Hematologic system

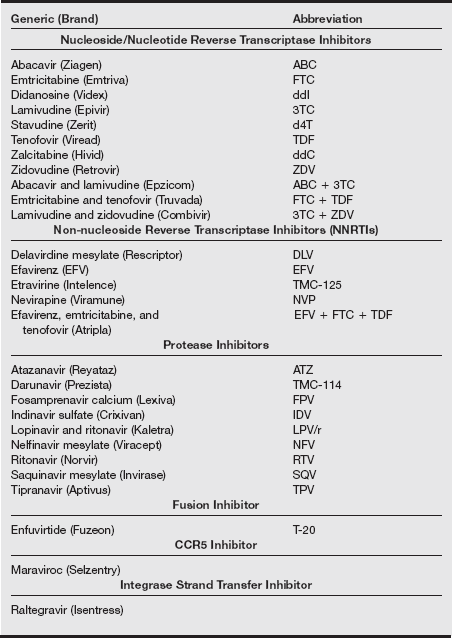

A AIDS/HIV infection

Definition

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the most significant etiology of secondary immunosuppression that can result from infection that causes depletion of immune cells. The virus exists as two main types, HIV-1 and HIV-2. Of the two, HIV-1 is more prevalent and more pathogenic. The primary targets of HIV infection are CD4+ lymphocytes. A glycoprotein on the viral envelope binds to the CD4 antigen to allow the virus to enter the T cell. HIV is a retrovirus, that is, its genome contains 2 strands of single-stranded RNA. After the virus enters the host cell, its RNA undergoes reverse transcription to produce complementary DNA that is incorporated into the host cell DNA. Synthesis of new viral RNA then occurs in the host cell followed by formation of new virus particles and their release to infect other CD4+ cells. Infection with HIV alters T-cell function and causes cytotoxicity, leading to the characteristic decline in CD4+ cells. Exactly how HIV infection kills T cells, though, is not known and may involve several mechanisms. Ultimately, with a sufficient fall in CD4+ cells, individuals become susceptible to life-threatening opportunistic infections.

Pathophysiology

The epidemiologic basis for HIV infection begins with transmission of the virus through certain body fluids. Infection with HIV can progress to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and fatal disease. Although more than 25 million individuals have died as a result of AIDS complications since the first description of the disease, early detection, evaluation, and pharmacologic intervention have become very successful in controlling HIV infection in many individuals while preserving immune system integrity.

The potential sources of transmission of HIV are blood contact, sexual transmission, and perinatal exposure (see box below).

Human immunodeficiency virus is transmitted through mucous membranes during anal, vaginal, and oral intercourse. Transmission of HIV also occurs through sharing injection equipment and needles. Vertical transmission occurs from mother to child. Blood, semen, vaginal fluid, breast milk, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), amniotic fluid, and serosanguineous fluid can transmit HIV; saliva, tears, and sweat do not. The virus cannot survive outside the host, and 90% to 99% of infective HIV on dry surfaces is eliminated within hours. Insect bites and casual contact carry no risk.

As epidemic and scientific approaches to HIV infection evolved, the focus shifted from “risk groups” to “risky behaviors.” This distinction is important because risk groups can give a false sense of security by implying that certain groups of individuals are less vulnerable to infection. Risky behaviors is a more useful term, falling along a spectrum of “no risk” (e.g., complete sexual abstinence), “very low risk” (e.g., 100% use of latex condoms), to “very high risk” (e.g., unprotected receptive anal intercourse with ejaculation), with other behaviors in midspectrum. The physician serves as a source of accurate information to be provided in simple, nonjudgmental terms because ultimately the patient will decide the acceptable degree of risk.

Acute infection with HIV is characterized by a mononucleosis-like illness, in which release of inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), causes symptoms such as malaise, fever, myalgias, and rash. At the same time, a transient decline in circulating CD4+ cells occurs. Over several weeks after the primary infection, antibodies directed against virus envelope proteins are produced, and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) begin to kill infected T cells that display HIV peptides. These immune responses permit resolution of the symptoms of acute infection; however, anti-HIV antibodies and CTLs become overwhelmed by viral replication and mutation, and progression of HIV infection occurs.

Spontaneous resolution of the acute symptoms of HIV infection is followed by a variable period of asymptomatic infection. If the infection is not treated, a gradual, progressive fall in CD4+ cells occurs in conjunction with a gradual increase in the plasma viral load. Progression to AIDS in untreated individuals occurs in an average time of 10 years, although in some individuals, progression may occur much more rapidly or perhaps not at all. With respect to the latter possibility, there are reports of individuals who have not developed AIDS despite multiple exposures to HIV, suggesting that the adaptive immune system in some individuals may provide chronic protection by an as yet undefined mechanism. Clinically, AIDS is defined as a CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/μL or by the presence of an AIDS-indicator condition.

About 33 million people worldwide are living with HIV/AIDS in 2007. Of these, 2.7 million have been newly infected, and 2 million people have died of HIV/AIDS. Developing countries account for more than 95% of these infections (UN AIDS, 2007). From 2004 to 2007, there has been an increase of 15% in the incidence of HIV/AIDS cases in the United States. This increase occurred mainly in persons age 40 to 44 years, who accounted for 15% of all HIV/AIDS cases, likely caused by both changes in reporting systems and increased HIV testing.

