Chapter 15 The Abdomen

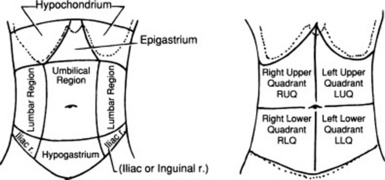

A. The Abdominal Wall

“Here too their sisters dwell.

And they are three, the Gorgons, winged,

With hair of snakes, hateful to mortals.

(1) Inspection

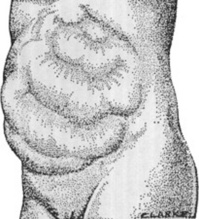

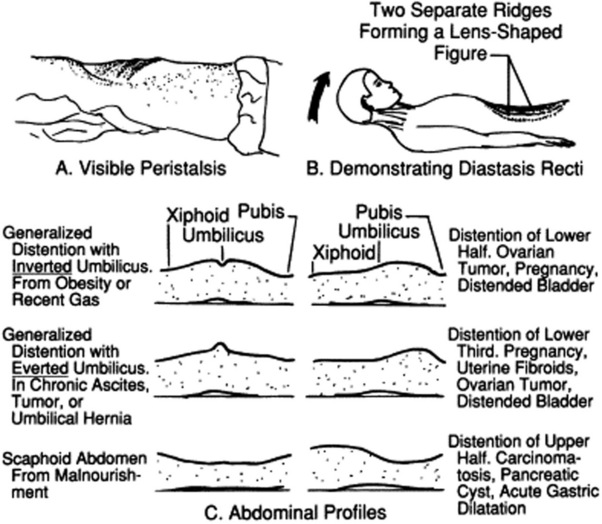

3 What are the most important contours on lateral inspection?

A Cupid’s bow profile is typical of acute pancreatitis, with the midpoint between the two bow branches coinciding with the umbilical retraction from localized peritonitis (Fig. 15-2).

A Cupid’s bow profile is typical of acute pancreatitis, with the midpoint between the two bow branches coinciding with the umbilical retraction from localized peritonitis (Fig. 15-2).

A discrete bulge in the epigastric area is seen in large pericardial effusions (Auenbrugger’s sign, from the name of the inventor of percussion). This lopsided protuberance should not be confused with a fat belly, which on lateral view appears instead as a convex arching of the abdominal contour, peaking at the umbilicus.

A discrete bulge in the epigastric area is seen in large pericardial effusions (Auenbrugger’s sign, from the name of the inventor of percussion). This lopsided protuberance should not be confused with a fat belly, which on lateral view appears instead as a convex arching of the abdominal contour, peaking at the umbilicus.

A localized bulge over the hypogastric area is typical of a distended urinary bladder (see Fig. 15-2).

A localized bulge over the hypogastric area is typical of a distended urinary bladder (see Fig. 15-2).

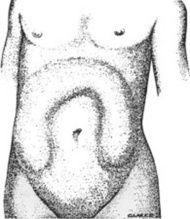

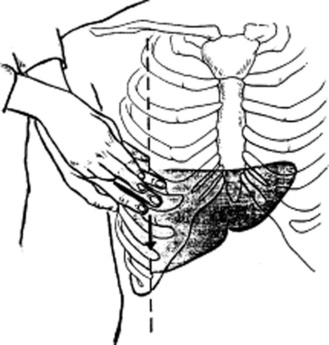

A bulge over the two upper quadrants is seen in hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 15-3).

A bulge over the two upper quadrants is seen in hepatosplenomegaly (Fig. 15-3).

A “ladder” pattern of abdominal distention is typical of small bowel obstruction (large bowel obstruction produces instead an inverted-U pattern) (see Fig. 15-4). Visible peristaltic waves also can occur in intestinal obstruction, and when associated with abdominal distention and hyperactive bowel sounds, they argue favorably for the presence of the condition. Unfortunately, visible peristalsis is only present in 6% of patients, and decreased or absent bowel sounds are present in one quarter of cases. In fact, more than one third of intestinal obstructions do not even have abdominal distention.

A “ladder” pattern of abdominal distention is typical of small bowel obstruction (large bowel obstruction produces instead an inverted-U pattern) (see Fig. 15-4). Visible peristaltic waves also can occur in intestinal obstruction, and when associated with abdominal distention and hyperactive bowel sounds, they argue favorably for the presence of the condition. Unfortunately, visible peristalsis is only present in 6% of patients, and decreased or absent bowel sounds are present in one quarter of cases. In fact, more than one third of intestinal obstructions do not even have abdominal distention.

Figure 15-2 Lateral abdominal contours. A, Cupid’s bow of pancreatitis. B, Fat. C, Bladder distention.

(Adapted from Sapira J: The Art and Science of Bedside Diagnosis. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1990.)

II Evaluation of the Umbilicus

4 What are the major abnormalities of the umbilicus?

Appearance of the umbilicus can provide valuable information (Fig. 15-5). There are three possible abnormalities: (1) protuberances, (2) purplish discolorations, and (3) a shift along the vertical line.

5 What are the most common protuberances?

Primarily two: (1) an eversion of the umbilical scar and (2) the Sister Mary Joseph nodule.

7 What is Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule?

It is the most ominous of all umbilical protuberances, since it represents a metastatic node by an intra-abdominal malignancy (see Chapter 18, questions 45 and 46). It presents as a nontender, irregular, and often exfoliative protuberance, either completely replacing the umbilicus or being palpable through it. It should not be confused with an omphalith, which is another umbilical nodule, but due instead to poor personal hygiene, resulting in collection of sebum and keratin.

8 What is the significance of a purplish discoloration of the umbilicus?

It is a sign of subcutaneous intraperitoneal bleed, usually from acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis. A periumbilical ecchymosis is commonly referred to as Cullen’s sign, and it is often encountered in association with Grey Turner’s, a bilateral reddish/purplish discoloration of the flanks. Both are poorly sensitive and poorly specific markers of hemorrhagic pancreatitis (see below, questions 13 and 116).

III Abdominal Respiratory Motion

11 How should the abdominal wall behave during normal respiration?

It should be synchronized with the chest wall, so that both expand in inspiration and contract in exhalation. In respiratory muscle weakness (and impending respiratory failure), the two become instead asynchronous, with respiratory alternans and abdominal paradox (see Chapter 13, questions 52–59).

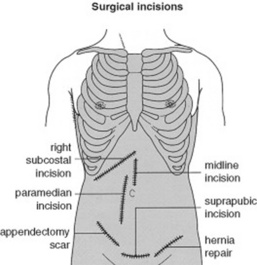

15 What about surgical scars?

Every surgical scar should be investigated and inquired about, since they can often be the telltale sign of old (and possibly current) pathology. Scars also should be reported in the patient’s record, by using a sketch to indicate their location in the four abdominal quadrants (Fig. 15-6).

V Abnormal Venous Patterns

17 How can you distinguish them?

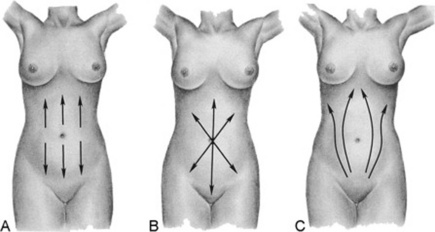

By identifying their location and direction of blood flow (Fig. 15-8):

A superior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the upper abdominal wall that has a downward flow.

A superior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the upper abdominal wall that has a downward flow.

An inferior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the lateral abdominal wall (flanks) that has an upward flow.

An inferior vena cava obstruction creates a venous engorgement of the lateral abdominal wall (flanks) that has an upward flow.

A portal system obstruction creates instead a periumbilical network of veins, with the most rostral draining upward and the most caudal draining downward.

A portal system obstruction creates instead a periumbilical network of veins, with the most rostral draining upward and the most caudal draining downward.

19 What is caput medusae?

It is the name given to the abnormal venous networks of portal hypertension. It is most commonly seen in cirrhotics whose umbilical vein has reopened (see Cruveilhier-Baumgarten murmur, disease, and syndrome, discussed in question 34). This presents with a tuft of veins radiating from the umbilicus as spikes of a wheel or a nest of snakes; hence, the name. Some of these engorged veins drain rostrally into the internal mammary, whereas others drain caudally into the inferior mammary.

29 What is the significance of an abdominal murmur/bruit?

It depends on its location. This may be either epigastric or right/left upper quadrant.

30 What is the significance of an epigastric murmur?

A systolic, medium- to low-pitched murmur over the epigastrium is not uncommon in healthy individuals. It occurs especially often in pregnancy, and, in fact, as many as one fifth of normal and thin women may have it, too (this frequency is a little lower in men). In contrast to a pathologic finding (like the murmur of renal artery stenosis, which tends to be louder outside the epigastrium [see below, questions 122 and 123]), a benign murmur is characteristically limited to the area between the xiphoid process and umbilicus. It usually originates from a normal celiac tripod.

31 What is the significance of a right or left upper quadrant murmur/bruit?

When over the right upper quadrant, it often indicates a hepatic tumor, typically a hepatoma but also a metastasis. It is due to tumoral neovascularization or extrinsic vascular compression by the cancer, but also can reflect hepatitis, cirrhosis, an arteriovenous malformation, or, occasionally, simple tricuspid regurgitation.

When over the right upper quadrant, it often indicates a hepatic tumor, typically a hepatoma but also a metastasis. It is due to tumoral neovascularization or extrinsic vascular compression by the cancer, but also can reflect hepatitis, cirrhosis, an arteriovenous malformation, or, occasionally, simple tricuspid regurgitation.

When over the left upper quadrant, it indicates instead cancer of the pancreas or a vascular anomaly of the spleen. Less frequent causes of a left (or right) upper quadrant murmur/bruit are aneurysmatic lesions of the abdominal aorta or of renal, celiac, and mesenteric vessels.

When over the left upper quadrant, it indicates instead cancer of the pancreas or a vascular anomaly of the spleen. Less frequent causes of a left (or right) upper quadrant murmur/bruit are aneurysmatic lesions of the abdominal aorta or of renal, celiac, and mesenteric vessels.

Finally, renal vascular disease of the right (or left) kidney also may produce a systolic murmur in the upper quadrants. Yet, these lesions are more commonly associated with a continuous murmur (i.e., a bruit). This can be heard, albeit less strongly, over the epigastrium, too.

Finally, renal vascular disease of the right (or left) kidney also may produce a systolic murmur in the upper quadrants. Yet, these lesions are more commonly associated with a continuous murmur (i.e., a bruit). This can be heard, albeit less strongly, over the epigastrium, too.

34 What are Cruveilhier-Baumgarten disease and Cruveilhier-Baumgarten syndrome?

The disease is a congenital patency of the umbilical vein, even though portal hypertension may be absent. Patients with this condition do not have ascites, but may have a small and atrophic liver—like the first patient described by Cruveilhier (see below, question 35).

The disease is a congenital patency of the umbilical vein, even though portal hypertension may be absent. Patients with this condition do not have ascites, but may have a small and atrophic liver—like the first patient described by Cruveilhier (see below, question 35).

The syndrome is instead typical of portal hypertension from cirrhosis and consists of either an acquired reopening of the umbilical vein or high flow in paraumbilical/anastomotic veins.

The syndrome is instead typical of portal hypertension from cirrhosis and consists of either an acquired reopening of the umbilical vein or high flow in paraumbilical/anastomotic veins.

IV Succussion Splash

37 What is a succussion splash?

It is the noise of shaking a body cavity with a large amount of air and water. Hippocrates was the first to describe it, probably in reference to a hydropneumothorax. Stressing its diagnostic value, he wrote: “You shall know that the chest contains water but not pus, if in applying the ear during a certain time on the side, you perceive a noise like that of boiling vinegar.” If elicited in the abdomen, it reflects instead an intestinal obstruction or a gastric dilation (see below, question 114). Although often detected by the unaided ear, it usually requires a stethoscope.

