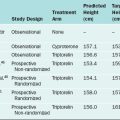

Chapter 51 Surgical Techniques for Management of Anomalies of the Müllerian Ducts and External Genitalia

INTRODUCTION

Malformations of the müllerian ducts and the external genitalia can have significant impact on both reproductive potential and sexual function. When a patient presents with such an abnormality, it is important to put significant thought and time into determining the correct diagnosis and subsequent treatment. This is particularly true for surgical management of external genitalia anomalies, where consequences, in terms of gender assignment and later sexual function, remain largely uncertain.

This chapter begins with a review of the diagnostic and presurgical evaluation of these anomalies. The majority of the chapter deals with basic principles of surgical techniques used to correct these anomalies. The pathophysiology of genital anomalies is reviewed in Chapter 12.

CLASSIFICATION

The classification of müllerian anomalies helps with both diagnosis and the comparison of outcomes after various modes of management. However, there is no single classification that encompasses all anomalies that have been reported in the literature.1–3

On the basis of pathophysiology, müllerian anomalies can be broadly classified into problems according to the developmental mechanism whose failure gave rise to the malformation. Anomalies can usually be classified as being related to (1) agenesis, (2) vertical fusion defects, or (3) lateral fusion defects.4

The most accepted classification of uterine anomalies, published by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), places uterine anomalies into distinct groups based on anatomic configuration (Table 51-1).5 Because vaginal anomalies are not included in this classification, they must be described along with the uterine anomaly. This classification does not give insight into pathophysiology, but it is an effective way to communicate observations for purposes of treatment and prognosis.

MÜLLERIAN AGENESIS

Clinical Presentation

Müllerian agenesis (i.e., Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome) was first described in 1829. Its incidence is reported to be 1 in every 5000 newborn females.6 Because the vagina and associated uterine structures do not develop with this disorder, it is a ASRM Class IA müllerian anomaly. Patients typically present during their adolescent years with complaint of primary amenorrhea. As a cause of primary amenorrhea, müllerian agenesis is second only to gonadal dysgenesis.7

Because these patients have a 46,XX karyotype, normal ovaries will be present in the pelvis. Ovulation can be documented as a shift in basal body temperature. These patients’ hormonal levels are normal, and their cycle length based on hormonal studies varies from 30 to 34 days.8 In addition they may experience the monthly pain (mittelschmertz) that is indicative of ovulation.

Associated Anomalies

Some but not all anomalies described can be extrapolated from the embryology.9–12 Hearing difficulties have been reported in patients with müllerian agenesis.10,11 A higher rate of auditory defects have been noted in general in patients with müllerian anomalies compared to those with normal müllerian structures.12

Müllerian agenesis is associated with renal and skeletal system anomalies. Renal abnormalities are noted in 40% of these patients. These include complete agenesis of a kidney, malposition of a kidney, and changes in renal structure.13 Skeletal abnormalities are noted in 12% of patients and include primarily spine defects followed by limb and rib defects.14 Patients with müllerian agenesis should be actively assessed for these associated anomalies.

Etiology

The etiology of müllerian agenesis remains unknown. It appears to be influenced by multifactorial inheritance, and rare familial cases have been reported. It does not appear to be transmitted in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, because none of the female offspring of women with müllerian agenesis (born via in vitro fertilization [IVF] and surrogacy) have shown evidence of vaginal agenesis.9

CREATION OF A NEOVAGINA

The first goal of treatment of müllerian agenesis is creation of a functional vagina to allow intercourse. Frank first proposed vaginal dilation with use of a dilator as a means of creating a neovagina in 1938.15 However, the surgical techniques of vaginoplasty remained the preferred methods for many years. The success of any technique depends in large part on the emotional maturity of the patient. Pretreatment counseling and continued support during treatment is important.

Vaginal Dilation

The simplicity and ease of vaginal dilation and its significantly lower complication rate than surgical techniques dictates its use as initial form of therapy for most patients with müllerian agenesis. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recently released a committee opinion that recommends nonsurgical management of müllerian agenesis as the first mode of treatment.16

Frank’s technique of dilation involves actively placing pressure with the dilators against the vaginal dimple (Fig. 51-1). The patient is not only in an awkward position, but the hand applying the pressure can also become tired. In 1981, Ingram proposed the concept of passive dilation, where pressure is placed on the dilator by sitting on a bicycle seat.17

Roberts reported a success rate of 92% in women who dilated the vagina via the Ingram technique for 20 minutes three times a day.18 The average time to creation of a functional vagina was 11 months. This series demonstrated that an initial dimple less than 0.5cm was all that was necessary to achieve adequate dilation. Interestingly, failure of this technique was not related to length of vaginal dimple but rather was more closely associated with the patient’s youth. Failure of this technique was more common in patients younger than age 18.

Procedure

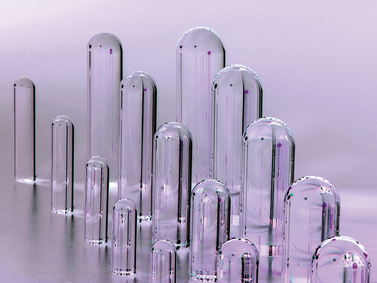

When the patient expresses a desire to proceed with therapy, she is shown the exact location of her vaginal dimple. The axis of dilator placement is also demonstrated (Fig. 51-2). The process is initiated by placement of the smallest dilator against the dimple. Pressure is kept on the distal aspect of the dilator by sitting on a stool while leaning slightly forward. When the dilator fits comfortably she moves to the next size dilator. The patient is instructed to use this technique a minimum of 20 minutes a day, two to three times a day. In motivated patients, a functional vagina can be created in as short as 12 weeks.

Counseling and psychological support is integral to successful treatment.19–21 Patients are requested to return to the office frequently to monitor their progress, provide guidance, and have an opportunity to answer questions. Intercourse may be attempted when the largest dilator fits comfortably.

Multiple types of graduated dilators, made of various materials, are present on the market. None have been found superior to the others. Patients may stop and reinitiate the dilation at any time without any negative long-term sequelae. Although most patients appear interested in initiating this therapy the summer before college when they are mature enough and motivated to create the vagina, the timing of therapy is purely dependent on the patient’s desires. The median age of starting treatment is 17 years.22 For appropriately selected motivated patients, the reported success rates are as high as 90%.23

Vecchietti Procedure

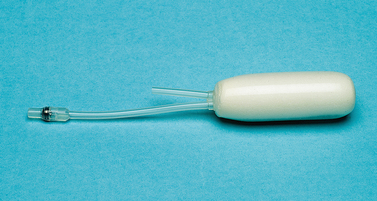

Giuseppe Vecchietti described this method of creating a neovagina in 1965.24 Similar to vaginal dilation, this method avoids the use of a graft. The Vecchietti procedure is a one-step procedure in which a neovagina is created in 7 days by continuous pressure on the vaginal dimple using an acrylic olive connected by retroperitoneal sutures to a spring-tension device on the lower abdomen. Although the original description of the Vecchietti procedure utilized laparotomy, this technique is currently performed laparoscopically.25,26

Procedure

The next step is to use a curved blunt ligature carrier to burrow retroperitoneally from a lateral suprapubic laparoscopic port site to the peritoneal fold between the bladder and the uterine rudiment. One end of the olive suture is placed through the eye of this curved ligature carrier and pulled retroperitoneally back through the abdominal wall port site incision. This procedure is repeated on the opposite side with the other end of the suture. After the laparoscope is removed and the abdominal wall incisions are closed, the ends of the suture are attached to a suprapubic Vecchietti spring-traction device located externally on the abdomen.25

Vecchietti reported a series of more than 500 patients with a success rate of 100% and only nine complications, including one bladder and one rectal fistula.27 Several smaller studies have subsequently been reported by other surgeons with similar outcomes.28,29 A 3-year follow-up study assessed the functional and psychological outcome in five patients.30 All five subjects reported having a functioning vagina allowing satisfactory intercourse and improvement in general well-being.

