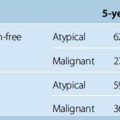

CHAPTER 41 Tentorial and Falcotentorial Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas of the posterior cranial fossa account for about 9% of all intracranial meningiomas.1 Approximately 30% of all posterior fossa meningiomas arise from the tentorium cerebelli.2 The first account of a tentorial meningioma was given by Antral in 1833 as an incidental finding.3 Meningiomas of the falcotentorial junction are considered a subgroup of tentorial meningiomas and constitute about 0.3% to 1.1% of all intracranial meningiomas.4–7 Surgical morbidity and mortality after resection of tentorial/falcotentorial meningiomas have declined steadily as a result of refinements in microsurgical and neuroanesthetic techniques and improved pre- and postoperative patient care. Nonetheless, resection of these tumors remains a major surgical challenge due to their proximity to the brain stem and frequent involvement of critical neurovascular structures, particularly major venous sinuses and the deep venous system.

TENTORIAL MENINGIOMAS

Classification

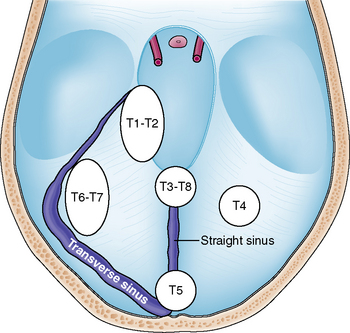

Tumors arising from the tentorium may be confined to the supratentorial or infratentorial compartment or may extend both infra- and supratentorially. Several classification schemes have been proposed for these tumors.8–11 Yaşargil introduced the most accurate of these classifications in regard to surgical anatomy and differentiated among the following tumor subgroups:11 (1) meningiomas arising from the free tentorial notch (i.e., inner ring meningiomas, anterior T1, middle T2, and posterior T3); (2) meningiomas originating from the intermediate tentorial surface (T4); (3) meningiomas involving the torcular herophili (T5); (4) meningiomas arising from the lateral outer tentorial ring (posterior T6, anterior T7); and (5) falcotentorial meningiomas (T8). In our retrospective study of 81 patients harboring a tentorial meningioma and who were treated microsurgically it was usually not possible to accurately differentiate between T1 and T2 and T6 and T7 tumors from preoperative radiologic studies.4 Further, T3 and T8 tumors originate from both the falx and tentorium. Therefore, we consider them, by definition, as falcotentorial meningiomas. For these reasons and for practical purposes, we prefer a modified Yaşargil classification scheme comprising the following tumor subgroups (Fig. 41-1):

Clinical Presentation

Clinical symptoms and signs depend on location and size of the tumor. Patients harboring a lateral tentorium meningioma (T6–T7 subgroup) usually present with headache, dizziness, and gait unsteadiness.4,12 Clinical examination often reveals a gait ataxia and involvement of the VIIIth cranial nerve (CN).4 It may be difficult to differentiate between lateral tentorial and suprameatal posterior petrosal meningiomas on clinical and radiologic grounds.13 The exact origin of the tumor may be recovered only during surgery. Tentorial notch meningiomas (T1–T2 subgroup) usually intimately involve the brain stem. Accordingly, these patients may present with a hemiparesis and impairment of the Vth CN, namely trigeminal neuralgia or facial numbness.14,15 Patients with large tumors may complain of symptoms of raised intracranial pressure due to the accompanying hydrocephalus. Presentation with epileptic fits points to a supratentorial meningioma, which may be in proximity to the medial temporal lobe. Apart from direct involvement of the VIIIth CN, preoperative hearing impairment may also be caused by distortion of central auditory pathways, such as the lateral lemniscus or inferior colliculi.4,16–18 In either case, hearing impairment often shows remarkable improvement after surgery.4,17

