Gastrointestinal system

A Carcinoid tumors and carcinoid syndrome

Definition

Carcinoid tumors consist of slow-growing malignancies composed of enterochromaffin cells usually found in the gastrointestinal tract. They may also occur in the lung, pancreas, thymus, and liver. Carcinoid tumors have a low incidence rate of 1.9 per 100,000.

Pathophysiology

Speculation is that the advent and increasing use of proton pump inhibitors is a major contributory factor to the development of carcinoid tumors. A delay of several years frequently occurs before a diagnosis of carcinoid tumor is made. The gastrointestinal tract accounts for about two-thirds of carcinoids. Within the gastrointestinal tract, most tumors occur in the small intestine (41.8%), rectum (27.4%), and stomach (8.7%). Distant metastases may be evident at the time of diagnosis in 12.9% of patients, but better diagnostic techniques have contributed to improved survival rates.

The tumors can secrete several biologically active substances, including serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), kallikrein, histamine, prostaglandins, adrenocorticotropic hormone, gastrin, calcitonin, and growth hormone, among others. Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with carcinoid tumors develop carcinoid syndrome.

Clinical manifestations

The manifestations of carcinoid syndrome are in the table on pg. 100 and as follows:

• Episodic cutaneous flushing (kinins, histamine)

• Diarrhea (serotonin, prostaglandins E and F)

• Tricuspid regurgitation, pulmonic stenosis

• Supraventricular tachydysrhythmias (serotonin)

• Bronchoconstriction (serotonin, bradykinin, substance P)

• Hypotension (kinins, histamine)

• Abdominal pain (small bowel obstruction)

• Hypoalbuminemia (pellagra-like skin lesions resulting from niacin deficiency)

Vasoactive peptides released from carcinoid tumors located in the bronchi and ovaries exert a faster effect because of their direct drainage into the portal vein. Carcinoid tumors are also functionally autonomous. Two factors that enhance release of carcinoid hormones are direct physical manipulation of the tumor and β-adrenergic stimulation.

Principal Mediators of Carcinoid Syndrome and Their Clinical Manifestations

| Mediator | Clinical Manifestations |

| Serotonin | Vasoconstriction (coronary artery spasm, hypertension), increased intestinal tone water and electrolyte imbalance (diarrhea), tryptophan deficiency (hypoproteinemia, pellagra) |

| Kallikrein | Vasodilation (hypotension, flushing), bronchoconstriction |

| Histamine | Vasodilation (hypotension, flushing), arrhythmias, bronchoconstriction |

Treatment

Patients with carcinoid syndrome may undergo primary resection of the carcinoid tumor. Examples of other procedures that these patients often undergo include cardiac valve replacement and hepatic resection (e.g., lobectomy) for excision of metastases.

Anesthetic considerations

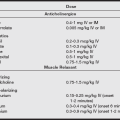

Many anesthetic techniques have been used successfully in the treatment of patients with carcinoid syndrome (see the following section). Preoperative preparation of the patient requires correction of deficiencies in circulating volume and electrolyte levels. Use of histamine-releasing agents, such as morphine, and atracurium should be avoided. Fasciculations may induce release of carcinoid hormones and are therefore prevented by avoidance of succinylcholine, although it has been used successfully many times, especially for rapid sequence induction.

Anesthetic considerations in carcinoid syndrome

• The most common clinical signs are flushing, wheezing, blood pressure and heart rate changes, and diarrhea.

• Preoperative assessment should include complete blood count, measurement of electrolytes, liver function tests, measurement of blood glucose, electrocardiogram (echocardiogram if indicated), and determination of urine 5-HIAA levels.

• Optimize fluid and electrolyte status and pretreat with octreotide as noted. Continue octreotide throughout the postoperative period. Interferon-α has shown success in controlling some symptoms.

• Both histamine-1 and -2 receptor blockers must be used to fully counteract histamine effects.

• Avoid histamine-releasing agents such as morphine, thiopental, and atracurium.

• Avoid sympathomimetic agents such as ketamine and ephedrine.

• Treat hypotension with an α-receptor agonist such as phenylephrine.

• General anesthesia is preferred over regional anesthesia. Patients with high serotonin levels may exhibit prolonged recovery; therefore, desflurane and sevoflurane, which have rapid recovery profiles, may be beneficial.

• Aggressively maintain normothermia to avoid catecholamine-induced vasoactive mediator release.

• Monitor intraoperative plasma glucose because these patients are prone to hyperglycemia. Treat with insulin as is customary.

Octreotide, a somatostatin analog, is used to blunt the vasoactive and bronchoconstrictive effects of carcinoid tumor products. Octreotide mimics the inhibitory action of somatostatin on the release of several gastrointestinal hormones, as well as those derived from carcinoid tumors. Treatment for 2 weeks preoperatively with a dose of 100 mcg subcutaneously three times a day is standard. If prior therapy was not used, a dose of 50 to 150 mcg subcutaneously is given preoperatively. Intraoperative infusion may be continued at 100 mcg/hr. Bolus doses of 100 to 200 mcg given intravenously may be used for intraoperative carcinoid crises. Lantrotide (which is administered every two weeks) and octreotide LAR (which can be given monthly) are long-acting formulations that are superior in terms of patient acceptance and cost effectiveness.

Patients with hypotension should be treated with an α-adrenergic agonist (e.g., phenylephrine infusion) to avoid hormone release by β-adrenergic stimulation. Bronchospasm resulting from histamine or bradykinin release has been shown to be resistant to ketamine and inhalation anesthetics. Low-dose β2-agonists are effective in bronchodilation and have relatively little influence on carcinoid hormone release. In the presence of high levels of serotonin in carcinoid syndrome, adjustments in anesthetic selection and dosage must be considered if further compromise of cardiovascular function is to be prevented.

B Gallstones and gallbladder disease

Definition

Obstruction of the cystic duct by gallstones results in acute, severe midepigastric pain, typically radiating to the right abdomen. Inspiratory effort usually accentuates the pain (Murphy’s sign).

Clinical manifestations

Increases in plasma bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and amylase levels frequently occur. Ileus and localized tenderness may indicate perforation with peritonitis. Leukocytosis and fever are often present. The presence of jaundice indicates complete obstruction of the cystic duct. Symptoms are frequently confused with those of myocardial infarction. Differential diagnosis is accomplished through serial electrocardiogram (ECG) evaluations and laboratory analysis of serum enzymes that are specific to cardiac muscle. Cholescintigraphy (a contrast study that evaluates gallbladder excretion of a radiographically labeled substance) and ultrasonography are often used for clinical confirmation of the diagnosis.

Anesthetic considerations

Patients with symptoms indicative of acute cholecystitis are often volume depleted as a result of intolerance of oral intake, vomiting, and possible preoperative nasogastric evacuation of gastric contents. Dehydration warrants preoperative intravenous fluid replacement. Gastric suction may be warranted in the presence of ileus. The presence of free abdominal air, as determined by abdominal radiography or symptoms of an acute abdomen (fever, ileus, rigid and painful abdomen, vomiting, dehydration), suggests the presence of a ruptured viscus, possibly including perforation of the gallbladder. Under these circumstances, emergency exploratory laparotomy is undertaken.

Cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis

Acute obstruction of the common bile duct often produces symptoms similar to those seen in patients with cholecystitis. Recurrent bouts of acute cholecystitis induce the development of fibrotic changes in gallbladder structure, thereby impeding the ability of the gallbladder to adequately expel bile. The presence of Charcot’s triad (fever and chills, jaundice, upper quadrant pain) aids in establishing the differential diagnosis in acute ductal obstruction. Weight loss, anorexia, and fatigue complete the symptomatology. Diagnostic modalities include radiography, transhepatic cholangiography, ultrasonography, cholescintigraphy, and computed tomography (CT) scan. A dilated common bile duct and biliary tree are typically observed in these studies.

C Hiatal hernia and gastric reflux

Definitions

Hiatal hernia

A hiatal hernia consists of a defect in the diaphragm that allows a portion of the stomach to migrate upward into the thoracic cavity. Two types of esophageal hiatal hernias are the sliding type (type I), which is formed by the movement of the upper stomach through an enlarged hiatus, and the paraesophageal type (type II), in which the esophagogastric junction remains in normal position but all or part of the stomach moves into the thorax and assumes a paraesophageal position. A third type of hiatal hernia (type III) has been identified that combines the features of a sliding and a paraesophageal hernia. A fourth type of hiatal hernia (type IV) occurs when other organs, such as the colon or small bowel, are contained in the hernia sac that is formed by a large paraesophageal hernia. Hiatal hernia and peptic esophagitis often exist concurrently, although one does not cause the other.

