64 Syncope

• Syncope is a symptom, not a diagnosis.

• Patients with cardiac syncope have a 6-month mortality rate in excess of 10%.

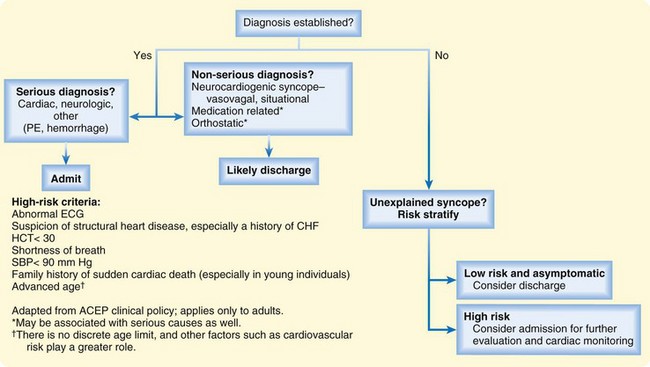

• If the diagnosis can be made, the disposition will be based on that diagnosis.

• When the patient’s symptoms have resolved and the cause is unclear, risk stratification can help in making decisions on disposition.

• Risk factors in emergency department patients include abnormal electrocardiographic findings, including any rhythm abnormalities detected during monitoring. Other risk factors include a history of cardiac disease (especially congestive heart failure) and absence of a prodrome, which places patients at risk for unfavorable cardiac outcomes. Those with persistently abnormal vital signs, shortness of breath, or a low hematocrit are also at higher risk for other adverse outcomes.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that 1 in 4 people will faint during their lifetime and that 6 in 1000 people per year will suffer from the symptom of syncope. Syncope is responsible for 1% to 2% of all emergency department (ED) visits, and the cost of hospitalization for syncope approaches $2 billion annually.1–4

Pathophysiology

Syncope comes from the Greek word synkoptein, meaning “to cut short.” Hippocrates was the first to use the term and describe the symptom.5 Syncope has many causes, but the pathophysiology of the final pathway is the same: hypoperfusion of the cerebral cortex and reticular activating system, which after 8 to 10 seconds of interrupted perfusion causes loss of consciousness; a shorter period results in lightheadedness or dizziness and is referred to as near syncope.

Classification of Syncope

The American College of Physicians lists four major prognostic categories of syncope: neurally mediated, orthostatic, neurogenic, and cardiac; actually, a fifth category (“syncope of unknown cause”) is recognized because in most cases the cause of the syncope remains unknown even after extensive investigation.6,7

Neurally Mediated Syncope

Neurally mediated syncope is syncope associated with inappropriate vasodilation, bradycardia, or both as a result of inappropriate vagal or sympathetic tone.8 It is a benign type of cardiovascular syncope that is often associated with a sensation of increased warmth and may be accompanied by preceding lightheadedness (prodrome) along with sweating and nausea. A slow, progressive onset suggests the subcategory vasovagal syncope. Sweating and nausea do not occur with orthostatic hypotension, which is another cause of syncope preceded by lightheadedness.5

Orthostatic Syncope

Orthostatic syncope occurs in individuals with documented postural hypotension associated with syncope or symptoms of presyncope.4 In cases of orthostatic syncope, measurement of blood pressure is recommended, first after the patient is supine for 5 minutes and then after the patient is able to stand for 1 to 3 minutes. A decrease of more than 20 mm Hg in systolic pressure is considered abnormal, as is a drop in pressure below 90 mm Hg independent of the development of symptoms.9

Because orthostatic hypotension occurs in asymptomatic individuals, vital signs are neither particularly sensitive nor specific. In fact, positive orthostatic changes have been documented in up to 40% of asymptomatic patients older than 70 years and in 25% of those younger than 60 years. Similarly, a notable number of children who are asymptomatic have been documented to have orthostatic hypotension.5,10

The most common cause of orthostatic syncope is intravascular volume loss, which may be due to dehydration or bleeding. Orthostatic syncope is not always benign because many patients with serious causes can have this symptom.11

