Chapter 159 Surgical Techniques in the Management of Thoracic Disc Herniations

The initial use of laminectomy to treat herniated thoracic discs was met with uniformly unacceptable results.1,2 As a result, numerous methods have been developed to treat thoracic disc herniations. Unfortunately, no standard algorithm exists to aid the surgeon in selecting the best procedure for a given patient. Each technique offers a combination of advantages and compromises that needs to be evaluated for each patient. Despite the relatively low prevalence of symptomatic thoracic herniated discs, any surgeon managing a moderate proportion of spinal disease in his or her practice will invariably be confronted with this condition. Therefore, a basic understanding of the available surgical options and the indications and limitations of each procedure is vital.

Important Concepts

• Thoracic disc herniations, although uncommon, are encountered by spine surgeons.

• Laminectomy is an unacceptable treatment for thoracic disc herniations.

• Posterior techniques include the transpedicular, Stillerman’s transfacet pedicle sparing, transcostovertebral, costotransversectomy, and lateral extracavitary.

• Posterior approaches are generally favored in cases of more lateral, noncalcified, extradural disc herniations.

• Anterior approaches include the transthoracic, retropleural, and transsternal.

• Anterior techniques offer better ventral exposure for discs that are centrally located, calcified, and/or intradural.

• Complication rates for the common posterior and anterior procedures are similar.

Thoracic disc herniations account for a minority of the disc herniations evaluated by a spine surgeon. This reflects the relative immobility of the thoracic spine as compared with the cervical and lumbar regions and thus the low incidence of degenerative changes. Contemporary series suggest that thoracic herniated discs represent less than 1% of all symptomatic discs and, accordingly, represent less than 1% of all disc operations.1 This establishes an incidence of 1 symptomatic patient per 1 million individuals per year.2–4

The majority of thoracic herniated discs are asymptomatic. As many as 37% of patients harbor an asymptomatic herniated thoracic disc as defined on randomly sampled magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.5 More conservative estimates propose this number lies in the range of 10% to 15%.1,6,7

The majority of symptomatic discs are found in the lower third of the thoracic region, with most being found between the T8 and T11 levels.1,7 Discs in the upper third of the thoracic spine are rare. Herniated discs in the thoracic spine commonly occur centrally within the canal (77% to 94%) and are often calcified (22% to 65%).1,8 A small but very important 6% to 7% of discs prove to be intradural.9

Symptomatic thoracic herniated discs manifest with a wide array of findings. Stillerman and colleagues8 presented an exhaustive review of their personal findings in 71 patients with thoracic disc disease as well as a meta-analysis of 13 series encompassing 247 patients (Table 159-1). Both of these surveys demonstrated that sensory changes were seen in more than 60% of cases. Pain was a finding in greater than half of the patients but was actually more likely to be axial than the typically presumed radicular pattern. Motor weakness and spasticity or hyperreflexia were present in 55% to 58% of patients. As with many cervicothoracic lesions, bowel and bladder dysfunction was one of the least-common symptoms, appearing in only 24% to 35% of patients.8

Table 159-1 Comparison of the Present Study and Earlier Thoracic Disc Series

| Factor | 13 Contemporary Series (1986-1997) | Present Study |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics and Disc Characteristics | ||

