Nausea and Vomiting (Case 20)

Owen Tully MD and Bob Etemad MD

Case: A 65-year-old woman presents with nausea and vomiting. She has a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, mild obesity, and a recent diagnosis of a herniated lumbar disk; her surgical history includes a hysterectomy for fibroid disease. She states the nausea and vomiting has been worsening for 3 days, usually after meals, and is associated with crampy abdominal pain before these episodes. She was recently seen by her primary physician, who added glipizide to her medical regimen because her hemoglobin A1c (HgbA1c) was not well controlled. She has also recently been started on a fentanyl patch for worsening pain in her cervical spine secondary to her herniated disk.

Differential Diagnosis

When a patient presents with symptoms of nausea and vomiting, it is important to consider that some patients may vomit and have minimal nausea, whereas others present with long durations of nausea punctuated with a rare episode of vomiting that does not relieve the nausea. Among the more important factors to consider are the following:

Are the symptoms acute or chronic? Acute nausea or vomiting usually suggests a more urgent issue.

Are the symptoms acute or chronic? Acute nausea or vomiting usually suggests a more urgent issue.

Is there any possibility of pregnancy?

Is there any possibility of pregnancy?

Are there other signs or symptoms that the patient is significantly ill?

Are there other signs or symptoms that the patient is significantly ill?

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• In any woman of childbearing age, be sure to exclude pregnancy.

• Determine the time frame of symptoms. If the symptoms are roughly 1 month or less, an acute cause of the symptoms should be considered, as catastrophic and more dangerous etiologies tend to manifest acutely.

History

• Perform a detailed review of systems to consider the multitude of other etiologies.

Physical Examination

• Abnormal vital signs suggest a more concerning process needing more urgent attention.

• General appearance: Is the patient “miserable” or comfortable? Is there something obvious that strikes you as concerning (distended abdomen, lying in fetal position, abnormally quiet, not moving a particular extremity)? Does the patient appear ill?

• Check for signs of volume depletion by examining the oral mucous membranes, eyes, and skin.

• Lymphadenopathy could suggest either infectious causes or malignancy.

• Signs of muscle atrophy, cachexia, and temporal wasting could suggest malignancy.

• Peripheral neuropathy can be seen in patients with or without diabetic gastroparesis.

Tests for Consideration

|

$11 |

|

|

$12 |

|

|

$9 |

|

|

$4 |

|

|

$19 |

|

|

• Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): Evaluate for gastritis, esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD). |

$600 |

|

$27 |

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

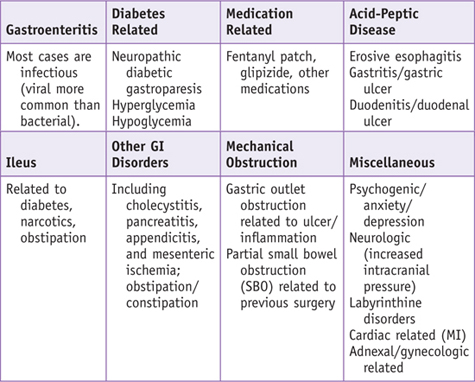

Gastroenteritis |

|

|

Pφ |

Gastroenteritis is inflammation of the lining of the stomach and small and large intestines, most often caused by invasion of the GI tract by infectious agents (viral, bacterial, or parasitic). Viruses including noroviruses, rotavirus, and enteric adenoviruses are the most common etiologies. Fecal-oral spread of these viruses is the most common route of transmission. Infants and young children are particularly at risk, as are people who work in health care settings, day care, and schools. Immunosuppressed patients are at increased risk. |

|

TP |

Patients often present with nausea and vomiting, and/or diarrhea. Signs of volume depletion are commonly noted. Diarrhea is more common with bacterial etiologies, while vomiting is especially common with viral etiologies. Fever and chills are present in 40% to 60% of cases. |

|

Laboratory studies are generally nonspecific. Mild elevations of liver enzymes may be seen in some bacterial and viral infections. Stool leukocytes are more often demonstrated in “invasive” bacterial infections such as that caused by Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, and with certain Escherichia coli strains. Stool testing for rotavirus and other viruses is available, but only used for epidemiologic purposes and not for routine clinical care. |

