Chapter 169 Surgical Incisions, Positioning, and Retraction

A variety of ventral and dorsal incisions are used to gain access from the upper cervical to the lower sacral spine. Appropriate positioning plays an important role in minimizing blood loss and providing adequate exposure of the spine. Tissue retraction plays an equally important role. Table 169-1 presents an overview of approaches and corresponding incisions. This chapter focuses on surgical decisions, patient positioning, and retraction techniques to avoid complications during surgery.

TABLE 169-1 Classification of Surgical Approaches and Commonly Used Incision Types

| Region | Exposure | Incision |

|---|---|---|

| High Cervical Spine | ||

| Dorsal approaches | Suboccipital craniectomy C1–2 laminectomy | Dorsal midline |

| Lateral transcondylar approach | Hockey-stick, retromastoid | |

| Ventral approaches | Transoral approach | Midline pharynx |

| Median labiomandibular glossotomy | Median lower lip, mandible, tongue | |

| Transthyroidal approach | Transverse below hyoid bone | |

| Ventrolateral retropharyngeal approach | T-shaped submandibular or hockey-stick | |

| Lateral approaches | SCM may be cut | L-shaped incision below mastoid process |

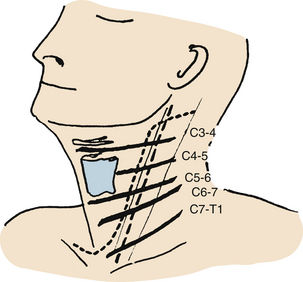

| Subaxial Cervical Spine (C3-T1) | ||

| Dorsal approaches | Laminoforaminotomy for cervical disc disease | Dorsal paramedian |

| Laminectomy | Dorsal midline | |

| Laminoplasty | Dorsal midline | |

| Ventral approaches | Ventromedial approach | Parallel to skin crests or SCM |

| Ventrolateral approach–medial to the carotid artery | Parallel to SCM | |

| Ventrolateral approach–lateral to the carotid artery | Parallel to SCM | |

| Cervicothoracic Junction (C7-T3) | ||

| Dorsal approaches | Laminectomy | Dorsal midline |

| Ventral approaches | Lower ventral-medial cervical approach | Parallel to SCM |

| Transsternal approach | T-shaped; extending midsternum | |

| Transmanubrial approach | T-shaped; or parallel to SCM extending midsternum | |

| Transverse supraclavicular approach | Parallel to clavicle | |

| Transaxillary extrapleural approach | Subaxillary, parallel to T3 rib | |

| Transpleural-transthoracic approach | Parallel to T3 rib | |

| Thoracic and Thoracolumbar Spine | ||

| Dorsal approaches | Thoracic laminectomy | Dorsal midline |

| Transpedicular approach | Dorsal midline | |

| Costotransversectomy | Curved to one side paramedian | |

| Lateral extracavitary approach | Curved to one side paramedian or hockey-stick | |

| Dorsal en bloc total spondylectomy | Dorsal midline | |

| Ventral approaches | Transpleural thoracotomy | Parallel to rib |

| Transdiaphragmatic approach | Flank incision | |

| Ventrolateral retroperitoneal approach | Flank incision | |

| Lumbar and Lumbosacral Spine | ||

| Dorsal approaches | Lumbar laminectomy | Dorsal midline |

| Paraspinal approach | Paramedian | |

| Lateral extracavitary approach | Paramedian | |

| Ventral approaches | Extreme lateral interbody fusion approach or ventrolateral transpsoatic approach | Lateral lumbar |

| Pelvic brim extraperitoneal approach | Lower flank incision | |

| Transperitoneal approach | Midline/horizontal subumbilical laparotomy incision | |

| Sacrum | ||

| Dorsal approaches | Dorsal approach | Dorsal midline |

| Ventral approaches | Retroperitoneal approach | U-shaped suprapubic incision |

| Transperitoneal approach | Midline subumbilical laparotomy incision | |

SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle.

Patient Positioning

Sitting Position

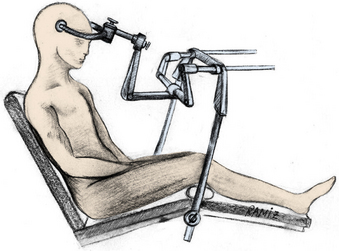

An advantage of the sitting position is that it directs blood away from the surgical site (Fig. 169-1). The risk of air embolism, however, is a major disadvantage. Furthermore, if the patient is quadriplegic (with a decrease in sympathetic tone), the resulting hemodynamic changes and hypoperfusion associated with the sitting position may compromise the perfusion of the spinal cord. Therefore, the sitting position requires a competent anesthetist as well as right atrial and pulmonary artery catheterization, Doppler ultrasound heart monitoring, and end-tidal CO2 monitoring.

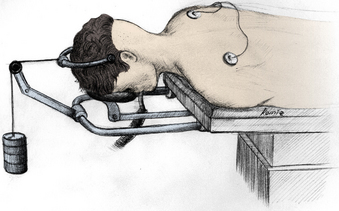

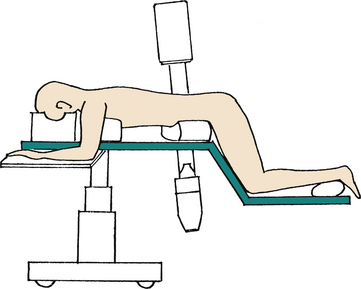

Lateral Approaches

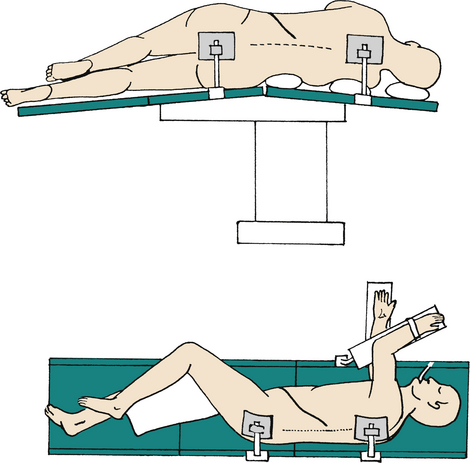

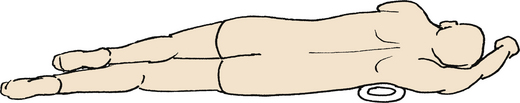

In the lateral decubitus position, the table may either be neutral or slightly extended to extend the rib cage. In this position, care should be taken to avoid compression of the brachial plexus; therefore, a roll should be placed under the axilla. The upper arm should be abducted no more than 90 degrees. The elbow must be properly padded (Fig. 169-2).

Retractors

Transoral Retractors

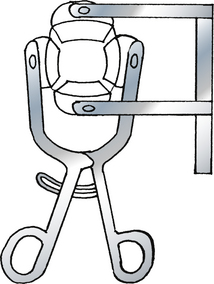

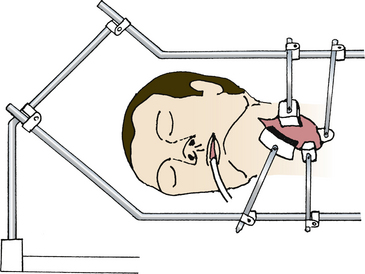

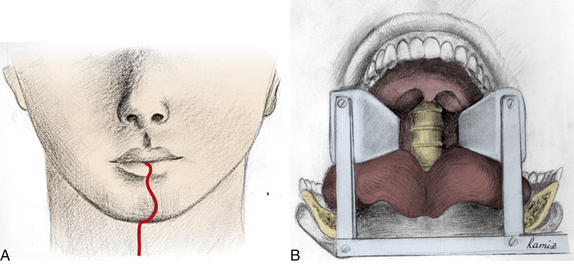

Self-retaining retractors are usually necessary to maintain an open mouth and to depress the tongue. Self-retaining retractor rings are fixed on the upper and lower teeth (Fig. 169-3). Table-mounted retractors are attached to the operating table to retract both the palate and the tongue. These retractors may also hold the neck in a fixed position; thus, they may eliminate the need for additional skeletal traction.

