Syphilis

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Describe the etiology; epidemiology; and signs and symptoms of primary, secondary, latent, and late (tertiary) syphilis.

• Describe the origin and manifestations of congenital syphilis.

• Explain the immunologic manifestations and diagnostic evaluation of syphilis.

• Analyze a case study related to syphilis testing.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Discuss the principles and clinical applications of the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) card test and VDRL procedure.

• Discuss the principles and clinical applications of confirmatory syphilis testing, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA) test.

The disease syphilis was reported in the medical literature as early as 1495. In 1905, it was discovered that syphilis was caused by a spirochete type of bacteria, Treponema pallidum (originally called Spirochaeta pallida). The first diagnostic blood test for syphilis was the Wassermann test, a complement fixation test developed in 1906. This classic procedure (see www.mlturgeon.com, “Archives of Classic Procedures”) has subsequently been replaced by a variety of methods. In the treatment of syphilis, heavy metals, such as arsenic, were replaced by penicillin in the 1940s. Penicillin continues to remain the drug of choice for the treatment of this disease.

Etiology

T. pallidum is a member of the order Spirochaetales and the family Treponemataceae (Fig. 18-1). The genus Treponema includes a number of species that reside in human gastrointestinal and genital tracts. T. pallidum, Treponema pertenue, and Treponema carateum are human pathogens responsible for significant worldwide morbidity (Table 18-1). Yaws, pinta, and bejel are diseases caused by bacteria closely related to T. pallidum. Yaws is common in the Caribbean, Latin America, Central Africa, and the Far East. Pinta is found only in Latin America and infection is limited to the skin. Bejel is found in eastern Mediterranean countries, the Balkans, and the cooler areas of North Africa.

Table 18-1

| Bacteria | Associated Disease |

| T. pallidum | Syphilis |

| T. pallidum (variant) | Bejel |

| T. pertenue | Yaws |

| T. carateum | Pinta |

Signs and Symptoms

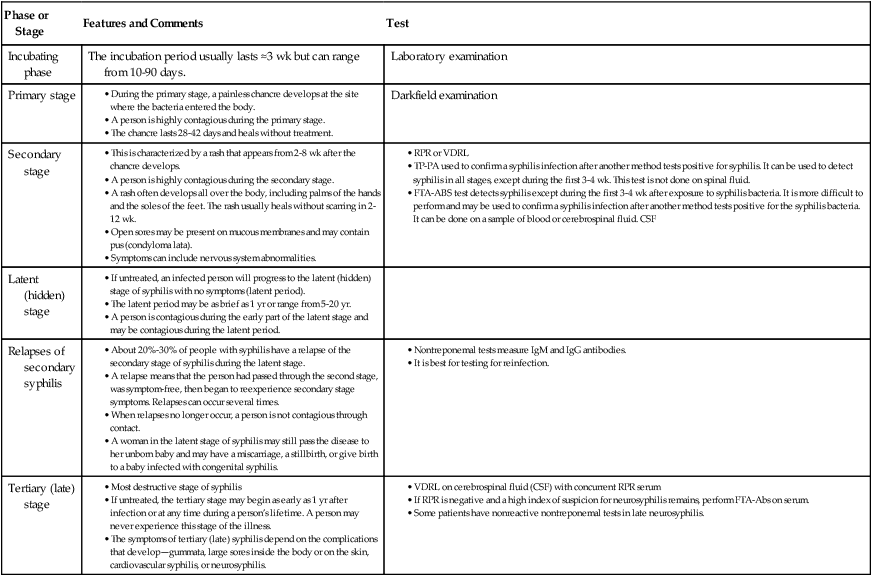

Untreated syphilis is a chronic disease with subacute symptomatic periods separated by asymptomatic intervals, during which the diagnosis can be made serologically. The progression of untreated syphilis is generally divided into stages—primary, secondary, latent (hidden), and tertiary (late) (Table 18-2).

