Chapter 6 Surgical Approaches to the Elbow

General principles

The application to the elbow of general surgical principles is probably more important than when these principles are applied to any other anatomical site.1,2 The following should be carefully considered when elbow surgery is undertaken:

Clinical Pearl 6.1

Anticipate common patterns of injury when preparing and deciding on the surgical approach.

Exposure is an important part of the procedure but reconstruction and repair are as critical.

Use full-thickness flaps when exposing the elbow.

Always maintain anatomical orientation during the procedure to decrease neurovascular complications.

Lateral approaches

Several intermuscular intervals have been described. Kocher’s approach utilizes the interval between the anconeus and the extensor carpi ulnaris and can be extended proximally and distally.3 Kaplan described an approach in the interval between the extensor digitorum communis and the extensor carpi radialis brevis and longus.4

Kocher approach

Technique

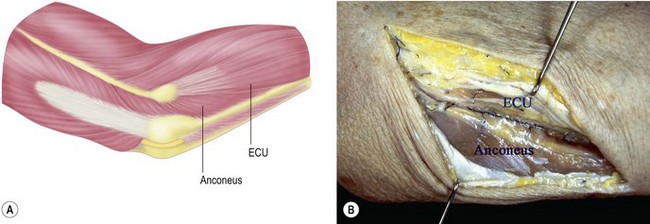

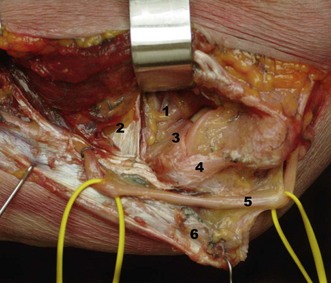

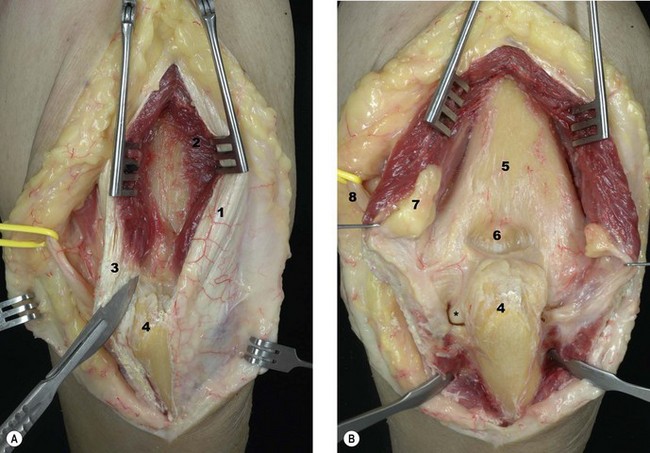

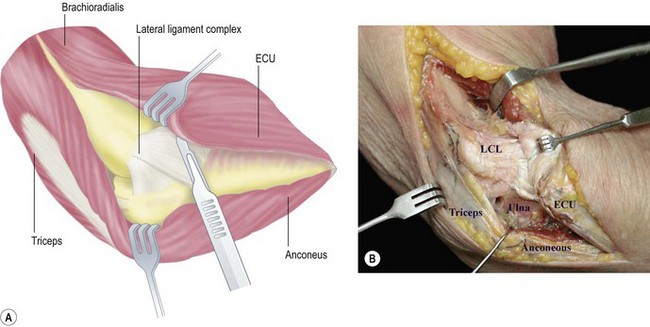

Either a posterior skin incision with dissection of a full-thickness lateral fasciocutaneous flap or a limited distal lateral skin incision may be used. The anconeus and extensor carpi ulnaris muscles are identified by palpation. A thin strip of fat can almost always be observed in the interval between these muscles (Fig. 6.1). The muscle fibres of the anconeus and the extensor carpi ulnaris muscles tend to blend together towards the insertion, so it is easier to develop the interval in its distal part and then progress proximally. The deep fascia is then opened and the interval is developed by dissecting the anconeus posteriorly. The lateral elbow capsule with the annular ligament is identified and incised longitudinally anterior to the lateral ulnar collateral ligament.

Modifications

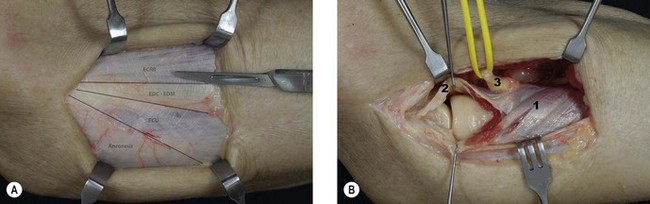

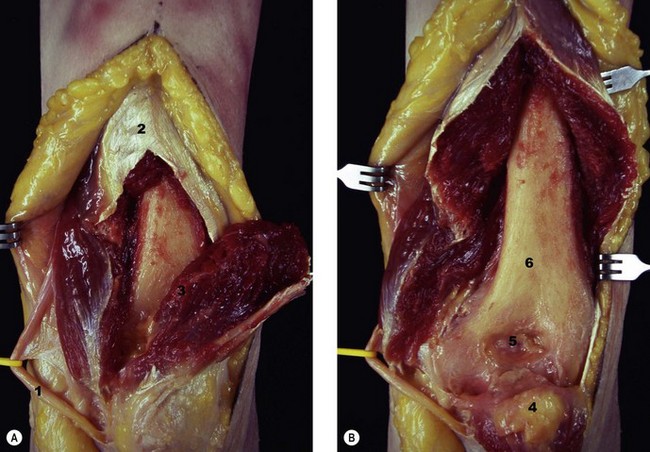

For reconstruction of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament, this approach can be extended proximally above the lateral epicondyle by developing the interval between the triceps and the brachioradialis (Fig. 6.2A). Once this is done, the rest of the extensor mass can be sharply incised from the epicondyle, respecting the insertion of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament. In order to achieve adequate exposure of the crista supinatoris, the anconeus along with the lateral aspect of the triceps tendon are reflected posteriorly (Fig. 6.2B).5

Reproduced with permission of Sales JM, Llusá M, Forcada P, et al. Orozco. Atlas de osteosíntesis. 2nd edn. Fracturas de los huesos largos. Vías de acceso quirúrgico. Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2009.24

Mansat and Morrey described the use of a limited proximal lateral approach for capsular release for stiff elbows, which they termed the ‘column procedure’.6 This exposure may be a proximal extension of the Kocher approach or a focused isolated proximal approach. The exposure is based on a dissection made anteriorly to the lateral border of the distal humerus, elevating the distal aspect of the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus from the humerus and entering the interval between the brachialis and the capsule. Access to the posterior capsule involves elevation of the triceps to form the posterior part of the humerus.

Kaplan approach

Technique

A skin incision is made on the lateral aspect of the elbow from the epicondyle extending distally 4 cm towards the ulnar styloid process. The interval between the extensor digitorum communis and the extensor carpi radialis brevis and longus is developed exposing the underlying capsule which is incised longitudinally to gain access to the radial head (Fig. 6.3).

The radial nerve is at particular risk during this approach but this can be reduced by pronation of the forearm, which moves the nerve away from the operative field.7

