CHAPTER 38 Surgical Treatment for Athletic Pubalgia (“Sports Hernia”)

Basic science

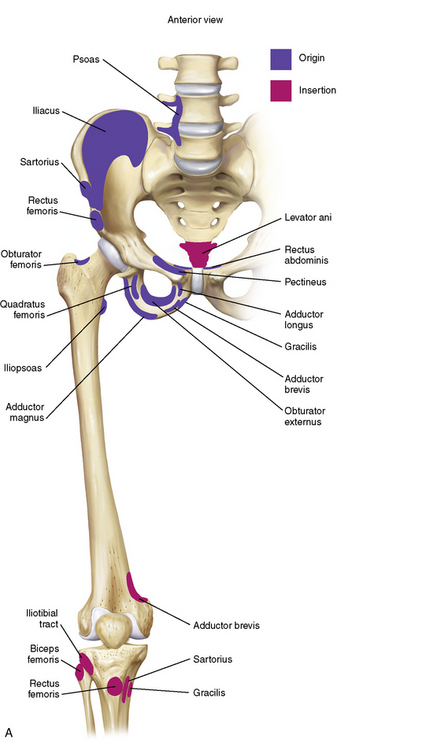

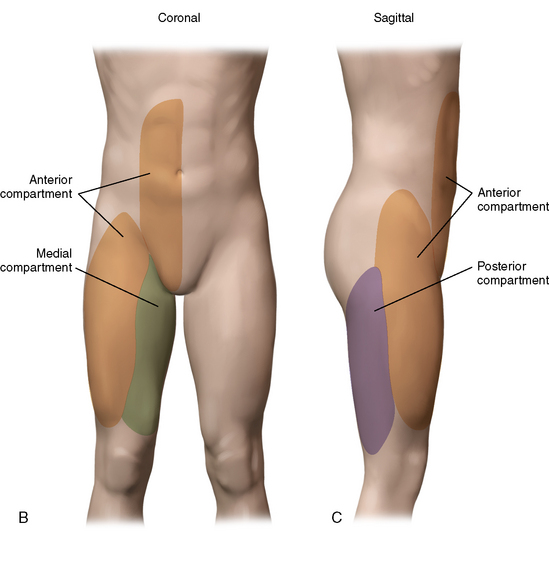

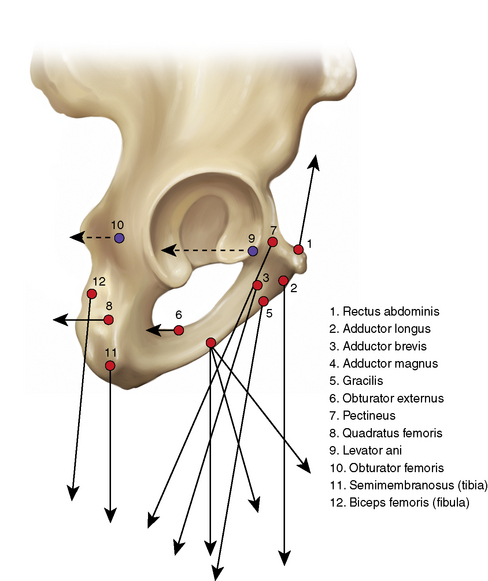

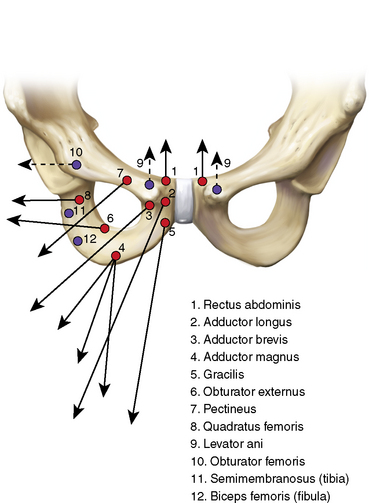

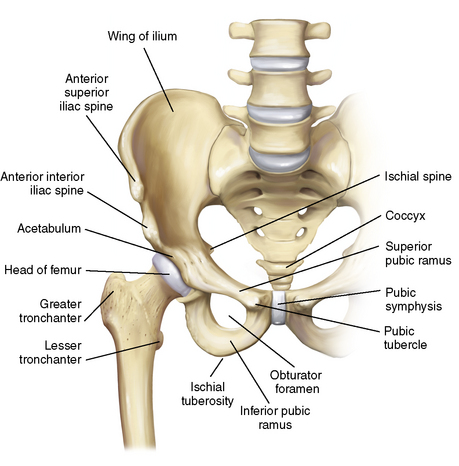

The pubic musculature outside of the hip joint consists of a vast set of muscles and soft tissues. The anterior pelvis includes multiple structures (excluding the hip, sacrum, and spine) such as the lower abdominal soft tissues; both sides of the pubic symphysis; and multiple thigh and pelvic adductors, abductors, flexors, extendors, and rotators. We think in terms of three compartments of muscles or other attachments that provide ligamentous- type support (Figure 38-1). The anterior compartment consists mainly of the abdominal muscles, including the sartorius, the anterior attachment of the psoas, portions of the quadriceps, and some complex interdigitations with fibers from the thighs and the medial and posterior pelvis. The posterior compartment consists primarily of the hamstrings, a portion of the adductor magnus, several key nerves, and an artery. The medial compartment consists of the most important thigh components, which include the three adductors that attach to the symphysis, the gracilis, the obturator externus, and several other structures.