41 What is the difference between a light and a deep palpation?

In light palpation, the palm of the hand rests gently on the wall, while the fingers are pressed into the abdomen at a depth of 1 cm.

In light palpation, the palm of the hand rests gently on the wall, while the fingers are pressed into the abdomen at a depth of 1 cm.

Deep palpation is the same as light palpation, except that the examiner presses his or her fingers more deeply than 1 cm. This technique is usually carried out by reinforced palpation (i.e., by pushing on the fingers of the palpating hand with the fingers of the other hand [bimanual palpation]; Fig. 15-9).

Deep palpation is the same as light palpation, except that the examiner presses his or her fingers more deeply than 1 cm. This technique is usually carried out by reinforced palpation (i.e., by pushing on the fingers of the palpating hand with the fingers of the other hand [bimanual palpation]; Fig. 15-9).

42 How can one distinguish between an intra-abdominal and an intramural mass?

By palpating the mass while the patient is raising the head from the pillow. This tenses the abdominal wall muscles, thus pushing away an intra-abdominal mass but not an intra-mural mass (i.e., one localized in the abdominal wall). This technique also can be used to separate the abdominal wall from peritoneal tenderness (see below, questions 153–160).

Examples of Abnormalities Detectable On Palpation

B. Liver

“Zeus’ winged hound, an eagle red with blood,

Shall come a guest unbidden to your banquet.

All day long he will tear to rags your body,

feasting in a fury on the blackened liver.

Look for no end to this agony,

Until a God will freely suffer for you,

will take on Him your pain, and in your stead

(1) Palpation of the Liver

46 Which edge can be palpated? How?

Only the lower edge is accessible, since the upper border is tucked deep into the rib cage and thus beyond the reach of the examiner’s fingers. To access the lower margin, ask the patient to lie supine, ideally with flexed hips and knees to better relax the abdominal wall (Fig. 15-10). To feel the edge, you can use one of three strategies, differing more in personal preference than value:

Cephalad approach: Place one hand on the patient’s abdomen, keeping the edge parallel to the rectus muscle and the fingers pointing toward the head. Place the other hand behind the patient’s back, to help support it. Then, while the patient is taking a deep breath, press the anterior hand downward and cephalad, so that the respiratory excursion of the diaphragm displaces the liver edge downward, bringing it into contact with the fingertips.

Cephalad approach: Place one hand on the patient’s abdomen, keeping the edge parallel to the rectus muscle and the fingers pointing toward the head. Place the other hand behind the patient’s back, to help support it. Then, while the patient is taking a deep breath, press the anterior hand downward and cephalad, so that the respiratory excursion of the diaphragm displaces the liver edge downward, bringing it into contact with the fingertips.

Transverse approach: Place your hand parallel to the costal margin (with fingers pointing toward the patient’s flank). This is probably not as good a maneuver as the other two, since it relies primarily on the hand’s margin, which is not as sensitive as the fingertips.

Transverse approach: Place your hand parallel to the costal margin (with fingers pointing toward the patient’s flank). This is probably not as good a maneuver as the other two, since it relies primarily on the hand’s margin, which is not as sensitive as the fingertips.

Hook technique: Point your fingers toward the patient’s feet, while trying to gently hook the liver with both hands.

Hook technique: Point your fingers toward the patient’s feet, while trying to gently hook the liver with both hands.

53 What is the hepatojugular reflux?

More of a cardiac than an abdominal maneuver. In fact, it is commonly used to unmask subclinical congestive heart failure (for its description and clinical significance, see Chapter 10, questions 106–114).

58 How can one best determine hepatic size by percussion?

Through direct or indirect percussion (Fig. 15-11). Both are carried out during quiet respiration. The direct technique consists of a light abdominal percussion by the index finger alone. Indirect percussion is instead the more traditional combination of plexor and pleximeter, as, respectively, the striking and stricken finger. The pleximeter (usually the middle finger of one hand) is applied to the abdominal wall only by its distal interphalangeal joint (to avoid dampening of vibrations); the middle finger of the other hand is then used as a plexor against the pleximeter, usually tapping along the right MCL. Even when performing indirect percussion, it is important that you tap lightly, making the note barely audible to only yourself. By doing so, you can more easily identify the hepatic area as a change in percussion note, from resonant (pulmonary parenchyma), to dull (liver), and to resonant again (air-filled bowel loops). Yet, even this may lead to inaccuracies. Vertical liver span is the distance between two resonant points along the MCL, detected during either quiet breathing, or at the same phase of respiration. Direct percussion performed by gastroenterologists has been found to be more accurate than indirect percussion, yet a normal range of liver span for this technique has not been determined. Thus, indirect percussion should still be the maneuver of choice.

60 What is the scratch test?

It is a combined auscultatory/percussive maneuver aimed at localizing the inferior hepatic border (Fig. 15-12). Place the stethoscope either beneath the xiphoid or over the liver, just above the costal margin of the MCL. Then administer “scratches” in a cephalad fashion, by moving the finger along the MCL—from the right lower quadrant toward the costal margin. The point at which the scratching sound intensifies indicates a change in underlying tissue, and thus the presence of the lower liver edge. A variation of the test is auscultatory percussion, in which the examining finger does not scratch the abdominal wall but gently percusses it (or flickers it).

63 In summary, what are the pros and cons of bedside assessment of liver size?

When compared with firm percussion, light percussion underestimates liver size, yet it is still closer to ultrasonic evaluation.

When compared with firm percussion, light percussion underestimates liver size, yet it is still closer to ultrasonic evaluation.

Measurements by direct and indirect percussion vary significantly.

Measurements by direct and indirect percussion vary significantly.