Kocher posterolateral extensile triceps sparing approach

Technique

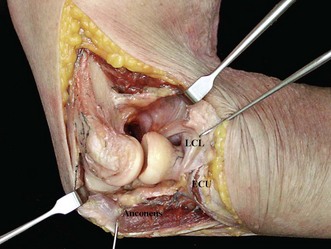

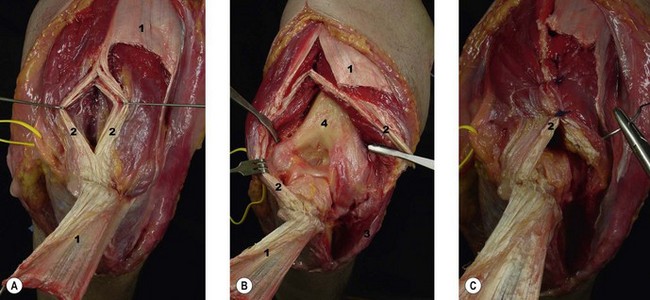

This exposure is an extension of the limited exposures described earlier and involves the release of the collateral ligaments and capsule. A midline posterior skin incision is used. The triceps is elevated from the posterior aspect of the humerus, and dissected anteriorly from the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus. The Kocher interval is identified and developed to expose the joint capsule. The anconeus is elevated from the ulna and the triceps attachment to the lateral epicondyle is also reflected posteriorly, leaving its insertion to the olecranon intact. The lateral collateral ligament is then released from the humeral origin, allowing dislocation of the elbow joint by applying a varus stress (Fig. 6.4).

Modifications

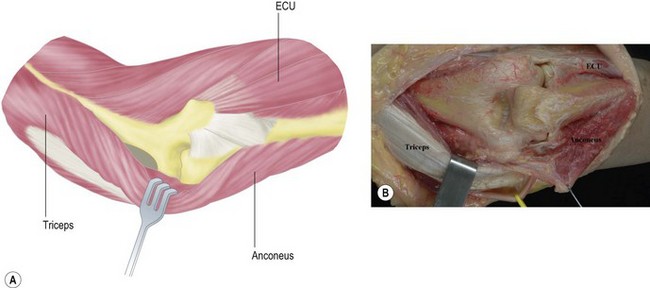

This approach was modified in the Mayo Clinic to include complete release of the triceps from the olecranon, reflecting the triceps mechanism and anconeus from lateral to medial. The triceps and anconeus sleeve is reflected from the tip of the olecranon by releasing Sharpey’s fibres (Fig. 6.5).2

Medial approach

Medial approaches to the elbow are less frequently used than lateral approaches to the joint. They may be indicated to address pathology of the ulnar nerve, injuries of the medial collateral ligament, fractures of the coronoid process and contracture release. Recently, less invasive approaches through the pronator teres have been described for medial joint surgery, including medial ligament reconstruction and other procedures that affect medial structures.8