Preoperative Considerations and Diagnostic Workup

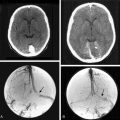

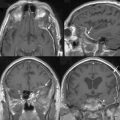

Elderly patients presenting with an incidental finding of a small tentorial meningioma who are asymptomatic or have minor unspecific complaints such as headache or dizziness may best be observed with serial clinical and radiologic follow-up. If the patient becomes symptomatic and/or the tumor is progressive in size, surgical removal may be warranted. Alternatively, radiosurgery may be more appropriate in selected cases, particularly in older patients who are not good surgical candidates due to significant co-morbidity. When surgery is considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with multiplanar images provides the most valuable preoperative diagnostic tool. Computed tomography (CT) scanning, although depicting tumor calcification in some cases, is of minor importance because of its inherent inaccuracy to demonstrate tumors in the posterior cranial fossa and because bone involvement is not a prominent feature in tentorial meningiomas. MRI accurately delineates the location and extent of the tumor. Further, the relationship of the tumor to the basilar artery, for example, displacement or encasement, is demonstrated. Venous sinus patency and the drainage pattern of the Labbé venous complex into the transverse sinus can be nicely depicted from MR venograms (MRV). This information is of particular importance if subtemporal or transpetrous approaches are being considered. Preoperative MR angiography has largely replaced invasive catheter angiography, particularly as embolization of meningiomas in this location is not considered a useful preoperative adjunct.4,18 Hyperintensity of the brain stem adjacent to the tumor on T2-weighted images may point to disrupture of the arachnoid barrier layer and difficulties in microsurgical dissection of the tumor from the brain stem may be anticipated. In our experience, even the most sophisticated preoperative neuroimaging tools available today have important shortcomings. It is usually not possible to exactly define the relationship of the tumor to cranial nerves (integrity, site of displacement, infiltration). Tentorial sinuses usually cannot be visualized on preoperative imaging and may be a source of significant intraoperative bleeding in transtentorial approaches.19 The degree of infiltration of the venous sinus by tumor can be fully appreciated only during surgery. A nonpatent venous sinus on preoperative angiographic studies (MRV or catheter angiography) may prove to be patent during surgery. Finally, information on the functional significance of major venous sinuses or veins is usually lacking.

Surgical Approach and Technique

The primary goal of treatment is complete microsurgical removal of the tumor, including resection of its dural matrix. This is the best means to prevent a tumor recurrence. Of equal importance is preservation of integrity of neurovascular structures and function. The surgical approach should be tailored according to the tumor site and extension (Table 41-1) and should be planned after careful analysis of preoperative radiologic images. Supratentorial tumors of the anterior inner and outer ring, that is, supratentorial T1–T2 and T6–T7 meningiomas, are usually best approached via a subtemporal route. Positioning of the patient’s head to take advantage of gravity and preoperative placement of a lumbar drainage may facilitate temporal lobe retraction. Retraction of the temporal lobe jeopardizes the subtemporal and Labbé venous complex with the potential of major neurologic sequel. Adding a zygomatic osteotomy provides a flatter angle of view to the lesion, resulting in a lesser degree of temporal lobe retraction, but does not completely abandon the risk to the venous system.9,20 Sugita and colleagues have emphasized that preservation of subtemporal veins is facilitated by a wide temporal craniotomy, particularly in horizontal length.10 The venous anatomy should be studied carefully on the preoperative MRV with special attention paid to the drainage site of the temporal veins into the transverse sinus.21 In patients without tumor extension to the upper surface of the petrous bone, a paramedian supracerebellar transtentorial approach has been successfully applied to resect medial tentorial meningioma and avoid the veins of the temporal lobe.22

TABLE 41-1 Location of tentorial meningioma, recommended surgical approaches, and associated potential complications

| Tumor location | Surgical approach | Potential complications* |

|---|---|---|

Modified from Yaşargil’s classification.11

The conventional retrosigmoid approach is suitable for most infratentorial meningiomas of the inner and outer ring (infratentorial T1–T2 and T6–T7 tumors). Alternatively, the supracerebellar infratentorial route via a suboccipital craniotomy may be more appropriate in some more medialized infratentorial T1–T2 tumors. A supratentorial tumor extension in these cases can be removed transtentorially. The supracerebellar infratentorial avenue is the approach of choice in infratentorial paramedian T4 meningiomas. In our experience it was usually sufficient to resect the tumor along with its attachment on the outer dural layer to achieve a Simpson grade 1 resection.4,23 Supratentorial T4 tumors are resected via an occipital approach. Again, a smaller infratentorial tumor portion can be resected transtentorially.24

