Sympathectomy and the management of hyperhidrosis

ASSESSMENT OF HYPERHIDROSIS

Appraise

1. Hyperhidrosis is uncontrolled profuse sweating. It is classified as either local, affecting only specific areas, or general, affecting most parts of the body. It affects up to 2% of the population, and there is probably a genetic predisposition. The axillae are affected in 60% of cases, the palms (often with the feet) in 30%, the head and neck in 10% and the rest of the body, especially under the breasts in females and groins in 5%. Even in localized cases of hyperhidrosis more than one localized area is often affected.

2. It is a social problem. Confirm the diagnosis is of hyperhidrosis (hyper = over + hidros = sweat) and not a complaint of malodour or other dermatological problems such as hydradenitis suppurativa (chronic infection of the apocrine sweat glands). In general those with hyperhidrosis do not have body malodour and the sweat is clear and profuse. Examine each potentially affected area to confirm this.

3. Identify an underlying cause. Primary causes tend to result in generalized rather than localized hyperhidrosis. Endocrine causes include thyroid dysfunction and progesterone/oestrogen imbalance, as occurs with polycystic ovary syndrome or the menopause. Take blood samples on the first consultation. Head injury or the use of certain medications can also produce hyperhidrosis.

4. Determine the severity of the hyperhidrosis by determining specific occasions when hyperhidrosis is a problem. Sweating may occur at a lower than usual ambient temperature and may be precipitated during social confrontation. It is not always necessary to use a social anxiety psychological scoring systems to demonstrate this, but determining the use of avoidance techniques indicates the degree of severity. Axillary sweaters often prefer wearing black or dark tops, doubled so sweat stains do not show. They insert tissues or commercially purchased pads and avoid loose singlets. Palm sweaters may carry a hand-held article to avoid shaking hands on greeting and hold hands only outside in the cold. True plantar sweaters wear loose, regularly replaced shoes, because sweat rots the fabric. Forehead sweaters tend to avoid spicy foods. For research purposes the degree of sweating within a heated ambience can be assessed by the weight increase of applied blotting paper.

5. Arrange a sensitively conducted psychological assessment, clarifying its potential benefits. Emphasize that hyperhidrosis is a life-long problem capable only of alleviation by intervention, not cure.

MANAGEMENT OF HYPERHIDROSIS

1. Aim to treat both the physical and psychological effects. Tailor the range of proffered management to the site, severity, awareness of involved area and perceived severity of disability. Involve the fully informed patient in planning management, fully aware of the implications, actively concurring. Re-discuss the planned treatments and potential side-effects before you embark on a new treatment.

2. Patients with localized hyperhidrosis will usually have tried over-the-counter antiperspirants, often aluminium salt-based. The low pH of these can produce skin irritation, but if they are effective further treatment is not necessary. For primary generalized hyperhidrosis consider oral medications, in particular anticholinergic drugs, such as propantheline or glycopyrrolate (Robinul). After warning of potential anticholinergic side-effects, such as headaches, nausea, urinary hesitancy, blurred vision and palpitations, start with a morning low dose and build up. It is usually best taken in the morning as clients find it is effective for only 4 to 6 hours. Do not normally prescribe it for localized hyperhidrosis except as an adjunctive.

3. Iontophoresis is a ‘home based’ machine method of reducing localized hyperhidrosis. The treatment involves immersing the affected feet or hands area in baths of shallow tap water or placing a wet pad in the axilla. The machine discharges an electronic current through the water which is channelled to the affected area by placing two electrodes in contact with the patient to form a circuit. Iontophoresis can also be used to deliver a chemical through the skin by adding glycopyrolate to the solution. Published results are good, but compliance is often poor, as the bulky machine has to be used regularly. This is time consuming and in practice results are variable.

SUBDERMAL INJECTION OF ATTENUATED BOTULINUS TOXIN (BOTOX)

Appraise

1. subdermal injection of Botox, by its localized anticholinergic action, is very successful at reducing hyperhidrosis. The effect lasts for 6 months as the acetylcholine vesicles regenerate.

2. It is used predominantly to manage axillary hyperhidrosis; its use in palmar or plantar hyperhidrosis often requires a local nerve block as the subdermal injections are uncomfortable. Ensure that you are fully trained in how to deliver ulnar and median blocks: repeated general anaesthesia instead is not appropriate. There is a small risk of infection which could result in palmar fasciitis, and the injections can lead to localized fingertip numbness. Botox injection to the forehead and hairline has some effect on reducing the sensation of facial sweating.

Action

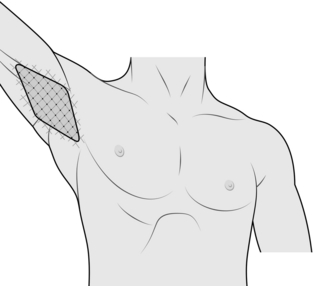

1. Define the area of hyperhidrosis by painting the affected region with iodine and, when dry, sprinkling starch powder over it. The affected area will be a blackened colour. Mark the outer margins of the area and then mark out a 1-cm square grid within it (Fig. 25.1).

2. Ensure that the Botox solution is drawn up beforehand; 4 ml of 2% lidocaine is added to 100 units of Botox and drawn up into four 1-ml syringes with fine needles (as used by insulin-dependent diabetics). Deliver a 0.1 ml dose to the centre of each grid. Work smoothly and quickly over a couple of minutes.

3. The patient is free to leave 30 minutes later after ensuring there are no systemic side-effects, which are rare.

LOCALIZED RETRODERMAL AXILLARY CURETTAGE

Action

1. Make a small skin crease incision less than 0.5 cm in the mid axilla.

2. Through the incision inject about 200 ml of normal saline with 15 ml of 1% lidocaine and adrenaline subdermally, using a long needle and syringe. This tumescence lifts the skin off the under-lying adipose tissue of the axilla.

3. A curette (3 mm) is then passed through the incision just deep to the skin out to the margin of the hairline. With the roughened edge faced upwards and the curette tenting the skin, it is with-drawn towards the incision, abrading the underside of the skin and destroying the subdermal structures. The procedure is repeated in a sweeping fashion clockwise around the incision so that all the hyperhidrosis area is treated. Take time to ensure that all areas are treated and take care not to make the skin too shallow and button-hole it, or pass the curette too deep and damage deeper structures.

4. A steri-strip over the wound is sufficient. Place a gauze swab in the axilla and secure it firmly with wide adhesive tape.

Complications

1. Bruising does occur, but excessive bleeding should not.

2. Small fibrotic bands may be felt in the axilla and look like stretch marks. They usually resolve in 1 month, especially if the area is massaged.

3. Pigmented discoloration of the axillary skin may occur.

4. Localized reduced axillary sensation may persist.

5. Skin loss is rare, and tends to occur at the site where the skin was button-holed during the procedure.

THORACOSCOPIC SYMPATHECTOMY

Appraise

1. The only clear indications for thoracic sympathectomy are localized palm and axillary hyperhidrosis and facial blushing.

2. Other possible indications are rarer and not clearly defined:

Consider thoracoscopic sympathectomy for digital artery vasospastic disorders producing pre-gangrenous skin changes, but only as an adjunctive measure. Severe Raynaud’s-like symptoms (Maurice Raynaud, Parisian physician 1834–1881) result from significant connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma. Treatment is usually by intravenous vasodilators. Digital artery thrombosis secondary to a cervical rib requires rib excision.

Consider thoracoscopic sympathectomy for digital artery vasospastic disorders producing pre-gangrenous skin changes, but only as an adjunctive measure. Severe Raynaud’s-like symptoms (Maurice Raynaud, Parisian physician 1834–1881) result from significant connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma. Treatment is usually by intravenous vasodilators. Digital artery thrombosis secondary to a cervical rib requires rib excision.

Sympathectomy may also benefit patients with post-traumatic pain or causalgia (Greek: kausis = burning + algos = pain) and acrocyanosis (Greek: akron = point, tip + kyanos = blue; blue extremities).

Sympathectomy may also benefit patients with post-traumatic pain or causalgia (Greek: kausis = burning + algos = pain) and acrocyanosis (Greek: akron = point, tip + kyanos = blue; blue extremities).

Angina-like pain from terminal coronary artery branch stenosis in the absence of significant main coronary artery disease is a rare indication for thoracoscopic sympathectomy. Undertake it with caution as it can be technically challenging.

Angina-like pain from terminal coronary artery branch stenosis in the absence of significant main coronary artery disease is a rare indication for thoracoscopic sympathectomy. Undertake it with caution as it can be technically challenging.

3. Although there is a sympathetic innervation to the arteries of the skin and muscle of the limbs, and following sympathetic blockade skin blood flow increases, there is a modest rise only in muscle flow. There is therefore no role for sympathectomy in managing peripheral arterial disease.