Indications

Surgical technique

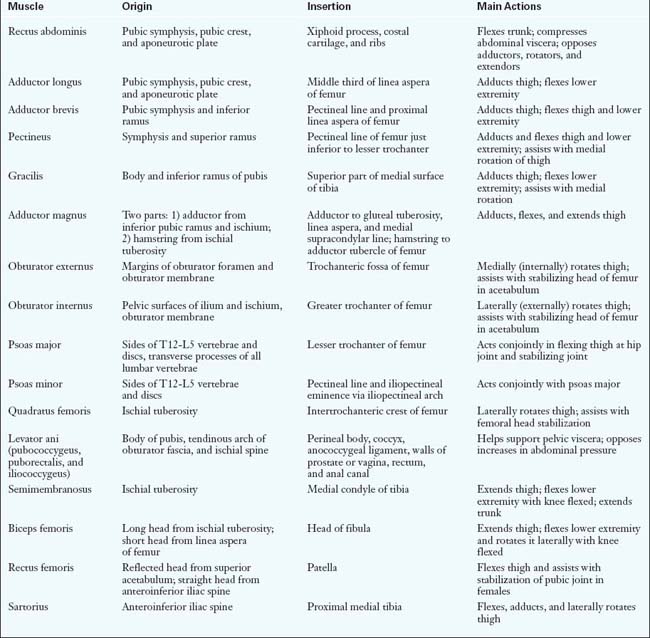

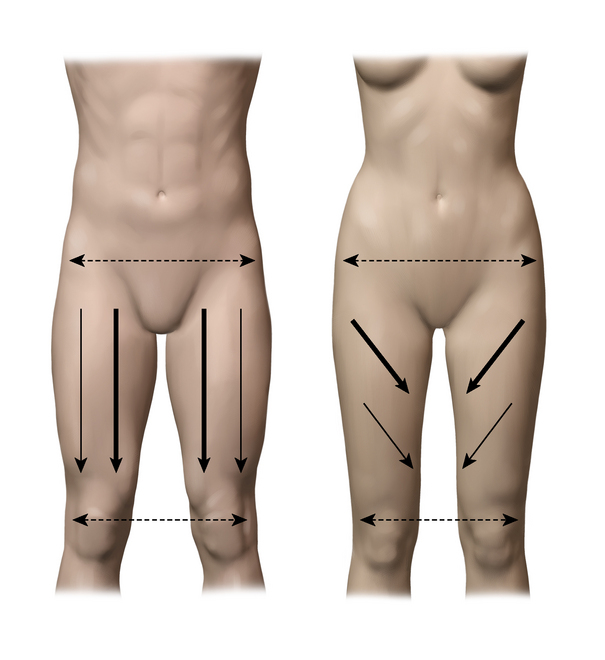

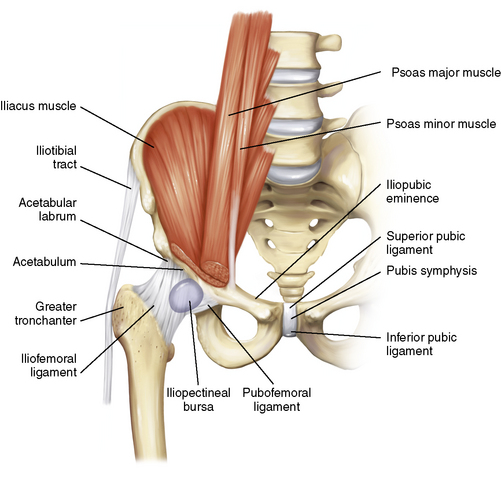

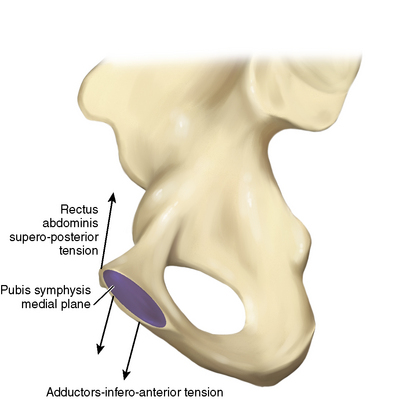

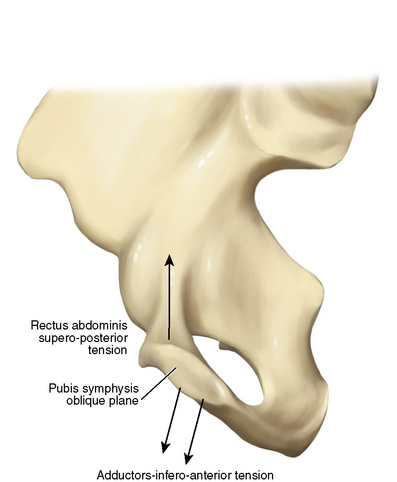

The specific identification of the primary and secondary injuries as well as of the possibility of an associated hip injury provides a guideline for the correction of the problem. First, consider the principal soft-tissue structures that attach to and help stabilize the pelvis. Table 38-1 lists many of these. In general, for males, the more medial structures play greater roles. For women, the lateral structures come more into play. This may be the result of differences in anatomic structure (Figure 38-2). The forces applied to the pubis by these structures are important to consider, and they vary considerably. Note the subtle differences that are schematically represented in the anterior and medial views in Figures 38-3 and 38-4. For each force, there are structures that apply parallel counterforces. In the fresh cadaver laboratory, one can cut certain structures and cause dramatic increases in pressure within other structures or compartments. Such changes in forces likely account for much of what we see clinically in terms of primary and compensatory injuries. The compensatory problems likely result from the “over pulling” of the attachments related to the loss of counterforces and