Gastric reflux

Gastric reflux relates to a reduced lower esophageal sphincter tone, which can increase the risk for regurgitation and aspiration. Reflux can occur without the presence of hiatal hernia. The lower sphincter is a physiologic sphincter with no specialized musculature. Tone is 15 to 35 mmHg.

Incidence and prevalence

Types I to IV hiatal hernias are present in 10% of the population, usually without symptoms. Only 5% of the population has reflux symptoms along with a hiatal hernia.

Pathophysiology

In most cases, the cause is unknown, whether the condition is congenital, traumatic, or iatrogenic.

Clinical manifestations

The major symptom is retrosternal pain of a burning quality that commonly occurs after meals. It is assumed that patients with a hiatal hernia are predisposed to developing peptic esophagitis, thereby providing a rationale for surgical correction of this condition. Most patients with hiatal hernia do not have symptoms of reflux esophagitis, however, and do not require H2-agonist and oral antacid therapy. Nevertheless, implementation of aspiration precautions on induction of general anesthesia and emergence is still strongly recommended.

Treatment

The primary goal in the surgical correction of hiatal hernia consists of reestablishment of gastroesophageal competence. This usually entails repair of the sliding hernia, reduction by 2 cm or more of the tubular distal esophagus below the diaphragm, and valvuloplasty. An abdominal, thoracic, or thoracoabdominal surgical approach may be selected. Common procedures for correction of hiatal hernia include the Nissen, Belsey, and Hill operations. Laparoscopically assisted fundoplication techniques are also more commonly being used. A gastroplasty may be performed (the Collis procedure) in association with repair of the hiatal hernia when indicated, usually in patients with a shortened esophagus. If a thoracic approach is selected, the patient must be assessed for ability to tolerate one-lung anesthesia.

Anesthetic considerations

Symptomatic patients require pretreatment with a nonparticulate antacid and an H2-blocker. For induction of anesthesia, elevation of the head of the bed or stretcher and rapid-sequence induction to prevent aspiration should be considered. If the hernia is large, one-lung anesthesia may be used to improve surgical access during repair. Communication with the surgical team is imperative when the thoracoabdominal approach is being considered.

D Inflammatory bowel disease

Definition

In the United States, between 200,000 and 300,000 individuals have inflammatory bowel disease, and approximately 30,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. The two major types of inflammatory bowel disease are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory disease, primarily of the mucosa of the rectum and distal colon. It is a chronic disease that is fraught with remissions and exacerbations.

Incidence and prevalence

Ulcerative colitis affects female patients more frequently than male patients and has a bimodal age distribution that shows a first peak incidence between ages 15 and 20 years and a second, smaller, peak between ages 55 and 60 years. The disorder is speculated to have a strong familial genetic predisposition, but psychological factors have also been implicated in its cause. Crohn’s disease most commonly occurs at about 30 years of age.

Pathophysiology

Crohn’s disease involves primarily the distal ileum and large colon in approximately 50% of patients. The remainder of patients experience disease that is localized to either the colon or portions of the small intestine (regional enteritis). The deeper layers of the intestinal mucosa are typically involved, a situation that leads to derangements in colonic absorption.

Clinical manifestations

Owing to the loss of functional absorptive surfaces in the large colon, patients with Crohn’s disease are often deficient in magnesium, phosphorus, zinc, and potassium. They also have deficiencies secondary to the loss of absorptive capability in portions of the small intestine. Protein-losing enteropathy is often encountered, as is anemia resulting from occult blood loss and deficiencies in vitamin B12 and folic acid. Iron deficiency secondary to insufficient intestinal absorption also contributes to development of an anemic state. Involvement of the distal ileum in the disease process results in deficiencies in vitamin B12 and in nutrients that are dependent on bile acids for absorption. Disturbance in the enterohepatic circulation of bile in the terminal ileum is reflected in complex nutrient deficiencies, including proteins, zinc, magnesium, phosphorus, fat-soluble vitamins, and vitamin B12. This state is typical of patients with chronic Crohn’s disease. Folate deficiency may also be present in patients with Crohn’s disease who receive sulfasalazine preparations.