Extensile medial approach (Hotchkiss)9

Technique

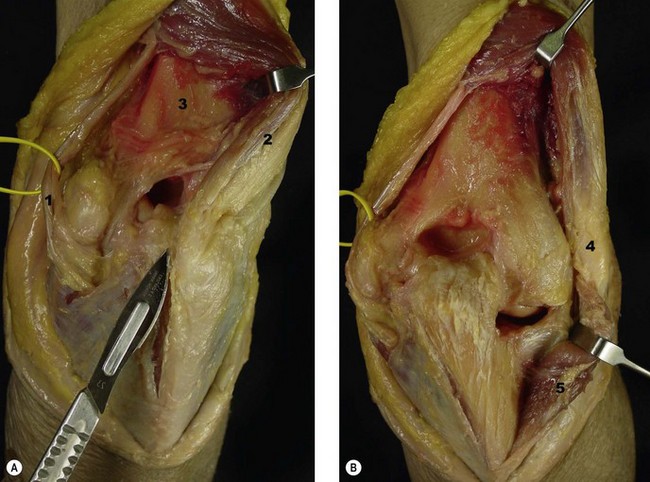

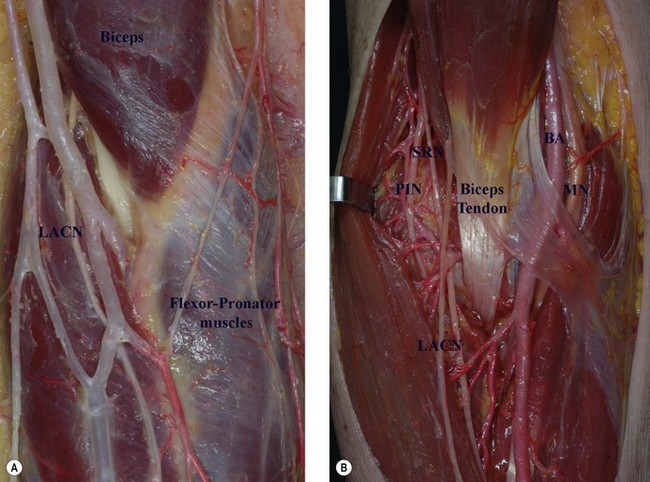

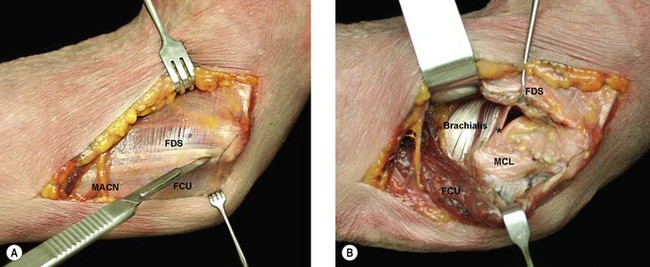

The subcutaneous dissection must be performed cautiously to avoid injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. This nerve can be localized running on top of the superficial fascia (Fig. 6.6A). The ulnar nerve should be identified proximally and mobilized. The medial intermuscular septum should then be released for a distance of about 5 cm. An incision is made on the supracondylar ridge 5 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and continued distally towards the pronator and a portion of the common flexor tendon. A portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon is left attached to the epicondyle posteriorly as this facilitates closure at the end of the procedure. A Cobb elevator is helpful in elevating the anterior structures from the distal humerus until a wide retractor can be introduced (Fig. 6.6B).

Reproduced with permission of Sales JM, Llusá M, Forcada P, et al. Orozco. Atlas de osteosíntesis. 2nd edn. Fracturas de los huesos largos. Vías de acceso quirúrgico. Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2009.24

As the dissection proceeds laterally and distally, the brachialis muscle is elevated from the capsule. Another option is to start the dissection distal to the coronoid process, which can be palpated, and proceed proximally. The flexor tendon can then be incised with the knife blade placed almost parallel to the plane of dissection and around the sublime tubercle. This manoeuvre allows the plane to be found between the medial collateral ligament and the flexor muscle mass, while protecting the former. The dissection can then be continued proximally until it links up with the previously performed proximal dissection (Fig. 6.7).

Posterior approaches

Skin incision

A 15 cm straight skin incision passing either medial or lateral to the tip of the olecranon is advised, although an ‘S’ incision has also been described. Some surgeons prefer to go laterally to prevent any tenderness of the scar when resting the elbow, and to avoid the risk of damaging the ulnar nerve. Other surgeons have attributed better healing to a medial rather than lateral incision.2

In either case, full-thickness fasciocutaneous flaps are elevated laterally and medially, preserving the subcutaneous arterial plexus and the cutaneous nerves (Fig. 6.8).

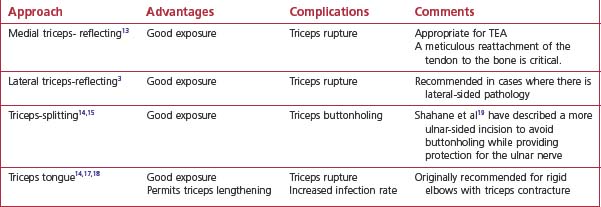

Triceps

Management of the triceps tendon depends on the pathology to be addressed. Several options are available, including approaches in which the triceps attachment is preserved (Alonso-Llames, Morrey and Adams, Patterson),10–12 where it is reflected from medial to lateral (Bryan and Morrey),13 reflected from lateral to medial (Kocher posterolateral extensile approach), split in the midline (Campbell, Gschwend, Van Gorder)14–16 or divided using a triceps tongue (Campbell, Van Gorder, Wadsworth)14,17,18 (Table 6.1).