Complications and Outcome

Surgical mortality and morbidity has steadily declined over the years. Recent microsurgical series report a mortality of 2.5%,4 3.7%,16 0%,14 and 2.7%.12 Surgical morbidity has ranged between 19% and 55% in recent microsurgical series.4,12,14,16 However, most complications were transient and resolved on follow-up.4,16 Postoperative CN morbidity is related to the tumor site and to the approach selected (see Table 41-1). CNs III, IV, and V are endangered during resection of T1–T2 tumors and in the subtemporal and transpetrous approach while CNs VII and VIII are jeopardized in T6–T7 tumors and the retromastoid approach.4 To reduce the incidence of postoperative complications, tumor resection should strictly follow the arachnoid cleavage plane. However, the arachnoid may be disrupted in larger tumors. In these cases, it is preferable to leave a tuft of tumor on critical structures, namely the brain stem, cranial nerves, and blood vessels, to prevent serious neurologic sequel or even surgical fatalities.4

A total tumor removal, defined as a Simpson grade 1 and 2 resection, is reported in 77% to 91% of the patients.4,8,12,14,16 A complete tumor resection is usually achieved in T4 meningiomas, while a total removal is least often feasible in T1–T2 and T5 tumors. A tumor recurrence or progression after subtotal removal is observed in 0% to 26%4,8,12,14–16 in larger series with a long follow-up. A major issue of controversy is whether to resect an infiltrated dural venous sinus to achieve a complete tumor resection and thus decrease the tumor recurrence rate. There is general agreement that a completely occluded sinus can be resected safely.16,25 However, it needs to be remembered that parts of the deep venous system, including venous sinuses, may not be visible on preoperative angiograms, although they are neither occluded nor functionally unimportant.26 In addition, angiograms are prone to underestimate sinus infiltration by tumor.4,8,15 Atresia or septation in the region of the sinus confluence may lead to misinterpretation with regard to dominance of the venous sinus.27 Current data in the literature do not demonstrate a lower tumor recurrence rate in series in which aggressive resection of involved venous sinuses was performed.8,12,15 Further, it has been demonstrated that subtotal removal of meningioma can be associated with a long-progression-free period and high quality of life.28 We therefore recommend preservation of an infiltrated but patent dural venous sinus and have performed either resection of the infiltrated outer dural layer of the sinus or careful coagulation of residual tumor on the sinus wall with low bipolar current. Stereotactic radiosurgery may be a useful treatment option for patients with residual or recurrent tentorial meningiomas. A recent small series using stereotactic radiosurgery in recurrent or incidental tentorial meningiomas reported an overall tumor control rate of 98% after a mean follow-up period of 3 years.29

FALCOTENTORIAL MENINGIOMAS

Location and Classification

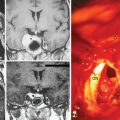

Falcotentorial meningiomas arise from the dura of the tentorium and posterior part of the falx cerebri. They extend into the pineal region and account for 2% to 8% of all tumors located in this area.1,5,30 Rarely, meningiomas occupying the pineal region or the posterior part of the third ventricle have no dural attachment.31–33 These tumors are supposed to arise from the velum interpositum of the third ventricle and can be distinguished from true falcotentorial meningiomas in that they displace the galenic venous complex posteriorly and receive their main blood supply from the medial and lateral posterior choroidal arteries.31,32,34 True falcotentorial meningiomas are mainly supplied by the tentorial branch of the meningohypophyseal trunk.35,36 Several classification systems were proposed for these tumors.7,35–37 All classification systems consider the relationship of the tumor to the vein of Galen, which may either be dislocated superiorly or displaced inferiorly by the tumor. In addition, some falcotentorial meningiomas displace the galenic venous system to one side, a fact that should be appreciated when planning the surgical approach. We have proposed a classification system that takes into account the origin and direction of growth of the tumor as revealed from preoperative MR imaging.36 These considerations give the most important clue to the displacement of the galenic venous system and help in selecting the most appropriate approach. As depicted in Table 41-2, four tumor subtypes were differentiated.