| No. of patients/no. of discs | 247/263 | 71/82 |

| Sex (F/M) | 112/95 (1.18/1) | 37/34 (1.09/1) |

| Age, yr | 18-79 | 19-75 |

| Trauma | 37% (59/161) | 37% (26/71) |

| Levels (total) | T1-L1 (244) | T4-L1 (82) |

| Level/frequency (no.) | T8-9: 17% (41) | T9-10: 26% (21) |

| T11-12: 16% (39) | T8-9: 23% (19) | |

| T10-11: 11% (26) | T10-11: 17% (14) | |

| Calcified | 22% (33/151) | 65 % (53/82) |

| Intradural | 6% (5/90) | 7% (6/82) |

| Canal location | ||

| Central/centrolateral | 77% (113/146) | 94% 77/82) |

| Lateral | 23% (33/146) | 6% (5/82) |

| Multiple discs | 8% (20/242) | 14% (10/71) |

| Presenting Signs and Symptoms | ||

| Localized/axial pain | 56% (111-199) | 61% (43/71) |

| Radicular pain | 51% (94/185) | 16% (11/71) |

| Sensory deficit | 64% (145/226) | 61% (43/71) |

| Bowel/bladder deficit | 35% (72/208) | 24% (17/71) |

| Motor impairment | 55% (114/208) | 61% (43/71) |

| Results∗ | ||

| Pain/total | 76% (106/140) | 87% (47/54) |

| Localized/axial | 80% (39/49) | 86% (37/43) |

| Radicular | 74% (29/39) | 91% (10/11) |

| Sensory deficit | NR | 84% (36/43) |

| Bowel/bladder deficit | 80% (47/59) | 77% (13/17) |

| Motor impairment | 69% (65/94) | 58% (25/43) |

NR, not reported.

∗ Number resolved or improved/total number of patients in groups reporting this result.

From Stillerman CB, Chen TC, Couldwell WT, et al: Experience in the surgical management of 82 symptomatic herniated thoracic discs and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 88:623-633, 1998.

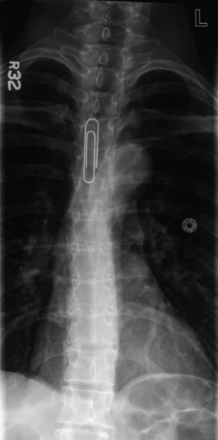

The radiographic identification of these lesions is obviously most commonly performed with MRI. MRI allows visualization of the disc herniation and the surrounding neural elements (Fig. 159-1). However, computed tomography/myelography remains a viable imaging technique with excellent resolution of the affected region, despite the inconvenience and invasiveness of the procedure. Plain computed tomography scanning also serves a supportive role because it often assists MRI in evaluating whether a given disc is calcified and offers a better analysis of the bony anatomy (Fig. 159-2).

FIGURE 159-1 Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a thoracic herniated disc and associated syrinx.

FIGURE 159-2 Axial computed tomography scan of same patient demonstrates calcification of the herniated disc.

Selecting patients for surgery is much like selection for degenerative processes afflicting the remainder of the spine. That is, the indications for surgery are by no means objectified and established but rather are physician defined. As with most cervical lesions, myelopathy with or without bowel or bladder involvement is a nearly absolute operative indication. Surgical treatment of thoracic herniated discs for radiculopathy, back pain, or sensory changes is much more difficult to uniformly define. The natural history of thoracic disc herniations is not completely understood. Brown and colleagues10 followed 40 patients with symptomatic thoracic disc herniations and determined that 77% returned to work symptom free without surgical intervention. Therefore, an argument can be made to manage patients who do not have significant neurologic insult (weakness, spasticity) in a fashion similar to those with degenerative cervical and lumbar conditions. These nonoperative measures can include a combination of rest, physical therapy, oral antiinflammatory medication (steroidal and/or nonsteroidal), and/or steroid injections.

One of the reasons for the development of this variety of procedures is the surgical constraint of the thoracic spine anatomy. In this region, the spinal cord lies within the relatively narrow thoracic spinal canal and the thecal sac cannot be manipulated as freely as within the lumbar region. Therefore, the operative approach needs to minimize manipulation of the dura and spinal cord. Although this feature is similar to the cervical region, the anterior approaches to the thoracic region (excluding the very superior thoracic spine) are more involved than standard anterior cervical procedures. Thus the ideal procedure would afford the surgeon a ventral view of the region while maintaining the more straightforward technical aspect of a posterior approach. As a result of these requirements, more-aggressive posterior procedures have been developed in attempts to gain greater “anterior” perspectives and circumvent the need for more-involved anterior thoracic exposures.

Considerations for an operative approach for herniated thoracic discs include the following:

• Mediolateral localization of the herniation (location with respect to canal and cord and the foramen and root and the resultant symptoms)

• Complicating factors of the disc itself (intradural, calcification)

Although not inclusive, the following guidelines can be made in terms of operative approaches.

Intraoperative Localization

First, a surgeon needs to identify the level of a herniated disc using the same method by which the preoperative level is identified. That is, if the preoperative investigations identify the affected thoracic level counting down from C1, then the surgeon should not necessarily use the sacrum as a reference point intraoperatively, because a lumbarized sacral segment could obviously cause an error in localization. Rather, the surgeon can employ an intraoperative anteroposterior (AP) radiograph and count down from the first thoracic ribs, or the sacrum can be used to count upward, if this has been confirmed as an accurate means of reference. A preoperative localization can be easily performed by taping a radiopaque marker to the patient and obtaining a standard AP radiograph (Fig. 159-3).

