Syncope

Perspective

Syncope is the sudden transient loss of consciousness with a loss of postural tone. It is a common presenting complaint in the emergency department (ED). Despite improved understanding of risk and outcomes, consensus on the diagnostic approach and disposition remains elusive. This is in part because of the varied causes of syncope and lack of definitive diagnostic studies, and in part because of confusion and lack of standard terminology to describe the disorder.1 Diagnostic accuracy relies largely on the synthesis of patient risk factors and reported symptoms, with limited reliance on the physical examination and ancillary testing.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of syncope in the general population is approximately 19%.2 Patients come to the ED at a rate of 2.8 visits per 1000 population, which accounts for 0.8% of ED visits.2,3 Approximately 32% of these patients are admitted, and syncope accounts for 1 to 6% of all hospitalized patients.2,4 Persons aged 65 years and older account for 80% of such admissions. In the pediatric population, 15% experience at least one episode of syncope.

Risk factors for syncope include cerebrovascular disease, cardiac medications, and hypertension.5 Most causes of syncope are benign and have favorable outcomes. Patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease and syncope from any cause are at the greatest short- and long-term risk of mortality.4,6 Age, congestive heart failure, and coronary artery disease are key predictors of mortality in patients with syncope, but syncope alone does not appear to alter risk.7 In contrast, there is no increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity or mortality associated with neurocardiogenic (vasovagal), orthostatic, and medication-related syncope.6 Recurrence of syncope may be as high as 50% and is not correlated with age or sex.2

Benign causes of syncope predominate in adolescents and young adults. Approximately 30% of athletes who have died during exercise, however, had a prior episode of syncope as a sentinel event.8 Prospective outcome studies in children are lacking, but most reports suggest that mortality rates are extremely low. Significant trauma may result from syncope and can contribute to increased risk of morbidity and mortality, particularly in the elderly.9 The overall U.S. medical cost of syncope is estimated at $2.4 billion annually.10

Pathophysiology

The final common pathway resulting in syncope is dysfunction of either both cerebral hemispheres or the brainstem (reticular activating system), usually from acute hypoperfusion. Reduced blood flow may be regional (cerebral vasoconstriction) or systemic (hypotension).11 Loss of consciousness results in loss of postural tone, with the resulting syncopal episode. Less severe derangements may result in sensations of presyncope or light-headedness. In this fashion, presyncope and syncope may be considered on a continuum with shared etiologies and mechanisms. By definition, syncope is transient; therefore the cause of central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction should likewise be transient.6,12 Persistent causes of significant CNS dysfunction result in coma or depressed consciousness (see Chapter 16).

Diagnostic Approach

The potential causes of syncope are numerous and can be categorized according to their primary mechanism (Box 15-1). The first differential diagnostic consideration is to distinguish syncope from other causes of an apparent sudden loss of consciousness, especially seizure and uncommon disorders such as cataplexy. When syncope is established as the working diagnosis, the life-threatening causes, primarily cardiovascular in origin, are considered first. The principal serious causes of syncope are dysrhythmias and myocardial ischemia.12 Cerebrovascular disease, principally subarachnoid hemorrhage, is less frequently encountered, but equally serious. Toxic-metabolic abnormalities may induce syncope through alterations in blood pressure or cardiac rhythm. Structural cardiac lesions, such as critical aortic stenosis, and sudden interruption of right ventricular outflow by pulmonary embolism can also cause sudden loss of consciousness.12 Dissection of the thoracic aorta rarely manifests primarily as syncope but is potentially catastrophic.

