; or for any patient who suffers two rebleeds. Immediate surgery, including unguided laparotomy, is required for patients with exsanguinating haemorrhage or those unable to be stabilised during resuscitation.

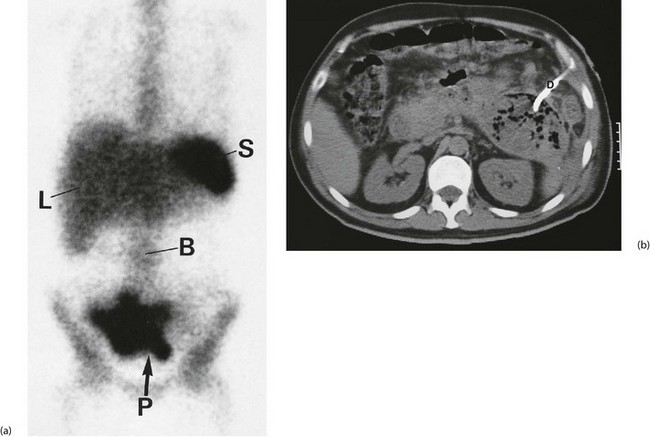

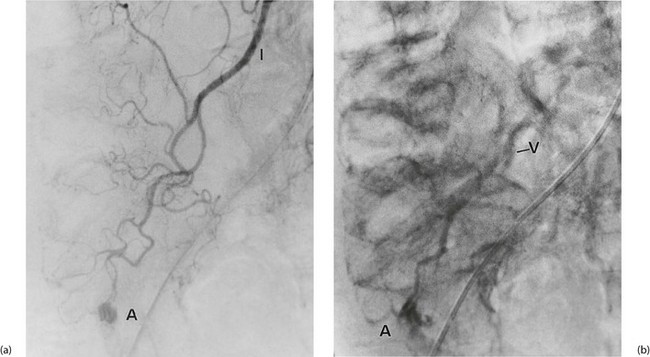

More distal gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Investigation involves colonoscopy, usually once the bleeding has stopped. Occasionally an unsuspected carcinoma or polyp is discovered. In ulcerative colitis, the diagnosis is evident from the other symptoms and signs, and management depends on the success of medical treatment (see Ch. 28). Persisting large bowel haemorrhage which is less rapid but recurrent is usually due to angiodysplasias (see Ch. 29). Colonoscopy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic for bleeding angiodysplasia. If colonoscopy is negative, impossible or unsatisfactory, radioisotope scanning using the patient’s own labelled red cells can be used; this has the advantage of identifying bleeding at rates as low as 0.05 ml/min. Highly selective arteriography is increasingly used in diagnosis of gastrointestinal haemorrhage but relies on much more rapid bleeding (greater than 0.5 ml/min) (see Fig. 19.12). At the time of arteriography, bleeding can be controlled with localised delivery of vasopressors or by coil embolisation.