Description of Individual Procedures

Posterior Procedures

Transpedicular

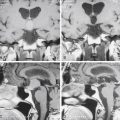

The transpedicular approach is perhaps the most commonly considered procedure for a thoracic disc herniation. Its origins date to the initial description of Patterson and Arbit11 in 1978, which represent a modification of Carson’s12 1971 technique. The transpedicular approach allows the surgeon relatively straightforward access into the most lateral region of the spinal canal ventral to the spinal cord (Fig. 159-4). The patient is placed in a prone position on gel rolls or a Wilson frame, and a vertical midline incision is centered over the level of interest. Sharp dissection is carried deeply to the thoracodorsal fascia. A unilateral exposure can be performed to minimize trauma to the contralateral paravertebral musculature. Once through the thoracodorsal fascia, a subperiosteal dissection is performed with Cobb elevators until the lateral facets are exposed on the affected side.

FIGURE 159-4 Schematic demonstrates the region of bone removal in the transpedicular approach.

(From Fessler RG, Sturgill M: Review: Complications of surgery for thoracic disc disease. Surg Neurol 49:609-618, 1998.)

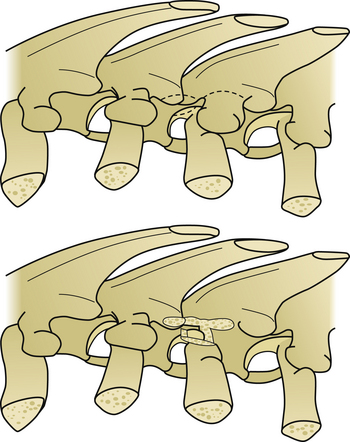

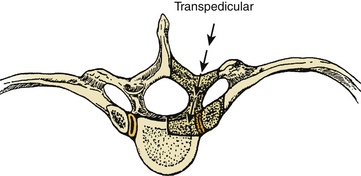

Viewing the facet joints, the surgeon needs to then develop an idea as to the location of the pedicle and the associated nerve root. The thoracic pedicle to be drilled is centered 1 to 2 mm beneath the edge of the inferior facet of the superior vertebra (Fig. 159-5). For example, a for a T7–8 disc herniation the surgeon will aim to drill the T8 pedicle, which is centered just below the inferior edge of the T7 inferior facet.

FIGURE 159-5 Transpedicular approach after drilling of facet and superior pedicle.

(From Kumar R, Dunsker SB: Surgical management of thoracic disc herniations. In Schmidek HH, Sweet WH (eds): Operative Neurosurgical Techniques, 4th ed. New York: WB Saunders, 2000, pp 2122-2131.)

Closure resembles that of posterior lumbar and cervical procedures.

Transfacet Pedicle Sparing

This technique shares many similarities with the transpedicular approach but avoids the resection of the pedicle. Devised by Stillerman and colleagues,13 the technique employs a setup similar to that used in the transpedicular technique. The patient is positioned prone. Stillerman and colleagues recommend the use of AP fluoroscopy to verify the proper level during the exposure. A linear midline incision is used, and the standard dissection and subperiosteal exposure is performed so as to expose the ipsilateral facet joint.

At this point, the proper disc level and overlying facet joint are verified with fluoroscopy. As with the transpedicular procedure, a pneumatic drill is used to penetrate the medial aspect of the facet joint. Unlike the previous procedure, the inferiorly lying pedicle is not entered with the drill. Once the surgeon reaches neural foramen, blunt dissection may be performed to visualize the disc space lying at the inferior aspect of the foramen (Fig. 159-6). The exiting nerve root is usually found in the extreme superior aspect of the foramen and therefore is often not encountered (except in the higher thoracic spine). Once the annulus is identified, the disc removal proceeds in a fashion similar to that of any of the other posterior procedures.