Triceps preserving: Alonso-Llames10

Technique

A posterior skin incision is made medial or lateral to the tip of the olecranon. Full-thickness fasciocutaneous flaps are elevated. The medial and lateral borders of the triceps are incised and elevated from the posterior aspect of the distal humerus. The ulnar nerve must be identified and protected. The distal humerus can be buttonholed medially or laterally to gain access to the proximal forearm (Fig. 6.9).

Modifications

Morrey described a variation of this technique primarily for distal humeral non-unions treated with elbow replacement. On the lateral side, the extensor origin and the lateral collateral ligament complex are released from the lateral epicondyle. Medially, the common flexor muscle and tendon mass are elevated along with the medial collateral ligament. After resection, the forearm can be rotated to facilitate exposure of the proximal ulna.2

Patterson et al12 also described a modification of this approach in order to increase distal exposure. Laterally, the interval between the extensor carpi ulnaris and the anconeus is developed and continued distally with subperiosteal dissection of the extensor carpi ulnaris. On the medial side, the flexor carpi ulnaris is elevated subperiosteally.

Posterior triceps splitting: Campbell14

Technique

The triceps tendon and muscle are longitudinally incised, exposing the distal humerus proximally and proceeding distally by reflecting the anconeus laterally and the flexor carpi ulnaris medially (Fig. 6.10). Subperiosteal dissection should be done at the level of the olecranon attachment. The ulnar nerve may be visualized medially and protected. Closure of the aponeurosis is done with side-to-side sutures. Transosseous sutures at the triceps insertion may be added to augment the repair.

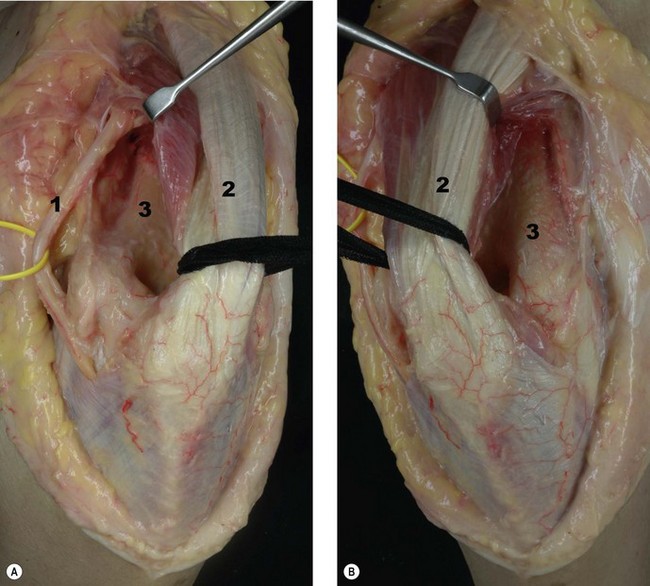

Triceps splitting–tendon reflection: V-Y approach

This approach was described by Campbell, and later modified by van Gorder and Wadsworth, for treating elbow contractures with a scarred and shortened triceps.14,16–18

Technique

In the original approach, the deep head of the triceps is divided in its midline for a length of about 8 cm. The flap is distally based and should extend to the outer part of the humeral condyles in order to allow an adequate approach (Fig. 6.11). Sufficient tendon tissue at both sides of the flap must be preserved to obtain a good repair. To perform a V-Y advancement the triceps is sutured in the midline for the required length. The rest of the flap is then repaired at its new length to the outer edges of the aponeurosis with interrupted sutures.

Reproduced with permission of Sales JM, Llusá M, Forcada P, et al. Orozco. Atlas de osteosíntesis. 2nd edn. Fracturas de los huesos largos. Vías de acceso quirúrgico. Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2009.24

We think this approach has an unacceptable rate of infection and triceps disruption. We avoid complete triceps disruption by elevating a flap with the superficial triceps aponeurosis and then entering the true triceps tendon longitudinally, through an avascular area (Fig. 6.12). This approach preserves the vascularity of the distal flap and allows a much better repair.