|

|

Tx |

The treatment is generally supportive. Antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones, should be reserved for patients with a high suspicion of bacterial pathogens, evidence of systemic toxicity, or immunosuppression. Prevention is one of the most important aspects of management, including aggressive hand washing, separating diaper-changing areas from dining areas in day care settings, and vaccination for specific pathogens (i.e., rotavirus). See Cecil Essentials 37. |

|

Small-Bowel Obstruction |

|

|

Pφ |

SBO is due to a physical blockage of the normal flow of intestinal contents in the small bowel. The majority of cases are caused by adhesions from prior surgeries, although cancers, incarcerated hernias, and small-bowel strictures are other causes. |

|

TP |

Patients typically present with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension, and often have abdominal pain that is diffuse and crampy. Absence of flatus is another common presenting symptom. Inspect for scars from previous surgery; listen for bowel sounds, which may be high-pitched, hypoactive, or absent. Tympany to percussion is usually present with distension; if guarding and/or rebound is elicited, consider peritonitis complicating the obstruction. Rectal exam typically reveals an empty rectal vault. |

|

Dx |

Upright abdominal radiographs should be ordered to first evaluate for free air. SBO will classically demonstrate multiple air-fluid levels in the small intestine with distended loops of bowel. CT scan, with water-soluble oral contrast, can be used if plain radiographs are equivocal. A transition point at the obstruction can often be identified. Lack of air or contrast in the distal small intestine or colon is suggestive of a complete obstruction. |

|

Initial management is supportive, with nasogastric (NG) suction, having the patient ingest nothing by mouth (NPO), and IV fluid repletion. If postoperative patients do not show signs of improvement within 12–24 hours, surgical exploration is recommended to evaluate for strangulation. Administration of water-soluble contrast (diatrizoate [Gastrografin]) via NG tube can be diagnostic and, at times, therapeutic. Lysis of adhesions is often indicated, especially in patients with mild distension and proximal obstruction, and who are expected to have a single band of adhesions. See Cecil Essentials 35, 38. |

|

|

Postoperative Ileus |

|

|

Pφ |

Ileus refers to a nonmechanical insult that disrupts the normal peristalsis of the small intestine. It is most common in the postoperative setting, usually up to 5 days. The pathogenesis is multifactorial, including inflammation of the bowel from surgical manipulation, neural inhibitory sympathetic reflexes and local neuroinhibitory peptides acting in response to the surgical insult to the bowel, and narcotic-related delay in bowel transit from systemic opioid use. Other potential etiologies for ileus include metabolic abnormalities, pancreatitis, and other inflammatory states, sepsis, medication reactions, ischemia, and neurologic processes. |

|

TP |

In addition to nausea and vomiting, patients typically present with abdominal distension, bloating, pain, absence of flatus, and/or inability to tolerate oral intake. On physical exam, patients often have abdominal distension and tympany, decreased or absent bowel sounds, and sometimes mild tenderness. The presentation is often very similar to that of an SBO. |

|

Dx |

Abdominal radiographs will show distended loops of bowel with air-fluid levels. CT scan with water-soluble contrast will show these findings as well, yet unlike with SBO, there is no transition point of obstruction. Laboratory studies may demonstrate hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia. |

|

Treatment is largely supportive and very similar to that for SBO. Patients are kept NPO and are repleted with IV fluids; electrolyte imbalances are corrected, and NG tubes are sometimes placed for symptomatic relief. Minimization of narcotics is helpful; ambulation is probably beneficial. No medication has yet been proven to be effective in the treatment of ileus. Postoperative ileus appears to be less profound following laparoscopic surgeries and with the use of epidural instead of general anesthesia. Medications that may be beneficial in the prevention of ileus in the postoperative setting include Cox-2 inhibitors, peripheral-acting µ-opioid receptor antagonists, and magnesium oxide laxatives. See Cecil Essentials 35. |

|

|

Gastroparesis |

|

|

Pφ |

Gastroparesis refers to delayed gastric emptying. Its pathophysiology probably includes disordered motility related to neurologic, hormonal, and smooth muscle factors. By definition, there are no structural abnormalities contributing to the gastric delay. The most common etiology is diabetes mellitus, with autonomic neural injury the proposed mechanism. Other less common causes include medications, infection, acidosis, metabolic disorders, pregnancy, and collagen vascular disorders. In many cases the specific cause is not clearly identified. |

|

TP |

Patients typically present with nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety. Diabetics typically have poorly controlled glucose levels and evidence of end-organ damage including retinopathy and neuropathy. Abdominal exam may show tenderness to palpation, without guarding or rebound. A succussion splash may often be demonstrated. |

|

Dx |

Structural diseases, including gastric outlet obstruction related to malignancy and peptic ulcer disease, should first be excluded with either upper endoscopy or upper GI barium studies. Upper endoscopy will often show retained food debris in the stomach, even after an overnight fast. A thorough review of medications is necessary to rule out possible triggers. Once these steps have been completed, gastric emptying scintigraphy remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Retention of >10% of the ingested meal at 4 hours or >70% at 2 hours is considered diagnostic. Medications that can either delay or increase gastric emptying should be withheld 48 hours prior to scintigraphy. Blood glucose should also be optimized, as hyperglycemia can affect scintigraphy results. |

|

Treatment includes both symptomatic therapy and prokinetic agents. Dietary modifications may help lessen symptoms and include eating small, frequent meals, avoidance of fat, avoidance of fiber to prevent bezoar formation, and avoidance of carbonated beverages, alcohol, and tobacco. Severe cases may require jejunal tube feedings or even total parenteral nutrition (TPN). The use of antinausea medications such as ondansetron is common but without definitive data to support efficacy. Beyond symptom control, promoting motility may be helpful. The use of prokinetic agents, including metoclopramide, domperidone, and erythromycin, is often helpful. Optimization of blood glucose in diabetics is also recommended. The use of botulinum toxin injected into the pylorus has been tried in refractory cases, but results are mixed. Implantation of a gastric neurostimulator has shown benefit for some refractory cases in uncontrolled trials. See Cecil Essentials 37. |

|

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic and therapeutic role of water-soluble contrast agent in adhesive small bowel obstruction

Authors

Branco BC, Barmparas G, Schnuriger B, et al.

Institution

University of Southern California

Reference

Br J Surg 2010;97:470–478

Problem

Diagnosis and therapeutic role of water-soluble contrast with adhesive small-bowel obstruction

Intervention

Administration of water-soluble contrast via NG tube in patients with suspected adhesive SBO

Comparison/control (quality of evidence)

Meta-analysis of 14 prospective studies that aimed to predict the need for surgery in adhesive SBO. Pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and likelihood ratios were derived to predict the need for surgery. For the therapeutic role of water-soluble contrast agents (WSCAs), weighted odds ratio (OR) and weighted mean difference (WMD) were obtained.

Outcome/effect

Fourteen prospective studies were included. The appearance of contrast in the colon within 4 to 24 hours after administration had a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 98% in predicting resolution of SBO. WSCA administration was effective in reducing the need for surgery (OR 0.62; P = 0.007) and shortening hospital stay (WMD –1.87 days; P < 0.001) compared with conventional treatment.

Historical significance/comments

Administration of water-soluble contrast for adhesive SBO has been found to be a viable strategy in diagnosis and therapy.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Be Sensitive to the Barriers Posed by Cultural Differences

As the country grows more ethnically diverse, physicians must remain ever mindful of cultural differences among patient populations. Barriers posed by language and ethnic traditions can result in negative health consequences, including:

Failure to recognize and respond to health problems

Failure to recognize and respond to health problems

Misinterpretation of physician instructions

Misinterpretation of physician instructions

Poor compliance with treatment plans

Poor compliance with treatment plans

Inaccuracies in medical histories

Inaccuracies in medical histories

Studies conducted over an 8-year period indicate that language barriers alone may be responsible for:

Dissatisfaction with health care services

Dissatisfaction with health care services

From Mann BD: Surgery: a competency-based companion. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009, p. 314.

Professionalism

For many etiologies of nausea and vomiting, including SBO and ileus, treatment involves placement of an NG tube. While NG tubes can offer symptomatic relief in terms of gastric decompression, they are quite uncomfortable for the patient and have been described as one of the most unpleasant experiences in the inpatient setting. Discussing uncomfortable procedures with professionalism involves acknowledging the anticipated discomfort while describing the potential benefit in realistic terms.