Transcostovertebral Approach

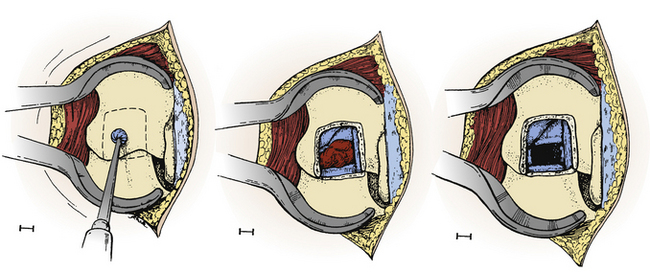

Another, more recent posterolateral approach has been described by Dinh and colleagues,3 in which only the posterior cortex of the rib head is removed, thus allowing an increased lateral exposure while not incurring the potential disadvantages of complete rib resection. In this procedure, the patient is once again positioned on the operating table in a prone position. A midline incision is used, typically spanning the adjacent superior and inferior disc spaces. A standard subperiosteal dissection is performed, but the exposure is extended laterally to visualize the transverse process. At this point, the transverse process is removed to reveal the underlying rib head. Using a diamond-tipped drill, the lateral one half of the facet joint and the upper one third to one half of the pedicle are removed (Fig. 159-7). This allows visualization of the spinal cord and exiting nerve root. Further ventral drilling is performed through the posterior cortex of the rib head until the annulus is identified medially. The authors emphasize that the key to this procedure is “staying within the costovertebral joint and drilling outward circumferentially to include immediate adjacent structures such as the posterior cortex of the rib head and the lateral endplates above and below the annulus.”3 Once the annulus is exposed, the disc can be removed in the standard fashion by central decompression of the disc and removal of the herniation via the newly formed central cavity.

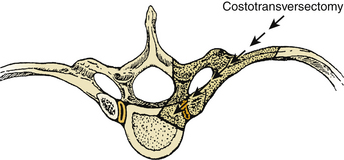

Costotransversectomy

The next progression in terms of a greater lateral exposure through a posterior incision is the costotransversectomy. Recognition has been awarded to both Hulme and Menard for the development of this procedure.9,14

This technique offers a more lateral working corridor than the transpedicular route and hence affords a better view of the anterior spinal canal (Fig. 159-8). To do so, the costotransversectomy requires a more extensive muscular and bony dissection, often leading to more postoperative discomfort.

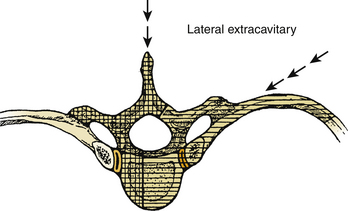

Lateral Extracavitary

The term lateral extracavitary approach was first coined by Larson and colleagues15 in 1976 for a technique for treating traumatic thoracic spine injuries. However, this was a modification of Capener’s16 1954 technique for treating tuberculous spondylitis.17

This procedure typically uses one of two incisions: a hockey-stick incision with the vertical segment centered over the affected level or a curvilinear incision with the convexity facing medially. The major difference between the lateral extracavitary approach and the costotransversectomy is that a larger lateral resection of the inferior rib is performed (Fig. 159-9). This allows a lower viewing angle toward the canal. If a hemilaminectomy is performed, the nerve root overlying the disc space can be ligated, incised, and then used to rotate the thecal sac dorsally. The disc material is removed in the same manner as the preceding techniques. If necessary, portions of the vertebral body can be drilled to facilitate disc manipulation. If this is performed, then portions of resected rib can be placed as strut grafts between the vertebral bodies.

Closure is performed in a manner similar to that for costotransversectomy.

Mini-Open Procedures

Increasingly, surgeons are adopting mini-open procedures for thoracic pathology.18,19 Originally popularized for use in the lumbar spine, the mini-open or tubular techniques use a series of dilating tubes to spread the paravertebral musculature. With this technique, the patient could presumably experience less postoperative pain, less postoperative narcotic use, and a shorter hospital admission.

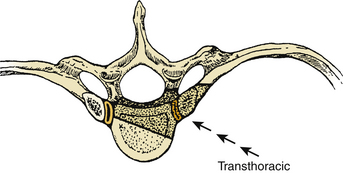

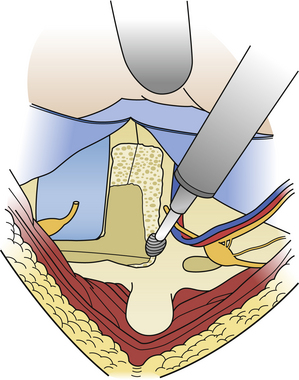

Transthoracic Procedure (Adapted from Vollmer and Simmons20)

