Chapter 43 Surgical Management of Tumors of the Foramen Magnum

The foramen magnum (FM) comprises a bony channel formed anteriorly by the lower third of the clivus, the anterior arch of the atlas, and the odontoid process. The lateral limits are the jugular tubercle (JT), the occipital condyle (OC), and the lateral mass of the atlas. Lastly, the FM is limited posteriorly by the lower part of the occipital bone, the posterior arch of the atlas, and the two first intervertebral spaces.1–3

The FM encloses the vertebral arteries (VAs) and their meningeal branches, the anterior and posterior spinal arteries, the lower cranial nerves (IX, X, and XI), and the roots of the C1 and C2 vertebrae. The neural structures located at the FM are the cervicomedullary junction, the cerebellar tonsils, the inferior vermis, and the fourth ventricle.1–3 It is surrounded by veins, venous sinuses, and the jugular bulb. Hence, when approaching this region, surgeons must avoid manipulation and retraction of those neurovascular structures and, consequently, preserve anatomy and function.

There is a broad spectrum of intra- and extradural surgical pathologies of the FM. Tumors represent almost 5% of spinal and 1% of intracranial neoplasms,1 which consist mostly of meningiomas, neurinomas, and chordomas.1–5

In the past, these lesions were approached posteriorly and eventually via the transoral route; however, the results of these techniques were disappointing.6 The introduction of computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allowed the improvement of anatomic knowledge and the development of microsurgical techniques and skull base approaches. Therefore, treatment of these tumors has evolved and remarkable improvement in surgical results has been achieved. Nevertheless, despite these advances, surgery of FM tumors is still associated with a high rate of morbidity.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation associated with FM tumors is insidious. Because of their slow-growing pattern, their indolent behavior, and the wide subarachnoid space at this level, the mean length of symptoms before diagnosis is 30.8 months.3,7 In early stages, patients complain of occipital headache and cervical pain. This pain is described as deep and is aggravated by neck motion, coughing, and straining. As the tumor grows, sensory and motor deficits develop. The classic syndrome of FM tumors, mainly of meningiomas placed anteriorly, is an asymmetrical deficit defined by weakness, paresthesis, and spasticity, first in the ipsilateral arm and progressing to the ipsilateral leg, then to the contralateral leg, and finally to the contralateral arm. Long tract signs characteristic of upper-motor lesions are the presence of atrophy in the intrinsic muscles of the hands. Later findings include spastic quadriparesis, respiratory dysfunction, and lower cranial nerve deficits.6,7 In extradural tumors, especially in cranial base chordomas, diplopia is the symptom most commonly reported and headache is the second-most-common symptom.5

Classification of the Tumors

Tumors of the FM are classified according to their origin. They can arise in the FM itself or secondarily from surrounding areas. Most classifications focus on meningiomas and usually do not regard bone tumors. Among the many classifications of meningiomas of the FM,6–8 the one most frequently used by neurosurgeons is the classification from Bruneau and George.3 The main objective of this system is to define the surgical strategy preoperatively. Based on this classification, meningiomas of the FM are classified as intradural, extradural, or intra- and extradural. According to their insertion on the dura, meningiomas are anterior if insertion happens on both sides of the anterior midline, anterolateral if insertion occurs between the midline and the dentate ligament, or posterior if insertion is posterior to the dentate ligament. The other landmark used for classification is the relation to the VAs, because meningiomas of the FM can develop above, below, or on both sides of the VAs. Intradural meningiomas are the most common type, and most of them arise anterolaterally;4–8 these are followed in frequency by posterolateral tumors. Tumors that arise purely posteriorly and anteriorly are rare.7

The surgical approach to extradural tumors is based on their relationship with the C1 lateral mass, OC, clivus, intradural extension, cavernous sinus, jugular foramen, retropharynge, VAs, and carotid artery. Although there are various kinds of tumors, they present a similar surgical aspect. A position in front of, or lateral to, the cervicomedullary junction; a closer relationship with the VAs and their branches; lower cranial nerves; and complex articulation between the occipital bone and the C1 and C2 vertebrae are some of these surgical aspects. The size, position, and nature of the tumors define the surgical approach and steps, such as drilling the lateral wall of the FM and transposing the VAs. The definition of the space between the cervicomedullary junction and the lateral wall of the FM, the so-called surgical corridor,7 is also an important consideration. Large tumors, either anterior or anterolateral, push the cervicomedullary junction posteriorly, creating a surgical avenue for tumor removal. In contrast, small tumors and an elongated FM may require additional space, which can be obtained via the condyle or the lateral mass of C1, with transposition of the VAs.5

Preoperative Imaging

The preoperative workup includes MRI and CT scan. With the availability of CT angiography and magnetic resonance angiography, conventional angiography is rarely indicated unless embolization is planned in highly vascularized tumors. Preoperative imaging studies allow for planning of the surgery; for this, the following information must be retrieved from the images: the nature of the tumor (intra- and/or extradural), its location and attachment, its relationship with the cervicomedullary junction, its caudal and rostral extension, the position and possible involvement of the VAs and their branches, the shape of the FM, the dominance of the VAs, the venous drainage patterns and dominance, and bony involvement. T1-weighted MRI with contrast enhancement clearly defines the tumor and the dural attachment site and discriminates between the tumor and the brain stem. T2-weighted MRI provides information on the arachnoid plane between the tumor and the cervicomedullary junction. CT using sagittal, coronal, and axial viewing and bone window remains the tool of choice for the study of bone involvement, the shape of the FM, and the surgical corridor.1–3,6,7

