CHAPTER 32 Tarsal strip canthoplasty

History

Suspension of the tarsus of the lower eyelid was originally described by Lexer and Eden in 1911.1 Since that time, multiple modifications have been made, most notably by Tenzel,2 Anderson and Gordy,3 Whitaker4 and Ortiz-Monasterio and Rodriguez.5 Alteration in the contour and position of the lower eyelid carries many names. It has been described as the tarsal strip procedure, the lateral canthal sling, lateral canthopexy, lateral canthoplasty, the tarsal tongue, the periosteal strip, horizontal shortening and tarsal suspension.6 While initially described for treatment of functional malposition of the eyelid, current use of the tarsal strip procedure includes many aesthetic adaptations.

Physical evaluation

• Attain a thorough history of ocular and eyelid symptoms, past medical and ocular history (with particular attention to the presence of rosacea, blepharitis, or other cicatricial diseases and thyroid associated orbitopathy) and past surgical history (with attention to any history of prior eyelid or facial cosmetic surgery and trauma).

• Check visual acuity in each eye.

• Examine the contour and position of the lower eyelid – evaluating the distance of the center of the mid-pupillary light reflex to the lower eyelid margin (MRD2) and the presence of inferior scleral show from lower eyelid retraction, ectropion or lower eyelid laxity.

• Determine the cause of lower eyelid malposition by examining for cicatricial changes (cicatricial etiology), facial asymmetry from seventh nerve palsy (paralytic etiology) or, most commonly, excessive laxity (involutional etiology).

• Evaluate lower eyelid laxity with the eyelid snapback test and the eyelid distraction test. The eyelid snapback test is performed by distracting the lower eyelid inferiorly toward the inferior orbital rim. Normal snapback occurs spontaneously. Quantification of abnormal lower lid laxity can be ascertained by counting the number of blinks required for the lid to return to its normal position against the globe. The eyelid distraction test is an estimation of the distance the lower eyelid can be pulled directly off of the globe.

• Ascertain the risk of developing or presence of keratopathy by assessing lagophthalmos during gentle closure and the presence of punctate corneal fluorescein staining (superficial punctate keratopathy).

• Manually elevate and retroplace the lower eyelid at the lateral canthus with a single digit to determine if tarsal shortening and suspension alone will result in adequate lower eyelid shape, contour and position against the globe.

Technical steps

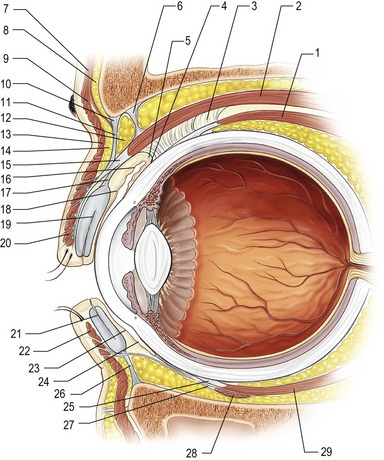

Anatomy

Structurally, the eyelid is divided into anterior, middle and posterior lamellae. The anterior lamella is comprised of skin and orbicularis oculi muscle. The middle lamella contains orbital septum and orbital fat. The posterior lamella of the lower eyelid is made up of tarsus, lower eyelid retractors (capsulopalpebral fascia and inferior tarsal muscle) and conjunctiva. In fashioning a tarsal strip, the anterior and posterior lamellas are split. See Fig. 32.1 for a summary of relevant eyelid and periocular anatomy.

The normal slope of the lower eyelid is slightly upward from medial to lateral, placing the lateral canthus approximately 1–2 mm above the medial canthus. When the lateral canthal angle is lower than the medial canthal angle, this is termed an anti-mongoloid slant. An excessive upward slant of the lateral canthal angle is known as a mongoloid slant. While traumatic lateral canthal dystopia and syndromes can account for these alterations, normal variants are more common. Examination of a patient from the side allows comparison of the anterior aspect of the globe to the lower eyelid and malar eminence. If a negative vector exists, canthal surgery can result in tethering of the eyelid beneath a prominent globe.7 Since both symmetry and stability of facial appearance are important components of any lower lid repositioning procedure, photographs of the patient at a younger age often aid in determining what is “normal” for that individual.

Lateral tarsal strip technical steps

4. Release the orbital septum.

6. Opening of a periosteal slot.

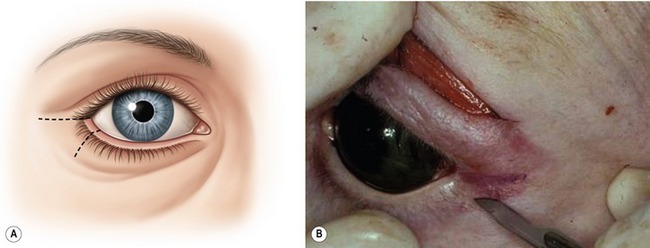

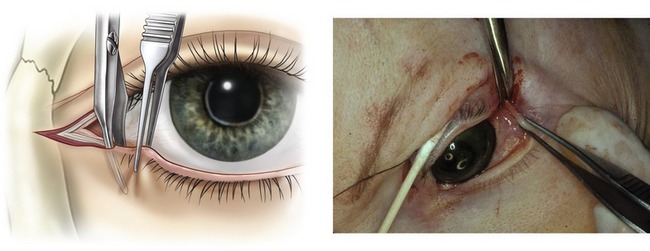

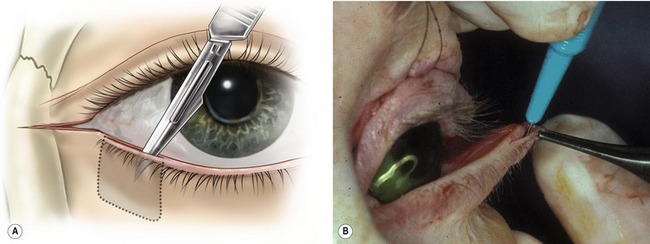

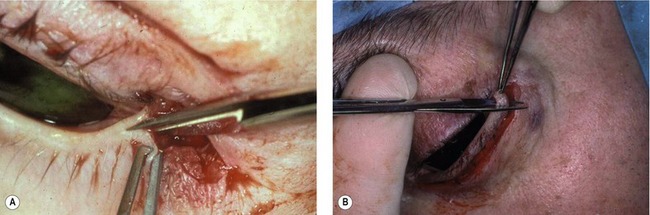

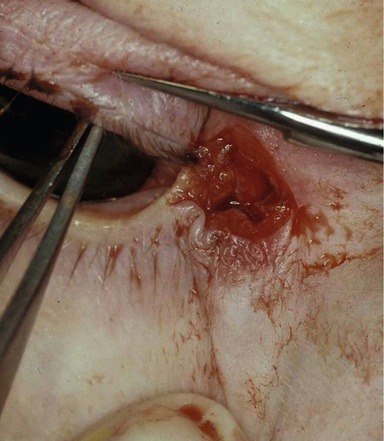

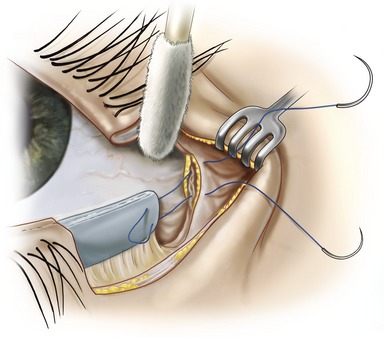

A number 15 blade is used to create a lateral canthal incision in an aesthetically pleasing skin fold of approximately one centimeter (Fig. 32.2A,B). With upward traction on the lateral aspect of the lower eyelid, the inferior crus of the canthal tendon is severed with Stevens scissors (Fig. 32.3A,B). The scissors are directed posteromedially and the orbital septum is released with sharp dissection (Fig. 32.4). If adhesions are present along the septum and/or retractors from prior surgery, these can be bluntly lysed by placing the scissors through the canthal opening and spreading across the middle lamella.