The rib head is removed with rongeurs, drills, or both. Resection of the rib allows access to the posterolateral aspect of the disc and the intervertebral foramen. At this point, the surgeon needs to identify the disc margins, the intervertebral foramen, and the pedicles above each foramen. The pedicle inferior to the desired disc space can be drilled away with a diamond-tipped drill to allow greater visualization of the exiting nerve root and thecal sac. Because of the typically narrow thoracic disc spaces, the posterolateral portions of the vertebral bodies might need to be drilled away to adequately access the disc space itself. Larger and more centrally located disc herniations often require more aggressive drilling, in some cases even extending beyond the midpoint of the ventral spinal canal (Fig. 159-10). Exposure of this portion of the disc allows an incision to be made in the lateral annulus. Using curets, the dorsal herniation can then be manipulated into the cavity created by the initial disc removal. This portion of the procedure can be performed under loupe magnification, although the operating microscope allows superior magnification and illumination.

Retropleural Thoracotomy

Although the transthoracic approach offers a clear visualization of the thoracic spinal canal, it carries the inherent complications of entering the thoracic cavity. McCormick21 introduced the retropleural approach as an alternative means of ventrolateral access to the spine.

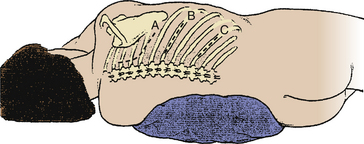

Positioning is similar to that of the transthoracic procedure. The patient is placed in a lateral position on a beanbag, preferably with the lesion lying directly over a break in the operating table. The incision is slightly smaller than in the transthoracic procedure. In the midthoracic spine, the incision is placed over the rib of interest, extending from several centimeters off midline to the posterior axillary line. Higher thoracic lesions necessitate a hockey-stick incision, and lower thoracic lesions are best approached by making an incision over the 10th rib (Fig. 159-11).

FIGURE 159-11 Incisions for the retropleural thoracotomy in the upper (A), mid- (B), and lower (C) thoracic regions.

(From McCormick PC: Retropleural approach to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Neurosurgery 37:908-914, 1995.)

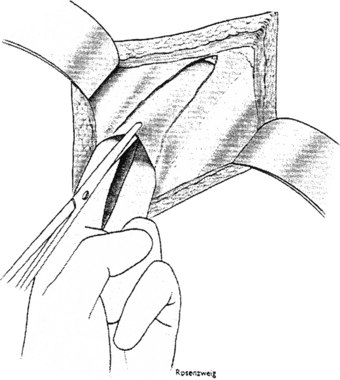

Once this portion of the rib is removed, the endothoracic fascia is identified. This layer of tissue encompasses the entire thoracic cavity and the parietal pleura. By incising this fascia along the longitudinal axis of the recently removed rib, the parietal pleura is exposed (Fig. 159-12). Using blunt dissection, the parietal pleura can be gently dissected free from the inner aspect of the fascia toward the spine. When necessary, the remaining portion of rib can be disarticulated and removed to allow additional exposure. A malleable retractor is placed over the parietal pleura to prevent entrance into the thoracic cavity and to facilitate the exposure of the disc space.

FIGURE 159-12 Incision of the endothoracic fascia, allowing exposure of the pleura.

(From McCormick PC: Retropleural approach to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Neurosurgery 37:908-914, 1995.)

The periosteum and investing tissues are then dissected off the vertebral body. The neural foramen is identified, along with the pedicle and the superiorly lying disc space. At this point, disc space manipulation remains the same as in the transthoracic procedure. The end plates and pedicle are removed via a pneumatic drill (Fig. 159-13). Closure is also the same, being sure to check for tears in the parietal pleura and closing these with sutures as needed. A chest tube is generally not needed unless a large tear in the pleura is encountered.