Palpability of the lower liver edge is a totally inaccurate marker of hepatomegaly.

Palpability of the lower liver edge is a totally inaccurate marker of hepatomegaly.

The scratch test needs further validation.

The scratch test needs further validation.

Liver span measured by physical exam does not correlate with the actual size of the liver.

Liver span measured by physical exam does not correlate with the actual size of the liver.

71 Is there any diagnostic difference in the hue of pigmentation?

Subconjunctival fat: This can be yellowish and often misinterpreted as jaundice, except that the yellow of fat is confined to the conjunctival folds and never to the pericorneal region.

Subconjunctival fat: This can be yellowish and often misinterpreted as jaundice, except that the yellow of fat is confined to the conjunctival folds and never to the pericorneal region.

Hypercarotenemia: This may result from excessive ingestion of carrots or pigmented fruits and vegetables (oranges and tomatoes). In this case, the yellowish discoloration spares the conjunctiva while affecting predominantly the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.

Hypercarotenemia: This may result from excessive ingestion of carrots or pigmented fruits and vegetables (oranges and tomatoes). In this case, the yellowish discoloration spares the conjunctiva while affecting predominantly the palms, soles, and nasolabial folds.

74 Can spider nevi occur in normal individuals?

Liver disease, especially alcoholic: Alcohol plays an important role, since lesions are indeed more frequent in alcoholic cirrhosis (and cirrhosis due to hepatitis C and alcohol) than in cirrhosis due solely to hepatitis C. In male cirrhotics, the angiomas tend to correlate with an abnormally increased serum ratio of estradiol to free testosterone. They also correlate with higher levels of substance P, which may play a vasodilator role through its release of nitric oxide. They typically wax and wane according to disease severity, and can predict both the stage of hepatitis C and the presence of hepatopulmonary syndrome.

Liver disease, especially alcoholic: Alcohol plays an important role, since lesions are indeed more frequent in alcoholic cirrhosis (and cirrhosis due to hepatitis C and alcohol) than in cirrhosis due solely to hepatitis C. In male cirrhotics, the angiomas tend to correlate with an abnormally increased serum ratio of estradiol to free testosterone. They also correlate with higher levels of substance P, which may play a vasodilator role through its release of nitric oxide. They typically wax and wane according to disease severity, and can predict both the stage of hepatitis C and the presence of hepatopulmonary syndrome.

Pregnancy: Spiders appear during the second to fifth months of gestation and quickly disappear after delivery. Same with oral contraceptives.

Pregnancy: Spiders appear during the second to fifth months of gestation and quickly disappear after delivery. Same with oral contraceptives.

75 What is the hepatopulmary syndrome (HPS)?

A condition seen in 8% of cirrhotics and characterized by hypoxemia and spider nevi. The mechanism is bibasilar intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunt, due to multiple “spider angiomata.” These, in turn, cause clubbing, orthodeoxia, and platypnea (see Chapter 13, questions 46 and 47). Diagnosis is confirmed by a positive bubble echocardiogram, and liver transplant is often curative. HPS should not be confused with portopulmonary hypertension (PHTN), which is instead a condition of cirrhotics with portal and pulmonary hypertension (the latter being akin to primary pulmonary hypertension). Oxygenation is normal at rest, but not on exercise; there is orthopnea (but not platypnea), plus right-sided failure. Pulmonary hypertension does not respond to transplant.

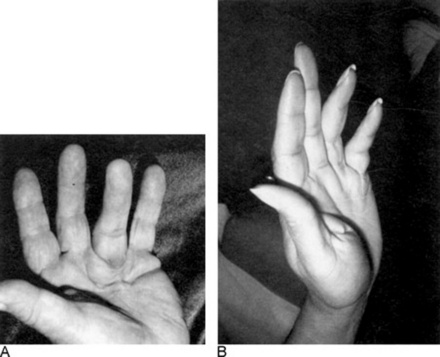

77 What is Dupuytren’s contracture?

It is a benign and slowly progressive fibroproliferative disease, characterized by thickening of the palmar fascia on the ulnar side, eventually leading to flexural contraction of the digits, especially the fourth and fifth (the index finger and thumb are instead typically spared) (Fig. 15-13). In addition to the flexion deformity of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there also may be firm palmar nodules (possibly tender to palpation) and palpable “cords” (proximal to the nodules and usually painless). Most patients are bilaterally affected (65%), whereas unilateral cases tend to be mostly right sided. The hand of Dupuytren is so typical to have been dubbed “the hand of Papal benediction” (which is different from the “obstetrician’s hand” of Trousseau’s sign—see Chapter 2, questions 104–107). Dupuytren’s also is familial (27–68% of cases), with males more frequently and more severely affected. It is very common in northern Europe and the United Kingdom, and especially in countries with large immigration from these areas. In Scotland, for example, it affects 39% of males and 21% of females older than 60. In the United States, it affects instead 5–15% of males older than 50. The basic pathophysiology is uncontrolled fibroblast proliferation of the palmar fascia. Etiology is unknown, but several associations are known: (1) 18–66% of patients with alcoholic liver disease (either cirrhotic or noncirrhotic); (2) 13–42% of patients with chronic pulmonary tuberculosis; (3) 8–56% of epileptics on treatment; (4) 35% of smoker males older than 60, usually. In some studies, manual laborers (and brewery workers) have a slightly higher predominance, but this is still controversial. Prior hand trauma is, however, a risk factor, present in 13% of cases. In addition, 31–48% of Dupuytren patients are just alcoholics (with or without liver disease); 10–35% have either peptic ulcer disease or cholecystitis; 6–25% have diabetes mellitus (strongly correlated with retinopathy); 93% have glucose intolerance; and 2.5% have Peyronie’s disease. Famous sufferers have included former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the late U.S. President Ronald Reagan, suggesting that conservative views might represent an additional risk factor.