Pivotal Findings

The majority of cases of syncope arise from benign causes, so the evaluation is largely focused on excluding serious pathology. The patient’s history, particularly the setting of the syncope (e.g., postmicturition, venipuncture), patient position (e.g., sitting, standing), prior episodes, and the presence or absence of prodromal symptoms, is central to separating benign from serious causes of the syncopal episode. Young, healthy patients with clearly benign syncope disclosed by a thorough history require little more than a physical examination for anemia or other benign precipitating factors.13–15 The yield of an electrocardiogram (ECG) is generally low; however, it is broadly recommended and has the additional advantages of being noninvasive and relatively inexpensive.13–16 The clinical examination (history and physical examination) alone can suggest the diagnosis in 45% of cases.17 For a large portion of the remainder, however, a clear diagnosis for the syncope may not be established in the ED.17

Symptoms

Symptoms can often suggest the diagnosis, although the relative weight of the history diminishes in older patients and in those not able to remember clearly the events leading up to the loss of consciousness.18 The patient is asked to describe the character of the syncopal event.12 Witnesses may be able to supplement and corroborate the patient’s incomplete recall, and that history should be solicited. Key characteristics include the rate of onset (gradual or abrupt), position on symptom onset (e.g., standing, sitting, or supine), and duration and rate of recovery. Abrupt onset, occurrence while sitting or supine, and duration of more than a few seconds are usually ascribed to serious, often cardiac, causes of syncope, but firm data are lacking. Similarly, incomplete or near-syncope may be less serious, but at least one study suggests that onset associated with a prodrome or presyncope may herald cardiac origin, and thus the prognostic value of this aspect of the history is unsettled.18 The diagnostic approach to presyncope, however, is the same as for syncope.

Additional history regarding the events preceding the syncope is helpful.12 Occurrence during significant exertion suggests outflow obstruction, whereas occurrence after exercise or a prolonged exposure to heat stress suggests orthostasis. The myriad mechanisms that may mediate a neurocardiogenic response, including significant emotional events, micturition, eating, bowel movements, emesis, and movement or manipulation of the neck causing stimulation of the carotid sinus, should be addressed. Occurrence in supine position or the presence of acute palpitations is relatively specific for syncope of cardiac origin.18 Seizures may be preceded by an aura and followed by a typical postictal state.

Events during the syncopal episode do not usually clarify the cause.12 Tonic-clonic movements, related to inadequate cerebral perfusion, can occur in any form of syncope, including benign neurocardiogenic syncope, and should be differentiated from the prolonged activity with subsequent postictal depression of consciousness seen in seizure disorders (see Chapter 102). Trauma from a fall or other mechanism may distract the examiner from evaluating for the underlying syncope that caused the injury.9

The past medical history is critical in stratifying risk.4,7,18 Congestive heart failure is a key determinant of increased short- and long-term mortality in the setting of syncope.4,7,10,14–16 Prior coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and other significant chronic disease also appear to increase the risk of mortality after syncope.5,10

Certain medications are well established to be associated with syncope (Box 15-2). QT interval–prolonging agents, beta-blockers, insulin, and oral hypoglycemics, in particular, deserve attention because of the likelihood of repeated syncope without careful medication monitoring.5

Signs

The physical examination focuses primarily on the elements affecting the cardiovascular and neurologic systems.18 Specific findings are detailed in Table 15-1. Signs of orthostasis should be sought in all cases in which this mechanism is suggested.19 Carotid massage is both safe and occasionally revealing; it is indicated in cases in which the history is suggestive of carotid sinus hypersensitivity.10,14,15 Rectal examination for gross blood or melena is recommended if anemia or gastrointestinal hemorrhage is suspected.

Table 15-1

Directed Physical Examination in Syncope

| SYSTEM | PIVOTAL FINDING | SIGNIFICANCE |

| Vital signs | Pulse rate and rhythm | Tachycardia, bradycardia, other dysrhythmias |

| Respiratory rate and depth | Tachypnea suggests hypoxia, hyperventilation, or pulmonary embolus | |

| Blood pressure | Shock may cause decreased cerebral perfusion; hypovolemia or medication use may lead to orthostasis | |

| Temperature | Fever from sepsis may cause volume depletion and orthostasis | |

| Skin | Color, diaphoresis | Signs of decreased organ perfusion |

| HEENT | Tenderness and deformity | Signs of trauma |

| Papilledema | Increased intracranial pressure, head injury | |

| Breath | Ketones from ketoacidosis | |

| Neck | Bruits | Identify presence of cerebrovascular disease |

| Jugular venous distention | Right-sided heart failure from myocardial ischemia, tamponade, pulmonary embolism | |

