Chapter 34

Teaching Visual: The Importance of the Peripheral Blood Smear

Aarti Shevade MD and Paul Gilman MD

Objectives

Describe the value of preparing and examining a peripheral smear.

Describe the value of preparing and examining a peripheral smear.

List important diagnoses that can be suggested by visual abnormalities of red blood cells (RBCs), WBCs, and platelets on the peripheral smear.

List important diagnoses that can be suggested by visual abnormalities of red blood cells (RBCs), WBCs, and platelets on the peripheral smear.

INTRODUCTION

The peripheral blood smear is the often-neglected foundation of the evaluation of a patient with any cytopenia or blood dyscrasia. One would not think of evaluating a patient with chest pain without looking at the electrocardiogram or a patient with cough and fever without looking at the chest radiograph. With hematologic abnormalities there is too often a reliance on numbers and automated results.

This chapter will familiarize the reader with the blood smear in conditions where it is particularly useful. It will provide an understanding of the normal appearance of the different types of WBCs as well as the normal and important abnormal appearances of RBCs. As demonstrated, the ability to perform a quantitative evaluation of platelets on the peripheral smear is an important skill in evaluating the patient with thrombocytopenia.

While detailed and complex analysis of blood smears is the role of the hematologist, a fundamental knowledge of the use of this diagnostic tool will benefit any clinician.

WHITE BLOOD CELLS AND PERIPHERAL SMEAR

Specific to the evaluation of WBCs, a normal peripheral smear should contain a spectrum of mature leukocytes, including lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils.

Lymphocytes constitute 20% to 25% of the total circulating leukocytes. They are characterized by a clumped acentrically located nucleus and thin rim of blue cytoplasm. Lymphocytes are larger than erythrocytes and are typically 8 to 10 µm in diameter. Atypical lymphocytes are differentiated by a larger cytoplasm. They are often observed in the setting of viral infections (e.g., infectious mononucleosis).

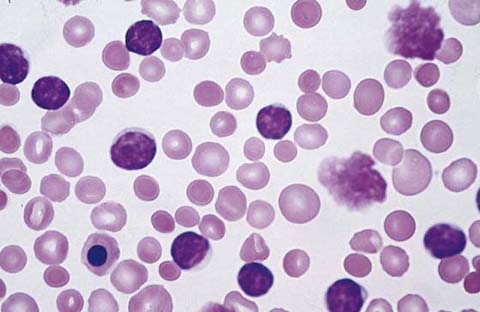

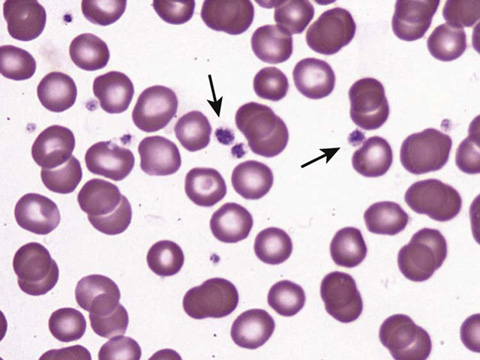

Connect the dots outlining the band form in Figure 34-1.

Figure 34-1 Neutrophil band form. (From McPherson RA, Pincus MR: Henry’s clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2012. Figure 31-17.)

Recognize that this is the immature form of the neutrophil. Its presence in the smear may be a clue to systemic infection, even if the total WBC count is not increased.

Eosinophils constitute less than 5% of all circulating WBCs. They are characterized by orange granules and a bilobed nucleus. Eosinophilia can be seen in allergic states and parasitic infections.

Basophils are the least common of the WBCs. They contain prominent dark-blue to black granules and an S-shaped nucleus. Basophilia can occur in myeloproliferative disorders, hypersensitivity reactions, hypothyroidism, and infection.

Monocytes are the largest of the circulating blood cells and are characterized by a large, acentric, kidney-shaped nucleus that typically has a “moth-eaten” appearance. They remain in circulation for only a few days before migrating into connective tissue, where they differentiate into macrophages.

Myeloblasts are precursors of all three types of granulocytes, the eosinophil, basophil, and neutrophil. They are large cells, contain two to three nucleoli, and do not contain any granules. Their cytoplasm is characterized by blue clumps in a pale-blue background. Acute myeloblastic leukemia results from uncontrolled mitosis of a transformed stem cell whose progeny do not differentiate into the mature cell but stop at the myeloblast stage. Auer rods are seen within the leukemic blast cells of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). These rods are clumps of azurophilic granules that are typically needle-shaped or round and are seen within the cytoplasm. Their presence within a blast cell as noted on a peripheral smear is useful in distinguishing between acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) and AML. They are virtually pathognomonic for AML.