Vaginoplasty Techniques

The traditional surgical management of vaginal agenesis is to create a vaginal space followed by placement of a lining to prevent stenosis. Multiple tissues and at least one manmade material have been used to line this cavity with varying degrees of success in preventing subsequent stenosis of the neovagina (Table 51-2).

McIndoe Procedure

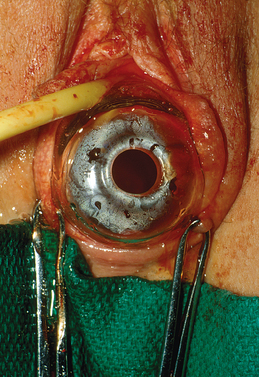

The skin graft is placed through a 1:5 ratio skin mesher. The purpose of meshing the skin is not to stretch it but rather to allow escape of any underlying blood clots or serous fluids. This skin graft is sutured around the mold with 4-0 absorbable suture (Fig. 51-3). The mold is covered completely, because any uncovered sites, whether due to lack of enough tissue or a gaping hole in the line of suture, tend to result in the formation of granulation tissue. Thus great care must be taken to obtain a sufficient amount of graft for this procedure.

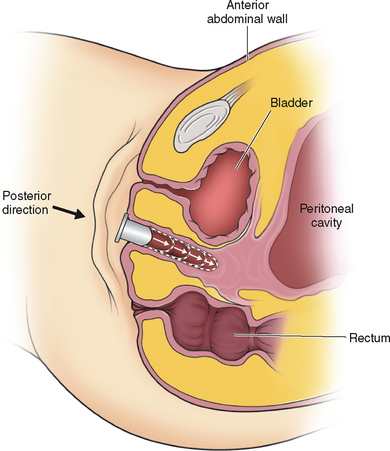

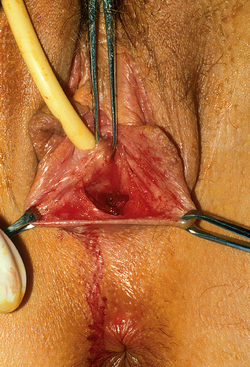

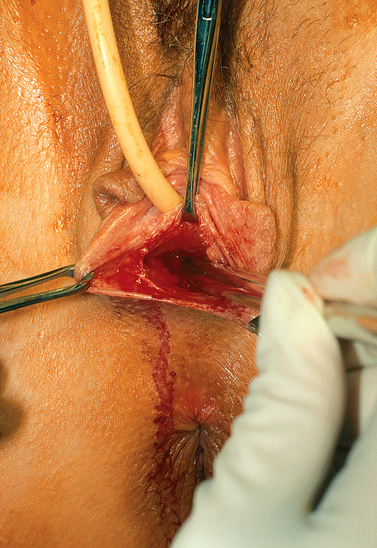

The patient is placed in the dorsolithotomy position. A transverse incision is made in the vaginal vestibule, between the rectum and urethral openings (Fig. 51-4). In a patient who has not had prior surgery or radiation in the area, areolar tissue is now encountered. This tissue is easily dissected with either fingers or a Hagar dilator on either side of a median raphe (Fig. 51-5). The dissection is continued for at least the length of the mold without entering the peritoneal cavity. By cutting the median raphe, the two channels are then connected. If the dissection is performed in this manner, minimal bleeding is encountered. Any bleeding sites must be controlled meticulously to avoid lifting of the graft from the newly created vaginal wall and subsequent nonadherence and necrosis.

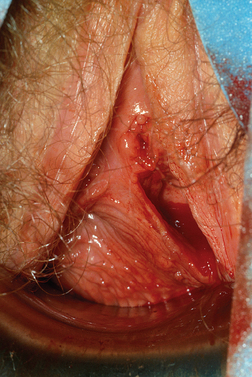

Figure 51-4 The initial transverse cut was made on the fibrous tissue and an initial space developed.

Figure 51-5 Placement of Hagar dilator to create space for the graft. The direction of the Hagar dilators is posterior.

After creation of the vaginal space, the mold covered with the skin graft is placed inside the cavity (Fig. 51-6). At the introitus, the skin graft is attached with several separate 3-0 absorbable stitches. To hold the mold in place, several loose nonreactive sutures such as 2-0 silk are used to approximate the labia minor in the midline.

Difficulty in dissecting the neovagina and increased probability of bleeding and fistula formation is encountered in the patient with a prior surgical procedure. Other problems that may be encountered include narrow subpubic arch, strong levators, shorter perineum, prior hymenectomy, and congenitally deep cul-de-sac.31

Because of concern regarding tissue necrosis from mold pressure and subsequent fistula formation, both rigid and soft molds have been used for this procedure (Figs. 51-7 and 51-8). Theoretically, soft molds decrease the risk of fistula formation that can result from avascular necrosis. A soft mold can be created by covering a foam rubber block with a condom.32 The foam is able to expand and fit the neovaginal space, thereby providing equal pressure throughout the canal. However, a report on the use of a rigid mold on 201 patients who underwent the McIndoe operation demonstrated a fistula formation rate of less than 1%.33 There is no study comparing the outcomes of soft versus rigid molds in this operation. Typically a rigid mold is used initially, but the patient is sent home with a soft mold in place.

An 80% success rate has been reported with this procedure.34 Because success rates are highest in those patients that have not undergone prior vaginoplasty, patients must be counseled extensively before surgery regarding the need for prolonged use of the mold. Indeed, part of the presurgical assessment involves determination of patient maturity and motivation concerning the use of dilators. Lack of compliance with postoperative use of dilators will lead to contracture and diminishment of vaginal length.

Surgical complications include postoperative infection and hemorrhage, failure of graft and formation of granulation tissue, and fistula formation. In general the incidence of complications are low: a rectal perforation rate of 1%, graft infection in 4%, and graft site infection of 5.5%.33 In a review of 50 patients, 2 rectovaginal fistulas and 1 graft failure were reported.31 Five patients required an additional operative procedure. Eighty-five percent of these patients considered their surgery to be a success.

Long-term data on the McIndoe procedure, although limited, consistently indicate an improvement in quality of life. In a series of 44 patients who underwent a surgical procedure to create the vagina, 82% achieved a functional satisfactory postoperative result.35 Vaginal length varied from 3.5 to 15cm. In another long-term study of women who underwent a McIndoe procedure, 79% of the patients reported improved quality of life, 91% remained sexually active, and 75% regularly achieved orgasm.36

The newly created vagina must be inspected at the time of the yearly pelvic examination and regular pap tests. Hair growth has been reported to be a problem with some skin grafts. Transformation to squamous cell carcinoma from skin graft has been described.37,38

Peritoneal Graft: Davydov Procedure

Use of the peritoneum to line the newly created vaginal space was popularized by Davydov, a Russian gynecologist, and first described by Rothman in the United States in 1972.39–41 In his original description, a laparotomy is performed after creation of the vaginal space, as described with the McIndoe operation.

