Hepatic system

A Cirrhosis and portal hypertension

Pathophysiology

Chronic alcoholism is the most common cause of cirrhosis (Laënnec’s cirrhosis) in the United States. Cirrhosis is also caused by biliary obstruction, chronic hepatitis, right-sided heart failure, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis. Anatomic alterations secondary to hepatocyte necrosis are the primary cause of the deterioration that occurs in liver function.

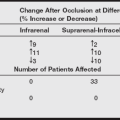

Over time, the liver parenchyma is replaced by fibrous and nodular tissue, which distorts, compresses, and obstructs normal portal venous blood flow. Portal hypertension develops and impairs the ability of the liver to perform various metabolic and synthetic processes. Obstructive engorgement of vessels within the portal system ultimately results in transmission of increasing backpressure within the splanchnic circulation. Therefore, splenomegaly, esophageal varices, and right-sided heart failure ensue in addition to deterioration in liver function.

The development of esophageal varices places the patient at risk for spontaneous, severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Fluid sequestration resulting from ascites causes consequent alteration in intravascular fluid dynamics and alteration in the renin–angiotensin system. Subsequent reduction in renal perfusion results in eventual renal failure in conjunction with hepatic failure (hepatorenal syndrome). Failure of the liver to clear nitrogenous compounds (ammonia) from the blood contributes to the development of progressive mental status changes (caused by encephalopathy), ultimately leading to coma.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of cirrhosis may not be strongly correlated with the severity of the disease process. Patients may have severe liver disease without overt jaundice and ascites. However, the eventual development of jaundice and ascites is observed in most patients as the disease process progresses. Other signs of severe liver disease include gynecomastia, spider angiomata, palmar erythema, and asterixis. Hepatic fibrosis results from the presence of other diseases; portal hypertension ensues, along with its sequelae. These diseases include Budd-Chiari syndrome (vena cava or hepatovenous obstruction), idiopathic portal fibrosis (Banti syndrome), schistosomiasis, and certain rare congenital fibrotic disorders. Venous occlusive disease secondary to metastases, primary hepatic neoplasia, or thromboembolism is also associated with portal hypertension.

Diagnostic and laboratory results

Laboratory changes in the presence of portal hypertension include a hematocrit of 30% to 35%; hyponatremia resulting from increased secretion of antidiuretic hormone; blood urea nitrogen greater than 20 mg/dL; and elevated plasma bilirubin, transaminases, and alkaline phosphatase concentrations.

Treatment

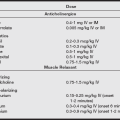

Treatment is supportive until liver transplantation can be undertaken. Variceal bleeding involves replacement of blood loss, vasopressin infusion (0.1–0.9 units/min intravenously), balloon tamponade (Sengstaken-Blakemore tube), endoscopic sclerosis, or the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt–stent procedure to stop the bleeding. If bleeding does not stop or recurs, emergency surgical procedures such as shunts (portocaval or splenorenal), esophageal transection, or gastric devascularization may be needed. Coagulopathies should be corrected by replacing clotting factors with fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) or cryoprecipitate. Platelet transfusions should be performed preoperatively for counts less than 100,000 mm3. Preservation of renal function involves avoiding aggressive diuresis while correcting acute intravascular fluid deficits with colloid infusions.

Anesthetic considerations

The dosage of muscle relaxants should be reduced, depending on hepatic elimination (e.g., pancuronium, vecuronium) because of reduced plasma clearance. Cisatracurium may be the relaxant of choice. The duration of action of succinylcholine may be prolonged as a result of reduced levels of pseudocholinesterase. Half-lives of opioids may be prolonged, leading to prolonged respiratory depression. Regional anesthesia may be used in patients without thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy if hypotension is avoided (perfusion to the liver becomes highly dependent on hepatic arterial blood flow). After removal of large amounts of ascitic fluid, colloid fluid replacement may be necessary to prevent hypotension. Whole blood may be preferable to packed red blood cells when replacing blood loss. Coagulation factors and platelet deficiencies should be corrected with FFP and platelet transfusions, respectively. Citrate toxicity can occur in these patients because of impaired metabolism of the citrate anticoagulant in blood products. Intravenous calcium should be given to reverse the negative inotropic effects of a reduction in serum ionized calcium levels. For patients with esophageal varices, placement of a nasogastric tube or esophageal can cause rupture and uncontrolled bleeding.