Fistulas often develop between inflamed portions of the intestine and adjacent abdominal structures. Abdominal and pelvic abscesses, rectocutaneous fistulas, and perirectal abscesses have a high incidence in these patients. Increased calcium oxalate absorption in the terminal ileum frequently occurs, resulting in a high rate of renal calculi and cholelithiasis.

Treatment

Medical therapy for Crohn’s disease includes a variety of drugs and is given in the box below.

Surgery is warranted when medical treatment fails or when complications supervene. Although effective in the relief of complications, surgical resection of the diseased colon and ileum does not alter the progression of the disease. The primary principle of surgical management is to limit the operation to the correction of the presenting complication, which could include bowel obstruction, fistulas, abscesses, and symptoms that indicate widespread symptomatic disease (for which total colectomy and ileal resection may be warranted).

Most patients with Crohn’s disease undergo surgery, and a large number require repeat or continued procedures. The recurrence rate at 10 years after surgery is 50%. A high likelihood of repeat surgery involves areas of the remaining bowel proximal to the area of a previous anastomosis. Patients with a history of Crohn’s disease are also shown to have a higher prevalence of bowel carcinoma.

Ulcerative colitis

Symptoms usually include abdominal pain, fever, and bloody diarrhea. Ulcerative colitis is typically chronic, with relatively low-grade symptoms, such as bloody stools, malaise, diarrhea, and pain. In approximately 15% of patients, however, ulcerative colitis that has acute, fulminating characteristics may occur. Under this circumstance, severe abdominal pain, profuse rectal hemorrhage, and high fever are seen. Associated symptoms include nausea and vomiting, anorexia, and profound weakness. Physical signs usually include pallor and weight loss.

Associated with an acute onset of fulminating ulcerative colitis is toxic megacolon, which is characterized by severe colonic distention that causes shock. In patients with this condition, the distended bowel lumen provides an environment that is conducive to bacterial overgrowth. This condition, coupled with erosive intestinal inflammation and perforation, allows for the systemic release of bacteria-produced toxins. Clinical signs and symptoms of toxic megacolon include fever, tachycardia, abdominal distention, pain, ileus, and dehydration. Electrolyte derangements, anemia, and hypoalbuminemia are also commonly present.

An increased incidence of large joint arthritis is seen in patients when the disease is clinically active. Concomitant liver disease, as evidenced by fatty infiltrates and pericholangitis, may also complicate the clinical picture. Other extracolonic manifestations of ulcerative colitis include iritis, erythema nodosum, and ankylosing spondylitis.

Treatment

Therapy for ulcerative colitis is initially medical. As with Crohn’s disease, sulfasalazine preparations, antidiarrheal agents, and corticosteroids are the cornerstones of medical therapy. Both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis result in systemic disorders, such as anemia and nutritional deficiencies, which are handled in the same supportive manner. In both diseases, surgical resection is reserved for patients with intractable complications. Whereas surgery for Crohn’s disease is nondefinitive and complication oriented, proctocolectomy with ileostomy is generally curative for ulcerative colitis.

Anesthetic considerations

Anesthetic management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease begins with a thorough, systematic patient history, and particular attention is paid to the patient’s fluid and electrolyte status. Possible extracolonic complications (e.g., sepsis, liver disease, anemia, arthritis, hypoalbuminemia, and other metabolic derangements) must also be considered during planning and perioperative management. Efforts to optimize the medical condition of such patients before elective surgery are strongly recommended.

Prophylactic steroid coverage is likely to be indicated, particularly in patients receiving long-term steroid therapy. Inclusion of nitrous oxide in anesthesia delivery should be reconsidered with the possibility of bowel distention associated with its prolonged intraoperative use. Awareness of complications from parenteral nutritional therapy (e.g., hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia, increased carbon dioxide production, renal or hepatic dysfunction, nonketotic hyperosmolar hyperglycemic coma, and hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis) is also necessary for patients receiving total or partial parenteral nutritional support. Administration of a preexistent parenteral nutritional support infusion should be maintained throughout the perioperative period at the ordered infusion rate. Periodic laboratory assessment of metabolic status (i.e., serum glucose and electrolytes) should be performed and guide corrective interventions for detected derangements. The severity of extracolonic influence on the function of other organ systems dictates appropriate technique and drug selection, as well as the extent to which invasive monitoring is used. Correction of fluid, electrolyte, and hematologic derangements may be necessary before surgery. Increased intraluminal pressure caused by the administration of anticholinesterases for reversal of neuromuscular blockade has been shown to have no effect on colonic suture lines. No particular anesthetic technique is mandated; however, the use of a combined technique (epidural and general anesthesia) is attractive for both intraoperative use and postoperative analgesia needs.

E Pancreatitis

Pathophysiology

The cause of pancreatitis is multifactorial. Common causes include alcohol abuse, direct or indirect trauma to the pancreas, ulcerative penetration from adjacent structures (e.g., the duodenum), infectious processes, biliary tract disease, metabolic disorders (e.g., hyperlipidemia and hypercalcemia), and certain drugs (e.g., corticosteroids, furosemide, estrogens, and thiazide diuretics). Patients who have undergone extensive surgery involving mobilization of the abdominal viscera are at risk for development of postoperative pancreatitis, as are patients who have undergone procedures involving cardiopulmonary bypass.

Clinical manifestations

Acute pancreatitis is characterized as a severe chemical burn of the peritoneal cavity. Enzymes implicated as major culprits in the syndrome of pancreatitis are those activated by trypsin, enterokinase, and bile acids. Cardiovascular complications of acute pancreatitis can lead to pericardial effusions, alterations in cardiac rhythmicity, and signs and symptoms mimicking acute myocardial infarction, thrombophlebitis, and cardiac depression. Acute pancreatitis also predisposes patients to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

Pain is the foremost symptom of acute pancreatitis and may be variable in quality (i.e., localized or radiating, dull and tolerable, or severe and unremitting). Pancreatic pain may radiate from the midepigastric to the periumbilical region and may be more intense when the patient is in the supine position.

Abdominal distention is often seen and is largely attributable to the accumulation of intraperitoneal fluid and paralytic ileus. Nausea and vomiting and fever are common symptoms. Hypotension is seen in 40% to 50% of patients and is attributable to hypovolemia secondary to the loss of plasma proteins into the retroperitoneal space. Acute renal failure secondary to dehydration and hypotension may occur.

Hypocalcemia frequently develops in patients with acute pancreatitis, and this condition obviates monitoring the ECG for cardiac rhythm disorders (e.g., lengthened QT interval with possible reentry dysrhythmias). The clinician must also be observant for signs of tetany. Clinical shock may develop that is largely secondary to the effects of vasoactive kinin peptides (e.g., bradykinin) released during the inflammatory process; these peptides enhance vasodilation, vascular permeability, and leukocyte migration.

Elevated serum amylase levels are often present but do not necessarily indicate primary pancreatic disease; other intraabdominal disease processes result in such elevations, including biliary tract disease, tubo-ovarian disease, peptic ulcer disease, and acute bowel disease, including obstruction, inflammation, and ischemia. Elevated serum lipase levels may also be observed. Compressive obstruction of the common bile duct by an edematous head of the pancreas contributes to elevations in serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels.

Radiographic and ultrasonographic findings aid in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic disease. Evidence of free intraperitoneal air by radiography suggests the presence of a perforated viscus. CT is highly effective in the diagnosis of an enlarged, edematous pancreatic head, which is typically seen in patients with pancreatitis.

Treatment

Supportive therapy is initially undertaken in acute pancreatitis. This regimen usually includes intensive care unit admission and may involve implementation of invasive monitoring, fluid and hemodynamic resuscitation, and interventions necessary for the preservation of perfusion and function of the abdominal viscera. Severely ill, malnourished patients are often given parenteral nutritional support.

If the cause of pancreatitis is obstructive biliary disease caused by the presence of a stone in the common bile duct or by inflammation of the gallbladder, cholecystectomy and possibly common bile duct exploration are indicated.

Anesthetic considerations

The choice of anesthetic technique and the extent to which monitoring modalities are used are based on an assessment of the patient’s history, the acuity of disease, and the degree of preexisting physical compensation. Special attention is directed toward the correction of significant intravascular volume deficits. The presence of labile hemodynamics and alterations in hepatic function must also be discerned, and appropriate accommodating modifications must be made to the anesthetic plan, for example, ensuring stable arterial pressure, using anesthetic agents and adjuvants that require minimal hepatic biotransformation, ensuring adequate oxygenation, and replacing electrolytes and blood volume.

Chronic pancreatitis

Chronic alcoholism is a common etiologic factor in chronic pancreatitis. This condition is strongly suggested by the classic diagnostic triad of stea-torrhea, pancreatic calcification (evidenced radiographically), and diabetes mellitus. Individuals with chronic pancreatitis are often malnourished and emaciated. They are more often male than female. Other conditions besides chronic alcohol abuse that are associated with the development of chronic pancreatitis include significant and usually chronic biliary tract disease and the effects of pancreatic injury sustained at an earlier age.

Formation of a pseudocyst occurs in up to 8% of alcoholic patients after resolution of a bout of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatic abscess occurs in 3% to 5% of patients with acute pancreatitis but is present in 90% of patients dying as a result of acute pancreatitis.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical picture may also include hepatic disease, as evidenced by jaundice, ascites, esophageal varices, derangements in coagulation factors, serum albumin, and transferase enzymes. Perturbation in pancreatic exocrine function with consequent enzymatic insufficiency results in malabsorption of fats and proteins in the intestine. Patients with chronic pancreatitis also have a predisposition for the development of pericardial and pleural effusions.

Pancreatic abscesses develop from infected peripancreatic collections of fluid. Abscesses are usually secondary manifestations of chronic pancreatitis and warrant surgical drainage to prevent spread of the infectious contents to the subphrenic and pericolic spaces. Fistula formation is possible, particularly into the transverse colon. Severe intraabdominal hemorrhage is also possible as a result of erosion into major proximal arteries.

Treatment

Surgical drainage of a pancreatic pseudocyst is usually undertaken after a period of maturation of the cyst (usually 6 weeks). The procedure consists of formation of a cystogastrostomy, cystojejunostomy, cystoduodenostomy, or possibly distal pancreatectomy. The location of the pseudocyst dictates the extent and type of procedure used for the provision of drainage of cystic contents into the gastrointestinal tract. Percutaneous external drainage, guided by CT, is reserved for cases in which the pseudocyst is particularly friable. Spontaneous resolution of pseudocysts may be expected in 20% or more of patients who have undergone surgical drainage.

Anesthetic considerations

The patient undergoing surgical treatment of pancreatic disease exhibits a variable clinical picture: the patient may be jaundiced and stable with a painless pancreatic mass or may be severely ill with multiorgan system involvement. Patients may have severe, acute abdominal pain with possible intestinal obstruction or ileus. Aspiration precautions should be in effect during induction of anesthesia and emergence from anesthesia. Perioperative assessment of serum glucose level and institution of appropriate control measures are warranted because these patients are likely to have diabetes (secondary to β-cell dysfunction) or hypoglycemia (as in the case of insulinoma). Derangements in fluid and electrolyte balance must also be anticipated. Rigorous blood product and crystalloid resuscitation may be necessary throughout the perioperative period and likely will necessitate the placement of invasive hemodynamic lines in order to guide therapy and to monitor central pressures.

Potential electrolyte disorders include hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, and possibly hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. The serum hematocrit value may be falsely increased secondary to hemoconcentration, or it may be decreased secondary to the presence of a bleeding diathesis. Coagulation parameters, including platelet count, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen level, should be assessed at regular intervals perioperatively. Preservation of renal function mandates the preoperative assessment of blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and 24-hour creatinine clearance (if possible); urinalysis should also be performed. Intraoperatively a urine output of at least 0.5 to 1 mL/kg/hr should be maintained.

A significant incidence of postoperative respiratory morbidity associated with upper abdominal surgery, as well as the possible preexisting debilitated state of the patient, mandates a thorough assessment of preexisting pulmonary status. This assessment includes arterial blood gas analysis; chest radiography; and, when appropriate, pulmonary function tests. The pulmonary assessment assumes added importance because of the high incidence of pleural effusion secondary to pancreatic disease and secondary to the potential history of heavy tobacco use.

Cardiovascular assessment should assimilate related findings from the assessment of other organ systems so that the degree to which functional hemodynamic impairment may need to be corrected is fully appreciated. Correction of preexisting hemodynamic disturbances entails restitution of plasma volume and the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. Ischemic changes noted on the ECG must be treated promptly. ECG changes mimicking myocardial ischemia are often seen in pancreatitis.