A cut is made on the peritoneum overlying the new vagina. Long sutures are applied to the anterior posterior and lateral sides of this peritoneum. The sutures are then pulled down through the vaginal space, thus pulling the peritoneum to the introitus. The edge of the peritoneum is then stitched to the mucosa of the introitus. Closing the peritoneum on the abdominal side then forms the top of the vagina. Several investigators have also described the laparoscopic modification of this procedure.42–44

Adhesion Barrier Lining

Jackson first described the use of an adhesion barrier to line the neovagina in 1994.45 Oxidized regenerated cellulose (Interceed; Johnson and Johnson Patient Care Inc, New Brunswick, N.J.) forms a gelatinous barrier on raw surfaces and thus prevents adhesion formation. After creation of the vaginal space, sheets of clothlike oxidized regenerated cellulose are wrapped around the mold and placed in the vagina in a manner similar to the McIndoe. The neovaginal space must be free of any bleeding. Epithelialization is noted to occur within 3 to 6 months. Small areas of granulation tissue may be seen at the apex of the vagina and resolve after application of silver nitrate. Average vaginal depth ranges from 6 to 12cm. Continuous use of the mold is encouraged until complete epithelilization has occurred.

A case series assessed the outcome of this technique on 10 patients with vaginal agenesis.46 Complete squamous epithelialization was noted within 1 to 4 months. When compared to a normal vagina, fern formation was noted and the vaginal pH was always acidic. However, none of the women complained of vaginal dryness or foul-smelling discharge. Patients who were sexually active did not report any problems.

Amnion Lining

Amnion has also been used to line the neovagina cavity.47 Advantages include lack of a graft site, potential antibacterial effect, and lack of expression of histocompatibility antigens.48,49 Eight to 10 weeks after placement of amnion into the vaginal canal, the resulting epithelium was found to be “identical” to normal vaginal epithelium.50 However, concern about transmission of an infection with use of amnion has limited its use in the United States.

Muscle and Skin Flap

The use of gracilis myocutaneous flaps and rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps for vaginal reconstruction has been reported.51,52 This approach has been associated with a conspicuous scar and a higher failure rate. Wee and Joseph in Singapore designed flaps that maintained good blood supply and innervation.53 Known as a pudendal–thigh flap vaginoplasty, this technique has been particularly successful in patients with vulvar anomalies.54 In one study of patients with müllerian agenesis, 100% success in creating a functional vagina was reported.55

The patient’s own labia majora and labia minora have also been used to create a vagina.56 Tissue expansion has also been advocated to create labiovaginal flaps, which are then used to line the neovagina.57,58 Other modifications of this procedure have been reported.59,60

Bowel Vaginoplasty

Continuous use of dilators is not considered necessary, although constriction has been noted when ilium has been used. Success rates of up to 90% have been reported. Reported complications include profuse vaginal discharge, prolapse, introital stenosis, bowel obstruction, and colitis.61,62 Finally there is a report of a mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in a neovagina lined with the sigmoid colon.63

A laparoscopic modification of this procedure has also been described.64,65 Given the increased complication rates, it seems appropriate to reserve this treatment modality for complex situations where a prior vaginoplasty technique has failed or when there are multiple urogenital malformations.

OBSTRUCTED RUDIMENTARY UTERINE BULBS

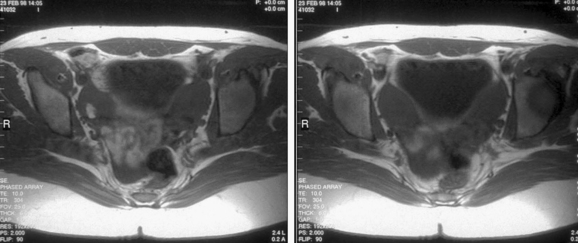

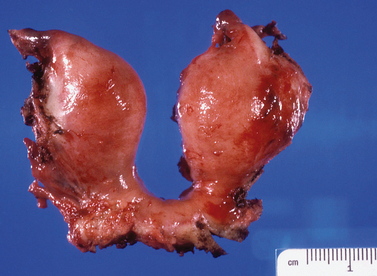

Patients with müllerian agenesis commonly have müllerian remnants noted on MRI or during a laparoscopy. The MRI has the added value of determining if any endometrial tissue exists within these remnants (Figs. 51-9 and 51-10). Patients with functional endometrial tissue may present after many asymptomatic years with cyclic pelvic pain secondary to monthly endometrial shedding, and development of endometriosis has been reported in these patients. Symptomatic müllerian bulbs should be removed either via laparotomy or laparoscopy.

CERVICAL AGENESIS

Cervical agenesis is a rare müllerian anomaly whose true incidence remains unknown despite many case reports in the literature.66 Various degrees of cervical abnormalities, ranging from dysgenesis to agenesis, have been described.67 The vagina may or may not be present in patients with cervical agenesis. In a series of 58 patients with cervical atresia, 48% had isolated congenital cervical atresia with a normal vagina.68 The rest of the patients had either a vaginal dimple or complete atresia.

Diagnosis

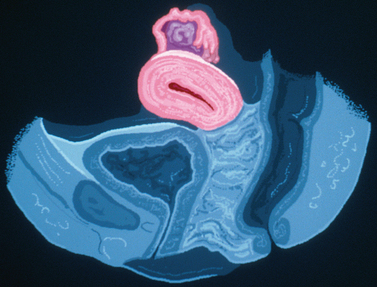

Unlike some of the other müllerian anomalies, patients with cervical agenesis present very early in adolescence. Typically, patients present between ages 12 and 16 with a primary complaint of pelvic pain secondary to obstruction of flow from the uterus. Initially, the pain is cyclic, but it may evolve with time into continuous pain. It is not uncommon for such patients to have been evaluated by their pediatricians for other causes of abdominal pain. Although these girls have amenorrhea, this symptom fails to raise a red flag because the patients are so young at presentation that lack of menses is not concerning. Continuing menstruation in an obstructed uterus forms a hematometra, and possibly hematosalpinx, endometriosis, and adhesions in the pelvis (Figs. 51-11 and 51-12).

Imaging of such a pelvis can easily lead to a misdiagnosis. Such patients have been taken to surgery for pain thought to be secondary to a pelvic mass, only to find that they have a congenital anomaly. Although ultrasound may be helpful in looking for a cervix, one’s clinical suspicion must be communicated directly to the radiologist performing the procedure. MRI is very helpful in visualizing the cervix and can accurately determine its presence or absence.69–71

Management

Surgical Approach

The other surgical options for management of cervical dysgenesis are cervical canalization or uterovaginal anastomosis. There are many reports in the literature of cervical canalization and stent placement.72–74 Although success has been reported with establishment of menses, many patients will require reoperation secondary to fibrosis of the cervical tract and obstruction. In addition, pregnancy rates are very low. In a review of patients with cervical agenesis, 59% of those that underwent cervical canalization achieved normal menstruation. Four of the 23 who achieved cervical patency required multiple surgeries.68 The task is even more daunting if there is also a vaginal anomaly that requires reconstruction.

There are several forms of cervical dysgenesis that are sometimes confused with agenesis.75 A hysterectomy may be considered in those patients with no evidence of a cervix, but canalization or uterovaginal anastomosis may be considered in those with a vagina and an obstructed cervix. Although preserving fertility is ultimately the goal of canalization procedures, sepsis and death have been reported subsequent to canalization.76 In addition, subsequent pregnancy rates are very low.73,77

The poor pregnancy rates may be attributed to several factors. Prolonged delay in diagnosis can lead to extensive endometriosis and scarring in the pelvis. Also, although canalization and stent placement may maintain an open pathway for menstruation, the lack of epithelization of the fistula not only increases the risk of fibrosis, but also may impede sperm migration into the uterus. The only pregnancy that was achieved in Rock’s series was one in whom a full-thickness skin graft was used in the canalized area.75 More recently the use of bladder mucosa to line the newly created cervical canal was reported.72

UTERINE FUSION DEFECTS

Correct diagnosis of these anomalies is of utmost importance, because their management varies significantly.78 The diagnosis is typically made based on evaluation of anatomy via imaging techniques, including ultrasonography, hysterosalpingography (HSG), and MRI or via laparoscopy and hysteroscopy. Although radiologic guidelines exist to differentiate these entities, the multitude varieties of these malformations can pose a significant challenge in making the correct diagnosis.