Choosing the Best Approach

The principal factors that determine access to the lesions placed at the craniovertebral junction are the nature, position, and size of the tumors and the shape of the FM.5 Tumors located posteriorly or posterolaterally to the cervicomedullary junction can be approached from the posterior midline, which allows an extensive sagittal view from the skull base to the entire cervical spine; however, this approach does not work well for tumors located anterolaterally. This midline route does not allow control of the VAs when the bone needs to be removed ventrolaterally. Anterior approaches via transcervical or transoral routes have been used but are not accepted widely. The transoral approach is essentially a midline and extradural approach to the inferior clivus and upper cervical spine that, combined with maxillotomy or labiomandibulotomy and glossotomy, can provide access from the superior clivus to the middle cervical spine. Nevertheless, this approach is limited laterally from both carotid arteries and VAs at the clival and spinal levels. Removal of an intradural pathology carries a high risk of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. The dura is difficult to repair, because it comprises a limited amount of soft tissue and the subarachnoid space is exposed to the contaminated field.9 Anterior approaches are suitable for small extradural and bony lesions without VAs and carotid artery involvement.4,6,7,10

However, minimization of the cervicomedullary retraction and of risk of CSF leakage, a firm watertight closure, and management of the OC and of the VAs are the main factors considered when choosing the approach. Among the approaches available to the FM, the so-called far lateral approach, the extreme transcondylar approach, and its variants of the lateral suboccipital approach meet these criteria. These approaches can be combined with petrosal, retrosigmoid, transtuberculum, transfacetal, and infratemporal approaches, according to the rostrocaudal extension and nature of the tumor.6,11

Extradural tumors located frontal to the cervicomedullary junction that present with or without involvement of the VAs and the lower cranial nerves, that invade the dura, and that invade and/or destroy the OC and the articulation among OC, C1, and C2 can be approached via the same route; however, these tumors often require combined approaches.6,9–11

Far Lateral Approach

Positioning

Surgical results depend on the positioning of the patient. Malpositioning may result in a narrow microsurgical view, cerebral edema, increased bleeding because of impairment of venous return, and lesions of the eye, peripheral nerves, and spinal cord.12 At our institution, we adopt the three quarter–prone position to perform lateral approaches.6 The side of the approach is ipsilateral to the lesion. If the lesion is placed midline, the side of the approach is usually the side of the nondominant VAs and the nondominant jugular bulb. The body is placed in a lateral position, falling to the side of the craniotomy, and the arm contralateral to the operating side is placed out of the operating table and toward the floor and is padded with an axillary roll to avoid peripheral nerve damage. The knees and other pressure points are also padded to avoid damage to the peripheral nerves, and the legs are flexed to protect the femoral nerves. To avoid displacement of the patient’s body during operating table movements, adhesive tape is attached to the operating table and then applied at the hip and shoulder. The position of the head is crucial, as the surgeon needs good exposure of the occipitocervical region for a good angle of view of the contents of the posterior fossa. A three-point head holder is placed so that the mastoid bone is at the highest point of the approach. The neck should be slightly flexed and the vertex angled down, up to 30 degrees, with the face rotated slightly ventrally. The head should not be flexed more than two to three fingers from the thyroid and should not be rotated more than 45 degrees to prevent impairment of venous drainage. The results of this positioning are the cerebellum falling away from the operating field and the contents of the lateral aspect of the FM and posterior fossa being placed right under the surgeon’s view. Intraoperative monitoring is composed of somatosensory evoked potentials, auditory evoked responses, facial nerve monitoring, and monitoring of the X, XI, and XII cranial nerves, although their use is based on surgeon preference and acceptance.4,5,7,10

Skin Incision and Muscular Dissection

The skin flap is usually composed of the incised skin and galea, which are first elevated to expose the underlying pericranium. This structure, in addition to the superficial fascia of the neck, is elevated to expose the musculature of the posterior neck. The pericranium should be preserved to make a fascial graft for dural closure at the end of the operation. The first muscular layer that is exposed using this maneuver is composed by the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. They are incised near their insertion at the superior nuchal line and mastoid, leaving a cuff of tissue that is used later for closure of the incision. The underlying muscular layer (second or middle layer) is composed by the splenius capitis, longissimus capitis, and semispinalis capitis muscles. They are also incised and reflected as a single layer to expose the third layer, which forms the suboccipital triangle. The triangle is formed medially by the rectus capitis posterior major muscle, inferiorly by the inferior oblique muscle, and superolaterally by the superior oblique muscle; the VAs and its venous plexus are located in its center. Anatomic knowledge of the suboccipital triangle muscles and their insertions is essential to provide the best and safest exposure of the VAs. The rectus capitis major muscle inserts onto the inferior nuchal line and the spinous process of C2 and should be detached from the inferior nuchal line and reflected posteriorly. The inferior oblique muscle inserts onto the transverse process of C1 and onto the spinous process of C2 and the superior oblique muscle inserts at the inferior nuchal line and onto the transverse process of C1. Both muscles should be detached from the transverse process of C1 and reflected posteriorly. This maneuver exposes the C1 lamina, the VAs, the VAs venous plexus, and the C1 root.13