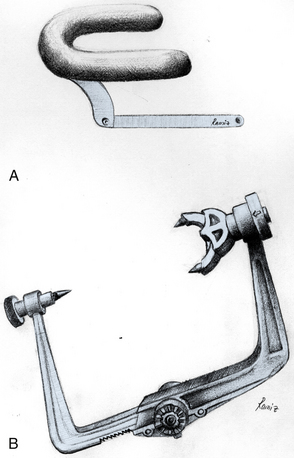

Ventral Cervical Retractors

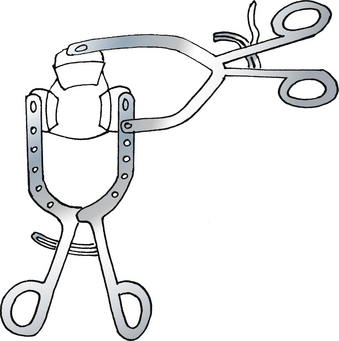

Hand-held retractors with blunt tips are useful for the dissection phase of the operation. For subsequent phases of ventral cervical operations, the most commonly used self-retaining retractors are the Caspar (Aesculap, Tuftlingen, Germany; Fig. 169-4), Apfelbaum (Aesculap; Fig. 169-5), Cloward (Codman, Raynham, MA), and Farley-Thompson retractors (Thompson Surgical Instruments, Traverse City, MI; Fig. 169-6).

A modified Caspar retractor has been recommended for ventrolateral foraminotomy; it enables retraction of the longus colli muscle laterally and facilitates vertebral artery retraction.1

Ventral Thoracic and Lumbar Retractors

A crank-type retractor is useful to distract the ribs. The lungs as well as the diaphragm or retroperitoneal organs are retracted with lung and abdominal hand-held retractors. Although they may narrow the operating space, the placement of laparotomy sponges under retractor blades helps to prevent damage to the viscera. The disadvantages of hand-held retractors include the risks of visceral organ damage and the difficulty of manually maintaining sufficient retraction force. Table-mounted systems retract both the rib cage and the lungs.

Dorsolateral Thoracic and Lumbar Retractors

The lateral extracavitary approach to the thoracic and lumbar spine requires significant retraction. A rostral and caudal self-retaining tissue-mounted retractor may be used to medially retract the paraspinous muscles. A wide-diameter, malleable retractor can be used to laterally retract the muscles of the chest wall or the lumbodorsal muscles. Either hand-held or table-mounted retractors may be used.2

Approaches

Dorsal Approaches to the Upper Cervical Spine

Midline Dorsal Approach

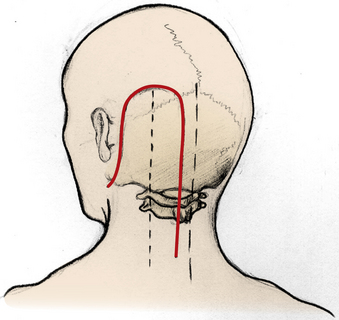

Either the sitting or the prone position can be used in a midline dorsal approach. If skull traction is required, the prone position with a horseshoe attachment should be considered (Figs. 169-7 and 169-8).

Two deep-seated self-retaining retractors are usually satisfactory. Menezes recommends using two retractors placed at 90 degrees to each other to prevent motion of the occipitocervical and atlantoaxial joints.3

Lateral Transcondylar Approach

The sitting, lateral park-bench, or prone position may be used. In the prone position, the head should be turned to the side of the lesion (at least 20 degrees), and a rigid three-pin head holder should be used. The sitting position provides an excellent exposure, but it carries the risk of air embolism.

A straight dorsolateral incision may be used, although an inverted J-shaped incision is preferred (Fig. 169-9). This incision begins at the mastoid process, extends rostrally and medially, and then extends caudally in the midline to the level of C6. Because the occipital muscles cover the craniectomy after the use of an inverted J-shaped incision (compared with a linear incision placed over a craniectomy), this incision is useful in preventing postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage.

Salas et al.4 have defined four varieties of dorsolateral craniocervical approaches. The transfacetal approach is used to treat extradural and intradural lesions ventral to the upper cervical spinal cord. The retrocondylar approach is performed for intradural lesions that are located predominantly lateral or ventrolateral to the spinomedullary region or to expose the extradural portion of the vertebral artery. The partial transcondylar approach is performed to treat lesions that are located predominantly ventral to the spinomedullary junction. The complete transcondylar approach is performed to treat extradural lesions. The extreme lateral transjugular approach is performed to supplement the traditional lateral transtemporal approach for the treatment of jugular foramen lesions.

Ventral Approaches to the Upper Cervical Spine

Transoral Approach

Because the predominant difficulty with the transoral approach is the depth and narrowness of the operative field, a self-retaining retractor is imperative. Retraction of the uvula is also frequently necessary (see Fig. 169-3).

After dissection of the ventral surfaces of the atlas and axis laterally, a second self-retaining retractor is held to open the dorsal pharyngeal wall along the long axis of the spine. Stay sutures may be used to provide lateral retraction (see Fig. 169-1).

Median Labiomandibular Glossotomy

Median labiomandibular glossotomy provides a wide ventral exposure from the clivus to the lower cervical spine.5–7 A midline vertical incision starts from the lower lip, extends caudally, turns around the chin prominence, and again passes medially in the neck (Fig. 169-10). The mandible is cut in a stepwise configuration for subsequent approximation. The tongue is incised longitudinally from the central raphe, and the oropharyngeal mucosa is incised laterally.

When the mandible, mucosa, and tongue are divided, all the medial structures may be retracted laterally, and the dorsal structures, such as the epiglottis and the dorsal pharynx, are visualized.

Because of high morbidity rates, this technique is preferred mostly in cases with primary malignant or aggressive benign tumors.8

Bilateral Sagittal Split Mandibular Osteotomies

This approach is performed in orthognathic surgery to repair a variety of facial and jaw deformities. Because all the incisions that are made in this approach are intraoral, they are not associated with the cosmetic deformities.9 It is an adjunct to the transoral approach, and the retraction plane is rostrocaudal instead of lateral. Lingual or inferior alveolar nerve injuries are common complications.

Transthyroid Approach

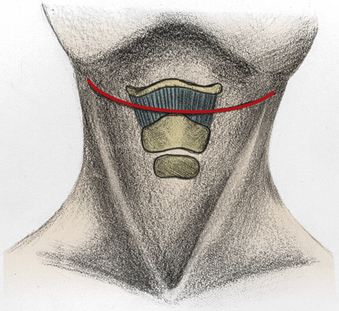

The transthyroid approach may provide access to the first four cervical vertebrae.10 A transverse incision is carried along the upper neck crease, between the hyoid bone and the thyroid cartilage, and is extended laterally (Fig. 169-11). The platysma and sternohyoid muscles are divided, and the thyrohyoid membrane is detached from the hyoid bone while the epiglottis is protected.

The internal laryngeal nerves are protected, and the ventral pharynx is entered. Rostral retraction of the hyoid bone and caudal retraction of the thyroid cartilage are performed. After incision of the dorsal pharyngeal wall, a self-retaining retractor exposes the vertebral bodies from C1 to C4. Because of the potential for significant morbidity, this approach is used infrequently. It has been associated with damage to the superior and internal laryngeal nerves and involves a significant risk of damaging the epiglottis.10

Ventrolateral Retropharyngeal Approach

The ventral retropharyngeal approach provides access to structures from the clivus to the third cervical vertebrae without entering the oral cavity.3,11–14 The advantages of this approach are lowered risks of infection and more extensive exposure of the upper cervical spine.

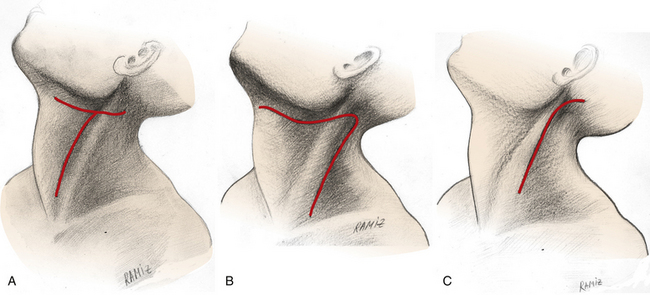

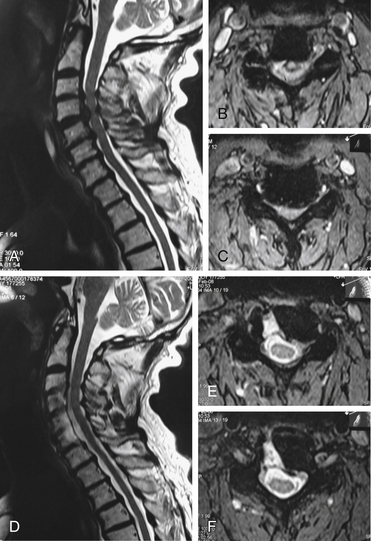

The upper transverse portion of a T-shaped incision is made just under the mandible. The vertical portion of the incision meets the sternocleidomastoid muscle caudally (Fig. 169-12A). Another option is a V-shaped incision (Fig. 169-12B).13

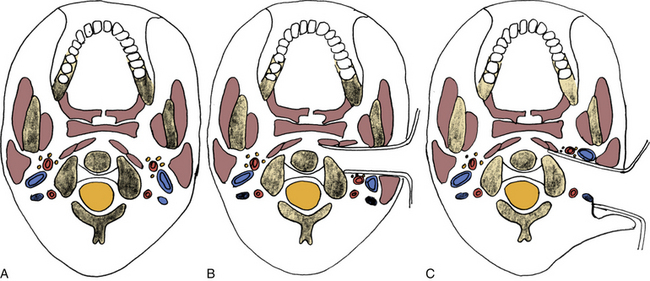

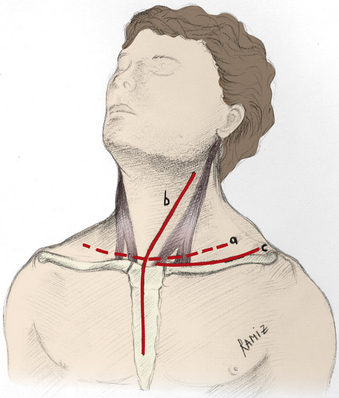

This ventral retropharyngeal approach may be called retrovascular or prevascular surgery (Fig. 169-13).15 Prevascular surgery involves an access medial to the carotid sheath and traverses the same fascial planes as in the ventrolateral lower cervical spine surgery12 (see Fig. 169-13B). It allows adequate spinal cord decompression up to the clivus and reconstruction of the anterior column of the spine with strut grafts and internal fixation.

After the platysma muscle is incised, the inferior division of the facial nerve and submandibular gland may be divided. The carotid sheath is identified and protected. The dorsal belly of the digastric muscle is traced and transected near its tendon. To retract the larynx, the stylohyoid muscle is transected. The hypoglossal nerve is identified and protected. The retropharyngeal space is opened and bluntly dissected. After retraction of the longus colli muscles, a self-retaining retractor is positioned.1,13 It may be difficult to place a self-retaining retractor in this opening. A table-mounted system may be useful in this region.

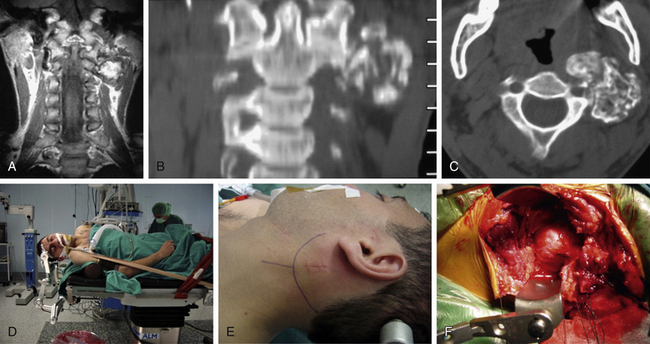

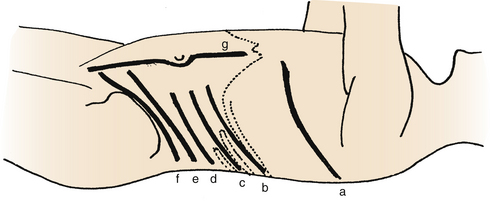

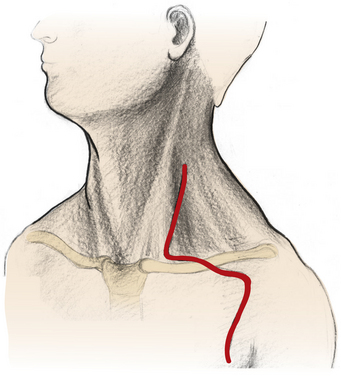

Lateral Cervical Approach

Some authors refer to the lateral cervical approach as a retrovascular variant of the ventral retropharyngeal approach.12 It is an anatomically complex access that requires sternocleidomastoid muscle eversion; exposition of the spinal accessory nerve and medial mobilization of the jugular vein, vagus nerve, carotid artery, vertebral artery, and cranial nerves XII, IX, VII16 (Fig. 169-14). Although it provides a true lateral access to the upper cervical spine, only limited access is obtained, and neither grafting nor extensive bony decompression can be achieved. It is also noted to have a significant association with vertebral artery damage.17

The major difference between a ventrolateral retropharyngeal approach and a straight ventral retropharyngeal approach is that the exposure is lateral to the carotid sheath.14,17,18

A hockey-stick incision is fashioned along the ventral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The incision begins behind the ear, proceeds caudally over the mastoid process, and extends below the mandibular angle toward the midline (Fig. 169-12C).

The external jugular vein is ligated and divided. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is divided transversely below the mastoid process. The occipital artery is also ligated. The greater auricular and accessory nerves are identified and protected. A dissection plane is developed dorsal to the carotid sheath and the retropharyngeal space.16

This approach may be fashioned for primary tumors of the upper cervical spine (Fig. 169-15).

Dorsal Approaches to the Subaxial Cervical Spine

Laminoforaminotomy for Cervical Disc Disease

In laminoforaminotomy for cervical disc disease, three different positions may be used: the prone position, the sitting position, and the lateral or park-bench position.19 Because lateral muscle retraction is necessary for exposure, hyperflexion and hyperextension should be avoided. If the spine is hyperflexed, the tightened muscles and tendons make lateral retraction difficult. If the spine is hyperextended, the interlaminar spaces close, and interlaminar exposure is difficult.19

A midline dorsal or paramedian dorsal incision may be used. The dorsal paramedian incision is used only for single-level laminoforaminotomy.19 This is a muscle-splitting approach, with only dissection of the muscles from the lamina and facet surfaces. This approach may be used for the keyhole foraminotomy.20

The classical midline dorsal approach requires the resection of the muscle attachments from the spinous processes to expose the facets and laminae.21 Only strong lateral retraction is needed to retract the muscles.

Ventral Approaches to the Subaxial Cervical Spine

Ventromedial Approach

Exposure of the disc space and vertebral body is usually accomplished by a ventromedial approach.22–25 The patient is positioned supine with the head and neck neutral or slightly extended. Extension of the upper cervical region, with chin retraction, is helpful to reach the C2-3 level. Extension of the midlower cervical region is helpful to reach the high thoracic region. The head is turned away from the surgeon. In the setting of severe cervical stenosis, extreme extension of the cervical spine may cause spinal cord damage and therefore should be avoided.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle is the surface incision landmark for the ventral approach. Either a transverse or a longitudinal incision is appropriate (see Fig. 169-14). Rengachary26 suggests a longitudinal incision for patients with a short neck and kyphotic deformity. The incision begins below the angle of the mandible, extends forward toward the hyoid bone, extends caudally over the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and terminates in the suprasternal notch (see Fig. 169-14).26

The carotid sheath is easily identified under the muscle. Both may be retracted laterally by the surgeon’s fingers (Fig. 169-16A). Rostrally, the 12th cranial nerve and, caudally, the recurrent laryngeal nerve should be avoided. Other structures that cross the wound transversely may be sacrificed if necessary. These include the inferior and superior thyroid veins and arteries, the facial veins, and the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle. Injury to the superior laryngeal and superior thyroid artery should be avoided.