Septate Uterus

The management of uterine septum detected after an evaluation for recurrent pregnancy loss is hysteroscopic resection of the septum (see Chapter 43). However, the management of a septum found during an infertility investigation is less straightforward.78 Although the septum does not appear to cause infertility, the concern regarding possible spontaneous abortion after undergoing infertility treatment may be enough to justify hysteroscopic removal of the septum before infertility treatment.

On a historical note, in the distant past a uterine septum was sometimes removed along with the midline section of the uterus via laparotomy using a Jones or Tompkins metroplasty procedure. These relatively extreme approaches have been completely supplanted by hysteroscopic septoplasty, described in Chapter 43.

Bicornuate Uterus

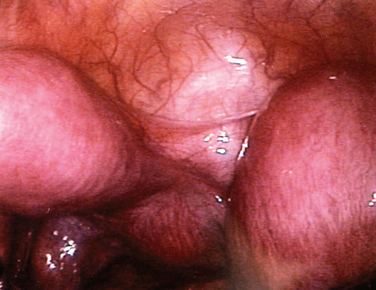

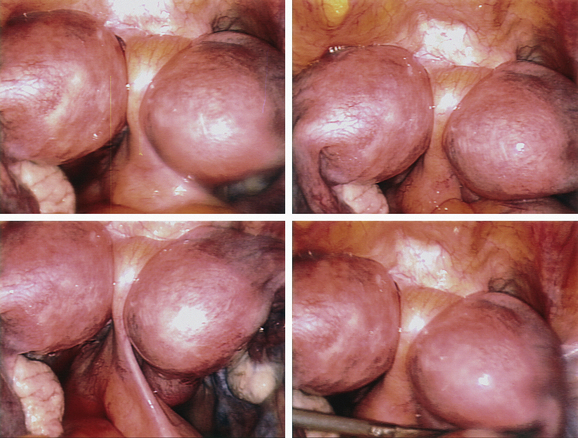

The most frequently diagnosed uterine malformation is the bicornuate uterus (Fig. 51-13).79 This anomaly is usually discovered incidentally during an investigation for infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss.

Figure 51-13 The appearance of a bicornuate uterus at laparoscopy. Note the peritoneal band between the two horns.

It is important to differentiate a bicornuate from a septate uterus. HSG alone cannot differentiate these entities, because this imaging approach cannot evaluate the external contour of the uterus. Laparoscopy was used primarily for this purpose in the recent past; modern imagining techniques, including ultrasonography and MRI, can adequately differentiate these two entities (see Chapter 31).

Imaging criteria to differentiate septate and bicornuate uteri have been developed.80,81 A septate uterus has a flat or convex fundus or a fundal indentation less than 10mm. The septum should be relatively thin, such that the angle between the medial borders of the hemicavities is smaller than 60 degrees. A bicornuate uterus has two distinct funduses with an intervening fundal indentation of at least 10mm. In most cases, the angle between the medial borders of the hemicavities will be greater than 60 degrees.

On MRI, a septate uterus will fail to show an intervening myometrium between the T2-hypointense septum that separates the endometrial cavities.80,81 In contrast, a bicornuate uterus will show two T2-hyperintense endometrial cavities, each with a junctional zone and myometrial band of intermediate signal intensity.

Conception does not appear to be a problem in women with bicornuate uterus.78 However, higher rates of preterm delivery (19%) and spontaneous abortion (42%) have been reported.82 Uteroplacental insufficiency and cervical incompetence may play roles in the higher obstetric complications. Thus, the treatment options for bicornuate uterus may include Strassman metroplasty and cervical cerclage. Because the benefit of metroplasty has never been established in a controlled study, it is typically considered only after multiple pregnancy losses and complications.83

Surgical Technique: Strassman Metroplasty

The Strassmann metroplasty is the procedure of choice in the uncommon case where unification of a bicornuate uterus is indicated.13 Via laparotomy, a transverse incision is made across the fundus of the bicornuate uterus. The opened cavity is then repaired in an anteroposterior fashion. Because the subsequent length of gestation appears to increase after each pregnancy loss in patients with a bicornuate uterus (due to myometrial stretching or unknown factors), metroplasty is always the procedure of last resort.

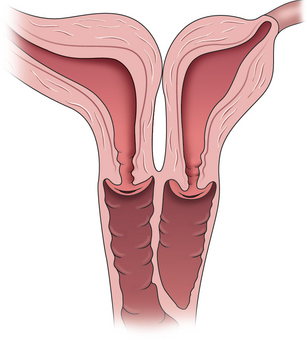

Didelphic Uterus

The didelphic uterus is defined as two completely separate uteri and cervices. It accounts for 10% of all uterine anomalies.79 On ultrasonography, the two bulbs of the uterus are distinctly noted and can be followed down to their individual cervices.

Surgical correction is not indicated. In a long-term follow-up of 49 patients with didelphic uteri, 89% of those desiring pregnancy had at least one living child.84 The spontaneous miscarriage rate was 21%, and only one ectopic pregnancy occurred. The most common problem was preterm delivery, which occurred in 24% of pregnancies. Fortunately, only 7% of the infants weighed less than 1500 gm at birth. Breech presentation was noted in 51% of the infants, and thus the cesarean section rate is increased.

UNICORNUATE UTERUS AND RUDIMENTARY HORN

A unicornuate uterus may be associated with a communicating or noncommunicating rudimentary horn. In either case, patients will have monthly regular periods. If a rudimentary horn is communicating or noncommunicating but nonfunctioning, the patient is unlikely to have severe dysmenorrhea. The diagnosis in these patients is usually made at the time of investigation for infertility, obstetric problems (including recurrent pregnancy loss), or at the time of cesarean section. In contrast, if a noncommunicating rudimentary horn is functioning, most patients will have severe dysmenorrhea unresponsive to medical therapy (Fig. 51-14).

Management

Management depends on whether the rudimentary horn is functional or communicating. A nonfunctioning, noncommunicating rudimentary horn does not need to be removed, as it will be asymptomatic and not put the patient at any risk. In contrast a functioning, noncommunicating rudimentary horn should be removed on diagnosis to alleviate the patient’s often severe dysmenorrhea and to avoid the risk of rupture, should a pregnancy occur in this horn.85

It would seem that a functioning, communicating rudimentary horn could be left in situ, since it is unlikely to be symptomatic for the patient. However, there is a risk of developing a pregnancy in such a horn, leading to subsequent rupture if undiagnosed.86 Therefore, surgical removal is recommended before attempting pregnancy.

Surgical Technique: Removal of a Rudimentary Horn

A rudimentary uterine horn can be removed via laparotomy or laparoscopy using similar techniques, depending on surgical experience.87 After gaining access to the pelvis, the round ligament of the rudimentary horn is identified, ligated, and divided. Access is gained into the retroperitoneal space, the ureter is identified, and the bladder is dissected off the lower border of the rudimentary horn.

The rudimentary horn may share myometrial tissue with the unicornuate uterus or be attached by a band of fibrous tissue.87,88 In cases where the uterine horn is attached to the uterus with a fibrous band, the blood supply is found within this band. Coagulation and transection of the band is all that is required.

