Neonatal anesthetic considerations

A Preoperative assessment

The perioperative management of any neonate is determined by the nature of the surgical procedure, the gestational age at birth, the postconceptual age at surgery, and associated medical conditions.

1. Gestational age and postconceptual age at surgery

a) The gestational age and postconceptual age are critical to the determination of the physiologic development of the neonate. The history of the delivery and the immediate postdelivery course can influence the choice of anesthetic technique and assist in anticipating possible postoperative complications.

b) Preterm neonates are classified as borderline preterm (36-37 weeks’ gestation), moderately preterm (31-36 weeks’ gestation), and severely preterm (24-30 weeks’ gestation).

c) Neonates can be classified according to their weight as well as their gestational age. Full term is considered to be 37 to 42 weeks’ gestation.

d) However, even full-term neonates who are small for gestational age (SGA) often present with conditions requiring surgical intervention. SGA neonates have different pathophysiologic problems from preterm infants (<37 weeks’ gestation) of the same weight.

e) Gestational age and neonatal problems are closely related. Maternal health problems also can have significant implications for preterm as well as full-term (even SGA) neonates.

f) Several common maternal problems and the possible associated neonatal sequelae are listed in the following table.

Maternal History with Commonly Associated Neonatal Problems

| Maternal History | Anticipated Neonatal Sequelae |

| Rh-ABO incompatibility | Hemolytic anemia |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | |

| Kernicterus | |

| Toxemia | Small birth weight and associated problems |

| Muscle relaxant interaction after magnesium therapy | |

| Hypertension | Small birth weight |

| Infection | Sepsis, thrombocytopenia, viral infection |

| Hemorrhage | Anemia, shock |

| Diabetes | Hypoglycemia, birth trauma, macrosomia, small birth weight |

| Polyhydramnios | TE fistula, anencephaly, multiple anomalies |

| Oligohydramnios | Renal hypoplasia, pulmonary hypoplasia |

| Cephalopelvic disproportion | Birth trauma, hyperbilirubinemia, fractures |

| Alcoholism | Hypoglycemia, congenital malformation, fetal alcohol syndrome, small birth weight |

From Cote CJ, Ryan JF, Todres ID, ed. A practice of anesthesia for infants and children. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993:41.

a) Because of advances in neonatal medicine, many preterm babies born at exceptionally early gestational age and extremely low birth weights are surviving to be challenged with a plethora of unique diseases and pose many anesthetic challenges.

b) Prematurity presents its own set of complications, which include anemia, intraventricular hemorrhage, periodic apnea accompanied by bradycardia, and chronic respiratory dysfunction.

c) Postconceptual age (gestational age + postnatal age) should be determined at the time of the anesthetic evaluation. Premature infants of less than 60 weeks’ postconceptual age have the greatest risk of experiencing postanesthetic complications.

d) The manifestations of prematurity are thought to occur as a result of inadequate development of respiratory drive and immature cardiovascular responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia.

e) Premature infants have a significant risk of postoperative apnea and bradycardia during the first 24 hours after general anesthesia.

f) The contributing factors that may influence the occurrence of apnea in premature infants are listed in the following box.

a) The incidence of apnea in the postoperative period is inversely related to postconceptual age and is most frequent in infants of less than 60 weeks of postconceptual age.

b) Apnea may still occur when regional anesthetic techniques have been substituted for general anesthesia.

c) Premature infants without a history of apnea or bradycardia may still experience postoperative apnea.

d) Premature infants with histories of respiratory distress, concurrent respiratory disease, and periods of apnea are twice as likely to develop postoperative apnea.

e) Concurrent anemia (hematocrit <30%) places additional risk for the occurrence of postoperative apnea.

f) Outpatient surgical care is usually not an acceptable venue for premature infants. Although the literature supports an increased risk for premature infants up to 60 weeks of postconceptual age, debate continues as to when this risk decreases.

g) Perioperative use of caffeine: The standard doses of caffeine and theophylline are 10 mg/kg and 6 mg/kg, respectively. Both have been shown to reduce the incidence of idiopathic apnea of prematurity and reduce the occurrence of apnea after surgery in premature infants.

4. Preanesthetic assessment and neonatal anesthetic implications

a) Valuable information is obtained from those caring for the baby in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). It is often best to alter the infant’s plan of therapy as little as possible (e.g., management of ventilation, acid-base status, and glucose). Consultation with the neonatologist is helpful.

b) A maternal drug history is very important. In presence of illicit drugs, such as heroin and cocaine, the baby could be withdrawing from the drug at the time of surgery. Particularly with cocaine, there is an increased incidence of pulmonary hypertension and bowel perforation.

c) Some mothers take large doses of aspirin or acetaminophen during pregnancy. Their infants could also exhibit pulmonary hypertension and persistent fetal circulation during the first few days of life.

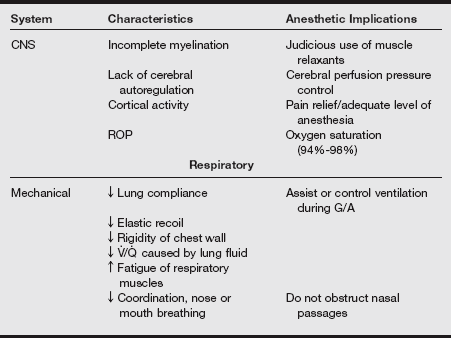

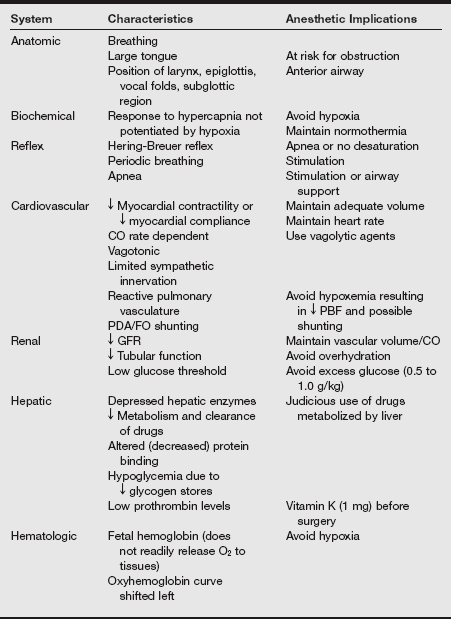

d) All of the information gathered during the assessment leads to the anesthetic plan based on the implications of all the transitioning body systems. The characteristics of the body system and the anesthetic implications are listed in the following table.

Preanesthetic Assessment and Neonatal Anesthetic Implications

CNS, central nervous system; FO, foramen ovale; G/A, general anesthesia; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; RPO, retinopathy of prematurity; V./Q., ventilation/perfusion.

5. System review and examination

a) When performing a physical assessment, one should look carefully for congenital anomalies. A rule of thumb is that if there is one anomaly present, there are probably more because many occur in clusters, labeled a syndrome.

b) These problems can occur most often in SGA and large-for-gestational-age (LGA) neonates and should be analyzed and understood as listed in the box on pg. 529.

6. Head and neck abnormalities

a) Any abnormality of the head or neck should raise concerns regarding airway management. The shape and size of the head, with or without the presence of pathology, can make airway management difficult. A small mouth and large tongue can obstruct the airway during mask ventilation.

b) Neonates have very small nares, and when obstructed by an anesthesia face mask, they do not convert to mouth breathing, particularly if the mouth is being held closed.

c) A nasogastric tube can obstruct half of the neonate’s airway and should be placed orally. A small or receding chin, as seen in Pierre Robin and Treacher Collins syndromes, may make direct laryngoscopy and visualization of the glottis impossible, requiring other types of airway management.

d) Cleft lip, with or without cleft palate, may complicate intubation. Anomalies such as cystic hygroma or hemangioma of the neck can produce upper airway obstruction. In the case of a preterm neonate, it should also be determined if the patient has retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), cataracts, or glaucoma.

e) Atropine administration could result in significant increases in intraocular pressure and further damage to the eye.

7. Respiratory system abnormalities

a) Surfactant, which inhibits alveolar collapse, peaks between 35 and 36 of gestational age. Premature neonates are at dramatically increased risk for respiratory failure.

b) The incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is inversely related to gestational age at birth.

c) The onset of RDS can be as early as 6 hours after birth; symptoms include tachypnea, retractions, grunting, and oxygen desaturation.

d) Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is a disease of newborns that manifests as a need for supplemental oxygen along with lower airway obstruction and air trapping, carbon dioxide retention, atelectasis, bronchiolitis, and bronchopneumonia.

e) Oxygen toxicity, barotrauma of positive-pressure ventilation on immature lungs, and endotracheal intubation have been reported as causative factors. Management of the patient’s oxygenation can be challenging.

f) Careful monitoring of the acid-base status and the use of increased peak inspiratory pressure and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) may be needed to maintain oxygenation during surgery.

8. Cardiovascular system abnormalities

a) In evaluation of the neonate’s cardiovascular system, several variables should be examined, including heart rate, blood pressure patterns, skin color, intensity of peripheral pulses, and capillary filling time.

b) The presence of a murmur or abnormal heart sound, low urine output, metabolic acidosis, dysrhythmias, or cardiomegaly, alone or in combination, raises the concern of some type of congenital heart lesion. These patients should be evaluated with chest radiography, electrocardiography (ECG), and echocardiography. The results of these diagnostic tests allow for effective planning of the anesthetic, decreasing the possibility of complications.

c) The common syndromes associated with cardiac defects are listed in the following table.

Syndromes Associated with Cardiac Defects

| Syndrome or Malformation | Cardiac Defect | Other Associated Conditions |

| Beckwith-Wiedemann | Miscellaneous | Macroglossia, exomphalos, hypoglycemic |

| CHARGE syndrome | Tetralogy of Fallot, PDA, double outlet RV with AV canal, ASD, VSD | Choanal atresia, micrognathia, coloboma, cleft palate |

| Treacher Collins | Miscellaneous | Facial and pharyngeal hypoplasia, microsomia, cleft palate, choanal atresia |

| VACTERL | VSD | Vertebral anomalies, TEF, renal anomalies, imperforate anus, absent radius |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) | AV canal, ASD, VSD, PDA, TOF | Bowel atresia, large tongue, atlanto-axial instability |

| Trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) | VSD, PDA | Micrognathia, renal malformations |

| Trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome) | VSD, dextrocardia, ASD | Microcephaly, micrognathia, cleft lip and palate |

ASD, atrial septal defect; AV, atrioventricular; CHARGE, coloboma of the eye or central nervous system anomalies, heart defects, atresia of the choanae, retardation of growth or development, genital or urinary defects, and ear anomalies or deafness; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; RV, right ventricle; TEF, tracheoesophageal fistula; TOF, Tetralogy of Fallot; VATERL, vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheoesophageal fistula, renal abnormalities, and limb malformations; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

From Peutrell JM, Weir P. Basic principles of neonatal anesthesia. In Hughes DG, Mathes, S, Wolf A, eds. Handbook of neonatal anesthesia. London: Saunders; 1996:166.

d) Anesthetic implications of congenital heart disease in neonates include the following:

9. Central nervous system abnormalities

a) An assessment of the central nervous system (CNS) should include the status of the infant’s intracranial pressure (ICP) and intracranial compliance.

b) Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) is almost exclusively seen in preterm babies; this occurs when there is spontaneous bleeding into and around the lateral ventricles of the brain.

c) The more preterm the neonate and the smaller the weight, the more likely one could find IVH.

d) The hemorrhage is usually the result of RDS, hypoxic-ischemic injury, or episodes of acute blood pressure fluctuation that rapidly increase or decrease cerebral blood flow. The classic example is laryngoscopy in the presence of inadequate anesthesia.

e) The symptoms of IVH include hypotonia, apnea, seizures, loss of sucking reflex, and a bulging anterior fontanel. Particular evaluation of a neonate with meningomyelocele (spina bifida) is discussed subsequently.

10. Preoperative laboratory studies

Neonates who are premature (<60 weeks of postconceptual age), those with concurrent cardiopulmonary disease, and babies in whom major blood loss is anticipated during the surgical procedure should have serial hematocrits, electrolytes, blood gases, glucose levels, and serum osmolality measured. The test values will assist in the fluid, electrolyte, and blood replacement during the surgical procedure.

11. Preoperative treatment of significance for anesthesia

Many of the preexisting conditions in neonates require medical treatment. Some of the preoperative drugs and their anesthetic implications are listed in the following table.

Preoperative Treatment of Significance for Anesthesia

| Drug | Implication |

| Diuretics for heart failure, BPD | Hypokalemia |

| Digoxin for heart failure | ECG abnormalities |

| Steroids for BPD | Hyperglycemia |

| Immunocompromised | |

| Anticonvulsants | Cardiac arrhythmia |

| Potent inducer of hepatic enzymes | |

| Indomethacin | Increased risk of bleeding |

| Displaced bilirubin from protein binding sites | |

| Transient hyponatremia | |

| Renal impairment | |

| Theophylline or caffeine | Significant toxic side effects: convulsions, tachycardia, tremor |

| Prostaglandins E1 or E2 | Ventilatory depression and apnea |

| Hypotension | |

| Cerebral irritability | |

| Seizures | |

| Tachycardia | |

| Pyrexia | |

| Tolazoline | Systemic hypotension |

| Cardiac irritability | |

| Transient oliguria | |

| Increased gastric acid | |

| Prostacyclin | Hypotension |

| Inhibition of platelet aggregation | |

| Rebound PPHN with withdrawal |

BPD, Bronchopulmonary dysplasia; ECG, electrocardiography; PPHN, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.

a) Parental preparation is important. In the case of institutions that do not have a NICU, the patient will have been transferred in from another institution, and the parents still may be in the institution where the baby was delivered.

b) It is imperative that the parents be prepared and the informed consent for anesthesia be obtained. Often this must be done via telephone or from the father, who may have accompanied the neonate to the NICU.

c) The anxiety of the parents of a newborn or neonate with a serious illness requiring surgical intervention is very high. The anesthesia provider fosters trust and confidence through a courteous and understandable explanation of the anesthetic experience.

B Regional anesthesia in neonates

a) Regional anesthesia in neonates is an acceptable option when the risks of complications during or after general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation are very high for anatomic or physiologic reasons.

b) These techniques have allowed surgical procedures to be done on critically ill neonates under minimal general anesthesia, with considerable reduction in the need for CNS depressant drugs.

c) An additional benefit to the use of regional anesthesia in this age group is postoperative pain control. The two most common techniques used in neonates are the spinal and caudal epidural blocks.

d) Anatomic differences in the neonate should be considered, particularly the location of the terminal end of the spinal cord, the dural sac, and the volume of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

e) The spinal cord extends as far as L3 in newborns and neonates and does not reach the adult position of L1 until 1 year of age. The dural sac extends to S3 to S4 in these babies and does not reach the adult position of S1 until approximately 1 year of age.

f) The volume of CSF is twice that of adults (4 mL/kg vs. 2mL /kg, respectively). This dilutes the local anesthetics injected and could explain the higher dose requirements and shorter duration of analgesia.

g) Bradycardia and hypotension are not often seen. It is thought that this could be because of the immature sympathetic nervous system or the proportionately small blood volume in the lower limbs, decreasing the amount of venous pooling.

h) The ventilatory response to the regional anesthetic is related to the level of the block. With a level as high as T2 to T4, there could be intercostal muscle weakness that requires the dependence on diaphragmatic movement for tidal breathing; however, tidal volume and respiratory rate are not usually affected.

i) There are pharmacologic considerations when regional anesthesia is used in neonates. The extracellular space is larger. This means the initial dose of local anesthetic is diluted into a larger volume of distribution, resulting in a lower initial plasma peak concentration.

j) Neonates have diminished concentrations of albumin and alpha acid glycoprotein, resulting in reduced protein binding of local anesthetics and significant increases in the concentration of free drug, which could increase the risk of CNS and cardiac toxicity.

k) Local anesthetics, particularly the amides, are broken down slower in newborns and neonates because of immature hepatic degradation. The major elimination pathway for ester local anesthetics is hydrolysis via plasma cholinesterases, and these levels are lower in neonates as well.

l) Demonstrations of the previous differences are shorter duration of blocks compared with adults and larger initial doses of local anesthetic per kilogram to achieve the same extent of blockade.

m) Most neonates have a regional technique performed after the induction of general anesthesia because of the age of the patient and the possibility of agitation and continuous movement affecting the placement and success of the block.

n) The possible complications of regional anesthesia in newborns and neonates that have been reported by several sources are neurologic injury caused by intraneural injection of local anesthetic and the decreased ability to detect intravascular injection of local anesthetic.

o) The use of ultrasonography has decreased the risk of complications associated with the placement of spinal and epidural needles and catheters as well as monitoring the spread of local anesthetics.

p) It is difficult to assess a dermatome level because these patients are nonverbal.

a) Spinal anesthesia can be performed in the sitting or lateral position; however, the neck should be extended to prevent airway obstruction.

b) The lumbar puncture is performed at the L3 to L4 or L4 to L5 interspace because the spinal cord ends at L3 in neonates.

c) A 1½-inch, 22-gauge needle is inserted and, even with this small needle, one should be able to feel resistance when the needle enters the ligamentum flavum and the characteristic “pop” when the needle enters the subarachnoid space. The distance is approximately 1 cm.

d) The most common local anesthetics are tetracaine 1% and bupivacaine 0.5% to 0.75% at doses of 0.4 to 1.0 mg/kg. When the local anesthetic is injected, the neonate should be immediately placed in the supine position, and the legs should be secured with tape to prevent them from being raised for any reason.

a) Caudal anesthesia is the most commonly used regional block in pediatric anesthesia. It can be used for any procedure involving innervation from the sacral, lumbar, or lower thoracic dermatomes.

b) In youngest patients, the caudal block can be used as an adjunct to general anesthesia or solely for postoperative analgesia.

c) In neonates, it is most often placed after induction of general anesthesia before the beginning of the surgical procedure.

d) The patient is placed in the lateral position with the upper knee flexed. The landmarks are identified: the tip of the coccyx to fix the midline and the sacral cornua on either side of the sacral hiatus.

e) These landmarks form the points of an equilateral triangle with the tip resting over the sacral hiatus.

f) A 22-gauge needle is placed, bevel up, at a 45-degree angle to the skin.

g) When the sacrococcygeal membrane is punctured, a distinctive loss of resistance is felt, and the angle of the needle is reduced and advanced cephalad.

h) The syringe is aspirated, and if there is no CSF or blood, the local anesthetic can be administered. Any local anesthetic can be used, and the volume of the local anesthetic determines the height of the block.

i) Volumes of 1.2 to 1.5 mL/kg provide analgesia and anesthesia to the T4 to T6 dermatome.

j) No matter which local anesthetic is used, the concentration is adjusted to deliver no more than 2.5 mg/kg.

k) The addition of epinephrine (1:200,000) or clonidine (1 to 2 mcg/kg) will prolong the block significantly.

l) Opioids such as morphine or fentanyl can be added to the caudal dose of local anesthesia to provide additional analgesia, however, when these medications are used, the patient should be monitored for respiratory depression up to 24 hours after injection.

m) Any regional technique can theoretically be used in neonates, with careful attention to the potential for toxicity of local anesthetics and careful dosing parameters.

C Anesthetic considerations for selected cases

Pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis is an obstructive lesion, characterized by the “olive-shaped” enlargement of the pylorus muscle. It is a common gastrointestinal anomaly, particularly in boys. It is usually diagnosed between 2 and 12 weeks of life. Clinical symptoms include nonbilious postprandial emesis, becoming more projectile with time; a palpable pylorus; and visible peristaltic waves. The procedure to correct the problem is a pyloromyotomy.

Historically, pyloric stenosis was considered a surgical emergency; however, as with medical progress on many fronts, the procedure is now treated as a medical emergency with the patient being optimized before elective surgery. Fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance should be corrected before anesthesia. Hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and metabolic alkalosis are the most common electrolyte abnormalities.

a) Before induction, the neonate’s stomach must be emptied via orogastric tube. Some anesthesia providers irrigate the stomach via the orogastric tube with warm normal saline until the aspirate is clear and minimal. Others tilt the baby in various directions to evacuate the remaining contents.

b) After preoxygenation, the induction should be a modified rapid sequence with properly applied cricoid pressure and gentle positive-pressure ventilation via mask. (Many practitioners still perform an awake oral or a true rapid sequence.)

c) Oral endotracheal intubation is mandated to protect the airway from any gastric contents that may be residual.

d) Maintenance can be with inhalation anesthetics or in combination with intravenous (IV) drugs.

e) These babies should be extubated awake.

f) Postoperatively these patients, particularly a preterm or SGA neonate, could exhibit drowsiness, lethargy, or apnea. This could be attributed to electrolyte abnormalities or postconceptual age.

Inguinal hernia

Inguinal hernias are particularly prevalent in preterm infants. The surgical problem presents the possibility of incarceration of the small bowel in the hernia defect, resulting in ischemia and tissue death. Also of concern is the potential injury to the ipsilateral testicle. These babies routinely have their hernia repair before discharge from the NICU, and the anesthesia provider is faced with all the usual problems of prematurity, such as BPD. The surgical approach can be the standard abdominal incision; in some centers, laparoscopy is the preferred technology. In most situations, the contralateral side is explored to rule out the presence of another defect because of the high incidence of bilateral involvement. When this procedure is performed by a urologist, the contralateral side is most often not explored.

a) Because of the many possible patient issues, the anesthetic technique must be tailored for each patient.

b) Inhalation or IV induction is acceptable as well as airway management with a mask, laryngeal mask airway, or endotracheal tube (ETT).

c) The use of the laparoscopic approach necessitates the use of an ETT.

d) Maintenance can be with inhalation anesthetics or in combination with IV drugs.

e) Small neonates who are at risk for postoperative apnea and bradycardia may benefit from spinal anesthesia.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

A congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a defect of the diaphragm that allows extrusion of the abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity. This disorder has an incidence of one in 2500 live births. The herniated abdominal contents act as a space-occupying lesion and prevent normal lung growth and development. Most of these defects are left sided via the foramen of Bochdalek, and the lung affected to the greatest extent is on the ipsilateral side. However, the other lung can be affected as well. The lungs have reduced sized bronchi, less bronchial branching, decreased alveolar surface area, and abnormal pulmonary vasculature. There is a thickening of the arteriolar smooth muscle extending to the capillary level of the alveoli. This results in increased pulmonary artery pressure and causes right-to-left intrapulmonary shunting.

Neonates with CDH present immediately after birth with a classic triad that includes cyanosis, dyspnea, and dextrocardia. Other symptoms include tachypnea, absence of breath sounds on the affected side, and severe retractions. Their physical appearance is a scaphoid abdomen and a barrel chest. Diagnosis is confirmed by chest radiographs documenting bowel in the thoracic cavity and a gasless abdominal cavity. Between 44% and 66% of neonates with CDH have other anomalies, particularly heart lesions.

The emergent nature of the repair has been recently reexamined, and more emphasis is now placed on the stabilization of the pulmonary hypertension and other medical issues. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is one method of bridging the gap between birth and surgical repair; however, it is not the mode of treatment for all patients.

a) A thorough assessment of the baby, including laboratory, radiographic, and physical symptoms, is mandatory.

b) Listening to breath sounds will assist in evaluating the degree of ventilation on each side of the chest after intubation.

c) Because of the respiratory manifestations of the problem, the patient will be already intubated and have IV access and arterial lines in place when arriving in the operating room.

d) If the patient is not intubated, an ETT should be placed after a rapid-sequence induction. If a difficult airway is suspected, an awake intubation should be done.

e) It is important in these patients to administer an anticholinergic (atropine 0.02 mg/kg) IV just before induction to prevent the bradycardia during induction.

f) If an awake intubation is planned, some type of analgesia should be used to decrease the stress response of airway instrumentation.

g) Ventilation should be delivered gently to avoid inflating the stomach with air, further compromising the pressure in the chest. Volutrauma can be avoided by delivering small tidal volume and PEEP if necessary.

h) The patient’s hemodynamic stability should determine the anesthetic drugs used. A high-dose narcotic technique is commonly used (fentanyl, 15-25 mcg/kg) if tolerated.

i) The use of inhalation agents must be judicious because they pose significant risk to the baby’s cardiovascular stability.

j) Nitrous oxide should be avoided because it will increase the volume of gastrointestinal tissue and further impair ventilation.

k) Monitoring must include blood pressure, ECG, pulse oximetry, capnography, temperature, and heart rate.

l) To monitor for right-to-left cardiac shunting, oximeter probes should be placed preductal (right upper extremity) and postductal (lower extremity).

m) The use of arterial blood pressure monitoring not only allows beat-to-beat assessment of blood pressure but also provides an outlet for easier blood sampling.

n) All conditions that can increase pulmonary vascular resistance (hypoxia, hypothermia, or acidosis) should be avoided.

o) Carbon dioxide should be kept at normal or slightly elevated levels, and oxygen saturation should be maintained above 80 mmHg.

p) Any derangement of electrolytes should be corrected quickly, and any significant blood loss should be replaced.

q) In the event that cardiorespiratory instability prevents the neonate from being transported to the operating room, the anesthesia provider might be required to administer anesthesia in the NICU while the baby is still on ECMO.

r) Under these circumstances, the recommended anesthetic choice is an opioid and nondepolarizing muscle relaxant technique instead of an inhalation agent.

s) Postoperative ventilation is required with the goal of keeping the arterial oxygenation greater than 150 mmHg and slowing weaning to lower oxygen concentrations over a 48- to 72-hour period.

Omphalocele and gastroschisis

Omphalocele and gastroschisis present with similar physical findings, but they originate from distinct abnormalities that occur in utero. An omphalocele occurs from failure of portions of or the entire contents of the intestine to return to the abdominal cavity. In gastroschisis, the abdominal contents have already returned to the abdominal cavity, but ischemia from insufficient blood supply by the omphalomesenteric artery causes a defect at the base of the abdominal wall and thus extrusion of abdominal contents. It is more common to encounter omphalocele in term newborns and gastroschisis in preterm newborns. The primary difference in the two defects is the presence of a membrane (the peritoneum) covering the extruded abdominal contents in the baby with omphalocele and the lack of membrane in the baby with gastroschisis. They are often associated with other anomalies. These anomalies might be cardiac, genitourinary (bladder exstrophy), metabolic (e.g., Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, macroglossia, hypoglycemia, organomegaly, gigantism), malrotation, Meckel diverticulum, and intestinal atresia. When the omphalocele is in the epigastric region, cardiac and thoracic anomalies are more prevalent. If the omphalocele is located in the hypogastric area, cloacal anomalies and exstrophy of the bladder are seen more often. Both gastrointestinal anomalies, although very different in presentation, are almost identical in anesthetic management.

a) A newborn with an omphalocele or gastroschisis is usually brought to the operating room very soon after birth to minimize the possibility of infection, the loss of fluid and heat, and the possible death of bowel tissue.

b) A thorough preoperative evaluation must be done to identify the presence of any of the previously mentioned associated anomalies.

c) Historically, the surgical approach was to immediately attempt primary closure of the defect. This entailed placing a large amount of abdominal contents into a cavity that was not usually large enough, and the result was a significant increase in intraabdominal pressure that impeded ventilation and profound hypotension secondary to aortocaval compression.

d) Over the past decade, surgeons have opted for a staged closure using a Silastic silo as a temporary housing for the bowel. This silo is sutured to the defect, and the silo is reduced over the next 3 to 7 days to allow for accommodation of the gastric contents and abdominal wall stretching. Then the neonate is usually brought for complete closure.

e) In the event primary closure is attempted, it should be noted that excessive intraabdominal pressure can increase the possibility of unsuccessful completion of the closure, as shown in the following box.

f) The choice of anesthetic agent and technique is determined by several guiding principles: severe dehydration and massive fluid loss from exposed viscera and internal third spacing of fluid caused by bowel obstruction, hypothermia, the potential for sepsis and associated anomalies, and postoperative ventilation requirements.

g) It is common for the anesthesia provider to choose an opioid and nondepolarizing muscle relaxant technique; however, the abdominal wall may not allow primary closure even with the use of muscle relaxants.

h) Ventilatory compromise and decreased organ perfusion are major problems as intraabdominal pressure increases.

i) Adequate IV access is essential to infuse large amounts of fluid quickly and invasive monitoring guides the replacement.

j) A pulse oximeter probe on a lower extremity will indicate if there is compromise in the perfusion to the lower extremities caused by obstruction of venous return.

k) Postoperative ventilation will be mandatory on all of these babies requiring the continued use of paralytics and sedation with an opioid until their clinical status stabilizes.

Tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia

Esophageal atresia (EA), with or without tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), is normally diagnosed immediately after birth when an orogastric tube cannot pass into the stomach, there is coughing and choking after the first feeding, or after recurrent pneumonia associated with feedings. In the past, this condition was often lethal; however, today there is an expectation of almost 100% survival.

a) There is a significant association of other serious congenital anomalies in these babies. Some sources report as high as 30% to 50% of newborns with EA and TEF have other anomalies, particularly VACTERL (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac defects, TEF, renal abnormalities, and limb malformations) association.

b) EA with a distal fistula is the most common presentation of TEF in approximately 80% to 90% of patients.

c) The esophagus ends in a blind pouch, and the distal esophagus forms a fistula with the trachea, usually above the carina.

d) There are five other configurations of this anomaly, varied by the location of the fistula and the presence or absence of EA.

e) The morbidity and mortality of TEF are directly related to the resulting pulmonary complications from aspiration of feedings.

a) The focus of the preoperative preparation should be to minimize the pulmonary complications by discontinuing oral feedings, placement of a tube to suction nasopharyngeal secretions that accumulate in the blind esophageal pouch, maintain the infant in a semirecumbent position to minimize aspiration of secretions, and placement of a gastrostomy tube to prevent excess gastric distention from impairing ventilation, and to take measures to prevent dehydration.

b) The surgical procedure is performed via a thoracotomy incision, usually on the right side. The sequence of the repair is the ligation of the fistula and then anastomosis of the two ends of the esophagus, if possible.

c) Standard monitors should be used. The precordial stethoscope should be placed in the left axilla after induction to allow for monitoring of ventilation and heart sounds.

d) The cardiorespiratory condition of the neonate should dictate the use of more invasive monitoring techniques such as an arterial line (umbilical or radial). In the youngest critically ill patients, preductal and postductal oximeter probes may be used.

e) The technique of induction should be based on the clinician’s evaluation of the airway. When there is concern of a difficult airway, an “awake intubation” should be performed. This technique minimizes the gastric distention from anesthetic gases passing through the fistula and allows proper placement of the ETT without positive-pressure ventilation.

f) When airway management is determined to be “routine,” an inhalation induction with gentle positive-pressure ventilation and intubation can be used.

g) To further minimize stomach distention, spontaneous ventilation to an adequate depth of anesthesia followed by endotracheal intubation may be carried out.

h) If this technique is used, care must be taken to avoid hypoxemia that will result from the respiratory depression produced by high concentrations of inhalation agents.

i) Another accepted technique is the IV rapid-sequence induction with endotracheal intubation.

j) With any of the above-mentioned techniques, proper position must be verified after the ETT is placed. A common method of verifying the correct position is to actually intubate the right mainstem bronchus and then withdraw the ETT until breath sounds are heard on the left side of the chest. The tip of the tube is likely between the fistula and the carina.

k) If there is a gastrostomy in place, another method is to submerge the gastrostomy tube in water and, if there are bubbles on ventilation, the fistula is being ventilated and the tube must be repositioned.

l) The bevel of the ETT should be turned anteriorly to allow the posterior surface of the ETT to occlude the fistula.

m) In one configuration of TEF, the fistula is located very close to the carina. In this case, the ETT may need to be placed in the bronchus of the nonoperative lung until the fistula can be ligated. After ligation, the tube can be withdrawn to above the carina.

n) During the procedure, it is essential to monitor ventilation very carefully. Airway obstruction can occur if the trachea is compressed or if secretions or blood block the openings of the ETT. This must be corrected immediately.

o) The neonate without significant pulmonary complications, who is awake and moving vigorously, is most often extubated in the operating room.

p) Blood and secretions may be present in the ETT and should be suctioned gently before removal.

q) If there is any concern about airway obstruction or impaired ventilation, mechanical ventilation should be continued.

r) It is thought that if bag and mask ventilation or reintubation is required, undue stress could be placed on the suture lines of the repair with laryngoscopy and neck extension, resulting in damage to the esophagus and necessitating further surgical procedures.

s) Another problem that can occur with early extubation in smaller neonates is an inability to maintain the work of breathing because of preoperative lung disease.

t) If postoperative mechanical ventilation is needed, the ETT should be positioned 1 cm away from the fistula repair to allow for healing of the suture line.

u) A suction catheter should be clearly marked with a distance for insertion that approximates the distance just above the anastomotic repair.

v) Postoperative pain can be managed with opioids or a caudal epidural (or both) placed intraoperatively.

a) Complications may occur later that could influence anesthetic management.

b) Neonates who have had EA or TEF repair early in life can develop a diverticulum at the site of the old tracheal fistula. This could present problems in the future if inadvertent intubation of the diverticulum occurs.

c) Esophageal stricture could develop at the site of esophageal anastomosis, requiring repeated dilation or possible resection.

Malrotation and midgut volvulus

As the intestine is moving from its extraabdominal location during the first trimester of gestation, it can become twisted. The result can be a compromised superior mesenteric artery and intestinal ischemia. This ischemia can cause bowel strangulation, bloody stools, peritonitis, and hypovolemic shock. When this occurs, it is termed volvulus. According to some sources, this is a true surgical emergency.

Many of these neonates are diagnosed in the first week of life when the neonate presents with bilious vomiting, a tender and distended abdomen, and increasing hemodynamic instability. The surgical procedure relieves the obstruction by reducing the volvulus, dividing the fixation bands between the cecum and the duodenum or jejunum, and widening the base of the mesentery.

a) The major concerns in anesthetic management are airway management, fluid and electrolyte replacement, treatment of sepsis, and postoperative pain management.

b) Any baby with intestinal obstruction will likely have abdominal distention, which could impede diaphragmatic movement, and is at higher risk for aspiration of gastric or intestinal contents.

c) This necessitates the use of a rapid-sequence induction with the proper application of cricoid pressure.

d) If there is concern for a difficult airway, then awake intubation should be considered.

e) There is likely volume depletion caused by peritonitis, ileus, bowel manipulation, and sepsis. It is absolutely necessary to have adequate IV access, and it is desirable to have a central line and an arterial line.

f) The choice of anesthetic agents should depend on the neonate’s condition. It is not advisable to use nitrous oxide, but other inhalation agents are acceptable.

g) As with other emergent abdominal procedures, postoperative mechanical ventilation may be required, making the intraoperative choice of an opioid and nondepolarizing muscle relaxant a good choice.

h) Although anesthetic agent choice is not critical, the maintenance of an adequate circulating volume and red blood cells is vital to ensure perfusion of vital organs.

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an intestinal inflammation that can become a life-threatening emergency situation. It occurs primarily in preterm babies with a gestational age of less than 32 weeks and with a weight of less than 1500 g. The etiology of the problem is reported to be secondary to bowel ischemia and immaturity, probable bacterial invasion, and premature oral feeding.

a) Diagnosis is confirmed by abdominal radiography that shows fixed dilated intestinal loops, pneumatosis intestinalis, portal vein air, ascites, and pneumoperitoneum.

b) Accompanying laboratory values might show evidence of hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, metabolic acidosis, hyperglycemia, or hypoglycemia and, in the most serious cases, signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation.

c) The common symptoms of NEC are listed in the following box.

d) When an attempt at medical management is unsuccessful, surgical intervention consists of an exploratory laparotomy with resection of dead bowel, usually a colostomy, and peritoneal lavage.

a) These neonates are very sick and usually come to the operating room already intubated and with ventilator support.

b) If they are not intubated, a rapid-sequence induction or awake intubation is indicated.

c) The anesthetic drugs chosen should depend on the patient’s condition, but a common choice is a narcotic and relaxant technique. These are thought to be the safest choice in the presence of cardiovascular instability because the inhalation agents may further depress the myocardium and lower the blood pressure to unacceptable levels.

d) Nitrous oxide is avoided, and compressed air can be added to the gas mixture if there is concern over high oxygen concentrations.

e) If cardiac output is low and renal perfusion is below normal, dopamine may be indicated.

f) The amount of third space loss in these patients is very large and may require multiple blood volumes of crystalloid and colloid combinations to replace intravascular volume. Red blood cells, fresh-frozen plasma, and platelets also may be required to increase oxygen-carrying capacity or to treat factor deficiency.

g) The postoperative care should focus on continuation of the fluid resuscitation and cardiorespiratory support and mechanical ventilation until the baby stabilizes.

Imperforate anus

During the first few days after birth, when there is no passage of meconium, the diagnosis of imperforate anus is considered. The degree of this anomaly can range from a mild stenosis to complete anal atresia that is associated with other anomalies. The VACTERL association (vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiac defects, TEF, renal abnormalities, and limb malformations) contains all of the above-mentioned anomalies.

a) In male newborns, the operative procedure may be urgent to allow the passage of meconium via a colostomy.

b) In female newborns, because of the usual presence of a rectovaginal fistula, the procedure can be delayed for a few weeks.

c) The anesthetic considerations for the neonate are based on the existence of associated anomalies and fluid and electrolyte balance.

Other intestinal obstructive lesions

Duodenal obstruction, jejunoileal atresia, and meconium ileus can all result in a complete intestinal obstruction. Although each of these pathologies is different in etiology and presentation, the anesthetic management is very similar to that for the previously mentioned midgut volvulus.

Neurosurgical procedures

Neonatal hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is usually the result of some existing pathologic process. It is usually caused by an obstruction in the CSF system or an inability to absorb CSF. The standard treatment is the placement of a shunting catheter from the ventricle of the brain to another location to allow absorption of the fluid. Most often the shunt is placed from the cerebral ventricle to the peritoneal cavity. Occasionally, the catheter will be placed in the right atrium or pleural cavity. In newborns and neonates, if the hydrocephalus develops slowly, the cranial vault will expand to accommodate the increase in brain bulk. When there is no more ability to expand, ICP begins to increase, and the baby will start to exhibit signs and symptoms of increased ICP.

The signs and symptoms of increasing ICP are a tense anterior fontanel, irritability, somnolence, or vomiting.

a) Anesthetic management is directed at controlling the ICP and relieving the obstruction.

b) The urgency of the procedure will be determined by the preanesthetic assessment of the ICP.

c) The major risk associated with delay is the possible herniation of the brain caused by increasing pressure in the cranial vault.

d) Comorbidities such as prematurity and all associated problems must be addressed.

e) Induction in the presence of increased ICP is usually a rapid-sequence induction and tracheal intubation.

f) A variety of anesthetic agents are acceptable for maintenance with the goal being to extubate the patient at the end of the procedure.

g) If the neonate is preterm, it is advisable to adjust the oxygen concentration to maintain oxygen saturation at 95% to 97%. This decreases the risk of retinopathy of prematurity.

h) The neurologic status of the neonate could affect the decision to extubate immediately, and mechanical ventilation could be required.

Myelomeningocele

Myelomeningocele is the most common CNS defect that occurs during the first month of gestation. Another common name for this defect is spina bifida. It is failure of the neural tube to close, resulting in herniation of the spinal cord and meninges through a defect in the spinal column and back. If the herniation only contains meninges, it is a meningocele. If the herniation contains meninges and neural elements, it is a myelomeningocele. These lesions mostly occur in the lumbosacral region but can occur at any level of the neuraxis. The repair of the defect is considered urgent and is usually undertaken within the first 24 hours of life to avoid the increasing risk of bacterial contamination of the spinal cord and further deterioration of neural and motor function.

a) Most newborns with myelomeningocele do not have other associated anomalies or congenital heart disease.

b) These neonates, however, often have an Arnold-Chiari malformation. The Arnold-Chiari malformation is a result of the hindbrain being displaced downward into the foramen magnum, resulting in hydrocephalus.

c) This will necessitate the placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, usually during the myelomeningocele repair.

d) There are usually significant neurologic deficits below the level of the lesion, and evaluation of the degree of deficit is important to anesthetic decision making.

a) Preoperative assessment should include a thorough review of all other organ systems to rule out additional congenital anomalies.

b) Minimal laboratory work should include a complete blood count and a type and screen for blood.

c) Routine neonatal monitoring is necessary, and the use of invasive monitoring techniques should be based on a risk-to-benefit analysis.

d) Positioning and airway management are the biggest challenges for the anesthesia provider.

e) Most of these babies can be induced and intubated in the supine position with the lumbosacral defect supported in a “donut” ring or with strategically placed towels to avoid direct pressure on the dural sac.

f) If the defect is very large or if there is accompanying severe hydrocephalus, it may be necessary to place the neonate in the lateral position for induction and intubation.

g) If there is a suspicion of a difficult airway, the ETT may be placed with the patient awake after administration of atropine and preoxygenation.

h) Adequate IV access is essential because of the possibility of significant blood loss during the procedure.

i) If the defect is large, the surgeon may be required to débride a large amount of tissue for closure, resulting in a large blood loss.

j) Anesthesia can be induced with an inhalation or IV technique.

k) After the ETT is placed, the procedure is performed in the prone position with appropriate protection of all body parts.

l) In some institutions, the use of muscle relaxants is discouraged to allow for neurophysiologic monitoring.

m) Anesthesia can be maintained with a variety of drugs, keeping in mind the goal of extubation at the end of the procedure and the possibility of postoperative apnea.

n) These patients are prone to hypothermia, and conservation of body heat should include warming the operating room to at least 80°F before the procedure and until the baby is draped.

o) Radiant heat lamps should be used during the preparation and positioning of the patient. A forced-air warmer should also be placed underneath the neonate to maintain body temperature.

p) Anesthetic gases should be humidified to prevent heat loss and minimize pulmonary complications.

q) An increased sensitivity to latex has been reported in these babies. As a precaution, they should be treated as latex allergic, avoiding all products that contain latex.