The three main retraction systems that are available for ventral cervical surgery are hand-held retractors, self-retaining retractors, and table-fixed retractors (see Fig. 169-4). Saunders16 prefers a table-fixed retraction system for both the ventromedial and ventrolateral approaches. Retractors themselves may cause injury to the lateral structures, such as the carotid artery, internal jugular vein, cranial nerves 10 and 12, nerve roots, sympathetic chain, thoracic duct, and lung apex. The medial structures, such as the esophagus and the trachea, are also at risk. Manual retraction is usually used at the beginning of the dissection until the deep cervical fascia is opened and the longus colli muscles are visualized.

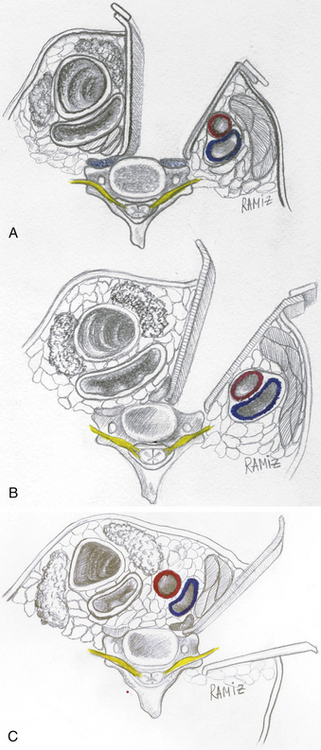

Ventrolateral Approach

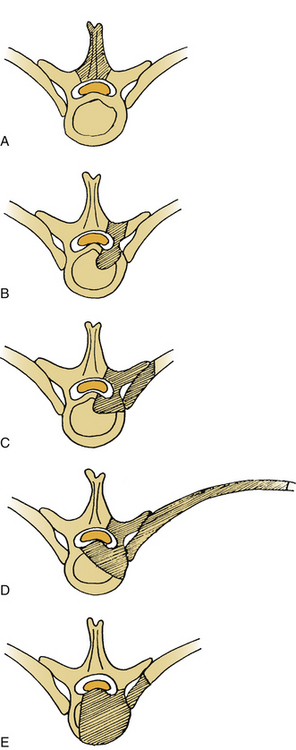

The lateral approach to the cervical spine from C3 to C7 can be performed via a ventrolateral exposure. However, the lateral exposure of C1 and C2 can only be performed with the dorsolateral transcondylar approach.27

The ventrolateral approach has two variations. The trajectory of one approach is medial to the carotid artery, whereas the trajectory of the other is lateral (Figs. 169-16B and C). In the latter approach, the sternocleidomastoid muscle is retracted medially with the carotid sheath. Therefore, retraction of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is avoided.

With either variation, the lateral retractor blade is positioned just lateral to the tubercle of the transverse process, and the medial retractor blade is positioned just medial to the uncinate process (see Figs. 169-16B and C). This exposes the ipsilateral longus colli muscle, which, together with the sympathetic chain, is mobilized medially. The muscle insertions to the transverse process are divided. Positioning and incision are the same in the ventrolateral approach as in the ventromedial approach.

A ventrolateral approach medial to the carotid sheath is most frequently used to expose the vertebral artery and the nerve root foramen.28,29 It is essentially a medial approach without midline exposure.29,30 The carotid sheath is retracted laterally as with the ventromedial approach.

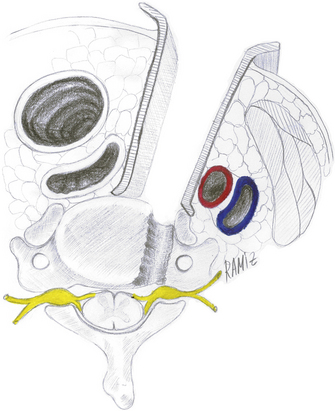

Decompression of lateral cervical disc herniations may be done via the same route. This approach may be termed the ventral cervical foraininotomy,31 ventrolateral transpedicular foraminotomy,1 or microsurgical ventral cervical foraminotomy-uncinatectomy.32 The colli muscles are mobilized, allowing dissection around the lateral aspect of the vertebral body; a retractor between the vertebral body and the vertebral artery is placed; and the lateral portion of the uncovertebral joint is drilled. The herniated disc and uncovertebral osteophytes are removed to decompress the exiting nerve root (Fig. 169-17).

A ventrolateral approach lateral to the carotid sheath and sternocleidomastoid muscle is also termed the oblique cervical approach33 With this exposure, the incision may be fashioned lateral to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Positioning is similar to that in the ventromedial approach. The head and neck may be slightly turned to the contralateral side. Both the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the great vessels are retracted medially, together with the trachea and the esophagus. A self-retaining retractor may be used, with care taken that the lateral blades do not cause severe retraction of the nerve roots.33,34

Oblique corpectomy is an effective alternative to other ventral cervical decompressions with advantages of no need for a graft or plate (Fig. 169-18).33,35

Dorsal and Ventral Approaches to the Cervicothoracic Junction

The dorsal approaches are similar to those used for lower cervical dorsal approaches.

Lower Ventromedial Cervical Approach

The lower ventromedial cervical approach is indistinguishable from that used in the midcervical to lower cervical spine.36

Transsternal Approach

The transsternal approach provides a direct ventral route through a median sternotomy.37 The morbidity and mortality are high. Hodgson and Yau38 have reported a 40% mortality rate. Furthermore, this approach provides little advantage over the transmanubrial approach because the soft tissue structures are the predominant limiting factors.

Transmanubrial Approach

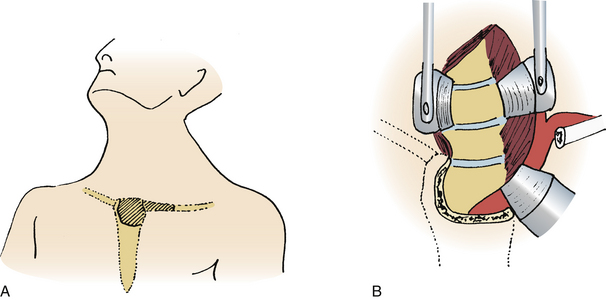

The transmanubrial approach is a variation of the transsternal approach.39 It is performed by using an osteotomy of the manubrium, with or without a medial claviculotomy.38–42 Sundaresan et al.43 recommend resection of the medial third of the clavicle along with the creation of a window in the manubrium (Fig. 169-19).

FIGURE 169-19 A, Transmanubrial exposure. B, Resection of the manubrium and the medial part of the clavicle.

Either of two incisions may be used: a T-shaped incision, with the transverse arm 2 cm above the clavicle and the midline vertical arm extending to the sternum, or a medial sternocleidomastoid incision extending to the sternum.38,44 This incision permits a simultaneous ventromedial midcervical approach (Fig. 169-20).

The upper outer corner of the manubrium, the first costal cartilage, and the medial third of the clavicle are divided. With this exposure, the great vessels and the lower roots of the brachial plexus are retracted. If it is connected to a ventromedial cervical exposure, a generous exposure to the cervicothoracic vertebrae from C3 to T5 can be obtained.45

The sternocleidomastoid muscle and the omohyoid muscle are divided. The phrenic nerve, the 11th cranial nerve, the sympathetic chain, and, on the left side, the thoracic duct should be protected. If necessary, the left innominate vein may be divided.44

Transverse Supraclavicular Approach

The transverse supraclavicular approach was originally described as an exposure for upper thoracic sympathectomy.46 A transverse incision parallel to the clavicle and extending beyond the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is used.18,42,47 The sternocleidomastoid muscle, the omohyoid muscle, and the strap muscles are divided. The carotid sheath, the internal jugular vein, and the phrenic nerve are identified and protected. Medial retraction of the neurovascular structures provides a limited exposure lateral to the C7 vertebral body.

Transclavicular Approach

The transclavicular approach (splitting the clavicle) provides an adequate access to the cervicothoracic junction. This approach is most useful for cervicothoracic spine tumors with paravertebral-plexus involvement. Dividing the clavicle assists in the separation of the intrathoracic components from the lung. A zigzag-shaped incision over the clavicle may be used48 (Fig. 169-21).