Transsternal Approach to Thoracic Spine (T1-5)

An orogastric tube can be placed in the esophagus to improve intraoperative identification of this structure. Several incisions can be used to perform this procedure including a midline T-shaped incision or a vertical incision over the sternal region, which curves to one side or another as it extends superiorly into the lower cervical region. The upper portion of the dissection is similar to that of an anterior cervical procedure. Fascial attachments to the sternum are removed, and the surgeon can insert a finger to bluntly dissect along the underside of the sternum. The sternum is then opened with a sagittal saw, whereupon a sternal retractor is placed. At this point, the major vessels are identified, along with the pericardium and thymus. The inferior thyroid artery and vein can be ligated for additional exposure.22 The thymus is reflected to the patient’s right side, affording a window of operative exposure just medial to the left common carotid artery.9 Disc manipulation is then carried out in the fashion similar to that of anterior cervical surgery. In addition to the vascular and neurologic structures, care must be taken to avoid injury to the thoracic duct, which ascends along the esophagus and eventually runs behind the left subclavian artery to enter the internal jugular vein.

Complications

Since the abandonment of laminectomy for thoracic disc herniations, morbidity and mortality rates have dropped significantly.2 Obviously, the type of complication differs with the specific procedure, because pneumonia and hemo- and chylothorax are more commonly seen after a transthoracic procedure than after a transpedicular procedure. Again, complications of some procedures may be accepted outcomes in others. For example, a pleural tear is an undesirable outcome during a costotransversectomy, but a pleural incision is intentionally performed in a transthoracic procedure.

Despite these difficulties in comparing the complication rates, the morbidity and mortality associated with currently accepted procedures appear similar.2,23 Fessler and Sturgill2 demonstrated that since 1986, reported complication rates for all thoracic disc surgeries ranged from 8% to 16%. When analyzed with respect to procedure, morbidity rates were 9% for transpedicular, 12% for costotransversectomy, 12% for lateral extracavitary, and 11% for transthoracic procedures. No mortality was noted.

Infection rates ranged from 1% to 3%, which compare favorably with those of other spinal surgeries.2 Neurologic worsening was seen in approximately 1% of cases.2,9

In regard to the newer procedures mentioned in this chapter, reports of the transfacet pedicle-sparing procedure of Stillerman and colleagues13 and the transcostovertebral approach of Dinh and colleagues3 mentioned no complications in the their analyses of 6 and 22 patients, respectively.

Awaad E.E., Martin D.S., Smith K.R.Jr., et al. Asymptomatic versus symptomatic herniated thoracic discs: their frequency and characteristics as detected by computed tomography after myelography. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:180-186.

Brown C.W., Deffer P.A., Akmakjian J., et al. The natural history of thoracic disc herniation. Spine. 1992;17:S97-S102.

Capener N. The evolution of lateral rhachotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36:173-179.

Carson J., Gumpert J., Jefferson A. Diagnosis and treatment of thoracic intervertebral disc protrusions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1971;34:68-77.

Chi J.H., Dhall S.S., Kanter A.S., et al. The Mini-open transpedicular thoracic discectomy: surgical technique and assessment. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:1-5.

Debnath U.K., McConnell J.R., Sengupta D.K., et al. Results of hemivertebrectomy and fusion for symptomatic thoracic disc herniation. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:292-299.

Delfinia R., Lorenzo N.D., Ciappetta P., et al. Surgical treatment of thoracic disc herniation: a reappraisal of Larson’s lateral extracavitary approach. Surg Neurol. 1996;45:517-523.

Dinh D.H., Tompkins J., Clark S.B. Transcostovertebral approach for thoracic disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:38-44.

Fessler R.G., Sturgill M. Review: complications of surgery for thoracic disc disease. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:609-618.

Hulme A. The surgical approach to thoracic intervertebral disc protrusions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:133-137.

Knoller S.M., Brethner L. Surgical treatment of the spine at the cervicothoracic junction: an illustrated review of a modified sternotomy approach with the description of tricks and pitfalls. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:365-368.

Kumar R., Dunsker S.B. Surgical management of thoracic disc herniations. In: Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 4th ed. New York: WB Saunders; 2000:2122-2131.

Larson S.J., Holst R.A., Hemmy D.C., et al. Lateral extracavitary approach to traumatic lesions of the thoracic and lumbar spine. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:628-637.

McCormick P.C. Retropleural approach to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:908-914.

Mulier S., Debois V. Thoracic disc herniations: transthoracic, lateral, or posterolateral approach? A review. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:599-608.

Patterson R.H., Arbit E. A surgical approach through the pedicle to protruded thoracic discs. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:768-772.

Sheikh H., Samartzis D., Perez-Cruet M.J. Techniques for the operative management of thoracic disc herniation: minimally invasive thoracic miscrodiscectomy. Orthop Clin N Am. 2007;38:351-361.