LONGITUDINAL VAGINAL SEPTUM

The Nonobstructing Longitudinal Vaginal Septum

Nonobstructing longitudinal vaginal septa account for 12% of the malformations of the vagina. Although most are asymptomatic, some patients complain of continued vaginal bleeding despite placement of a tampon, difficulty removing a tampon, or dyspareunia. These septa may be complete or partial and can exist in any portion of the vagina (Fig. 51-15). The communication can be extremely small and a septum can easily be missed during physical examination, especially if there is a dominant vaginal canal.

Once the diagnosis is made, both the uterus and renal anatomy should be assessed for associated anomalies. In one study, 60% of patients with longitudinal vaginal septa were found to have a bicornuate uterus.89 Other investigators have noted a predominance of didelphic uteri in such cases.90

Some obstetricians advocate removal of a longitudinal vaginal septum before delivery to avoid potential dystocia and laceration of the septum.89 The number of patients with vaginal septa who have had successful vaginal deliveries remains unknown. However, emergent resection of a vaginal septum at the time of delivery to resolve dystocia has been reported.91 It seems reasonable to remove a thick longitudinal septum before pregnancy or before delivery if discovered during pregnancy.

The Obstructing Longitudinal Vaginal Septum

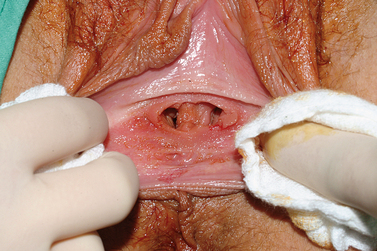

Women with an obstructing longitudinal septum usually present with normal-onset menarche and increasingly severe dysmenorrhea. These patients are most likely to have a didelphic uterus. One of the uteri has a patent outlet; the other is obstructed (Fig. 51-16).

If the obstruction is low in the vagina, eventually a bulge may be noted on examination of the lower canal. However, a higher obstruction may be completely missed with just visual inspection, which is frequently the case in an adolescent. Digital examination may reveal a tense bulge in the vaginal wall (Fig. 51-17). In many instances the bulge is found in the anterior portion of the vagina between the 12 o’clock and 3 o’clock positions or between the 9 o’clock and 12 o’clock positions due to the rotation of the two cervices.

Ultrasonography of the pelvis will usually show a pelvic mass, which can be misleading unless a vaginal septum is considered in the differential diagnosis. MRI is the best imaging mode for definitively diagnosing this abnormality. Like other müllerian anomalies, a longitudinal vaginal septum is associated with renal abnormalities, including absent kidneys, pelvic kidneys, and double ureters.92

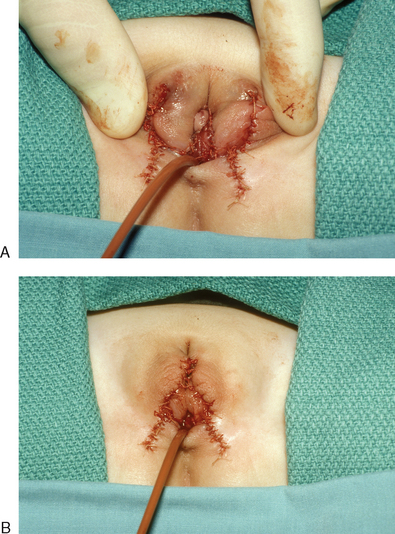

Surgical Technique

Accurate delineation of anatomy is a prerequisite for surgical excision of a noncommunicating longitudinal vaginal septum. The first step is to place a needle into the bulging vaginal wall to identify the correct plane of dissection. Once blood extrudes from the needle, the adjacent tissue is incised with electrocautery to gain access into the obstructed vagina. Allis clamps are placed on the edges of this incision and the cavity is assessed. When removing the medial border of this septum, care must be taken to avoid damaging the urethra and cervix. The septum should be removed in its entirety to allow easily access to the second cervix for Pap smears. The raw mucosal edges are approximated with 2-0 absorbable suture. Use of a vaginal moldafter surgery is not necessary, because postresection stenosis is rare. In difficult cases, use of either a resectoscope or hysteroscope to remove a longitudinal vaginal septum has been described.93,94

The previously hidden cervix and obstructed vaginal canal will often appear abnormal. The cervix is usually flush with the vaginal fornix and often appears erythematous and glandular. Histologically, the obstructed vaginal canal and septum on its obstructed side will have columnar epithelium and glandular cypts.92 Some patients may complain of profuse vaginal discharge after removal of the septum. Metaplastic transformation of the vaginal mucosa to mature squamous epithelium can take many years.

Simultaneous laparoscopy during removal of a vaginal septum is not recommended unless the diagnosis is unclear on MRI or imaging studies indicate concomitant pelvic masses. As in all cases of obstructive müllerian anomalies, endometriosis is frequently encountered, even if the septum is only partially obstucting.95,96 With the possible exception of endometriomas, excision of the endometriosis is not recommended because these lesions will regress after removal of the obstruction.95

The obstetric outcome of such patients is similar to that reported for patients with simple didelphic uterus. Pregnancy rates of 87% and live birth rates of 77% have been reported.92

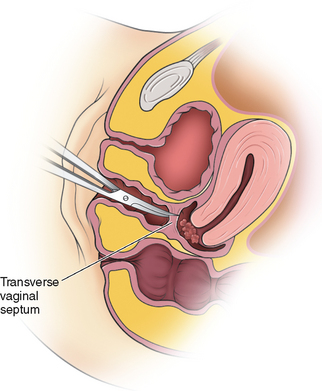

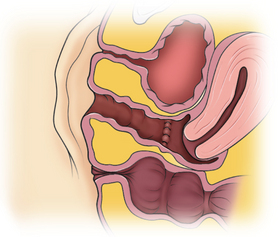

TRANSVERSE VAGINAL SEPTUM

The incidence of transverse vaginal septum appears to be between 1 in 21,000 to 1 in 72,000.67 A transverse vaginal septum may be located in the upper (46%), middle (40%), and lower (14%) third of the vagina.97,98 A transverse vaginal septum may be complete or incomplete and varies in thickness (Figs. 51-18 and 51-19).

Presenting Symptoms

Very rarely a transverse vaginal septum may be detected in an infant or young child. In such instances, a mucocolpos can present as an abdominal mass.67 If large enough, this mass may cause ureteral obstruction with secondary hydronephrosis. Compression of the vena cava and cardiopulmonary failure has also been reported.

Diagnosis

These patients should also be evaluated for associated anomalies, including aortic coarctation, atrial septal defects, urinary tract anomalies, and malformations of the lumbar spine.99

Surgical Technique

Delay in detection or treatment of a transverse vaginal septum may lead to impaired fertility secondary to irreversible pelvic adhesions, hematosalpinges, and endometriosis. In one long-term follow-up study of 19 patients with transverse septa, 47% became pregnant.99 However, a small study in Finland showed a significantly higher live birth rate in women who had undergone very early diagnosis and management of their transverse vaginal septa.100

An alternative to early surgery for very young patients is medical termination of monthly endometrial shedding using DMPA to postpone surgery.101 The young girl can be instructed to dilate the distal vagina to stretch the distal vaginal mucosa, potentially decreasing the need for a graft, and to prepare her for postoperative use of the dilator.