Therapeutic modalities for portal hypertension

Pharmacologic management of patients with portal hypertension and acute variceal bleeding is considered secondary to endoscopic treatment and traditionally consists of intravenous infusion of vasopressin or somatostatin. Vasopressin is a splanchnic vasoconstrictor but may also induce undesirable systemic vasoconstriction. Infusion of vasopressin is initiated at 0.1 to 0.4 U/min. Concurrent infusion of nitroglycerin, titrated at 40 mcg/min, may be used to attenuate coronary arterial vasoconstriction and to control systolic blood pressure at 100 to 110 mmHg. In the presence of profound variceal exsanguination and hemodynamic instability, vasopressin may be used in conjunction with mechanical compression of bleeding esophageal varices provided by insertion of a triple-lumen Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Use of this device also requires endotracheal intubation for airway support and for prevention of pulmonary aspiration.

Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, has been shown to be equally as effective as vasopressin in pharmacologic control of variceal bleeding. Infused at 50 mcg/hr, octreotide acts as a potent and reversible inhibitor of gastrointestinal peptide hormone activity, thereby decreasing gut motility and venous return to the portal circulation. Octreotide has also been shown to be equally as efficacious as sclerotherapy in acute treatment of variceal hemorrhage. Endoscopic sclerotherapy, usually performed with the patient under intravenous titrated sedation, has been recognized as the treatment of choice in definitive correction of variceal bleeding. Sclerotherapy is accomplished endoscopically by injection of a thrombosing agent either directly into the bleeding variceal or through creation of a fibrotic overlayer over the varix, accomplished by injection of the sclerosing agent proximal to the paravariceal mucosa. A course of treatments is usually necessary to reduce the incidence of rebleeding. Rebleeding, however, continues to be problematic in this subset of patients, with an incidence of up to 60%.

B Hepatic failure

Definition

Hepatic failure occurs when massive necrosis of liver cells results in the development of a life-threatening loss of functional capacity that exceeds 80% to 90%. Hepatic failure can result from acute or chronic liver disease.

Incidence

The major causes of hepatic failure in the United States are related to the effects of viral hepatitis or drug-related liver injury. Each year, an estimated 2000 cases of hepatic failure in the United States are related to viral hepatitis. This accounts for 1% of all deaths and 6% of all liver-related deaths.

Diagnostic and laboratory findings

Most proteins associated with the promotion or inhibition of coagulation are synthesized in the liver. When one is reviewing laboratory data, special attention should be given to coagulation studies, liver function studies, complete blood count, electrolytes, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) should be performed to rule out any possible cardiac arrhythmias related to acidemia, electrolyte abnormalities, or hypoxemia associated with hepatic failure. The patient with liver failure is at risk for the development of acid–base derangements. Respiratory alkalosis may result from hyperventilation related to an abnormality of central regulation. Respiratory acidosis may be caused by endotoxins, increased intracranial pressure, or pulmonary sequelae, which depress respiratory centers. Metabolic acidosis is also possible, related to substantial tissue damage and decreased clearance of lactic acid by the failing liver.

The hypoxemia associated with liver failure can be attributed to aspiration, atelectasis, infection, hypoventilation, or their combinations. Results of chest radiography should be obtained to rule out evidence of pulmonary edema or adult respiratory distress syndrome. Listed in the following table is a guide to laboratory results in liver failure.