| Lungs | Breath sounds, crackles, wheezes | Infection, left-sided heart failure from myocardial ischemia, rarely pulmonary embolism |

| Heart | Systolic murmur | Aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Rub | Pericarditis, tamponade | |

| Abdomen | Pulsatile mass | Abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Rectum | Stool for gross blood or melena | Anemia, gastrointestinal bleed |

| Pelvis | Uterine bleeding, adnexal tenderness | Anemia, ectopic pregnancy, hypovolemia |

| Extremities | Pulse equality in upper extremities | Subclavian steal, thoracic aortic dissection |

| Neurologic | Mental status, focal neurologic findings | Seizure, stroke, or other primary neurologic disease |

Ancillary Studies

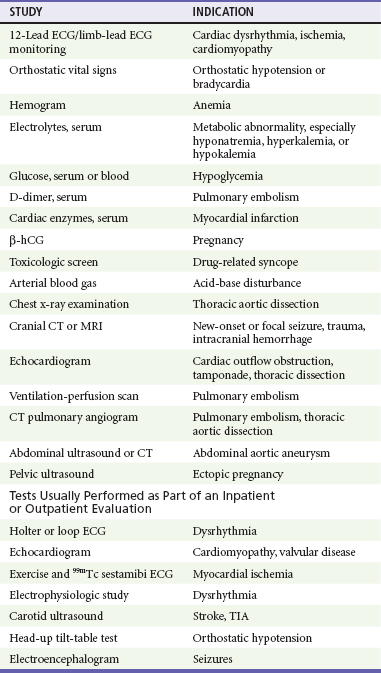

The chief diagnostic adjunct in evaluating syncope is the 12-lead ECG (Table 15-2). It is warranted in all cases of syncope except in young, otherwise healthy patients with a clear history and setting for benign neurocardiogenic (vasovagal) syncope.10,14,15 Dysrhythmias and shortened PR or prolonged QT intervals may be identified on the 12-lead ECG. A right bundle branch block in association with ST elevation in leads V1 through V3 suggests Brugada’s syndrome.20 Unanticipated cardiac hypertrophy may be revealed. Continuous limb-lead ECG monitoring in the ED may also identify transient dysrhythmias. An ECG showing right ventricular strain pattern may suggest pulmonary embolism, whereas diffuse ST elevation or electrical alternans helps diagnose pericarditis associated with pericardial tamponade.

Table 15-2

Routine hematologic and urine studies have limited usefulness in the evaluation of syncope and are generally not indicated.21 When suggested by the history and physical examination findings, however, selective use of the hemogram, serum electrolytes and glucose, urine drug screen, and pregnancy test may identify or exclude some uncommon causes of syncope (see Table 15-2). Chest radiography and serum B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) testing are warranted if heart failure is suspected or known by history. Other than seizure or intracranial hemorrhage, primary neurologic events rarely are the cause of syncope. Cranial computed tomography is indicated only when intracerebral hemorrhage is suspected on the basis of sudden syncope with accompanying headache, particularly of sudden onset, or in the presence of abnormalities on neurologic examination.22

