Symptoms, signs and investigation of urinary tract disorders

Symptoms of urinary tract disease

Symptoms caused by intrinsic disease of the urinary tract

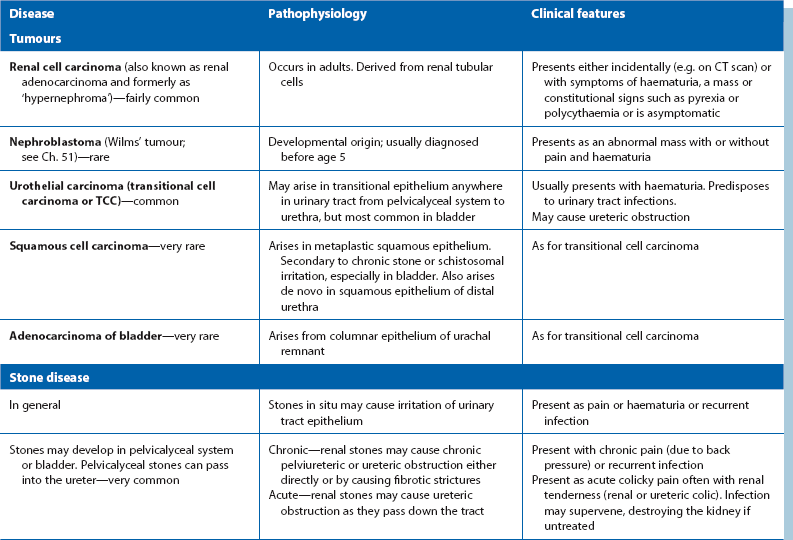

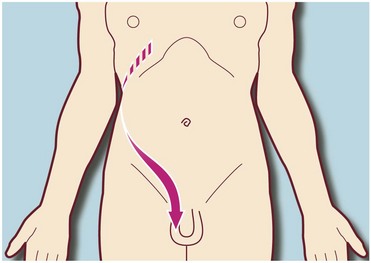

The important urinary tract tumours, stone diseases and infections are outlined in Table 34.1. Any of these may present with haematuria. Disorders which cause urinary stasis also predispose to urinary tract infection.

Congenital abnormalities may involve the kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra and genitalia, either alone or in combination. Most of the serious abnormalities are recognised antenatally by ultrasound, at birth or in early childhood. The exceptions are polycystic disease and medullary sponge kidney, which usually present in adulthood. Less serious congenital abnormalities such as duplex systems may predispose to urinary tract infections because of abnormal flow dynamics. These abnormalities may be discovered at any age during investigation of recurrent urinary infections. Congenital disorders which present mainly in adulthood are discussed in Chapter 39 and those presenting mainly in childhood in Chapter 51.

The common symptoms of urinary tract disease

Abdominal pain

Urinary tract disorders may cause abdominal pain with or without urinary symptoms.

Pain arising from the kidneys and upper tract: Both renal inflammation and stretching of the renal capsule cause pain in the renal angle, the posterior gap between the lowest rib and iliac crest. This area may also become tender to palpation or percussion. Renal stones, tumours or polycystic disease may cause dull and persistent loin pain even without obstruction.

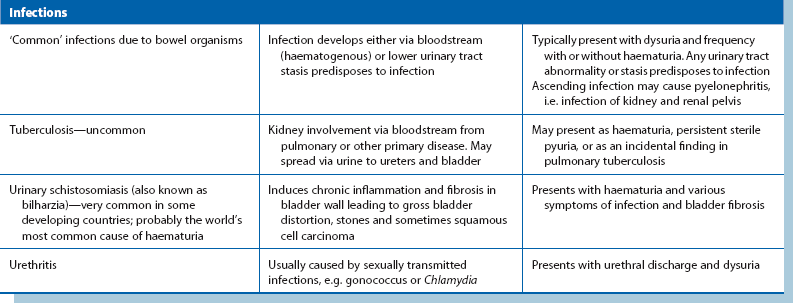

Acute upper ureteric obstruction and distension of the pelvicalyceal system produce excruciating loin pain. The pain is colicky (resulting from powerful ureteric peristalsis) and often radiates to the hypochondrium (right or left upper quadrant of the abdomen) or groin (see Fig. 34.1). This pain is known as renal or ureteric colic. When obstruction is low in the ureter, the pain may radiate to the genitalia.