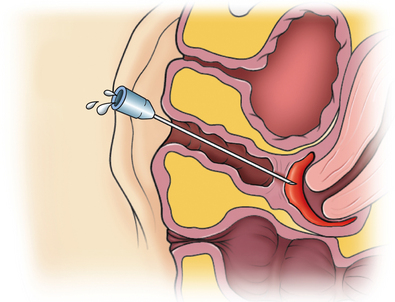

Surgical Technique: Thin Transverse Vaginal Septum

Transverse septa that are thin and low in the vagina can usually be excised without difficulty. If visually a slight bulge cannot be appreciated on examination, an angiocath needle is placed through the septum (Fig. 51-20). With return of thick blood through the angiocath, the plane of dissection becomes clear. Access is gained into the upper vaginal cavity by perforating a bulging transverse septum with unipolar electrosurgery or scissors (Fig. 51-21).

The septum is excised in its entirety and the upper vaginal mucosa is reapproximated to the lower vaginal mucosa using 2-0 absorbable suture (Fig. 51-22). In most instances, to prevent stenosis of the vagina, continual use of a mold is recommended for several weeks after surgery.

Surgical Technique: Thick Transverse Vaginal Septum

During surgery, a bulge will not be seen in the presence of a thick transverse septum. The correct angle of dissection can be determined by inserting an angiocath needle into the hematocolpos under ultrasound guidance. In difficult cases, the septum can be approached transfundally via the uterus using laparoscopy and laparotomy.67

Z-plasty Technique

If a thick septum is completely incised, the distance between the vaginal mucosa of the proximal and distal portions of the vagina may be so great that the edges cannot be reapproximated without tension. For this reason, a Z-plasty technique, as first described by Garcia and colleagues, should be considered for correction of thick transverse vaginal septa or when the vagina is short.102

For this technique, four lower mucosal flaps are created by making oblique crossed incisions through the vaginal tissue on the perineal side of the transverse septum, taking great care to avoid injuring either the bladder or rectum.103 Four upper mucosal flaps are created by making oblique crossed incisions through the vaginal tissue on the hematocolpos side of the transverse septum. The upper and lower mucosal flaps are separated by sharp and blunt dissection and sutured together at their free edges to form a continuous Z-plasty.

Excellent results have been noted on 13 patients who underwent this procedure.103 A vaginal mold must be used for 5 to 8 weeks after the procedure to avoid vaginal stenosis. If the girl is not sexually active, a dilator should be used at night for 6 to 8 additional months. The patient should be instructed in self-examination and should return if she notices any signs of early stenosis.

MANAGEMENT OF MALFORMATIONS OF THE EXTERNAL GENITALIA

Anomalies of the external genitalia are uncommon but require extreme skill in both surgical technique and patient interaction. The assignment of gender is a critical responsibility of a physician. Chapter 12 outlines the pathophysiology and patient approach in detail.

Gender Assignment and Timing of Surgery

Gender assignment and genital surgery for intersex patients remains controversial. Female genitoplasty performed in infancy can markedly complicate gender reassignment later in life. Gender dysphoria has been reported by some patients assigned a female gender of rearing based solely on anatomic considerations during infancy.104 This gender dysphoria may be due to androgen imprinting of the fetal brain. However, the true incidence of gender dysphoria in intersex patients is unknown.

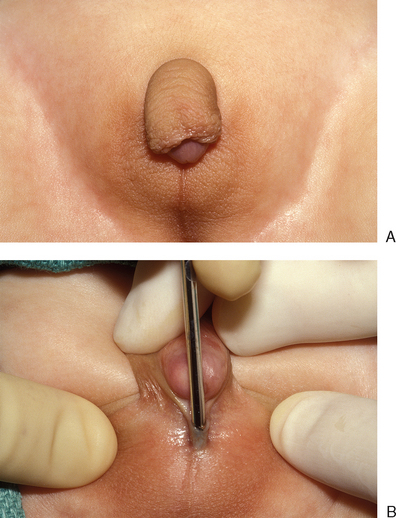

Clitoromegaly

Clitoromegaly in a newborn is an indication for a full intersex evaluation. Causes of clitoromegaly in a phenotypic female newborn include partial androgen insensitivity in XY individuals, mild congenital adrenal hyperplasia in XX individuals (Fig. 51-23), and a variety of other rare abnormalities. Therefore the first step in evaluating these patients is to determine the etiology of the clitoromegaly so that the primary problem may be addressed and appropriately managed.

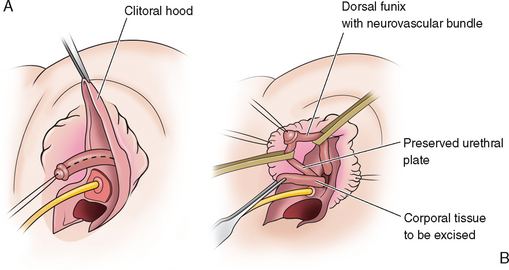

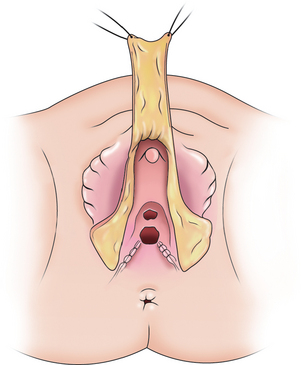

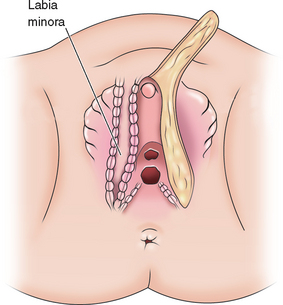

Surgical Technique: Reduction Clitoroplasty

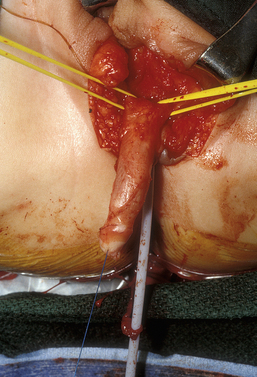

The first step in reduction clitoroplasty is to identify the vaginal opening. Next, a circumcision is performed and the phallus completely degloved (Fig. 51-24). The circumcision can be brought across the urethral plate at the base of the shaft, preserving this tissue, which can be used as an anterior flap in the vaginoplasty if desired.

Figure 51-24 A circumcision is performed and the phallus completely degloved. The Foley catheter is in the urethra and bladder.

The erectile tissue is then separated from the dorsal tunica vaginalis, on top of which run the neurovascular bundles (Fig. 51-25A). The erectile tissue is amputated at the crura and at the glans and excised, preserving the attachments of the dorsal tunica vaginalis and neurovascular bundles (Fig. 51-25B).

A dorsal slit is made in the dorsal hood and the apex of this incision secured to the dorsal midline of the glans edge with absorbable suture (Fig. 51-26). The skin flaps are then brought down on either side to recreate the labia minora (Fig. 51-27). The final result is shown in Figure 51-28.

Outcome Data

Several small retrospective studies of patients assigned a female gender undergoing feminizing genitoplasty as infants have found a high incidence of sexual dysfunction, loss of clitoral sensation, anorgasmia, and dissatisfaction with cosmesis.104–108 One small series of women born with ambiguous genitalia found that those who underwent clitoral surgery as infants had significantly more sexual problems than a comparable group who did not.105 Cosmetic outcome is often poor after clitoral surgery performed during infancy and reoperation later is usually required.106

Nerve-sparing procedures do not appear to fare much better. A study of 6 women who had undergone clitoral reduction as children with preservation of the neurovascular bundle found that each had markedly abnormal clitoral sensation.107,109 In another study of sexually active women who had undergone nerve-sparing reduction clitoroplasty as infants, 2 of 3 patients had the worst possible score for orgasm difficulties.

1 Buttram VCJr, Gibbons WE. Müllerian anomalies: A proposed classification. Fertil Steril. 1979;32:40-46.

2 Toaff ME, Lev-Toaff AS, Toaff R. Communicating uteri: Review and classification with introduction of two previously unreported types. Fertil Steril. 1984;41:661-679.