4. The sympathetic nervous system is a two neurone system. The cell body of the pre-ganglionic neurone is in the spine cord. Its fibres pass through the ventral roots of the spinal nerves, travel in the sympathetic chain and synapse in the ganglia. The sympathetic ganglia lie in a chain running over the heads of the ribs. Postganglionic fibres from the cell bodies in the ganglia pass to the corresponding spinal nerves to enter the limb in one or other of the major nerve trunks. The sympathetic fibres to the arm synapse in ganglia T2–3 (T2 for the hand and T2 + 3 for the axilla). The upper (T1) ganglion fuses with the inferior cervical ganglion to form the stellate ganglion. Damage to the sympathetic stellate ganglion produces a Horner’s syndrome (Johann Horner, Zurich ophthalmologist 1831–1886, described ptosis – drooping of the eyelid, myosis – contracted pupil, enophthalmos – eyeball recession, and anhydrosis – dry eye).

5. Several approaches to the upper thoracic sympathetic chain have been described including transaxillary and anterior (supraclavicular), but the thoracoscopic method is the only one regularly undertaken.

Prepare

1. Personally obtain fully informed consent, repeating the counselling to plan the procedure and its alternatives. Warn about compensatory sweating, Horner’s syndrome, postoperative pain, the possibility of a chest drain and of conversion to an open procedure and 10% failure rate.

2. Order a preoperative chest X-ray for all patients to exclude any pulmonary disease, which may make the establishment of a pneumothorax difficult.

3. Undertake surgery one side at a time to guard against the small risk of bilateral pneumothorax. Occasionally, unilateral surgery has a bilateral effect. Also, if compensatory sweating follows unilateral operation, the patient can decline surgery on the other side.

Access

1. Perform the procedure under a general anaesthetic. A standard endotracheal tube is almost always sufficient, rather than using a double-lumen tube.

2. Position the patient in a supine position with a small sandbag under the operation side. Bring this side to the edge of the table. Place the arm over the patient’s face, held in place with wool and crepe bandaging onto a right angle bar. This resembles someone lying on a beach guarding his eyes from the sun (Fig. 25.3).

3. Through the mid-axillary line at the base of the axillary hairline, make a small 1-cm incision between ribs 3 and 4.

4. Establish an artificial pneumothorax using a Veress needle inserted through the wound after fully informing the anaesthetist.

5. Slowly insufflate 1 L of carbon dioxide into the pleural space.

6. Through the same 1-cm incision introduce a 10-mm ‘laparoscopic’ port between the ribs. Use an optical port that allows the penetration to be watched under direct vision. Introduce the thoracoscope, usually 0 degrees deflection with a central channel through which to pass instruments. If further access is necessary, insert a 5-mm port below and to one side of the telescope port.

Assess

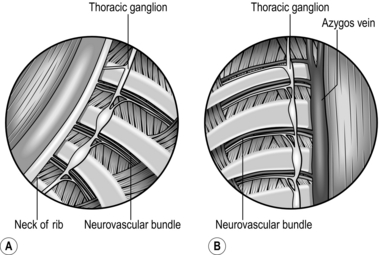

1. Confirm your orientation (Fig. 25.4). Place the scope looking in the top lateral corner, which is a safe area. Make sure the ribs run horizontally. Follow the ribs medially until you see the sympathetic ganglia and chain lying on the necks of the ribs. The highest rib you see on either side is the second, although in the tall, thin patient the first rib may be visible.

2. Ensure the lung is collapsed. If not, slightly raise the insufflation pressure. Wait a few moments while the lung collapses with the patient in a head up position. This position also decompresses any little veins which may run over or near to the rib heads.

3. Carefully divide the occasionally encountered pleural adhesions, exerting minimal traction.

4. Identify the first rib. Ask the anaesthetist to palpate the rib in the supraclavicular fossa. If you see it covered by the palpating finger, avoid operating on the chain at that level so as to avoid creating a Horner’s syndrome.

Action

1. With a blunt (non-diathermy) probe, identify the third rib by tapping it. Identify the ganglia by pushing against them gently with the probe to confirm their soft consistency and glistening surface. If adhesions obscure the view over the third rib, you can easily identify the chain by visualizing the fourth or fifth rib and following the chain superiorly.

2. Identify the lowest and most effective diathermy setting by creating a preliminary burn over the rib away from the nerve and to get ‘under’ the pleura. Lift the pleura up and carefully dissect the third thoracic ganglion free over the rib, using sharp dissection. Having cleanly dissected the nerve over the third rib, divide it under direct vision. Alternatively, use the diathermy hook to lift the chain away from the rib before dividing it with diathermy. Now position the inferior cut end of the chain below the rib to avoid later regeneration of the sympathetic chain.

3. Clipping of the sympathetic chain is possible and is reputed to achieve the same result in both hyperhidrosis and facial flushing. A theoretical advantage is that the clips can be removed later if complicating side-effects are intolerable.

