86 Tendinitis and Bursitis

• Emergency department treatment of tendinopathy and aseptic bursitis should be initiated conservatively with rest, immobilization of the involved tendon, compression of superficial bursae, and oral analgesia.

• Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs may be useful in providing pain relief for patients with tendinopathy and bursitis but are no longer preferred over other analgesic regimens.

• Other emergency medical conditions such as septic arthritis, suppurative tenosynovitis, septic bursitis, fractures, and rheumatologic conditions should be excluded in the differential diagnosis.

Epidemiology

The incidence of tendinitis increases with age as muscles and tendons lose some of their elasticity, and it is highest in the age group 25 to 54 years. Bursitis affects approximately 1 in 31 (3.2%) or 8.7 million people in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2001 tendinitis was responsible for a median of 10 days away from work as compared with 6 days for all cases of nonfatal injury and illness.1 Most cases of tendinitis involved white, non-Hispanic women whose occupations had a highly repetitive component.

Pathophysiology

Most often, tendon injury is caused by chronic overuse resulting in degenerative changes.2,3 The classic inflammatory signs of pain, warmth, erythema, and swelling may sometimes be experienced acutely, although tendinitis is no longer thought to be an inflammatory disorder.4 Bursae may become inflamed for many reasons: chronic friction, trauma, crystal deposition, infection, and systemic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, tuberculosis, and gout). Because tendons frequently cross over bursae, it is not uncommon for bursitis to be secondary to overlying tendonitis (e.g., supraspinatus tendinitis, subacromial bursitis).

Tendonitis

The signs and symptoms of tendinitis can be quite variable. Pain is the most common complaint of patients with joint problems seen in the ED. Particular attention should be paid to the location of the pain; it can be articular (within the joint capsule), as in septic arthritis, or periarticular (outside the joint capsule), as in tendinitis or bursitis (Table 86.1).

Table 86.1 Clinical Features of Articular versus Periarticular Joint Pain

| CLINICAL FEATURE | ARTICULAR | PERIARTICULAR |

|---|---|---|

| Associated conditions | Septic or other arthropathies | Tendinitis and bursitis |

| Range of motion | Decreased | Preserved |

| Pain | With passive and active motion | Only with certain active movements |

| Fever | Yes | No* |

| Trauma | Fractures | Repetitive use or stress |

| Risk factors | Rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, crystal arthropathy | Corticosteroid or fluoroquinolone use, connective tissue disease |

| Association with rest | Morning stiffness improves throughout the day | Night pain prevents sleep |

* Exceptions are septic bursitis and suppurative tenosynovitis.

Bursitis

Inflammation of a bursa may be infectious or traumatic, degenerative, or due to underlying systemic disease.5 Risk factors for the development of bursitis are acute trauma, repetitive injury to the painful area, infections, tuberculosis, gout, pseudogout, uremia, and rheumatoid arthritis. The diagnosis is made clinically based on tenderness at a bursal site, swelling of a superficial bursa, and localized pain with motion and at rest. Regional loss of active motion may occur as a result of swelling; however, range of motion should not be affected in patients with aseptic bursitis (see the Red Flags box on tendinopathy and bursitis).

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Tendinopathy and Bursitis

Any joint effusion with systemic symptoms is septic arthritis until proved otherwise.

Any injury in a patient with a history of trauma is considered a fracture until proved otherwise.

Pain with passive motion indicates joint involvement; further investigation for an inflammatory or infectious cause is needed.

A history of steroid injection into a large tendon greatly increases the risk for rupture.

Steroid injections or systemic steroids increase the risk for infection.

Fluoroquinolone use increases the risk for tendonitis and tendon rupture.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Shoulder