Modifications

Van Gorder16 described a modification of this technique in which the incision on the medial head of the triceps runs obliquely in order to avoid cutting off the triceps proximally. The incision runs from anterior distal to posterior proximal, leaving the entire thickness of the muscle attached to the base of the flap.

Wadsworth18 described a modification to enhance the exposure. After creating the flap, the incision is extended distally between the anconeus and the extensor carpi ulnaris, reflecting the anconeus medially and allowing access to the lateral aspect of the joint.

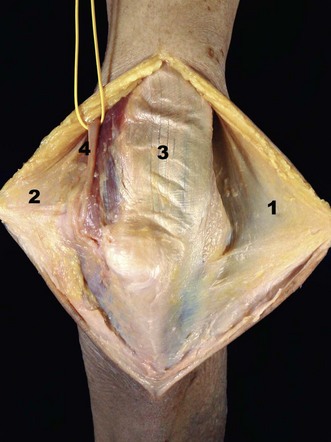

Posteromedial extensile: Bryan–Morrey approach13

Technique

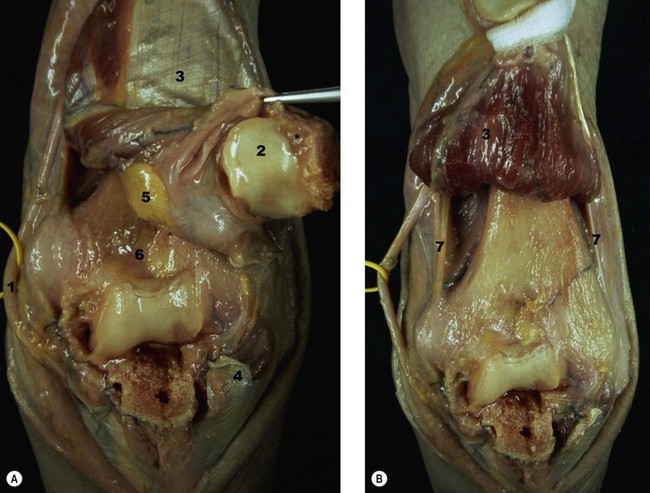

The triceps is released from the entire posterior aspect of the distal humerus. The forearm fascia and ulnar periosteum are elevated from the medial margin of the ulna. The triceps tendon is carefully detached from the tip of the olecranon by sharp dissection of Sharpey’s fibres. The lateral margin of the proximal ulna is then identified and the anconeus is elevated from its ulnar bed. Finally, the extensor mechanism is reflected laterally from the margin of the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 6.13).

Modifications

Wolfe and Ranawat19 reported a modification of this approach in which the ulnar nerve is exposed but not transposed and the triceps is released by osteotomizing its attachment on the olecranon through a thin wafer of bone, in an effort to achieve reliable healing.

Shahane and Stanley20 have also described a modification of this approach with the aim of reducing the incidence of ulnar neuropathy. After decompression of the ulnar nerve the triceps is split, with one-third medial and two-thirds lateral. The medial third is reflected medially with the ulnar nerve and the lateral two-thirds are reflected laterally, allowing excellent exposure of the distal humerus.

Olecranon osteotomy

The chevron osteotomy is the preferred method of osteotomizing the olecranon, in detriment to oblique or transverse osteotomies.21,22

Technique

A posterior midline skin incision is used. The ulnar nerve must be located and protected throughout the procedure. A 3.2 mm drill hole can be made that crosses the osteotomy site to introduce a lag screw at the completion of the procedure. The joint is exposed at the greater sigmoid notch and a sponge may be placed in the joint to protect the articular surface. The osteotomy is made with a distal chevron and should be started with a saw and finished with an osteotome. This allows the formation of cracks that may facilitate repositioning of the bony fragment. The fragment and the tendon are retracted proximally (Fig. 6.14). Capsular attachments and the posterior component of the collateral ligaments may need to be divided to gain more access to the joint. At the completion of the procedure the osteotomized fragment is reduced and fixed with a cancellous lag screw, a cerclage with K-wires or a plate.