4. If any of the small veins around the chain start to bleed, apply direct pressure with the non-diathermy probe to the pleura over the vessel away from the cut edge. Wait. The bleeding will stop. Now wash the pleural cavity with saline.

5. Place 40 ml of 0.25% marcaine into the pleural cavity.

6. Withdraw the port and thoracoscope to the chest wall. Turn off the insufflation and open the gas inlets, while watching the lung inflating with the assistance of the anaesthetist. Confirm that the fluid in the pleural cavity is a clear small amount of local anaesthetic and not blood stained. Remove the scope as the fully inflated lung confirms no significant pneumothorax.

7. Close the small wounds with a stitch or plastic adhesive strip.

Aftercare

Complications

1. Immediate complications include damage to intrathoracic structures requiring thoracotomy. Pneumothorax, which may be under tension, requires the insertion of a chest drain. Pain is variable, occasionally severe, but usually only discomfort on deep breathing.

2. Delayed complications include failure to resolve symptoms and compensatory sweating. These may develop many years after surgery. Compensatory hyperhidrosis, usually on the chest and back, occurs in 50% of patients. It varies from trivial to devastating. There are no clear markers of who will suffer, but it is more likely in generalized hyperhidrosis patients

The ‘Harlequin’ effect, when half the face blushes and sweats and the other half does not, can be distressing, Usually, if it occurs after bilateral operations, it is not significant.

More rarely, especially if the chain was divided at a high level, the patient complains of nasal congestion and eye lid drooping of a Horner’s syndrome. Thoracoscopic sympathectomy has virtually abolished this complication. The highest rib that can be directly viewed intrapleurally via the thoracoscope is the second rib. If you need to go to a high-placed ganglion, as for facial sweating, avoid using diathermy and employ sharp dissection alone to isolate the ganglion over the neck of the highest, most easily viewed rib. This is safe, and Horner’s syndrome should not occur.

LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY

Appraise

1. This may be carried out as an open operation or non-operatively by injecting phenol into the lumbar chain. A laparoscopic approach has been described but it is difficult to obtain good results. Phenol injection has largely superseded open surgery.

2. The number of lumbar ganglia varies, but there are usually four on each side. The second and third ganglia are removed at operation.

3. Avoid this technique in males because of the risk of causing impotence. Some authors claim that to preserve normal ejaculation the first lumbar ganglion on at least one side must be left intact.

4. The clinical indications for lumbar sympathectomy are vague:

Hyperhidrosis of the feet is cured by lumbar sympathectomy. The procedure is rarely undertaken, but it demands a surgical sympathectomy.

Hyperhidrosis of the feet is cured by lumbar sympathectomy. The procedure is rarely undertaken, but it demands a surgical sympathectomy.

Peripheral vascular disease in patients with non-reconstructable occlusive atherosclerotic disease and thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease – Leo, New York physician 1879–1943). Rest pain or toe dry gangrene may benefit from a chemical sympathectomy. Rest pain is relieved in 60% for up to 3 years, and further benefit may be obtained by repeated phenol injections. There is no improvement in the subsequent amputation rate.

Peripheral vascular disease in patients with non-reconstructable occlusive atherosclerotic disease and thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease – Leo, New York physician 1879–1943). Rest pain or toe dry gangrene may benefit from a chemical sympathectomy. Rest pain is relieved in 60% for up to 3 years, and further benefit may be obtained by repeated phenol injections. There is no improvement in the subsequent amputation rate.

Raynaud’s syndrome. Lumbar sympathectomy may be a last resort in Raynaud’s phenomenon due to scleroderma or haematological disorders such as polycythaemia, cold agglutination, cryoglobulinaemia and sickle-cell disease, where ulceration of the toes has occurred and medical measures have failed.

Raynaud’s syndrome. Lumbar sympathectomy may be a last resort in Raynaud’s phenomenon due to scleroderma or haematological disorders such as polycythaemia, cold agglutination, cryoglobulinaemia and sickle-cell disease, where ulceration of the toes has occurred and medical measures have failed.

Causalgia. Also called reflex sympathetic dystrophy, this burning pain associated with hypersensitivity and vasomotor disturbance is usually a consequence of trauma to a somatic nerve.

Causalgia. Also called reflex sympathetic dystrophy, this burning pain associated with hypersensitivity and vasomotor disturbance is usually a consequence of trauma to a somatic nerve.

Cold injury. Freezing of the foot at temperatures below -1 °C (frostbite) is associated with arterial spasm and capillary sludging. The resultant tissue loss may be diminished by early sympathetic blockade or sympathectomy. Sympathectomy is not beneficial for feet exposed to the cold at temperatures above freezing (trench foot).