FIGURE 169-21 A zigzag-shaped incision for transclavicular approach to cervicothoracic spine tumors with paravertebral-plexus involvement.

(Redrawn from Kuho T, Nakamura H, Yamano Y: Transclavicular approach for a large dumbbell tumor in the cervicothoracic junction. J Spinal Disord 14:79–83, 2001.)

Transaxillary Extrapleural Approach

The transaxillary extrapleural approach is a high thoracic variant of the transthoracic approach. Its advantage lies in the preservation of the pectoral and shoulder girdle muscles.20 Its disadvantage is that it places the brachial plexus at risk for retraction and stretch injury.

A transverse incision is made from the border of the pectoralis muscle to the border of the latissimus dorsi muscle. The third rib is resected, and the dissection is carried through the third rib bed.39,47,49,50 Retraction is essentially an extrapleural approach. With blunt dissection, the apex of the lung is retracted caudally. A self-retaining retractor may be used.

Lateral Parascapular Extrapleural Approach

With this approach, the parascapular shoulder muscles are reflected off the spinous processes to the scapula with preservation of neurovascular structure.51 The upper dorsal ribs are removed, the rami communicantes of C8 and T1 are transected, and the sympathetic chain is displaced ventrolaterally. This approach provides easy access to the T2-4 vertebrae.51

Transpleural Transthoracic Approach

With the transpleural transthoracic approach, the upper thoracic vertebrae can be adequately approached through the fourth rib.52 The left-side-up position is preferred, because it is easier to mobilize the aorta than the vena cava. In the event of vascular injury, it is also easier to repair the aorta than the vena cava. It may be preferred over the extrapleural method, because lung retraction is easier. Unlike the extrapleural approach, however, a tube thoracostomy is required.

Trapdoor Approach

With the trapdoor approach, a partial median sternotomy and a ventrolateral approach are added to a standard ventral approach to the cervical spine along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.53 The sternoclavicular joint and clavicle itself are preserved. It provides a bilateral ventral approach from C4 to T3. Although it provides a wide exposure and proximal control of important vessels, it has a very high morbidity rate (Fig. 169-22).

Dorsal Approaches to the Thoracic and Thoracolumbar Spine Junction

Thoracic Laminectomy

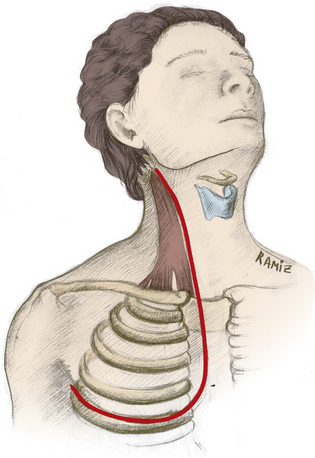

The patient is positioned prone on a chest frame or on laminectomy rolls that allow the abdominal contents to be free of pressure, thereby reducing venous compression and decreasing blood loss during surgery. Both the pelvis and the knees are flexed to enhance the normal thoracic kyphosis (Fig. 169-23). Specialty tables and frames may be used to minimize abdominal pressure. These tables may also facilitate intraoperative radiography.

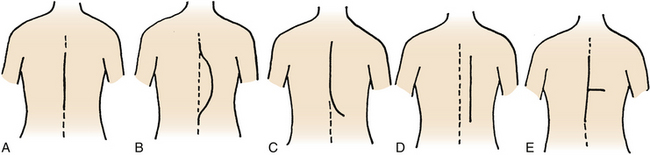

A few surgeons advocate the lateral position for thoracic laminectomy. This may be particularly useful in the obese patient. A dorsal midline incision is used (Fig. 169-24A).

Transpedicular Approach

The transpedicular approach may be used for thoracic disc removal and vertebral body biopsy.54 It may also be performed in the cervicothoracic junction. The prone position is used with the transpedicular approach.

A midline vertical incision is performed (see Fig. 169-24A). The paraspinous muscles and the soft tissues are retracted to one side. The facet joint and the pedicle are removed by using a high-speed bur. The dorsal aspect of the vertebral body adjacent to the portion of the vertebral body near the rostral intervertebral disc space may be reached through the pedicle.

Costotransversectomy

This approach allows exposure of dorsal and dorsolateral structures, without violating the pleural cavity. It is different from the lateral extracavitary approach, because it involves a midline exposure and a plane of dissection that is medial to the erector spinae muscles. It was first described for drainage of tuberculous abscesses.55

The patient is placed in the prone position and a midline vertical incision is made (see Fig. 169-24A). A modified T-shaped incision has also been described56 (Fig. 169-24E). After standard bilateral subperiosteal dissection, a plane of dissection on the ipsilateral side is extended to the tips of the transverse processes and proximal ribs. The 3- to 4-cm medial aspect of one or two ribs is then cut, disarticulated from its costotransverse and costovertebral articulations, and resected.

To find the ipsilateral pedicle, the neurovascular bundle is identified under the rib bed and followed proximally to the neural foramen. After the transverse process and the pedicle have been removed, the lateral aspect of the thecal sac is visualized. Self-retaining retractors are used.

There is a controversy over the necessity of performing a rhizotomy of the associated nerve root during the procedure. Since the patients whose nerve roots were preserved can show late neuropathic pain, routine transection of the associated nerve root proximal to the ganglion may be desirable.3

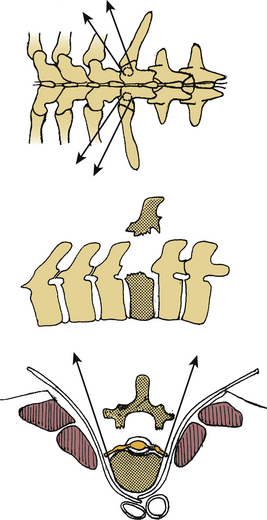

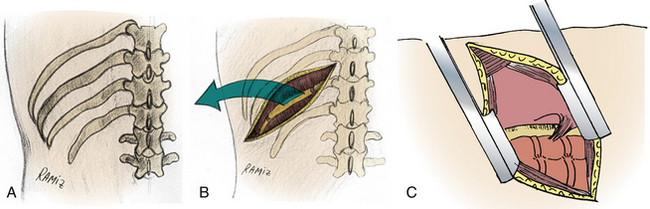

Lateral Extracavitary Approach

The lateral extracavitary approach is a modification of costotransversectomy. It was introduced and popularized by Larson et al.57 and then adopted by other surgeons.47,58,59 The prone position is used frequently, although a three-quarter prone position has also been described (Fig. 169-25).58 Several variations of a parasagittal incision are described (see Fig. 169-24).23 Larson et al.57 use a midline hockey-stick incision. This approach provides simultaneous access to both the dorsal and ventral aspects of the spine. Dorsal instrumentation may be placed via the same incision that is used for decompression.

Dissection is carried to the lateral border of the paraspinous muscles. The paraspinous muscles are mobilized in a lateral-to-medial direction. They may also be transected in a transverse fashion as was originally described by Capener.60 The lateral exposure reaches 8 to 10 cm lateral to the midline. The remaining portion of the operation is similar to the costotransversectomy. It differs from the costotransversectomy, however, because an approximately 15% to 30% ventral angle of exposure is gained by the lateral extracavitary approach (Fig. 169-26).

Dorsal En Bloc Total Spondylectomy

En bloc total spondylectomy may be performed by bisecting the affected vertebrae through the pedicles and removing the vertebra en bloc.27 This method was first introduced by Tomita et al.61,62 and then used in other centers.63,64 There are two variations described in the following paragraphs.27

Single Dorsal Approach: For Lesions from T1 to L2

Tomita et al.27,61,62 proposed the removal of the dorsal component and lateral components of the spine en bloc by pediculotomy using a fine threadwire saw. If the unilateral pedicle is affected by the tumor, osteotomy may be performed through a neighboring healthy lamina. The involved nerve root occasionally had to be ligated and cut. If the affected pedicle or vertebral body markedly compressed the nerve root, the more severely affected side is sacrificed. Sacrificing both nerve roots in less important areas such as the thoracic spine is possible. After the dorsal bony column has been removed, the epidural venous bleeding is controlled (Fig. 169-27).