Knowledge of the muscular layers of the posterior neck is useful to prevent bleeding from the vascular structures of this region. Each muscular layer covers a vascular layer composed by a venous plexus and muscular arterial branches. Arterial blood supply for the muscles is provided by the occipital artery and by the muscular branches of the VAs. As the muscular branches of the VAs pass through the suboccipital triangle to reach the muscles, this is a crucial point for homeostasis. The main source of bleeding and air embolism in this region is the venous network. The venous system of the posterior neck is divided into two connected plexuses: (1) the suboccipital venous plexus and (2) the plexus around the VAs. The suboccipital venous plexus is superficial and is located in a space formed by the splenius capitis muscle superiorly and the longissimus capitis semispinalis capitis muscles inferiorly. The suboccipital plexus reaches the suboccipital triangle via the muscular cleft between the latter muscles and drains it into the plexus, thus surrounding the VAs through the anterior vertebral vein.14 Using the scalpel blade to cut through the muscles allows easier identification of these vascular layers and enables coagulation before bleeding and air embolism to occur.

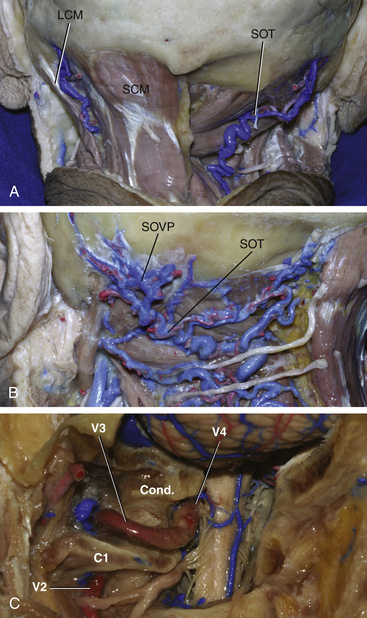

Exposure of the Extradural VAs

The VAs is divided into four segments. V1 is the segment that runs from the origin of the artery at the subclavian artery and ends at the vertebral foramen of C6. V2 runs within the vertebral foramina from C6 through C1. V3, which is the horizontal segment of the vessel, begins at the transverse foramen of the atlas, runs through a groove on the upper surface of the posterior arch of the atlas, and ends by piercing the dura of the posterior fossa, medial and to the right of the OC. V4 is the intradural segment of the VAs and joins the opposite side vessel to form the basilar artery13 (Fig. 43-1).

Exposure and transposition of the VAs is not needed in the basic far lateral approach, in which drilling of the OC is not required.15,16 To transpose the vessel in the other variations of the far lateral approach, dissection and manipulation of the venous plexus around the VAs, which is sometimes referred to as the suboccipital cavernous sinus, is needed. The suboccipital cavernous plexus is connected to the suboccipital plexus through the suboccipital triangle and via the anterior vertebral vein.4 It is also connected to the internal vertebral venous plexus, posterior and anterior condylar veins, and occipital marginal sinus. To avoid intense bleeding from the plexuses, subperiosteal detachment of the VAs from its groove in C1 is recommended. To transpose the VAs, unroofing of the C1 transverse process is also mandatory. After detachment of the VAs and plexus, laminectomy of the C1 arch as laterally as possible can be performed to expose the OC for drilling.1,2,4,5,10

The V3 segment of the VAs has some branches that need to be coagulated during the approach. The first and largest is the anterior VAs, which passes through the suboccipital triangle to reach the muscles of the posterior neck. The posterior meningeal artery is another branch that can be coagulated. Care should be taken not to coagulate a posteroinferior cerebellar artery (PICA) or a posterior spinal artery that arises extradurally from the V3.

Osseous Stage: Suboccipital Craniectomy and Hemilaminectomy

The landmarks for orientation of the craniotomy are (1) the asterion, (2) the midline, (3) the posterior border of the mastoid, (4) the inion, and (5) the superior nuchal line. The asterion is closely related to the lateral portion of the sulcus of the transverse sinus, especially with its inferior margin. To expose the lateral angle of the junction between the transverse and the sigmoid sinuses, a bur hole is placed immediately posterior and inferior to the asterion. This retrosigmoid point is the keyhole to the lateral suboccipital approach and exposes the posterolateral border of the cerebellar hemisphere.17 The inferior margin of the transverse sinus is located over a 50-mm line beginning at the inion and running across the superior nuchal line. This is the upper limit of the lateral suboccipital approach.