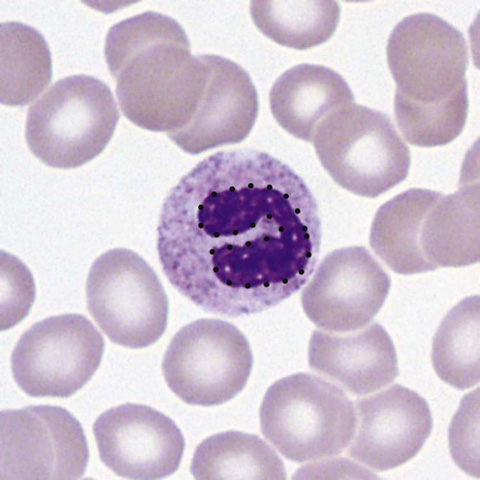

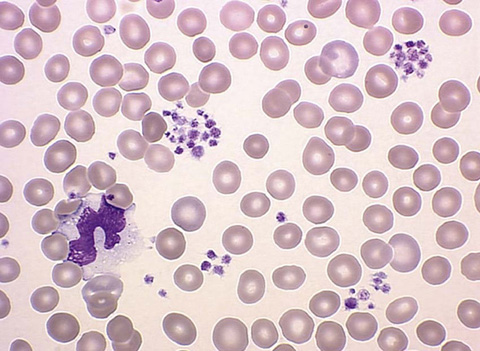

Connect the dots forming one of the Auer rods in Figure 34-2.

Figure 34-2 Auer rods. (From McPherson RA, Pincus MR: Henry’s clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2012. Figure 33-25.)

Recognize that Auer rods are elongated bluish red rods composed of fused lysosomal granules. They can be seen in the cytoplasm of myeloblasts, promyelocytes, and monoblasts and in patients with AML.

THROMBOCYTOPENIA

Thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count less than 150,000/μL. It can occur as a result of reduced bone marrow production, hemodilution, or splenic sequestration.

The peripheral blood smear may show enlarged platelets when platelet turnover is increased.

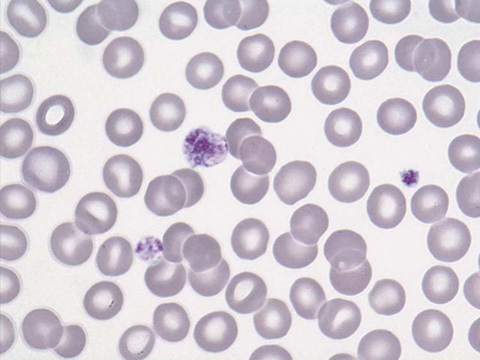

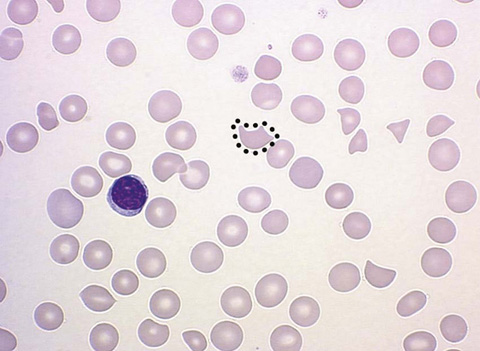

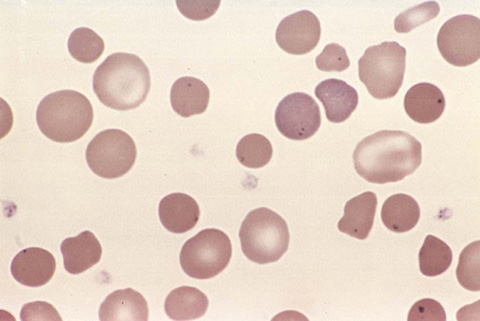

Compare the smear with thrombocytopenia in Figure 34-3 vs. the smear with normal platelets in Figure 34-4.

Figure 34-3 Giant platelets. (From McPherson RA, Pincus MR: Henry’s clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2012. Figure 30-43.)

Figure 34-4 Platelets on a peripheral smear. (From McPherson RA, Pincus MR: Henry’s clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2012. Figure 30-42.)

The presence of immature leukocytes in addition to thrombocytopenia may suggest a bone marrow stem cell disorder such as leukemia. The presence of a nucleated erythrocyte with a low platelet count may indicate an invasive bone marrow process.

Pseudothrombocytopenia, or a falsely low platelet count, is an in vitro phenomenon without clinical relevance. It typically occurs as a result of platelet clumping (Fig. 34-5). If platelet clumping is observed, the platelet count is repeated using a different anticoagulant.