TABLE 41-2 Types of falcotentorial meningioma and preferred surgical approach

| Tumor type | Tumor origin and location of Galenic venous system | Surgical approach |

|---|---|---|

| I | Origin between leafs of the falx, above junction of the vein of Galen and straight sinus. Displaces the vein of Galen inferiorly. | Occipital transfalcine (transtentorial) |

| II | Origin from underneath the tentorium near junction of vein of Galen with straight sinus thus elevating the Galenic venous system. | Infratentorial supracerebellar |

| III | Origin from paramedian tentorial incisura, hence lateralized. Vein of Galen on the medial aspect of the tumor. | Occipital (transtentorial) |

| IV | Origin from the FT junction along the straight sinus. Pushes the Galenic venous system contralaterally. | Occipital |

Clinical Presentation

The most common presenting symptom is headache, which is reported in 60% to 100% of all patients.5,7,35–38 Headache and mental changes, the latter being reported in up to 46% of patients, are frequently associated with concomitant obstructive hydrocephalus. On clinical examination, the most frequent findings are gait ataxia and a homonymous field defect, present in 43% to 62%5,7,35,36 and 20% to 46%7,36–40 of the patients, respectively. There was a close association between clinical signs and tumor type;36 most patients with a type I and II tumor revealed a gait ataxia, a hemiparesis was commonly associated with a paramedian type III tumor and a homonymous hemianopsia, usually irreversible, was observed in all patients harboring a type IV tumor.36 Infrequently reported symptoms and signs, such as upward gaze paresis, tinnitus and hypacusis may show amelioration or even complete resolution after surgical removal of the tumor.5,17,36,38–44

Preoperative Neuroimaging

As is the case in other tentorial meningiomas, MR imaging combined with MR angiography is the diagnostic tool of choice for preoperative workup. Beside tumor location (infra-supratentorial) and extension, preoperative analysis should particularly focus on patency of the straight sinus and patency and site of dislocation of the galenic venous system. Location of the galenic venous system mainly directs the surgical approach. An occlusive type of hydrocephalus is present in up to 54% of the patients and should be treated before or at the time of tumor resection.7,35,36,45,46 At our institution, catheter angiography is no longer performed as part of the preoperative workup in these tumors.

Surgical Strategy

Araki, in 1937, reported the first successful removal of a pineal region meningioma in 2 patients via a transcallosal approach.47 Two other surgical approaches are more routinely adopted in the treatment of pineal region tumors, namely the occipital transtentorial and the infratentorial supracerebellar approach. The transtemporal transventricular approach originally described by Van Wagenem in 1931 has not gained wide acceptance and is of historical interest only.48

The most commonly used surgical approach for falcotentorial meningiomas is the occipital transtentorial avenue, which was first proposed by Tandler and Ranzi in 1920 and first successfully performed by Foerster in 1923 in a patient harboring a cystic pineal tumor.49,50 Poppen reviewed this approach in 1966.51 All type I, type II, and most type III meningiomas can be removed using this surgical route.36 An occipital bone flap is fashioned on the side of the main bulk of the tumor to expose the superior sagittal sinus medially and the transverse sinus inferiorly. In symmetric tumors, a right occipital craniotomy is preferred. Concomitant obstructive hydrocephalus may be relieved by cannulating the occipital horn, a technique already applied by Foerster.49 This maneuver facilitates smooth retraction of the occipital lobe. After opening the dura, the dissection is directed along the falcotentorial angle toward the posterior tentorial notch where type I meningiomas are encountered. An advantage of this approach is the paucity of medial bridging veins between the occipital lobe and the superior sagittal sinus; however, there is a risk of mechanical and/or ischemic injury of the calcarine area with subsequent postoperative homonymous hemianopia. Traditionally, the approach includes incision of the tentorium 1 cm paramedian and parallel to the straight sinus.49,51,52 This step proved to be useful in patients with a steep tentorium but should not be performed on a routine basis.36 The tentorium may contain prominent venous sinuses, which may be a source of troublesome bleeding.19,44 These channels may also serve as collateral venous drainage in cases in which the straight sinus and/or vein of Galen are occluded.19,53 In type I meningiomas, the posterior part of the falx including the posterior end of the inferior sagittal sinus can safely be resected to access the contralateral tumor portion and to resect the tumor origin in between the leafs of the falx.