Systems-Based Practice

Limit Medical Waste and Unnecessary Care

A 77-year-old woman was admitted because of 3 days of nausea and vomiting; she is unable to keep down any liquids or solids. Upon admission, the severity of her state of volume depletion was not appreciated, and because she had a past history of congestive heart failure, her IV rate was written for only 50 mL/hr. After 24 hours she is oliguric and has acute kidney injury; she now requires dialysis at an obvious cost to her quality of life and at a significant financial cost. It is estimated that billions of dollars are wasted every year in the United States on unnecessary care.

Unnecessary care falls into four categories:

Physicians can reduce unnecessary health care costs by identifying sources of wasteful spending, and by making careful and prudent efforts to reduce them.

Suggested Readings

Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:753–763.

Abell TL, Lou J, Tabbaa M, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation for gastroparesis improves nutritional parameters at short, intermediate, and long-term follow-up. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2003;27:277–281.

Abell TL, Van Cutsem E, Abrahaamsson H, et al. Gastric electrical stimulation in intractable symptomatic gastroparesis. Digestion 2002;66:204–212.

Abraham NS, Young JM, Solomon MJ. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes after laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2004;91:1111–1124.

Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;26:1251–1258.

Böhm B, Milsom JW, Fazio VW. Postoperative intestinal motility following conventional and laparoscopic intestinal surgery. Arch Surg 1995;130:415–419.

Forster J, Sarosiek I, Lin Z, et al. Further experience with gastric stimulation to treat drug refractory gastroparesis. Am J Surg 2003;186:690–695.

Hansen CT, Sørensen M, Møller C, et al. Effect of laxatives on gastrointestinal functional recovery in fast-track hysterectomy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;196:311.e1–7.

Kovacs A, Chan L, Hotrakitya C, et al. Rotavirus gastroenteritis. Clinical and laboratory features and use of the Rotazyme test. Am J Dis Child 1987;141:161–166.

Liu SS, Wu CL. Effect of postoperative analgesia on major postoperative complications: a systematic update of the evidence. Anesth Analg 2007;104:689–702.

Rodriguez WJ, Kim HW, Brandt CD, et al. Longitudinal study of rotavirus infection and gastroenteritis in families served by a pediatric medical practice: clinical and epidemiologic observations. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1987;6:170–176.

Sim R, Cheong DM, Wong KS, et al. Prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of pre- and postoperative administration of a COX-2-specific inhibitor as opioid-sparing analgesia in major colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis 2007;9:52–60.

Traut U, Brügger L, Kunz R, et al. Systemic prokinetic pharmacologic treatment for postoperative adynamic ileus following abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;1:CD004930.

Does the patient have a chronic medical condition in which nausea or vomiting may be a manifestation of a life-threatening complication of that condition (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, neurologic disorder, active malignancy)?

Does the patient have a chronic medical condition in which nausea or vomiting may be a manifestation of a life-threatening complication of that condition (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, neurologic disorder, active malignancy)? What is the relationship between the patient’s nausea and his or her vomiting? Timing, duration, exacerbating factors, associated symptoms, and new medications must be considered.

What is the relationship between the patient’s nausea and his or her vomiting? Timing, duration, exacerbating factors, associated symptoms, and new medications must be considered. Inadequate informed consent

Inadequate informed consent Missed appointments

Missed appointments Fewer clinical visits

Fewer clinical visits Lengthier clinical visits

Lengthier clinical visits More laboratory tests

More laboratory tests More ED visits

More ED visits Limited follow-up

Limited follow-up Inefficiencies in the system, such as the lack of electronic medical records leading to tests and imaging studies being needlessly repeated.

Inefficiencies in the system, such as the lack of electronic medical records leading to tests and imaging studies being needlessly repeated. Patient safety problems causing patients to spend additional days in the hospital or be readmitted shortly after discharge.

Patient safety problems causing patients to spend additional days in the hospital or be readmitted shortly after discharge. The risk for malpractice suits leading to the practice of “defensive medicine”—the overuse of diagnostics in an effort to prevent potential litigation.

The risk for malpractice suits leading to the practice of “defensive medicine”—the overuse of diagnostics in an effort to prevent potential litigation. Failure to effectively communicate with patients and their families resulting in futile efforts to prolong a patient’s life.

Failure to effectively communicate with patients and their families resulting in futile efforts to prolong a patient’s life.