Cold injury. Freezing of the foot at temperatures below -1 °C (frostbite) is associated with arterial spasm and capillary sludging. The resultant tissue loss may be diminished by early sympathetic blockade or sympathectomy. Sympathectomy is not beneficial for feet exposed to the cold at temperatures above freezing (trench foot).

Other indications for lumbar sympathectomy are acrocyanosis and erythromyalgia.

Other indications for lumbar sympathectomy are acrocyanosis and erythromyalgia.

SURGICAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMY

Access

1. Place the patient supine with a sandbag beneath the side of the operation to give a 20° tilt.

2. Make an 8–10-cm transverse incision at the level of the umbilicus, starting just medial to the linea semilunaris.

3. Incise the lateral border of the rectus sheath. Split the external oblique muscle and incise the internal oblique with cutting diathermy. Carefully separate the transversalis fascia and muscle without entering the peritoneum. Remember that the peritoneum is tougher laterally.

Action

1. Sweep the peritoneum away from the muscle using finger and swab dissection, continuing this mobilization posteriorly and medially until you expose the aorta on the left or the inferior vena cava on the right.

2. Repair any holes created in the peritoneum before proceeding further. Place a Deaver retractor over the peritoneum laterally and have it pulled firmly to open the retroperitoneal space in front of quadratus lumborum and psoas muscles, while avoiding entering the wrong plane behind these muscles.

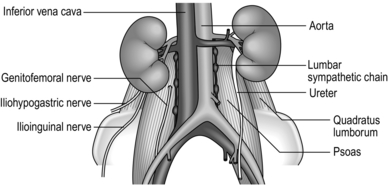

3. Lift the ureter forwards with the peritoneum out of harm’s way. Other structures to avoid which may be confused with the sympathetic chain are the genitofemoral nerve, which runs on the anterior aspect of psoas, the psoas minor tendon and para-aortic lymphatics – identifiable because they are more friable than the sympathetic chain (Fig. 25.5).

4. The sympathetic chain on the left is the easiest to approach as it lies on loose areolar tissue alongside the aorta and can be palpated as a ganglionated cord against the vertebral bodies, where it runs just anterior to the origin of psoas. It passes anterior to the lumbar vessels and posterior to the iliac vessels.

5. On the right side it lies behind the inferior vena cava, which is retracted gently with the tip of the Deaver retractor. Avoid tensing and tearing the lumbar veins, which occasionally pass in front of the sympathetic trunk on this side and can be a source of troublesome bleeding if not recognized and controlled with haemostatic clips.

6. Lift the chain forwards with a nerve hook, diathermize and divide the rami communicantes, then excise the segment containing the second and third ganglia, after applying haemostatic clips, from the lower border of L2 to the lower border of L4.

Aftercare

1. Postoperative ileus is brief unless a retroperitoneal haematoma forms, when it may be prolonged. The haematoma may need draining, but usually peristalsis is restored after 48 hours of a conservative regime.

2. Some patients experience post-sympathectomy neuralgia, a burning pain extending into the thigh. The explanation is unknown, but it resolves after a few weeks.

3. Men in whom both first lumbar ganglia are inadvertently removed will have dry orgasms as a result of damage to the ejaculatory mechanism.

4. Some patients suffer from symptoms of orthostatic hypotension following lumbar sympathectomy.

CHEMICAL LUMBAR SYMPATHECTOMy

Action

1. Position the patient sitting with the legs dependent.

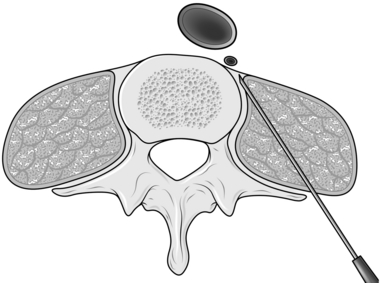

2. Insert a 21 G spinal needle at the level of the upper border of L3, a hand’s breadth away from the midline. Under X-ray or CT image guidance, direct it towards the lumbar vertebral body and reposition as necessary until it just slides off the anterior surface of the vertebra (Fig. 25.6). Aspirate it to ensure that it is not in a blood vessel.

3. Inject radiographic contrast fluid and check the needle position with an image intensifier.

4. If the position is correct, inject 7.5 ml of 7.5% phenol in 50% glycine and nurse the patient sitting for 6 hours to allow the heavy phenol solution to track downwards to bathe the sympathetic trunk, rather than laterally to damage the somatic nerves.