increased pressures within muscles or compartments. Clinically and on a magnetic resonance image, one often finds acute or chronic reactions in the various tissues. These reactions probably represent avulsion, scarring, or tightness within the various compartments involved. Figures 38-5 through 38-8 provide more anatomic direction.

Figure 38–3 Anterior view of the pubic ramus with a schematic depiction of the many forces that act on the pubic joint.

From: Meyers WC, Greenleaf R, Saad A: Anatomic basis for evaluation of abdominal and groin pain in athletes. Oper Tech Sports Med. Elsevier, 13:1, pp 55-61, 2005.

Figure 38–5 Anterior view of the bony anatomy and the proximal femur.

From: Meyers WC, Greenleaf R, Saad A: Anatomic basis for evaluation of abdominal and groin pain in athletes. Oper Tech Sports Med. Elsevier, 13:1, pp 55-61, 2005.

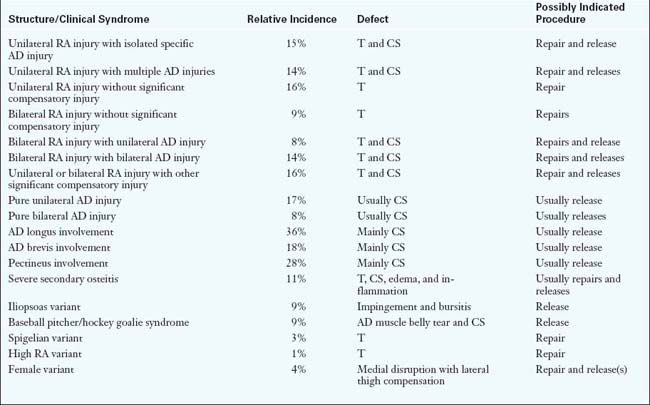

Next, consider the wide variety of musculoskeletal problems that can occur as a result of the disruption of these forces. Table 38-2 lists a number of them that were determined by a recent review of our data. There are still a variety of other problems that are not listed here. The table also summarizes the general approach for the correction of these problems. Initial treatment is usually nonsurgical, and some of these problems can be adequately treated this way. However, when the nonoperative approach does not work, surgery is indicated.