The infratentorial supracerebellar approach was first successfully applied by Krause in 1913 and was reemphasized by Stein in 1971.54,55 This approach usually includes sacrifice of the precerebellar and superior vermian veins which is usually well tolerated.55–57 The infratentorial, supracerebellar route is well suited for an infratentorial falcotentorial meningioma that has elevated the galenic venous complex (type II tumor). However, surgical access to lateral or supratentorial tumor extensions is limited and may in addition require an occipital supratentorial approach. This may also be required if removal of the tumor is hampered by dense adhesions to the galenic venous system. Limited supratentorial tumor portions can be removed via the supracerebellar transtentorial modification.58

The parietal transcallosal interhemispheric approach was first performed by Brunner in 1912.59 This approach was successfully applied and propagated by Dandy.45 Splitting of the posterior corpus callosum over a length of 4 cm apparently had no psychological sequel in the cases of Brunner and Dandy.45,59 However, more recent detailed postoperative neuropsychological studies disclosed a disconnection syndrome after removal of a huge falcotentorial meningioma via the transcallosal approach.60 Further, it may be difficult to visualize the galenic venous system, particularly when the veins are depressed by the tumor. Care must be taken to spare the superficial bridging veins when performing this approach.

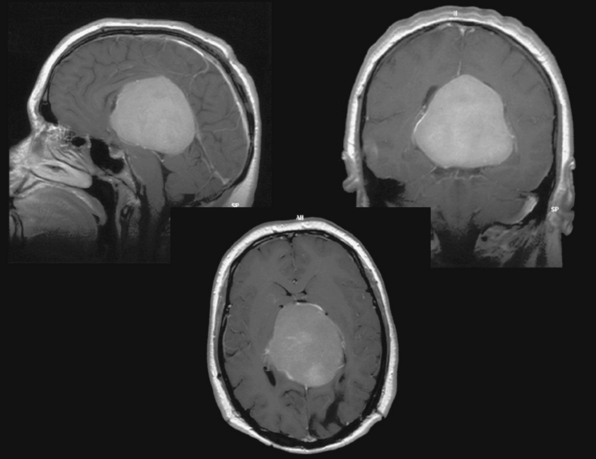

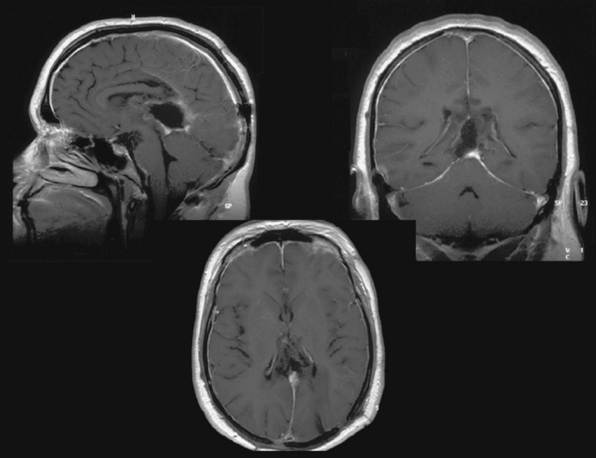

Several modifications of these basic approaches have been described and may be considered in selected cases; Pussep,61 in 1910 performed a combined supra–infratentorial transsinus approach to resect a pineal tumor. His patient survived for only 3 days. Sekhar and Goel44 reconsidered this approach in 1992 and successfully applied it in four patients harboring a tentorial meningioma. The approach entails detailed preoperative angiographic studies to determine dominance of the transverse sinus as well as intrasinusoidal pressure measurement with test occlusion of the sinus during surgery. The reconstructed transverse sinus was shown to be patent on postoperative MRI in their study.44 Figures 41-2 to 41-4 illustrate a giant falcotentorial/pineal region meningioma operated on by us via the combined supra–infratentorial approach with sectioning of the transverse sinus. Kawashima and colleagues53 have recommended an occipital bitranstentorial/falcine approach to maximally enhance vision of the pineal region. This approach avoids a bilateral occipital craniotomy but may increase the risk of bilateral visual compromise. Tamaki and Yin have proposed a combined infratentorial supracerebellar and occipital transtentorial approach.62

Complications and Outcome

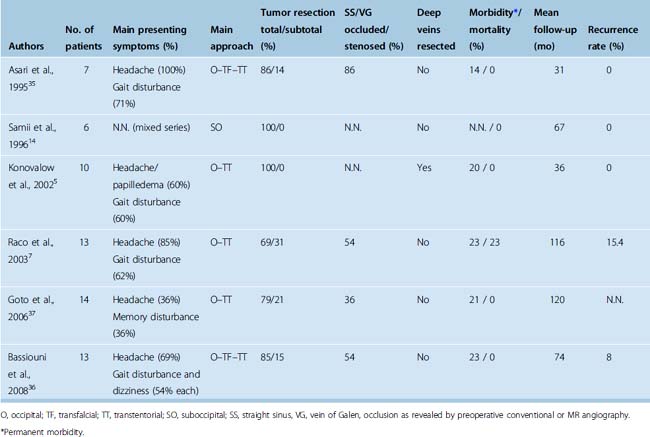

Surgery of pineal region tumors was once associated with a high morbidity and mortality rate. The risk of surgery in this complex area was greatly reduced due to advances in microsurgical technique and preoperative neuroimaging and refined neuroanesthetic methods (Table 41-3). Recent microsurgical series of falcotentorial meningiomas report a mortality rate of 0 to 23%5,7,14,35–37 and a permanent morbidity rate of 14% to 29%.5,7,35–37 An inherent risk of the occipital interhemispheric approach is postoperative homonymous hemianopia.5,35–38,46,63 This complication seems to be primarily due to prolonged occipital lobe retraction and should thus be preventable. Excessive retraction and static pointed pressure of the spatula on the medial occipital lobe should be avoided to prevent vascular compromise of the calcarine area. Further, the internal occipital vein, which may cross the surgical field, drains the calcarine area and should be preserved during preparation.

Most recent microsurgical series report a total tumor resection rate (Simpson grade 1 and 2) of 70% to 90%.7,35–37 Adherence of the tumor to the deep venous system, particularly the great vein of Galen, is the most frequent cause for incomplete tumor removal.6,7,15,35,37,64 Some authors have advocated resection of occluded parts of the galenic venous system as demonstrated on preoperative angiographic studies.5,26 Indeed, resection of compromised parts of the galenic venous system has been performed in several instances without apparent adverse neurologic sequelae.5,26,43,65,66 However, patency of the straight sinus not visualized on preoperative angiographic studies has been demonstrated during surgery7,36 and poor or even fatal outcomes after deep venous resection are reported.1,5,45,67,68 Again, it cannot be concluded from current literature data, that radical tumor removal along with infiltrated parts of the deep veins results in a lower tumor recurrence rate.5,7,14,35–37,68 We therefore recommend preservation of the straight sinus and Galenic venous system. Residual or recurrent tumors may respond well to adjuvant radiosurgery;6,7,69 however, literature data on this topic are too scarce to draw a final conclusion.

[1] Castellano F., Ruggiero G. Meningiomas of the posterior fossa. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1953;104:1-177.

[2] Quest D.O. Meningiomas: An update. Neurosurgery. 1978;3:219-225.

[3] Yaşargil M.G., Mortara R.W., Curcic M. Meningiomas of the basal posterior cranial fossa. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1980;7:3-115.

[4] Bassiouni H., Hunold A., Asgari S., Stolke D. Tentorial meningioma: Clinical results in 81 patients treated microsurgically. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:108-118.

[5] Konovalov A.N., Spallone A., Pitzkhelauri D.I. Meningioma of the pineal region: a surgical series of 10 cases. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:586-590.

[6] Okami N., Kawamata T., Hori T., et al. Surgical treatment of falcotentorial meningioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2001;8(Suppl. 1):15-18.

[7] Raco A., Agrillo A., Ruggeri A., et al. Surgical options in the management of falcotentorial meningiomas: Report of 13 cases. Surg Neurol. 2004;61:157-164.

[8] Guidetti B., Ciappetta P., Domenicucci M. Tentorial meningiomas: surgical experience with 61 cases and long-term results. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:183-187.

[9] Sen C. Surgical approaches to tentorial meningiomas. In: Wilkins R.H., Rengachary S.S., editors. Neurosurgery. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996:917-924.

[10] Sugita K., Suzuki Y. Tentorial meningiomas. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:357-361.

[11] Yaşargil M.G. Meningiomas. Yaşargil M.G., editor. Microneurosurgery, vol. IVB. Thieme, New York, 1996;134-157.

[12] Gökalp H.Z., Arasil E., Erdogan A., Egemen N., Deda H., Cerci A. Tentorial meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:46-51.