79 What is asterixis?

A common (and early) finding of hepatic encephalopathy and a classic sign of hepatocellular disease. Since it requires some degree of voluntary muscular contraction, it disappears in comatose patients. It is demonstrated by asking patients to stretch the arms while at the same time holding their fingers spread apart, as if they were “stopping traffic.” In the case of asterixis, the fingers and hands will start “flapping” in a myoclonic fashion, with brisk movements occurring at intervals of less than 1 second to more than 1 second (see Chapter 20, questions 50–52).

C. Gallbladder

83 What are Murphy’s signs?

Additional maneuvers that, in addition to “the” original sign, also carry Dr. Murphy’s name. In fact, he humbly considered these techniques “the most valuable contributions I have made to medicine and surgery in the way of aids to diagnosis.” One of them (percussion of the costovertebral angle for presence of kidney pathology, especially a perinephric abscess) has long lost its linkage with Murphy’s name, even though it is still routinely used (see below, questions 118–120). The other ones are:

90 Why should the gallbladder of patients with cholelithiasis remain small?

Two possibilities, the first proposed by Courvoisier himself and probably not as accurate:

Recurrent biliary colic caused by stone migration tends to lead to chronic cholecystitis and thus to a stiffening of the gallbladder wall. This, in turn, prevents the gallbladder from enlarging whenever the passing of new stones causes additional obstruction. Conversely, the slow growth of a biliary duct cancer (or of a cancer of the head of the pancreas), coupled with the pliability of the gallbladder, leads to painless jaundice and a palpable, enlarged gallbladder. This hypothesis, however, conflicts with experimental data indicating a similar stiffness in gallbladders that are either dilated or nondilated.

Recurrent biliary colic caused by stone migration tends to lead to chronic cholecystitis and thus to a stiffening of the gallbladder wall. This, in turn, prevents the gallbladder from enlarging whenever the passing of new stones causes additional obstruction. Conversely, the slow growth of a biliary duct cancer (or of a cancer of the head of the pancreas), coupled with the pliability of the gallbladder, leads to painless jaundice and a palpable, enlarged gallbladder. This hypothesis, however, conflicts with experimental data indicating a similar stiffness in gallbladders that are either dilated or nondilated.

Biliary colic from stones is less likely to produce a complete ductal obstruction. It also is more likely to be symptomatic and thus acted upon quickly, whereas malignant obstructions tend to be more severe, cause higher intraductal pressures, and last longer.

Biliary colic from stones is less likely to produce a complete ductal obstruction. It also is more likely to be symptomatic and thus acted upon quickly, whereas malignant obstructions tend to be more severe, cause higher intraductal pressures, and last longer.

D. The Spleen

98 What is the best way to palpate the spleen?

It varies, depending on the examiner. As for the patient’s position, some physicians prefer the supine approach (from either the right or the left side), whereas others have the patient in right lateral decubitus position. These have all been compared and found to be equivalent; hence, personal preference remains the major factor (Fig. 15-14). Overall, there are as many as four techniques: (1) bimanual, (2) ballottement, (3) palpation from above, and (4) one-hand hook technique. As in the case of the liver exam, any of these would benefit from having the patient flex the knees and hips.

Bimanual palpation: Stand at the right side of the supine patient, and apply gentle pressure with your right hand to the left upper abdominal quadrant, keeping the fingers parallel to the rectus muscle and pointing toward the patient’s head. Place your left hand on the lower left rib cage. Then instruct the patient to breathe in slowly, so that at peak inspiration the splenic edge will touch your fingers. If you cannot feel the edge, end the examination there. If you do feel it, determine its consistency and contour, and then listen for rubs and bruits.

Bimanual palpation: Stand at the right side of the supine patient, and apply gentle pressure with your right hand to the left upper abdominal quadrant, keeping the fingers parallel to the rectus muscle and pointing toward the patient’s head. Place your left hand on the lower left rib cage. Then instruct the patient to breathe in slowly, so that at peak inspiration the splenic edge will touch your fingers. If you cannot feel the edge, end the examination there. If you do feel it, determine its consistency and contour, and then listen for rubs and bruits.

Ballottement: Use your left hand to reach over and around the supine patient’s left hemithorax, lifting it up. Use your right hand to feel for transmission of impulses by a large spleen.

Ballottement: Use your left hand to reach over and around the supine patient’s left hemithorax, lifting it up. Use your right hand to feel for transmission of impulses by a large spleen.

Palpation from above: The patient lies either supine or in the right lateral decubitus position, while you stand on the left side of the bed, pointing all fingers toward the patient’s feet, trying to hook the spleen gently with both hands while asking the patient to take a deep breath.

Palpation from above: The patient lies either supine or in the right lateral decubitus position, while you stand on the left side of the bed, pointing all fingers toward the patient’s feet, trying to hook the spleen gently with both hands while asking the patient to take a deep breath.

One-hand hook technique: Although not validated, this method should detect an enlarged spleen weeks before it becomes palpable by more conventional maneuvers. In the words of Dr. Hedge, who first described it:

One-hand hook technique: Although not validated, this method should detect an enlarged spleen weeks before it becomes palpable by more conventional maneuvers. In the words of Dr. Hedge, who first described it:

102 Which other findings may help identifying the cause of splenomegaly?

Concomitant hepatomegaly suggests primary liver disease (causing splenomegaly through portal hypertension).

Concomitant hepatomegaly suggests primary liver disease (causing splenomegaly through portal hypertension).

Lymphadenopathy excludes primary liver disease and makes hematologic or lymphoproliferative disorders more likely.

Lymphadenopathy excludes primary liver disease and makes hematologic or lymphoproliferative disorders more likely.

Massive splenomegaly (or left upper quadrant tenderness) also argues in favor of a myeloproliferative etiology.

Massive splenomegaly (or left upper quadrant tenderness) also argues in favor of a myeloproliferative etiology.

