Chapter 336 Surgical Conditions of the Anus and Rectum

336.1 Anorectal Malformations

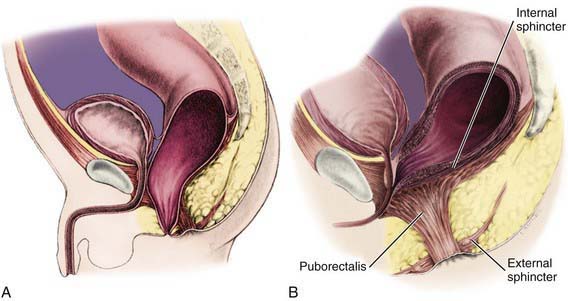

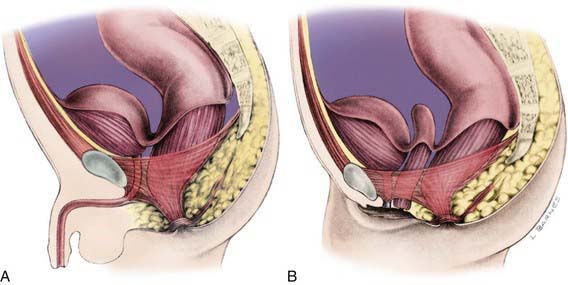

In understanding the spectrum of anorectal anomalies, it is necessary to consider the importance of the sphincter complex, a mass of muscle fibers surrounding the anorectum (Fig. 336-1). This complex is the combination of the puborectalis, levator ani, external and internal sphincters, and the superficial external sphincter muscles, all meeting at the rectum. Anorectal malformations are defined by the relationship of the rectum to this complex and include varying degrees of stenosis to complete atresia. The incidence is 1/3,000 live births. Significant long-term concerns focus on bowel control and urinary and sexual functions.

Figure 336-1 Normal anorectal anatomy in relation to pelvic structures. A, Male. B, Female.

(From Peña A: Atlas of surgical management of anorectal malformations, New York, 1989, Springer-Verlag, p 3.)

Embryology

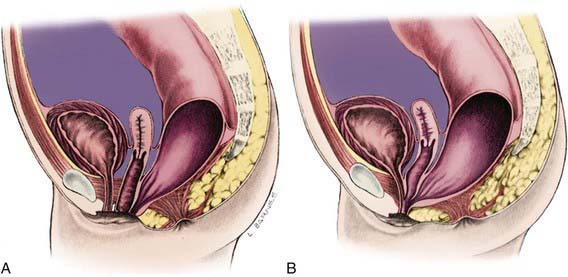

Imperforate anus can be divided into low lesions, where the rectum has descended through the sphincter complex, and high lesions, where it has not. Most patients with imperforate anus have a fistula. There is a spectrum of malformation in boys and girls. In boys, low lesions usually manifest with meconium staining somewhere on the perineum along the median raphe (Fig. 336-2A). Low lesions in girls also manifest as a spectrum from an anus that is only slightly anterior on the perineal body to a fourchette fistula that opens on the moist mucosa of the introitus distal to the hymen (Fig. 336-3A). A high imperforate anus in a boy has no apparent cutaneous opening or fistula, but it usually has a fistula to the urinary tract, either the urethra or the bladder (see Fig. 336-2B). Although there is occasionally a rectovaginal fistula, in girls, high lesions are usually cloacal anomalies in which the rectum, vagina, and urethra all empty into a common channel or cloacal stem of varying length (see Fig. 336-3B). The interesting category of boys with imperforate anus and no fistula occurs mainly in children with trisomy 21.

Associated Anomalies

There are many anomalies associated with anorectal malformations (Table 336-1). The most common are anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract in conjunction with abnormalities of the sacrum. This complex is often referred to as the caudal regression syndrome. Boys with a rectovesical fistula and patients with a persistent cloaca have a 90% risk of urologic defects. Other common associated anomalies are cardiac anomalies and esophageal atresia with or without tracheoesophageal fistula. These can cluster in any combination in a patient. When combined, they are often accompanied by abnormalities of the radial aspect of the upper extremity and are termed the VATERR (vertebral, anal, tracheal, esophageal, radial, renal) or VACTERL (vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheal, esophageal, renal, limb) anomalad.