Combined En Bloc Total Spondylectomy: For Lesions from L3 to L5

The first step is a dorsal approach. The dorsal procedure is similar to the method of Tomita et al.61,62 After removal of the dorsal bony column, the psoas muscles with segmental vessels are dissected as ventrally as possible on the contralateral side of the ventral approach. The posterior longitudinal ligamentum and the dorsal and contralateral part of the adjacent intervertebral disks are cut through the dorsal approach. After dorsal stabilization according to the principle of “one above, one below” using a pedicle screw system, a ventral procedure, including en bloc corpectomy and reconstruction of the ventral column, is performed by replacing the affected vertebral body using a vertebral prosthesis or a titanium cage. This is supported by ventral spinal instrumentation. Bone is also placed around the prosthesis or inside the cages. The ventral fixation construct includes one vertebra above and one below the affected vertebra.

Ventral Approaches to the Thoracic and Thoracolumbar Spine Junction

Transpleural Thoracotomy

When a ventrolateral exposure of the spine is required for pathologic processes located rostral to the T12 vertebral body, a transthoracic approach is often appropriate.23,36,65 It is most useful for the midthoracic segments between T3 and T11.

The main advantage of a thoracotomy is direct access to ventral pathology, multilevel exposure, and ease of ventral instrumentation. The disadvantages of this approach include violation of the thoracic cavity, the need for a tube thoracotomy, and a relatively weak instrumentation construct (short-segment fixation).

A curved incision is fashioned around the medial aspect of the scapula for a thoracotomy in the upper thoracic spine (T2-5) vertebral lesions (Fig. 169-28). For lesions between T5 and T10, a curvilinear incision is made along the designated rib, extending from the costochondral articulation ventrally to the lateral aspect of the paraspinous muscles dorsally (see Fig. 169-23A).

After the lung is collapsed, a self-retaining thoracotomy retractor is used. A malleable retractor with a reversed curve is placed on the ventral aspect of the vertebral body.66

Extrapleural Thoracotomy

An extrapleural thoracotomy approach provides a shorter route to the ventral thoracic spine. Its major advantage is avoidance of pleural cavity violation.67 Postoperative morbidity, particularly pain and pulmonary complications, are thus reduced.

Intercostal muscles are detached subperiosteally over an 8- to 10-cm rib segment.67 Then, in the resected rib segment, the endothoracic fascia is incised in line with the rib bed. The parietal pleura is widely dissected from the undersurface of the endothoracic fascia with blunt dissectors. After adequate dissection and freeing the parietal pleura over the vertebral body is ensured, a self-retaining crank-type retractor facilitates the exposure.

Retropleural approaches are recommended to avoid direct lung trauma and to minimize the need for a tube thoracostomy. In the midthoracic spine, only limited lesions such as thoracic disc herniations may be approached via a retropleural thoracotomy. It is easier to perform an extrapleural operation at the thoracolumbar junction. The 11th or 12th rib extrapleural-retroperitoneal approach is a prototype for this.68 The extrapleural space can be expanded to T10-L2. Some authors have advised resectimg the 12th rib to facilitate exposure.67

Transdiaphragmatic Approach

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position. For the thoracolumbar junction, the classical operation is the 9th or 10th rib transpleural-retroperitoneal thoracoabdominal approach. Most commonly, a T10 rib incision is made. The 10th rib may then be resected (Fig. 169-29). A self-retaining thoracotomy retractor is used as for thoracotomy. Care must be taken not to injure the spleen on the left side or the liver on the right side. The major disadvantage of this method is the division of the diaphragm and entering into two body cavities.

Kim et al.68 have recommended using an 11th rib extrapleural-retroperitoneal approach (Fig. 169-30). Since it prevents entering the pleural cavity, thoracic complications should be minimal. However, it is technically demanding, it prolongs the operative time, and the operative exposure is limited.

Ventrolateral Retroperitoneal Approach

A supine position is appropriate for low ventrolateral lumbar exposure, using a log roll to elevate the operative side. For thoracolumbar approaches, however, a right lateral decubitus position on an ordinary operating table is preferred. Table-mounted retractor systems may help to maintain this position during the operation.

The skin incision is run obliquely, caudally, and ventrally. This so-called flank incision can be made between the tip of the 12th rib and the anterior superior iliac spine. It begins dorsally at the edge of the paravertebral muscle and terminates at the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis muscle. However, the incision may vary on the basis of the spinal level and the surgical indication (see Fig. 169-29).23

For an infradiaphragmatic retroperitoneal exposure, subperiosteal dissection of the crus of the diaphragm from its vertebral attachments aids in the visualization of the higher lumbar and lower thoracic vertebral bodies. Resection of the 11th or 12th rib may be used to gain access to the thoracolumbar and upper lumbar spine via this approach.69–71

The vascular supply of the spinal cord is worthy of consideration. The most common location of the entrance of the radiculomedullary artery of Adamkiewicz into the spinal canal is on the left, in the midthoracic to lower thoracic region. Generally, the ventrolateral approach is not affected by the location of radiculomedullary arteries, because the angle of the approach does not violate terminal-end arteries. If the surgeon intends to disrupt the soft tissues at the level of the neuroforamina, terminal spinal cord blood flow may be endangered. In this circumstance, an alternative approach should be considered.

Dorsal Approaches to the Lumbar and Lumbosacral Spine

Paraspinal Approach

The paraspinal approach is used for far-lateral disc herniation72 or for dorsolateral fusion of the transverse processes.73 Its main advantage is the decrease in paraspinous muscle retraction.

The patient is placed in the prone position. Wiltse et al.73 have described bilateral paramedian incisions and a muscle-splitting dissection between the erector spinae and multifidus muscles. If the operation is performed for an extraforaminal disc protrusion, a unilateral small incision is usually sufficient.

Jane et al.72 have described a modification of this approach that makes it possible to expose the root both from medial and lateral to the facet joint. With this approach, the incision is extended from the midline, but the muscle fascia is incised as an arc, and the spaces first medial to the paraspinous muscles and then lateral to these are exposed.72

Lateral Extracavitary Approach

The lateral extracavitary approach in the lumbar spine is similar to the lateral extracavitary approach in the thoracic spine. However, it is more important to preserve the lumbar nerve roots. Because there is no rib in the lumbar region and because the nerve roots pass through the bulky iliopsoas muscle, the lateral extracavitary approach is technically demanding in the lumbosacral region. The obstacle of the iliac crest is another limitation of this approach.5,49,50,57

Ventral Approaches to the Lumbar and Lumbosacral Spine

Ventrolateral Transpsoatic Approach

Although this technique was used to implant prosthetic disc nucleus devices in patients with symptomatic degenerative disc disease,74 it was then called an extreme lateral interbody fusion, and for the risks of iatrogenic injury to the lumbosacral plexus, electrophysiologic monitoring of the retracted roots inside the psoas muscle is recommended.75

Pelvic Brim Extraperitoneal Approach

For a minimally invasive exposure of the L4-5 level, a 5- to 8-cm horizontal incision through the anterior rectus sheath has been described. The rectus abdominis muscle is then retracted medially. After incision of the posterior rectus sheath, the retroperitoneum is exposed.23,58,70

Transperitoneal Approach

It is possible to reach all the midlumbar and lower lumbar segments and the sacrum via the transperitoneal approach.66,76,77 The transperitoneal approach provides a direct ventral exposure of the lumbar and sacral spine. It is most useful for L5-S1 pathology, when a wide exposure of this region is required.78 The requirement of a laparotomy and the potential for neural and vascular injury are its disadvantages.

Dorsal Approaches to the Sacrum

In case of a sacrectomy, it is suggested that the patient be prepared the day before surgery with repeated enemas. At the beginning of the operation, a vaginal pad is inserted into the rectum.