Anterior approach

Except for biceps tendon reconstruction, anterior approaches to the elbow are rarely used owing to the vicinity of important neurovascular structures. The anterior approach is based on the one described by Henry.23

Extensile anterior exposure of the elbow

Indications

The proximity of important neurovascular structures is the main disadvantage of this approach. These include the proximity of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve in the superficial plane and the median nerve and brachial artery in the deep plane of dissection. The brachialis muscle is between the joint and the median nerve, and the radial nerve is in the interval between the brachialis and the brachioradialis muscle. These anatomical features must be kept in mind at all times to avoid inadvertent injury (Fig. 6.15).

1 Harty M, Joyce JJIII. Surgical approaches to the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:1598-1606.

2 Morrey BF. Surgical exposures. In: Morrey BF, editor. The elbow and its disorders. 3rd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000:109-135.

3 Kocher T. Text-book of operative surgery, 3rd edn. London: Adam & Charles Black; 1911. p. 313–8

4 Kaplan EB. Surgical approaches to the proximal end of the radius and its use in fractures of the head and neck of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg. 1941;23:86.

5 Nestor BJ, O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF. Ligamentous reconstruction for posterolateral rotator instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:1235-1241.

6 Mansat P, Morrey BF. The column procedure: a limited lateral approach for extrinsic contracture of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1603-1615.

7 Strachan JH, Ellis BW. Vulnerability of the posterior interosseous nerve during radial head resection. J Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53B:320-323.

8 Dines JS, ElAttrache NS, Conway JE, et al. Clinical outcomes of the DANE TJ technique to treat ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(12):2039-2044.

9 Kasparyan NG, Hotchkiss RN. Dynamic skeletal fixation in the upper extremity. Hand Clin. 1997;13:643-663.

10 Alonso-Llames M. Bilaterotricipital approach to the elbow. Acta Orthop Scand. 1972;43:479-490.

11 Morrey BF, Adams RA. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humerus nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:67-72.

12 Patterson SD, Bain GI, Mehta JA. Surgical approaches to the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;370:19-33.

13 Bryan RS, Morrey BF. Extensive posterior exposure of the elbow: a triceps sparing approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;166:188-192.

14 Campbell WC. Incision for exposure of the elbow joint. Am J Surg. 1932;15:65-67.

15 Gschwend N. Our operative approach to the elbow joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1981;98:143-146.

16 Van Gorder GW. Surgical approach in old posterior dislocation of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1932;14:127-143.

17 Van Gorder GW. Surgical approach in supracondylar ‘T’ fractures of the humerus requiring open reduction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1940;22:278-292.

18 Wadsworth TG. A modified posterolateral approach to the elbow and proximal radioulnar joints. Clin Orthop. 1979;144:151-153.

19 Wolfe SW, Ranawat CS. The osteo-anconeus flap: an approach for total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:684-688.

20 Shahane SA, Stanley D. A posterior approach to the elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;81:1020-1022.

21 MacAusland WR. Ankylosis of the elbow, with report of four cases treated by arthroplasty. JAMA. 1915;64:312-318.

22 Llusá M, Ballesteros JR, Forcada P, et al. Atlas de disección anatomoquirúrgica del codo. Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2009.

23 Henry AK. Extensile exposure, 2nd edn. E & S Livingstone: Edinburgh; 1966. p. 113–15

24 Sales JM, Llusá M, Forcada P, et al. Orozco. Atlas de osteosíntesis. Fracturas de los huesos largos. Vías de acceso quirúrgico. 2nd edn. Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2009.