A disproportionate number of minorities and women are affected by HIV. Blacks constituted 45% of newly diagnosed cases in 2006, with a rate of infection of 83.7 per 100,000. Of these, 60% are women. Blacks living with HIV/AIDS constituted about 60% of the adult HIV-positive population in 2007, with a rate of 76.7 per 100,000. Similarly, Hispanics, although constituting 12% of the population, reflected 17% of persons newly infected with HIV in 2006 and 20% of those living with HIV/AIDS in 2007, with rates of 29.3 and 20 per 100,000, respectively. Year-end prevalence rates in 2007 were 185.1 per 100,000 population, with a range between 2.2 in Samoa and 1750 per 100,000 in the District of Columbia.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome was diagnosed within 12 months of diagnosis of HIV infection for a larger percentage of Hispanics and male intravenous drug users (IVDUs) and men with high-risk heterosexual contact. Survival after AIDS diagnosis has increased in those who were diagnosed between 1998 and 2000, among men who have sex with men, and those who have acquired HIV perinatally. More whites survive 48 months after a diagnosis of AIDS than minorities. Survival has declined in IVDUs and with each year of age at diagnosis after age 35 (HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2007).

The three main modes of transmission of HIV are as follows:

1. Through the mucous membranes during anal, vaginal, or oral sexual intercourse with an HIV-infected person. The average risk of transmission in heterosexual exposure is one in 1000 and increases with commercial sex workers to about five to 10 in 100. Whereas co-infection with other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), rough sex, and higher viral load increase risk, condom use and male circumcision reduce risk. Uncircumcised men a run risk similar to a woman, and circumcised men may transmit the virus to female partners four times as efficiently as uncircumcised men. Postmenopausal women are more susceptible because of thinning of the vaginal mucosa. Risk of infection per act has been suggested from cohort studies, so physicians should avoid discussing risks in numeric terms.

2. Through the veins while sharing needles or injection paraphernalia with an HIV-infected person

3. Vertically from an HIV-infected mother to an infant during pregnancy, delivery, or through breastfeeding. High viral load, prolonged time after rupture of membranes, and chorioamnionitis increase risk of transmission, and peripartum prophylactic antiretroviral therapy decreases risk. The overall risk of transmission by breastfeeding is about 15% to 25% in 18- to 24-month-old infants.

Occupational exposure occurs by needlestick injuries (risk, 3:1000), infected blood or fluid splashing into the mouth or nose, or exposure to infected blood through a cut or an open wound. Mucous membrane exposure carries a risk of infection of about nine in 10,000. Transmission of HIV through infected blood is extremely rare after routine screening of the blood supply was initiated in 1985. With risk of transmission as low as two per million, 16 annual infections are accounted for by infectious donations. Neither insect bites nor casual contact carry any risk.

Human immunodeficiency virus can be transmitted by blood, semen, vaginal fluid, breast milk, and serosanguineous body fluids. Contact with CSF, amniotic fluid, and synovial fluid can be a risk factor for HIV transmission. Importantly, although HIV can be present in small quantities in saliva, sweat and tears, contact with these fluids does not transmit HIV. The virus cannot survive outside the host, and the amount of infective virus dried on surfaces is reduced by 90% to 99% in a few hours.

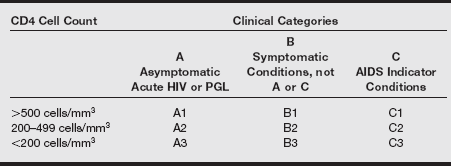

The two classification systems currently in use to monitor the severity of HIV illness and assist with its management have been developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (see table on pg. 115) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (see box below). The CDC classification, last modified in 1993, uses CD4+ counts and specific HIV-related conditions, but the WHO classification, developed in 1990 and revised in 2007, is guided by clinical observations and can be used in settings where access to CD4+ tests is unavailable. The CDC lists AIDS categories as A3, B3, C1, C2, and C3, with 23 AIDS-defining conditions. The WHO includes primary HIV infection and four clinical stages.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Classification System of HIV/AIDS

PGL, Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy.

Data from US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR 1992;41(RR-17):1-19.

Category B: Symptomatic conditions

These conditions must indicate defective cell-mediated immunity caused by HIV infection, or their clinical course and management must be complicated by HIV. Category B conditions include the following:

• Constitutional symptoms (fever >38.5° C or diarrhea) lasting more than 1 month

• Candidiasis: oropharyngeal or persistent or recurrent vulvovaginal

• Moderate or severe cervical dysplasia or carcinoma in situ

• Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Category C: AIDS-defining illnesses

Including bacterial, viral, fungal infections, parasitic infestations, and some cancers

• Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection at any site, pulmonary or extrapulmonary

• Mycobacterium avium complex disease; infection with Mycobacterium kansasii or other species, disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Mycobacterium, any species disseminated or extrapulmonary

• Lymphoma (Burkitt, immunoblastic, or primary lymphoma of the brain)

• Cancers and chronic renal failure associated with AIDS and lipodystrophy, insulin resistance, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular complications of HAART are being increasingly recognized and addressed.