(2) Percussion of the Spleen

104 How do you percuss the spleen?

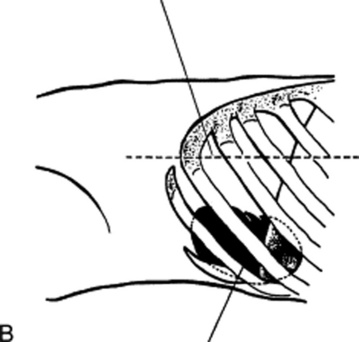

Nixon’s technique (Fig. 15-15A) percusses the entire spleen outline while the patient is in the right lateral decubitus position. This allows the spleen to lie above the stomach and colon, thus permitting determination of both upper and lower margins. Nixon described it in 1954 as follows:

Nixon’s technique (Fig. 15-15A) percusses the entire spleen outline while the patient is in the right lateral decubitus position. This allows the spleen to lie above the stomach and colon, thus permitting determination of both upper and lower margins. Nixon described it in 1954 as follows:

Castell’s technique (Fig. 15-15B) percusses the lowest left intercostal space (eighth or ninth) along the anterior axillary line. The patient is instructed to breathe in deeply and then exhale, while percussion is carried out during both inspiration and exhalation. This should normally yield a resonant note, even on deep inspiration. However, enlarged spleens (even those missed on palpation, or just barely palpable) would yield a dull percussion note at peak inspiration. Castell described this technique in 1967 as follows:

Castell’s technique (Fig. 15-15B) percusses the lowest left intercostal space (eighth or ninth) along the anterior axillary line. The patient is instructed to breathe in deeply and then exhale, while percussion is carried out during both inspiration and exhalation. This should normally yield a resonant note, even on deep inspiration. However, enlarged spleens (even those missed on palpation, or just barely palpable) would yield a dull percussion note at peak inspiration. Castell described this technique in 1967 as follows:

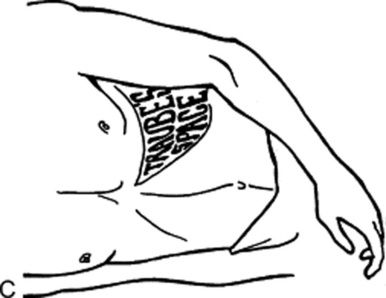

Percussion of Traube’s semilunar space (Fig. 15-15C): Described by Barkun et al. in 1989, Traube’s space is a triangular area bordered by the left sixth rib superiorly, the left midaxillary line laterally, and the left costal margin inferiorly. In the original description, dullness in this area suggested a pleural effusion. More recently, it has been thought to indicate splenomegaly.

Percussion of Traube’s semilunar space (Fig. 15-15C): Described by Barkun et al. in 1989, Traube’s space is a triangular area bordered by the left sixth rib superiorly, the left midaxillary line laterally, and the left costal margin inferiorly. In the original description, dullness in this area suggested a pleural effusion. More recently, it has been thought to indicate splenomegaly.

E. The Stomach

“The stomach is what distinguishes animals from vegetables;

for we do not know any vegetable that has a stomach, nor any animal without one.”

F. The Pancreas

116 What is the role of physical diagnosis in assessing the pancreas?

Arching of the abdominal wall, or Cupid’s bow profile (see also question 3 and Fig. 15-2)

Arching of the abdominal wall, or Cupid’s bow profile (see also question 3 and Fig. 15-2)

Tenderness to percussion of the thoracolumbar spine (or to palpation of the left upper quadrant). The latter is seen in patients lying in the right lateral decubitus position and with knees flexed to the chest (Mallet-Guy’s sign, from the French surgeon who first described it).

Tenderness to percussion of the thoracolumbar spine (or to palpation of the left upper quadrant). The latter is seen in patients lying in the right lateral decubitus position and with knees flexed to the chest (Mallet-Guy’s sign, from the French surgeon who first described it).

Sequelae of pancreatitis. The most common is a pseudocyst, which may manifest as a visible deformation of the abdominal wall—palpable in 50% of the patients.

Sequelae of pancreatitis. The most common is a pseudocyst, which may manifest as a visible deformation of the abdominal wall—palpable in 50% of the patients.

G. The Kidneys

(1) Auscultation of the Kidneys

122 What is the role of renal auscultation?

Anterior systolic murmurs are heard along an anterior horizontal band that crosses the umbilicus. Although quite sensitive, these have disappointing specificity for renovascular disease, with false positive rates as high as 30%—especially in hypertensive patients.

Anterior systolic murmurs are heard along an anterior horizontal band that crosses the umbilicus. Although quite sensitive, these have disappointing specificity for renovascular disease, with false positive rates as high as 30%—especially in hypertensive patients.

Posterior systolic murmurs are instead localized to the area between the lumbar column and the costal margins. They are valuable only if present, since they have high specificity for renovascular disease (close to 100%), but very low sensitivity (10%).

Posterior systolic murmurs are instead localized to the area between the lumbar column and the costal margins. They are valuable only if present, since they have high specificity for renovascular disease (close to 100%), but very low sensitivity (10%).

H. The Urinary Bladder

125 Is the urinary bladder palpable?

Only when distended—and only in thin patients or bladders fibrotic from radiation therapy.

128 What is the physical diagnosis gold standard for detecting a full bladder?

It remains percussion—either alone or coupled with auscultation:

Plain percussion: To carry this out, percuss rostrocaudally along the midline, from the umbilicus to the symphysis, until you reach a level of suprapubic dullness (corresponding to the fundus of the bladder). This is neither sensitive (it requires 400–600 mL of urine) nor specific (many patients with suprapubic dullness do not have an enlarged bladder). And yet, in cases of sizable distention, the extent of suprapubic dullness does indeed correlate with bladder volume.

Auscultatory percussion: This is a combined percussive and auscultatory maneuver that can be used to localize the upper border of the bladder. To carry it out:

Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope along the midline, just above the symphysis pubis.

Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope along the midline, just above the symphysis pubis.

Administer “scratches” in a rostrocaudal fashion, by moving your finger along the vertical midline—from the umbilicus downward, 1 cm at a time.