Condylar Stage

The OC, which is an oval-shaped osseous structure located at the base of the occipital bone, articulates the skull in relation to the cervical spine. The anterior portion of the condyle is directed anteriorly and medially toward the basion. The posterior portion ends at the level of the middle portion of the FM and blocks the angle of view to an anterior portion of the FM and of the craniovertebral junction. The resection of the posterior aspect of the condyle increases the angle of exposure, reduces brain stem retraction, and increases the working area of the posterior fossa.4–8,10,18,19 The presence of small anterior tumors, an elongated FM, a short distance between the foramen and the brain stem, and relatively large OCs represent the ideal conditions for resection of the condyle.20

A high-speed drill is used to remove the posterior portion of the condyle after displacement of the VAs to avoid injury of the vessel. The amount of condyle that can be safely removed is controversial; however, biomechanical studies showed that the removal of more than 50% of the condyle leads to considerable hypermobility of the craniocervical junction, in which case fusion is indicated.5,21 The removal of the cortical bone (which forms the external capsule of the condyle) exposes cancellous bone (which forms the core of the condyle). Drilling of this bone exposes the lateral aspect of the intracranial portion of the hypoglossal canal; this landmark is approximately at the limit of the posterior third of the condyle. Another maneuver that can be used to achieve a better view of the anterior portion of the clivus is the removal of the JT, a bony prominence situated above the hypoglossal canal, in cranial and medial extensions of the tumor.8,11

Many variants of the far lateral approach have been proposed, according to the amount of bony resection at the condylar region.4,5,10,18 The basic far lateral approach comprises the steps described earlier, without condylar drilling. An occipitoatlantal transarticular transcondilar approach is performed after the condyle and the C1 superior articular facet are removed. The occipital–transcondylar approach exposes the clivus and the lower medulla and is performed after drilling the atlanto-occipital joint, condyle, and lower border of the hypoglossal canal. A supracondylar variant increases the exposure of the lateral aspect of the clivus and is directed above the condyle. During the transtubercular approach, the JT above the hypoglossal canal is removed to expose the area in front of the lower cranial nerves. The paracondylar approach is achieved via drilling of the area lateral to the condyle to resect lesions of the jugular process and of the posterior aspect of the mastoid.5,11,13

Illustrative Cases

Patient 1

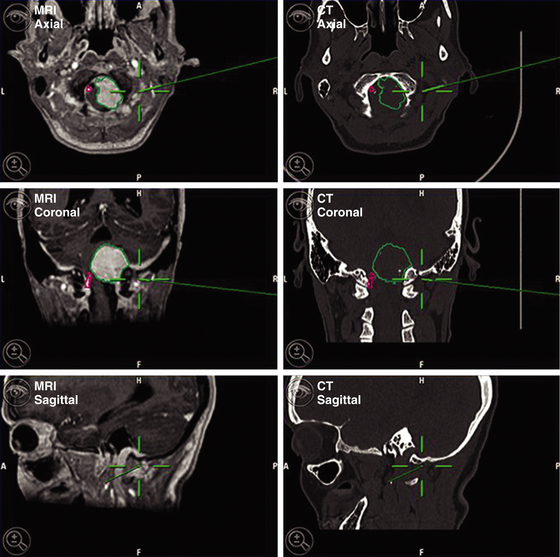

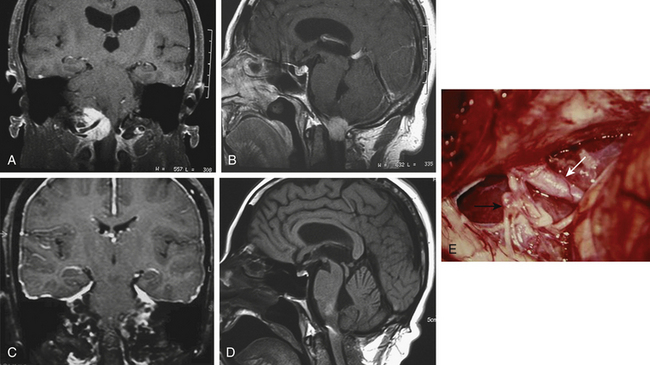

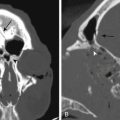

A 63-year-old woman presented with chronic upper neck pain, headaches, and neck stiffness. She also complained of weakness of the limbs. Thorough neurologic examination revealed hypotrophy of the tongue, tetrahyperreflexia, bilateral paresis of the trapezium, hypophonia, and left-palate deviation during phonation. MRI revealed the presence of a right anterolateral extramedullary tumor of the FM, with superior extension toward the jugular foramen and along the right hypoglossal canal, and development on both sides of the VAs. The tumor was hypointense on T1-weighted MRI and hyperintense on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and T2-weighted MRI, with homogenous enhancement after the infusion of gadolinium. CT angiography was performed to obtain relevant information on the VAs and the sigmoid sinus. CT with bone windows was also performed to assess the shape of the FM. Stereotactic image guidance was used. The surgical procedures were planned using an imaging database that included stereotactic CT and MRI scans (Fig. 43-2).