The patient is placed in the prone position. It is important to keep the abdomen free of pressure so that bleeding is minimized. If a lumbosacral fusion is to be undertaken and supplemented with internal fixation, the lumbosacral junction should be placed in extension. This can easily be achieved by placing pillows or bolsters under the hips. In the Krause position, the sacrum is prominent and constitutes the highest point of the table (Fig. 169-31).79

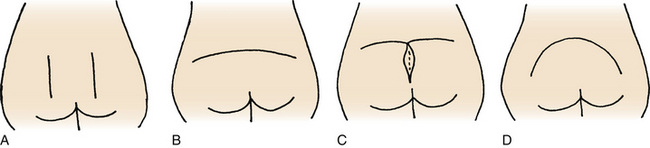

The incision varies according to the pathology and planned operation. A midline vertical incision, transverse incision, upward arched incision, or downward arched incision may be used (Fig. 169-32).

Another problem during the sacrum tumor surgery is the necessity for inclusion of the biopsy scar into the excision material. In this case, a T-shaped incision may be most suitable (see Fig. 169-32C).

Wiltse et al.73 introduced an incision and retraction technique using one or two incisions 5 cm lateral to the midline and medial to the posterior superior iliac spine (see Fig. 169-32A). The dissection is deepened to the sacrospinalis muscle and the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra. Wiltse et al. have used this approach for lumbosacral fusions. Bone grafts from the dorsal iliac crest can easily be obtained with the same exposure.

Ventral Approaches to the Sacrum

Retroperitoneal Approach

A supine position with the legs elevated and partly separated (lithotomy position) is advised.80 If a unilateral dissection is planned, one side of the pelvis may be elevated.

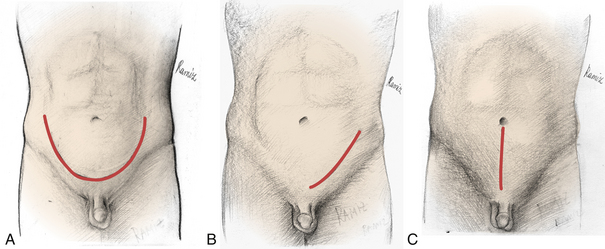

For bilateral retroperitoneal exposure, a large semicircular incision is performed through the skin on the lower abdomen (Fig. 169-33A). The rectus abdominis tendon is severed bilaterally just above the pubic bone. For unilateral exposure, a flank incision without violating the rectus abdominis muscle is satisfactory (Fig. 169-33B).

Transperitoneal Approach

The patient is placed in the supine position, and an inferior midline abdominal incision is made (Fig. 169-33C). The median raphe of the rectus abdominis muscle is divided. A suprapubic transverse incision is not recommended, for it requires a rectus abdominis muscle section.

Combined Abdominosacral Approach

Total resection of the major primary sacral tumors (i.e., chordoma, chondrosarcoma, giant cell tumor) requires a combined approach, both ventral and dorsal.39,81 If the rectum can be preserved, the operation is begun ventrally and finished dorsally. If not, a ventral, dorsal, and ventral approach sequence is advocated.80

Some surgeons prefer a dorsal exposure in the prone position. The patient is then placed in the lateral decubitus position so that a separation of tissue planes from both sides is possible.43,82 In this case, two surgeons, one from the dorsal and the other from the ventral side, may operate simultaneously.

Abe E., Kobayashi T., Murai H., et al. Total spondylectomy for primary malignant, aggressive benign, and solitary metastatic bone tumors of the thoracolumbar spine. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:237-246.

Benzel E.C. Surgical exposure of the spine: an extensile approach. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1995.

Charles R., Govender S. Anterior approach to the upper thoracic vertebrae. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1989;71:81-84.

Hall J.E., Denis F., Murray J. Exposure of the upper cervical spine for spinal decompression by a mandible and tongue splitting approach. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1977;59:121-123.

Hodgson A.R., Yau A.C.M.C. Anterior surgical approaches to the spinal column. In: Apley A.G., editor. Recent advances in orthopaedics. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1969:289-323.

Woodard E.J. Indications, complications, and comparison of approaches. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Surgical exposure of the spine: an extensile approach. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1995:157-178.

1. Grundy P.L., Germon T.J., Gill S.S. Transpedicular approaches to cervical uncovertebral osteophytes causing radiculopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(1S):21-27.

2. Tresserras P. New retractor for a surgical approach to the spine: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:161-162.

3. Menezes A.H. Surgical approaches to the craniocervical junction. In: Frymoyer J.W., editor. The adult spine: principles and practice. New York: Raven; 1991:967-985.

4. Salas E., Sekhar L.N., Ziyal I.M., et al. Variations of the extreme-lateral craniocervical approach: anatomical study and clinical analysis of 69 patients. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(4S):206-219.

5. Arbit E., Petterson R.H.Jr. Combined transoral and median labiomandibular glossotomy approach to the upper cervical spine. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:672-674.

6. Hall J.E., Denis F., Murray J. Exposure of the upper cervical spine for spinal decompression by a mandible and tongue splitting approach. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1977;59:121-123.

7. Moore L.J., Schwartz H.C. Median labiomandibular glossotomy for access to the cervical spine. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:909-912.

8. Honma G., Murota K., Shiba R., Kondo H. Mandible and tongue-splitting approach for giant cell tumor of axis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14:1204-1210.

9. Vishteh A.G., Beals S.P., Joganic E.F., et al. Bilateral sagittal split mandibular osteotomies as an adjunct to the transoral approach to the anterior craniovertebral junction. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:267-270.

10. Fang H.S.Y., Ong G.B. Direct anterior approach to the upper cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1962;49:1588-1604.

11. DeAndrade J.R., MacNab I. Anterior occipito-cervical fusion using an extra-pharyngeal exposure. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1969;51:1621-1626.

12. McAfee P.C., Bohlman H.H., Riley L.H., et al. The anterior retropharyngeal approach to the upper part of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1987;69:1371-1383.

13. Riley L.H. Surgical approaches to the anterior structures of the cervical spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;91:16-20.

14. Whitecloud T.S., Kelley L.A. Anterior and posterior surgical approaches to the cervical spine. In: Frymoyer J.W., editor. The adult spine: principles and practice. New York: Raven; 1991:987-1013.

15. Laus M., Pignatti G., Malaguti M.C., et al. Anterior extraoral surgery to the upper cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:1687-1693.

16. Saunders R.L. Anterior reconstructive procedures in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Clin Neurosurg. 1991;37:682-721.

17. Whitesides T.E.Jr, Kelly R.P. Lateral approaches to the upper cervical spine for anterior fusion. South Med J. 1966;50:879-883.

18. Johnson R.M., Murphy M.J., Southwick W.O. Surgical approaches to the spine. In Rothman R.H., Simeone F.A., editors: The spine, ed 3, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1992.

19. Ducker T.B., Zeidman S.M. Cervical disk diseases. Part II: Operative procedures. Neurosurg Q. 1992;2:144-163.

20. Scoville W.B., Dohrmann G.J., Corhill G. Late results of cervical disc surgery. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:203-210.

21. Spurling R.G., Bradford F.K. Neurologic aspects of herniated nucleus pulposus. JAMA. 1939;113:2019-2022.

22. Batzdorf U., Batzdorff A. Analysis of cervical spine curvature in patients with cervical spondylosis. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:827-836.

23. Benzel E.C. Surgical exposure of the spine: an extensile approach. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1995.

24. Cloward R.B. New method of diagnosis and treatment of cervical disc disease. Clin Neurosurg. 1962;8:93-103.

25. Saunders R.L. On the pathogenesis of the radiculopathy complicating multilevel corpectomy. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:408-413.

26. Rengachary S.S. Partial median corpectomy with fibular grafting for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurgical operative atlas. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons. 1992:11-24. vol. 2, no 6

27. Abe E., Kobayashi T., Murai H., et al. Total spondylectomy for primary malignant, aggressive benign, and solitary metastatic bone tumors of the thoracolumbar spine. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:237-246.

28. Louis E., Ruge D. Lateral approach to the cervical spine. In: Wiltse L.L., Ruge D., editors. Spinal disorders. London: Henry Kimpton; 1977:132-136.

29. Verbiest H. Anterolateral operations for fractures and dislocations in the middle and lower parts of the cervical spine: report of a series of forty-seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1969;51:1489-1530.