Administer “scratches” in a rostrocaudal fashion, by moving your finger along the vertical midline—from the umbilicus downward, 1 cm at a time.

The point at which the scratching sound intensifies indicates a change in underlying tissue and thus locates the upper edge of the bladder.

The point at which the scratching sound intensifies indicates a change in underlying tissue and thus locates the upper edge of the bladder.

I. Ascites (Dropsy)

“I walk as I were girdled with my spleen

And look as if my belly carried twins

139 How is the shifting-dullness maneuver performed?

Ask the patient to lie supine. Then percuss the abdomen along one flank—from the umbilicus downward. Mark the level at which the percussion note turns from resonant to dull, and then ask the patient to roll over on the right side. Once the patient is in the right lateral decubitus position (and supported by a 45-degree–angle pillow), restart the percussion sequence. A gravity-dependent shift in dullness of at least 1 cm (with the shifting border still remaining horizontal) indicates that the dullness is due to fluid, whereas absence of a shift indicates that the dullness is due to a solid organ. Once again, tympany and dullness remain separated by a horizontal border (Fig. 15-16).

141 How is the fluid-wave maneuver performed?

It requires two examiners, or one examiner assisted by the patient. With the patient supine, place one hand on one flank and tap gently on the opposite flank. In the meantime, ask the other examiner (if available) to place the ulnar surface of both hands over the patient’s umbilicus and along the abdominal vertical midline (from the xiphoid process to the symphysis pubis). This is done to prevent a false positive fluid wave, which may occur whenever flickering of the abdominal wall creates ripples of mesenteric fat (not of ascites) toward the contralateral side. If an assistant is unavailable, ask the patient to place the ulnar surface of one hand vertically over the umbilicus. The test is positive when you feel a fluid wave emanating into the contralateral side. This has to be of moderate to strong intensity. Slight fluid waves have high interobserver variability and should not be relied on for diagnosing ascites (see Fig. 15-17).

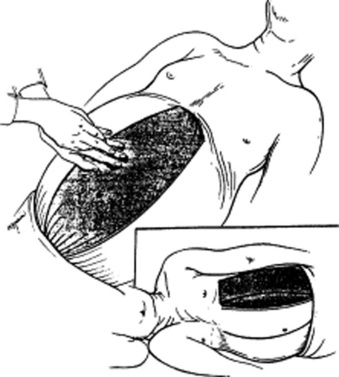

144 What is the puddle sign? How is it elicited?

It is a sign of auscultatory percussion, performed by asking patients first to lie on their belly for 5 minutes and then eventually to raise themselves by supporting their body weight on the knees and stretched forearms (Fig. 15-18). As a result, the middle portion of the abdomen becomes pendulous and dependent. At this point, you should place the diaphragm of your stethoscope over the lowest abdominal area, while at the same time flicking a finger over a localized flank area. Then gradually move your stethoscope over the opposite flank. The test is positive when there is a sudden increase in intensity and clarity of the sound, signaling that the stethoscope has passed the edge of the peritoneal fluid.

Figure 15-18 Patient positioning for eliciting the puddle sign.

(From Dioguardi N, Sanna GP: Moderni Aspetti di Semeiotica Medica. Milan, Societa Editrice Universo, 1975.)

148 What is the role of the Bayes’ theorem in diagnosing ascites at the bedside?

A very important one, since interpreting each maneuver in light of the pretest probability of disease is the best way to improve accuracy. Because the predictive value of any test (including physical diagnosis) depends on the prevalence of the disorder in the population undergoing the test, a positive test in patients with low prevalence of the disease is more likely to represent a false positive than a true positive (like a positive pregnancy test in a man). This can be extended to the positive predictive values of shifting-dullness and fluid-wave for ascites. Hence, a prominent fluid wave has a high positive predictive value for ascites (96%) in patients with prolonged prothrombin time (PT), but a much lower one (48%) in patients with normal PT. Conversely, absence of shifting dullness makes ascites very unlikely in patients with normal PT (2%). Thus, a focused physical examination based on just two maneuvers (shifting-dullness and fluid-wave) and interpreted in light of patients’ pretest probability of disease (as based on PT) can allow physicians to use ultrasound more judiciously and cost effectively (see Table 15-2)

| Maneuver | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| History | ||

| Increased abdominal girth | 90 | 60 |

| Recent weight gain | 60 | 70 |

| Ankle swelling | 100 | 60 |

| Physical examination | ||

| Bulging flanks | 70 | 60 |

| Flank dullness | 80 | 60 |

| Shifting dullness | 90 | 60 |

| Fluid wave | 60 | 90 |

| Puddle sign | 50 | 70 |

J. The Acute Abdomen (Peritoneal Signs)

enclosed within a fleshy cage,

The symptoms are the actors who

Although they are a motley crew

Who is the author of the play.

That is for you to try and guess

A problem which, I must confess

is made less easy for the fact

You seldom see the opening act,

And by the time that you arrive

Sir Zachary Cope, The Acute Abdomen in Rhyme, 5th ed. London, HK Lewis, 1972

173 What is abdominal hyperesthesia?

It is hypersensitivity (hyperesthesia) to light touch in areas that overlie an inflamed viscus.

174 How can one detect abdominal hypersensitivity?

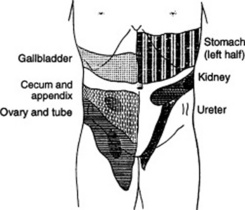

One can easily identify areas of hyperalgesia (increased pain) by lightly drawing across the abdominal wall with a cotton wisp, a pin, or even a fingernail. Head was the first to describe these areas of hypersensitivity. Since then, they have been referred to as Head’s zones (see Fig. 15-19).