3 Acien P, Acien M, Sanchez-Ferrer M. Complex malformations of the female genital tract. New types and revision of classification. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2377-2384.

4 Jones HWJr. Reproductive impairment and the malformed uterus. Fertil Steril. 1981;36:137-148.

5 The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:944-955.

6 Aittomaki K, Eroila H, Kajanoja P. A population-based study of the incidence of müllerian aplasia in Finland. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:624-625.

7 Reindollar RH, Byrd JR, McDonough PG. Delayed sexual development: A study of 252 patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:371-380.

8 Fraser IS, Baird DT, Hobson BM, et al. Cyclical ovarian function in women with congenital absence of the uterus and vagina. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;36:634-637.

9 Petrozza JC, Gray MR, Davis AJ, Reindollar RH. Congenital absence of the uterus and vagina is not commonly transmitted as a dominant genetic trait: Outcomes of surrogate pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:387-389.

10 Strubbe EH, Cremers CW, Dikkers FG, Willemsen WN. Hearing loss and the Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Am J Otol. 1994;15:431-436.

11 Willemsen WN. Renal, skeletal, ear, and facial anomalies in combination with the Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster (MRK) syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1982;14:121-130.

12 Letterie GS, Vauss N. Müllerian tract abnormalities and associated auditory defects. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:765-768.

13 Buttram VCJr. Müllerian anomalies and their management. Fertil Steril. 1983;40:159-163.

14 Griffen JE, Creighton E, Madden JD, et al. Congenital absence of the vagina: The Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:224-236.

15 Frank RT. The formation of an artificial vagina without operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1938;35:1053-1057.

16 Committee on Adolescent Health Care. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Nonsurgical diagnosis and management of vaginal agenesis. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 274, July 2002. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;79:167-170.

17 Ingram JM. The bicycle seat stool in the treatment of vaginal agenesis and stenosis: A preliminary report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:867-873.

18 Roberts CP, Haber MJ, Rock JA. Vaginal creation for müllerian agenesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1349-1352.

19 Poland ML, Evans TN. Psychologic aspects of vaginal agenesis. J Reprod Med. 1985;30:340-344.

20 Weijenborg PT, ter Kuile MM. The effect of a group programme on women with the Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. BJOG. 2000;107:365-368.

21 Edmonds DK. Congenital malformations of the genital tract. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:49-62.

22 Robson S, Oliver GD. Management of vaginal agenesis: Review of 10 years practice at a tertiary referral centre. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40:430-433.

23 Costa EM, Mendonca BB, Inacio M, et al. Management of ambiguous genitalia in pseudohermaphrodites: New perspectives on vaginal dilation. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:229-232.

24 Vecchietti G. Neovagina nella sindrome di Rokitansky Küster-Hauser. Attual Obstet Gynecol. 1965;11:131-147.

25 Veronikis DK, McClure GB, Nichols DH. The Vecchietti operation for constructing a neovagina: Indications, instrumentation, and techniques. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:301-304.

26 Chatwani A, Nyirjesy P, Harmanli OH, Grody MH. Creation of neovagina by laparoscopic vecchietti operation. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1999;9:425-427.

27 Borruto F. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster syndrome: Vecchietti’s personal series. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1992;19:273-274.

28 Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanconato G, Raffaelli R. Laparoscopic creation of a neovagina in patients with Rokitansky syndrome: Analysis of 52 cases. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:384-389.

29 Borruto F, Chasen ST, Chervenak FA, Fedele L. The Vecchietti procedure for surgical treatment of vaginal agenesis: Comparison of laparoscopy and laparotomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;64:153-158.

30 Kaloo P, Cooper M. Laparoscopic-assisted Vecchietti procedure for creation of a neovagina: An analysis of five cases. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;42:307-310.

31 Buss JG, Lee RA. McIndoe procedure for vaginal agenesis: Results and complications. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:758-761.

32 Counseller VS, Flor FS. Congenital absence of the vagina. Surg Clin North Am. 1957;37:1107.

33 Alessandrescu D, Peltecu GC, Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA. Neocolpopoiesis with split-thickness skin graft as a surgical treatment of vaginal agenesis: Retrospective review of 201 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:131-138.

34 Hojsgaard A, Villadsen I. McIndoe procedure for congenital vaginal agenesis: Complications and results. B J Plastic Surg. 1995;48:97-102.

35 Mobus VJ, Kortenhorn K, Kreienberg R, Friedberg V. Long-term results after operative correction of vaginal aplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:617-624.

36 Klingele CJ, Gebhart JB, Croak AJ, et al. McIndoe procedure for vaginal agenesis: Long-term outcome and effect on quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1569-1572.

37 Hopkins MP, Morley GW. Squamous cell carcinoma of the neovagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:525-527.

38 Baltzer J, Zander J. Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the neovagina. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:99-103.

39 Davydov SN. [12-year experience with colpopoiesis using the peritoneum]. Gynakologe. 1980;13:120-121.

40 Davydov SN. [Colpopoeisis from the peritoneum of the uterorectal space]. Akush Ginekol (Mosk). 1969;45:55-57.

41 Rothman D. The use of peritoneum in the construction of a vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1972;40:835-838.

42 Soong YK, Chang FH, Lai YM, Lee CL, Chou HH. Results of modified laparoscopically assisted neovaginoplasty in 18 patients with congenital absence of vagina. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:200-203.

43 Templeman CL, Hertweck SP, Levine RL, Reich H. Use of laparoscopically mobilized peritoneum in the creation of a neovagina. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:589-592.

44 Rangaswamy M, Machado NO, Kaur S, Machado L. Laparoscopic vaginoplasty: Using a sliding peritoneal flap for correction of complete vaginal agenesis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98:244-248.

45 Jackson ND, Rosenblatt PL. Use of Interceed absorbable adhesion barrier for vaginoplasty. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:1048-1050.

46 Motoyama S, Laoag-Fernandez JB, Mochizuki S, et al. Vaginoplasty with Interceed absorbable adhesion barrier for complete squamous epithelialization in vaginal agenesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1260-1264.

47 Ashworth MF, Morton KE, Dewhurst J, et al. Vaginoplasty using amnion. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:443-446.

48 Akle CA, Adinolfi M, Welsh KI, et al. Immunogenicity of human amniotic epithelial cells after transplantation into volunteers. Lancet. 1981;2:1003-1005.

49 Robson MC, Krizek TJ. The effect of human amniotic membranes on the bacteria population of infected rat burns. Ann Surg. 1973;177:144-149.

50 Dhall K. Amnion graft for treatment of congenital absence of the vagina. BJOG. 1984;91:279-282.

51 Tobin GR, Day TG. Vaginal and pelvic reconstruction with distally based rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:62-73.

52 McCraw JB, Massey FM, Shanklin KD, Horton CE. Vaginal reconstruction with gracilis myocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:176-183.

53 Wee JT, Joseph VT. A new technique of vaginal reconstruction using neurovascular pudendal-thigh flaps: A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:701-709.

54 Joseph VT. Pudendal–thigh flap vaginoplasty in the reconstruction of genital anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:62-65.

55 Monstrey S, Blondeel P, Van Landuyt K, et al. The versatility of the pudendal thigh fasciocutaneous flap used as an island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:719-725.

56 Song R, Wang X, Zhou G. Reconstruction of the vagina with sensory function. Clin Plast Surg. 1982;9:105-108.

57 Belloli G, Campobasso P, Musi L. Labial skin-flap vaginoplasty using tissue expanders. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12:168-171.

