CHAPTER 23 Surgical problems

Bile

For anatomical causes of obstruction see pages 131–3.

Functional gut obstruction can occur in babies in the following circumstances:

Sometimes bile is seen in aspirates when the feeding tube sits at or has passed through the pylorus — this can be confirmed on an abdominal X-ray. In an otherwise well baby, this can be fixed by pulling the tube back so that its tip lies in the body of the stomach.

Determining cause

Gastrointestinal perforation

The management of infants with gastrointestinal perforation should include:

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC)

There is a wide spectrum of clinical features in NEC. Signs can include feeding intolerance, vomiting, lethargy, temperature instability, abdominal distension, diarrhoea with or without frank blood, abdominal wall erythema and shock.

The Bell criteria are often used to classify the severity of the illness:

In general terms, large-bowel NEC is a much more benign illness than small-bowel NEC.

Gut obstruction — anatomical causes

Oesophageal atresia

Proximal bowel obstruction

Pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis is uncommon in neonates. It causes non-bile-stained ‘projectile’ vomiting.

Duodenal atresia

Duodenal atresia presents soon after birth with persistent vomiting, which is usually bile-stained.

Malrotation

Baby of mother with polyhydramnios

Delayed passage of meconium

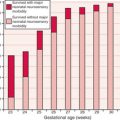

The normal time to passage of meconium increases with decreasing gestational age (GA).

Diagnosis

Always examine the perineum and anus carefully.

Gastroschisis

Therefore, the important aspects of the immediate management of a baby born with gastroschisis are: