Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Compare the different forms of lupus, citing manifestations, incidence, and other features.

• Name the two most common drugs that can cause drug-induced lupus.

• Explain the epidemiology and signs and symptoms of SLE.

• Describe the immunologic manifestations of SLE, including diagnostic evaluation.

• Discuss the laboratory evaluation of antinuclear antibodies.

• Analyze selected SLE case studies. Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the principle, sources of error, limitation, and clinical application of the antinuclear antibody visible method

• Describe the principle and clinical applications of the rapid slide test for antinucleoprotein and autoimmune enzyme immunoassay ANA screening test

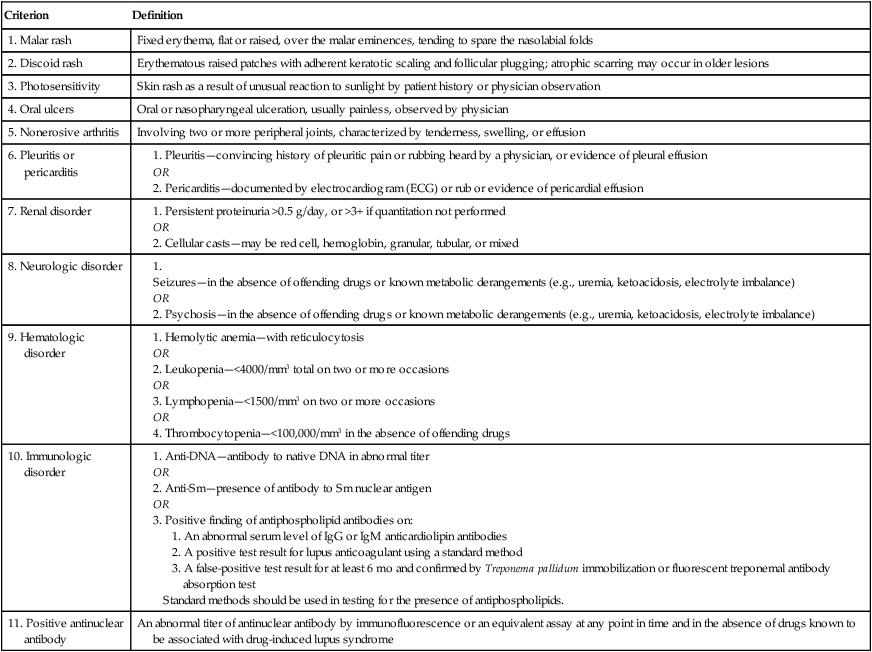

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the classic model of an autoimmune disease. SLE is a systemic rheumatic disorder and the term used most often for the group of disorders that includes SLE and other abnormalities involving multiple systems (e.g., joints, connective tissue, collagen vascular system) in the disease process. Table 29-1 lists the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of SLE.

Table 29-1

| Criterion | Definition |

| 1. Malar rash | Fixed erythema, flat or raised, over the malar eminences, tending to spare the nasolabial folds |

| 2. Discoid rash | Erythematous raised patches with adherent keratotic scaling and follicular plugging; atrophic scarring may occur in older lesions |

| 3. Photosensitivity | Skin rash as a result of unusual reaction to sunlight by patient history or physician observation |

| 4. Oral ulcers | Oral or nasopharyngeal ulceration, usually painless, observed by physician |

| 5. Nonerosive arthritis | Involving two or more peripheral joints, characterized by tenderness, swelling, or effusion |

| 6. Pleuritis or pericarditis | |

| 7. Renal disorder | |

| 8. Neurologic disorder | |

| 9. Hematologic disorder | |

| 10. Immunologic disorder |

1. Anti-DNA—antibody to native DNA in abnormal titer 2. Anti-Sm—presence of antibody to Sm nuclear antigen 3. Positive finding of antiphospholipid antibodies on: 1. An abnormal serum level of IgG or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies 2. A positive test result for lupus anticoagulant using a standard method 3. A false-positive test result for at least 6 mo and confirmed by Treponema pallidum immobilization or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test Standard methods should be used in testing for the presence of antiphospholipids. |

| 11. Positive antinuclear antibody | An abnormal titer of antinuclear antibody by immunofluorescence or an equivalent assay at any point in time and in the absence of drugs known to be associated with drug-induced lupus syndrome |

From Hochberg MC: Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus (letter), Arthritis Rheum 40:1725, 1997 and The American College of Rheumatology www.rheumatology.org 2012.

Different Forms of Lupus

There are several forms of lupus, including discoid, systemic, drug-induced, and neonatal lupus.

Drug-induced lupus occurs after the use of certain prescribed drugs (Box 29-1). The most frequently used drugs associated with drug-induced lupus are hydralazine hydrochloride and procainamide hydrochloride. Factors such as the rate of drug metabolism, the drug’s influence on immune regulation, and the host’s genetic composition are all believed to influence pathogenesis. Some drugs (e.g., oral contraceptives, isoniazid) induce serum antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) without symptoms. High antibody titers may exist for months without the development of clinical symptoms.

Signs and Symptoms

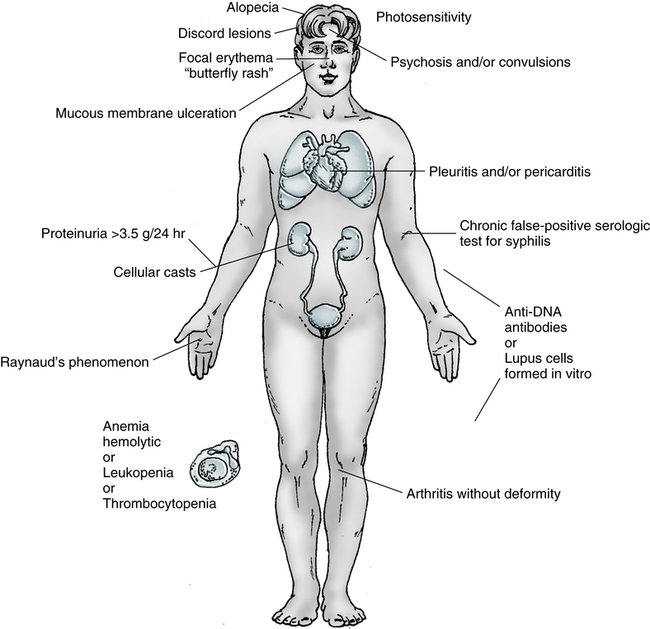

Manifestations of the disease range from a typical mild illness limited to a photosensitive facial rash and transient diffuse arthritis to life-threatening involvement of the CNS or renal, cardiac, or respiratory system (Fig. 29-1). In the early phases, it is often difficult to distinguish SLE from other systemic rheumatic disorders, such as progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), polymyositis, primary Sjögren’s syndrome, primary Raynaud’s phenomenon, and rheumatoid arthritis. Polyarthritis and dermatitis are the most common clinical manifestations.

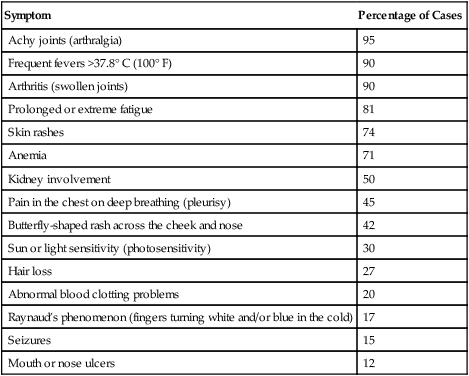

The course of the disease is highly variable. It usually follows a chronic and irregular course, with periods of exacerbations and remissions. Clinical signs and symptoms can include fever, weight loss, malaise, arthralgia (joint pain) and arthritis (inflammation of the joints), and the characteristic erythematous, maculopapular (“butterfly”) rash over the bridge of the nose (Table 29-2). In addition, there is a tendency toward increased susceptibility to common and opportunistic infections. Multiple organ systems may be affected simultaneously.