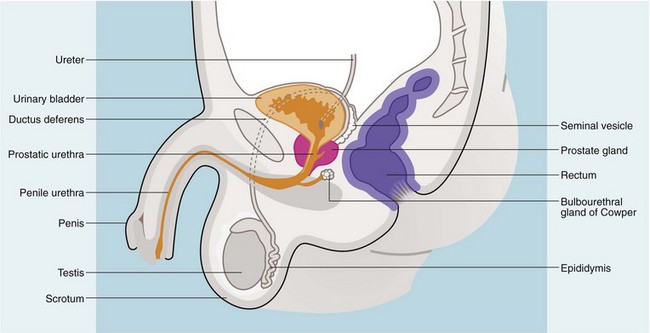

Pain arising from the bladder and lower tract: Pain originating in the bladder (e.g. in cystitis) is experienced in the suprapubic area. Pain may be referred to the penis or vulva if the bladder trigone is involved. In adults, urinary symptoms such as dysuria and frequency are usually present as well, but children may have no localising symptoms or complain only of pain, making the diagnosis less obvious. Dysuria is usually the predominant symptom of urethral disorders, but pain arising in the male urethra (e.g. in sexually transmitted infections) is usually referred to the tip of the penis. Finally, the pain of prostatic inflammation (prostatitis) is usually felt deep in the perineum. The prostate is tender on rectal examination in the acute but not the chronic form.

Pain simulating urinary tract disease: Pain from other abdominal pathology may sometimes mimic pain arising from the urinary tract. Acute appendicitis may present with suprapubic pain, and biliary tract pain may be referred to the right thoracolumbar region, while posterior duodenal ulcers and pancreatic disease may cause pain in the central lumbar region. An expanding or leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm may sometimes mimic urinary tract disease, particularly if a ureter is compressed. Diseases of the thoracolumbar spine, such as metastatic cancer, tuberculosis, spondylosis and disc lesions, may also simulate upper urinary tract disorders. Suspected renal colic with a local rash is usually due to shingles (herpes zoster); the rash may not appear for several days after the onset of pain; perineal zoster may cause retention of urine. In women, pain arising from the ovaries or genital tract (e.g. pelvic inflammatory disease) may be confused with bladder pain.

Disorders of micturition

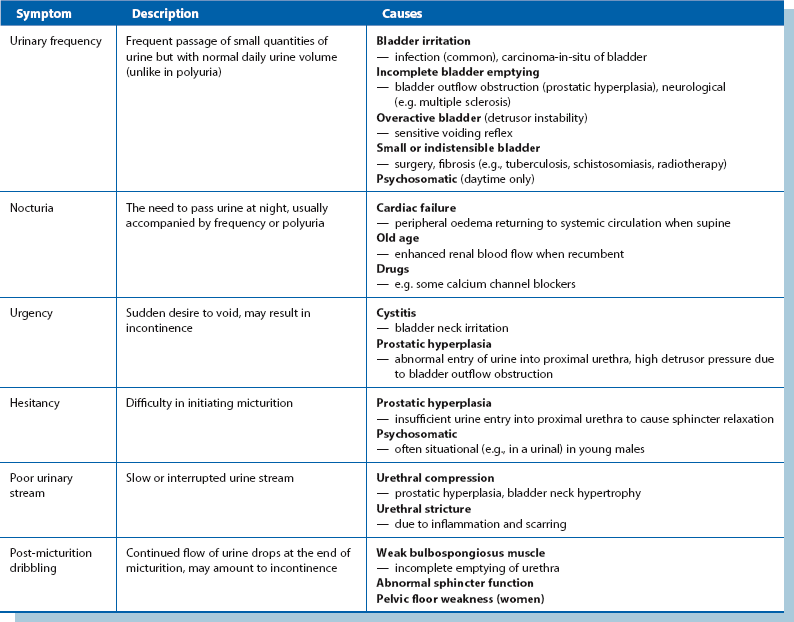

Features and common causes of these symptoms are summarized in Table 34.2.

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS)

This term encompasses the symptoms of hesitancy, poor stream, terminal dribbling and incomplete bladder emptying with frequency, nocturia, urgency and urge incontinence. Although these occur in prostatic obstruction, similar symptoms also occur in bladder neck obstruction, urethral stricture, bladder calculi and lower urinary tract infection. The severity of symptoms can be estimated using the International Prostate Symptom Score (see Box 35.1, p. 446).