Figure 34-5 Platelet clumping. (From Walsh DT, Caraceni AT, editors. Palliative medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009. Figure 74-12.)

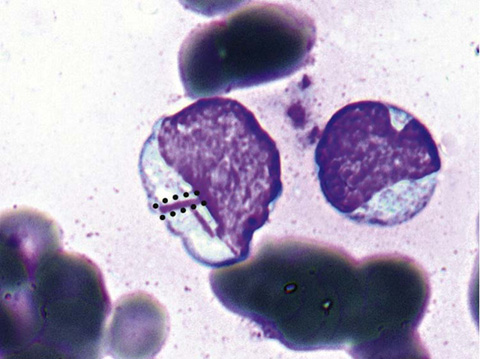

The presence of immature leukocytes in addition to thrombocytopenia may suggest a bone marrow stem cell disorder such as leukemia. The presence of nucleated erythrocytes with a low platelet count may indicate an invasive bone marrow process (Fig. 34-6).

Figure 34-6 Nucleated RBCs. (From Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J, et al. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010. Figure 13-8.)

ACQUIRED HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA: MICROANGIOPATHIC HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia is an acquired hemolytic anemia and is characterized by erythrocyte fragmentation that occurs as a result of mechanical destruction. The characteristic finding on peripheral smear is the schistocyte. The schistocyte is a fragmented part of an RBC that is formed in the setting of a vascular lesion. These vascular lesions can produce shearing forces causing fragmentation of the RBCs. These lesions can also cause inflammation of small-vessel walls, in turn generating fibrin strands that sever the circulating RBCs. The resulting RBC, or schistocyte, is irregularly shaped and asymmetrical, and lacks central pallor.

Connect the dots to circle the schistocyte and identify all other schistocytes in Figure 34-7.

Figure 34-7 Schistocyte. (From Walsh DT, Caraceni AT, editors. Palliative medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009. Figure 74-2.)

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia is seen in eclampsia, preeclampsia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), malignancy, aneurysms, and exposure to certain drugs, most notably cyclosporine and ticlopidine. It can also be seen in patients with mechanical heart valves, especially in the setting of a dysfunctional valve. Treatment of this disorder is specific to the underlying cause.

SPHEROCYTES: AUTOIMMUNE HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA, HEREDITARY SPHEROCYTOSIS

Spherocytes are most commonly found in immunologically mediated hemolytic anemias and in hereditary spherocytosis. Spherocytes are characterized by their spherical shape as opposed to the biconcavity of a normal erythrocyte. They typically have a smaller surface area through which oxygen and carbon dioxide can be exchanged. Spherocyte formation involves several different mechanisms. In immune-mediated spherocytosis, antibodies affix themselves to the RBC, marking them for splenic destruction. Splenic macrophages will partially phagocytize the RBC. The remaining membrane of the RBC will re-form, resulting in a smaller, denser, more spherical RBC, or spherocyte.

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia can present related to certain lymphoproliferative disorders, collagen vascular diseases, drugs or medications, malignancy, and viral infections. Not uncommonly, an underlying cause is never identified. This condition occurs when autoantibodies, most often IgG and IgM, bind to erythrocyte antigens.

Hereditary spherocytosis is a congenital hemolytic anemia caused by an abnormality in the erythrocyte membrane protein (Fig. 34-8). In hereditary spherocytosis, a molecular defect in the gene that encodes the RBC membrane protein leads to its abnormal spherical shape. Specifically, hereditary spherocytosis is characterized by spherocytic erythrocytes with increased osmotic fragility. Osmotic fragility refers to the spherocytes’ tendency to burst when placed into water. Affected patients may have evidence of splenomegaly, gallstones, and leg ulcers. Folate supplementation is an integral component of therapy, and splenectomy may be required to reduce the amount of hemolysis.

Figure 34-8 Spherocyte. (From Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster J, et al. Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010. Figure 14-4.)

Suggested Readings

Bain BJ. Diagnosis from the blood smear. N Engl J Med 2005;353:498–507.

Burns ER, Lou Y, Pathak A. Morphologic diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol 2004;75:18–21.

Eber S, Lux SE. Hereditary spherocytosis—defects in proteins that connect the membrane skeleton to the lipid bilayer. Semin Hematol 2004;41:118–141.

Poyart C, Wajcman H. Hemolytic anemias due to hemoglobinopathies. Mol Aspects Med 1996;17:129–142.

Westerman DA, Evans D, Metz J. Neutrophil hypersegmentation in iron deficiency anaemia: a case-control study. Br J Haematol 1999;107:512–515.