Neurologic Syncope

Most cases involving neurologic causes of syncope are easily predicted. In general, when these patients have symptoms suggesting a specific disease process, the need for intervention based on neurologic symptoms is usually obvious. It is not recommended that a routine neurologic work-up be performed in all patients with syncope unless related neurologic symptoms are present. It has been determined that routine neurologic testing and investigation, such as computed tomography (CT), is not cost-effective in patients without neurologic symptoms.12

Cardiac-Related Syncope

Cardiac-related syncope is clearly the most dangerous class of syncope, and it can be a harbinger of sudden death. Because patients with documented cardiac syncope have a 6-month mortality rate of greater than 10%, timely and thorough evaluation is warranted.13

Syncope of Unknown Cause

Syncope of unknown cause is the largest category of syncope, with estimates as high as 40%, even with extensive work-up.1 Some studies have found that after evaluation in the ED, physicians are uncertain of the cause of the syncope more than 50% of the time.14 As a result, many serious cases are initially classified in this category, which causes a dilemma for emergency physicians who must decide whether to admit or discharge these patients. It is this largest group of patients who present the greatest challenge for physicians.

Recommended Diagnostic Tests

Ongoing or related symptoms associated with syncope should direct the ED investigation. CT is not indicated for all patients, but one should not ignore associated symptoms, for which a complete work-up should be performed7 (e.g., CT in patients with associated headache or abdominal pain, urine pregnancy tests in females, ultrasonography in pregnant women, troponin assay and CT angiography in patients with chest pain and dyspnea).

A routine electrocardiogram (ECG) is almost always indicated, as are rhythm strips and monitoring while the patient is in the ED. Any nonsinus rhythms or new changes on the ECG should be a concern. Routine basic laboratory tests in asymptomatic patients are not recommended, and their use should be guided by the history and physical examination. Recent work has focused on the value of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a predictor of risk in patients with syncope.15 BNP may have some utility but requires further consideration before becoming a recommended test. In particular, the value of a single reading and the timing of drawing blood in relation to the event require further work. In addition, although it makes sense that BNP may be helpful because it is a predictor of congestive heart failure (CHF) and structural heart disease, it remains unclear whether it provides any greater value over taking a good history, especially given the added cost of the test.16

Prognosis

Perhaps the best investigation of the prognosis of patients with syncope was done by Soteriades et al., who used data from the Framingham study.13 This study assessed the risk for death in a prospective cohort of 7814 patients over a 17-year period. The results were dramatic. Those with documented heart disease and syncope had twice the mortality rate of patients without syncope, and patients with syncope with a neurologic cause were 50% more likely to die. People with syncope of unknown cause also had a significantly increased risk for death of 30%, whereas those with neurally mediated (vasovagal) syncope had a lower risk. The study clearly shows that the increased risk for death in this group requires further scrutiny, as does ED disposition and management.

The absence of cardiac symptoms is not reassuring because patients can have serious “silent symptoms” (silent myocardial infarction and silent arrhythmia, such as Brugada syndrome17) that may not be obviously associated with syncope on initial evaluation. Such patients may not have a history of cardiac disease, and syncope may be the first symptom. Patients with cardiac symptoms and syncope clearly need thorough and timely evaluation and thus in most cases require emergency hospitalization.18

1. Is the syncope a symptom indicating that known underlying heart disease is active, unstable, and related to the episode?

2. Is the syncope a symptom of occult underlying heart disease?

3. Is the syncope a symptom of an occult noncardiac life-threatening process (e.g., pulmonary embolism, occult bleeding, transient ischemic attack, subarachnoid hemorrhage)?

To maximize the sensitivity of detecting underlying disease, physicians frequently admit low-risk patients for further evaluation, although the cost-effectiveness and value of such decisions are often questioned.19 It is this group of asymptomatic patients with syncope who are most likely to benefit from risk stratification strategies to guide disposition decisions.

Acute Risk Stratification in the Emergency Department

Martin et al. developed the first risk stratification scheme for patients evaluated in the ED for syncope.20 The stratification was premised on 1-year prognosis for death or cardiac morbidity. Four predictors of death at 1 year were found: age older than 45 years, history of ventricular dysrhythmias, history of CHF, and abnormal findings on an ECG. A similar study found that an abnormal ECG and history of structural heart disease (primarily CHF) predicted mortality but that a much higher age cutoff (older than 65 years) could predict death at 1 year.3

Sarasin et al. developed a risk score for ED patients with syncope.21 The score was based on three factors associated with increased risk for an arrhythmia: abnormal findings on an ECG, age older than 65 years, and a history of any cardiac disease (primarily CHF).

Finally, Quinn et al. derived and validated a decision rule that addresses short-term risk (7 days) to better determine immediate risk in patients in the ED.2,22 Again, a history of CHF and abnormal findings on an ECG were the most important predictors. The decision rule considered all patients with syncope and also determined that shortness of breath, hematocrit higher than 30, and systolic blood pressure greater than 90 mm Hg were important risk factors. Age older than 75 years was found to be sensitive but nonspecific in this cohort and not useful as a predictor.

Others have tried to validate this work with variable success.23–25 The key to studies being able to most closely validate the work is using the proper ECG definition, which includes not only new changes on the ECG but also any nonsinus rhythms that are found not only on the ECG but also during monitoring throughout the patient’s ED stay.26

Other important prospective risk stratification studies are from Italy. The OESIL study found that age older than 65 years, history of cardiovascular disease, syncope without a prodrome, and ECG abnormalities were risk factors.3 The EGSYS study found an abnormal ECG, history of heart disease, absence of a prodrome, supine status, palpitations, and effort-related syncope to be risk factors.27 Finally, the STePS study found ECG abnormalities, concomitant trauma, absence of a prodrome, and male gender to be short-term risks.28

Age as a risk factor deserves specific mention because physicians often admit patients with syncope just because of age. For almost all diseases, older people die sooner than younger people, and health problems in general increase with age. Recommending that all people older than 45 years (or even those older than 65 or 75 years) be admitted because this factor predicts 1-year death is impractical. Although it may be sensitive as a predictor, age by itself is a poor discriminator; many younger people have significant illness that puts them at even greater risk. This was demonstrated in a study of the short-term outcomes of asymptomatic patients who had syncope of unknown cause and were older than 50 years; all had benign outcomes.14 Furthermore, comparison of age solely as a risk versus other risk factors has shown that risk factors perform better than age alone.29

Improved Diagnostic Strategies in the Emergency Department

Some investigators have reported that diagnostic and prognostic ability improve with more invasive testing such as echocardiography. This makes sense in that this procedure may identify patients with structural heart disease and a limited ejection fraction; however, another study found that patients who would benefit from echocardiography could be identified by their history and physical examination and that this procedure may not be cost-effective.30 Another group in the United Kingdom found that risk stratification could be improved by implementing a protocol of more aggressive strategies such as tilt-table testing and echocardiography but noted that such strategies may not be cost-effective or practical in the ED.31 An Italian group thought that diagnosis could be improved just with more aggressive history taking and physical examination.32

Because echocardiography and other invasive tests are not routinely available in the ED 24 hours per day, investigators have started to use observation units to avoid inpatient admission for a select group of intermediate-risk patients evaluated in the ED.33 There appears to be some promise for syncope observation units, with the goal being to move more low- and intermediate-risk syncope patients from the traditional inpatient work-up to a more structured and efficient observation or outpatient work-up.

Guidelines for Admission and Disposition

Many specialty societies have devised consensus guidelines for admission to the hospital that have focused on the best available data.34,35 The American College of Emergency Physicians recommends that patients with evidence of cardiac and neurologic causes of syncope, as well as other serious outcomes diagnosed in the ED, be admitted to the hospital. Admission is also recommended for patients with undifferentiated syncope who have risk factors for adverse outcomes (Fig. 64.1).

1 Kapoor WN, Karpf M, Wieand S, et al. A prospective evaluation and follow-up of patients with syncope. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:197–204.

2 Quinn JV, Stiell IG, McDermott DA, et al. Derivation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with short-term serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:224–232.

3 Colivicchi F, Ammirati F, Melina D, et al. Development and prospective validation of a risk stratification system for patients with syncope in the emergency department: the OESIL risk score. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:811–819.

4 Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA, Jr. Direct medical costs of syncope-related hospitalizations in the United States. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:668–671.

5 Grubb BP, Jorge Sdo C. A review of the classification, diagnosis, and management of autonomic dysfunction syndromes associated with orthostatic intolerance. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2000;74:537–555.

6 Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NA, 3rd., et al. Diagnosing syncope. Part 2: unexplained syncope. Clinical efficacy assessment project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:76–86.

7 Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NA, 3rd., et al. Diagnosing syncope. Part 1: value of history, physical examination, and electrocardiography. Clinical efficacy assessment project of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:989–996.

8 Boehm KE, Morris EJ, Kip KT, et al. Diagnosis and management of neurally mediated syncope and related conditions in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28:2–9.

9 Grubb BP, Kosinski DJ, Kanjwal Y. Orthostatic hypotension: causes, classification, and treatment. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:892–901.

10 Atkins D, Hanusa B, Sefcik T, et al. Syncope and orthostatic hypotension. Am J Med. 1991;91:179–185.

11 Sarasin FP, Louis-Simonet M, Carballo D, et al. Prevalence of orthostatic hypotension among patients presenting with syncope in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:497–501.

12 Eagle K, Black H. The impact of diagnostic tests in evaluating patients with syncope. Yale J Biol Med. 1983;56:1–8.

13 Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, et al. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:878–885.

14 Morag RM, Murdock LF, Khan ZA, et al. Do patients with a negative emergency department evaluation for syncope require hospital admission? J Emerg Med. 2004;27:339–343.

15 Reed MJ, Newby DE, Coull AJ, et al. The ROSE (Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:713–721.

16 Costantino G, Solbiati M, Pisano G, et al. NT-pro-BNP for differential diagnosis in patients with syncope. Int J Cardiol. 2009;137:298–299. author reply 299

17 Juang JM, Huang SK. Brugada syndrome—an under-recognized electrical disease in patients with sudden cardiac death. Cardiology. 2004;101:157–169.

18 Oh JH, Hanusa BH, Kapoor WN. Do symptoms predict cardiac arrhythmias and mortality in patients with syncope? Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:375–380.

19 Quinn JV, Stiell IG, McDermott DA, et al. The San Francisco Syncope Rule vs physician judgment and decision making. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:782–786.

20 Martin TP, Hanusa BH, Kapoor WN. Risk stratification of patients with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:459–466.

21 Sarasin FP, Hanusa BH, Perneger T, et al. A risk score to predict arrhythmias in patients with unexplained syncope. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1312–1317.

22 Quinn J, McDermott D, Stiell I, et al. Prospective validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:448–454.

23 Sun BC, Mangione CM, Merchant G, et al. External validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:420–427. 427.e1–4

24 Birnbaum A, Esses D, Bijur P, et al. Failure to validate the San Francisco Syncope Rule in an independent emergency department population. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:151–159.

25 Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Hess EP, Alreesi A, et al. External validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule in the Canadian setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:464–472.

26 Quinn J, McDermott D. ECG criteria of the San Francisco Syncope Rule. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:72–73. author reply 73

27 Del Rosso A, Ungar A, Maggi R, et al. Clinical predictors of cardiac syncope at initial evaluation in patients referred urgently to a general hospital: the EGSYS score. Heart. 2008;94:1620–1626.

28 Costantino G, Perego F, Dipaola F, et al. Short- and long-term prognosis of syncope, risk factors, and role of hospital admission: results from the STePS (Short-Term Prognosis of Syncope) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:276–283.

29 Quinn J, McDermott D, Kramer N, et al. Death after emergency department visits for syncope: how common and can it be predicted? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:585–590.

30 Sarasin FP, Junod AF, Carballo D, et al. Role of echocardiography in the evaluation of syncope: a prospective study. Heart. 2002;88:363–367.

31 Crane SD. Risk stratification of patients with syncope in an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:23–27.

32 Alboni P, Brignole M, Menozzi C, et al. Diagnostic value of history in patients with syncope with or without heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1921–1928.

33 Shen WK, Decker WW, Smars PA, et al. Syncope Evaluation in the Emergency Department Study (SEEDS): a multidisciplinary approach to syncope management. Circulation. 2004;110:3636–3645.

34 Huff JS, Decker WW, Quinn JV, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:431–444.

35 Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt DG, et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope—update 2004. Executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2054–2072.