Table 18-2

| Phase or Stage | Features and Comments | Test |

| Incubating phase | The incubation period usually lasts ≈3 wk but can range from 10-90 days. | Laboratory examination |

| Primary stage |

• This is characterized by a rash that appears from 2-8 wk after the chancre develops.

• A person is highly contagious during the secondary stage.

• A rash often develops all over the body, including palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. The rash usually heals without scarring in 2-12 wk.

• Open sores may be present on mucous membranes and may contain pus (condyloma lata).

• TP-PA used to confirm a syphilis infection after another method tests positive for syphilis. It can be used to detect syphilis in all stages, except during the first 3-4 wk. This test is not done on spinal fluid.

• FTA-ABS test detects syphilis except during the first 3-4 wk after exposure to syphilis bacteria. It is more difficult to perform and may be used to confirm a syphilis infection after another method tests positive for the syphilis bacteria. It can be done on a sample of blood or cerebrospinal fluid. CSF

• If untreated, an infected person will progress to the latent (hidden) stage of syphilis with no symptoms (latent period).

• The latent period may be as brief as 1 yr or range from 5-20 yr.

• A person is contagious during the early part of the latent stage and may be contagious during the latent period.

• About 20%-30% of people with syphilis have a relapse of the secondary stage of syphilis during the latent stage.

• A relapse means that the person had passed through the second stage, was symptom-free, then began to reexperience secondary stage symptoms. Relapses can occur several times.

• When relapses no longer occur, a person is not contagious through contact.

• A woman in the latent stage of syphilis may still pass the disease to her unborn baby and may have a miscarriage, a stillbirth, or give birth to a baby infected with congenital syphilis.

• Most destructive stage of syphilis

• If untreated, the tertiary stage may begin as early as 1 yr after infection or at any time during a person’s lifetime. A person may never experience this stage of the illness.

• The symptoms of tertiary (late) syphilis depend on the complications that develop—gummata, large sores inside the body or on the skin, cardiovascular syphilis, or neurosyphilis.

Primary Syphilis

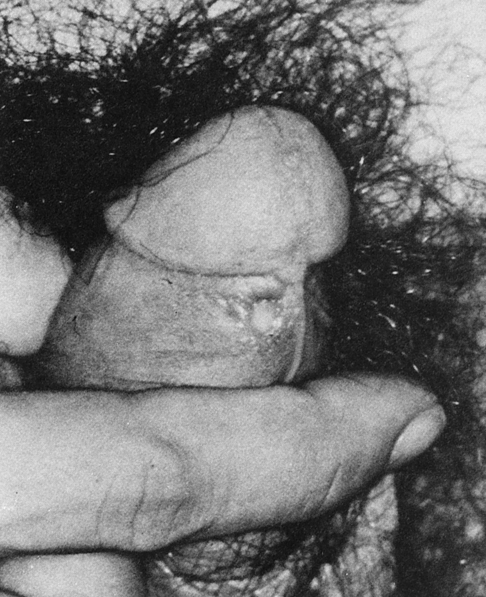

At the end of the incubation period, a patient develops a characteristic, primary inflammatory lesion called a chancre at the point of initial inoculation and multiplication of the spirochetes. The chancre begins as a papule and erodes to form a gradually enlarging ulcer, with a clean base and indurated edge (Fig. 18-2). Generally, it is relatively painless. In most cases, only a single lesion is present, but multiple chancres are not rare.

Secondary Syphilis

Within 2 to 8 weeks (but occasionally as long as 6 months) after the appearance of the primary chancre, a patient may develop the signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. In some patients, primary and secondary syphilis overlap and the chancre is still obvious. Other patients never notice the primary chancre and initially have manifestations of secondary syphilis (Fig. 18-3).

Secondary syphilis usually resolves within 2 to 6 weeks, even without therapy.