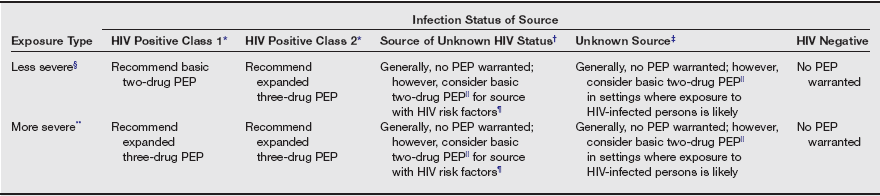

The best defense is a good offense, and there is no substitute for strict adherence to universal precautions. If despite these efforts you or a coworker are exposed to HIV, postexposure prophylaxis is available. Because most occupational exposures do not result in HIV transmission, the guidelines for postexposure prophylaxis weigh the relative risk of infection against the potential toxicity of treatment. The relative risk of infection depends on both the type and amount of blood exposure. The risk of transmission is increased by (1) percutaneous exposure, (2) devices contaminated with visible blood, (3) hollow-bore needles, and (4) high viral titer (i.e., a patient late in the course of the disease). The three classes of antiretroviral agents recommended for prophylactic treatment include nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors. All are associated with a number of toxicities. A basic two-drug regimen is most often recommended, with an expanded three-drug regimen reserved for high-risk exposure (see table on pg. 118). The U.S. Public Health Service guidelines recommend that clinicians consider known drug resistance in their area or documented drug resistance in the source patient, or both, when selecting a prophylactic protocol. The duration of treatment is 4 weeks.

Recommended HIV Postexposure Prophylaxis (PEP) for Percutaneous Injuries

*HIV positive, class 1—asymptomatic HIV infection or known low viral load (e.g., <1500 RNA copies/mL). HIV positive, class 2—symptomatic HIV infection, AIDS, acute seroconversion, or known high viral load. If drug resistance is a concern, obtain expert consultation. Initiation of PEP should not be delayed pending expert consultation, and because expert consultation alone cannot substitute for face-to-face counseling, resources should be available to provide immediate evaluation and follow-up care for all exposures.

†Source of unknown HIV status (e.g., deceased source person with no samples available for HIV testing).

‡Unknown source (e.g., a needle from a sharps disposal container).

§Less severe (e.g., solid needle and superficial injury).

||The designation “consider PEP” indicates that PEP is optional and should be based on an individualized decision between the exposed person and the treating clinician.

¶If PEP is offered and taken and the source is later determined to be HIV negative, PEP should be discontinued.

**More severe (e.g., large-bore hollow needle, deep puncture, blood visible on device, or needle used in a patient’s artery or vein).

From U.S. Public Health Service: Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep 50(RR-11):1-42, 2001.

Anesthesic considerations

HIV-infected patients may require a variety of surgical interventions. Although several studies have evaluated the effects of surgery and anesthesia in HIV-infected patients, to date there is no conclusive evidence to support any particular set of recommendations. Most alterations caused by various anesthetic agents and techniques are transient and have not been shown to contribute to any adverse outcome.

It is important to understand the patient’s status both in response to and the application of antiretroviral therapy and other treatments when an operative procedure is planned. Appreciation of both recent and past therapeutic efforts and the patient’s response is important in preparing the HIV-infected patient for anesthesia and related care. Consultation with and participation of the patient’s primary care provider in the planning process can be beneficial.

When anesthesia care is planned, attention should focus on possible end-organ and systemic dysfunction. Clinically significant alterations occur in many organ systems, particularly in the advanced disease stages of HIV infection, when vigilant monitoring and, at times, intensive intervention may be necessary. The patient (or his or her legal representative or caregiver) should be included in the planning and evaluation of potential care options. Informed consent may be the responsibility of a legal guardian or durable power of attorney designee for the patient who may be mentally incompetent.

The immunocompromised patient may have combined deficiencies that predispose to significant or fatal outcomes. It is important to remember that microorganisms that are not routinely pathogenic can cause the demise of these patients. Meticulous implementation of infection control measures throughout the perioperative period should be a primary focus in the care of these vulnerable patients. Respiratory isolation should be used when it is either known or suspected that airborne pathogens may be transmitted. Examples of such pathogens include the causative agents of tuberculosis and varicella. The immune system compromise resulting from HIV infection markedly increases the susceptibility to tuberculosis, and recurrent or newly acquired tuberculosis is frequently the cause of death for persons infected with HIV. A striking clinical feature of tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients is a high incidence of extrapulmonary involvement, usually with concomitant pulmonary presentation.

Although equipment preparedness is important for every patient to whom anesthesia is administered, it is of particular significance for immunocompromised patients. Meticulous attention to behaviors and adherence to strict aseptic technique in providing care to these most vulnerable patients are paramount to safe practice and quality patient care. The anesthesia machine and its multitude of components should be adequately maintained, cleaned, and disinfected, and appropriate sterile components should be changed between each use in accordance with both approved infection control practices and manufacturers’ recommendations.

A multitude of clinical presentations have the potential to affect anesthesia management in patients infected with HIV. Oxygenation and metabolic functions are frequently impaired during progressive HIV infection. Pulmonary infections can alter both gas exchange and lung perfusion and create ventilation–perfusion mismatch. Dehydration and hypovolemia secondary to gastrointestinal disturbances can further complicate the patient’s clinical course. A thorough preoperative assessment, including current physical examination, laboratory results, and radiographic examination, combined with other studies as indicated by patient presentation and current disease state, is critical before anesthesia.

Complications from HIV

Wasting syndrome may be seen in HIV-infected patients and results from disturbances in food absorption and metabolism. This syndrome is defined as profound, involuntary weight loss greater than 10% of baseline body weight. Chronic diarrhea frequently contributes to this scenario. Parenteral nutrition and appetite stimulation are usually required when this syndrome is persistent. Preoperative assessment should include evaluation of volume status and related physiologic studies to plan appropriate management.

Neurologic evaluation is essential for HIV-infected patients. Both the central and peripheral nervous systems can be impaired because of direct disease effects, concomitant opportunistic infections, or adverse effects of therapeutic agents used to combat viral insult. Peripheral neuropathies may result in considerable discomfort or physical limitations, and autonomic neuropathy may result in some degree of cardiovascular instability requiring immediate or continuous intervention. AIDS-related dementia can influence both motor and cognitive states, particularly in advanced disease states.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, manifesting as a space-occupying lesion within the central nervous system, may require surgical or chemotherapeutic intervention. Kaposi’s sarcoma, a cancer that invades endothelial tissues, can attack both skin and internal organs. Women infected with HIV may develop cervical dysplasia and cancers.

As HIV infection progresses to AIDS, advanced disease combinations emerge that would otherwise be resisted in the immunocompetent host. These opportunistic disease processes increase in both manifestation and severity as the immune system fails. Both acute and chronic bacterial infections tend to plague HIV-infected individuals. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI) infection is characterized by intractable diarrhea and resultant wasting states. Splenic and pulmonary infections with MAI lead to severe thrombocytopenia and tuberculosis. MAI attacks the immunosuppressed host easily and is transmittable.

Several viral infections can occur or recur from previously dormant states as HIV disease progresses. Herpes simplex and varicella infections can invade oral and esophageal tissues and the central nervous system. Cytomegalovirus can affect the gastrointestinal and pulmonary systems, resulting in colitis and pneumonia. Retinal invasion may lead to marked visual disturbances and blindness. Ganciclovir is used to treat cytomegalovirus infection.

Opportunistic protozoal infections can develop in persons with advanced HIV infection. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia is responsible for the majority of deaths secondary to opportunistic infection in HIV-infected persons. Fever and impaired gas exchange frequently result in hypoxemia, and pneumothorax is not uncommon. Toxoplasmosis encephalitis can affect both central nervous system function and the sensorium. Cryptosporidiosis can trigger considerable diarrhea, resulting in significant dehydration and related electrolyte imbalance. Volume status must be judiciously evaluated and monitored.

Fungal infection is responsible for histoplasmosis and aspergillosis pneumonia in HIV-infected patients. Such insults can result in significant febrile and hypoxic states, with impairment of gas exchange and overall sensorium. Disseminated candidiasis infections are responsible for oropharyngeal and esophageal pathology that includes stomatitis, dysphagia, and esophagitis. Patients with cryptococcal meningitis can experience increased intracranial pressure.

Childbearing women constitute a significant portion of reported cases of HIV and AIDS. This is of considerable significance because perinatal transmission accounts for greater than 80% of all pediatric AIDS cases that have been reported in the United States. Pregnant patients with HIV present unique challenges for health maintenance. In advanced stages of HIV infection, anemia can be particularly significant, frequently necessitating transfusion therapy. Elective cesarean section in HIV-positive parturients appears to reduce the risk of HIV transmission from mother to neonate. However, complications of cesarean section, including blood loss and wound infection, may be exaggerated in HIV-infected parturients as a result of immunosuppression.

Because many physical manifestations of HIV-related illness involve neuromuscular disorders, pain management can be a difficult challenge in patients with advanced HIV infection. Both routine analgesic modalities and analgesic agents combined with the use of various chemotherapies, nerve blocks, and complementary therapies have been beneficial in treating acute postoperative and obstetric pain in HIV-infected patients.

Managing HIV infection

Occupational safety: The primary emphasis in managing HIV infection during anesthesia and other aspects of patient care is an effective prevention program. Because the routes of HIV transmission are well known, an appropriate infection control program with consistent application of proven blood and body substance precautions can prevent disease transmission. Universal precautions were developed after known modes of transmission of both HIV and hepatitis B virus (both bloodborne pathogens) were clarified. More recent efforts to apply this practice throughout all patient care areas have resulted in the consistent application of standard precautions during patient care. The basic premise on which these guidelines is based is the prevention of parenteral, mucous membrane, and nonintact skin exposure to blood and certain body fluids from all patients. Guidelines include the following:

1. Gloves must be worn when contact with body substances is suspected or possible.

2. A plastic gown or apron must be worn when soiling with body substances is likely.

3. Protective masks and eyewear must be worn in the presence of airborne disease or for preventing splash or aerosolization of body substances to eyes or mucous membranes.

4. Hands must be thoroughly washed before and after body substances or articles possibly covered with body substances have been handled and after gloves have been removed at the completion of each task or procedure.

5. Uncapped needles and syringes must be discarded in puncture-resistant receptacles placed as close to their point of use as is practical.

6. Trash and linens must be discarded in impervious, sealed plastic bags that are labeled as infectious and transported according to standard precautions.

Self-protection against HIV and all other infectious bloodborne pathogens such as hepatitis B and C viruses is an essential element of safe practice. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Act, which became effective in 1992, mandates that employers minimize occupational exposure to all bloodborne pathogens in workplaces where a potential for such exposures exists. Known or suspected exposure to bloodborne pathogens should be responded to immediately with appropriate action, as recommended by OSHA and institutional infection control standards.

B Anemia

Definition

Anemia is a deficiency of erythrocytes caused by either too rapid a loss or too slow production of the cells. Therefore, numeric concentrations of hemoglobin are reduced, and the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood is decreased. This results in reduced oxygen delivery to peripheral tissues.

Pathophysiology

Anemia may result from acute blood loss; however, iron-deficiency anemia from persistent blood loss is the most frequent form of chronic anemia. Anemia is also associated with many chronic diseases, such as persistent infections, neoplastic processes, connective tissue disorders, and renal and hepatic disease. Other forms of anemia include aplastic anemia, which involves bone marrow depression, and megaloblastic anemias, which are related to deficiencies of vitamin B12 or folic acid. Finally, various anemias can result from intravascular hemolysis of erythrocytes.

Laboratory results

Erythrocyte production can be assessed from the reticulocyte count in peripheral blood. For instance, a low reticulocyte count in the presence of a low hematocrit suggests an erythrocyte production defect, rather than blood loss or hemolysis, as a cause of anemia. A decrease in hematocrit that exceeds 1% per day is most likely related to acute blood loss or intravascular hemolysis.

Clinical manifestations

A history of reduced exercise tolerance characterized as exertional dyspnea is a frequent clinical sign of chronic anemia. A functional heart murmur and evidence of cardiomegaly may be detected on physical examination. The decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of arterial blood is reflected in the arterial oxygen content equation (i.e., arterial oxygen content = [hemoglobin × 1.39] × oxygen saturation + [arterial oxygen tension × 0.003]). This decrease is compensated for by a rightward shift oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve and an increase in cardiac output. Decreased blood viscosity and vasodilation lower systemic vascular resistance and increase blood flow. Blood pressure and heart rate remain unchanged with increased cardiac output. The decreased exercise tolerance reflects the inability of cardiac output to increase to maintain tissue oxygenation when these patients become physically active.

Treatment

Packed erythrocytes can be transfused preoperatively to increase hemoglobin concentrations, with peak effect at 24 hours to restore intravascular fluid volume and blood viscosity. Compared with a similar volume of whole blood, erythrocytes produce about twice the increase in hemoglobin concentration. Packed red blood cells have a hematocrit of 70%, and cell saver has a hematocrit of 45% to 65%.

Anesthetic considerations

Transfusion guidelines include assessment of the patient’s cardiovascular status, age, anticipation of further blood loss, arterial oxygenation, mixed venous oxygen tension, cardiac output, and infection risk. (Minimum acceptable hemoglobin concentrations for elective surgery have changed over the years. The “old” value of 10 g/dL has been lowered to approximately 8 g/dL, depending on the patient’s preoperative status, intraoperative status, operation, and institution.) The presence of neurovascular and cardiovascular disease can diminish blood flow to the brain and heart. Further decreasing oxygen delivery to these tissues caused by anemia can result in acute stroke or myocardial ischemia or infarction. If elective surgery is performed, the anesthetic regimen should be geared toward preventing changes that may interfere with tissue oxygen delivery. Adequate oxygenation can be obtained with a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL as long as the patient is normovolemic. For example, myocardial depression produced by volatile agents may reduce cardiac output and thus impair the patient’s compensatory mechanisms. Likewise, leftward shifts of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve (as produced by hyperventilation resulting in respiratory alkalosis) can impair release of oxygen from hemoglobin to the tissues. It is also important to maintain body temperature because hypothermia will cause a leftward shift of the curve. Intraoperative blood loss should be promptly replaced and closely monitored. Finally, it is important to minimize shivering or increases in body temperature postoperatively because these changes can greatly increase total body oxygen requirements.

C Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Definition

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a coagulation disorder characterized by ongoing activation of the coagulation cascade in response to a clinical or systemic event. Organ damage and death are the result of widespread microvascular bleeding and thrombosis.

Pathophysiology

The diagnosis of DIC is usually secondary to a systemic illness or insult. Coagulation activation ranges from mild thrombocytopenia and prolongation of clotting times to acute DIC characterized by extensive bleeding and thrombosis. During overactive coagulation, the available platelets and coagulation factors are consumed. This consumption along with fibrinolysis exhausts the hemostatic balance. Rarely is the primary cause a coagulation deficiency or dysfunction.

Several factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of DIC, including the propagation of thrombin, alteration in anticoagulant activity, impaired functioning of the fibrinolytic system, and the release of cytokines. Tissue factor release is considered to play the most important role in the development of a hyperthrombinemia in DIC. Mediators such as antithrombin and tissue factor pathway inhibitor that normally inhibit coagulation are altered. Reasons for this impairment include septicemia, liver impairment, capillary leakage, and the release of endotoxins and proinflammatory cytokines. The initial increased fibrinolytic activity is followed by the release of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1), which in turn impairs fibrinolysis and leads to accelerated thrombus formation in DIC. And, lastly, activated protein C mediates the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and ILs from endothelial cells. Complement activation and kinin generation increase the coagulation response, leading to subsequent vascular occlusion.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of DIC is made by considering the patient’s clinical picture in conjunction with laboratory tests (platelet count, activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT], prothrombin time [PT], fibrin-related markers such as fibrin degradation products, D dimer, fibrinogen, and antithrombin). Additionally, a scoring system developed by the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis assists with the diagnosis. Overt (acute) DIC is characterized by ecchymosis, petechiae, mucosal bleeding, depletion of platelets, clotting factors, and bleeding at puncture sites. A score of 5 or above is comparable with overt DIC. Nonovert (chronic) DIC is characterized by thromboembolism accompanied by evidence of activation of the coagulation system. A score of below 5 is suggestive for nonovert DIC.

Treatment

The management and treatment of patients with DIC always depends on the underlying cause. In obstetric catastrophes, DIC may resolve as a result of prompt delivery, and treatment of sepsis with antibiotic therapy may halt the progression of DIC. Restoration of physiologic anticoagulant pathways with activated protein C in the treatment of sepsis with overt DIC holds promise. Activated protein C inactivates factors Va and VIIIa, resulting in decreased thrombin formation. Its use in treating patients with severe sepsis in DIC has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. For individuals requiring surgery who are bleeding or at risk for active bleeding, correction of coagulopathy with platelets (<50,000/mm3), fresh-frozen plasma, and cryoprecipitate (fibrinogen <50 mg/dL) must be used. Continued replacement of blood products should be based on the clinical picture and reassessment of laboratory results.

The use of anticoagulants for DIC remains controversial, especially for a patient who is prone to bleeding. Also, the use of antithrombin III concentrates may prove effective in inhibiting coagulation; however, its use is yet to be conclusive.

D Hemophilia

Definition and incidence

Hemophilia is an X-linked recessive disorder. It is a hematologic disorder of unpredictable bleeding patterns. Patients are either deficient in factor IX (hemophilia A) or factor VIII:C (hemophilia B). Hemophilia affects males, and females are carriers of the disease.

Pathophysiology

Hemophilia A is grouped into mild (bleeding surfaces after trauma or surgery), moderate (rarely have extensive unprovoked bleeding), and severe (absence of factor VIII:C in the plasma) forms. People with hemophilia exhibit spontaneous bleeding, muscle hematomas, and generalized joint pain. Continued joint bleeding often results in decreased range of motion and progressive joint arthropathy and often requires orthopedic surgical intervention throughout their lives. Hemophiliacs also exhibit excessive bleeding after trauma.

Anesthetic considerations

For patients with hemophilia or a family history of hemophilia, a preoperative assessment of hemostasis is imperative. Preoperative laboratory tests should include a platelet count and function, a coagulation panel (PT, partial thromboplastin time [PTT], factor VIII, factor IX, and fibrinogen), as well as an inhibitor test. If the hemophiliac was given a test dose of factor VIII preoperatively, the response to the test dose should be evaluated. The patient should be typed and cross-matched because even a low-risk procedure for bleeding can be catastrophic for patients with hemophilia.

A clearly defined anesthesia plan is essential for patients with hemophilia because uncontrolled bleeding is certainly a possibility. Factor VIII concentrated can be given before surgery. Factor VII is administered intraoperatively to augment thrombin generation and deter bleeding. The dose should be precalculated and vial availability confirmed before going into the operating room. Desmopressin (0.3 mcg/kg) can also be administered to increase plasma levels of factor VIII:C and von Willebrand factor VIII for mild to moderate hemophilia. There is no risk for viral transmission when either of these drugs is administered.

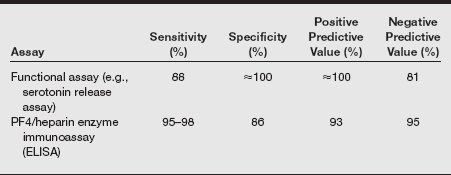

E Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

Definition and incidence

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a disorder of coagulation that is a direct consequence of heparin therapy. One of the few relative versus absolute contraindications to heparin therapy is HIT. In the United States, a yearly estimate of 600,000 new cases of HIT occur, with as many as 300,000 patients developing thrombotic complications and 90,000 patients dying.

Pathophysiology

HIT is a special case of drug-induced immune-mediated thrombocytopenia associated with arterial and venous thrombosis, rather than bleeding. It is seen in 2% to 5% of patients exposed to unfractionated heparin and in 0.7% of patients given low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH); it almost never occurs in patients exposed only to fondaparinux. To understand this disease, one must know that platelets can secrete a protein, platelet factor 4 (PF4), that can bind to heparin. HIT is caused by an antibody that binds to this PF4–heparin complex. Large complexes of antibodies directed against heparin-bound PF4 accumulate on the surface of platelets. At times, these anti-PF4 immunoglobulins bind to the Fc receptor that is also present on the platelet surface. The interaction of platelet Fc receptors and anti-PF4 antibodies causes activation of the platelet, release of more PF4, and a cycle of events that leads to the stimulation of even more platelets. Ultimately, it also leads to activation of the coagulation cascade. The activation of platelets and the clotting cascade leads to the formation of thrombi and thrombocytopenia.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia typically occurs 4 to 14 days after patients are given heparin by any route (even subcutaneously or in extremely low doses by heparin flush). This lag between heparin exposure and the appearance of HIT is due to the time it takes for the immune response to generate the requisite antibodies against the heparin–PF4 complex. Some patients who have been exposed to heparin within the past several months already have preexisting antibodies, and they may develop an acute onset of HIT within the first day of reinitiating the drug.

If a patient has HIT, all heparin should be stopped immediately. This includes subcutaneous injections of “minidose” heparin, heparin flushes of intravenous lines, and LMWH; even heparin-coated intravenous catheters should be withdrawn. Alternative anticoagulation, such as a direct thrombin inhibitor such as recombinant hirudin or argatroban, should be administered, at least until the platelet count normalizes. Warfarin should not be used in cases of acute HIT because of its delayed therapeutic effect and its association with venous limb gangrene. Because patients rarely become profoundly thrombocytopenic as a result of HIT alone, platelet transfusions are typically not required. In fact, some reports suggest that platelet transfusions can actually precipitate thrombotic complications, although this remains controversial.

F Leukemia

Definition

Leukemia is the uncontrolled production of leukocytes caused by cancerous mutation of lymphogenous cells or myelogenous cells. Lymphocytic leukemias begin in lymph nodes or other lymphogenous tissues and then spread to other areas of the body. Myeloid leukemias begin as cancerous production of myelogenous cells in bone marrow, with spread to extramedullary organs. Cancerous cells usually do not resemble other leukocytes and lack the usual functional characteristics of white blood cells. Leukemia cells may infiltrate the liver, spleen, and meninges and produce signs of dysfunction at these sites.

Incidence, pathophysiology, laboratory results, and treatment

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia accounts for approximately 15% of all leukemias in adults. Central nervous system dysfunction is common. These patients are highly susceptible to life-threatening infections, including those produced by Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) and cytomegalovirus.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia accounts for approximately 25% of all leukemias and is most common in elderly men. The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of lymphocytosis (>15,000/mm3) and lymphocytic infiltrates in bone marrow. There may be neutropenia with an associated increased susceptibility to bacterial infections. Treatment is with cancer chemotherapeutic drugs classified as alkylating agents.

Acute myeloid leukemia can result in death in about 3 months if untreated. Patients present with fever, weakness, bleeding, and hepatosplenomegaly. Chemotherapy produces a temporary remission in about half of patients.

Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia present with massive hepatosplenomegaly and white blood cell counts greater than 50,000/mm3. Fever and weight loss reflect hypermetabolism. Anemia may be severe. Splenectomy is routine in these patients.

Chemotherapy is the best available therapy for irradiation of cancerous cells anywhere in the body. Adverse clinical effects of these drugs include bone marrow suppression (susceptibility to infection, thrombocytopenia, and anemia), nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, ulceration of the gastrointestinal mucosa, and alopecia. Destruction of tumor cells by chemotherapy produces a uric acid load that may result in urate nephropathy and gouty arthritis. Bone marrow transplantation is also becoming an increasingly successful treatment for leukemia.

Anesthetic considerations

Management of anesthesia for patients with leukemia requires a clear understanding of the mechanisms of action, potential interactions, and likely toxicities associated with the use of cancer chemotherapeutic drugs. Patients taking doxorubicin or daunorubicin (antibiotics) may develop cardiomyopathy leading to congestive heart failure, which is often refractory to cardiac inotropic drugs. Cardiomegaly or pleural effusions may be found on chest radiographs. Marked left ventricular dysfunction was found to persist for as long as 3 years after the drug was discontinued. Nonspecific and usually benign electrocardiographic changes have been observed in 10% of patients. Bleomycin is an antibiotic that can cause pulmonary toxicity, with dyspnea and nonproductive cough being the initial manifestations. Pulmonary function tests demonstrate “restrictive” pulmonary disease. The inspired fraction of oxygen should be maintained at less than 30% during surgery because patients are susceptible to the toxic pulmonary effects of oxygen while they are receiving bleomycin therapy.

Strict aseptic technique is important because of immunosuppression. Preoperatively, signs of central nervous system depression, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and peripheral neuropathies should be noted. Renal or hepatic dysfunction should influence the choice of anesthesia and muscle relaxants. Volatile anesthetics may reduce myocardial contractility in patients with cardiotoxicity related to chemotherapeutic drugs (i.e. Adriamycin). Arterial blood gases should be monitored. Replacing fluid losses with colloid rather than crystalloid solutions in patients with pulmonary fibrosis may be considered. In addition, possible postoperative ventilation, depending on the length of the procedure and the degree of fibrosis, should be considered. Other considerations include:

• A risk of infection from immunosuppression exists.

• Renal function is affected by uric acid production.

• A thorough neurologic assessment related to chemotherapy treatment is indicated.

• Patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia may develop malignant hyperthermia.

• Nitrous oxide should be avoided in bone marrow transplantation. (The use of nitrous oxide in patients donating bone marrow or undergoing bone marrow transplantation should be avoided because of the potential for drug-induced adverse effects on the bone marrow itself. Donors may be given heparin before removal of bone marrow, and anticoagulation can complicate the use of spinal or epidural anesthesia for this procedure.)

G Polycythemia vera

Definition and pathophysiology

Polycythemia vera is a myeloproliferative neoplastic disorder that generally occurs in patients between 60 and 70 years of age. Hyperactivity of myeloid progenitor cells results in increased production of erythrocytes, leukocytes, and platelets.

Laboratory results

Hemoglobin concentrations typically exceed 18 g/dL, and platelet counts can be greater than 400,000/mm3.

Clinical manifestations

Clinical symptoms are the result of hyperviscosity of the blood, which leads to stasis of blood flow and an increased incidence of vascular thrombosis, particularly in the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. Erythromelalgia (burning pain) in the fingers and toes is caused by digital ischemia. Defective platelet function is the most likely mechanism for spontaneous hemorrhage, which may occur in these patients. Splenomegaly is often present.

Treatment

Treatment entails reducing the hematocrit to near-normal levels to about 40% by phlebotomy before elective surgery.

Anesthetic considerations

Surgery in the presence of uncontrolled polycythemia vera is associated with a high incidence of perioperative hemorrhage and postoperative venous thrombosis. In emergency situations, viscosity of the blood can be reduced by intravenous infusions of crystalloid solutions or low-molecular-weight dextrans. NPO (nothing by mouth) fluid replacement should be infused early to assist in decreasing blood viscosity.

H Sickle cell disease

Pathophysiology

Sickle cell is a disorder transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait that causes an abnormality of the globin genes in hemoglobin. A person who is homozygous for hemoglobin S manifests the disorder. Individuals may have the sickle cell trait or sickle cell disease. The sickle cell trait is a heterozygous disorder seen in 10% of African Americans. Their hemoglobin S levels are normally 30% to 50%, and sickling is seen with a Po2 of 20 to 30 mmHg. Sickle cell disease is a homozygous disorder seen in 0.5% to 1.0% of African Americans. The majority of the hemoglobin molecule is hemoglobin S, and sickling is seen with a Po2 of 30 to 40 mmHg. A crisis may be caused by a decrease of oxygen saturation and temperature, infections, dehydration, stasis, or acidosis. These complicated scenarios translate into perioperative mortality rates of 10% and postoperative complications of 50%.

Anesthetic considerations

Suggestions for intraoperative management of patients with sickle cell disease are listed in the following box.

There is no universal method for caring for patients with a sickle cell disorder. It is suggested that patients with a preoperative hemoglobin A level of at least 50% and a hematocrit of at least 35% may have less risk of an intraoperative crisis as an effort is made to correct anemia. By providing preoperative transfusion supplement, there is a risk of increasing the blood’s viscosity causing end-organ damage. Anesthesia management that includes adequate hydration, saturation, normothermia, normal acid–base balance, and proper positioning and analgesia may interrupt an intraoperative and postoperative crisis.

I Thalassemia

Definition

Thalassemia is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder resulting in a person’s inability to synthesize structurally normal hemoglobin.

Pathophysiology

Patients have a genetic inability to synthesize structurally normal hemoglobin. Thalassemia major reflects an inability to form the chains of hemoglobin. As a result, adult hemoglobin A is not formed, and anemia develops during the first year of life as fetal hemoglobin disappears. Thalassemia minor reflects a heterozygote state that results in mild anemia. Thalassemia results from the lack of production of chains of adult hemoglobin. The homozygous form of thalassemia is incompatible with life, resulting in intrauterine demise or early neonatal death.

Clinical manifestations

Thalassemia major is associated with jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, and susceptibility to infection. Death can result from cardiac hemochromatosis. Supraventricular cardiac dysrhythmias and congestive heart failure are common. Hemothorax and spinal cord compression may occur secondary to massive extramedullary hematopoiesis and destruction of vertebral bodies. Overgrowth of the maxillae can make visualization of the glottis difficult during direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation.

In thalassemia minor, a relatively normal RBC count distinguishes anemia caused by thalassemia minor from iron-deficiency anemia. Finally, the homozygous form of thalassemia is incompatible with life; the heterozygous presentation usually results in mild hypochromic and microcytic anemia.

Treatment

Treatment varies depending on variant form. Patients with β-thalassemia major can be treated with hydroxyurea. Occasionally, bone marrow transplantation may be recommended in these patients, and a splenectomy may be necessary if hypersplenism leads to pancytopenia. For α-thalassemia, blood transfusion is occasionally necessary.

J Von willebrand disease

Definition

von Willebrand disease (vWD) has traditionally remained the most common inherited coagulation diathesis. von Willebrand factor (vWF) VIII is a heterogeneous multinumeric glycoprotein that serves two main functions: to facilitate platelet adhesion and to behave as a plasma carrier for factor VIII:C of the coagulation cascade. vWF is synthesized in the endothelial cells and in megakaryocytes. An acquired form of vWD:VIII is seen with lymphomyeloproliferative or immunologic disease states secondary to antibodies against vWF:VIII.

Clinical manifestations

Similar to many coagulopathies, vWD:VIII has varying degrees of severity: mild, moderate, and severe. In the milder or moderate forms, regular or spontaneous bleeding is not evident, but it is likely after surgery or when trauma occurs. In the more severe form, spontaneous epistaxis and oral, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary bleeding can be relentless.

Anesthetic considerations

Most patients with vWF:VIII exhibit a prolonged bleeding time, a deficiency in vWF:VIII, decreased vWF:VIII activity measured by a ristocetin(an antibiotic) cofactor assay, and a decreased VIII:C. The recommended treatment for vWF:VIII is to supplement with recombinant factor VIII preoperatively and to administer it during surgery to raise the level of circulating vWF:VIII. Cryoprecipitate is another means of acquiring factor VIII; however, there is a risk of viral transmission. DDAVP (synthetic vasopressin) is an excellent option for the milder forms and should not be overlooked. DDAVP helps to increase plasma levels of vWF:VIII and augment aggregation.