Urinary incontinence

The pathophysiology of incontinence can be divided into three categories based on disorders of structure and function which are described below and summed up in Box 34.1. Some disease processes may produce incontinence by more than one mechanism.

Pneumaturia

Pneumaturia is the passage of gas mixed with urine. It is caused by abnormal communication between bowel and urinary tract resulting in fistula formation. The commonest causes are diverticular disease and Crohn’s disease, although it can also occur in carcinoma of the colon or bladder (see Box 34.2). Gross urinary tract infection is inevitable. The patient typically complains of symptoms of urinary infection (dysuria and frequency) and may also describe bubbles or even faeces in the urine.

Approach to the diagnosis of urinary symptoms

Physical examination

Rectal examination

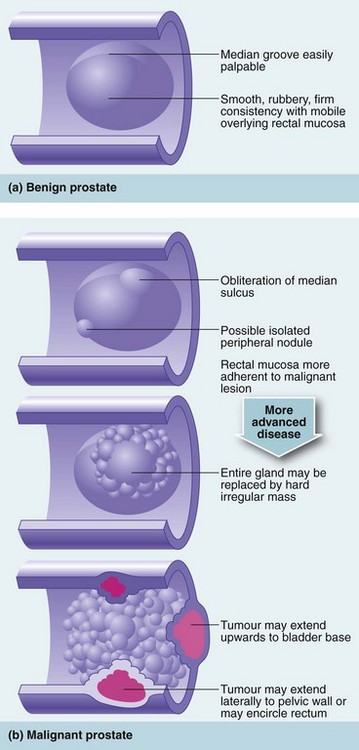

Rectal examination should be performed in both sexes. In females, a vaginal examination may also be indicated. In the male, the prostate is palpated per rectum for size, shape and consistency (Fig. 34.3). The normal prostate is about 3 cm in diameter and weighs 10–15 g; it can be massively enlarged and weigh over several hundred grams, so that its upper edge may be out of reach of the examining finger. Most prostatectomy operations leave a capsular remnant so that the prostate appears palpable after prostatectomy and may be of a firmer consistency.

On palpation, the normal prostate has a smooth surface and a firm consistency and is divided into two lateral lobes by a midline groove. In prostatic hyperplasia, enlargement is usually symmetrical, and the midline groove is maintained. Consistency remains normal. In contrast, a prostate infiltrated with carcinoma is irregular and asymmetrical. There are often hard nodules, and the median groove may be lost. In advanced cases, the tumour may be felt invading laterally into the pelvis or posteriorly around the rectum (see Fig. 34.4). Digital examination can help distinguish benign from malignant prostatic enlargement in gross cases, but if carcinoma is suspected, transrectal ultrasound scanning (TRUS) using a rectal probe is performed, together with multiple needle biopsies under ultrasound guidance. Note, however, that there is a 2% risk of systemic sepsis and the procedure needs to be covered with a short course of antibiotics, e.g. ciprofloxacin. The symptom of prostatic tenderness is uncommon and may indicate prostatitis.

Investigation of suspected urinary tract disease

A simple approach to investigation of urinary tract disease is to consider the following questions:

Are any blood tests likely to be helpful in diagnosis?

Where is the lesion?

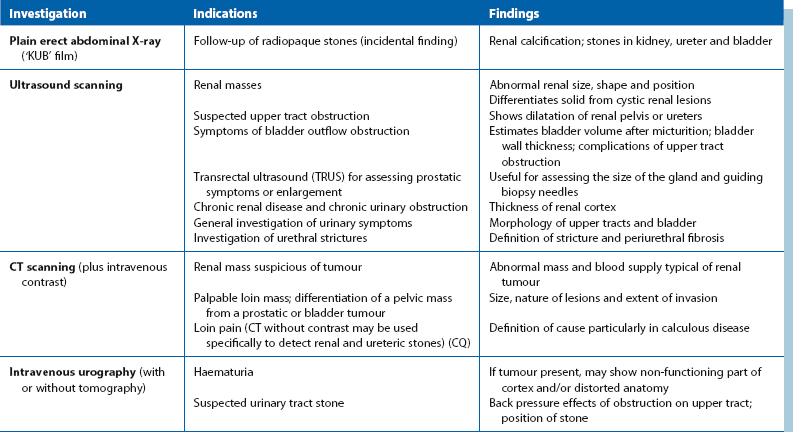

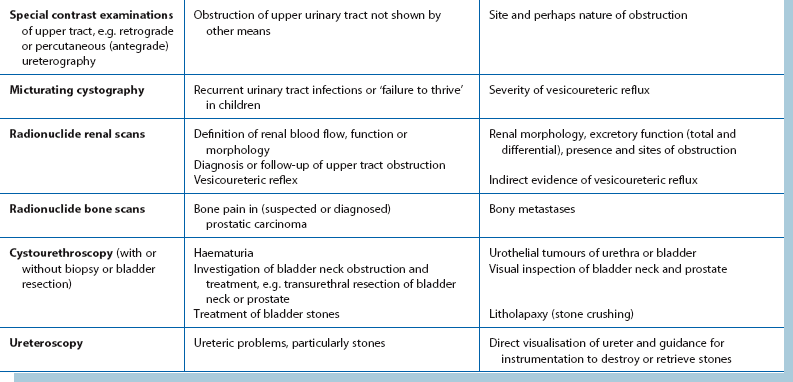

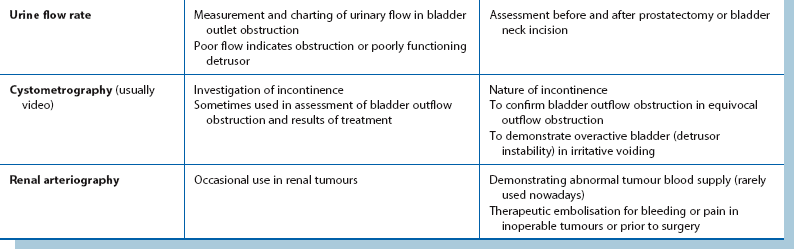

Investigations for localising urinary tract pathology are summarised in Table 34.3.

Suspected upper tract lesions:

Ultrasound: Renal ultrasound is a valuable non-invasive technique for investigating suspected renal masses. It is particularly useful in differentiating solid from cystic lesions and for demonstrating renal pelvis dilatation. If bladder pathology is suspected, the bladder can easily be examined at the same time. The bladder is best seen if it is distended with urine; patients should be advised to drink copious fluids before the investigation. Ultrasound can demonstrate stones in the kidney or bladder even if they are radiolucent (urate), but can rarely demonstrate a stone in the ureter.

CT scanning: Computed tomography (CT) scanning is now the gold standard for imaging the urinary tract, although it provides poor assessment of function. It will also allow assessment of other organs. Modern spiral and multislice CT machines give rapid image capture and better definition; non-contrast CT is indicated for investigation of stone disease, particularly ureteric colic. CT with intravenous contrast helps distinguish renal malignancy from hamartomas and other benign diseases. It can also diagnose the rare angiomyolipoma of the kidney. In renal cell carcinoma, CT can demonstrate direct spread along the renal vein and into the inferior vena cava so that surgery can be better planned. Enlarged lymph nodes may be diagnosed and biopsied percutaneously and the liver examined for metastases. In bladder or prostatic cancer, CT can aid staging by demonstrating whether the disease is organ-confined.

Intravenous urography: In most centres, intravenous urography (IVU) has been superseded by CT for renal tract investigation. IVU involves intravenous injection of a contrast medium which is rapidly filtered by the glomeruli and excreted. This radiopaque solution opacifies the urinary system, demonstrating renal parenchyma, renal pelvis and the ureteric anatomy. The cortical concentration of contrast (nephrogram) gives an indication of the size, shape, thickness and bilateral symmetry of the renal cortex.

Urothelial carcinoma may show as filling defects in the collecting system or bladder. If an abnormality is seen in the kidney or renal pelvis, renal CT is recommended to reveal more detail (see Ch. 5). If renal excretion is poor as in chronic renal failure, IVU yields poor images. In addition, the contrast material may lead to further impairment of renal function. Intravenous contrast is liable to precipitate acute renal failure in diabetic nephropathy. In such cases, retrograde pyelography may be a suitable alternative.

Suspected lower tract lesions:

Radiography and ultrasound: Ultrasound examination is the standard investigation. Modern high-resolution equipment can demonstrate tumours, cysts and other abnormalities of bladder and prostate shape and volume, but can seldom define lesions smaller than 5 mm. Ultrasonography can also define the size, shape and position of stones in the kidney, but is very operator dependent. It can also be used to estimate the bladder residual urine volume in outlet obstruction. Transrectal ultrasound can help assess the size of the prostate, enable directed biopsy of abnormal areas, or help achieve representative biopsies of all areas of the prostate.