Laboratory Results in Liver Failure

| Laboratory Study | Normal | Liver Failure |

| White blood cell count | 3.5–10.6 cells/mm3 | Decreased |

| Hemoglobin | 11.5–15.1 g/dL | Decreased |

| Hematocrit | 34.4%–44.2% | Decreased |

| Platelet count | 150–450/mm3 | Decreased |

| Prothrombin time | 11–14 sec | Increased |

| Partial thromboplastin time | 20–37 sec | Increased |

| Bilirubin | Plasma: 0.3–1.1 mg/dL Indirect: 0.2–0.7 mg/dL Direct: <0.5 mg/dL |

Increased; jaundice seen with plasma bilirubin levels >3 mg/dL |

| Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (aspartate aminotransferase) | 10–40 units/L | Increased |

| Serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (alanine aminotransferase*) | 5–35 units/L | Increased |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LD-5*) | 5.3%–13.4% | Increased |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 87–250 units/L | Normal; used to differentiate biliary obstruction |

| Albumin | 3.3–4.5 g/dL | Decreased; levels <2.5 g/dL are precarious |

| Ammonia | <50 g/dL | Increased ammonia converted to urea by the normal liver |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 7–20 mg/dL | Normal or decreased by impaired excretion of sodium and retention of water; increased in hepatorenal syndrome |

| Creatinine | 0.6–1.3 mg/dL | Increased in hepatorenal syndrome |

| Sodium | 135–145 mEq/L | Usually decreased; increased sodium may result after the administration of lactulose or if replacement of free water is inadequate |

| Potassium | 3.6–5 mEq/L | Decreased; related to the secondary effects of hyperaldosteronism, vomiting, diuretic use, or inadequate replacement; increased potassium may result from the use of blood products |

| Magnesium | 1.6–3 mEq/L | Decreased |

| Calcium | 8.8–10.4 mg/dL | Decreased |

| Phosphorus | 2.5–4.5 mg/dL | Decreased |

| Glucose | 70–110 mg/dL | Decreased; related to impaired gluconeogenesis and decreased insulin clearance |

Clinical manifestations

No matter the exact cause of the patient’s liver failure, it inevitably affects the entire physiologic makeup. Physical examination is important for the approximation of liver and spleen size, evidence of bleeding abnormalities, identification of extravascular fluid shifts, and any other organ dysfunction. Listed in the table below are common clinical features of hepatic failure and their associated causes.

Clinical Features of Hepatic Failure and Associated Causes

| Clinical Feature | Cause |

| Anemia | Iron, vitamin B12, or folate deficiency; hypersplenism; bone marrow suppression |

| Ascites | Portal hypertension; hypoalbuminemia; sodium and water retention |

| Fetor hepaticus (pungent sour odor detected in exhaled breath) | Inability to metabolize methionine |

| Gynecomastia | Increased circulating estrogen |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (hepatic coma) | Inability to metabolize ammonia; increased cerebral sensitivity to toxins; hypoglycemia |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Decreased renal blood flow, particularly to the cortex; vasoconstriction; decreased glomerular filtration rate; renal retention of sodium |

| Increased bleeding tendencies, nosebleeds, gingival bleeding, menstrual bleeding, easy bruising | Anemia; thrombocytopenia; decreased production of clotting factors; decreased adherence of circulating platelets |

| Increased risk of infection | Endotracheal intubation with impaired cough reflex; intravenous catheters; central lines; urinary catheters; leukopenia; decreased neutrophil adherence; complement deficiencies |

| Increased skin pigmentation | Increased activity of melanocyte-stimulating hormone |

| Jaundice | Increased circulating bilirubin |

| Leukopenia | Hypersplenism; bone marrow suppression |

| Palmar erythema | Increased circulating estrogen |

| Pectoral and axillary alopecia | Increased circulating estrogen |

| Peripheral edema | Hypoalbuminemia; failure of the liver to inactivate aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone, with subsequent sodium and water retention |

| Spider angiomas, “nevi” | Increased circulating estrogen |

| Testicular atrophy | Increased circulating estrogen |

| Thrombocytopenia | Hypersplenism; bone marrow suppression |

| Weight loss and muscle wasting | Nausea and vomiting; anorexia; impaired gluconeogenesis; impaired insulin functioning; hypoproteinemia |

Treatment

Management of patients with liver failure should include admission to the intensive care unit. The health care team should be on constant guard for complications associated with liver failure, such as sepsis, cerebral edema, hypoglycemia, and electrolyte and bleeding abnormalities. Liver failure associated with acetaminophen poisoning or mushroom poisoning should be identified immediately because antidotes are available for both. Patients who are not responsive to conventional treatment should be considered for liver transplantation as early as possible before they are excluded by the development of infection or encephalopathic brain damage.