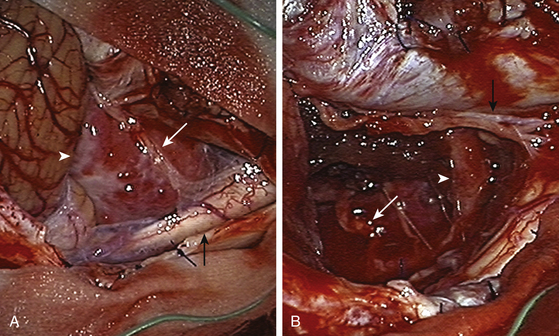

The tumor was resected using a far lateral suboccipital approach. The patient was placed in the three quarter–prone position, with the head fixed with a three-pin head holder (Fig. 43-3). Excessive superior shoulder traction was avoided. The head of the patient was tilted slightly downward to open the space between the mastoid and the neck. The incision ran laterally in an inverted hockey stick–shaped fashion, from the right mastoid process to the occipital protuberance, and then curved medially to the spinous process of C4. After exposure of the VAs (V2 to V3), a right far lateral suboccipital craniectomy was performed that included the rim of the FM. The JT was drilled because of the upward extension of the tumor. A right C1 hemilaminectomy without condyle resection was tailored. The dura was opened in a linear shape over the cerebellum, after identification of the VAs entry point. The next step consisted of draining the CSF by opening the cisterna magna. The procedure led to the spontaneous sinking of the cerebellum, which rendered significant retraction unnecessary. The dentate ligament was sectioned before the initiation of tumor removal and widening of the surgical corridor. A small portion of the V4 was identified before tumor involvement, and the dissection was performed by following the artery inside the tumor along an arachnoid plane. Microsurgical resection of a firm, consistent, and hypervascularized lesion with dural attachment was performed. The bulk of the tumor was removed using microscissors, cupped forceps, and an ultrasonic aspirator and was continued piecemeal. The tumor matrix was then coagulated, the basal dura was partially resected, and Simpson grade II resection was achieved. The only nerve that was identified initially was the spinal portion of cranial nerve XI and the posterior rootlets of the first cervical nerve. All of them were preserved. The other nerves and the VAs branches were identified during tumor removal. Control MRI and CT scan showed complete resection of the tumor (Figs. 43-4 and 43-5). After surgery, in the immediate postoperative period, videolaringoscopy showed that paresis of the lower cranial nerves worsened, providing evidence that a tracheostomy and gastrostomy were needed. The patient’s symptoms resolved, with the exception of some mild facial paresis and transient right brachial paresis (brachial plexus neuropraxis). Histopathologic analysis revealed the presence of a transitional meningioma.

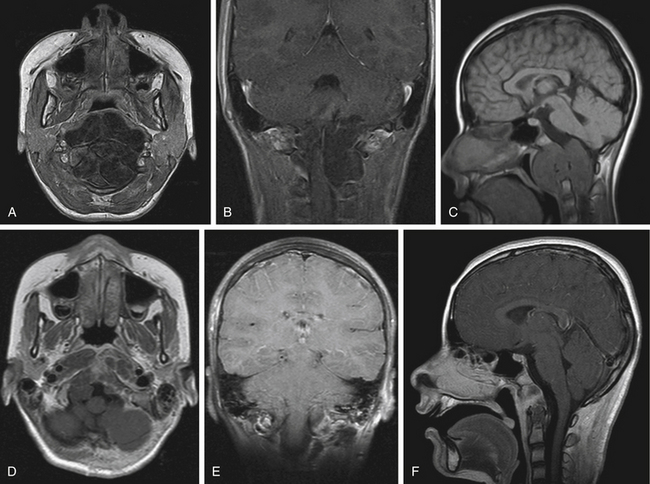

Patient 2

The patient was supposed to undergo follow-up; however, he did not comply in full, as he was afraid of a second surgery, which was recommended and necessary. Five years later, the patient returned because his symptoms had worsened. He was tetraparetic, in a wheelchair, and unable to stand up. In addition, he had dysphonia, dysphagia, and nocturnal apnea, with paralysis of the IX, X, XI, and XII cranial nerves, suggesting the presence of pyramidal-tract deficits and brain stem compression. Imaging revealed that the lesion had grown considerably and had infiltrated the medulla, engulfing the VAs. At that time, he finally accepted the second operation, as he had no other options. We started by performing a traqueostomy, as a fibroendoscopy examination showed that he had pulmonary microaspiration. He was reoperated on with complete monitorization of the affected neurologic functions and by using the same approach; however, we extended the surgery laterally and extradurally, as the tumor infiltrated the extradural portion of the VAs. The tumor was radically removed after we found an irregular and incomplete plane between the tumor and the brain stem. The postoperative period was uneventful. He recovered partially from his deficits, and at the last follow-up, he was able to stand up and walk, with the only remaining symptom being cranial nerve XII paresis (Fig. 43-6).

Patient 3

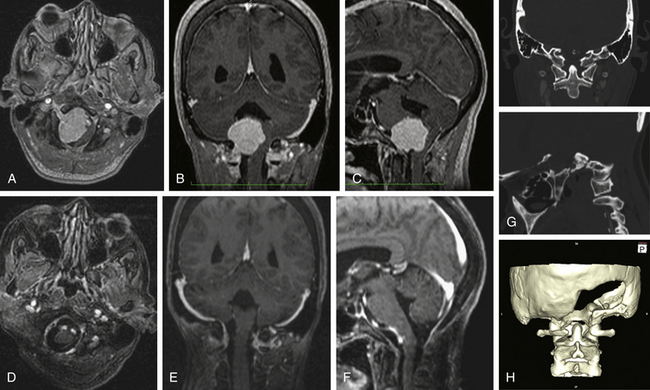

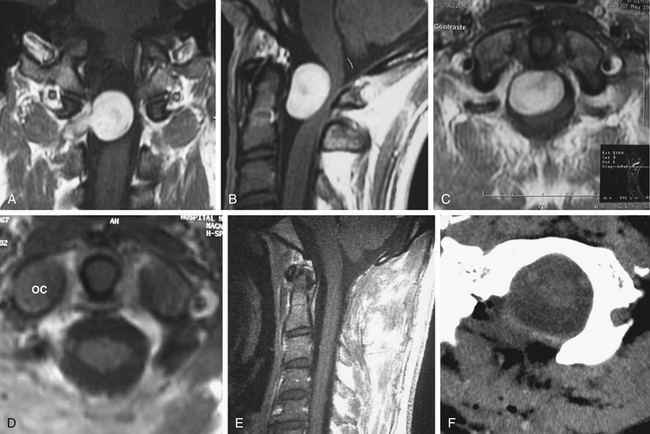

A 13-year-old girl presented with difficulty in swallowing and a severe occipital headache that was aggravated by physical activity. The symptoms started 15 months before examination. Neurologic examination was normal. MRI showed the presence of a widespread retropharyngeal tumor. The tumor involved both carotid arteries, displaced both VAs, and extended caudally to C3. The tumor seemed to replace the OCs bilaterally, as well as the arch of C1 and the inferior border of the clivus, from whence it invaded the subarachnoid space posterolaterally and ventrolaterally. CT showed intense bone involvement.

The second stage of the tumor resection was performed using the far lateral approach. A midline incision was performed because the tumor invaded the spinal canal bilaterally. Gross tumor resection was achieved that included part of the OC (on the right side) and the JT, with bilateral transposition of the VAs. The tumor that invaded the subarachnoid space was removed after careful dissection from the lower cranial nerves. A dorsal occipitocervical fusion was performed that spanned C1 and C2 and reached the fusion at the C3 or C4 level. Postoperatively, the patient exhibited swallowing deterioration; thus, gastrostomy and traqueostomy were performed. The traqueostomy was discontinued after the end of the third week after surgery, and the gastrostomy was discontinued after 3 months. Histopathologic examination revealed the presence of a chordoma. Postoperative MRI showed the presence of a residual mass, without compression (Fig. 43-7). The patient was able to return to her normal life and underwent MRI-based follow-up periodically.

Results

Our group of authors treated 22 patients with FM tumors. The mean age of the 14 women and eight men was 57.3 years. There were 12 meningiomas, all of them located intradurally and 10 arising from the anterior or anterolateral rim. One tumor was located in the posterior midline, and another had a posterolateral origin. One hypoglossal schwannoma had intradural and extradural components, and a C1 neurofibroma completed the intradural tumors in this series. Chordomas were the most common type of extradural tumors. The most common symptom was suboccipital neck pain and/or headache. Other symptoms included motor weakness, gait imbalance, myelopathy, and numbness. Table 43-1 lists the types of tumors, and Table 43-2 shows the clinical presentations of the patients in our cohort.

| Tumor Type | Patients |

|---|---|

| Meningioma | 12 |

| Schwannoma | 1 |

| Neurofibroma | 1 |

| Chordoma | 5 |

| Glomus tumor | 1 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 1 |

| Metastatic kidney carcinoma | 1 |

| Total patients | 22 |

TABLE 43-2 Clinical Presentation of Patients with FM Tumors

| Signs and Symptoms | Cases by Presented Symptom (Confirmed after Examination) |

|---|---|

| Suboccipital neck pain | 12 |

| Headache | 8 |

| Motor weakness | 9 (5) |

| Gait imbalance and myelopathy | 5 (2) |

| Numbness | 5 (6) |

| Cranial nerves | |

| Swallowing difficulty | 7 (5) |

| Tongue atrophy | 3 (2) |

| Speech problems | 3 (2) |

| Diplopia | 1 (2) |

| Hearing deficit | 1 (2) |

| Hand deficit | 1 (1) |

| Vomiting | 1 (1) |

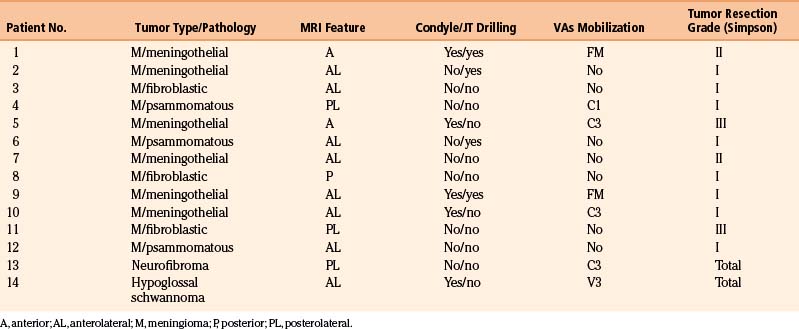

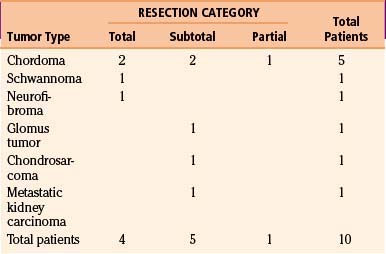

The posterior midline approach was performed in 2 patients with posterior and posterolateral meningioma, respectively. The far lateral approach was used in the other 10 patients. The rostrocaudal extension tailored the size of the craniotomy. For tumors with upward extension or located above the intracranial VAs, a combined retrosigmoid approach was performed in four cases and a petrosal approach was used in three cases, all of which had predominantly extradural tumors. An extended transoral–transpalatopharyngeal approach was used in two patients, both with chordomas. These patients required additional petrosal and far lateral transcondylar access. Drilling of the JT was performed in four cases that had FM meningiomas with cephalad extension. Partial resection of the lateral mass of C1 was performed in one patient with a C1 neurofibroma. The OC was partially resected in three patients with meningioma and in one patient with hypoglossal schwannoma (Table 43-3).

For intradural tumors, the VAs was mobilized in five cases, although it was encased or displaced in all cases. This maneuver was performed at the dural entry of the artery at the FM. For extradural tumors, the VAs was encased in four patients with chordomas, and it was displaced in another four patients. In extradural tumors, the VAs was mobilized in all cases, either for dissection or for improved exposure. In these cases, the VAs was transposed at the C1 transverse foramen and mobilized medially. There were no injuries in the VAs, neither in extradural nor in intradural tumor cases.

The grade of tumor resection for intradural tumors was based on Simpson’s classification.21 For nonmeningiomas, the degree of resection was divided into three categories: (1) total resection, in which the entire tumor was removed; (2) subtotal resection, in which a small fragment of the tumor remained on vital structures, such as the VAs, cranial nerves, or the brain stem; (3) partial resection, in which the bulk of the tumor remained.5

For meningiomas, radical excision (Simpson grades I and II) was achieved in 10 cases (83.3%). In most cases, the dura insertion was coagulated or removed. Two patients had Simpson grade III resection. The incomplete resection performed in one patient was attributable to a firm adhesion of the lower cranial nerves to the VAs and poor dissection planes; in another patient, intentional decompression was planed because of the clinical condition. Other patients underwent two surgeries (see the illustrative case of patient 2). The patient with hypoglossal schwannoma had a total resection, and the patient with a dumbbell-shaped neurofibroma of C1 had total tumor removal via a transfacetal approach (Fig. 43-8).

Total resection was achieved in two cases of chordoma tumors; the remaining three patients had a partial removal because of the extensive nature of the tumor, which occupied multiple compartments, invaded the jugular foramen and the cavernous sinus, and encased the carotid arteries. The patient with chondrosarcoma also had partial tumor removal because of the firm adherence to the lower cranial nerves (Table 43-4).

Comments

Surgical treatment is the best approach to treat tumors of the FM, especially meningiomas, schwannomas, neurofibromas, and chordomas. Most lesions can be removed using posterior approaches; however, when the tumors are located anteriorly or anterolaterally, resection using traditional approaches becomes more difficult. Some authors used posterior approaches to reach posterolateral and anterolateral tumors located at the FM,22,23 as large tumors provide a working space that is sufficient for resection of the tumor. However, there is not enough space to control the VAs between C2 and C3 and to reach essential anterior midline and small tumors.

Intradural extramedullary tumors, which are located anterolaterally or ventrally and are mostly meningiomas, generally tend to extend cranially and caudally. For this reason, and to obtain sufficient exposure of the cervicomedullary junction, tumor interface, rostrocaudal extension, and attachment at the dura, as well as to achieve dissection of the lower cranial nerves and control of the VAs and their branches, approaches that are more lateral are required. Among them, the far lateral approach and its variants, such as the transcondylar, transtubercle, and transfacetal methods, met the criteria. Resection or drilling of the condyle posterior to and below the hypoglossal canal provides an enhanced view of the target area. The extreme lateral transcondylar approach, which implies drilling the condyle, was used by some neurosurgeons.4–6,8,9,24 This procedure is not required for most intracranial tumors because there is risk of vertebral artery injury.16

Transposition of the VAs is another controversial point. Injury of this vessel or transposition of atherosclerotic VAs may result in permanent or transient neurologic deficit.16 For intradural tumors in patients with a normal VAs, the artery can be mobilized at the dural entry but not transposed posteromedially, because this implies drilling the condyle and unroofing the transverse foramen of C1. For patients with extradural tumors, resection of the condyle is not as controversial; in such patients, drilling the bone is part of the surgical treatment.5,10

Incomplete resection is a challenge for neurosurgeons. The size and the rostral extension from the tumor to the midline of the clivus are factors that influence morbidity.24 Remnants of tumors with strong adherence to the brain stem or to the VAs and their branches should not be resected. We prefer to follow the patient periodically instead of sending the patient to radiation therapy because of the risk of complications and because a second procedure would be more difficult.5,16,25

Bassiouni H., Ntoukas V., Asgari S., et al. Foramen magnum meningiomas: clinical outcome after microsurgical resection via a posterolateral suboccipital retrocondylar approach. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1177-1187.

Boulton M.R., Cusimano M. Foramen magnum meningiomas: concepts, classifications, and nuances. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14(6):10.

Bruneau M., George B. Foramen magnum meningiomas: detailed surgical approaches and technical aspects at Lariboisiére Hospital and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2008;31:19-33.

George B.. Foramen magnum tumors, Shmidek H.H., Roberts D.W. Schmidek and Sweet. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results, 5th ed., Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

Gupta S.K., Khosla V.K., Chhabra R., et al. Posterior midline approach for large anterior/anterolateral foramen magnum tumors. B J Neurosurg. 2004;18(2):164-167.