Table 336-1 ASSOCIATED MALFORMATIONS

GENITOURINARY

VERTEBRAL

CARDIOVASCULAR

GASTROINTESTINAL

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Approach to the Patient

Evaluation includes identifying associated anomalies (see Table 336-1). Careful inspection of the perineum is important to determine the presence or absence of a fistula. If the fistula can be seen there, it is a low lesion. The invertogram or upside-down x-ray is of little value, but a prone cross-table lateral plain x-ray at 24 hr of life (to allow time for bowel distention from swallowed air) with a radioopaque marker on the perineum can demonstrate a low lesion by showing the renal gas bubble <1 cm from the perineal skin. A plain x-ray of the entire sacrum, including both iliac wings, is important to identify sacral anomalies and the adequacy of the sacrum. An abdominal-pelvic ultrasound and voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) must be performed. The clinician should also pass a nasogastric tube to identify esophageal atresia and should obtain an echocardiogram. In boys with a high lesion, the VCUG often identifies the rectourinary fistula. In girls with a high lesion, more invasive evaluation, including vaginogram and endoscopy, is often necessary for careful detailing of the cloacal anomaly.

Outcome

The ability to achieve rectal continence depends on both motor and sensory elements. There must be adequate muscle in the sphincter complex and proper positioning of the rectum within the complex. There must also be intact innervation of the complex and of sensory elements as well as the presence of these sensory elements in the anorectum. Patients with low lesions are more likely to achieve true continence. They are also, however, more prone to constipation, which leads to overflow incontinence. It is very important that all these patients are followed closely, and that the constipation and anal dilatation are well managed until toilet training is successful. Tables 336-2 and 336-3 outline the results of continence and constipation in relation to the malformation encountered.

Table 336-2 RESULTS OF SURGICAL TREATMENT OF ANORECTAL MALFORMATIONS: TOTAL CONTINENCE*

| TYPE | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|

| LOW | |

| Perineal fistula | 90 |

| Rectal atresia/stenosis | 75 |

| Vestibular fistula | 71 |

| HIGH | |

| Imperforate with no fistula | 60 |

| Bulbar urethral fistula | 50 |

| Short cloaca | 50 |

| Prostatic fistula | 31 |

| Long cloaca | 29 |

| Bladder neck fistula | 12 |

* Voluntary bowel movements, no soiling.

Modified from Levitt MA, Peña A: Outcomes from the correction of anorectal malformations, Curr Opin Pediatr 17:394–401, 2005.

Table 336-3 CONSTIPATION AND TYPE OF ANOGENITAL MALFORMATION

| TYPE | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|

| Vestibular fistula | 61 |

| Bulbar urethral fistula | 64 |

| Rectal atresia/stenosis | 50 |

| Imperforate with no fistula | 55 |

| Perineal fistula | 57 |

| Long cloaca | 35 |

| Prostatic fistula | 45 |

| Short cloaca | 40 |

| Bladder neck fistula | 16 |

Modified from Levitt MA, Peña A: Outcomes from the correction of anorectal malformations, Curr Opin Pediatr 17:394–401, 2005.

Georgeson KE, Inge TH, Albanese CT. Laparoscopically assisted anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus—a new technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:927-930.

Hsieh MH, Perry V, Gupta N, et al. The effects of detethering on the urodynamics profile in children with a tethered cord. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:391-395.

Levitt MA, Haber HP, Seitz G, et al. Transperineal sonography for determination of the type of imperforate anus. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:1525-1529.

Levitt MA, Patel M, Rodriguez G, et al. The tethered spinal cord in patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:462-468.

Levitt MA, Peña A. Outcomes from the correction of anorectal malformations. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17:394-401.

Levitt MA, Soffer SZ, Peña A. Continent appendicostomy in the bowel management of fecally incontinent children. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1630-1633.

Mattix KD, Novotny NM, Shelley AA, et al. Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE) for fecal incontinence in imperforate anus improves quality of life. Pediatr Surg Intl. 2007;23:1175-1177.

Peña A. Anorrectal malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1995;4:35-47.

Peña A, Guardino K, Tovilla JM, et al. Bowel management for fecal incontinence in patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:133-137.

Peña A, Hong AR. Advances in the management of anorectal malformations. Am J Surg. 2000;180:370-376.

Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Imperforate anus: long- and short-term outcome. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:79-89.

Rosen R, Buonomo C, Andrade R, et al. Incidence of spinal cord lesions in patients with intractable constipation. J Pediatr. 2004;145:409-411.

Sigalet DL, Laberge JM, Adolph VR, et al. The anterior sagittal approach for high imperforate anus: a simplification of the Mollard approach. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:625-629.

Torres R, Levitt MA, Tovilla JM, et al. Anorectal malformations and Down’s syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:194-197.

Tsakayannis DE, Shamberger RC. Association of imperforate anus with occult spinal dysraphism. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1010-1012.

Vick LR, Gosche JR, Boulanger SC, et al. Primary laparoscopic repair of high imperforate anus in neonatal males. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1877-1881.

336.2 Anal Fissure

Madoff RD, Fleshman JW. AGA technical review on the diagnosis and care of patients with anal fissure. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:235-245.

Nelson RL. Treatment of anal fissure. BMJ. 2003;327:354-355.

Sonmez K, Demirogullari B, Ekingen G, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled treatment of anal fissures by lidocaine, EMLA and GTN in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1313-1316.

336.3 Perianal Abscess and Fistula

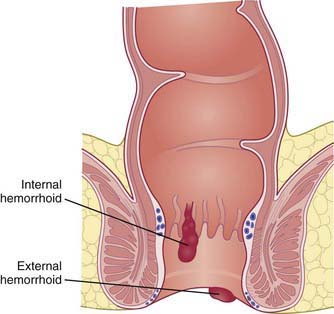

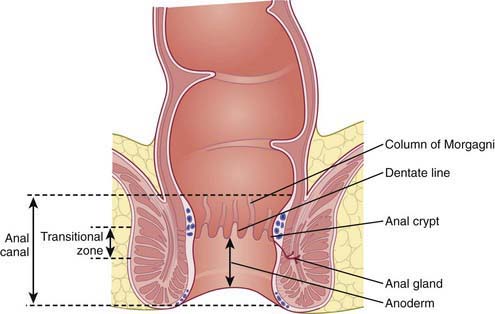

Children account for 0.5-4.3% of all patients presenting with perianal abscesses. These usually manifest in the first year of life and are of unknown etiology. Links to congenitally abnormal crypts of Morgagni have been proposed, suggesting that deeper crypts (3-10 mm rather than the normal 1-2 mm) lead to trapped debris and cryptitis (Fig. 336-4). The most common organisms isolated from perianal abscesses are mixed aerobic (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus) and anaerobic (Bacteroides spp., Clostridium, Veillonella) flora. Ten to 15% yield pure growth of E. coli, S. aureus, or Bacteroides fragilis. There is a strong male predominance in those affected younger than 2 yr of age. This imbalance corrects in older patients, where the etiology shifts to associated conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, leukemia, or immunocompromised states.

Figure 336-4 Anatomy of the anal canal.

(Adapted from Brunicardi FC, Anderson DK, Billar TR, et al: Schwartz’s principles of surgery, ed 8, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill.)

336.4 Hemorrhoids

Clinical Manifestations

Presentation depends on the location of the hemorrhoids. External hemorrhoids occur below the dentate line (Figs. 336-4 and 336-5) and are associated with extreme pain and itching, often due to acute thrombosis. Internal hemorrhoids are located above the dentate line and manifest primarily with bleeding, prolapse, and occasional incarceration.

336.5 Rectal Mucosal Prolapse

Clinical Manifestations

Rectal mucosal prolapse usually occurs during defecation, especially during toilet training. Reduction of the prolapse may be spontaneous or accomplished manually by the patient or parent. In severe cases, the prolapsed mucosa becomes congested and edematous, making it more difficult to reduce. Rectal prolapse is usually painless or produces mild discomfort. If the rectum remains prolapsed after defecation, it can be traumatized by friction with undergarments, with resultant bleeding, wetness, and potentially, ulceration. The appearance of the prolapse varies from bright red to dark red and resembles a beehive. It can be as long as 10-12 cm. See Chapter 337 for a distinction from a prolapsed polyp.