General treatment modalities for patients with liver failure include the following:

• Central venous pulmonary catheter

• Histamine-2 (H2) antagonist or sucralfate

• Blood glucose checks every 1 to 2 hours

• Periodic assessment of neurologic status (neurologic status may rapidly deteriorate because of increasing ammonia levels or increasing intracranial pressure)

• Monitoring of renal function and fluid status

• Increase in gastric pH and decrease in risk of gastrointestinal bleeding

• Prevention of hypoglycemia and guiding administration of intravenous dextrose

• Prevention of aspiration pneumonia and adult respiratory distress syndrome

• Early nutritional supplementation: prevention of nutrition-related complications

Anesthetic considerations

Only surgery to correct life-threatening conditions should be performed on patients with liver failure. The patient’s condition should be optimized before the surgical procedure. A normally “minor” procedure can become a major catastrophe in patients with liver failure.

Premedication must be considered, taking into account the severity of the patient’s disease process, the presence of altered consciousness, and the liver’s diminished ability to metabolize pharmacologic agents. If the patient is thought to have a full stomach, antacids and H2 antagonists may be administered.

Monitoring should conform to the established standards of care. The size and number of intravenous catheters should be individualized. Most cases involving liver failure require the use of an arterial line, a central venous pressure or pulmonary artery catheter, and a urinary drainage catheter to monitor the patient’s fluid status.

The use of local anesthesia with sedation or regional anesthesia should be considered whenever possible. Coagulopathies must first be ruled out, and the surgical procedure itself must be considered. Patients may be considered to have a full stomach, especially in the presence of ascites. In this case, a rapid-sequence induction is standard. The choice of induction agent and dosage administered should reflect the liver’s diminished ability to metabolize pharmacologic agents and the patient’s increased volume of distribution. Hyperammoniaemia causes central nervous system inhibition, resulting in increased sensitivity to anesthetic agents. Increased ammonia also causes myocardial depression, which can be potentiated and cause severe hypotension when inhalation agents are administered.

Both nondepolarizing and depolarizing muscle relaxants may be administered. Dosages may need to be individualized according to the patient’s initial response. A peripheral nerve stimulator aids the practitioner in gauging the patient’s response and adjusting subsequent doses. The breakdown of succinylcholine remains relatively normal despite advanced disease states. Muscle relaxants metabolized by the liver (e.g., vecuronium) should be avoided. Cisatracurium may be the muscle relaxant of choice because of its unique metabolic properties, which do not involve either the liver or the kidneys. If cisatracurium is unavailable, any other nondepolarizing muscle relaxant may be used, taking into account the patient’s specific organ involvement and the drug’s metabolic properties.

Isoflurane and desflurane are the inhalational agents of choice. Nitrous oxide may be safely instituted according to the nature of the surgical procedure and as long as a high fraction of inspired oxygen is not required.

The use of opioids must take into account a prolonged half-life and decreased clearance. Because fentanyl does not decrease hepatic blood flow, it is often the opioid of choice for the patient with liver failure.

The patient with liver failure is at risk for major blood loss with any invasive procedure. Blood products should be available, and all losses should be replaced accordingly.

Prognosis

In the United States, mortality rates from liver disease have increased since the 1960s. Overall, the mortality rate from hepatic failure is 70% to 95%. Liver transplantation should be considered when conventional medical management fails; such consideration should take place early before infection or encephalopathic brain damage renders the potential candidate ineligible for the procedure. One-year patient survival rates after liver transplantation are 63% to 78%.

C Hepatitis

Acute hepatitis presents a variable clinical picture. Manifestations may extend from mild inflammatory increases in serum transaminase levels to fulminant hepatic failure.

Pathophysiology

The cause of this syndrome is usually exposure to an infectious virus. Other causes include exposure to hepatotoxic substances and adverse drug reactions. Viral hepatitis may be attributable to exposure to one of a number of viruses, including hepatitis viruses (A, B, C [formerly referred to as non-A, non-B], D [delta virus], E [enteric non-A, non-B]), Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and coxsackievirus. The most common culprits are hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. Hepatitis A and E are transmitted by the oral–fecal route, and hepatitis B and C are transmitted by contact with body fluids and physical contact with disrupted cutaneous barriers.

Clinical manifestations

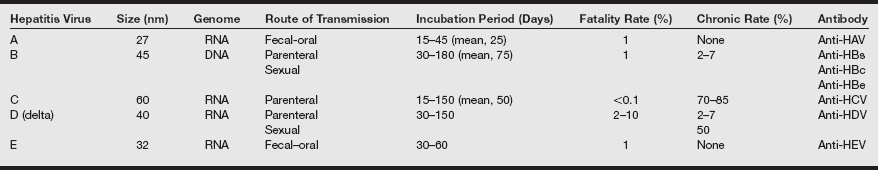

The common clinical course of viral hepatitis begins with a 1- to 2-week prodromal period, the signs and symptoms of which include fever, malaise, and nausea and vomiting. Progression to jaundice typically occurs, with resolution within 2 to 12 weeks. However, serum transaminase levels often remain increased for up to 4 months. If hepatitis B or C is the cause, the clinical course is often more prolonged and complicated. Cholestasis may manifest in certain cases. Fulminant hepatic necrosis in certain individuals is also possible. The major characteristics of hepatitis types A, B, C, D, and E are listed in the table on pg. 141.

Five Causes of Acute Viral Hepatitis

anti-HDV, Hepatitis D virus antibody; anti-HEV, hepatitis E virus antibody; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBc, hepatitis B core; HBe, hepatitis B e antigen; HBs, hepatitis B surface; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

From Hoofnagle JH: Acute viral hepatitis. In Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil’s Textbook of Medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008: 1101.

Acute viral hepatitis may evolve into a chronic active syndrome, which develops in 3% to 10% of cases involving hepatitis B and in 10% to 50% of cases involving hepatitis C. Many patients become asymptomatic infectious carriers of hepatitis B and C. These patients include many who are immunosuppressed or require chronic hemodialysis.

Drug-induced hepatitis

Drug-induced hepatitis results from an idiosyncratic drug reaction, from direct hepatic toxicity or from a combination of the two, as shown in the box below. Clinically, its manifestations resemble those of viral hepatitis, thereby complicating diagnosis. Alcoholic hepatitis is probably the most common form of drug-induced hepatitis and results in fatty infiltration of the liver (causing hepatomegaly), with impairment in hepatic oxidation of fatty acids, lipoprotein synthesis and secretion, and fatty acid esterification.

Chronic hepatitis

Chronic hepatitis occurs in 1% to 10% of acute hepatitis B infections and in 10% to 40% of hepatitis C infections. Patients are classified as having one of three distinct syndromes based on liver biopsy:

Chronic persistent hepatitis is relatively benign and is confined to portal areas. Hepatocellular integrity is preserved, and progression to cirrhosis is rare. Chronic lobular hepatitis involves recurrent exacerbations of acute inflammation, but as in persistent hepatitis, progression to cirrhosis is rare. The most serious form of chronic hepatitis is chronic active hepatitis, which is progressive and results in hepatocyte destruction, cirrhosis, and ultimately hepatic failure. Death often results from related manifestations of hepatic failure, such as hemorrhage from esophageal varices, multiorgan system failure (e.g., hepatorenal syndrome), and encephalopathy. The typical etiologic agent is hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus. Autoimmune disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus) and exposure to certain drugs (e.g., methyldopa, isoniazid, and nitrofurantoin) have been implicated as etiologic factors as well.

Clinical manifestations

Marked fatigue and jaundice are common in chronic hepatitis. Arthritis, neuropathy, myocarditis, thrombocytopenia, and glomerulonephritis may also be present. Plasma albumin levels are usually decreased, and the prothrombin time (PT) is often prolonged.

Treatment

Dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities should be corrected. Vitamin K or FFP is used to correct coagulopathies. Bacterial infections should be treated, and neomycin, lactulose, or both should be used to decrease plasma ammonia levels. Factors that may aggravate hepatic encephalopathy should be avoided. Orthotopic liver transplantation may be considered in selected patients.

Anesthetic considerations

Increased perioperative mortality (10%) and morbidity (12%) rates have been reported with surgery, particularly laparotomy, in patients with acute viral hepatitis. Operative procedures performed in patients with alcohol intoxication are also likely to be associated with increased perioperative complications. Surgery performed in those undergoing alcohol withdrawal is associated with a mortality rate as high as 50%.

With acutely intoxicated alcoholic patients, certain anesthetic issues must be kept in mind: (1) less anesthetic is needed; (2) aspiration precautions must be implemented; (3) surgical bleeding may be increased as a result of interference with platelet aggregation; (4) the brain is less tolerant of hypoxia; and (5) the level of circulating catecholamines is increased, as evidenced by lability in vital signs and exaggerated responses to drugs and stimuli (probably indicating decreased neurotransmitter uptake).

It is recommended to postpone elective surgical procedures until liver function has been normalized. Surgery and anesthesia greatly increase the risk for further hepatic decompensation in patients with hepatitis; this risk may be compounded by the development of renal failure (hepatorenal syndrome), encephalopathy, and the decompensation of other organ systems.

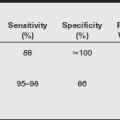

If urgent or emergency surgery is necessary, as thorough a preoperative history as possible must be obtained. If serious time constraints are imposed, the preoperative evaluation should focus on signs and symptoms (e.g., encephalopathy, bleeding diatheses, jaundice, ascites, and hemodynamic findings) and on the results of laboratory studies (e.g., levels of electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum glucose, hemoglobin, hematocrit, liver enzymes, and bilirubin, as well as arterial blood gas determinations and coagulation studies). Other pertinent studies include chest radiography and ECG. If not previously ordered, blood typing and crossmatching are warranted, depending on the magnitude of the planned procedure. Any history of hospitalizations and anesthetic use also should be obtained. In general, as much pertinent information as possible should be procured and recorded.

Dehydration and electrolyte derangements should be anticipated and corrected before surgery. Metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia are often present as a result of vomiting. The presence of hypomagnesemia predisposes to the development of perioperative dysrhythmias. Elevated enzyme (e.g., alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST]) and serum bilirubin levels are nonspecific with regard to the degree of hepatic necrosis. Alcoholic hepatitis and obstructive hepatitis are commonly associated with an elevation in AST. Viral hepatitis and drug-induced hepatitis often reflect elevated ALT levels. The highest measured levels of AST are seen in viral hepatitis or in fulminant hepatic failure.

The PT is the best indicator of the liver’s ability to synthesize coagulation factors. Severe hepatic dysfunction results in a persistent prolongation of PT even after the administration of vitamin K. Evaluation of serum albumin level is warranted, although deficiencies in serum albumin, as well as in all proteins synthesized by the liver (i.e., coagulation factors), are manifestations of severe hepatic dysfunction and malnutrition.

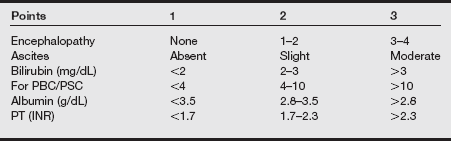

Preoperative medication (e.g., sedation) may best be avoided, so that exacerbation of preexisting encephalopathy or respiratory depression is prevented. Administration of FFP, vitamin K, and packed red blood cells may be necessary for the correction of coagulopathy and red blood cell deficiency before surgery. Premedication with benzodiazepines and thiamine may be necessary for alcoholic patients in impending withdrawal. Child’s classification system is useful in conjunction with other available assessment parameters for determining the degree to which liver disease influences surgical and anesthetic risk (see table below).

| Laboratory Study | Normal |