Stillerman C.B., Chen T.C., Couldwell W.T., et al. Experience in the surgical management of 82 symptomatic herniated thoracic discs and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:623-633.

Stillerman C.B., Chen T.C., Diaz Day J., et al. The transfacet pedicle-sparing approach for thoracic disc removal: cadaveric morphometric analysis and preliminary clinical experience. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:971-976.

Stillerman C.B., McCormick P.C., Benzel E.C. Thoracic discectomy. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Spine Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:369-387.

Vollmer D.G., Simmons N.E. Transthoracic approaches to thoracic disc herniations. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:1-6.

Wood K.B., Blair J.M., Aepple D.M., et al. The natural history of asymptomatic thoracic disc herniations. Spine. 1997;22:525-529.

Wood K.B., Garvey T.A., Gundry C., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine: evaluation of asymptomatic individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1631-1638.

1. Debnath U.K., McConnell J.R., Sengupta D.K., et al. Results of hemivertebrectomy and fusion for symptomatic thoracic disc herniation. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:292-299.

2. Fessler R.G., Sturgill M. Review: complications of surgery for thoracic disc disease. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:609-618.

3. Dinh D.H., Tompkins J., Clark S.B. Transcostovertebral approach for thoracic disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:38-44.

4. Wood K.B., Blair J.M., Aepple D.M., et al. The natural history of asymptomatic thoracic disc herniations. Spine. 1997;22:525-529.

5. Wood K.B., Garvey T.A., Gundry C., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine: evaluation of asymptomatic individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1631-1638.

6. Awaad E.E., Martin D.S., Smith K.R.Jr., et al. Asymptomatic versus symptomatic herniated thoracic discs: their frequency and characteristics as detected by computed tomography after myelography. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:180-186.

7. Kumar R., Dunsker S.B. Surgical management of thoracic disc herniations. In: Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 4th ed. New York: WB Saunders; 2000:2122-2131.

8. Stillerman C.B., Chen T.C., Couldwell W.T., et al. Experience in the surgical management of 82 symptomatic herniated thoracic discs and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:623-633.

9. Stillerman C.B., McCormick P.C., Benzel E.C. Thoracic discectomy. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Spine Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999:369-387.

10. Brown C.W., Deffer P.A., Akmakjian J., et al. The natural history of thoracic disc herniation. Spine. 1992;17:S97-S102.

11. Patterson R.H., Arbit E. A surgical approach through the pedicle to protruded thoracic discs. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:768-772.

12. Carson J., Gumpert J., Jefferson A. Diagnosis and treatment of thoracic intervertebral disc protrusions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1971;34:68-77.

13. Stillerman C.B., Chen T.C., Diaz Day J., et al. The transfacet pedicle-sparing approach for thoracic disc removal: cadaveric morphometric analysis and preliminary clinical experience. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:971-976.

14. Hulme A. The surgical approach to thoracic intervertebral disc protrusions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:133-137.

15. Larson S.J., Holst R.A., Hemmy D.C., et al. Lateral extracavitary approach to traumatic lesions of the thoracic and lumbar spine. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:628-637.

16. Capener N. The evolution of lateral rhachotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36:173-179.

17. Delfinia R., Lorenzo N.D., Ciappetta P., et al. Surgical treatment of thoracic disc herniation: a reappraisal of Larson’s lateral extracavitary approach. Surg Neurol. 1996;45:517-523.

18. Chi J.H., Dhall S.S., Kanter A.S., et al. The Mini-open transpedicular thoracic discectomy: surgical technique and assessment. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25:1-5.

19. Sheikh H., Samartzis D., Perez-Cruet M.J. Techniques for the operative management of thoracic disc herniation: minimally invasive thoracic miscrodiscectomy. Orthop Clin N Am. 2007;38:351-361.

20. Vollmer D.G., Simmons N.E. Transthoracic approaches to thoracic disc herniations. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:1-6.

21. McCormick P.C. Retropleural approach to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:908-914.

22. Knoller S.M., Brethner L. Surgical treatment of the spine at the cervicothoracic junction: an illustrated review of a modified sternotomy approach with the description of tricks and pitfalls. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:365-368.

23. Mulier S., Debois V. Thoracic disc herniations: transthoracic, lateral, or posterolateral approach? A review. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:599-608.