58 Chudacoff RM, Alexander J, Alvero R, Segars JH. Tissue expansion vaginoplasty for treatment of congenital vaginal agenesis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:865-868.

59 Fliegner JR. A simple surgical cure for congenital absence of the vagina. Aust NZ J Surg. 1986;56:505-508.

60 Fliengrer JR. Congenital atresia of the vagina. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;165:387-391.

61 Parsons JK, Gearhart SL, Gearhart JP. Vaginal reconstruction utilizing sigmoid colon: Complications and long-term results. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:629-633.

62 Syed HA, Malone PS, Hitchcock RJ. Diversion colitis in children with colovaginoplasty. BJU Int. 2001;87:857-860.

63 Hiroi H, Yasugi T, Matsumoto K, et al. Mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in a neovagina using the sigmoid colon thirty years after operation: A case report. J Surg Oncol. 2001;77:61-64.

64 Darai E, Soriano D, Thoury A, Bouillot JL. Neovagina construction by combined laparoscopic-perineal sigmoid colpoplasty in a patient with Rokitansky syndrome. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:204-208.

65 Ota H, Tanaka J, Murakami M, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted ruge procedure for the creation of a neovagina in a patient with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:641-644.

66 Edmonds DK. Diagnosis, clinical presentation and mangement of cervical agenesis. In: Gidwani G, Falcone T, editors. Congenital Malformations of the Female Genital Tract: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:169-176.

67 Rock J, Breech L. Surgery for anomalies of the müllerian ducts. In: Rock JA, Jones HW3rd, editors. Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:705-752.

68 Fujimoto VY, Miller JH, Klein NA, Soules MR. Congenital cervical atresia: Report of seven cases and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1419-1425.

69 Letterie GS. Combined congenital absence of the vagina and cervix. Diagnosis with magnetic resonance imaging and surgical management. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:65-67.

70 Markham SM, Parmley TH, Murphy AA, et al. Cervical agenesis combined with vaginal agenesis diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Fertil Steril. 1987;48:143-145.

71 Reinhold C, Hricak H, Forstner R, et al. Primary amenorrhea: Evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;203:383-390.

72 Bugmann P, Amaudruz M, Hanquinet S, et al. Uterocervicoplasty with a bladder mucosa layer for the treatment of complete cervical agenesis. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:831-835.

73 Deffarges JV, Haddad B, Musset R, Paniel BJ. Utero-vaginal anastomosis in women with uterine cervix atresia: Long-term follow-up and reproductive performance. A study of 18 cases. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1722-1725.

74 Hovsepian DM, Auyeung A, Ratts VS. A combined surgical and radiologic technique for creating a functional neo-endocervical canal in a case of partial congenital cervical atresia. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:158-162.

75 Rock JA, Carpenter SE, Wheeless CR, Jones HW3rd. The clinical management of maldevelopment of the uterine cervix. J Pelv Surg. 1995;1:129-133.

76 Casey AC, Laufer MR. Cervical agenesis: Septic death after surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:706-707.

77 Jacob JH, Griffin WT. Surgical reconstruction of the congenitally atretic cervix: Two cases. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:556-569.

78 Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, et al. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:161-174.

79 Acien P. Incidence of müllerian defects in fertile and infertile women. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1372-1376.

80 Pui MH. Imaging diagnosis of congenital uterine malformation. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2004;28:425-433.

81 Krysiewicz S. Infertility in women: Diagnostic evaluation with hysterosalpingography and other imaging techniques. AJR. 1992;159:253-261.

82 Acien P. Reproductive performance of women with uterine malformations. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:122-126.

83 Patton PE. Anatomic uterine defects. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;37:705-721.

84 Heinonen PK. Clinical implications of the didelphic uterus: Long-term follow-up of 49 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;91:183-190.

85 Jayasinghe Y, Rane A, Stalewski H, Grover S. The presentation and early diagnosis of the rudimentary uterine horn. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1456-1467.

86 O’Leary JL, O’Leary JA. Rudimentary horn pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1963;22:371.

87 Falcone T, Hemmings R, Kalife R. Laparoscopic management of a unicornuate uterus with a rudimentary horn. J Gynecol Surg. 1995;11:105-107.

88 Falcone T, Gidwani G, Paraiso M, et al. Anatomic variation in the rudimentary horns of a unicornuate uterus: Implications for laparoscopic surgery. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:263-265.

89 Haddad B, Louis-Sylvestre C, Poitout P, Paniel BJ. Longitudinal vaginal septum: A retrospective study of 202 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;74:197-199.

90 Heinonen PK. Longitudinal vaginal septum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1982;13:253-258.

91 Carey MP, Steinberg LH. Vaginal dystocia in a patient with a double uterus and a longitudinal vaginal septum. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;29:74-75.

92 Candiani GB, Fedele L, Candiani M. Double uterus, blind hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis: 36 cases and long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:26-32.

93 Montevecchi L, Valle RF. Resectoscopic treatment of complete longitudinal vaginal septum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;84:65-70.

94 Tsai EM, Chiang PH, Hsu SC, et al. Hysteroscopic resection of vaginal septum in an adolescent virgin with obstructed hemivagina. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1500-1501.

95 Sanfilippo JS, Wakim NG, Schikler KN, Yussman MA. Endometriosis in association with uterine anomaly. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;154:39-43.

96 Stassart JP, Nagel TC, Prem KA, Phipps WR. Uterus didelphys, obstructed hemivagina, and ipsilateral renal agenesis: The University of Minnesota experience. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:756-761.

97 Rock JA, Zacur HA, Dlugi AM, et al. Pregnancy success following surgical correction of imperforate hymen and complete transverse vaginal septum. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59:448-451.

98 Lodi A. Contributo clinico stastico sulle malformazioni della vagina osservate mella. Clinica obstetricia e ginecologia di Milano dal 1906 al 1950. Ann Obstet Gynecol Med Perinatol. 1951;73:1246.

99 Rock JA, Zacur HA, Dlugi AM, et al. Pregnancy success following surgical correction of imperforate hymen and complete transverse vaginal septum. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59:448-451.

100 Joki-Erkkila MM, Heinonen PK. Presenting and long-term clinical implications and fecundity in females with obstructing vaginal malformations. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2003;16:307-312.

101 Hurst BS, Rock JA. Preoperative dilatation to facilitate repair of the high transverse vaginal septum. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1351-1353.

102 Garcia RF. Z-plasty for correction of congenital transverse vaginal septum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;99:1164-1165.

103 Wierrani F, Bodner K, Spangler B, Grunberger W. “Z”-plasty of the transverse vaginal septum using Garcia’s procedure and the Grunberger modification. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:608-612.

104 Nelson CP, Gearhart JP. Current views on evaluation, management, and gender assignment of the intersex infant. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2004;1:38-43.

105 Minto CL, Liao LM, Woodhouse CR, et al. The effect of clitoral surgery on sexual outcome in individuals who have intersex conditions with ambiguous genitalia: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2003;361:1252-1257.

106 Creighton SM, Minto CL, Steele SJ. Objective cosmetic and anatomical outcomes at adolescence of feminising surgery for ambiguous genitalia done in childhood. Lancet. 2001;358:124-125.

107 Crouch NS, Minto CL, Laio LM, et al. Genital sensation after feminizing genitoplasty for congenital adrenal hyperplasia: A pilot study. BJU Int. 2004;93:135-138.

108 Creighton S. Surgery for intersex. J R Soc Med. 2001;94:218-220.

109 Gearhart JP, Burnett A, Owen JH. Measurement of pudendal evoked potentials during feminizing genitoplasty: Technique and applications. J Urol. 1995;153:486-487.