Table 29-2

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Symptoms

| Symptom | Percentage of Cases |

| Achy joints (arthralgia) | 95 |

| Frequent fevers >37.8° C (100° F) | 90 |

| Arthritis (swollen joints) | 90 |

| Prolonged or extreme fatigue | 81 |

| Skin rashes | 74 |

| Anemia | 71 |

| Kidney involvement | 50 |

| Pain in the chest on deep breathing (pleurisy) | 45 |

| Butterfly-shaped rash across the cheek and nose | 42 |

| Sun or light sensitivity (photosensitivity) | 30 |

| Hair loss | 27 |

| Abnormal blood clotting problems | 20 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon (fingers turning white and/or blue in the cold) | 17 |

| Seizures | 15 |

| Mouth or nose ulcers | 12 |

Adapted from Lupus Foundation of America: General Lupus Fact Sheet, 2012 (http://www.lupus.org/webmodules/webarticlesnet/?z=8&a=351org).

Cutaneous Features

Approximately 20% to 25% of patients with SLE develop dermal disorders as the initial manifestation of the disease. As many as 65% of patients will develop a cutaneous abnormality during the course of the disease. The characteristic erythematous, maculopapular butterfly rash across the nose and upper cheeks is the cutaneous feature for which the disease is named—lupus erythematosus, the “red wolf” (Fig. 29-2). This rash may also be observed on the arms and trunk. Exposure to UV light will worsen erythematous, as well as other types of, cutaneous lesions.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Serologic Findings

• Antibody to double-stranded DNA

• Levels of C3 and C4 (with C4 probably being the most sensitive result)

Antibodies

Antinuclear Antibodies

Characteristics and Implications

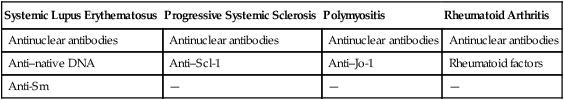

ANAs are a heterogeneous group of circulating immunoglobulins that include IgM, IgG, and IgA. These immunoglobulins react with the whole nucleus or nuclear components (e.g., proteins, DNA, histones) in host tissues; therefore, they are true autoantibodies. Generally, ANAs have no organ or species specificity and are capable of cross-reacting with nuclear material from human beings (e.g., human leukocytes) or various animal tissues (e.g., rat liver, mouse kidney). ANAs are found in other diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), are associated with certain drugs, and are found in older adults without disease (Table 29-3). Thus, assays for ANAs are not specific for SLE. ANAs are present in more than 95% of SLE patients. Because the detection of ANAs is not diagnostic of only SLE, their presence cannot confirm the disease, but the absence of ANAs can be used to help rule out SLE. The significance of the presence of ANAs in a patient’s serum must be considered in relation to the patient’s age, gender, clinical signs and symptoms, and other laboratory findings.

Table 29-3

Antibodies in Systemic Rheumatic Diseases

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | Progressive Systemic Sclerosis | Polymyositis | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Antinuclear antibodies | Antinuclear antibodies | Antinuclear antibodies |

| Anti–native DNA | Anti–Scl-1 | Anti–Jo-1 | Rheumatoid factors |

| Anti-Sm | — | — | — |

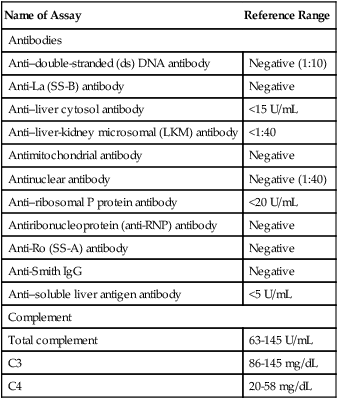

Systematic Classification

Patients with SLE are characterized by the presence of antibodies to multiple antigens, including Sm, RNP, dsDNA, chromatin, and SS-A/Ro (Table 29-4). There are 11 criteria for the diagnosis of SLE and, for a definitive diagnosis, patients must meet at least four of these criteria (see Table 29-1). Two of the criteria are a positive ANA and the detection of antibodies to Sm, dsDNA, or cardiolipin. Antibodies to Sm are detected in 20% to 30% of SLE patients and antibodies to dsDNA may occur in up to 60% of patients. Antibodies to Sm and RNP typically occur together because they react with different proteins that are associated in an RNP particle called a spliceosome. A positive Sm indicates a high probability of SLE.

Table 29-4

Immunologic Assays for Detection and Monitoring of SLE

| Name of Assay | Reference Range |

| Antibodies | |

| Anti–double-stranded (ds) DNA antibody | Negative (1:10) |

| Anti-La (SS-B) antibody | Negative |

| Anti–liver cytosol antibody | <15 U/mL |

| Anti–liver-kidney microsomal (LKM) antibody | <1:40 |

| Antimitochondrial antibody | Negative |

| Antinuclear antibody | Negative (1:40) |

| Anti–ribosomal P protein antibody | <20 U/mL |

| Antiribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP) antibody | Negative |

| Anti-Ro (SS-A) antibody | Negative |

| Anti-Smith IgG | Negative |

| Anti–soluble liver antigen antibody | <5 U/mL |

| Complement | |

| Total complement | 63-145 U/mL |

| C3 | 86-145 mg/dL |

| C4 | 20-58 mg/dL |

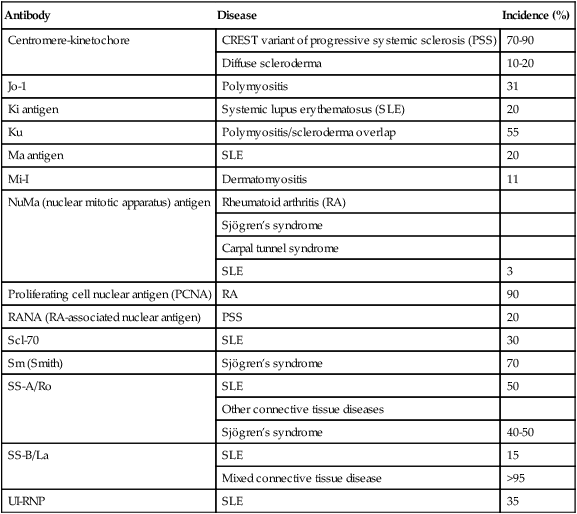

Antibodies to Nonhistone Proteins

Another primary class of ANAs in systemic autoimmune disorders is characterized by reactivity with soluble nonhistone nuclear protein and RNA-protein complexes. Clinically important antibodies that react with nuclear nonhistone proteins are listed in Table 29-5.

Table 29-5

Antibodies to Nonhistone Proteins (NhPs) and NhP-RNA Complexes in Systemic Rheumatic Diseases

| Antibody | Disease | Incidence (%) |

| Centromere-kinetochore | CREST variant of progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS) | 70-90 |

| Diffuse scleroderma | 10-20 | |

| Jo-1 | Polymyositis | 31 |

| Ki antigen | Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | 20 |

| Ku | Polymyositis/scleroderma overlap | 55 |

| Ma antigen | SLE | 20 |

| Mi-I | Dermatomyositis | 11 |

| NuMa (nuclear mitotic apparatus) antigen | Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | ||

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | ||

| SLE | 3 | |

| Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) | RA | 90 |

| RANA (RA-associated nuclear antigen) | PSS | 20 |

| Scl-70 | SLE | 30 |

| Sm (Smith) | Sjögren’s syndrome | 70 |

| SS-A/Ro | SLE | 50 |

| Other connective tissue diseases | ||

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 40-50 | |

| SS-B/La | SLE | 15 |

| Mixed connective tissue disease | >95 | |

| UI-RNP | SLE | 35 |

CREST, Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia.

Adapted from Reimer G, Tan E: Antinuclear antibodies. In Stein J, editor: Internal medicine, Boston, 1987, Little, Brown.