K. Special Problems—Appendicitis

183 What is the obturator test?

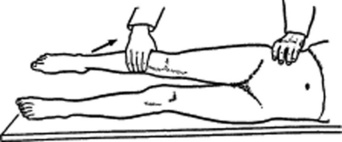

It is a test carried out by asking patients to flex the hip and rotate it internally while lying supine. Examiners can help this movement by pulling the patient’s ankle toward themselves while pushing the knee away. The maneuver should be carried out on both thighs and should remain painless. Pain (usually referred to the suprapubic region) indicates inflammation in one of the organs surrounding the obturator internus muscle and is therefore specific (but poorly sensitive) for retrocaecal appendicitis. The obturator test (see Fig. 15-20 also may be positive in various obstetric-gynecologic conditions of intrapelvic pus; yet in these cases the test is usually positive in both legs, whereas in appendicitis, it is only positive in the right leg.

184 What is the reverse psoas maneuver?

It is another test of irritation of the iliopsoas muscle, either because of retrocaecal appendicitis or some other localized collection of pus and blood. It is performed by having the patient roll toward the left side and hyperextend the right hip (see Fig. 15-21). The test is positive when it elicits pain. Like the obturator test, it has very low sensitivity for appendicitis, but high specificity. Still, given the low sensitivity, both maneuvers are of limited clinical value.

1 Aldea PA, Meehan JP, Sternbach G, et al. The acute abdomen and Murphy’s signs. J Emerg Med. 1986;4:57-63.

2 Arkles LB, Gill GD, Molan MP. A palpable spleen is not necessarily enlarged or pathological. Med J Austr. 1986;145:15-17.

3 Ashby EC. Detecting bladder fullness by subjective palpation. Lancet. 1977;2:936-937.

4 Barkun AN, Camus M, Meagher T, et al. Splenomegaly and Traube’s space: How useful is percussion? Am J Med. 1989;87:562-566.

5 Barkun AN, Camus M, Green L, et al. Bedside assessment of splenic enlargement. Am J Med. 1991;91:512-518.

6 Castell DO, O’Brien KD, Muench H, Chalmers TC. Estimation of liver size by percussion in normal individuals. Ann Intern Med. 1969;70:1183-1189.

7 Castell DO. The spleen percussion sign. Ann Intern Med. 1967;67:1265-1267.

8 Cattau EL Jr, Benjamin SB, Knuff TE, et al. The accuracy of the physical examination in the diagnosis of suspected ascites. JAMA. 1982;247:1164-1166.

9 Chen JJ, Changchien CS, Tai DI, et al. Gallbladder volume in patients with common hepatic duct dilatation: An evaluation of Courvoisier’s sign by ultrasonography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:284-288.

10 Chervu A, Clagett GP, Valentine RJ, et al. Role of physical examination in detection of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surgery. 1995;117:454-457.

11 Chung RS. Pathogenesis of the Courvoisier’s gallbladder. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:33-38.

12 Cummings S, Papadakis M, Melnick J, et al. Predictive value of physical examination for ascites. West J Med. 1985;142:633-636.

13 Dowdall GG. Five diagnostic methods of John B. Murphy of Chicago. Arch Diag. 1910;3:18-21.

14 Espinoza P, Ducot B, Pellettier G. Interobserver agreement in the physical diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:244-247.

15 Gray DW, Dixon JM, Seabrook G, et al. Is abdominal wall tenderness a useful sign in the diagnosis of non-specific abdominal pain? Ann Coll Surg Engl. 1988;70:2333-2334.

16 Gray DW, Dixon JM, Collin J, et al. The closed eyes sign. BMJ. 1988;297:837.

17 Guarino JR. Auscultatory percussion to detect ascites. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1555-1556.

18 Guarino JR. Auscultatory percussion of the bladder to detect urinary retention. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1823-1825.

19 Halpern S, Coel M, Ashburn W, et al. Correlation of liver and spleen size: Determinations by nuclear medicine studies and physical examination. Arch Intern Med. 1974;134:123-124.

20 Kelley ML. Discolorations of flanks and abdominal wall. Arch Intern Med. 1961;108:132-135.

21 Lawson JD, Weissbein AS. The puddle sign—an aid in the diagnosis of minimal ascites. N Engl J Med. 1959;260:652-654.

22 Lederle FA, Simel DL. Does this patient have abdominal aortic aneurysm? JAMA. 1999;281:77-82.

23 Lipp WF, Eckstein EH, Aaron AH, et al. The clinical significance of palpable spleen. Gastroenterology. 1944;3:287-291.

24 Ludwig Courvoisier (1843–1918). Courvoisier’s sign. JAMA. 1968;204:165.

25 McGee S. Percussion and physical diagnosis: Separating myth from science. Disease-a-Month. 1995;41:643-692.

26 McGee S. Evidence-Based Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2001.

27 McLean ACJ. Diagnosis of ascites by auscultatory percussion and hand-held ultrasound. Lancet. 1987;2:1526-1527.

28 Mellinkoff SM. Stethoscope sign. N Engl J Med. 1964;271:630.

29 Meyers MA, Feldberg MA, Oliphant M. Grey Turner’s and Cullen’s sign in acute pancreatitis. GI Radiol. 1989;14:31-37.

30 Naylor CD. Physical examination of the liver. JAMA. 1994;271:1859-1865.

31 Nixon RK. The detection of splenomegaly by percussion. N Engl J Med. 1954;250:166-167.

32 Parrino TA. The art and science of percussion. Hosp Pract. 1987;99:25-36.

33 Ralls PW, Halls J, Lapin SA, et al. Murphy’s sign in cholecystitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1983;21:477-493.

34 Simel DL, Halvorsen RA Jr, Feussner JR, et al. Clinical evaluation of ascites. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:423-428.

35 Tucker WN, Saab S, Rickman LS, et al. Scratch test is unreliable for detecting liver edge. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:410-414.

36 Williams JW, Simel DL. Does this patient have ascites? JAMA. 1992;267:2645-2648.

37 Zoli M, Magalotti D, Grimaldi M, et al. Physical examination of the liver: Still worth it? Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1428-1432.