[13] Bassiouni H., Hunold A., Asgari S., Stolke D. Meningiomas of the posterior petrous bone: Functional outcome after microsurgery. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:1014-1024.

[14] Samii M., Carvalho G.A., Tatagiba M., Matthies C., Vorkapic P. Meningiomas of the tentorial notch: surgical anatomy and management. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:375-381.

[15] Sekhar L.N., Jannetta P.J., Maroon C.J. Tentorial meningiomas: surgical management and results. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:268-275.

[16] Bret P.H., Guyotat J., Madarassy G., Ricci A.C., Signorelli F. Tentorial meningiomas. Report of twenty-seven cases. Acta Neurochir. 2000;142:513-526.

[17] DeMonte F., Zelby A.S., Al-Mefty O. Hearing impairment resulting from a pineal region meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:665-668.

[18] Harrison M.J., Al-Mefty O. Tentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurosurg. 1997;44:451-466.

[19] Matsushima T., Suzuki S.O., Fukui M. Microsurgical anatomy of the tentorial sinuses. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:923-928.

[20] Al-Mefty O. Supraorbital-pterional approach to skull base lesions. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:474-477.

[21] Sakata K., Al-Mefty O., Yamamoto I. Venous consideration in petrosal approach: microsurgical anatomy of the temporal bridging vein. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:153-160.

[22] Uchiyama N., Hasegawa M., Kita D., Yamashita J. Paramedian supracerebellar transtentorial approach for a medial tentorial meningioma with supratentorial extension: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1470-1474.

[23] Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22-39.

[24] Rostomily R.C., Eskridge J.M., Winn H.R. Tentorial meningiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1994;5:331-348.

[25] Harsh IV G.R., Wilson C.B. Meningiomas of the peritorcular region. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:363-369.

[26] Odake G. Meningioma of the falcotentorial region: report of two cases and literature review of occlusion of the galenic system. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:788-794.

[27] Bisaria K.K. Anatomic variations of the venous sinuses in the region of the torcular Herophili. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:90-95.

[28] Ciric I., Landau B. Tentorial and posterior cranial fossa meningiomas: Operative results and long-term follow-up: experience with twenty-six cases. Surg Neurol. 1993;39:530-537.

[29] Muthukumar N., Konziolka D., Lunsford L.D., Flickinger J.C. Stereotactic radiosurgery for tentorial meningiomas. Acta Neurochir. 1998;140:315-321.

[30] Obrador S., Soto M., Gutierrez-Diaz J.A. Surgical management of tumours of the pineal region. Acta Neurochir. 1976;34:159-171.

[31] Madawi A.A., Crockard H.A., Stevens J.M. Pineal region tumors without dural attachment. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10:305-307.

[32] Roda J.M., Perez-Higueras A., Oliver B., et al. Pineal region meningiomas without dural attachment. Surg Neurol. 1982;17:147-151.

[33] Sachs E., Avman N., Fisher R.G. Meningiomas of pineal region and posterior part of 3rd ventricle. J Neurosurg. 1962;19:325-331.

[34] Rozario R., Adelman L., Prager R.J., et al. Meningiomas of the pineal region and third ventricle. Neurosurgery. 1979;5:489-495.

[35] Asari S., Maeshiro T., Tomita S., et al. Meningiomas arising from the falcotentorial junction. Clinical features, neuroimaging studies, and surgical treatment. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:726-738.

[36] Bassiouni H., Asgari S., König H.-J., Stolke D. Meningiomas of the falco-tentorial junction: Selection of the surgical approach according to the tumor type. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:339-349.

[37] Goto T., Ohata K., Morino M., et al. Falcotentorial meningioma: surgical outcome in 14 patients. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:47-53.

[38] Piatt H.J., Campell G.A. Pineal region meningioma: Report of two cases and literature review. Neurosurgery. 1983;12:369-376.

[39] Gross S.W., Levin P. Meningioma of the falx-tentorial angle with successful removal: A case report. J Mount Sinai Hospital. 1965;32:9-16.

[40] Nishiura I., Handa H., Yamashita J., et al. Successful removal of a huge falcotentorial meningioma by use of the laser. Surg Neurol. 1981;16:380-385.