Laboratory Evaluation

Indirect Immunofluorescent Tests for Antinuclear Antibody

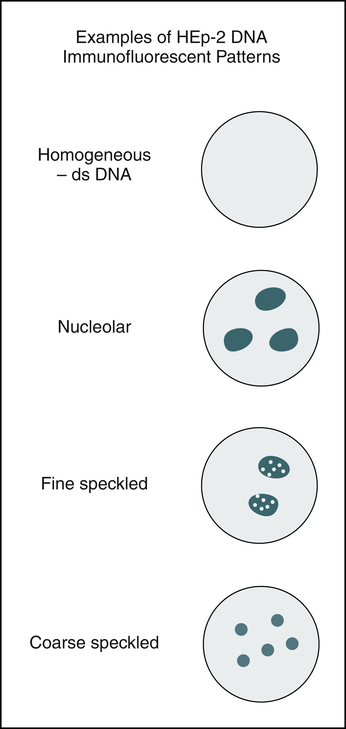

Several different patterns of fluorescence reactivity are seen (see Color Plates #13-#16 and Figure 29-3), depending on whether the ANAs have reacted with the whole nucleus or with nuclear components, such as the nuclear proteins, DNA, or histone (a simple protein). This difference in nuclear fluorescence pattern reflects specificity for various diseases. Patterns are described as being diffused or homogeneous, peripheral, speckled, or nucleolar fluorescence. Nuclear rim (peripheral) patterns correlate with antibody to native DNA and DNP and bear a correlation with SLE, SLE activity, and lupus nephritis. Homogeneous (diffused) patterns suggest SLE or another connective tissue disorder. Speckled patterns are found in many diseases, including SLE. Nucleolar patterns are seen in patients with PSS and Sjögren’s syndrome.

Indirect Immunofluorescent Technique

Interpretation of Staining Patterns of Major Rheumatic Autoantibodies

Because ANAs react with the whole nucleus or with nuclear components (e.g., proteins, DNA, histone), reaction patterns reflect the distribution of the various antigens in the nuclei. Major ANAs are detected on all Hep-2 slides, but detection of antibodies to SS-A/Ro varies according to the fixation method. Alcohol diminishes or destroys the SS-A/Ro speckled ANA pattern, leading to a negative ANA. It is always important to include a control for antibodies to SS-A/Ro. Several patterns of reactivity can be observed when a slide is examined in the ANA procedure (Table 29-6).

Table 29-6

Antinuclear Antibody Patterns and Disorders

| ANA Staining Pattern | Antibody Specificities | Related Disorders |

| Homogeneous | nDNA dsDNA ssDNA DNP Histones |

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Sjögren’s syndrome Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) |

| Peripheral or rim | nDNA dsDNA DNP |

Active SLE Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Speckled | Smith (Sm) RNP |

SLE RA Sjögren’s syndrome Progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS) MCTD |

| Nucleolar | 4-6S RNP | Scleroderma Sjögren’s syndrome Undiagnosed illnesses manifesting Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Discrete, speckled | Centromere DNA, RNA, ENA |

CREST variant of PSS |

CREST, Calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia.

Treatment

• Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are prescribed for a variety of rheumatic diseases, including lupus. Examples include acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), ibuprofen (Motrin), and naproxen (Naprosyn). These drugs are usually recommended for muscle and joint pain and arthritis. Newer NSAIDs contain a prostaglandin in the same capsule (Arthrotec). The other NSAIDs work in the same way as aspirin, but may be more potent.

• Acetaminophen. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is a mild analgesic that can often be used for pain. It has the advantage of causing less stomach irritation than aspirin but is not nearly as effective at suppressing inflammation as aspirin.

• Steroids (e.g., prednisone) are used to reduce inflammation and suppress activity of the immune system. Side effects occur more frequently when steroids are taken over long periods at high doses. These side effects include weight gain, a round face, acne, easy bruising, thinning of the bones (osteoporosis), high blood pressure, cataracts, onset of diabetes, increased risk of infection, stomach ulcers, hyperactivity, and increased appetite.