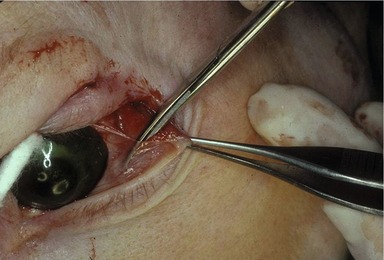

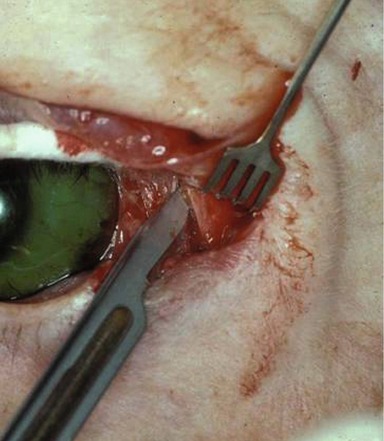

At this point, the lower lid is fully mobile and determination of the appropriate length of strip is ascertained by pulling the lower lid laterally and slightly superiorly towards Whitnall’s tubercle until appropriate height, tension and contour are achieved. Development of the tarsal strip is begun by splitting the anterior and posterior lamella of the lateral lower lid at the grey line with a supersharp blade (Katena instruments #K20-1058, 30°, 3.5 mm) or a number 15 blade (Fig. 32.5A,B). The split is carried for the pre-determined length necessary to give normal lower eyelid tension and contour. Blepharoplasty scissors are used to remove the anterior lamella and cilia from the proposed length of the tarsal strip (Fig. 32.6A,B). Similarly, the mucocutaneous junction is excised. It is not necessary to remove conjunctiva from the strip since it is a non-keratinizing surface. A back-cut through the conjunctiva and lower eyelid retractors is made at the inferior tarsal border for the length of the strip, thus completing formation of the strip (Fig. 32.7).

A periosteal slot is indirectly opened at the inner aspect of the lateral orbital rim with a number 15 blade (Fig. 32.8). The soft tissues are pushed with a swab to indirectly feel the lateral orbital rim. If direct exposure is created by incising down to the rim, significant postoperative edema is produced since two-thirds of the lymphatic for the upper and lower eyelid drain at the lateral orbital tubercle. Any bleeding is controlled with unipolar cautery prior to suturing of the strip to the orbital periosteum.

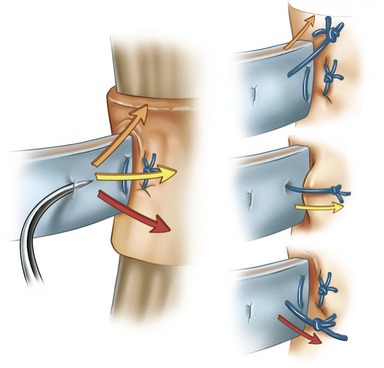

The strip is led beneath the periosteum at the inner aspect of the superolateral orbital periosteum with a double-armed 4-0 Polydek suture on a P-2 needle passed in a mattress fashion (Fig. 32.9). The two arms of the suture are passed in the opening created in periosteum. This opening can be widened with a sharp cautery tip to help obtain both hemostasis and ease of entry. The superior suture is grasped first and using retraction to expose the lateral rim, the suture placed within the two leaves of periosteum within the rim. Lid height and contour is assessed by pulling the upper suture. If necessary, the suture can be backed out and repassed to improve contour or height. Once the upper suture is satisfactory, the lower tarsal suture is passed in a similar fashion through the inner orbital periosteum approximately 2–3 mm inferior to the other suture arm. Adjustments in the vector, height and location within the lateral orbital periosteum of this suture pass give the surgeon options for postoperative contour, lid level, tension and apposition to the globe (Fig. 32.10). The lower limb of the suture can be inferiorly placed to lower the eyelid placement, if needed. This suture must be cut close to the knot. Any exposed Polydek is prone to deeper epithelial inclusion cysts from this braided, non-absorbable suture.

The strip is resupported and the permanent suture is covered with a 4-0 PDS suture passed in an interrupted fashion through the strip and secured to the periosteum (Fig. 32.11). Fine adjustments can be made in lid height and contour with this suture pass. The rim can be “walked” superiorly or inferiorly to gain a second attempt at a good position or symmetry with the contralateral eyelid.

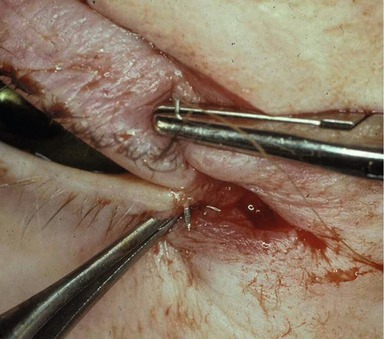

Closure begins by reforming the lateral canthal angle. This is achieved with two interrupted 6-0 chromic sutures. The sutures are passed percutaneously through the upper eyelid, entering just superior to the eyelashes and exiting just posterior to the eyelashes. A mirror image of this pass is performed in the lower eyelid and the sutures secured, concentrating on achieving a symmetric and acute shape to the canthal angle (Fig. 32.12). A single interrupted 6-0 silk suture is passed over the chromic sutures for additional support (Fig. 32.13). The lateral canthal skin incision is closed with interrupted 6-0 silk sutures. The corneal shields are removed. Ophthalmic ointment is applied to the wound and the eye. Patching is not required. Ice compresses are started in the recovery room.

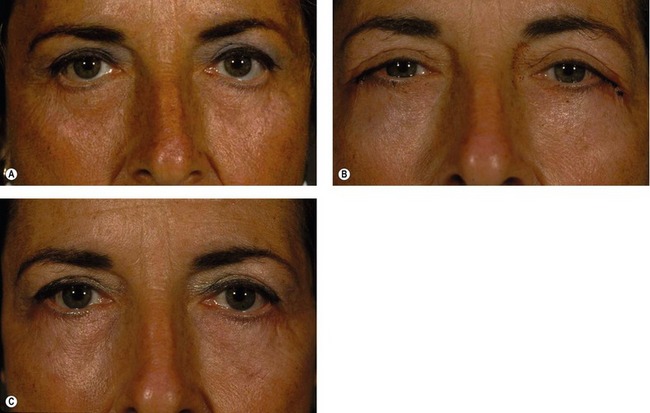

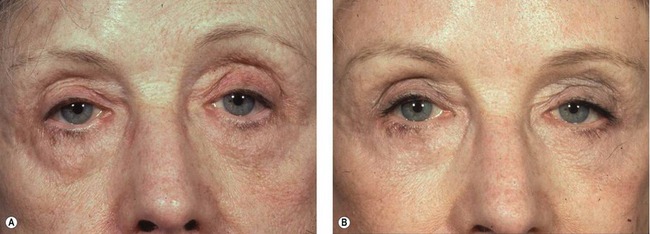

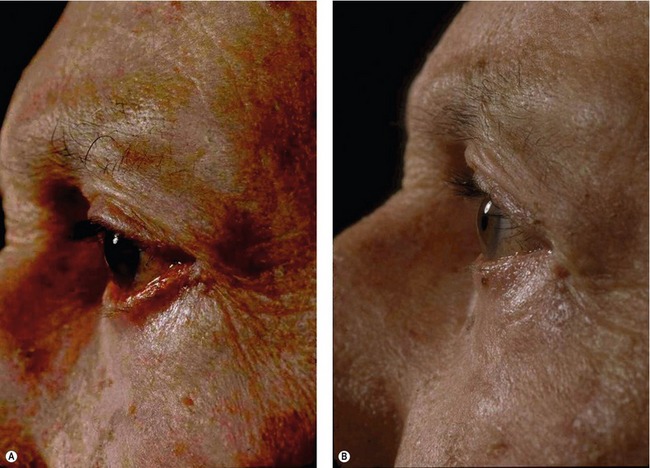

Pre- and postoperative photographs of a typical patient are shown in Fig. 32.14A–C. The tarsal strip procedure can be used for aesthetic enhancement of the lateral canthal angle and palpebral aperture (Fig. 32.15A,B). Additionally, one can cosmetically improve upsweep of the lower eyelid contour without influencing the height of the lower eyelid (Fig. 32.16A,B). Functional improvement of lower eyelid ectropion is shown in Fig. 32.17A,B.

Complications

Bleeding and infection are rare complications of the tarsal strip operation. Care is taken intraoperatively to obtain hemostasis and the well-vascularized eyelid very infrequently succumbs to infection. Careful placement and removal of the protective corneal lens and copious use of ophthalmic lubricating ointment prevents damage to the ocular globe and corneal abrasion. If ocular damage is suspected, prompt evaluation with an ophthalmologist is recommended. Patients may feel discomfort or tenderness at the site of periosteal suture fixation, which usually resolves over weeks to months. Suture exposure or suture granulomas occur infrequently. Suture granulomas can be treated initially with steroid injections; they can be excised later if necessary. Asymmetry may result and can be avoided by careful preoperative examination and intraoperative evaluation of lower eyelid height, contour and tension. The higher eyelid can be stretched and attenuated downward with massage, if needed.

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Differentiating the cause of lower eyelid malposition preoperatively is probably the single most important determinant of a successful outcome. Cases of lower eyelid laxity respond favorably to the lateral tarsal strip procedure, whereas cicatricial causes require recruitment of additional anterior lamella. Cicatricial retraction or ectropion, as can be seen after lower eyelid blepharoplasty, often worsens with a negative vector patient. Further, one must rule out disease states that result in lower eyelid retraction, such as thyroid-related ophthalmopathy (TRO). In TRO, the lower eyelid may retract secondary to infiltration of the periocular tissues with inflammatory cells and activated fibroblasts, or may be the result of proptosis. These changes often require other repair such as posterior lamellar grafting and/or surgical treatment of proptosis.

• Operatively, lysis of the inferior crus of the lateral canthal tendon is best performed indirectly by feel. Traction is placed on the lateral lower eyelid away from the globe and the scissors are used to “strum” the firm tendonous insertions to the orbital periosteum. With each cut, the surgeon should feel a release of the lower lid, and subsequently, be able to pull the lower eyelid further from the globe. Two or three cuts are usually sufficient to fully release the lower lid. Additional dissection may be necessary to release orbicularis adhesions from prior surgery.

• Improved cosmesis can be obtained by two simple tips. First, following attachment of the strip to the periosteum and retroplacement of the globe, herniation of lateral fat or telescoping of orbicularis muscle may occur. If apparent, this should be addressed by excision. Second, closure of the lateral canthal incision should start laterally and work medially, to milk any excess tissue towards the canthus. Scarring and/or excess tissue can be better hidden in the lateral canthus and will improve cosmesis.

• The patient should look slightly overcorrected at the end of the procedure and in the early postoperative period. With time, the lower eyelid height moves inferiorly and the contour softens (see Fig. 32.14A–C).

• Midface lifting often increases and bunches the tissue of the lower eyelid and responds favorably to concurrent lateral tarsal suspension.

Pitfalls

• Multiple attempts at the tarsal suture pass will result in diminished integrity of the connective tissue and “cheese-wiring” of the suture will occur more frequently. Try to get the tarsal suture pass correct on the first or second attempt.

• Fixation of the strip to the periosteum should be confirmed by pulling on the suture after the periosteal pass. If periosteum has been secured, the suture will not “give” with firm traction away from the orbital rim. If the suture is not fixed to the periosteum, it should be backed out and repassed.

• Failure to bury the periosteal suture with the second support suture of 4-0 PDS increases the risk for granuloma formation and exposure of the permanent suture.

• Placement of the periosteal suture at the orbital rim is too anterior and often results in poor globe apposition to the lower eyelid. Palpate Whitnall’s tubercle on a skull and you will realize that the correct attachment of the lateral canthal tendon is deep to the rim by approximately 5 mm.

• Meticulous closure of the lateral canthal angle is necessary for two reasons. First, reformation of the acute shape to the canthus avoids alteration of the patient’s appearance and creates an almond-shaped eyelid with a slight lateral upsweep in a previously rounded canthus. Second, override of the upper eyelid can cause ocular irritation and inflammation. Occasionally the lateral upper eyelid overrides the lower from edema. This should be left to resolve on its own, avoiding the temptation to shorten the upper eyelid when it does override intraoperatively.

1. Eden R. Uber die chirurgishe Behandlung der peripheren Facialislahmung. Beitr Klin Chir. 1911;73:116.

2. Tenzel RR. Treatment of lagophthalmos of the lower lid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;81:366.

3. Anderson RL, Gordy DD. The tarsal strip procedure. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:2192.

4. Whitaker LA. Selective alteration of palpebral fissure form by lateral canthopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74(5):611.

5. Ortiz-Monasterio F, Rodriguez A. Lateral canthoplasty to change the eye slant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(1):1.

6. Lisman RD, Rees T, Baker D, Smith B. Experience with tarsal suspension as a factor in lower lid blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;94(6):671–681.

7. Glatt PM, Jelks GW, Jelks EB, Wood M, Gadangi P, Longaker MT. Evolution of the lateral canthoplasty: techniques and indications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(6):1396.