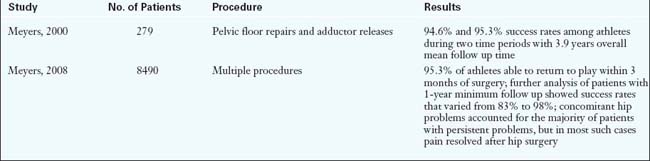

Results

In general, 95% to 96% of athletes can expect to return to sports participation (Table 38-3). The most important endpoints are at 1 and 2 years after surgery. Success rates vary according to multiple factors, such as the site and severity of the injury, concomitant hip injury, and whether the patient is an athlete or a nonathlete. Recurrence rates are about 0.4%, but new involvement of the contralateral side can be as high as 4%. Return to play by 3 months should occur in approximately 90% of patients. Nonathletes and patients without a clear primary injury going into surgery will have a success rate of between 50% and 90%, depending on the specific problem. Workers compensation injuries are less predictable than other injuries with regard to the reporting of successful operations.

Annotated references and suggested readings

Albers S.L., Spritzer C.E., Garrett W.E., Meyers W.C. MRI findings in athletes with pubalgia. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;30:270-277.

Gilmore O.J.A. Gilmore’s groin: ten years of experience of groin disruption—a previously unsolved problem in sportsmen. Sport Med Soft Tissue Trauma.. 1991;3:12-14.

McKechnie McKechnie A., Celebrini R. Hard core strength. Vancouver, BC. Available at http://www.p2soccer.com/Content/Main%20pages/Resource%20Centre.asp

Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, et al. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes. Am J Sports Med. 200;28:2–8.

Meyers W.C., Greenleaf R., Saad A. Anatomic basis for evaluation of abdominal and groin pain in athletes. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2005;13(1):55-61.

Meyers W.C., McKechnie A., Philippon M.J., et al. Experience with “sports hernia” spanning two decades. Presented at the 2008 meeting of the American Surgical Association. Ann Surg. Oct 2008;248(4):656-665.

Meyers W.C., Szalai L., Potter N., et al Extraarticular sources of hip pain. Byrd J.W.T., editor. Operative hip arthroscopy, 2nd ed, Vol 5. New York: Springer, 2005;86-97.

Meyers W.C., Yoo E.Y., Devon O.N., et al. Understanding “sports hernia” (athletic pubalgia): the anatomic and pathophysiologic basis for abdominal and groin pain in athletes. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2007;15:165-177.

Nesovic Nesovic, Treatise on maladies of the pubic symphysis (privately published monograph).

Omar I.M., Zoga A.C., Meyers W.C., et al Athletic pubalgia and the “sports hernia”: optimal MR imaging technique and pictorial review of MR findings. Scientific exhibit. Proceedings of the Radiologic Society of North America, Cum Laude Award winner 2006. Radiographics, 28. 2008:1415-1438.

Swan K.G., Wolcott M. The athletic hernia; a systematic review. Clin Orthop Rel Res.. 2006;455:78-87.

Taylor D.C., Meyers W.C., Moylan J.A., et al. Abdominal musculature abnormalities as a cause of groin pain in athletes. Am J Sports Med.. 1991;19:239-242.

Zoga A.C., Kavanaugh E.C., Meyers W.C., et al MRI of the rectus abdominis/adductor aponeurosis: findings in the “sports hernia.”. Scientific paper presentation, Proceedings of the American Roentgen Ray Society; 2007.

Zoga A.C., Kavanaugh E.C., Meyers W.C., et al. MRI findings in athletic pubalgia and the “sports hernia.”. Radiol. 2008;247(3):797-807.