• Antimalarials. Chloroquine (Aralen) or hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), typically used to treat malaria, may also be useful for some individuals with lupus. Antimalarials are most often prescribed for the skin and joint symptoms of lupus.

• Immunomodulating drugs. Azathioprine (Imuran) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), cytotoxic drugs, act in a manner similar to that of corticosteroids in that they suppress inflammation and tend to suppress the immune system.

• Anticoagulants. Anticoagulants range from aspirin at a very low dose to heparin or coumadin. Generally, such therapy is lifelong in those with lupus and follows an episode of embolus or thrombosis.

Antinuclear Antibody Visible Method

Antinuclear Antibody Visible Method

Principle

Reporting Results

• Negative: No cytoplasmic or nuclear-specific stain is observed. The cells may be slightly colored because of some nonspecific reaction of the peroxidase stain reagent.

• Positive: Serum is considered positive if the nuclei of the cells stain more intensely than the negative control well and there is a clearly discernible pattern of colorations.

A grading scale similar to the one shown in Box 29-2 may be helpful in establishing the criteria for each laboratory. Positive specimens should be confirmed by repeating the test with twofold dilutions of serum. All positive ANA patterns should be titered to end point dilution to detect possible mixed antinuclear reactions that may not be apparent when interpreting a single screening dilution. The end point titer is the last serial dilution in which 1+ coloration with a clearly discernible pattern is detected.

Clinical Applications

The significance of a positive ANA depends on the titer and to a lesser extent on the observed pattern (see Table 29-6). There is no general agreement on the significance of the various patterns and it should be noted that some patterns may mask other patterns in high concentration. Interpretation of ANA patterns can provide additional information about the type of nuclear component reacting.

Chapter Highlights

• Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is the classic model of autoimmune disease.

• No single cause of SLE has been identified, but a primary defect in immune system regulation is considered important in its pathogenesis. Other influences include the effect of estrogens, genetic predisposition, and extraneous factors.

• SLE is a disease of acute and chronic inflammation. Lymphocyte subset abnormalities are a major immunologic feature of SLE. The regulation of antibody production of B lymphocytes, ordinarily a function of the subpopulation of T suppressor cells, appears defective in SLE.

• Circulating immune complexes are the hallmark of SLE. Patients exhibit multiple serum antibodies that react with native or altered self antigens. Demonstrable antibodies include antibodies to nuclear components, cell surface and cytoplasmic antigens of polymorphonuclear and lymphocytic leukocytes, erythrocytes, platelets, and neuronal cells, and IgG.

• Antibodies also combine with their corresponding antigens to form immune complexes. When the mononuclear phagocyte system is unable to eliminate them entirely, these immune complexes accumulate in the blood circulation. These circulating immune complexes are deposited in the subendothelial layers of the vascular basement membranes of multiple target organs, where they mediate inflammation.

• The antinuclear antibody (ANA) procedure is a valuable screening tool for SLE. Demonstration of ANAs can indicate various systemic autoimmune connective tissue disorders characterized by antibodies that react with different nuclear components, such as double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, and Sm antigen. ANAs can be found in SLE, MCTD, PSS (or scleroderma), Sjögren’s syndrome, polymyositis-dermatomyositis, and RA. A small percentage of patients with neoplastic diseases may also demonstrate the presence of ANAs.

• ANAs are classified into antibodies to DNA, antibodies to histones, antibodies to nonhistone proteins, and antibodies to nuclear antigens. Antibodies to DNA can be divided into two major groups:

• Antibodies that react with native (double-stranded) DNA

• Antibodies that recognize denatured (single-stranded) DNA only

• Detection of autoantibodies by immunofluorescence is extremely sensitive and may show positive results when ANA procedures (e.g., complement fixation or precipitation) yield negative results. At present, immunofluorescence is the most widely used technique for ANA screening.