[41] Ameli N.O., Armin K., Saleh H. Incisural meningiomas of the falco-tentorial junction. J Neurosurg. 1966;24:1027-1030.

[42] Ausman J.I., Malik G.M., Dujovny M., et al. Three-quarter prone approach to the pineal-tectorial region. Surg Neurol. 1988;29:298-306.

[43] Sakaki S., Shiraishi T., Takeda S., et al. Occlusion of the great vein of Galen associated with a huge meningioma in the pineal region. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:1136-1140.

[44] Sekhar L.N., Goel A. Combined supratentorial and infratentorial approach to large pineal-region meningioma. Surg Neurol. 1992;37:197-201.

[45] Dandy W.E. An operation for the removal of pineal tumors. Surg Gyn Obst. 1921;33:113-119.

[46] Papo I., Salvolini U. Meningiomas of the free margin of the tentorium developing in the pineal region. Neuroradiology. 1974;7:237-243.

[47] Araki C. Meningioma in the pineal region. A report of two cases removed at operation. Arch Jap Chir. 1937;14:1181-1192.

[48] Van Wagenem W.P. A surgical approach for the removal of certain pineal tumors. Surg Gyn Obst. 1931;53:216-220.

[49] Foerster O. Das operative Vorgehen bei Tumoren der Vierhuegelgegend. Wien Klin Wchnschr. 1928;28:986-990.

[50] Tandler J., Ranzi E. Chirurgische Anatomie und Operationstechnik des Zentralnervensystems. Berlin: Springer, 1920.

[51] Poppen J.L. The right occipital approach to a pinealoma. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:706-710.

[52] Clark W.K., Batjer H.H. The occipital transtentorial approach. In: Apuzzo M.L.J., editor. Surgery of the Third Ventricle. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:721-741.

[53] Kawashima M., Rhoton A.L., Matsushima T. Comparison of posterior approaches to the posterior incisural space: Microsurgical anatomy and proposal of a new method, the occipital bi-transtentorial/falcine approach. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1208-1221.

[54] Oppenheimer H., Krause F. Operative Erfolge bei Geschwülsten der Sehhügel- und Vierhügelgegend. Berl Klin Wochenschr. 1913;50:2316-2322.

[55] Stein B.M. The infratentorial supracerebellar approach to pineal lesions. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:197-202.

[56] Quest D.O., Kleriga E. Microsurgical anatomy of the pineal region. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:385-390.

[57] Reid W.S., Clark W.K. Comparison of the infratentorial and transtentorial approaches to the pineal region. Neurosurgery. 1978;3:1-8.

[58] Voigt K., Yaşargil M.G. Cerebral cavernous haemangiomas or cavernomas. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg). 1976;19:59-68.

[59] Rorschach H. Zur Pathologie und Operabilität der Tumoren der Zirbeldrüse. Bruns Beitr. 1913;83:451-574.

[60] Suzuki M., Sobata E., Hatanaka M., et al. Total removal of a falcotentorial junction meningioma by biparietooccipital craniotomy in the sea lion position: A case report. Neurosurgery. 1984;15:710-714.

[61] Pussep L. Die operative Entfernung einer Zyste der Glandula pinealis. Neurol Centralbl. 1914;113:560-568.

[62] Tamaki N., Yin D. Combined infratentorial and supratentorial transtentorial approach to pineal region tumors. A technical note. Neurosurg Q. 1999;9:236-240.

[63] Nazzaro J.M., Shults W.T., Neuwelt E.A. Neuro-ophthalmological function of patients with pineal region tumors approached transtentorially in the semisitting position. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:746-751.

[64] Matsuda Y., Inagawa T. Surgical removal of pineal region meningioma – Three case reports –. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1995;35:594-597.

[65] Malluci C.L., Obukhov S. Successful removal of large pineal region meningiomas. Two case reports. Surg Neurol. 1995;44:562-566.

[66] Seeger W. Microsurgery of cerebral veins. New York: Springer, 2000.

[67] Heppner F. Meningioma of the third ventricle. Acta Neurochir. 1954;4:55-67.

[68] Pendl G. Management of pineal region tumors. Neurosurg Q. 2002;12:279-298.

[69] Kondziolka D., Lundsford D. Radiosurgery of meningiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1992;3:219-230.