30. Manabe S., Tateishi A., Ohno T. Anterolateral uncoforaminotomy for cervical spondylotic myeloradiculopathy. Acta Orthop Scand. 1988;59:669-674.

31. Johnson J.P., Filler A.G., McBride D.Q., Batzdorf U. Anterior cervical foraminotomy for unilateral radicular disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:905-909.

32. Tascioglu A.O., Attar A., Tascioglu B. Microsurgical anterior cervical foraminotomy (uncinatectomy) for cervical disc herniation: report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:121-125.

33. George B., Zerah M., Lot G., et al. Oblique transcorporeal approach to anteriorly located lesions in the cervical spinal cord: Technical note. Acta Neurochir. 1993;121:187-190.

34. Anson J.A. Lateral exposures of the cervical spine and vertebral artery. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Surgical exposure of the spine: an extensile approach. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1995:69-81.

35. Koc R.K., Menku A., Akdemir H., et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy and radiculopathy treated by oblique corpectomies without fusion. Neurosurg Rev. 2004;27:252-258.

36. Perry J. Surgical approaches to the spine. In: Pierce D.S., Nickel V.H., editors. The total care of spinal cord injuries. Boston: Little, Brown; 1977:53-57.

37. Cauchoix J., Binet J.P. Anterior surgical approaches to the spine. Ann R Coll Surg. 1957;21:237-239.

38 Hodgson A.R., Yau A.C.M.C. Anterior surgical approaches to the spinal column. In: Apley A.G., editor. Recent advances in orthopaedics. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1969:289-323.

39. Sundaresan N., DiGiancinto G.V. Surgical considerations and approaches. In: Sundaresan N., Schmidek H.H., Schiller A.L., et al, editors. Tumors of the spine: diagnosis and clinical management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:358-379.

40. Birch R., Bonney G., Marshall R.W. A surgical approach to the cervicothoracic spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1990;72:904-907.

41. Charles R., Govender S. Anterior approach to the upper thoracic vertebrae. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1989;71:81-84.

42. Sundaresan N., Shah J., Feghali J.G. A transsternal approach to the upper thoracic vertebrae. Am J Surg. 1984;148(4):473-477.

43. Sundaresan N., Galicich J.H., Chu F.C., Huvos A.G. Spinal chordomas. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:312-319.

44. Darling G.E., McBroom R., Perrin R. Modified anterior approach to the cervicothoracic junction. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:1519-1521.

45. Pointillart V., Aurouer N., Gangnet N., Vital J.M. Anterior approach to the cervicothoracic junction without sternotomy: a report of 37 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2875-2879.

46. Nanson E.M. The anterior approach to upper dorsal sympathectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1957;104:118-120.

47. Watkins R.G. Surgical approaches to the spine. New York: Springer Verlag; 1983.

48. Kubo T., Nakamura H., Yamano Y. Transclavicular approach for a large dumbbell tumor in the cervicothoracic junction. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:79-83.

49. Breslau R.C. Transaxillary approach to the upper dorsal spine. In: Watkins R.D., editor. Surgical approaches to the spine. New York: Springer Verlag; 1983:58-63.

50. Woodard E.J. Indications, complications, and comparison of approaches. In: Benzel E.C., editor. Surgical exposure of the spine: an extensile approach. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1995:157-178.

51. Fessler R.G., Dietze D.D., Millan M.M., Peace D. Lateral parascapular extrapleural approach to the upper thoracic spine. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:349-355.

52. Turner P.L., Webb J.K. A surgical approach to the upper thoracic spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1987;69:542-544.

53. Nazzaro J.M., Arbit E., Burt M. Trap door exposure of the cervicothoracic junction: technical note. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:338-341.

54. Patterson R.H.Jr, Arbit E. A surgical approach through the pedicle to protruded thoracic discs. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:768-772.

55. Menard V. Causes de la paraplegic dans le mal de Pott. Rev Orthop. 1894;5:47-64.

56. Garrido E. Modified costotransversectomy: a surgical approach to ventrally placed lesions in the thoracic spinal canal. Surg Neurol. 1980;13:109-113.

57. Larson S.J., Holst R.A., Hemmy D.C., et al. Lateral extracavitary approach to traumatic lesions of the thoracic and lumbar spine. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:628-637.

58. Benzel E.C. The lateral extracavitary approach to the spine using the three-quarter prone position. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:837-841.

59. Maiman D.J., Larson S.J., Luck E., El-Ghatit A. Lateral extracavitary approach to the spine for thoracic disc herniation: report of 23 cases. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:178-182.

60. Capener N. The evolution of lateral rhachotomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1954;36:173-179.

61. Tomita K., Kawahara N., Baba H., et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy for solitary spinal metastases. Int Orthop. 1994;18:291-298.

62. Tomita K., Kawahara N., Baba H., et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy: a new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:324-333.

63. Boriani S., Chevalley F., Weinstein J.N., et al. Chordoma of the spine above the sacrum: treatment and outcome in 21 cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:1569-1577.

64. Stener B. Technique of complete spondylectomy in the thoracic and lumbar spine. In: Sundaresan N., Schmidek H.H., Schiller A.L., et al, editors. Tumors of the spine: diagnosis and clinical management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:432-437.

65. Perot P.L.Jr, Munro D.D. Transthoracic removal of midline thoracic disc protrusions causing spinal cord compression. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:452-458.

66. Roy-Camille R., Mazel C. Surgical exposures and procedures. Laurin C.A., Riley L.H.Jr, Roy-Camille R., editors. Atlas of orthopaedic surgery, vol. 1. General principles and spine, Paris: Masson, 1989.

67. McCormick P.C. Retropleural approach to the thoracic and thoracolumbar spine. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:908-914.

68. Kim M., Nolan P., Finkelstein J.A. Evaluation of 11th rib extrapleural-retroperitoneal approach to the thoracolumbar junction. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(1S):168-174.

69. Harmon P.H. Anterior extraperitoneal lumbar disc excision and vertebral bone fusion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1963;16:169-198.

70. Harmon P.H. A simplified surgical technique for anterior lumbar diskectomy and fusion: avoidance of complications: anatomy of the retroperitoneal veins. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1964;37:130-144.

71. Hodgson M.B., Wong S.K. A description of a technique and evaluation of results in anterior spinal fusion for deranged intervertebral disc and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1968;56:133-162.

72. Jane J.A., Haworth C.S., Broaddus W.C., et al. A neurosurgical approach to far-lateral disc herniation: Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1990;72(1):143-144.

73. Wiltse L.L., Bateman J.G., Hutchinson R.H., et al. The paraspinal sacrospinalis-splitting approach to the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1968;50:919-926.

74. Bertagnoli R., Vazquez R.J. The AnteroLateral transPsoatic Approach (ALPA): A new technique for implanting prosthetic disc-nucleus devices. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16(4):398-404.

75. Ozgur B.M., Aryan H.E., Pimenta L., Taylor W.R. Extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF): a novel surgical technique for anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2006;6:435-443.

76. Freebody D., Bendall R., Taylor R.D. Anterior transperitoneal lumbar fusion. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1971;53:617-627.

77. Lane J., Moore E.S. Transperitoneal approach to the intervertebral disc in the lumbar area. Ann Surg. 1948;127:537-551.

78. Benzel E.C. Surgical exposure of the lumbosacral plexus and proximal sciatic nerve. In: Benzel EC, editor. Practical approaches to peripheral nerve surgery. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1992:153-159.

79. Gennari L., Azzarelli A., Quagliuolo V. A posterior approach for the excision of sacral chordoma. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1987;69:565-568.

80. Stener B., Gunterberg B. High amputation of the sacrum for extirpation of tumors. Principles and technique. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1978;3(4):351-366.

81. Localio S.A., Eng K., Ranson J.H.C. Abdominosacral approach for retrorectal tumors. Ann Surg. 1980;191:555-560.

82. Bridwell K.H. Management of tumors at the lumbosacral junction. In: Margulies J.Y., Floman Y., Faray J.P.C., et al, editors. Lumbosacral and spinopelvic fixation. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:109-122.