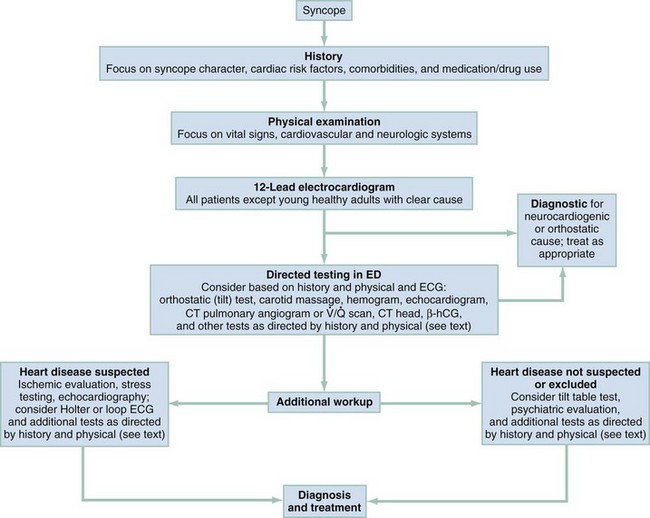

In otherwise healthy patients in whom a benign dysrhythmia, such as episodic supraventricular tachycardia or atrial fibrillation, is suspected, Holter or event ECG monitoring may be helpful. In patients with significant underlying cardiac disease or when a significant dysrhythmia is a possible cause of the syncope, echocardiography, continuous monitoring, or cardiovascular stress testing may be helpful in the inpatient or ED observation unit setting. Depending on the results of initial evaluation, electrophysiologic studies or magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Electroencephalography is useful only when a seizure episode is suspected. Tilt table testing, although infrequently used in the United States, may have diagnostic value in elderly patients and children in whom chronic orthostatic hypotension is possible.15 Orthostatic vital signs, although unreliable in evaluation of volume status, may be helpful when positional changes are accompanied by typical presyncopal symptoms and a significant rise in heart rate or fall in blood pressure.19,21 A schematic of selected diagnostic testing strategies for syncope is depicted in Figure 15-1.

Figure 15-1 Management algorithm for patients with syncope.

Diagnostic Algorithm

The critical diagnoses to consider are listed in Table 15-3.

Table 15-3

The emergent causes of syncope are protean and are included in Box 15-1. Many other causes such as neurocardiogenic and reflex-mediated syncope have benign mechanisms.

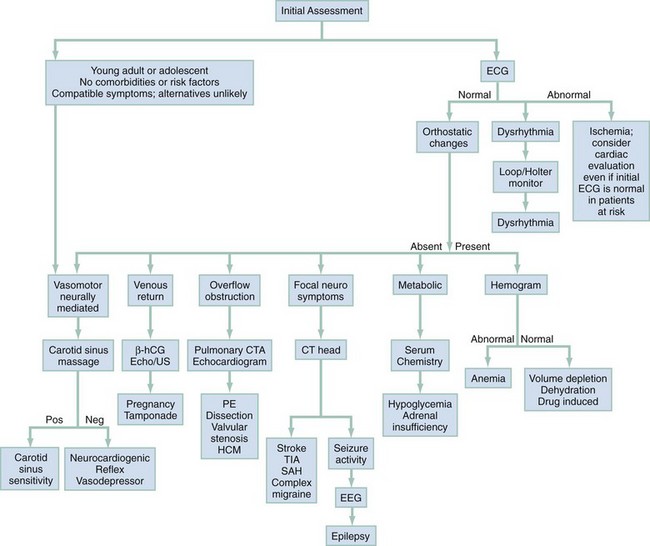

After stabilization and assessment, the clinical features coupled with onset and recovery can suggest the cause (Table 15-4). A logical approach to the history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing is depicted in Figure 15-2. The emphasis is on risk stratification because short-term mortality risk in syncope is related to structural cardiac disease, heart failure, and dysrhythmias.23

Table 15-4

Clinical Features of Common and Serious Causes of Syncope

| CAUSE | ONSET AND RECOVERY | FEATURES |

| Dysrhythmia | Classically abrupt onset and rapid recovery | Classic presentation uncommon; past cardiac history, risk factors for CAD more common in elderly; implanted pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator |

| Cardiac outflow obstruction | Exertion causes abrupt symptoms; rapid recovery with rest | Murmurs not always audible; mechanical valves warrant close monitoring |

| Myocardial infarction | Exertion or at rest; recovery often incomplete with chest pain persisting | Past cardiac history, risk factors for CAD; chest pain and shortness of breath common but frequently absent in diabetics and the elderly |

| Pulmonary embolism | Abrupt onset; recovery often incomplete with dyspnea persisting | Chest pain, dyspnea, hypercoagulable state, DVT, pregnancy |

| Thoracic aortic dissection | Spontaneous; recovery often incomplete with chest or upper back pain persisting | Tearing chest pain; associated with hypertension, Marfan syndrome, cystic medial necrosis |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Spontaneous onset; recovery often incomplete with abdominal pain persisting | Abdominal or low back pain; associated with peripheral vascular disease |

| Pericardial tamponade | Penetrating chest trauma or thoracic cancers | Beck’s triad of hypotension, JVD, muffled heart sounds |

| Anomalous left coronary artery | Onset with exercise, Valsalva maneuver | Left coronary artery arises from pulmonary artery; usually detected in childhood |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | Rapid onset; sentinel event may resolve | Focal neurologic findings; “thunderclap” worst headache; nuchal rigidity |

| Vertebrobasilar insufficiency | Posture change or neck movement | Vertigo, nausea, dysphagia, dysarthria, blurry vision common associated symptoms |

| Hypovolemia | Bleeding, emesis, heat stress, dehydration; gradual onset | Orthostatic hypotension |

| Anemia | Bleeding, often occult or gradual from menses or gastrointestinal sources; iron deficiency or decreased red blood cell production | Orthostatic hypotension commonly associated |

| Hypoglycemia | Gradual onset; incomplete spontaneous recovery common | Diabetes, ingestion or injection of hypoglycemics or insulin; diaphoresis, anxiety, jitteriness |

| Hypoxemia | Usually gradual onset; spontaneous recovery if asphyxiating circumstance is reversed | Carbon monoxide, natural gas, sewer gas, bleach-ammonia mix |

| Subdural hematoma | Onset with or after trauma (which may be trivial in high-risk patients) | Elderly, alcoholics, patients on anticoagulants at greater risk |

| Air embolus | Diving | Hyperbaric oxygen a key treatment |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Associated with myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolus | Risk factors for myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism |

| Drug syncope | Medication associated with syncope | Consider illicit and alternative drug use; elderly at risk for polypharmacy and drug interactions |

| Ruptured ectopic pregnancy | Patient often unaware of pregnancy | Abdominal pain, abnormal tenderness; positive β-hCG test |

| Seizure | Abrupt or with aura; postictal state common | Past history common |

| Carotid sinus sensitivity | Carotid sinus sensitivity; rapid onset and recovery | Shaving, necktie, sudden neck movement; carotid massage may provoke symptoms |

| Reflex syncope | Gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or thoracic stimulation | Urination, defecation, cough, eating, swallowing, weightlifting |

| Neurocardiogenic (vasovagal) | Emotion, pain are common triggers; upright posture; gradual onset; rapid recovery once supine | Prodrome of light-headedness, graying or blurring of vision, nausea, sweats common |

| Hyperventilation | Emotion, pain; gradual onset; patient often unaware of rapid respirations | Perioral tingling, carpopedal spasms, extremity numbness |

| Narcolepsy | Often spontaneous | Known history |

| Basilar artery migraine | Specific triggers often known to patient | Visual prodrome often absent; more common in young women; vertigo and nausea common |

| Trigeminal or glossopharyngeal neuralgia | Sudden onset; specific triggers often known to patient | Lancinating pain in characteristic location |

| Subclavian steal | Moving affected arm | Thoracic outlet syndrome |

| Psychogenic | Variable | Anxiety or psychiatric history; diagnosis by examining symptom pattern and excluding organic cause |

| Breath-holding | Deliberate breath-holding | Usually toddlers or young children |

| Drop attack | Unpredictable | Not true syncope—no loss of consciousness; usually elderly; loss of tone, ataxia, vertigo |

Figure 15-2 Diagnosis algorithm for syncope.

Empirical Management

Several scoring systems have been proposed as aids in the admission decision-making process, most notably the San Francisco Syncope Rule.24 In essence, this guideline suggests that in the absence of abnormal ECG findings, shortness of breath, hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg), anemia (hematocrit <30%), or a history of heart failure, the patient is at sufficiently low risk for outpatient disposition to be considered. The safety and efficacy of the San Francisco Syncope Rule as well as other proposed rules, however, have not been established, and routine application cannot yet be recommeded.4,7,25–29

Hospitalization is required for patients with chest pain, unexplained shortness of breath, a history of significant congestive heart failure, or valvular disease.12,16,29 Patients with ECG evidence of ventricular dysrhythmias, ischemia, significantly prolonged QT interval, or new bundle branch block are also admitted.12,15,16,30 The clinician should consider monitoring patients with any of the following indications: age older than 45 years, preexisting cardiovascular or congenital heart disease, family history of sudden death, serious comorbidities such as diabetes, or exertional syncope.15,16,21,31