Supraspinatus Tendinitis/Impingement Syndrome

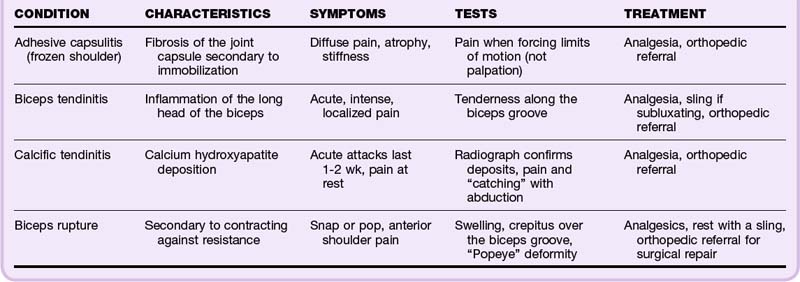

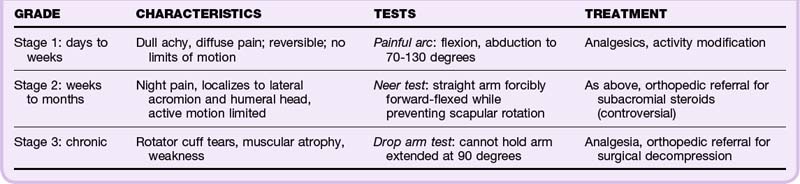

Because of its complex structure and extensive range of motion, the shoulder is a joint predisposed to overuse injuries. The muscles of the rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis) and the glenohumeral ligaments serve to stabilize the joint. Impingement of these tendons occurs because of their position between the humeral head and acromion, which predisposes to chronic tendinosis6,7 (Table 86.2). Impingement syndrome is the number one cause of shoulder pain. It occurs in three progressive stages that worsen over time. Testing and staging of impingement syndrome are reviewed in Table 86.3.

Subacromial Bursitis

The subacromial bursa lies under the acromion and coracoacromial ligament, to which it is attached. This bursa separates the ligament from the supraspinatus muscle and rotator cuff. Subacromial bursitis is thus thought to be an extension of supraspinatus tendinitis and typically follows this disorder’s stages of impingement. Pain and tenderness are localized to the lateral aspect of the shoulder, and signs of impingement are noted on physical examination (see Table 86.3).

Elbow

Lateral and Medial Epicondylitis

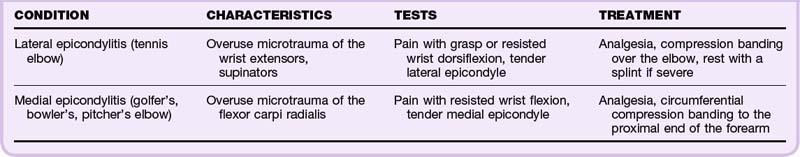

The lateral and medial epicondyles are commonly injured as a result of repetitive use (Table 86.4). Pain often begins as a dull ache that increases with the inciting activity. Approximately 50% of tennis players will experience lateral epicondylitis, although less than 5% of those with the syndrome play tennis. Radiographs may be helpful in atypical or prolonged cases to exclude rare pathologic conditions such as tumors.8

Wrist and Hand

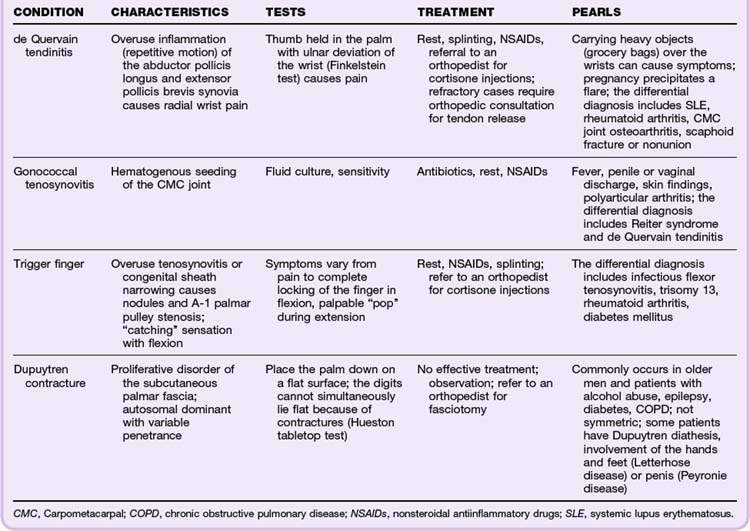

The wrist and hand are composed of several tendons that pass through thick, fibrous retinacular tunnels. Overuse syndromes are thought to result from degenerative changes in the synovial lining between these tendons and the retinaculum (Table 86.5).