Margalit N.S., Lesser J.B., Singer B.A., Sen C. Lateral approach to anterolateral tumors at the foramen magnum: factor determining surgical procedure. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(ONS suppl 2):ONS-324-ONS-326. pp. 324-336

Menezes A.H. Surgical approaches: postoperative care and complications “posterolateral–far lateral transcondilar approach to the ventral foramen magnum and upper cervical spinal canal”. Childs Nerv System. 2008;24:1203-1207.

Rhoton A.L.Jr. The posterior cranial fossa: microsurgical anatomy & surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(suppl 3):S131-S153.

Roberti F., Sekhar L.N., Kalavaconda C., et al. Posterior fossa meningiomas: surgical experience in 161 cases. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:8-21.

Salas E., Sekhar L.N., Ziyal I.M., et al. variations of extreme-lateral craniocervical approach: anatomical study and clinical analysis of 69 patients. J Neurosurg (Spine 2). 1999;90:206-219.

Wanebo J.E., Chicoine M.R. Quantitative analysis of the transcondylar approach to the foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:934-943.

1. George B.. Foramen magnum tumors, Shmidek H.H., Roberts D.W. Schmidek and Sweet. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results, 5th ed., Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005. pp. 1755-1765

2. George B., Lot G. Anterolateral and posterolateral approaches to the foramen magnum: technical description and experience from 97 cases. Skull Base Surg. 1995;5:9-19.

3. Bruneau M., George B. Foramen magnum meningiomas: detailed surgical approaches and technical aspects at Lariboisiére Hospital and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2008;31:19-33.

4. Arnautovic K., Al-Mefty O., Husain M. Ventral foramen magnum meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:71-80.

5. Margalit N.S., Lesser J.B., Singer B.A., Sen C. Lateral approach to anterolateral tumors at the foramen magnum: factor determining surgical procedure. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(ONS suppl 2):ONS-324-ONS-326.

6. David C.A., Spetzler R.F. Foramen magnum meningiomas. Clin Neurosurg. 1997;44:467-490.

7. Boulton M.R., Cusimano M. Foramen magnum meningiomas: concepts, classifications, and nuances. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14(6):10.

8. Borba L.A.B., Oliveira J.G., Giudicissi-Filho M., et al. Surgical management of foramen magnum meningiomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2009;32:49-60.

9. Miller E., Crockard H.A. Transoral transclival removal of anteriorly placed meningiomas at foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:966-968.

10. Roberti F., Sekhar L.N., Kalavaconda C., et al. Posterior fossa meningiomas: surgical experience in 161 cases. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:8-21.

11. Salas E., Sekhar L.N., Ziyal I.M., et al. variations of extreme-lateral craniocervical approach: anatomical study and clinical analysis of 69 patients. J Neurosurg (Spine 2). 1999;90:206-219.

12. Rozet I., Vavilala M.S. Risks and benefits of patient positioning during neurosurgical care. Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;3:631-653.

13. Rhoton A.L.Jr. The posterior cranial fossa: microsurgical anatomy & surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(3 suppl):S131-S153.

14. Reis C.V., Deshmukh V., Zabramski J.M., et al. Anatomy of the mastoid emissary vein and venous system of the posterior neck region: neurosurgical implications. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(suppl 2):193-200. discussion 200–201

15. Nanda A., Vincent D.A., Vannemrredy P.S.S.V., et al. Far-lateral approach for intradural lesions of the foramen magnum without resection of the occipital condyle. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:302-309.

16. Bassiouni H., Ntoukas V., Asgari S., et al. Foramen magnum meningiomas: clinical outcome after microsurgical resection via a posterolateral suboccipital retrocondylar approach. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1177-1187.

17. Ribas G.C., Yasuda A., Ribas E.C., Nishikuni K., Rodrigues A.J.Jr. Surgical anatomy of microneurosurgical sulcal key points. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(suppl 4):ONS-177-ONS-210.

18. Menezes A.H. Surgical approaches: postoperative care and complications “posterolateral–far lateral transcondilar approach to the ventral foramen magnum and upper cervical spinal canal”. Childs Nerv System. 2008;24:1203-1207.

19. Pamir M.N., Kilic T., Ozduman K., et al. Experience of a single institution treating foramen magnum meningiomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11(8):863-867.

20. Wanebo J.E., Chicoine M.R. Quantitative analysis of the transcondylar approach to the foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:934-943.

21. Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22-39.

22. Gupta S.K., Khosla V.K., Chhabra R., et al. Posterior midline approach for large anterior/anterolateral foramen magnum tumors. B J Neurosurg. 2004;18(2):164-167.

23. Goel A., Desai K., Muzumdar D. Surgery on anterior foramen magnum meningiomas using a conventional suboccipital approach: a report on an experience with 17 cases. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:102-107.

24. Kano T., Kawase T., Horiguchi T., Yoshida K. Meningiomas of ventral foramen magnum and lower clivus: factors influencing surgical morbidity, the extent of tumor resection, and tumor recurrence. Acta Neurochir. Sep 25, 2009.

25. Ganz J.C., Reda W.A., Abdelkarim K. Adverse radiation effects after gamma knife surgery in relation to dose and volume. Acta Neurochir. 2009;151:9-19.