The ED evaluation of syncope is often inconclusive. After a history, physical examination, and 12-lead ECG, up to 50% of patients do not have a firm diagnosis.17,31 Patients younger than 45 years and without worrisome symptoms, signs, or ECG findings are generally at very low risk for adverse outcome and may often be treated as outpatients. Discharged patients should be warned of the hazards of recurrent syncope occurring during activities such as driving or working at heights.15

References

1. Thijs, RD, et al. Unconscious confusion—a literature search for definitions of syncope and related disorders. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:35.

2. Chen, LY, Shen, WK, Mahoney, DW, Jacobsen, SJ, Rodeheffer, RJ. Prevalence of syncope in population aged more than 45 years. Am J Med. 2006;119:1088.

3. Sun, BC, Emond, JA, Camargo, CA, Jr. Characteristics and admission patterns of patients presenting with syncope to U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1029.

4. Colivicchi, F, et al. Development and prospective validation of a risk stratification system for patients with syncope in the emergency department: The OESIL risk score. Eur Heart J. 2004;24:811.

5. Chen, L, et al. Risk factors for syncope in a community-based sample (the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol. 1999;85:1189.

6. Soteriades, ES, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:878.

7. Kessler, C, Tristano, J, De Lorenzo, RA. The emergency department approach to syncope: Evidence-based guidelines and prediction rules. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:487.

8. Maron, BJ, Epstein, SE, Roberts, WC. Causes of sudden death in competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:204.

9. Rubenstein, LZ, Josephson, KR. The epidemiology of falls and syncope. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:141.

10. Smars, PA, Decker, WW, Shen, WK. Syncope evaluation in the emergency department. Curr Opinion Cardiol. 2007;22:44.

11. Folino, FA. Cerebral autoregulation and syncope. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;50:49.

12. Kapoor, WN. Syncope. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1856.

13. Sun, BC, et al. Low diagnostic yield of electrocardiogram testing in younger patients with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:240.

14. Strickberger, SA, et al. American Heart Association, Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Rhythm Society: AHA/ACCF scientific statement on the evaluation of syncope. Circulation. 2006;13:316.

15. Brignole, M, et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope—update 2004. Europace. 2005;6:467.

16. Huff, JS, et al. Clinical policy: Critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:431.

17. Linzer, M, et al. Diagnosing syncope. Part 1: Value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:989.

18. Alboni, P, et al. Diagnostic value of history in patients with syncope with or without heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1921.

19. Sarasin, FP, et al. Prevalence of orthostatic hypotension among patients presenting with syncope in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:497.

20. Dovgalyuk, J, Holstege, C, Mattu, A, Brady, WJ. The electrocardiogram in the patient with syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:688.

21. Meyer, MD, Handler, J. Evaluation of the patient with syncope: An evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:189.

22. Goyal, N, et al. The utility of head computed tomography in the emergency department evaluation of syncope. Intern Emerg Med. 2006;2:148.

23. Reed, MJ, Gray, A. Collapse query cause: The management of adult syncope in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:589.

24. Quinn, JV, et al. Derivation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with short-term serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:224.

25. Quinn, J, McDermott, D, Stiell, I, Kohn, M, Wells, G. Prospective validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:448.

26. Sun, BC, et al. External validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:420.

27. Serrano, LA, et al. Accuracy and quality of clinical decision rules for syncope in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:362.

28. Birnbaum, A, Esses, D, Bijur, P, Wollowitz, A, Gallagher, EJ. Failure to validate the San Francisco Syncope Rule in an independent emergency department population. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:151.

29. Reed, MJ, et al. The Risk stratification Of Syncope in the Emergency department (ROSE) pilot study: A comparison of existing syncope guidelines. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:270.

30. Sarasin, FP, et al. A risk score to predict arrhythmias in patients with unexplained syncope. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1312.

31. Costantino, G, et al. Short- and long-term prognosis of syncope, risk factors, and role of hospital admission: Results from the STePS (Short-Term Prognosis of Syncope) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:276.