General endotracheal anesthesia is the technique of choice. Preoperative placement of an epidural catheter allows greater flexibility in the intraoperative management of pain and in the provision of postoperative pain control. Patients undergoing extensive pancreatic surgery often require postoperative ventilatory support and intensive care unit monitoring because of the magnitude and the length of the procedure, as well as their preexisting cardiopulmonary status.

Laboratory results should be reviewed, and the patient should be evaluated for shock, hemorrhage, and pain relief (meperidine is the drug of choice). Fluid and electrolyte status is of concern because the patient should receive nothing by mouth. The patient will have a nasogastric tube, and H2 blockers will be given. In addition, the patient should undergo typing and crossmatching for possible transfusion. Plasma expanders, crystalloids, and invasive monitoring may be used.

F Splenic disorders

Definition

A palpable spleen is the major physical sign produced by diseases affecting the spleen and suggests enlargement of the organ. The normal spleen is said to weigh less than 250 g, decreases in size with age, normally lies entirely within the rib cage, has a maximum cephalocaudal diameter of 13 cm by ultrasonography or maximum length of 12 cm or width of 7 cm by radionuclide scan, and is usually not palpable.

Incidence and prevalence

A palpable spleen was found in 3% of 2200 asymptomatic male freshman college students. Follow-up at 3 years revealed that 30% of those students still had a palpable spleen without any increase in disease prevalence. Ten-year follow-up found no evidence for lymphoid malignancies. Furthermore, in some tropical countries (e.g., New Guinea), the incidence of splenomegaly may reach 60%. Thus, the presence of a palpable spleen does not always equate with the presence of disease.

Pathophysiology

Hyperplasia or hypertrophy is related to a particular splenic function such as reticuloendothelial hyperplasia (work hypertrophy) in diseases such as hereditary spherocytosis or thalassemia syndromes that require removal of large numbers of defective red blood cells and to immune hyperplasia in response to systemic infection (infectious mononucleosis, subacute bacterial endocarditis) or to immunologic diseases (immune thrombocytopenia, systemic lupus erythematosus, Felty’s syndrome). Passive congestion results from decreased blood flow from the spleen in conditions that produce portal hypertension (cirrhosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, congestive heart failure). Infiltrative diseases of the spleen include lymphomas, metastatic cancer, amyloidosis, Gaucher’s disease, and myeloproliferative disorders with extramedullary hematopoiesis.

The differential diagnostic possibilities are fewer when the spleen is “massively enlarged,” that is, it is palpable more than 8 cm below the left costal margin or its drained weight is 1000 g or more. Most such patients have non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hairy cell leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia, or polycythemia vera.

Laboratory results

The major laboratory abnormalities accompanying splenomegaly are determined by the underlying systemic illness. A complete blood count is the diagnostic examination needed with any patient presenting with splenic disorders. It is vital for a differential diagnosis. A complete blood count also identifies platelet or white blood cell dysfunction.

Clinical manifestations

The most common symptoms produced by diseases involving the spleen are pain and a heavy sensation in the left upper quadrant. Massive splenomegaly may cause early satiety. Pain may result from acute swelling of the spleen with stretching of the capsule, infarction, or inflammation of the capsule. Symptoms of hypersplenism include fatigue, malaise, recurrent infection, and easy or prolonged bleeding. These symptoms occur from a hyperfunctional spleen that removes and destroys normal blood cells. In portal hypertension, transmitted backpressure results in hypersplenism, which leads to congestive failure of splenic function.

Vascular occlusion with infarction and pain is commonly seen in children with sickle cell crises. Rupture of the spleen, either from trauma or infiltrative disease that breaks the capsule, may result in intraperitoneal bleeding, shock, and death. The rupture itself may be painless.

Treatment

Correction or amelioration of certain hematologic and immunologic disorders may be attempted through splenectomy. Commonly accepted medical disease processes for which splenectomy is considered include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, Hodgkin’s disease, lymphoma, certain leukemias, hereditary spherocytosis, hereditary hemolytic anemia, idiopathic autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and hypersplenism. Splenectomy may also be performed in the treatment of patients with thalassemia and sickle cell disease when these diseases are refractory to medical management and when hypersplenism supervenes. The development of primary (with no identifiable underlying cause) or secondary (from a known cause) hypersplenism may warrant splenectomy. Treatment of the primary disease process usually provides relief of symptoms. Splenectomy, however, is often a necessary part of therapy, particularly in long-standing disorders.