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Suppurative Tenosynovitis

Infection of the closed synovial sheaths of the flexors (rarely extensors), often of the fingers and hand

Usually caused by trauma, with the type of bacteria depending on the traumatic exposure (bite wound, puncture, skin flora)

Kanavel signs: tenderness over the flexor sheath, symmetric swelling of the digit, slightly flexed finger at rest, pain with passive extension of the finger

Additional signs: local erythema, edema, lymphangitic streaking, fever, leukocytosis

Treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, admission to the hospital, emergency surgical evaluation for incision and drainage

Prophylaxis of all bite wounds recommended to prevent flexor tenosynovitis

Knee

Prepatellar Bursitis

Prepatellar bursitis (housemaid’s knee, nun’s knee) causes visual swelling over the lower pole of the patella. Range of motion may increase the pain as the bursa is placed under tension. Findings on examination of the joint are usually normal. Pyogenic prepatellar bursitis is an infection of this bursa and is common in children. This condition requires aspiration, immobilization, and antibiotic coverage. If acute episodes are not resolved within 2 days, incision and drainage should be considered.9

Infrapatellar Bursitis

The infrapatellar bursa is divided into two parts. Between the patellar ligament and the superior anterior surface of the tibia lies the deep part. The superficial aspect lies between the skin and patellar ligament. Deep infrapatellar bursitis is associated with tenderness on both sides of the tendon that increases with extreme flexion.10

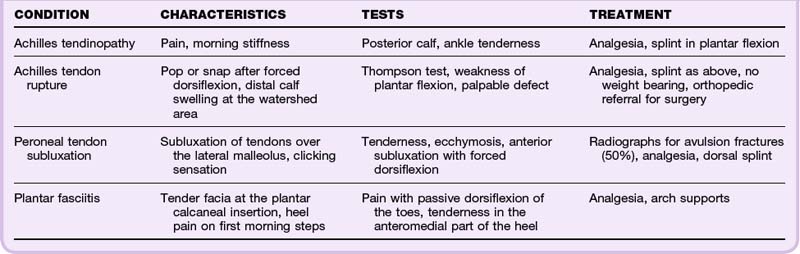

Ankle

Achilles Tendinitis

The Achilles tendon can be injured as a result of direct trauma, overuse, and medications such as steroids or fluoroquinolones11 (Table 86.6; also see the Red Flags box on fluoroquinolones and tendinopathy). It can also become inflamed as part of a systemic disease (ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome, gout, pseudogout). However, most causes of Achilles tendinitis are thought to be multifactorial. Additionally, the vascular supply creates a watershed area approximately 2 to 6 cm above the calcaneal insertion and is thought to be responsible for the clinical symptoms and pathologic disruption at this site. Tendon rupture must be ruled out. Diagnosis and treatment of Achilles tendon rupture are discussed further in Chapter 85.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Fluoroquinolones and Tendinopathy

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a black box warning for all fluoroquinolone antibiotics because of the increased risk for tendinopathy and tendon rupture.

Risks are increased in patients older than 60 years, those taking corticosteroids, and transplant recipients.

Patients prescribed fluoroquinolones should be advised to stop the medication at the first sign of pain, swelling, or inflammation in a tendon area and to avoid exercise and use of the area.

Signs of tendon rupture include an audible snap or pop, immediate bruising, and loss of motor function or inability to bear weight in the area.

Initial conservative treatment includes pain control, splinting in plantar flexion, and referral to orthopedics for stretching, eccentric load strength training, and correction of limb misalignment with orthotics. Surgical referral is urgent if there is any concern for tendon rupture.12

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of tendonitis and aseptic bursitis is related to the clinical features accompanying the patient’s joint pain (see Table 86.1). Febrile patients need evaluation for septic bursitis and septic joints. Additional differential diagnostic considerations include inflammatory arthritis and gout. If multiple joints are involved and the swelling is symmetric, viral infection, drug-induced reaction, and osteoarthritis should be considered. If the joint swelling is asymmetric, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and serum sickness should be considered. If a characteristic rash is present, rheumatologic diseases, Reiter syndrome, Lyme disease, and dermatomyositis should be considered. If the pain is migratory, one should consider gonococcal disease and rubella. If the pain occurred after trauma and a joint effusion is present, hemarthrosis is a possibility. If an audible “pop” is heard, tendon rupture should be considered. If no joint effusion is present, one should look for radiographic evidence of fracture.

Diagnostic Testing

Patients with bursitis who have local signs of inflammation or any systemic symptoms should be evaluated for septic bursitis (see the Red Flags box on septic bursitis). Some distinguishing characteristics of septic bursitis are rapid onset, marked warmth, erythema, and extremely tense and painful bursae. The most commonly infected bursae are those most superficial: the olecranon and the prepatellar and superficial infrapatellar bursae. Bursae are most often directly inoculated with Staphylococcus aureus as a result of subcutaneous trauma. Hematogenous spread of infection is rare. If a deep bursa becomes infected, it is probably due to contiguous cellulitis or septic arthritis.5

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Septic Bursitis

Erythema, edema, pain, or adjacent cellulitis over a bursa is a possible indication of septic bursitis.

Patients with septic bursitis may have fever, leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or neutrophilic bandemia, although systemic findings are not universal and are more common with deep bursa infection.

Joint mobility may be preserved if no direct joint involvement is present.

Any swollen bursa with signs of infection should be aspirated and sent for culture and Gram stain.

Eighty percent of cases of bacterial septic bursitis are due to Staphylococcus aureus; the rest are due mostly to β-hemolytic streptococci.

Antibiotic coverage should cover staphylococcal and streptococcal species, preferably guided by Gram stain results.

Empiric choices for outpatients include dicloxacillin and clindamycin (with or without trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for patients at risk for methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Empiric intravenous antibiotic choices include cefazolin or vancomycin.

The duration of therapy is between 1 and 4 weeks, depending on culture results and response to treatment.

Any patient with severe inflammation, systemic signs, diabetes, or immunosuppression should be admitted for intravenous antibiotics and consultation with orthopedics for incision and drainage.

Gram stain, culture, crystal analysis, and a bursal white blood cell (WBC) count should be obtained. Because systemic leukocytosis is neither sensitive nor specific, a routine complete blood count can be omitted. A bursal fluid WBC count higher than 5000/mm3 suggests bursal fluid infection; however, this may not be clear-cut because of overlap in the WBC count of bursa fluid in septic versus aseptic cases (synovial fluid analysis is discussed in more detail in Chapter 107). Therefore, if infection is suspected, regardless of the Gram stain results, treatment with antistaphylococcal antibiotics should be instituted pending culture results.

Imaging Studies

A diagnosis of tendinitis or bursitis is generally made on clinical grounds, but radiologic studies are sometimes required to confirm the diagnosis by ruling out other causes of pain. Plain radiographs help distinguish extraarticular from articular sources of pain.13 In acute injury, radiographs are essential to exclude an avulsion fracture. Ultrasonography is useful in the evaluation of joint effusions and lesions involving tendons, ligaments, and skeletal muscles. It can be very helpful in guiding difficult joint aspirations in the ED and is particularly useful in imaging of the shoulder region.14 Ultrasound has been shown to be more sensitive than magnetic resonance imaging and is now considered the “gold standard” for evaluating tendon involvement with concomitant trauma or rheumatic diseases.

Treatment

Most patients seen in the ED with tendinopathy can be managed conservatively by resting the affected region, administering adequate pain medication, and referral to orthopedics or physical therapy for biomechanical rehabilitation and gradual eccentric load exercises (Box 86.1). Aseptic bursitis can be managed conservatively with joint protection, modification of activity, and pain control. Exceptions are olecranon bursitis and prepatellar bursitis, which have a moderate risk of being infected, most likely with S. aureus. These bursae require needle aspiration and treatment with antibiotics until culture results are negative. Documentation should support the clinical suspicion of infection (see the Documentation box).

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) provide pain relief when compared with placebo and are well ingrained in the literature as treatment of both tendinopathy and bursitis. Because tendinopathies are now thought to be due to degenerative changes and abnormal healing responses, NSAIDs may not provide any additional benefit over other oral analgesics such as acetaminophen.15 NSAIDs have not been found to improve healing in patients with chronic tendinopathy and probably should not be used long-term for the management of recurrent pain.4 Further research is needed in this area. Oral analgesia should therefore be tailored to the patient. Regardless of the medication chosen, a short (1- to 2-week) course of oral analgesia should be administered as first-line treatment along with rest and modification of activity.