Late (Tertiary) Syphilis

Congenital Syphilis

1. Ensure sustained political commitment and advocacy.

2. Increase access to, and quality of, maternal and newborn health services.

3. Screen and treat pregnant women and their partners.

4. Establish surveillance, monitoring and evaluation systems.

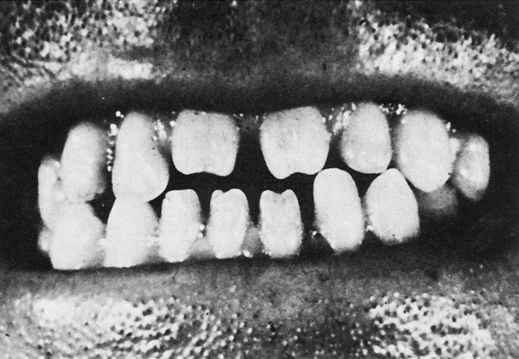

The late stage is seen in children older than 2 years who are untreated. Symptoms of the untreated late stage include eighth nerve deafness, keratitis, and Hutchinson’s teeth (Fig. 18-4) (hutchisonian triad), as well as arthropathy and neurosyphilis. Residual stigmata can develop. Other characteristics include fissuring around the mouth and anus, skeletal lesions, perforation of the palate, and collapse of nasal bones to produce a saddle-nose deformity.

Immunologic Manifestations

In the treponemes, two classes of antigen have been recognized:

Delayed-hypersensitivity immune mechanisms (see Chapter 26) also contribute to the pathophysiology of syphilis. It has been suggested that the granulomatous reactions (gummas) result from delayed hypersensitivity in the immune host. In addition, the manifestations of congenital syphilis apparently result in part from an immune inflammatory reaction. Antigen-antibody complexes have been detected in the blood of patients with secondary syphilis and are responsible for the syphilis-associated glomerulonephritis. Suppression of the various aspects of cell-mediated immunity has been noted in syphilis and may contribute to the prolonged survival of T. pallidum.

Diagnostic Evaluation

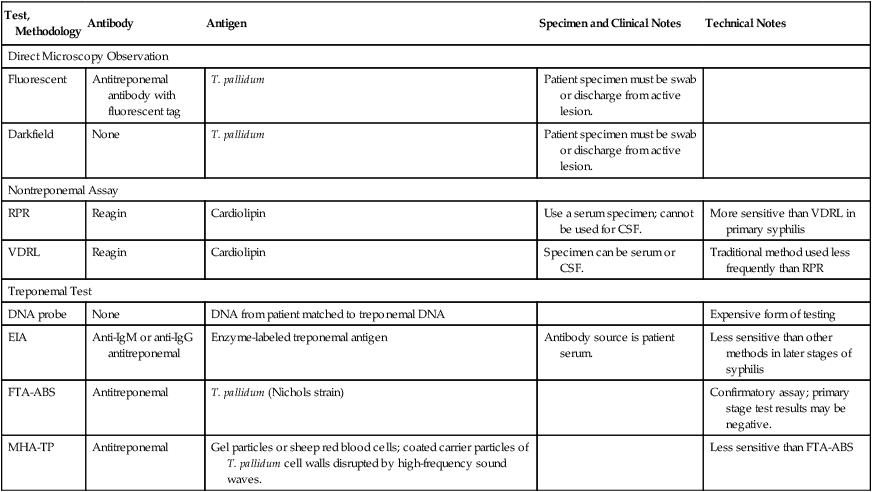

The diagnosis of syphilis depends on clinical skills, demonstration of microorganisms in a lesion, and serologic testing. A variety of diagnostic procedures for syphilis are available (Tables 18-3 and 18-4). Classic serologic methods for syphilis measure the presence of two types of antibodies (Table 18-5), nontreponemal methods and treponemal methods.