Glucocorticoid injections are often used in treating refractory rotator cuff tendonitis, de Quervain tendonitis, trigger finger, subacromial bursitis, trochanteric bursitis, and olecranon bursitis, although good-quality research to support their use is lacking.4,16 Complications of intrabursal injections are infection, local subcutaneous atrophy, bleeding, postinjection flare as a result of the release of microcrystals, and tendon rupture. Steroid injections are best managed by the follow-up physician after conservative measures have failed and culture results have definitively ruled out infection.

Multiple alternative treatments of chronic tendinopathy exist as well, including massage, stretching, cryotherapy, heat, therapeutic ultrasound, laser, orthotics, and various types of tendon injections. Evidence to support the use of these treatments is lacking.4,17,18 Some evidence supports eccentric load rehabilitation exercises for the treatment of chronic tendinopathy.4

Admission and Discharge

Most patients can be managed conservatively as outpatients as long as close follow-up is ensured (see the Patient Teaching Tips box). Referral to the primary medical physician, orthopedic surgery, and physical therapy is appropriate. Patients who undergo fluid aspiration of bursitis should follow up within 48 hours for culture results. Otherwise, patients may schedule follow-up within 1 to 2 weeks so that further treatment can be initiated if conservative measures fail. Patients with suppurative tenosynovitis or septic bursitis require admission for intravenous antibiotics and consultation with orthopedic surgery for incision and drainage.5

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Instructions should be given regarding proper rest, analgesia, and immobilization.

If a joint or bursa is aspirated, prompt follow-up must be obtained for culture results.

Septic bursitis requires antistaphylococcal antibiotics and immediate orthopedic consultation. Patients with systemic symptoms require admission for intravenous antibiotics and operative washout.

Patients should call their primary provider or return to the emergency department for the following:

Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG. Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1404–1410.

Rees JD, Wilson AM, Wolman RL. Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology. 2006;45:508–521.

Small LN, Ross JJ. Suppurative tenosynovitis and septic bursitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:991–1005.

1 National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Worker health chartbook. No. 2004;46:75–80.

2 Sharma P, Maffulli N. Tendon injury and tendinopathy: healing and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:187–202.

3 Nakama LH, King KB, Abrahamsson S, et al. Evidence of tendon microtears due to cyclical loading in an in vivo tendinopathy model. J Orthop Res. 2005;2:1199–1205.

4 Rees JD, Wilson AM, Wolman RL. Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology. 2006;45:508–521.

5 Small LN, Ross JJ. Suppurative tenosynovitis and septic bursitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:991–1005.

6 Belzer JP, Durkiu RC. Common disorders of the shoulder. Prim Care. 1996;23:365–388.

7 Neviaser RJ. Lesions of the biceps and tendonitis of the shoulder. Orthop Clin North Am. 1980;11:343–348.

8 Chop WM. Tennis elbow. Postgrad Med J. 1989;36:307–308.

9 Dlabach JA. Nontraumatic soft tissue disorders. Canale ST, ed. Campbell’s operative orthopedics, 10th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003.

10 Safran MR, Fu FH. Uncommon causes of knee pain in the athlete. Orthop Clin North Am. 1995;26:547–559.

11 Khaliq Y, Zhanel GG. Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1404–1410.

12 Alfredson H, Cook J. A treatment algorithm for managing Achilles tendinopathy: new treatment options. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:211–216.

13 Beachley MC, Franklin JW, Ostlund W, et al. Radiology of arthritis. Prim Care. 1993;20:771–794.

14 Grassi W, Filippucci E, Fafina A, et al. Sonographic imaging of tendons. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:969–976.

15 Marsolais D, Cote CH, Frenette J. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug reduces neutrophil and macrophage accumulation but does not improve tendon regeneration. Lab Invest. 2003;83:991–999.

16 Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for the painful shoulder: a meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:224–228.

17 Thacker SB, Gilchrist J, Stroup DF, et al. The impact of stretching on sports injury risk: a systematic review of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:371–378.

18 Foley B, Christopher TA. Injection therapy of bursitis and tendinitis. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JH. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004.