Table 18-3

Comparison of Tests for Syphilis Diagnosis

| Test, Methodology | Antibody | Antigen | Specimen and Clinical Notes | Technical Notes |

| Direct Microscopy Observation | ||||

| Fluorescent | Antitreponemal antibody with fluorescent tag | T. pallidum | Patient specimen must be swab or discharge from active lesion. | |

| Darkfield | None | T. pallidum | Patient specimen must be swab or discharge from active lesion. | |

| Nontreponemal Assay | ||||

| RPR | Reagin | Cardiolipin | Use a serum specimen; cannot be used for CSF. | More sensitive than VDRL in primary syphilis |

| VDRL | Reagin | Cardiolipin | Specimen can be serum or CSF. | Traditional method used less frequently than RPR |

| Treponemal Test | ||||

| DNA probe | None | DNA from patient matched to treponemal DNA | Expensive form of testing | |

| EIA | Anti-IgM or anti-IgG antitreponemal | Enzyme-labeled treponemal antigen | Antibody source is patient serum. | Less sensitive than other methods in later stages of syphilis |

| FTA-ABS | Antitreponemal | T. pallidum (Nichols strain) | Confirmatory assay; primary stage test results may be negative. | |

| MHA-TP | Antitreponemal | Gel particles or sheep red blood cells; coated carrier particles of T. pallidum cell walls disrupted by high-frequency sound waves. | Less sensitive than FTA-ABS | |

Table 18-4

Select Tests for Syphilis Diagnosis

| Test | Methodology | Comments |

| Darkfield examination | Darkfield microscopy | |

| RPR | Charcoal agglutination | |

| T. pallidum (VDRL), serum with reflex to titer | Flocculation | |

| T. pallidum antibody, serum IgG by IFA | Indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) | False-positive result in herpes, HIV, malaria, IV drug use, systemic lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, leprosy |

| T. pallidum antibody, IgM by ELISA | ELISA | If test results are questionable, repeat testing in 10-14 days. |

| T. pallidum antibody, IgG by ELISA | ELISA | If test results are questionable, repeat testing in 10-14 days. |

Adapted from Associated Regional and University Pathologists (ARUP) Laboratories: ARUP’s laboratory test directory, 2012 (http://www.aruplab.com/guides/ug/tests/ugs.jsp).

Table 18-5

Nontreponemal and Treponemal Assays

| Nontreponemal Screening Assays | Treponemal Confirmatory‡ Assays |

| T. pallidum (RPR)∗ | FTA-ABS |

| T. pallidum (VDRL)† | T. pallidum particle agglutination (antibody to TP-PA) T. pallidum antibody IgM by ELISA T. pallidum antibody, IgG by Immunoblot T. pallidum antibody, IgG by indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA)§ |

∗Serum or CSF with reflex to titer.

†Serum or CSF with reflex to titer.

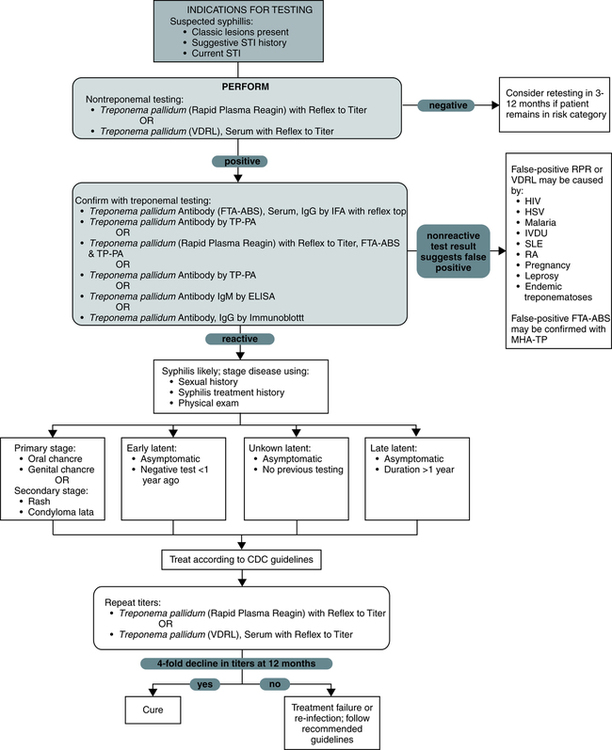

Testing for syphilis can comply with a logical flow of observations and laboratory testing (Fig. 18-5). Seroconversion between acute and convalescent sera is considered strong evidence of recent infection. The best evidence for infection is a significant change in two appropriately timed specimens, in which both tests are performed in the same laboratory at the same time.

Treponemal Methods

• Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS)

• T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA)

• T. pallidum antibody by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

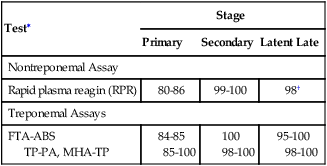

Sensitivity of Representative Procedures for Syphilis

Detection of syphilis by serologic methods is related to the stage of the disease and test method (Table 18-6).

Table 18-6

Percentage of Positive Tests for Syphilis

| Test∗ | Stage | ||

| Primary | Secondary | Latent Late | |

| Nontreponemal Assay | |||

| Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) | 80-86 | 99-100 | 98† |

| Treponemal Assays | |||

| FTA-ABS TP-PA, MHA-TP |

84-85 85-100 |

100 98-100 |

95-100 98-100 |

MHA-TP, Microhemagglutination assay for antibodies directed against T. pallidum.

∗Percentage of patients with positive serologic tests in treated or untreated primary or secondary syphilis.

Adapted from Tramont E: Treponema pallidum. In Mandell GI, Douglas RG Jr, Bennett Jr, editors: Principles and practice of infectious diseases, ed 2, New York, 1985, Wiley & Sons, and LaSalsa L et al: Spirochete infections. In Henry JB, editor: Clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods, ed 21, Philadelphia, 2007, WB Saunders, Table 58-1.

Classic VDRL Procedure: VDRL Qualitative Slide Test

Classic VDRL Procedure: VDRL Qualitative Slide Test

Principle

Sources of Error

False-negative reactions can occur in a variety of situations. These include the following:

3. Presence of inhibitors in the patient’s serum

4. Reduced ambient temperature (<23° C to 29° C [<73° F to 84° F])

Weakly reactive results can be caused by the following:

Contaminated or hemolyzed specimens can also produce false-positive results.

Chapter Highlights

• Syphilis is caused by a spirochete, Treponema pallidum, usually transmitted in humans by sexual contact.

• Untreated syphilis is a chronic disease with subacute symptomatic periods separated by asymptomatic intervals, during which the diagnosis can be made serologically. The progression of untreated syphilis is generally divided into stages.

• In primary syphilis, the serum in about one third of cases becomes serologically reactive after 1 week and serologically demonstrable in most cases after 3 weeks. The reagin titer increases rapidly during the first 4 weeks and then stabilizes for about 6 months.

• Two to 8 weeks after the appearance of the primary chancre, the patient enters the stage of secondary syphilis, usually characterized by generalized illness suggestive of a viral infection. Skin lesions contain spirochetes and are highly contagious on exposed surfaces. These lesions subside spontaneously after 2 to 6 weeks, even if untreated. In this noninfectious latent stage, serologic tests for syphilis are positive.

• The late (tertiary) stage usually occurs 3 to 10 years after primary infection; gummas can appear in about 15% of untreated syphilitic persons who eventually develop late benign syphilis. Complications include nervous system lesions, causing tabes dorsalis or cardiovascular complications. The tertiary stage is asymptomatic and determined only by serologic testing. Occasionally, the lesions heal so completely that even serologic tests become nonreactive.

• Classic serologic tests for syphilis measure the presence of two types of antibodies, treponemal and nontreponemal.

• Darkfield microscopy is the test of choice for symptomatic patients with primary syphilis.

• The widely used nontreponemal serologic test is the RPR method, a flocculation method.

• Specific treponemal serologic tests include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) and T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA).